Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 5:40 PM

Listening to young children: supporting transition

Introduction

In this free course, Listening to young children: supporting transition, you will explore ways of listening to children in order to support their experiences of changes or transitions. Such transitions can involve many dimensions including familiarisation with new cultural practices, the development of new relationships, and potentially a shift in identity, for example from being a ‘nursery child’ to being a ‘pupil’. During the course you will explore how listening to children as they go through such fundamental transitions can enable adults to personalise support, and ensure children can become confident, active participants in a new setting.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course E229 Listening to young children: critical reflections.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

discuss how listening to children as they prepare for and experience transition can help them to make meaning of their new situation

outline the discontinuities that children can experience as they transition to new environments

explain how boundary objects and learning stories can provide an opportunity to listen to children’s perspectives about their identity

outline the ways listening can contribute to the positive experiences of children making complex transitions.

1 Supporting unique transitions

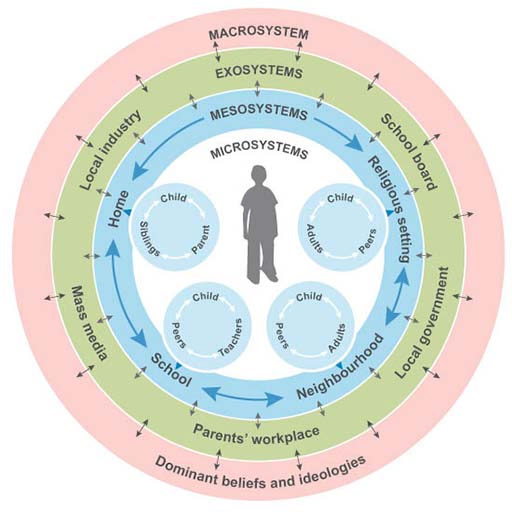

The diagram above, conceived by eminent psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner in 1979, represents a way of understanding children’s development and experiences. It illustrates the complexity and range of transitions that a child might encounter on a daily basis as they move between different situations or environments. The model also highlights the value of listening to different people’s perspectives in order to support the child as they encounter such transitions. For example:

- A child operates in a number of microsystems such as home, neighbourhood and nursery, in which they have different roles and relationships. Children can develop shared understandings about new microsystems, in dialogue with others who listen and respond.

- Parts of a child’s microsystems interact within the wider mesosystem. Parents or carers and nursery workers sharing information by talking or passing on written documentation is an example of such interaction. Such sharing of information and dialogue can help children to experience a smooth transition as they move between microsystems.

- The exosystem consists of environments in which the child has no direct involvement but which might influence their experiences. A change in a parent’s working hours, for example, might require a child to move into different childcare settings. Listening to children and their carers can highlight the impact of such changes.

- The macrosystem refers to the wider cultural values, laws and customs that filter through the other layers to impact on the child. Children who move between different countries, for example refugee children, may experience such significant cultural shifts and transitions.

1.1 Listening to multiple perspectives

The sociocultural thinker Barbara Rogoff (2003) maintains that any child makes an active contribution to the environment or social community of which they are a part. Adults learn from them as much as they learn from us. Therefore supporting children’s transitions should not only draw on other people’s perspectives it should also involve listening to the child themselves. The following case study highlights the importance of listening to multiple perspectives.

Box 1 Case study

Researcher Julie Medhurst investigated the experiences of twin boys Michael and Martin, aged 2 years 6 months, as they made the transition from the ‘Toddler’ room to the Nursery at their Children and Family Centre (Medhurst, 2014). She interviewed the boys’ mother, family worker and new nursery worker, and found that pre-transition visits to the nursery with the boys and their family worker, had been valuable opportunities to listen to their needs and interests, to build continuity and address concerns.

To extend their listening further the collective group also watched videos of the boys playing in both the ‘Toddler’ room and the nursery, reflecting on their body language, well-being and engagement. The boys’ mother noted that Martin took the lead in the new setting which was enabling for Michael; others in the group considered whether transitioning separately may have been more beneficial.

In this example listening to the different perspectives on the situation produced valuable information about the boys’ experiences that could inform their future transition. By engaging directly with the boys’ reactions to their environments, the group valued Michael and Martin as active contributors to their new context.

Summary points

- Bronfenbrenner’s ideas about ecological systems highlights the complexity of influences on young children’s daily experiences.

- Listening and responding to children as they prepare for, and experience transition, can help them to make meaning about change.

- Listening to multiple perspectives, including the child’s, and making connections between different situations can enable practitioners and families to support children’s smooth transition.

