Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 23 November 2025, 3:26 AM

Gender and equity in AMR surveillance

Introduction

This course examines how antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is shaped by both biological and social determinants of health; and what this means for global health policy and practice. You will develop an understanding of the importance of a biosocial approach to health that requires exploration of the social and contextual factors driving and shaping AMR, as well as people’s experiences of AMR and health-seeking across One Health domains.

It is important to identify how social factors create unequal health experiences and outcomes in order to understand how to address these in policies and interventions because they are largely avoidable if the broader social drivers are addressed. You will explore how gender and equity frameworks can be applied to AMR to help you understand and manage inequitable impacts of AMR in your own context.

After completing this course, you will be able to:

- define key terms and concepts related to gender and equity in AMR

- explain how biological factors, including sex, contribute to differences in the effects of AMR

- explain how gender roles, social norms and social determinants influence AMR exposure and experience across different life stages, identifying which social groups may be differently at risk of or impacted by AMR, and how this aligns with key gender equity and human rights mandates

- outline how focusing on equity can strengthen the One Health approach to AMR

- describe the current biases and inequities in AMR data, and explain the importance of disaggregated data in understanding AMR trends across human health, animal health and the environment

- make recommendations for more equitable approaches to AMR interventions and surveillance

- reflect on how gender-responsive and equitable practices in AMR relate to your work.

In order to achieve your digital badge and Statement of Participation for this course, you must:

- click on every page of the course

- pass the end-of-course quiz

- complete the course satisfaction survey.

The quiz allows up to three attempts at each question. A passing grade is 50% or more.

When you have successfully achieved the completion criteria listed above you will receive an email notification that your badge and Statement of Participation have been awarded. (Please note that it can take up to 24 hours for these to be issued.)

Activity 1: Assessing your skills and knowledge

Before you begin this course, you should take a moment to think about the learning outcomes and how confident you feel about your knowledge and skills in these areas. Don’t worry if you do not feel very confident in some skills – they may be areas that you are hoping to develop by studying these courses.

Now use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in these areas using the following scale:

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Neither confident nor not confident

- 2 Not very confident

- 1 Not at all confident

This is for you to reflect on your own knowledge and skills you already have.

1 Why gender and equity matter in global health

1.1 Gender equity is everyone’s responsibility and everyone’s gain

Gender matters in global health. Gender inequality hurts everyone. … Gender determines our positions and roles in society [and therefore] impacts health and wellbeing, influencing both our own individual behaviours – what risks we take with our health, what risks we face and whether or not we seek healthcare – and how the health system responds to our needs when we are sick or need care and support… Gender equality will lead to equal opportunities for people of all genders, everywhere. And health policies and programmes that place gender equality at their core will lead to better health outcomes. Gender inequality is not inevitable.

Evidence shows that gender equality is critical to ensuring sustained peace and democracy around the world (UN Women, 2015). Despite gender and equity being one of the sustainable development goals, women’s rights and gender justice are increasingly politicised (IPPF, 2024; Harper et al., 2025). The Fleming Fund has recognised that gender plays a significant role in AMR and antimicrobial use, and has put gender and equity at the heart of their work as a key strategic shift (Collins, 2023). It is therefore critical that, as you make progress through this course, you reflect on:

- your own positionalities

- the position of your institution with regards to gender and equity commitments and your national context

- identifying any small actions you can take to become a champion for equity, which matters now more than ever.

1.2 What is equity?

Everyone has the ‘right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’ (UN, 1966).

Equity describes conditions in which ‘everyone can attain their full potential for health and wellbeing’ through ‘the absence of unfair, avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or by other dimensions of inequality (e.g. sex, gender, ethnicity, disability, or sexual orientation)’.

-

How does Figure 1 illustrate the difference between equality and equity?

-

In the ‘equality’ part of the figure, all the individuals are given the same type of bicycle regardless of their specific needs. In the ‘equity’ part, each individual is provided with a bicycle that suits their specific needs.

2 A biosocial approach to health

AMR is more than just ‘bugs and drugs’; it’s important to put AMR within the contexts in which we live, work and play.

The

It is increasingly recognised that health and ill-health are shaped by social factors, including economic, commercial and environmental factors. Many researchers have explored these social factors and developed explanatory models.

Next we explore some of the social factors that affect your own health.

Activity 2: What factors influence your health?

Take a moment to consider the factors that influence your health and make a note of them below. Do not include any data that is personal to you in your notes.

Discussion

The factors that you have noted will depend on your personal circumstances. Section 2.1 explores some of these factors further.

2.1 The social and structural determinants of health

The

- income levels

- access to social protection

- education level and opportunity

- job security and working conditions

- food security/insecurity

- access to safe housing

- exposure to harmful environmental factors

- experiences of early childhood development

- stigma and discrimination

- exposure to violent conflict

- access to affordable health services.

These are in turn influenced by broader socioeconomic, political and cultural factors, known as the

- race

- gender

- ethnicity

- age

- sexuality

- class

- disability.

Together, these factors intersect and overlap to produce an unequal distribution of health-damaging or facilitating experiences.

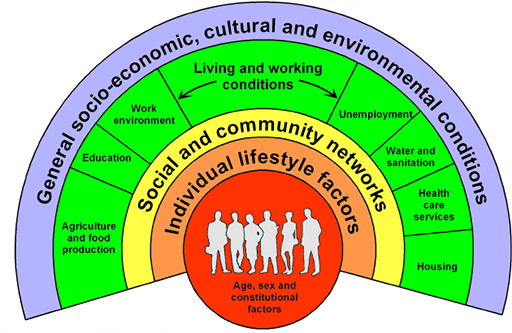

The interrelationships between these social factors, and their influence on health, is illustrated in the Dahlgren-Whitehead ‘rainbow’ model (1991) shown in Figure 2.

-

Now that you have seen the Dahlgren-Whitehead rainbow, can you add any factors that influence your health to your list from Activity 2? Can you match the factors that you have noted to the different parts of the rainbow?

-

The Dahlgren-Whitehead rainbow model places individuals at the centre, with layers of influences on health surrounding them, such as individual lifestyle factors, community influences, living and working conditions, and more general social conditions.

Activity 3 explores some of the structural determinants of health further.

Activity 3: Exploring structural determinants of health

Video 1 is about structural determinants of health. As you watch, think about the following questions:

- Think of an example of a structural determinant of health from your country context. How can it impact

health equity ? - What health system actions or policy actions might address inequities in your context?

- How might gender affect some of the specific factors mentioned in Video 1?

Discussion

- Structural determinants of health can include unequal land rights and access to housing, inequitable education systems, and health systems that do not cover migrant communities or those living in informal settlements.

- Think about actions that cut across sectors, including health, housing, food and land rights.

- Gender can affect a number of structural determinants of health at multiple levels, including socioeconomic position, ease of accessing a health service and occupation and associated health risk factors.

In summary, prioritising health equity is a basic human right and matter of social justice. A biosocial view of healthcare considers how social factors create unequal health experiences and outcomes and supports the design of interventions and solutions to address the root causes of illness. These SDHs are important because they improve our understanding of the conditions that create unequal health outcomes and experiences. They highlight that these unequal outcomes are largely avoidable if the root causes are addressed.

Optionally, you may like to watch Sir Micheal Marmot discussing the importance of SDHs in social justice (American Public Health Association, 2016).

Later in this course you will explore how SDHs can impact the drivers of AMR, but first you will be introduced to gender as a social determinant of health.

3 Introduction to gender as a social determinant of health

Sex and gender are both determinants of health: sex is a biological determinant of health and gender is an SDH. At a global level, SDHs are a more significant driver of health inequities than biological determinants of health.

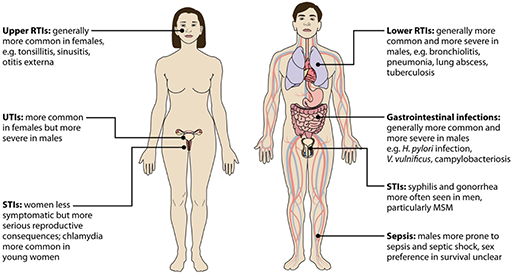

For example, gastrointestinal infections tend to be more common and more severe in males, due in part to:

- the fact that men are more likely to handle food in contexts and ways that carry a high risk of food-borne diseases (a gender factor)

- biological differences (including hormones) in immune response that place males at a higher risk of poor outcomes (a sex factor) (Dias et al., 2022).

