Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 21 February 2026, 11:27 AM

Session 8 Changing practice

Introduction

This course provides opportunities to think about making changes to your work practice to plan and deliver education online. Session 8 introduces ways to start planning to do this. Being aware of debates about how people use digital technology and the effects it has on them will help you to think about ways of combining technology and pedagogy effectively.

Practitioner reflections

This session begins with a video from Sarah, who talks about changes she made in her teaching and the implications of these for her and for her learners. As you watch the video or read the transcript make a note of the changes that Sarah made when she moved online and decide which you might consider using or encouraging others to try.

Transcript

How have you made a change in your teaching?

Learning outcomes

By the end of this session, you should be able to:

- identify the benefits that an internet connection can offer learners;

- understand the difference between ‘digital residents’ and ‘digital visitors’;

- incorporate support for student study skills within your practice;

- explain why learning design is used when developing and reviewing courses.

1 Making the change

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many institutions to move their teaching online with little or no notice. There was little time for planning, for training, or for preparation. Staff and learners around the world found the situation very challenging and struggled to cope with the rapidly changing situation.

As you have seen in this course, online teaching requires approaches that are different to those used in the classroom. Simply moving lectures online may be the fastest way to move to distance learning in an emergency, but in the long term it does not make the best use of online learning and it puts students in the role of passive consumers of content rather than active learners.

1.1 Technology supporting learning

Whether you are making the move to online teaching for the first time, shifting to a blended approach (combining online and face-to-face teaching), or developing your current approach, you will find it useful to reflect on the benefits that an internet connection can offer learners (Ferguson, 2019). These benefits go beyond the ability to participate in lectures or seminars when it is not possible to be on campus. They include connectivity, extension, inquiry, personalisation, publication and scale.

Connectivity: The internet has opened up many new ways of working with other people around the world. It offers a wide range of tools that can support networked, collaborative and conversational approaches to learning. These include the tools you looked at in Session 4 and the OER you considered in Session 6. Learners can link with others across the country and around the world.

Extension: Technology supports extended learning, connecting learning experiences across locations, times, devices and social settings. It offers new tools for creative exploration of the world and provides increasing opportunities to connect learning outside the classroom with learning inside the classroom.

Inquiry: Learners who have access to a smartphone also have access to an array of built-in sensors that enable them to measure, interrogate, analyse and record their environment. Technology provides them with new means and structures for organising data, new reference sources, and new tools that can be used to investigate this information space. The internet supports citizen inquiry, enabling learners to engage in scientific investigations that involve the collection and analysis of data on a worldwide scale.

Personalisation: Interactions with technology generate data sets that reveal patterns and trends. These data sets can be used to enhance an individual’s learning experience through offering learning paths or resources that are personalised to meet individual needs and learning preferences. They can also be used to enable learners to understand and develop their aptitudes and skills.

Publication: Learners are no longer restricted to a limited local audience. They can use digital tools and the internet to engage in authentic tasks that connect their learning with experiences beyond the university. They can also share their work with a worldwide audience by publishing their creations or their findings.

Scale: Education can now be delivered at scale through Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). When these scaled-up courses make use of social networking and learning through conversations, interactions become richer as learners around the world share ideas and perspectives. MOOCs, or parts of MOOCs, can be incorporated within the curriculum to enrich it or offered to learners as extension activities.

When preparing for change bear in mind that many students will not have a good internet connection at all times. This means planning for asynchronous interaction, so that activities can be carried out when individuals are online, rather than requiring everyone to be online at the same time. When students do need to be online together consider whether they could do this in groups, at a time of their choosing, rather than asking everyone to be online at the same time.

2 Technology or pedagogy?

Despite the advantages of online learning identified in the previous section, there is often a tension between technology and pedagogy in online teaching. Some people view the technology simply as a delivery system and focus on the pedagogy. Others prefer to make use of the possibilities offered by technology and wait for the theory to catch up.

It is probably more useful to think of the two as being involved in a dialogue. Technology opens up new possibilities and it can be used in ways that its designers never intended. This drives new ways of approaching teaching and learning which feed back into technology development, and the cycle continues. This view of technology, and particularly how it relates to education, is addressed by Weller (2011) in Chapter 1 of The Digital Scholar.