Activity 1 Personalising transitions

Read the following quotation from researchers Hilary Fabian and Aline-Wendy Dunlop who listened to children, families and practitioners to identify ways of supporting children’s transitions. Although they summarise the needs of children moving into formal school, their ideas are equally relevant for a child starting other settings such as a nursery or childminder.

For children to gain a positive view of school and feel confident they need:

- a good knowledge of the layout of the room and some knowledge of the setting building

- a knowledge of the practitioners and the way they think

- an understanding of the language and communication used in the setting

- an idea of the nature of the activities that take place

- strategies to make friends, and

- a sense of the setting culture.

The list is reproduced in the table below. For this activity think about a child you know well, and think about a transition they will make in the future. In the ‘strategies’ column of the table, record any ideas you have about how the child can be supported to have this positive view of their new setting, for example by meeting a new practitioner, and consider the opportunities for listening that the strategy provides.

On the right-hand-side of the table, record any potential barriers that might hinder the strategies you identified, these might be practical, or related to social, cultural or physical factors. One line of the table is completed with an example.

Alternatively you can reflect on a past transition that a child you know well experienced. In the table record the strategies that you noticed were in place and the barriers that were encountered.

| Needs | Strategies | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| A good knowledge of the layout of the room and some knowledge of the setting building

| ||

| A knowledge of the practitioners and the way they think

| ||

| An understanding of the language and communication used in the setting | ||

| An idea of the nature of the activities that take place

| ||

| Strategies to make friends | Offering pre-visits to the setting can provide opportunities for children to meet new peers. A practitioner who listens to children’s interests can support children to make connections with like-minded peers.

| Not all children will be available to attend pre-visits and may be disadvantaged by the lack of socialisation opportunity.

|

| A sense of the setting culture. |

Discussion

A child can be supported to make meaning about their transition experiences through visits, and dialogue between the family and practitioners. Play experiences during visits should be in line with the usual activities on offer but also can be adapted to suit children’s individual interests. The individual child’s ways of communicating need to be clear to everyone not just through discussion but also through experiencing activities together. You probably had such ideas recorded in your list but remember supporting transition is not simply about preparatory visits or meetings. Listening to the child before and during transition is essential.

When adults listen to, and respond to a child, and those who know the child well, they can develop shared understandings about new settings. The aim of listening here is to create continuity for the child and a sense of connection as they move between environments. Additionally you will not know whether the physical strategies and arrangements that you have put in place have been successful unless you continue to listen to the child and their family.

2 Listening for discontinuity

In the previous section you considered the value of listening during transition to create continuity and active participation. Where there are barriers to developing shared understandings, such as differences in language or a lack of time or resources, children’s experiences can lack connection. Change itself can result in a feeling of discontinuity; new environments, people and cultural practices can be stimulating but they can also be a source of anxiety (Dockett and Perry, 2007). It is only through careful listening to a child that a practitioner can identify which aspects of their transition might be acting as a barrier to participation.

Researcher Hilary Fabian (2002) suggests that discontinuities fall into three categories:

- Physical – change in physical environment, size, location, number of people.

- Social – change in primary and peer relationships.

- Philosophical – change in ethos and values.

In the following examples from research conducted by Ita L. McGettigan and Colette Gray (2012), children reflect on their experiences of transitioning into schools across rural Ireland. As you read the children’s views, consider how listening enabled the children to express barriers to their participation.

2.1 Examples of discontinuity

Physical discontinuities

Were you worried about starting school?

Kiera: Only ‘bout playing in the yard where the big ones [older children] could get me?

Listening to Kiera revealed her fear of spaces and the presence of bigger children. Such fears could be addressed with focused support in ‘the yard’ to build Kiera’s confidence.

Social discontinuities

Mairead’s experience of changing relationships which she expressed by drawing and talking were both exciting and distressing:

…Mairead recalls how ‘my mommy and daddy took me [to school] ...I didn’t ...I didn’t ...I was crying’ [Mairead starts to cry]. Her distress is captured in her drawing which shows her crying on her first day:

Did you know any of the other boys and girls?

Mairead: [Stops crying]. Yes, I remembered Eth.

At this point, Mairead starts to draw again and produces a second, happier picture which she tells us shows her ‘playing with my new friends’

Mairead’s drawings and dialogue suggest that she was actively making new friends, but saying goodbye to her parents had been distressing; a practitioner might focus support on Mairead’s entry to school.