Gender is relational and operates at multiple levels.

Gender ... refers to the relationships between people and can reflect the distribution of power within those relationships ... These processes operate at an interpersonal level, at an institutional level and across wider society, in government, the institutions of the state and whole economies.

You may hear the terms ‘gender norms’, ‘gender roles’, ‘gender relations’ and ‘gender mainstreaming’. These concepts are integral to understanding gender as an SDH. Broadly these terms are defined as follows:

Gender norms are a sub-set of social norms that describe how individuals are expected to behave in a given social context and as a result of the way individuals or others identify gender, as women, men and non-binary identities. Gender norms intersect with other norms related to age, ethnicity, class, disability, sexual orientation and gender identity – among other factors – and the way in which individuals experience them (ALIGN, n.d.).Gender roles are behaviours that are widely considered to be socially appropriate for individuals of a specific sex or gender within a culture, dictated by gender norms.Gender relations are the social power relations between people of different genders within households, communities and wider levels.Gender mainstreaming is the systematic consideration ofgender equity in policies, programming and actions.

Gender analysis frameworks can support our understanding of how gender interacts with other processes, such as poverty.

3.1 Gender analysis frameworks

| Who has what? | Access to resources: education, information, skills, income, employment, services, benefits, time, space, social capital, etc. |

|---|---|

| Who does what? | Division of labour within and beyond the household and everyday practices |

| How are values defined? | Social norms, ideologies, beliefs and perceptions |

| Who decides? | Rules and decision-making, both formal and informal |

| How power is negotiated and changed (individual/people) | Critical consciousness, acknowledgement/lack of acknowledgement, agency/apathy, interests, historical and lived experiences, resistance or violence |

| How power is negotiated and changed (structural/environment) | Legal and policy status, institutionalisation within planning and programmes, funding, accountability mechanisms |

The aspects of gendered power relations in Table 1 are also influenced by other diverse social factors. An intersectional health lens highlights the ways that these social factors (including gender, race and class) interact and overlap to influence health.

3.2 Intersectionality

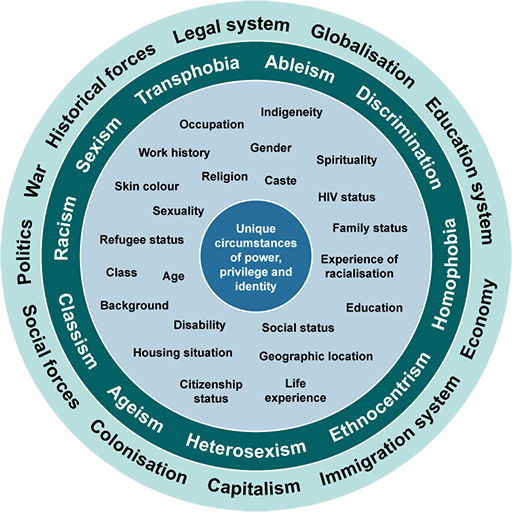

The SDHs overlap and intersect to create specific experiences.

From the centre outwards the circles in the intersectionality wheel represent:

- an individual’s unique circumstances

- aspects of collective identity

- different types of discrimination, ‘–isms’ and attitudes that impact identity

- larger forces and structures that work together to reinforce exclusion.

The intersectionality wheel is not exhaustive, but it includes illustrative examples within each of the circles.

In Activity 4, you will explore how gender and intersectionality impacts infectious diseases and access to healthcare.

Activity 4: Exploring intersectionality

Now watch Video 2, in which Margaret Gyapong from GEAR up (Gender Equity within Antimicrobial Resistance) discusses gender and intersectionality in infectious diseases.

- Consider the points she raises around access to health facilities and the patient–provider links.

- Reflect on the ways in which the health system is gendered and make notes on anything that surprises you.

Discussion

You can see that experiences of health systems are gendered. For example, young women face stigma and discrimination when seeking healthcare, which in turn creates gendered barriers to health-seeking.

Optionally if you would like to learn more on the origins of intersectionality, you may like to watch Kimberlé Crenshaw’s video on the origins of intersectionality (TED, 2016).

Next let’s explore more about how social determinants influence AMR.

4 The social drivers of AMR

In this section you will explore equity in AMR and link this to a people-centred approach to health.

While AMR is a natural process that happens over time, its emergence and spread is accelerated by human activity or caused by non-completion or non-recommended use of antimicrobials to treat, prevent or control infections in humans, animals and plants.

Please note: In this course the term ‘misuse’ of antibiotics, which puts blame on individuals, has been avoided. This course hopes to demonstrate that non-completion or non-recommended use of antibiotics is largely due to harmful power structures that affect the decisions that individuals can make when accessing treatment for themselves or their animals.

Socioeconomic challenges and inequities affect people’s experience of AMR, from exposure to infection to diagnosis and treatment. This is illustrated in Table 2, which shows the World Health Organization’s (WHO) people-centred approach to addressing AMR in human health (WHO, 2023). A focus on the social determinants of health is important because it enables an understanding of the AMR-specific health challenges that people face.

Many of these social challenges are equally relevant to animal health, for example in how they affect access to vaccines for animals and animal health worker training on AMR.

| Challenge | System challenges | People’s challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention of infection |

|

|

| Access to health services |

|

|

| Diagnosis |

|

|

| Treatment |

|

|

Footnotes

Infection prevention is important in both communities and healthcare facilities and continues throughout the journey. Treatment includes the continuous care that might be required for an AMR infection. The list of challenges may not be exhaustive or applicable to all countries. OTC = over-the-counter; IPC = infection, prevention and control.The impact of the inequities illustrated in Table 2 can be seen in the global inequitable burden of AMR. Up to 90% of deaths from AMR occur in the Global South (Mendelson et al., 2024). These contexts often experience high rates of infectious disease, challenges in access to healthcare and global inequities relating to the supply of vaccines and antimicrobials.

For example, in sub-Saharan Africa nearly 1 in 1000 deaths are already associated with bacterial AMR, compared with only half as many in high-income countries (Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, 2022). Within countries, the AMR burden is also unequally distributed – but there is no detailed data on how due to the absence of analysis of AMR data disaggregated by gender and other equity-related factors at a national level.

You can learn more about the burden of AMR and how it is measured in the course The health and economic burden of AMR.

5 AMR, sex and gender

Sex differences and gender norms both drive and shape AMR. The following two sections unpack this further.

5.1 AMR and sex differences

Sex – the biological differences between males, females and intersex people – can shape susceptibility to infection, including resistant infections (Figure 4). For example, females have a higher risk of developing UTIs because they have a shorter urethra, and UTIs have a high drug-resistance potential (Gautron et al., 2023). Risk of infection also increases around menstruation and pregnancy, which highlights how physiological changes over the life course have implications for exposure and vulnerability (Ghouri and Hollywood, 2020).

Biological or sex factors also interact with diverse social factors, including those that relate to gender:

- Healthcare settings can be sites of high exposure to resistant infections, and women often spend significant amounts of time there. This is in part due to sex-related factors such as childbirth but it is also because of common gender norms around women’s role as caregivers.

- Malnutrition can increase susceptibility to infection, including resistant infection. This is also gendered because in many contexts, families experiencing food insecurity may prioritise feeding boy children because of their economic roles.

- Poor water, sanitation and waste management can create conditions that drive the spread of infection, including resistant infections. Women and girls may be particularly affected by this because of the intersection of anatomical factors and their particular exposure to water-borne infections due to their role collecting water for the household (Gautron et al., 2023).

5.2 AMR and gender differences

The specific ways that people are exposed to antimicrobials and resistant infections, experience AMR, and have knowledge of AMR are significantly influenced by biology, gender and other intersectional inequities.

