4.5 The 2011 Census

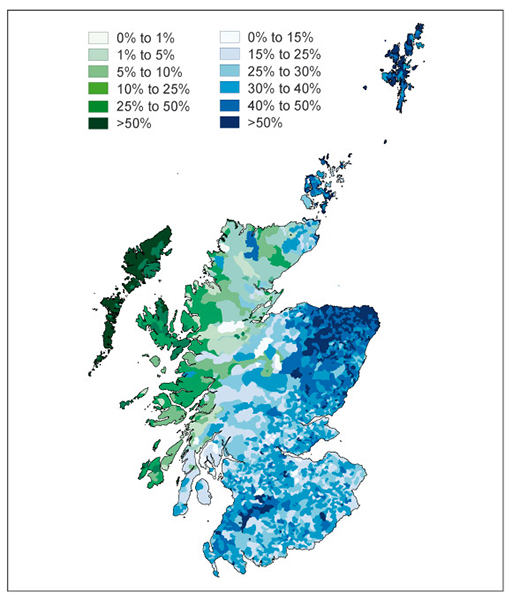

In March 2011 the census of Scotland asked for the first time in its history whether people could speak, read, write or understand Scots. At the time, the population of Scotland was 5,295,403.

The figures for the most Scots speaking regions according to the answers given by people who filled in the survey may be broken down into the ‘biggest single figures’, and the ‘biggest percentages’ as part of the regional council population.

| Biggest single figures | Biggest percentages of regional council population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Glasgow City Council Region: | 142,111 | Aberdeenshire Council Region: | 49% |

| Fife Council Region: | 123,205 | Shetland Council Region: | 49% |

| Aberdeenshire Council Region: | 119,078 | Moray Council Region: | 45% |

Whilst 49% of Shetland residents responded to the 2011 Census confirming they spoke Scots, the population of Shetland at the time of the census was only 22,400.

The Biggest Single Figures recorded for Glasgow and Fife greatly exceed the Single Figures and the populations of places such as Shetland and Orkney.

Glasgow and Fife are both part of the dialect region commonly referred to as Central Scots.

(Scotland's Census,Census Results [Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. (Hide tip)] , 2011)

As discussed in the previous section 4.3, Insular Scots can be divided into Shetlandic and Orcadian, and both have been studied in depth by the likes of Jakob Jakobsen and Hugh Marwick – both men publishing respected works on the linguistic features found within the Northern Isles of Scotland.

As you learned in section 4.2, the dialect of Central Scots can be broken down further as West Central, South Central, East Central South and East Central North as each area has a few linguistic features unique to their region.

In Scots language circles it was a proud moment for places such as Orkney, Shetland and Moray to be recognised as having every second resident recognised as a Scots speaker, and in a similar way as Glaswegian and West Central Scots have.

“… enormous internal prestige. The strength of the dialect there lies with the strength of the working-class identity which is basic to people from the Western industrial belt. In addition, by means of the media working-class heroes such as footballers or comedians have given Glaswegian ‘underground’ prestige in the rest of Scotland, so that its influence is extending well beyond Glasgow”.

What becomes clear across all of Scotland are the passion and feelings of pride that exist across the country for the Scots language. But, due to social and cultural factors that had an impact throughout centuries, there is still a need to identify, understand and respect the dialect diversity which exists.

An individual wishing to learn Scots language would, rather than learning a standard language, encounter dialect diversity across the country, with linguistic features relating to vocabulary and grammar changing within the areas of Scotland identified above.

Whilst recognition of this element of Scots language is essential to properly grasp the sense of identity Scots speakers from different parts of Scotland have, the over-emphasis placed by Scots speakers on the diversity aspect of the language is one of the reasons for the division that keeps Scots language from truly uniting as a language with a community of 1.5 million speakers, and may hinder the chances of the figure rising in the future.

The reason for this over-emphasis could be due to the different history of the dialects spoken in Shetland, Orkney and Caithness within Insular Scots, in comparison to the history of the Glasgow or Fife dialects within Central Scots.

Or, it could be the more recently formed social perceptions of “rural” and “broad” Scots spoken in Aberdeenshire or the Borders versus the streets of Dundee or Leith.

Either way, the content of this Dialect diversity unit is important for achieving an accurate understanding of what the language is today, and where it has been in the past across Scotland.

Activity 10

In this section you have elaborated further upon the points discussed in the previous sections on Shetland – this time with reference to Glaswegian, the Central Scots dialects of Lowland Scotland and the 2011 Census.

- a.After reading the text in this section, note points which are of interest to you for reflection at the end, such as:

- 2011 was the first time a question on Scots had been included in the Census

- Glasgow and Fife are both part of the dialect group Central Scots

- b.At the end of this activity compare your notes with what you wrote in Activity 1.

4.4 Dialect diversity and bilingualism