Philosophical discontinuities

Is preschool different from school?...

…Dara: You need to write at big school and you can play at wee school.

…Fay: I hate big school and I loved playschool because you get to paint in play school with toys and all you have to do is colour, you get to paint, eat sweets or take lunch. There’s what I love.

The researchers highlighted that infant classrooms tended to be formal and goal orientated, in contrast to children’s play-based home or pre-school experiences; a discontinuity that the children found undesirable.

2.2 Listening to everyone

You will also notice that all the children in the examples from the research were able to answer questions and talk about their experiences. Consequently listening was relatively straightforward. What about children who do not yet use spoken language, how would you listen to them? It is likely that they will encounter the same discontinuities when moving from home to their first nursery or child minder and so tuning into what they are experiencing will be vital. For younger children listening will involve more observation to provide insight into their situation as well as drawing on the perspectives of others who know them better than you, for example their parents or carers.

Summary points

- Listening to transitioning children can highlight barriers to their active participation in a setting environment, and identify areas for adult support.

- Where there are barriers to developing shared understandings between different environments, children’s experiences can lack connection.

- Areas of discontinuity for children can be physical, social or philosophical.

- Listening can involve ongoing observation and asking questions of others that know the child more closely.

Activity 2 Identifying perspectives

In Section 2 you considered some quotations from McGettigan and Gray’s research, featuring the voices of children as they started school. In this activity, you are given more views from the children who have been involved in transition from pre-school to first school. Some recall experiences that supported continuity in their change and some describe feelings of discontinuity.

Read each statement then match it to the category using ‘drag and drop’ to complete the table. There is one example of each category and one has already been matched for you. When you have finished you can check your answer by clicking ‘Reveal answer’.

Remember the categories of discontinuities are:

- Physical – change in physical environment, size, location, number of people.

- Social – change in primary and peer relationships.

- Philosophical – change in ethos and values.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 6 items in each list.

‘School had a sandpit and water tray like pre-school and a dressing up box’

‘I didn’t know anyone to play with outside’

‘We have to listen to story like in nursery’

‘There were lots of rooms and buildings- at nursery only one’

‘Me and Mum pick up my brother so I know the teacher and she knows me’

‘We only played with the toys for a bit then it was tidy up’

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Social continuity

b.Physical continuity

c.Physical discontinuity

d.Social discontinuity

e.Philosophical continuity

f.Philosophical discontinuity

- 1 = b,

- 2 = d,

- 3 = e,

- 4 = c,

- 5 = a,

- 6 = f

Discussion

The impact of these continuities and discontinuities as expressed by these young children will have a different impact on each of them depending on their individual characters and on-going experiences. During transition experiences the situation is likely to shift and change quickly. It is therefore useful to be aware of the potential discontinuities that do arise but essential to keep listening to the children to try to understand and support their shifting experiences.

3 Identities across boundaries

In Section 1 you considered the value of supporting children’s transitions by listening to their perspectives and supporting them to be active participants in new settings. Inviting children to bring special objects that reflect their interests, from home or other settings provides an opportunity to listen to their ideas about their identities. Often referred to as boundary objects, these physical objects such as a special toy, book or treasure bag of items can be carried between the boundaries of home and setting, and their meanings shared with others. By listening to children’s perspectives, practitioners can highlight connections between children’s identities and opportunities to build on their interests within the new social community. Remember listening can involve asking the child about their special object or for some children watching how they play or respond to it.

3.1 Learning stories as boundary objects

Some children might bring a portfolio of ‘learning stories’ into a new setting which also function as boundary objects. These documents, often collated in previous settings, use photographs and narrative observations of a child’s experiences to support them to reflect on their activities (Carr and Lee, 2012). Below is an extract from a book of learning stories that Henry brought with him as he moved to a new group room in his nursery.

Box 2 Henry to the rescue!

Henry, I really enjoyed listening to your story about the people trapped at the airport that you told today when playing on the car mat. You sorted the vehicles into ambulances and fire engines and carefully moved them around the roads to complete their rescue mission. It was kind of you to let your friends join in with your story. You shared your ideas with them, and listened to their ideas too. It was really clever of you to send the biggest ambulance and fire engine to the rescue, and you explained to your friends, that these would have the most room for people who might be hurt, and be able to carry the most water.

