Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 4:11 PM

Week 2: What is autism like?

Introduction

By now you should begin to have a fair picture of autism. This week looks in more detail at key characteristics, giving particular attention to difficulties and challenges, and also to strengths, and to how these may vary between individuals and groups.

Now watch the video in which Dr Ilona Roth introduces this week’s work.

Transcript

By the end of this week you should be able to:

- formulate a more detailed picture of autism characteristics and the challenges they may pose for the individual and their family

- have insights into autistic strengths, including special skills and outstanding talents

- appreciate ways in which the profile of difficulties and strengths varies between different individuals

- understand that the autism spectrum encompasses striking IQ differences between individuals

- recognise the presence of accompanying problems such as epilepsy or dyslexia in some cases.

1 Autistic traits and neurotypicality

As you saw in Week 1, autism involves characteristic traits – ways of behaving and interacting with the world – which differ from those of the neurotypical population.

Given the varying pattern and impact of these differences in autism, specialists need clear and explicit criteria to evaluate whether, say, one person’s limited use of spoken language and another person’s excessively verbose speech both ‘tick the box’ for an autism-related symptom. Diagnostic criteria are developed, piloted and refined over a period of years by specialist working groups. You will explore them in more detail next week. Meanwhile, watch this clip in which Arabella describes how she came to realise that her daughter, Iris Grace, might be different from other children.

Transcript

2 Social characteristics

Common social differences between young children with autism and

2.1 Interacting and communicating non-verbally

At the age when typically developing children start to play together and make friends, an autistic child may prefer to play alone; the play may seem rigid – for instance a child may prefer to line up his play figures rather than using them for a pretend game, such as a tea party.

Further differences that may impact on social interaction at any age include problems with

2.2 Communicating with language

In autism, difficulties in using language for communication range from the total absence of speech (without the use of gestures to compensate) to the use of language that is excessively repetitive or unusually stereotyped. Some may only speak in certain circumstances, such as with people they know very well. This is known as

Even when an autistic person has fluent language, there are likely to be other problems of communication, such as difficulty in taking turns when talking to others.

2.3 Taking things literally

Another noticeable language difference is taking the meaning of words, phrases and sentences literally – for instance a child told ‘pull your socks up’, meaning ‘try harder’, may assume that it is their socks which need attention. When an autistic boy called Michael Barton was at junior school, he devised a strategy to help him decode the non-literal expressions that he found so strange. He would note the expression and draw a picture of it, followed by a sentence explaining what it meant. As a young adult he has published his delightful drawings to help others on the spectrum (Barton, 2012).

Activity 1 Misunderstanding what people say

In this clip a young man explains why taking things literally can make it difficult to understand jokes. Watch the clip and then write a few notes explaining how an ironic or sarcastic comment might lead to a similar misunderstanding (hint: think about the words and the tone of voice when a person says something sarcastic).

Transcript

Discussion

When a person speaks ironically or sarcastically, they may say one thing, but in a tone of voice which indicates that they mean something else. For instance ‘It’s a really nice day today’ when it is actually pouring with rain, or ‘You are so good at English’ when it is a field that the person struggles in. An autistic person listening to such a comment may take it literally, and not notice or understand the non-verbal cues provided by the tone of voice, which indicate that the speaker means something different from what he or she says.

Literal-mindedness can also mean that an autistic person says things which others find rude or hurtful, because they don’t realise that being completely truthful and candid isn't always polite. For instance, telling someone who has just cooked you a meal that you don’t like their food is not usually the best approach if you are invited for dinner. In general, autistic people tend to lack intuitive understanding of the unspoken social rules that apply to different situations, leading to social ‘faux pas’ or blunders. This lack of insight into other people’s thoughts, feelings and points of view is often thought of as a ‘Theory of Mind’ failure, a psychological concept which will be covered in Week 4.

To gain an insight into how an autistic person may quite unintentionally upset others by failing to understand social rules, watch the two video clips below.

Transcript

(Daniel arrives at reception desk)

(muffled background noise)

(Daniel peers at name tag)

CAPTION: A person with autism may find it hard to understand social etiquette.