This tension between the roles of technology and pedagogy is apparent throughout the educational system, but it is particularly acute when it comes to online education. Many of the topics covered by this course would not be possible without internet technology. However, it is also important to consider the roles of learners and educators and what they bring to each online education context.

2.1 Visitors and residents

The different ways in which people interact with and understand digital technology are the subject of ongoing research and debate. For example, Prensky (2001) made a distinction between ‘digital natives’ and ‘digital immigrants’. He argued that younger generations (the ‘digital natives’) are immersed in technology when entering education and they have a different understanding of and relationship with it than the older ‘digital immigrants’ who have to learn to use it. This idea attracted much media attention, however, the claims about digital immigrants did not stand up to scrutiny. For example, Bennett et al. (2008) found as much difference within the technology use of the younger generations who were labelled ‘digital natives’ as there was between them and the older generations described as ‘digital immigrants’. Importantly, the technology skills of younger users were often limited. They were familiar with some tools and applications but knew little or nothing about others. It is a mistake to assume that someone is confident or proficient in using technology simply because they are younger.

David White rephrased this idea as ‘Digital Residents’ and ‘Digital Visitors’. This description covers a range of online behaviours, and the same person can operate in ‘resident’ or ‘visitor’ mode for different tasks. White and Le Cornu (2011) define the two groups in this way:

‘Visitors understand the Web as akin to an untidy garden tool shed. They have defined a goal or task and go into the shed to select an appropriate tool which they use to attain their goal. Task over, the tool is returned to the shed.

…

Residents, on the other hand, see the Web as a place, perhaps like a park or a building, in which there are clusters of friends and colleagues whom they can approach and with whom they can share information about their life and work. A proportion of their lives is actually lived out online.’

When making changes to your educational practice be aware of how much the technology is shaping your advances. Try to decide whether you are acting as a ‘resident’ or a ‘visitor’ and whether you expect learners to be one or the other.

You should also reflect on the assumptions you make about who will be capable of engaging with online learning. It is important to assess and – where necessary – develop your learners’ skills as well as your own in order to engage successfully with online education.

Activity 8.1: Visitors or residents?

David White explains the Visitors and Residents model in this video (transcript).

As you watch the video make notes on which elements you feel might apply to your learners – which activities do you think they would identify as ‘residents’ and which as ‘visitors’? Do you have a mix in your class or institution? If so, what is the balance between visitors and residents?

Comment

This activity is designed to help you to think about the technological skills and needs of your students. The models described might help you to categorise students with respect to different tasks or technologies. This, in turn, should help you identify how to meet their needs with online and blended teaching. For example, you may find that some students are always present and could be very comfortable with merging online learning activities into social media practices that are a part of their everyday lives. Others may go online to complete a specific task that is set for them but will not think they need to always be connected. Examine your expectations of their behaviours and be flexible in response to their approaches.

The video stresses it is important not to oversimplify assumptions about the need to teach digital skills to any audience. Instead, it is important to recognise that all learners and those involved in education may need to develop their skills in order to engage fully with online learning.

3 Learning to learn online

We learn from a very young age how to behave in an educational institution or classroom. As soon as they start school, pupils are taught where to go, what is allowed, where to focus their attention, when they can respond, when to take a break, and where resources are located. By the time students reach university, this knowledge about how to learn in a physical classroom is second nature and they rarely think of it as something they were taught.

At the same time the constraints of a physical classroom become so much a part of life that they are hardly noticed. As a result, when people around the world moved rapidly to online teaching during the pandemic they often reproduced these constraints. These include assumptions such as:

- Learning takes place at set times.

- Learning must be synchronous.

- The educator must see the learners.

- The learners must see the educator.

- Class members should all engage at the same time.

- Class members should all take a break at the same time.

- Learners should be suitably dressed.

- Learners should sit still.

- Technology is distracting.

Sometimes these constraints remain appropriate when teaching at a distance, but in many cases they can be set aside completely, adding flexibility to online learning.

Activity 8.2: Making assumptions

Consider the list of constraints above. For each constraint note whether you believe it should apply in online learning all the time, some of the time, or never.

In cases you label ‘some of the time’, note the conditions that would make that constraint necessary in an online setting.

If you identify other constraints that apply in a physical setting but not online, you could share them in the course community of practice Facebook group.