Susceptibility : Biological susceptibility is affected by malnutrition, co-morbidities and exposure to pollutants and occupational hazards (e.g. mining). For example, high levels of HIV infection among young women in Nigeria increase their biological susceptibility to drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB). These high levels of HIV infection are thought to be due to intergenerational relationships where young women marry older men who are more likely to be living with HIV (Oladimeji et al., 2023).Exposure : Exposure to resistant infections can be influenced by gender norms and roles. Frontline health workers are predominantly women (O'Donnell et al., 2010) and consequently they have high exposure to resistant infections (Gautron et al., 2023). Sex workers have a high risk of exposure to resistant sexually transmitted infections and limited ability to negotiate for safer sex with clients (WHO, 2012; Deering et al., 2013). Lack of access to adequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) systems can create environments in which people experience high exposure to resistant infections (Cocker et al., 2023). Research suggests that women are more likely to be prescribed antimicrobials than men (Schröder et al., 2016).- Access to health services, treatment and continuity: Low-income communities and particularly female-headed households may not have finances to access formal health services or to ensure continuation of antimicrobial treatment for HIV infection or TB, which both require long-term courses of medication (Shembo et al., 2022). This can also intersect with issues of food insecurity because some medications are to be taken on a full stomach (Kiekens et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2022).

- Health-seeking autonomy: Household power relations can affect health-seeking autonomy. In many patriarchal settings, men or older women have decision-making power over younger women and girls. For example, among pastoralist communities in Tanzania, boys’ health may be prioritised because of their herding duties; girls and women may have to seek the permission of men to seek healthcare (Barasa and Virhia, 2022).

- Impacts: Catastrophic costs associated with healthcare can hit people already living in poverty hardest. People with multi-drug-resistant TB may have to take multiple, long-term treatments that can reduce their ability to work and push them further into poverty (Kaswa et al., 2021). Stigma relating to resistant infections can also be gendered: one study found that UTIs were thought of as illnesses resulting from poor hygiene, which prevented women in particular from seeking early care (Barasa et al., 2022).

Optionally, if you are interested in exploring this area further, you may be interested in reading ReAct’s report Scoping the Significance of Gender for Antibiotic Resistance report by the ReAct group.

Now try Activity 5, which illustrates how SDHs shape susceptibility and exposure to, and the treatment of, AMR.

Activity 5: Rani’s story

The following scenario has been developed to illustrate how gender and other inequities shape susceptibility and exposure to, and the treatment of, AMR through the life course of Rani. Rani is a fictional character, but her experience is based on reality.

As you read through the scenario, think about the specific ways in which gender inequality impacted Rani's health and access to healthcare throughout her life. Reflect and take notes on the following:

- How did various environmental factors increase Rani’s risk of infection?

- How did the roles she held in her family and community contribute to these exposures?

Infancy: Rani’s life began in a small village in rural Maharashtra, India. She experienced poor living conditions, food insecurity and lack of clean drinking water as an infant and so was malnourished with a weakened immune system. Her brothers always seemed to get the larger portions, leaving Rani hungry. Her childhood was spent fetching water from the village well, a daily chore that exposed her to contaminated water sources. The inadequate sanitation system meant that resistant infections spread frequently and widely, particularly among the girls in her community.

Adolescence: When Rani became a teenager, the burden of domestic labour fell heavily upon her shoulders. She spent hours cooking over smoky chulhas [stoves], the acrid smoke stinging her eyes and lungs, making her prone to pneumonia. Handling uncooked food, she was constantly exposed to bacteria.

Her menstrual cycles brought another layer of vulnerability, and she contracted recurring UTIs and reproductive tract infections (RTIs). Information about proper hygiene and antibiotic use was scarce. Household elders had decision-making authority to decide when and where to seek healthcare; Rani was not involved in making these choices.

Adulthood: After getting married, Rani fell pregnant and suffered from a UTI. Her husband purchased a medication from a local informal pharmacy without diagnosis. Rani, needing permission from her mother-in-law to seek medical help, often delayed treatment.

Rani wanted to provide for her new family so started working as a waste picker on the fringes of an informal settlement next to an industrial area, where the air was thick with smoke. She collected plastic bottles, caps, boxes and metals to sell on to scrap dealers, with no personal protection. She carried heavy loads in the heat of the day and was physically exhausted and dehydrated. She woke before light to do this work and was worried for her safety. Women she worked with were sometimes victims of sexual gender-based violence, exposing them to sexually transmitted infections.

Rani also kept chickens. The agricultural extension programmes, dominated by men, rarely targeted women like Rani, leaving her uninformed about safe farming practices.

Older life: As she aged, menopause brought hormonal shifts that made her susceptible to infections. Rani didn’t have many friends or family to talk to and lacked access to medical help. Limited access to social networks and health facilities meant she was isolated, lacking vital information about AMR and appropriate antibiotic use. She became the primary caregiver for her grandchildren and relatives.

One day, Rani developed a persistent cough and fever. The antibiotics she bought from a local pharmacist were ineffective, but she did not have the money to pay for diagnostic testing. Rani succumbed to an untreatable infection.

Discussion

Hopefully this case study has illustrated to you the ways in which gender, poverty and other inequitable power structures can drive AMR. You may have noted some of the following:

- Gender preferences for boy children may have led to malnutrition for Rani. This can increase susceptibility to infections, including resistant infections.

- Gender roles within the family meant domestic tasks such as cooking and caregiving were given to Rani, which increased her exposure to infections.

- Gendered power structures in both the family and society meant that Rani had limited access to or information about healthcare.

- Power structures also meant that Rani was exposed to infections (including resistant infections) through her work as a waste picker. These environments can also stress the environmental microbiome, furthering resistance.

- Biological factors also intersected with gendered norms in terms of Rani’s susceptibility to drug-resistant infections.

While gender differences in AMR highlight disparities in exposure, access and care-seeking behaviours, revisiting the broader social and structural drivers explores how these gendered inequities are both shaped by and reinforce systemic AMR risks.

6 Revisiting the social and structural drivers of AMR

As you will have come to understand from your study in the course so far, AMR drivers are about not only antimicrobial practices but also social and structural determinants of health: the underlying societal and environmental factors that create conditions conducive to the development and spread of AMR.

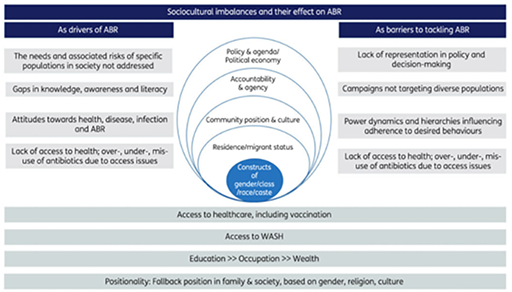

These are explained in Figure 5, which highlights how drivers of antibiotic resistance and barriers to managing antibiotic resistance are shaped by the socio-cultural inequities (such as gender inequity) that exist at multiple levels – from community to national and international. This includes stigma and social norms within communities, but also power structures within national health system structures and the lack of representation of communities and diverse groups in political decision-making. In this way, managing the spread of AMR needs to look beyond people’s knowledge and behaviours.

-

Think back to Table 2, which illustrates the challenges faced on the AMR people journey. Can you see how the sociocultural imbalances illustrated in Figure 5 map onto the AMR journey?

-

Things to consider here include:

- decision-making norms about access to healthcare, such as autonomy in decision-making

- access to education and knowledge about AMR

- the economic costs of diagnostic testing and the availability of diagnostic testing in countries.

Figure 5 highlights that AMR is not an issue of ‘misuse’, but rather of the structures that prevent recommended use. In fact, bans on antibiotic use are often offered as solutions to curb AMR. However, evidence from Mexico shows that these bans do not work, and people will find ways to work around them (Pérez-Cuevas et al., 2014). This is largely because in many contexts, there is an absence of holistic healthcare and antibiotics are seen as a ‘quick fix’ for the systemic disparities in power, resources and opportunities that result from institutionalised biases and practices (Willis and Chandler, 2019). Context, therefore, is critically important; this will be illustrated in the following case study on urban informal settlements.