Transcript

(Daniel sits down)

Conversation about relationship break-up between other 3 people at table

Don't worry about it; he was an idiot anyway.

Plenty more fish in the sea.

I don't understand it, I just don't understand it.

There's nothing to understand, he's just playing games. He wants you running round after him.

There's something wrong with me.

Just count it as his loss.

Why would he say he loved me and why would he dump me?

Because he's a man.

Why has another one dumped me?

(awkward looks)

CAPTIONS: A person with autism may take you literally. They don't mean to be rude.

2.4 Socialising

Finally, autistic people may not always value socialising as much as others. Children in particular may react strangely to things like birthday parties and Christmas gatherings of family, finding the changes to normal routine, the comings and goings and the surprise of presents overwhelming. Yet autistic people can still experience loneliness. It should not be assumed that they want to be left alone, but they may need help to socialise, and also ‘recovery time’ from socialising, since constantly trying to work out the meaning of what others say and do can be exhausting and stressful.

For further discussion of social and communication characteristics in autism, see Roth et al. (2010), chapter 3.

3 Non-social differences

3.1 Repetitive behaviour and routines

Some children incessantly twirl their fingers or flap their hands. Such movements are often known as

3.2 Special interests

Many autistic people, both children and adults, develop an extremely intense

Neurotypical people may struggle to understand the attraction of these unusual special interests, and parents may express frustration at the amount of time their child spends on their interest to the exclusion of other activities, and at the incessant questioning that may accompany it. Some autism practitioners argue that special interests are detrimental because they exacerbate social isolation and suppress other opportunities for learning. Yet the individual with the interest may find their chosen pursuit fulfilling and comforting (Grove, Roth and Hoekstra, 2016), and other practitioners believe that special interests can serve as effective building blocks for learning. For instance, teachers can make use of the special interest to develop reading, writing and other skills, or simply as rewards for attending to other tasks. Finding others who share the same interest may also lead to developing a circle of friends. There is much still to be explored in this field.

Activity 2 Special interests

Read the two extracts in which autistic people describe their special interests. Do you find anything unusual about these interests – either the topics, or the way they are pursued? Make a few notes.

In fourth grade, I was … interested in both dinosaurs and astronomy, especially since this was the time of the Voyager flybys of Jupiter and Saturn. My appetite for information was voracious and I would clip or photocopy everything I could find on the subject in the newspaper, magazines, academic journals and books. I think my interest in dinosaurs waned at this point, though I remember an occasion when I went to the neighbourhood pool and I went up to total strangers asking them to ask me any question about dinosaurs because I felt I knew everything about them.

My parents and my family weren’t really into reading and the sorts of things I was interested in so it was difficult and it was hard for my family to appreciate the passionate way that I got involved with things. They didn’t understand why anyone would want 100 mice, for example, little white mice with purple eyes that I bred in Smiths Crisp tins covered with chicken wire in the garage, and they didn’t understand why I collected beetles or why I would line up my insects and race them. My sisters wouldn’t do those sorts of games, they played tea parties and dolls houses and I wasn’t interested in those sorts of things.

Answer

The first extract describes special interests which many other people share. But the engagement with the interest is very intense, and the attempt to involve strangers in ‘quizzing’ the writer is perhaps unusual.

The second extract describes passionate involvement in various interests, including mice. Keeping one or more mice as pets would not be that unusual as a childhood interest. But Wenn’s interest focused on one particular kind of mouse, and breeding lots of them suggests a strong drive to collect things, which Wenn acknowledges in his reference to beetles. Again, there is an intense and somewhat unusual way of engaging with several topics of interest.