Comment

One reason that educators sometimes find online teaching limiting is that their planning takes into account the limitations of being online (such as the need for a good internet connection) and then adds the restrictions associated with a physical location (such as the requirement for everyone to study at the same time because that is when the classroom is available). By reflecting on your assumptions about how and where learning can take place you may identify restrictions that have been limiting you but that need not apply in an online setting.

3.1 Self-regulation

The skills needed by students when they learn online are not exactly the same as those they need in a physical classroom. As university students they have some experience of managing their own learning but they may still rely on the university and their lecturers to keep them on track. For example, they may expect their time to be organised for them or resources and study spaces to be supplied. When working at a distance, they need self-regulation skills to manage their own learning.

Self-regulation has three phases (Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009). The planning phase is concerned with preparation for learning. The performance phase covers the learning activities. This is followed by the self-reflection phase, in which students consider their progress and begin to plan for the future.

Planning phase: Support students to set goals that they value, plan how to achieve those goals, and think ahead to identify when resources and support will be available.

Performance phase: Provide students with different strategies for approaching tasks. They need to be able to manage their time, know how to monitor their learning and be aware of where they can go and who they can contact for help. Encourage them to think broadly about where they can access support when a tutor is not available. Classmates, other students, friends and family, social networks, libraries, resource centres and online groups may all be options depending on the type of help required.

Self-reflection phase: Offer a structure for reflecting on learning. Students need to be able to evaluate their progress, understand why things worked or did not work, and understand how they could improve their approach.

‘Double-loop learning’ is important in this process. Double-loop learners do not simply solve immediate problems; they also reflect on how they are solving those problems, think about what they are trying to achieve, question their assumptions, consider how to become more effective, and remember to try different options. This helps them to become self-determined learners with the ability to seek out sources of knowledge and make use of appropriate online networks for advice and support.

Activity 8.3 Student study skills

Students need a variety of study skills to be able to learn online. These are not confined to self-regulation, but also include setting up a study environment, getting organised, time management, computing skills and the ability to manage stress.

Begin by looking at the online resources provided by your university to support students to develop these skills. Note what is available and where the gaps are. If your university has good resources that are openly available, you could share a link to these in the course community of practice Facebook group.

Use the two websites below to locate resources that could help your students to develop the study skills they require.

Comment

In most cases, you will find that university advice about study skills relates to learning in a physical environment. The two websites linked above point to resources that could help you to fill the gaps. Many institutions have redesigned their study skills support in response to COVID-19, so you may find that some links do not work, but the majority remain active.

4 Learning design

Throughout this course, you have seen that designing an online experience for learners is not the same as other forms of teaching. Learning design provides a way of going about this systematically. Mor and Craft (2012) define learning design as ‘the act of devising new practices, plans of activity, resources and tools aimed at achieving particular educational aims in a given situation’ (p. 86).

Learning design is part of any educator’s practice. It involves preparing for teaching/training sessions as well as creating learning materials, activities and assessments. Learning design is so core to what educators do, that it is often taken for granted. It is assumed that it ‘just happens’. In other words, design is so embedded in educators’ practice that it tends to be implicit. It is rarely articulated formally or externalised for others, apart from at a relatively superficial level in the module syllabus or lesson plan.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in trying to understand educators’ design processes better and make them more explicit. There are a number of reasons for this, but three are particularly worth noting.

- Reviewing and adjusting: In order to ensure the quality and robustness of educational innovations, they need to be reviewed from various perspectives – technological, pedagogical and others. The sooner the innovations are reviewed, the easier it is to make any necessary adjustments. Sharing and discussing innovations at the design phase can avoid costly mistakes at later stages of production.

- Sharing the development process: By making the design process explicit, it can be easily shared with others, which means good practice can be transferred.

- Providing guidance: The variety and complexity of resources and technologies available means that teachers and other education practitioners need clear guidance to help them find relevant tools and resources, as well as support in incorporating these into the learning activities they are creating.

Note that the term ‘learning design’ is still being defined and negotiated. It overlaps to some extent with other terms, such as ‘instructional design’, ‘curriculum design’ and ‘module design’. Mor and Craft's definition represents one possible interpretation, and their paper discusses alternative definitions proposed by others.

Activity 8.4 Learning design

Visit The Open University’s Learning Design Resources. Browse the guides, posters and tools available on the site, and look in more detail at ones that interest you.

Make notes about resources you could use in your own work and how you think you might do this. For example, you could encourage others to use a certain resource, plan a workshop activity or use the resources as a guide to your own design work.