There are different ways of writing learning stories, but the principle is to create a narrative that engages a child in reflecting on their learning. In Henry’s story, the use of photographs and personalised dialogue support him to recall his perspectives and to know that his learning is valued. He has been used to sharing such stories with practitioners and his parents throughout nursery. They have been an important tool for listening to him and sharing such stories in a new room will help unfamiliar practitioners make new connections with him. By sharing the story the practitioners will recognise that he is a problem solver, collaborator and explorer. They may be prompted to introduce him to the spaces and places where his skills might be applied and his interests fulfilled, so supporting his transition into his new environment.

The value of using learning stories as boundary objects is highlighted in the following example from Carmen Huser, Sue Dockett and Bob Perry’s research which followed one group of children’s transition from kindergarten to first school in Germany.

… the kindergarten educators developed portfolios for children, consisting of learning stories to highlight children’s competence, learning and dispositions. Collaboration resulted in the adoption of the same approach by school educators. These portfolios accompanied the children to school, and were used both as ‘icebreakers’ in discussions about school readiness, and as the basis for ongoing communication with educators, families and children. Children, who had been involved in documenting their own learning, were excited to share the portfolios with school teachers and to talk about their kindergarten experiences with teachers and new classmates…In many ways, the learning stories provided a meeting place where all participants could gather to share their own achievements …

You can see from this example that listening to children through their learning stories, can support them to make meaning with others about their identity as learners as well as develop an understanding of the role they might adopt in different settings.

Summary points

- Boundary objects are physical items that can be carried between the boundaries of home and setting, and their meanings shared with others.

- Sharing the meaning of boundary objects can provide an opportunity to listen to children’s perspectives about their identity.

- Learning stories can be used as boundary objects. When they are shared they enable children to make meaning about their place in a new learning community and help others include the child more readily.

Activity 3 Thinking about boundary objects

Now look at both the lists and reflect on any connections between the type of objects that were chosen and the reasons why they were selected.

Discussion

Although very different, both lists are likely to have the following aspects in common: both let others know about people that are important; both feature things that interest or motivate; both include things that calm and sooth.

Sharing such objects would support listening to you as the new person and establish a clear identity for you in the new group. Of course as an adult there would have been things that you did not want to share – aspects of your identity that you did not initially want to reveal to new people. In choosing boundary objects with young children you should also take these issues into perspective. Boundary objects should support being listened to and so settling in a new environment rather than add to your feeling of alienation.

4 Complex transitions

In Section 1 you were introduced to Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model (1979), which illustrates that some children, for example those from refugee families, can encounter significant changes in dominant values, beliefs and customs at a macrosystem level. Such children can experience cultural and linguistic shifts as well as the usual challenges of transition experienced by all children.

Children engaged in transitions that involve significant cross-cultural meaning making, may vary their levels of participation over long periods of time as they settle, often with the support of a long-term listening partner. Building a relationship based on listening and trust can provide children with a point of contact where they can share their perspectives and make meaning about their transition experiences

4.1 Case study: suitability and trust

Researchers Kris Kalkman and Alison Clark (2017) draw on the idea that children need to experience a sense of belonging or suitability in order to be active participants in their communities (Woodhead and Brooker, 2008). The researchers suggest that children can reflect on their own degree of suitability when negotiating their role in social play, and it is in this context that the presence of a listening adult might support children’s meaning making.

Consider the following narrative from Kalkman and Clark’s research in which they focus on the role-play experiences of Bahja, a 4 year old girl who joined a Norwegian day care setting from the Middle East. Bahja spent 3 months in the setting’s Badger Group learning about Norwegian language and culture but then joined the Fox group with other children in their final year of day care before school. As you read the extract, note how Bahja seems to reflect on her own suitability to play within the group, and how she approaches a listening adult (Kris Kalkman, researcher author who has spent considerable time listening to children in the setting) to support her play on the periphery, and share in her meaning making about her cross-cultural experiences.

Princesses and Dragons

… As the girls put on their pointy princess hats and silky gowns, they negotiate their roles, discussing and explaining to each other what they will do and how they will do this. When done, they instantly begin their play, some running around as princesses yelling that the dragons are coming, others pretending to be the dragons, ready to capture the princesses and take them to their prison towers. As the girls play, it seems that none of them have noticed that Bahja has arrived in the Fox group this morning.