6.1 A case study on urban informal settlements

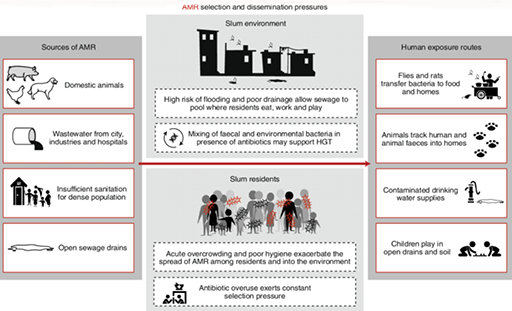

Urban informal settlements comprise a key structural inequity and have been described as hotspots for AMR (Nadimpalli et al., 2020). They are a clear case study of why structural inequities drive AMR.

Informal settlements are often deemed to be ‘illegal’ because of an absence of formal governance, leading to poor environmental conditions, a lack of adequate healthcare and, subsequently, a proliferation of informal antibiotic use. Figure 6 illustrates how these conditions can facilitate the spread of AMR and constrain peoples’ abilities to access and use antimicrobials in the recommended ways.

Now complete Activity 6, which considers a case study of AMR in urban informal settlements.

Activity 6: A case study of AMR in urban informal settlements

Read the following case study on AMR in urban informal settings and watch the first five minutes of Video 3. Then answer the questions that follow.

Antibiotics as a quick fix for hygiene and inequality

Grace brings us into her house to show us her plastic basket of medicines she keeps on hand at home. It is a small collection of Panadol (paracetamol), some amoxicillin tablets and a full box of metronidazole. She explains that the metronidazole is an absolute necessity here in this urban informal settlement in downtown Kampala, Uganda, where chronic diarrhoea – and the serious abdominal pain associated with it – is a condition that many adults and children live with every day.

Walking through the settlement with her we pass the few existing fee-for-use latrines in the community, but Grace explains that most cannot afford them, and that regardless, many avoid them because they are so unclean. She explains that many people – including her – simply use home bucket systems or polythene bags for toileting, and then dispose of their waste either in the open drainage channels that run through the settlement or in community rubbish piles. These are the same drainage channels where people must wash their clothes and collect water for their livestock and gardens.

Further exacerbating this situation, the settlement is built on and beside a wetland area, and these drainage channels often flash-flood during the rainy season, with waters rising to knee-height and circulating inside people’s homes, their livestock pens and their small gardens. Here, antibiotics are put to use to make unavoidable diarrhoeal disease bearable, enabling people to carry on with their work and family commitments despite chronic diarrhoea and abdominal pain.

There is little political will to tackle these issues, as the local press describes the informal settlement as a problematic ‘slum’, while the people who live there are cast as ‘illegal squatters’ and criminals. Here, antibiotics provide a quick fix for wider structural and political issues, manifested as a lack of hygiene in contexts of poverty.

- In what ways do structural inequities drive AMR in informal settlements, or in a similar context that you might be familiar with?

- How are exposure and susceptibility shaped through the different types of environmental factors in urban informal settlements?

Discussion

Poor housing, water and sanitation systems lead to high levels of infections, including resistant infections. Poverty in informal settlements reduces people’s access to timely and equitable health services, meaning that people are more likely to need to access antimicrobials informally and use them regularly to address recurrent infections.

An intersectional approach helps to show how gender inequality and other overlapping factors like poverty or race amplify health risks faced by those living in informal settlements. Combining this with a One Health approach can highlight the intersections of human, animal and environmental health, and how these are inequitable.

7 One Health, gender and intersectionality

There is therefore significant overlap between One Health and intersectionality theory, which emphasises how different SDHs and power relations overlap and intersect to create specific experiences. Both One Health and intersectionality highlight how the combination of various factors experienced at individual and group levels is influenced by societal processes and structures of power (Davis et al., 2025 [forthcoming]).

Using an intersectional lens to study AMR is critical to understanding how individuals experiencing multiple forms of marginalisation may face heightened vulnerability. This includes thinking about how people’s physical and social locations shape their vulnerability, susceptibility and experiences of AMR, and how these overlap with other contextual issues such as climate change and conflict.

This course takes a primarily human-centred lens, but there are many ways in which power structures and harmful gender norms intersect with animal health and environmental health. These concepts are explored more in Video 4 from the Just Transition initiative.

7.1 Gender inequities in animal health

The pathways of antimicrobial exposure, the burden of resistant infections and the comprehension of AMR within animal health systems are significantly gendered. This results in distinct experiences for different genders across the animal health sector.

Women farmers may face significant hurdles in accessing vital livestock services. Research in Kenya found that livestock service providers held negative attitudes towards women farmers that meant that, despite women acknowledging the benefits of livestock vaccination, they were less likely to use vaccines due to sexist perceptions and economic gender inequalities (Kyotos et al., 2022).

A study of rural female smallholder farmers in Rwanda and Uganda found that women preferred to care for chickens and goats rather than cattle (Mutua et al., 2019; Mukamana et al., 2022). However, because government vaccination programmes often focus on vaccinating larger livestock for diseases such as Rift Valley fever (Acosta et al., 2022; Mukamana et al., 2022; Tukahirwa et al., 2023), these programmes – which often subsidise cost and remove physical barriers to vaccinations – are less available to women.

Other research found that women had to seek permission from their husbands before purchasing vaccines or accessing resources in general (Mukamana et al., 2022). Additionally, women may lack the required transportation to travel to vaccination places, and doing so may involve a higher personal risk for women than for men farmers due to gender-based violence (Enahoro et al., 2021; Acosta et al., 2022). Despite this, women were active in self-help groups that aided raising funds and providing physical labour and improved their access to livestock vaccinations (Jumba et al., 2020).

In many societies, including pastoralist communities, men may be more likely to carry out animal slaughter work, which brings significant risk of exposure to resistant infections (Barasa, 2019).

Having explored gender and inequity in AMR drivers, you are now going to look at how data disaggregation in AMR surveillance systems has value in understanding inequitable trends in AMR.

8 AMR surveillance and equity

When you can’t see a problem, you pretty much can’t solve it.

Currently, efforts are being made to strengthen global AMR surveillance data. This is wonderful, and gives a picture of the general burden of disease among populations. But given what you now know about gender and intersectional inequities driving AMR, do you think it’s important to know who is affected by AMR? You’ll explore the need for disaggregated data in the next section.

8.1 The need for disaggregated data

Much of the surveillance data collected about resistant infections at a global level, for example in the WHO’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) is

Disaggregated data supports AMR capacity-strengthening in countries because it provides context-specific understandings of burden of disease. Some countries already have data disaggregated by sex and age, and GLASS now lets you report in this way. It is critical that all countries start reporting disaggregated data to allow for an understanding of the burden of resistant infections within countries to understand which groups are most at risk or affected.

Activity 7: AMR surveillance and equity

Read the GEAR up report on including intersectional indicators within AMR surveillance (GEAR up, 2024a).

As you read the report, note down whether any of these indicator suggestions are surprising to you – and if so, why?

Discussion

A truly intersectional approach requires a diverse set of equity variables and indicators. National action plans (NAPs) and surveillance systems are increasingly moving to include equity variables in surveillance data collection, but there is still a long way to go.

8.2 Limits to surveillance data

Equitable AMR surveillance depends on comprehensive data, but persistent limits in surveillance systems often exclude the marginalised communities most affected by AMR. It is also important to consider the limitations of surveillance data and what it currently cannot tell us, including biases in the data that need to be understood.

AMR surveillance also relies primarily on data collected at health facilities. This means that community-level infections are rarely detected, particularly among those who use informal health providers. Additionally, individuals and groups who face specific barriers to accessing formal health services and diagnostics will not be represented in surveillance data.

This highlights the fact that trends in surveillance data cannot be understood without the contextual understandings of the upstream drivers of exposure, health-seeking, use of antimicrobials and animal health, which can be unpacked with qualitative and social science research.

Together, surveillance data and contextual social research can support decision-making and intervention design. Surveillance data needs to be complemented with:

- research to map the burden of resistance among communities and key populations that may be excluded from current surveillance efforts

- qualitative or co-produced research with communities that unpacks structural drivers of AMR and prioritises community knowledge to support context-appropriate intervention design and prevention.

To mitigate these barriers, it’s important to address the equity gaps in AMR.

9 Addressing equity in AMR

Given the significance of inequities (including gender inequity) in AMR and One Health, there is a need to address these inequities in AMR research and interventions. The following extract explores some reasons why gender and equity considerations are important in AMR research.