Comment

Many good ideas and best practice resources are available online for educators to use. This activity helps you to start thinking about the kinds of resources you might look for and how these could be altered to fit teaching needs at your institution.

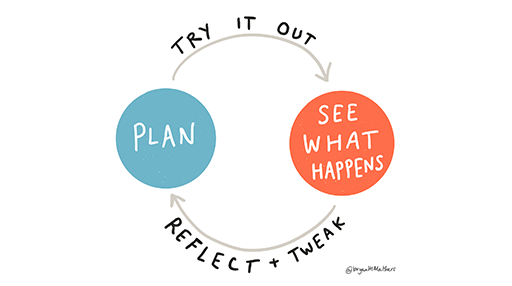

5 Changing practice

The following guidance may help you as you plan to make changes that can make full use of the advantages of online learning.

- Start small and start now. Over time you may start to overthink your planned change; your objectives may be forgotten as you deal with intervening issues or you may start to vacillate between various potential changes. Pick something small that you can pilot and see results for quickly – plan it and do it!

- Plan. Set out all the details. What new approach will you try? With whom and covering which topic? By which date must you be ready? What will your fallback plan be if your first attempt does not achieve your stated objectives? How will you evaluate the successes and failures of your attempt? As time goes by and you gain confidence in trying new ideas online you can be more flexible and formulate less-rigid plans, but at the start of your journey detailed planning will make you feel more secure in your actions.

- Get permission. If you are considering a large change make sure you have all the relevant approvals in place. Take time to prepare give those involved all the information they may need; explain the benefits as well as the risks and show that you have thought long and hard about the change and its potential benefits for learners. If permission is not granted ask for feedback and adjust your proposal before seeking approval again.

- Don’t be a perfectionist. Any changes to your practice will require adjustments along the way. Observe what works and what doesn’t. Modify and then try again.

- Reflect honestly. Reflect on what you have learned; reflect after further reading; reflect again after discussing the change with students or colleagues, then again after giving it a try.

- Collaborate. Share your initial attempt and your reflections upon it with colleagues or networks. They may spot additional adjustments that you can make and will be better placed to comment objectively on what went well and what did not. The course community of practice Facebook group provides a space where you can share and discuss ideas.

- Listen to students. Ask your students for their impressions of what was tried and their ideas for change. Often they will see the positives of ‘trying something different’, even if things didn’t go exactly as you had hoped.

- Learn from failures. Some changes work, some don’t. Sometimes the technology fails, sometimes the pedagogy is not a good fit; sometimes external factors have an influence. When something goes wrong don’t lose your enthusiasm and curiosity about online practice. Instead, think about what you have learned and how that will make your next steps better.

- Celebrate success. It may be a small change, but if it works, allow yourself to enjoy the success! Share your story with colleagues and your networks. Build upon your success to try something else or to repeat the first change in a different context.

6 End-of-course quiz

In this final quiz, you will check what you have learned throughout the course. In order to earn the certificate of completion and a second digital badge you must:

- have gained the first 'Skills for Prosperity: Online Education' badge, which was associated with part one of this course

- have studied sessions 5–8 of the course

- score 50% or more on this final quiz of the course.

To enable you to prepare for the quiz this session contained less new material than the previous ones. Take some time to look back across the entire course and the notes you have made before starting the quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab, then return to this session when you’re done.

Summary

Congratulations on completing the course!

In this final session you have looked at ways in which you might change and develop your practice as an online educator. You have considered the different ways in which an internet connection can benefit learners and the expectations about learning in a classroom that may no longer apply online. You have also reflected on the skills that learners need when they move online, and been introduced to learning design and its uses.

Your final activity of the course is to see how Rita’s getting along and to reflect on your learning. The community of practice Facebook group will continue once you have finished the course, so you will have opportunities to further develop your practice alongside staff in similar roles in other universities across Kenya.

Activity 8.5 Reflecting on progress

Watch the video or read the transcript. In it, Rita reflects on this session from her perspective as an educator. Take some time to make notes on the following questions:

- How does what you have learned in this session relate to your own role?

- What changes, if any, could you make to your practice or to the wider practice at your university as a result of what you have learned?

Transcript

Now that you have completed the course, we would appreciate you taking part in our end-of-course survey to provide any feedback from your experience.