Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 7:12 PM

Unit 1 – What is trauma?

Introduction

You will begin this unit by reading an overview of the International Rescue Committee to become more familiar with the work they do globally which has informed this course.

After that you will read a poem which explores losing your teen years to the outbreak of war, the traumas that come with war and the impact on a person, their family and their life even after the war has ended. This poem also highlights the themes of war, displacement, loss and grief, and the bittersweet joy of being able to return home without those you lost.

Then you will read about the Healing Classrooms Approach which is a trauma-informed approach to educating refugee students which seeks to combat the negative impacts of toxic stress on children and young people and the focus of this course. The concepts you read about in this unit will underpin the whole of this course and be relevant to each future unit you work through.

You will review various tools and resources and complete tasks to strengthen your understanding of trauma and complete a short end of unit test to further solidify your learning. You will finish with an overview of individual and collective trauma and guidance on how to look after your own mental wellbeing while working with people impacted by trauma.

Unit 1 Objectives

Unit 1 Objectives

- Explain the impacts of trauma and toxic stress on displaced students’ wellbeing and learning.

- Understand the impacts adverse childhood experiences can have on physical and mental wellbeing.

- Examine the different types of trauma including individual and collective trauma.

International Rescue Committee (IRC)

The International Rescue Committee responds to the world’s worst humanitarian crises and helps people whose lives and livelihoods are shattered by conflict and disaster to survive, recover, and gain control of their future.

Founded at the suggestion of Albert Einstein in 1933 to assist refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, the IRC has since become a global humanitarian organisation with programming in over 50 countries.

IRC UK offers various programmes. This Open University course is part of the Healing Classrooms Approach – IRC's global trauma-informed teacher training programme.

What is the Healing Classrooms Approach?

Healing Classrooms is the IRC’s global teacher training programme which aims to help educators to support children’s recovery from trauma by creating safe and stable environments in schools.

The IRC’s Healing Classrooms – built on 30 years of education in emergencies experience and a decade of research and field testing – offers children a safe, predicable place to learn and cope with the consequences of conflict and displacement.

Unlike many education programmes that focus solely on teaching academic subjects, Healing Classrooms builds children’s social-emotional skills as well as their capacities to learn. This approach is based on research that shows social-emotional learning programs improve students’ life skills, behavior and academic performance.

To help teachers, school personnel and communities create Healing Classrooms, the IRC:

- Supports and trains teachers to establish safe, predictable and nurturing environments.

- Creates and provides teaching and learning materials to build students’ academic and social-emotional skills.

- Connects parents and caregivers with schools.

The Healing Classrooms Approach originated in 1997. It was the brainchild of IRC staff in the CRRD (Crisis Response, Recovery and Development) team who saw a need for robust teacher training for educators in refugee camps as a key method to help children to heal.

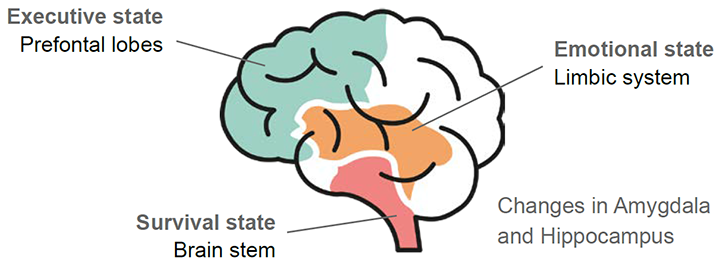

Healing Classrooms is based on the fact that children who do not feel safe cannot learn. Their brains are stuck in survival mode, and they are focusing on monitoring potential threats above all else.

In order for children to make friends, progress in their studies and to heal from any trauma they have experienced, they need to be in safe spaces where there are trusted adults they can seek out if they need support.

The techniques underpinning Healing Classrooms were developed using teacher and student interviews in Ethiopia, Lebanon and Guinea and after finding out which strategies could help educators to create healing classrooms in their various contexts, the strategies were field-tested for 6 years in various crisis-affected areas.

Since its inception, Healing Classrooms has come a long way. It now been adapted to meet the needs of children in our RAI (Resettlement, Asylum and Integration) settings in Europe and the United States to help children in mainstream schools to feel safe and settle into their new countries.

It has also been adapted numerous times to fit different country contexts, different age groups and stages of education. Currently, the IRC is on the ground providing education to children and youth in 20 countries affected by conflict and crisis.

Healing Classrooms looks different in every country as it is adapted to meet the specific needs of the educators and the communities they work within.

Healing Classrooms in the UK

Here in the UK, Healing Classrooms training sessions have been running since 2022 and educators across all ages from EYFS to university have taken part. Our team is made up of former teachers and behaviour specialists who have adapted the IRC’s Healing Classrooms programme to the UK context.

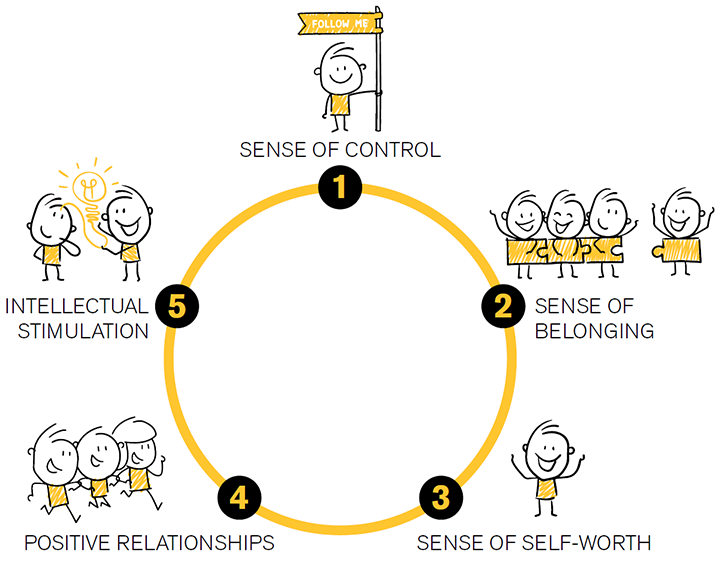

In the UK, Healing Classrooms is broken down into three steps:

Step 1: Preparing a Safe Place to Land

This step focuses on creating a sense of control and self-worth for students.