Why are gender and equity considerations important in AMR research?

- Household and community settings: Gender inequalities reduce women’s power in household financial and healthcare decisions, limiting their treatment choices and fostering practices like antibiotic sharing.

- Effective community-level AMR interventions must address interlinkages between gender dynamics and other inequalities.

- Healthcare settings: Women are over-represented in frontline healthcare, facing heightened drug-resistant organism exposure. Limited access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities escalates risks.

- Recognising these overlapping gendered vulnerabilities informs appropriately targeted AMR interventions.

- Agriculture settings: Women in agriculture are predominantly smallholder farmers and struggle to afford livestock vaccines. This leads to livestock infections, harming women’s livelihoods and increasing antimicrobial reliance.

- A gender-focused approach in research helps curb the deepening of existing inequalities.

In Activity 8 you will consider gender and equity data in your own context.

Activity 8: Gender and equity data in your own context

9.1 Incorporating gender considerations into AMR research and interventions

In 2024 the WHO’s National Action Plans and Monitoring and Evaluation team identified several recommendations for addressing equities in AMR. These recommendations are summarised below. Highlights include the need for:

- multisectoral action and coordination that can cut across One Health domains as well as governance of areas such as water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), housing, health systems and transport

- data disaggregated by key equity indicators, including sex, age, geographic location (at minimum), and ideally other social stratifiers such as (but not limited to) socioeconomic status, ethnicity, refugee status and disability

- incorporation of equity considerations into AMR national action plans (NAPs) and into multisectoral AMR coordination

- (in the longer term) improved access to WASH and essential health services, with the goal of preventing resistant infections in the first place.

Summary of AMR and gender recommendations

Overarching

- Short term. Capture and disaggregate data on AMR and surveillance of antimicrobial use and other relevant data by, at minimum, sex and age and, where feasible, other social stratifiers.

- Short term. Review existing national plans or strategies in the health sector or other relevant areas and incorporate policies or actions that strive for gender equality into the NAP on AMR.

- Medium term. Promote research to strengthen the evidence base on the intersections between gender and AMR.

Effective governance, awareness and education

- Short term. Promote equal participation of women, men and other vulnerable groups and/or groups facing discrimination in the multisectoral AMR coordination mechanism and technical working groups.

- Short term. Include representation from gender experts in the multisectoral AMR coordination mechanism.

- Short term. Use context-specific messages, language and images in AMR awareness and education materials that actively address harmful gender norms and promote gender equality.

- Short term. Use different and tailored approaches to raise awareness [of] AMR among vulnerable groups and/or groups facing discrimination.

- Medium term. Strengthen the knowledge of health workers at all levels of healthcare on gender inequalities in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of (drug-resistant) infections.

Strategic information through surveillance and research

- Short term. Report on patients’ sex, age and, where feasible, other social stratifiers as part of routine surveillance systems on AMR and antimicrobial use.

- Medium term. Analyse, report and act upon the key gender-related inequalities identified from sex-disaggregated surveillance data on AMR and antimicrobial use.

- Long term. Invest in new diagnostics for infections that disproportionally affect women such as (drug-resistant) urinary tract infections.

Prevention

- Medium term. Improve WASH and waste management infrastructure in health facilities and community settings to ensure infrastructure is available, accessible and safe for all genders, and does not perpetuate stigma and discrimination.

- Medium term. Identify and address gender inequalities in the risk of exposure to (drug-resistant) infections among healthcare workers and in community settings. On vaccination, evidence supports the set of recommendations in the WHO Immunization Agenda 2030: Why Gender Matters (2021) report of gender mainstreaming across the entire immunisation programme cycle.

Access to essential health services

- Medium term. Deliver culturally sensitive and gender-responsive health services for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of (drug-resistant) infections.

- Medium term. Ensure health insurance and/or health benefit packages cover access to health services, diagnostics and antimicrobials for the treatment of (drug-resistant) infections without leaving behind vulnerable populations.

- Short term. Identify and address gender inequalities in access to quality-assured medicines including antimicrobials, focusing on specific groups of women or men who might be at a higher risk of purchasing substandard or falsified antimicrobials.

- Medium term. Update and implement standards on the forecasting and procurement of medicines including antimicrobials by undertaking an assessment of the local epidemiology of infections based on sex to ensure all relevant antimicrobials are included.

Timely, accurate diagnosis

- Long term. Conduct retrospective reviews of diagnostic services for different (drug-resistant) infections to identify and address any gender inequalities.

Appropriate, quality-assured treatment

- Medium term. Apply a gender analysis in regular retrospective prescription audits to identify unconscious gender biases or inequalities in prescribing practices.

- Medium term. Conduct a gender assessment of the unintended effect of policies or regulations that aim to reduce over-the-counter [sales] of antimicrobials on access to essential antimicrobials.

9.2 The importance of community engagement in intervention design

As you have seen, AMR surveillance prioritises specific forms of quantitative data, often collected at tertiary health facilities, over qualitative community-level data and perspectives.

Recognising the significance of gender and other intersectional inequities in shaping differential behaviours and outcomes related to AMR, community engagement can serve as a key approach to address the social drivers. It follows the principle of equitable partnership fostering collaboration with communities to co-design interventions or solutions that are contextually relevant, inclusive and just.

Community engagement approaches to research (e.g. participatory video-making and community dialogue approaches [CDA]) centre community voices – particularly those of marginalised and underrepresented groups – to inform decision-making. CDA was applied by HERD International in Nepal as part of the COSTAR project to address the social drivers of AMR and associated behaviours at the community level, with a focus on gender, power relations and other equity indicators. CDA is a community-driven approach that aims to empower communities to identify and implement sustainable and contextual solutions for health. This informed the creation of flipbooks designed to share context-relevant understandings of AMR and recommended use of antibiotics. They were tailored to age, literacy and sociocultural norms. Pictures were created with community input and designed to be inclusive of gender identities. Facilitators from local communities conducted CDA discussions in rural settings, in which community participants discussed their issues, explored challenges, identified solutions and planned action that is relevant to their individual and societal context.

Next you will explore how these equity issues can be addressed in country AMR national action plans (NAPs).

9.3 Equity in national action plans

There needs to be a gender and equity focus in all efforts to protect and improve population health, as acknowledged in global mandates such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN, n.d. 1) and the UN Women Strategic Plan 2022–2025 (UN, n.d. 2).

Containing and controlling AMR demands coordinated, international action across a broad range of sectors. Within individual countries, governments will need to work with multiple stakeholders, across diverse sectors and disciplines, to tackle AMR. At the very minimum, that means multisectoral collaboration across health and agriculture. More often, it also means coordinating action with departments of trade, finance and the environment, among others. Deliberate coordination and collaboration between key stakeholder groups, such as government, civil society and the private sector, is also needed.

A 2024 WHO review of 145 NAPs for AMR found that 125 of 145 publicly available NAPs did not include mentions of sex or gender. Policy and interventions that do not address inequities risk exacerbating equity challenges (WHO, 2020). NAPs are an important entry point to consider and strengthen the gender and equity responsiveness of national efforts to tackle AMR.

Figure 9 illustrates how addressing equity in AMR NAPs can lead to reduction in mortality and morbidity due to drug-resistant infections.

Examples of good practice come from Uganda and Malawi’s NAPs, both of which mainstream gender considerations.

Mainstreaming gender considerations in Uganda’s NAP

GEAR up is a global consortium that seeks to catalyse action on gender and equity in AMR through supporting Fleming Fund country grantees to mainstream gender and equity within routine AMR systems and structures. GEAR up supported the mainstreaming of Uganda’s 2024–2028 NAP. Key steps in the process were:

- Supporting capacity on gender, equity and intersectionality through a participatory workshop with key stakeholders:

- Participants explored how social determinants intersect to influence susceptibility to drug-resistant infections, health-seeking behaviours and antimicrobial consumption. This underscored the need for AMR surveillance to evolve beyond a focus on ‘bugs and drugs’ toward equitable practices grounded in effective governance, multisectoral collaboration and evidence-based strategies.