3.3 Unusual sensory responses

For many people on the autism spectrum, sensory information (received via eyes, ears, touch etc.) evokes either stronger or reduced responses compared to neurotypical individuals. For instance, autistic people may dislike fluorescent lighting because they can perceive the flicker. This dislike can be so intense that they will refuse to enter a room with that type of lighting. They may need labels cut off clothes as they find the sensation unbearably irritating. One of the reasons Temple Grandin gives for wearing her distinctive cowboy-style shirts is that they are made in very soft cotton, the only texture she says she can tolerate next to the skin. Such accentuated reactions are known as

Profound aversion to the taste or smell of particular foods is also common, and yet some autistic children seem to crave particular tastes such as sugar. Similarly, when it comes to sound, one person may find the noise of traffic in the street unbearable, but another may seem immune to the noise. Apparently lowered responsivity to sensory stimuli is known as

Listen to this clip of Arabella, mother of Iris Grace, discussing how Iris Grace’s sensory responses fluctuate and change over time.

Transcript

4 Reactions to stress

Autistic people may experience enormous stress and anxiety as a result of any of the traits just described. Social situations, the disruption of familiar routines and activities, or exposure to aversive sensory stimuli such as textures, smells and sounds, may be confusing, overwhelming or even frightening. In such situations, both children and adults with autism may resort to activities or behaviours which seem particularly unusual to others, but which help the person to manage and reduce the stress they are feeling.

Listen to Arabella again:

Transcript

Sometimes, in response to an unbearable level of stress, an autistic person may have a ‘

During our first hour on the road, Elijah rifled through hundreds of stickers I had brought along to keep him busy in the car. He feverishly peeled them and pasted them onto a large piece of cardboard like a small machine with his strict and narrow concentration. In the rear-view mirror, I saw the waxy paper backings of the stickers piling up in the back seat like fluffy patches of snow surrounding him. When he had peeled the very last sticker from its paper he let out a screech. Quickly, I popped the Pinocchio soundtrack into the tape player to redirect him, but to my dismay, I had forgotten to rewind it.

… ‘REEE…WIND’ he bellowed when he suddenly heard Pinocchio’s voice singing mid-song.

Stress reactions are likely to happen regardless of the person’s level of functioning. For instance, high-functioning teenagers with all the intellectual skills necessary to attend university, are quite likely to struggle with living away from home, dealing with personal care and the constant pressure to socialise. It is important that their tutors or mentors are aware of the additional emotional strains they are under, and that the university has support strategies in place.

5 Skills and talents

While some aspects of autism undoubtedly present difficulties or challenges for the individual, you have seen that others may simply be unusual such as an eccentric special interest. Some autistic people also have enhanced skills, such as very good numerical or mathematical skills, excellent memory for names or facts, or enhanced visual and spatial skills. Since such skills often exist alongside marked difficulties, they are sometimes called '

5.1 Skills

Often the same autistic characteristic which can make life difficult in some situations – for instance, the tendency for

Another example is the need for structure, routine and repetition. Difficulty adapting to change may go with the capacity to persist in tasks for which others would not have sufficient patience or attention span. Again, this is proving invaluable in some industrial jobs.

The same social naivety which, as we saw earlier, may lead a person into awkward social situations, means that autistic people tend to speak their mind with great honesty. In a world where some people resort to dishonesty and deception to get what they want, such honesty can and should be highly valued. An employer, for instance, may place particular trust in autistic staff members.

5.2 Exceptional talents

While pursuing their special interest (see the previous section), an autistic person is likely to develop an exceptional knowledge or grasp of their favoured topic and so become an expert. A minority of autistic people show truly

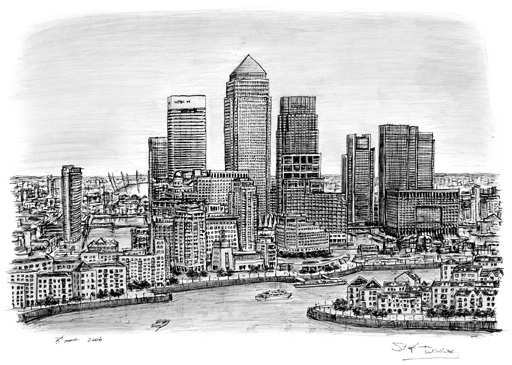

For instance, Stephen Wiltshire did not speak until he was 5 years old, and was diagnosed with autism. But he showed an outstanding talent for drawing from an early age, and without being taught. Ever since then he has been drawing complex cityscapes such as Canary Wharf, producing impressive and astonishingly accurate works after just a few minutes studying the subject matter.