… having received no invitation to join the girls, she walks into the group and with a somewhat sad expression on her face, she passes the girls by, unnoticed. Walking into the group, she spots Kris, the first author, observing her. Bahja begins to smile and walks over to him. Passing him by, she stands behind him and opens a large wooden chest. From this chest, she takes up a silky gown frequently used by the other girls in their role play. Holding it in front of her, she examines it closely. Then she puts on the gown, and when she is finished, she smiles at Kris, asking him, ‘Do you want to play with me?’ ‘Certainly, Bahja,’ Kris replies, and instantaneously, Bahja starts narrating and takes more content from the chest. Even though enthusiastically narrating, the first author notices how Bahja struggles with finding Norwegian words and as such supplements with Arabic and body language to communicate her intention whenever she notices that Kris doesn’t understand her. But, without any doubt, the first author understands that Bahja is narrating her own version of the princess and dragons role play, as routinely performed by her peers.

Kalkman and Clark suggest that Bahja does not quite identify herself as ‘suitable’ to engage fully in this particular play, perhaps because she does not yet align with all of the social and cultural references. She does however find support in her relationship with an adult who she knows will listen, and integrates some of the group play activities with her own cultural expressions, enabling a sense of participation and belonging.

Summary points

- Complex transitions can involve linguistic and cultural shifts, listening to individual experiences can support children to explore their sense of belonging.

- Developing relationships with children based on listening and trust, can provide a context for them to make meaning of their transition experiences.

- Children who are making significant shifts in transition may vary their levels of participation over long periods of time and often look for the support of a long-term listening partner.

Activity 4 Listening for ideas to support transition

Part 2 Planning to support transition

For the second part of this activity use the insights that listening to Rory and Tanya have given you and list 3 pieces of advice that you would give to a practitioner who is planning to support a transitioning child or group of children from Reception to Year 1. Then add three more suggestions that you would make based on the listening approaches that you have learned about in this course. Use the space below to record your points:

| Ideas to support transition |

|---|

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

Discussion

Because of the importance that Rory and Tanya highlight about play that they particularly enjoyed in Reception, it would be appropriate to ensure that the preferences of the children who are making the transition are known. These activities could then also be on offer during any settling in periods. Information about friendship groups for children moving up would also be useful so that children could retain their own support network as they experienced transition. Rory also referred to the shared visiting that took place between the class groups and so it would be helpful to replicate this approach.

You will have a number of other ideas about how practitioners could also support transitions. These could have included:

- Preparatory sessions with the child and their family to listen and respond to multiple perspectives on children’s needs and interests.

- Time spent listening to children’s views in the early days of transition to reflect on potential barriers to participation?

- Promoting the value of listening to children as they share their boundary objects that reflect their wider identities.

5 Further thinking and discussion points

To help you to reflect on your learning you can think about the following questions in light of your reading of this course.

- Why is it important for children to feel that they belong in a new community?

- How do you think the nature of transitions for young children are becoming more complex?

- How can relationships based on listening be maintained over long periods of time?

- Why are some children more likely to be listened to than others?

Activity 5 Quick quiz

- Researcher Hilary Fabian (2002) suggests that discontinuities fall into three categories: physical, social and philosophical. Can you match the category to its definition? Use ‘drag and drop’ to do so.

Reviewing Section 2 will help you complete this question.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 3 items in each list.

Social discontinuity

Philosophical discontinuity

Physical discontinuity

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.change in ethos and values.

b.change in physical environment, size, location, number of people.

c.change in primary and peer relationships

- 1 = c,

- 2 = a,

- 3 = b

Answer

| Social discontinuity | change in primary and peer relationships |

| Philosophical discontinuity | change in ethos and values. |

| Physical discontinuity | change in physical environment, size, location, number of people. |

a.

objects that mark out where children can go in new settings.

b.

physical items that can be carried between the boundaries of home and setting, and their meanings shared with others.

c.

learning documentation that is shared between settings when children moved.

The correct answer is b.

Answer

physical items that can be carried between the boundaries of home and setting, and their meanings shared with others.

Conclusion

In this free course, Listening to young children: supporting transition, you have reflected on the value of listening to children as they transition and become active participants in new communities. You have considered the merits of listening to those who know children well, and have recognised the child as an active contributor to community culture. You have thought about the role of listening in identifying discontinuities in children’s experiences. Your attention was drawn to the value of listening to children as they share the meaning of their special objects, in order to make meaning about their role and identity within the new context. Finally you considered the place of listening in complex transitions, as a long-term approach to supporting children in their cross-cultural meaning making.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course E229 Listening to young children: critical reflections.

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by John Parry.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

Course image: © Fatcamera/Getty Images

Figure 1: Adapted from Penn, H. (2014) Understanding Early Childhood: Issues and Controversies, 3rd edn, Maidenhead, Open University Press.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don't miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.