- The workshop introduced participants to the concept of intersectionality, providing insights into how overlapping factors shape vulnerabilities to AMR risks. By recognising the varied risks faced by different populations, this approach ensures that AMR interventions do not inadvertently create inequities. Participants discussed practical applications, paving the way for solutions that promote gender equality and address social determinants in AMR strategies.

- A collaborative review process to strengthen Uganda’s AMR Action Plans and surveillance tools:

- Stakeholders examined key national documents and identified gaps and proposed actionable recommendations to enhance inclusivity and responsiveness, including the need for data disaggregated beyond sex and age, and incorporating variables such as education level, marital status and disability.

- Fostering a collaboration for inclusive AMR programming:

- Discussions emphasised the importance of multisectoral partnerships among the Ministry of Health, private sector actors and implementing partners to ensure sustained, inclusive AMR programming. These collaborations aim to create shared accountability and collective action in addressing AMR challenges across sectors.

- Drafting a framework for gender and equity integration:

- The development of a draft terms of reference for a gender and equity focal team to serve a guiding body to ensure that gender and equity considerations are systematically integrated into Uganda’s AMR programming. This reflects a long-term commitment to inclusivity and sustainability.

You can read more about this process in the full GEAR up blog (GEAR up, 2024b).

Now complete Activity 9 to consider the NAP for AMR in your country.

Activity 9: Equity in NAPs

Find your country’s NAP for AMR in the WHO library of AMR NAPs.

If a NAP for your country is not available, select one for a country of interest. To get the most out of this activity we suggest that you select a NAP for a country that is in a similar region to your own.

Using the situational analysis in the NAP, identify whether:

- any differences between males and females are discussed

- any vulnerable groups are discussed

- any information is available for differences between other groups – for example, age groups, geographical locations, educational levels, occupations or workplace settings.

Discussion

Depending on where you live and which NAP you looked at, you may have seen that the situational analysis in your NAP included data on the differences between groups. If you did not find any data on differences between groups does the NAP include any plans to collect disaggregated data? Or do you know when the NAP is due for renewal?

Many NAPs are still ‘gender-blind’ in that they do not distinguish between men and women; however, progress is being made towards more gender-sensitive NAPs. If you want to see an example of a gender mainstreamed NAP you should look at Malawi’s or Uganda’s.

Now you will move on to reflect on how you can take your learning from this course in your work for positive action.

10 Gender and equity in your work

Gender equity is everyone’s responsibility and everyone’s gain. Achieving it will require a collective approach, with a role for everyone. All the small actions that are taken by individuals and organisations will be important.

Before you finish this course this final activity will help you to think about how what you have learned relates to your role.

Activity 10: Gender and equity in your work

Think about what you have learned in this course and then reflect and make notes in response to the following questions:

- Does your institution or organisation have a commitment to gender equity?

- Does your country have specific gender equity mandates or policies at a national level?

- How might you embed gender equity in your practice in AMR?

11 End-of-course quiz

Well done – you have reached the end of this course and can now do the quiz to test your learning.

This quiz is an opportunity for you to reflect on what you have learned rather than a test, and you can revisit it as many times as you like.

Open the quiz in a new tab or window by holding down ‘Ctrl’ (or ‘Cmd’ on a Mac) when you click on the link.

12 Summary

In this course you have learned how social and structural inequities come together with biological factors and processes to create a complex picture that shapes and drives AMR risks and disease burden. You have explored the limitations in surveillance data and explored practical steps to move towards more inclusive and representative data and policy making for AMR.

You should now be able to:

- define key terms and concepts related to gender and equity in AMR

- explain how biological factors, including sex, contribute to differences in the effects of AMR

- explain how gender roles, social norms and social determinants influence AMR exposure and experience across different life stages, identifying which social groups may be differently at risk of or impacted by AMR, and how this aligns with key gender equity and human rights mandates

- outline how focusing on equity can strengthen the One Health approach to AMR

- describe the current biases and inequities in AMR data, and explain the importance of disaggregated data in understanding AMR trends across human health, animal health and the environment

- make recommendations for more equitable approaches to AMR interventions and surveillance

- reflect on how gender-responsive and equitable practices in AMR relate to your work.

Now that you have completed this course, consider the following questions:

- What is the single most important lesson that you have taken away from this course?

- How relevant is it to your work?

- Can you suggest ways in which this new knowledge can benefit your practice?

When you have reflected on these, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

Activity 11: Reflecting on your progress

Do you remember at the beginning of this course you were asked to take a moment to think about these learning outcomes and how confident you felt about your knowledge and skills in these areas?

Now that you have completed this course, take some time to reflect on your progress and use the interactive tool to rate your confidence in these areas using the following scale:

- 5 Very confident

- 4 Confident

- 3 Neither confident nor not confident

- 2 Not very confident

- 1 Not at all confident

Try to use the full range of ratings shown above to rate yourself:

When you have reflected on your answers and your progress on this course, go to your reflective blog and note down your thoughts.

13 Your experience of this course

You’ve now reached the end of this course. If you’ve enrolled on a pathway, please go back to the pathway page and tick the box to confirm that you’ve completed this course. On the pathway page you’ll see both your progress so far as well as the other courses you need to complete in order to achieve your Certificate of Completion for that pathway.

Now that you have completed this course, take a few moments to reflect on your experience of working through it. Please complete a survey to tell us about your reflections. Your responses will allow us to gauge how useful you have found this course and how effectively you have engaged with the content. We will also use your feedback on this pathway to better inform the design of future online experiences for our learners.

Many thanks for your help.

Further reading and resources

If you are interested in finding out more about some of the areas covered in this course you may like to read some of the following resources:

- More about the social determinants of health: Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T. and Taylor, S. (2008) ‘Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health’, The Lancet, 372(9650), pp.1661–9 [online]. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/ journals/ lancet/ article/ PIIS0140-6736(08)61690-6/ abstract (accessed 6 June 2025).

- Using the social determinants of health to design equitable policies for health: Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M. (1991) Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health: Background Document to WHO – Strategy Paper for Europe, Institute for Future Studies [online]. Available at: https://www.iffs.se/ publikationer/ arbetsrapporter/ policies-and-strategies-to-promote-social-equity-in-health/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

- Integrating equity considerations into research and intervention design for AMR: Lynch, I., Middleton, L., Naemiratch, B., Fluks, L. and Sobane, K. (2023) Practical Pathways to Integrating Gender and Equity Considerations in Antimicrobial Resistance Research, ICARS/IDRC [online]. Available at: https://icars-global.org/ knowledge/ practical-pathways-integrating-gender-and-equity-considerations-in-antimicrobial-resistance-research/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

References

Acosta, D., Ludgate, N., McKune, S.L. and Russo, S. (2022) ‘Who has access to livestock vaccines? Using the social-ecological model and intersectionality frameworks to identify the social barriers to peste des petits ruminants vaccines in Karamoja, Uganda’, Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9, 831752.

ALIGN (n.d.) ‘About norms’ [online]. Available at https://www.alignplatform.org/ about-norms (accessed 6 June 2025).

American Public Health Association [YouTube user] (2016) ‘Michael Marmot and the social determinants of health’, YouTube, 1 November [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=BHYBHKma3x8 (accessed 5 June 2025).

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators (2022) ‘Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis’, The Lancet, 399(10325), pp. 629–55.

Barasa, V. (2019) ‘WaArusha agro-pastoralist experiences with risk of febrile illness: an ethnographic study of social drivers of zoonoses and rural health-seeking behaviours in Monduli district, Northern Tanzania’, DPhil dissertation, University of Sussex, 23 October [online]. Available at: https://sussex.figshare.com/ articles/ thesis/ WaArusha_agro-pastoralist_experiences_with_risk_of_febrile_illness_an_ethnographic_study_of_social_drivers_of_zoonoses_and_rural_health-seeking_behaviours_in_Monduli_district_Northern_Tanzania/ 23472545?file=41180963 (accessed 5 June 2025).

Barasa, V. and Virhia, J. (2022) ‘Using intersectionality to identify gendered barriers to health-seeking for febrile illness in agro-pastoralist settings in Tanzania’, Frontiers in Global Women's Health, 2, 746402.