Watch these clips to learn more about the work of talented autistic artists.

- Stephen Wiltshire and his sister talk us through as he makes a drawing of New York City.

- Derek Paravicini displayed a similar early and self-taught talent for the piano. As an adult he has an impressive musical repertoire, is an accomplished jazz pianist and has played with Jools Holland among others. Here he improvises on a well-known Brazilian melody.

Such exceptional talent, surpassing that of most neurotypical people and coupled with fairly profound difficulties, is often known as

5.3 Creativity

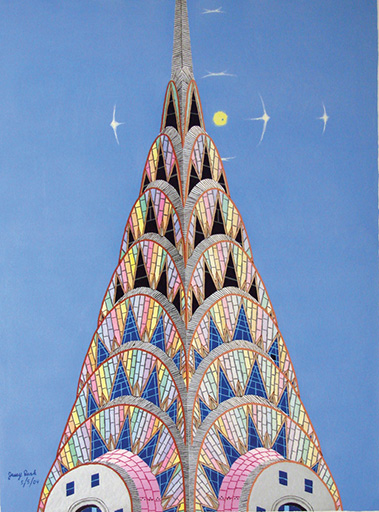

Researchers seeking to explain the basis of exceptional savant talents have suggested that the key underlying abilities are exceptionally accurate memory and attention to detail rather than the ability to generate truly original outputs (Treffert, 2006). This is in keeping with a traditional view, emphasised by the diagnostic criteria, that autistic people lack creativity. However, it is becoming clear that autism is compatible with creativity and may even promote it (Roth, 2007; Treffert, 2009). The American artist Jessica Park makes pictures of well-known buildings which are accurate and yet highly original in their imaginative use of colour.

The autistic artist Jon Adams, who was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome as an adult, reflects on what he sees as the link between his autism and his creativity:

As I viewed the world with a different lens, a differing perspective, the influence on my creativity and making is not surprising. I don’t think there has been a day where creativity hasn’t been the major part of my life. As a child, I was always assembling, collecting and drawing – never letting go of those desires or a pencil ever since. At 6 years old, when asked what I wanted, I said ‘to be an artist’. It seemed the most honest, logical and heartfelt answer I could give.

5.4 Managing exceptionality

The success and public interest enjoyed by exceptional autistic artists is as fulfilling and well-deserved as that of any gifted artist. Stephen Wiltshire has his own gallery in the Mall in London, where people can watch him creating his drawings and buy items from his extensive collection of works. Family members run the commercial side of his business.

Activity 3 Exceptional talent: positives and pitfalls

In what ways do you think exceptional talent might benefit an autistic person and their family? What drawbacks might there be for the individual, and indeed for other autistic individuals and their families? Make a few notes.

Discussion

Working in a field that you enjoy and excel at is likely to be a source of well-being, self-esteem and income. Clearly, exceptionality must be managed so that the gifted autistic person is not exploited or treated as a spectacle.

Publicity for exceptional autistic talent could promote the idea that everyone on the autism spectrum has exceptional savant-type skills, such that autistic people without notable special skills and their parents may feel that everyone expects them to do something exceptional. It is important to recognise and celebrate the exceptional individuals, but not to overlook the needs and difficulties of the majority with autism without extraordinary skills.

Arabella, Iris Grace’s mother, discusses some of the pros and cons of her daughter’s talent in the following clip:

Transcript

6 Further dimensions of autism

To conclude this week, two further sources of variation between autistic individuals will be considered.