Charani, E., Mendelson, M., Ashiru-Oredope, D., Hutchinson, E., Kaur, M., McKee, M., Mpundu, M., Price, J. R., Shafiq, N. and Holmes, A. (2021) ‘Navigating sociocultural disparities in relation to infection and antibiotic resistance – the need for an intersectional approach’, JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance, 3(4), dlab123.

Cocker, D., Sammarro, M., Chidziwisano, K., Elviss, N., Jacob, S.T., Kajumbula, H., Mugisha, L., Musoke, D., Musicha, P., Roberts, A.P. and Rowlingson, B. (2023) ‘Drivers of resistance in Uganda and Malawi (DRUM): a protocol for the evaluation of one-health drivers of extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) resistance in low-middle income countries (LMICs)’, Wellcome Open Research, 7, p. 55.

Collins, T. (2023) ‘Putting gender and equity at the heart of the Fleming Fund’s next phase’, programme update, 24 March [online]. Available at: https://www.flemingfund.org/ publications/ putting-gender-and-equity-at-the-heart-of-the-fleming-funds-next-phase/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

Crenshaw, K. (2013) ‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’, in Maschke, K. (ed.) Feminist Legal Theories, pp. 23–51, New York, NY: Routledge.

Dahlgren, G. and Whitehead, M. (1991) Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health: Background Document to WHO – Strategy Paper for Europe, Institute for Future Studies [online]. Available at: https://www.iffs.se/ publikationer/ arbetsrapporter/ policies-and-strategies-to-promote-social-equity-in-health/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

Davis et al. (2025) [forthcoming].

Davis, K., Mavhu, W. and Steege, R. (2024) What’s gender got to do with it? Results from the GEAR up consortium systematic review on gender and equity in AMR in LMICs, research poster on behalf of the GEAR up Consortium [online]. Available at: https://gearupaction.org/ tools-and-resources/ poster-whats-gender-got-to-do-with-it/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

Deering, K.N., Lyons, T., Feng, C.X., Nosyk, B., Strathdee, S.A., Montaner, J.S. and Shannon, K. (2013) ‘Client demands for unsafe sex: the socioeconomic risk environment for HIV among street and off-street sex workers’, Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63(4), pp. 522–31.

Dias, S.P., Brouwer, M.C. and van de Beek, D. (2022) ‘Sex and gender differences in bacterial infections’, Infection and Immunity, 90(10), pp. e00283-22.

Enahoro, D., Galiè, A., Abukari, Y., Chiwanga, G.H., Kelly, T.R., Kahamba, J., Massawe, F.A., Mapunda, F., Jumba, H., Weber, C., Dione, M., Kayang, B. and Ouma, E. (2021) ‘Strategies to upgrade animal health delivery in village poultry systems: perspectives of stakeholders from northern Ghana and central zones in Tanzania’, Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 611357.

Gautron, J.M., Tu Thanh, G., Barasa, V. and Voltolina, G. (2023) ‘Using intersectionality to study gender and antimicrobial resistance in low-and middle-income countries’, Health Policy and Planning, 38(9), pp. 1017–32.

GEAR up (2024a) ‘Including intersectional indicators within AMR surveillance’, 8 October [online]. Available at: https://gearupaction.org/ tools-and-resources/ draft-including-intersectional-indicators-within-amr-surveillance/ (accessed 5 June 2025).

GEAR up (2024b) ‘Moving beyond bugs and drugs: Integrating gender and equity in AMR programmes in Uganda’, 13 December [online]. Available at: https://gearupaction.org/moving-beyond-bugs-and-drugs-integrating-gender-and-equity-in-amr-programmes-in-uganda/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

Ghouri, F. and Hollywood, A. (2020) ‘Antibiotic prescribing in primary care for urinary tract infections (UTIs) in pregnancy: an audit study’, Medical Sciences, 8, pp. 40–49.

Global Health 5050 (n.d.) ‘Why gender and health?’ [online]. Available at: https://global5050.org/ gender-and-health/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

Hankivsky, O., Cormier, R. and De Merich, D.I. (2009) Moving Women’s Health Research and Policy Forward. Vancouver: Women’s Health Research Network.

Harper, C., Khan, A., Browne, E. and Michalko, J. (2025) ‘There’s not enough money – so why spend it on gender equality and justice?’, expert comment, ODI Global, 14 March [online]. Available at: https://odi.org/ en/ insights/ theres-not-enough-money-so-why-spend-it-on-gender-equality-and-justice/ (accessed 6 August 2025).

International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) (2024) ‘With Trump’s election, global reproductive justice is at risk, and health services threatened across continents’, 8 November [online]. Available at: https://www.ippf.org/ media-center/ trumps-election-global-reproductive-justice-risk-and-health-services-threatened-across (accessed 6 June 2025).

Jumba, H., Teufel, N., Baltenweck, I., de Haan, N., Kiara, H., and Owuor, G. (2020) ‘Use of the infection and treatment method in the control of East Coast fever in Kenya: does gender matter for adoption and impact?’, Gender, Technology and Development, 24(3), pp. 297–313.

Kaswa, M., Minga, G., Nkiere, N., Mingiedi, B., Eloko, G., Nguhiu, P. and Garcia Baena, I. (2021) ‘The economic burden of TB-affected households in DR Congo’, The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 25(11), pp. 923–32.

Kiekens, A., Mosha, I.H., Zlatić, L., Bwire, G.M., Mangara, A., Dierckx de Casterlé, B., Decouttere, C., Vandaele, N., Sangeda, R.Z., Swalehe, O. and Cottone, P. (2021) ‘Factors associated with HIV drug resistance in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: analysis of a complex adaptive system’, Pathogens, 10(12), p. 1535.

Kyotos, K.B., Oduma, J., Wahome, R.G., Kaluwa, C., Abdirahman, F.A., Opondoh, A., Mbobua, J.N., Muchibi, J., Bagnol, B., Stanley, M., Rosenbaum, M. and Amuguni, J.H. (2022) ‘Gendered barriers and opportunities for women smallholder farmers in the contagious caprine pleuropneumonia vaccine value chain in Kenya’, Animals, 12(8), p. 1026.

Larson, E., George, A., Morgan, R. and Poteat, T. (2016) ‘10 best resources on … intersectionality with an emphasis on low-and middle-income countries’, Health Policy and Planning, 31(8), pp. 964–9.

Let’s Learn Public Health [YouTube user] (2017) ‘What makes us healthy? Understanding the social determinants of health’, YouTube, 25 June. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=8PH4JYfF4Ns (accessed 17 June 2025).

Lynch, I., Middleton, L., Naemiratch, B., Fluks, L. and Sobane, K. (2023) Practical Pathways to Integrating Gender and Equity Considerations in Antimicrobial Resistance Research, ICARS/IDRC [online]. Available at: https://icars-global.org/ knowledge/ practical-pathways-integrating-gender-and-equity-considerations-in-antimicrobial-resistance-research/ (accessed 6 June 2025).

Manandhar, M., Hawkes, S., Buse, K., Nosrati, E. and Magar, V. (2018) ‘Gender, health and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 96(9), pp. 644–53.

Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T. and Taylor, S. (2008) ‘Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health’, The Lancet, 372(9650), pp.1661–9 [online]. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/ journals/ lancet/ article/ PIIS0140-6736(08)61690-6/ abstract (accessed 6 June 2025).

Mendelson, M., Laxminarayan, R., Limmathurotsakul, D., Kariuki, S., Gyansa-Lutterodt, M., Charani, E., Singh, S., Walia, K., Gales, A.C. and Mpundu, M. (2024) ‘Antimicrobial resistance and the great divide: inequity in priorities and agendas between the Global North and the Global South threatens global mitigation of antimicrobial resistance’, The Lancet Global Health, 12(3), e516–e521.

Morgan, R., George, A., Ssali, S., Hawkins, K., Molyneux, S. and Theobald, S. (2016) ‘How to do (or not to do) … gender analysis in health systems research’, Health Policy and Planning, 31(8), pp. 1069–78.

Mukamana, L., Rosenbaum, M., Schurer, J., Miller, B., Niyitanga, F., Majyambere, D., Kabarungi. M. and Grace, D. (2022) ‘Barriers to livestock vaccine use among rural female smallholder farmers of Nyagatare District in Rwanda’, Journal of Rural and Community Development, 17(1), pp. 153–75.