6.1 Intellectual ability

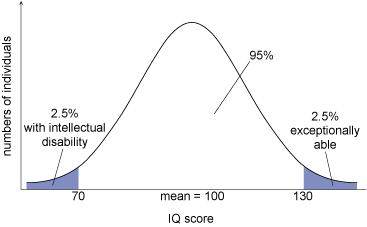

Differences in

When a person has profound intellectual disabilities, as defined by an IQ of less than 70, their autism has sometimes been described as ‘

I have very uneven skills. This is another one of those enigmas. I have University degrees, I am married and I have three grown children. However, I have huge problems with being disorganised, getting lost, using public transport, understanding others, and just the practical interactions of social situations. I think many of you might be saying ‘So what, I do as well.’ I know that neural-typical individuals might have issues in these areas but I would suggest to you that it is the degree of the ‘issue’ that separates us. How many of you need to sit down on the path outside of a supermarket and do breathing exercises because they have changed the tinned soup isle?!

6.2 Accompanying medical and psychological difficulties

In some individuals, autism goes together with other physical or psychological health problems. Perhaps the most common of these is epilepsy. It is estimated that up to one third of people on the autism spectrum may be prone to epilepsy, which is more common in ‘low-functioning’ autism (Viscidi et al., 2013). Some researchers believe that there are common sources for the atypical brain activity associated with autism and epilepsy. Fortunately there is a range of medications and treatment which can help to prevent seizures occurring, but sadly this is not always the case.

Other common problems that co-occur in some cases of autism are

Here Alex talks about his obsession with handwashing, and how he overcame it.

Transcript

Depression and anxiety are also common in autistic people, and there may be many reasons for this. At school, young people with autism often experience bullying, because others perceive them as different or eccentric, and this may lead to low self-esteem and social isolation. Similarly at college, university or in the workplace, autistic people may find it hard to fit in and make friends, suffering all the more because they don’t understand why.

Here Alex talks about his experiences of bullying at school.

Transcript

The NAS (National Autistic Society 2018a; 2018b) has further information about all the problems discussed in this section.

7 This week’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this week by taking the end-of-week quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then return here once you’ve finished it.

8 Summary

This week has provided an in-depth look at social and non-social characteristics of autism, and how they differ in their expression among autistic individuals. Some characteristics present difficulties or challenges for the individual and family members, while others are just unusual ways of engaging with the world and other people. Some traits, such as attention to detail, may be problematic in some situations, but highly beneficial in others. A minority of autistic people have exceptional talents, which may develop early and apparently without learning. Differences in IQ, and in the presence of accompanying problems like epilepsy, is another major source of variation across the spectrum.

You should now be able to:

- formulate a more detailed picture of autism characteristics and the challenges they may pose for the individual and their family

- have insights into autistic strengths, including special skills and outstanding talents

- appreciate ways in which the profile of difficulties and strengths varies between different individuals

- understand that the autism spectrum encompasses striking IQ differences between individuals

- recognise the presence of accompanying problems such as epilepsy or dyslexia in some cases.

Next week considers how the characteristics of autism are used within diagnosis

Now you can go to Week 3.

References

Acknowledgements

This course was written by Dr Ilona Roth and Dr Nancy Rowell.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below and within the course is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this course:

Images

Figure 1: Lisa McKelvie/Photolibrary/Getty Images

Figure 2: © The Open University

Figure 3: from Barton, M. (2012) It's Raining Cats and Dogs Book p43 published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers www.jkp.com

Figure 4: ANDERS KRUSBERG / PEABODY AWARDS https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by/ 2.0/ deed.en

Figure 5: © Stephen Wiltshire

Figure 6: © Jessica Park

Figure 7: courtesy: Jon Adams

Figure 8: The Open University

Audio/Video

1.0: Video: Arabella about her daughter Iris Grace: © The Open University

Activity 1 (1): courtesy Surrey Autism Board http://www.surreypb.org.uk/ surrey-autism-partnership-board.html

Activity 1 (2) Think Differently about Autism: Misunderstanding: courtesy National Autistic Society

Activity 1 (3) Think Differently about Autism: Socially awkward: courtesy National Autistic Society

Video: (3 clips) Arabella talking about Iris Grace © The Open University

Video: (2 clips) Alex talking to Dr Ilona Roth: © The Open University

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Don’t miss out

If reading this text has inspired you to learn more, you may be interested in joining the millions of people who discover our free learning resources and qualifications by visiting The Open University – www.open.edu/ openlearn/ free-courses.