Mutua, E., de Haan, N., Tumusiime, D., Jost, C. and Bett, B. (2019) ‘A qualitative study on gendered barriers to livestock vaccine uptake in Kenya and Uganda and their implications on Rift Valley fever control’, Vaccines, 7(3), p. 86.

Nadimpalli, M.L., Marks, S J., Montealegre, M.C., Gilman, R.H., Pajuelo, M.J., Saito, M., Tsukayama, P., Njenga, S.M., Kiiru, J., Swarthout, J., Islam, M.A., Julian, T.R. and Pickering, A.J. (2020) ‘Urban informal settlements as hotspots of antimicrobial resistance and the need to curb environmental transmission’, Nature Microbiology, 5, pp. 787–95.

O’Donnell, M.R., Jarand, J., Loveday, M., Padayatchi, N., Zelnick, J., Werner, L., Naidoo, K., Master, I., Osburn, G., Kvasnovsky, C. and Shean, K. (2010) ‘High incidence of hospital admissions with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis among South African health care workers’, Annals of Internal Medicine, 153(8), pp. 516–22.

Oladimeji, O., Atiba, B.P., Anyiam, F.E., Odugbemi, B.A., Afolaranmi, T., Zoakah, A.I. and Horsburgh, C.R. (2023) ‘Gender and drug-resistant tuberculosis in Nigeria’, Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(2), p. 104.

Pérez-Cuevas, R., Doubova, S. V., Wirtz, V.J., Servan-Mori, E., Dreser, A. and Hernández-Ávila, M. (2014) ‘Effects of the expansion of doctors’ offices adjacent to private pharmacies in Mexico: secondary data analysis of a national survey’, BMJ Open, 4(5), e004669.

ReAct (n.d.) Scoping the Significance of Gender for Antibiotic Resistance [online]. Available at: https://www.reactgroup.org/ wp-content/ uploads/ 2020/ 09/ Scoping-the-Significance-of-Gender-for-Antibiotic-Resistance-IDS-ReAct-Report-October-2020.pdf (accessed 5 June 2025).

Schröder, W., Sommer, H., Gladstone, B.P., Foschi, F., Hellman, J., Evengard, B. and Tacconelli, E. (2016) ‘Gender differences in antibiotic prescribing in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 71(7), pp. 1800–1806.

Shembo, K.D., Kibu, O.D., Tita, A.T., Ayuk, C.N., Ebanga, I. and Esemu, N.B. (2022) ‘Treatment adherence among HIV and TB patients using single and double way mobile phone text messages: a randomized controlled trial’, Journal of Tropical Medicine, 13 August. doi: 10.1155/2022/2980141. PMID: 35996467; PMCID: PMC9392638.

Simpson, J. (2009) Everyone Belongs: A Toolkit for Applying Intersectionality, Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women (CRIAW)/ICREF [online]. Available at https://www.criaw-icref.ca/ publications/ everyone-belongs-a-toolkit-for-applying-intersectionality/ (accessed 5 June 2025).

Taylor, H.A., Dowdy, D.W., Searle, A.R., Stennett, A.L., Dukhanin, V., Zwerling, A.A. and Merritt, M.W. (2022) ‘Disadvantage and the experience of treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB)’, SSM-Qualitative Research in Health, 2, p. 100042.

TDR [YouTube user] (2024) ‘Gender and intersectionality in infectious diseases: Ghana’, YouTube, 14 June [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=MDoRf-hFlNI (accessed 17 June 2025).

TED [YouTube user] (2016) ‘The urgency of intersectionality | Kimberlé Crenshaw | TED’, YouTube, 7 December [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=akOe5-UsQ2o (accessed 5 June 2025).

TED [YouTube user] (2020) ‘What if the poor were part of city planning? | Smruti Jukur Johari’, 28 February [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=sBQv41YbdCk (accessed 17 June 2025).

Tropical Medicine Oxford [YouTube user] (2024) ‘Sonia Lewycka: One Health interventions to combat antimicrobial resistance’, YouTube, 17 September [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=CImiMU6Rdps (accessed 5 June 2025).

Tukahirwa, L., Mugisha, A., Kyewalabye, E., Nsibirano, R., Kabahango, P., Kusiimakwe, D., Mugabi, K., Bikaako, W., Miller, B., Bagnol, B., Yawe, A., Stanley, M. and Amuguni, H. (2023) ‘Women smallholder farmers’ engagement in the vaccine chain in Sembabule District, Uganda: barriers and opportunities’, Development in Practice, 33(4), pp. 416–33.

UN Women (2015) ‘Preventing conflict transforming justice securing the peace: a global study on the implementation of United Nations Security Council resolution 1325’, 12 October [online]. Available at: https://www.un.org/ peacebuilding/ sites/ www.un.org.peacebuilding/ files/ documents/ globalstudywps_en_web.pdf (accessed 6 June 2025).

United Nations (UN) (1966) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [online]. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/ en/ instruments-mechanisms/ instruments/ international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights (accessed 6 June 2025).

United Nations (UN) (n.d. 1) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’ [online]. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/ goals/ goal5 (accessed 6 June 2025).

United Nations (UN) (n.d. 2) ‘UN Women Strategic Plan 2022–2025’ [online]. Available at: https://www.unwomen.org/ en/ un-women-strategic-plan-2022-2025 (accessed 6 June 2025).

Willis, L.D. and Chandler, C. (2019) ‘Quick fix for care, productivity, hygiene and inequality: reframing the entrenched problem of antibiotic overuse’, BMJ Global Health, 4, e001590 [online]. Available at: https://gh.bmj.com/ content/ 4/ 4/ e001590 (accessed 5 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2012) Global Action Plan to Control the Spread and Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Geneva: WHO [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ publications/ i/ item/ 9789241503501 (accessed 6 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018) Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Together: Working Paper 1.0 – Multisectoral Coordination, Geneva: WHO [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ publications/ i/ item/ tackling-antimicrobial-resistance-together-working-paper-1.0-multisectoral-coordination (accessed 6 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) Incorporating Intersectional Gender Analysis into Research on Infectious Diseases of Poverty: A Toolkit for Health Researchers, Geneva: WHO, 15 September [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ publications/ i/ item/ 9789240008458 (accessed 6 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2023) People-centred Approach to Addressing Antimicrobial Resistance in Human Health: WHO Core Package of Interventions to Support National Action Plans, Geneva: WHO [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ publications/ i/ item/ 9789240082496 (accessed 6 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2024a) Operational Framework for Monitoring Social Determinants of Health Equity, Geneva: WHO, 18 January [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ publications/ i/ item/ 9789240088320 (accessed 6 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2024b) Addressing Gender Inequalities in National Action Plans on Antimicrobial Resistance: Guidance to Complement the People-centred Approach, Geneva: WHO, 16 September [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ publications/ i/ item/ 9789240097278 (accessed 6 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (n.d. 1) ‘Health equity’ [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ health-topics/ health-equity#tab=tab_1 (accessed 6 June 2025).

World Health Organization (WHO) (n.d. 2) ‘One Health’ [online]. Available at: https://www.who.int/ health-topics/ one-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed 6 June 2025).

Zinsstag, J., Schelling, E., Waltner-Toews, D., Whittaker, M. and Tanner, M. (eds) (2015) One Health: The Theory and Practice of Integrated Health Approaches. Wallingford: CABI.

Acknowledgements

This free course was collaboratively written by Rosie Steege, Katy Davis, Abriti Arjyal and Stephany Veuger, and was reviewed by Aisling Third, Terri Collins, Rachel McMullan, Sally Theobald and Meenakshi Monga.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Images

Course image: peopleimages12/123rf

Figure 1: reproduced with permission of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, NJ

Figure 2: Göran Dahlgren and Margaret Whitehead

Figure 3: Simpson (2009), redrawn by The Open University; Simpson notes that the examples provided in the wheel are not exhaustive

Figure 4: Dias, Brouwer and van de Beek (2022)

Figure 5: Charani et al. (2021)

Figure 6: Nadimpalli et al. (2020)

Figures 7 and 8: HERD International

Figure 9: World Health Organization, available under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/deed.en

Text

‘Gender matters in global health …’: Global Health 5050 (n.d.)