Step 2: Building a Community for Learning

This step focuses on creating a sense of belonging and meaningful relationships.

Step 3: Fostering Academic Success

This step focuses on creating intellectually stimulating environments for all students by using culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP).

In the final three units of this course, you will work through strategies and case studies linking to each of these three steps, clarifying exactly how to achieve these in your setting.

Refugees bring more than they carry

You may fall into the habit of viewing newcomer refugee students through a deficit-based lens. For example, "My student can't speak enough English to take part in this lesson", "This student has got gaps in his education, and he is very far behind the rest of my class" or "This student is struggling so much with the impacts of trauma that I don't know where to begin in supporting her".

The Healing Classrooms Approach turns this perspective on its head and views refugees through an assets-based lens.

When fleeing conflict, refugees can only carry so much. But, even having left most of their belongings behind, they bring so much to their communities – skills, traditions, stories, dreams, families and so much more.

Due to the immense challenges people have faced before fleeing, during their journey and now, upon arrival in the UK, they may need that extra helping hand to get their lives back on track.

The Healing Classrooms Approach aims to help children to recover from any potential trauma by creating safe schools where trusted adults help them to learn in creative ways and new friends help them to settle in their new communities.

Schools are ideal places for this healing to happen as they are already places filled with aspirations, learning and fun! The Healing Classrooms Approach helps schools to tailor their existing resources and skills to enable a safe place for refugee children to land and take their first steps towards a happier future.

When children who are refugees first arrive in your school, it can be overwhelming to try to figure out what needs to be put in place to support your new students. The Healing Classrooms Approach sets out the first steps to welcoming new children and giving them what they may need to ensure a smooth start to their new school life.

Watch this video to explore the idea that refugees bring more than they carry.

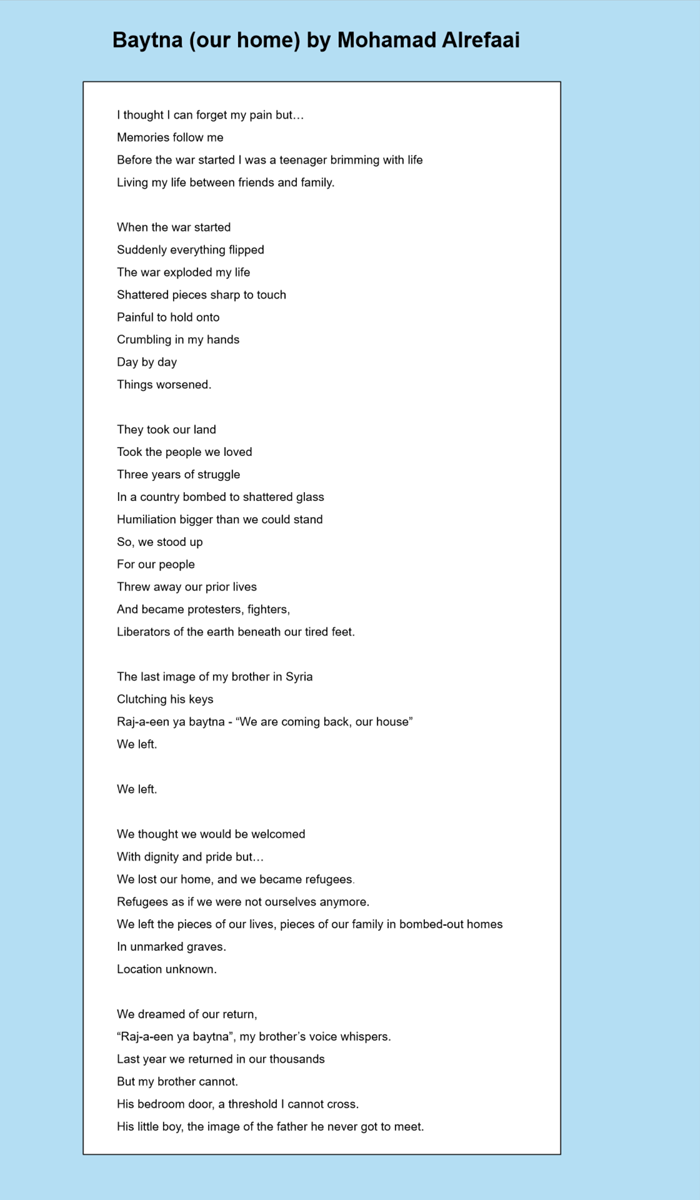

Poem – Baytna (our home) by Mohamad Alrefaai

In his poem below, Mohamad Alrefaai explores losing your teen years to the outbreak of war, the many traumas that come with war and the impact on a person, their family and their life even after the war has ended.

It also highlights the themes of war, displacement, loss and grief, and the bittersweet joy of being able to return home without those you lost.

You can listen to the poem if you prefer. Or why not read and listen at the same time?

Transcript

These audio poems are a great resource to use in class.

As you work through this unit, keep in mind the various experiences, both positive and negative, that a student may have encountered and how they may provide strength or challenges for them as they rebuild their life in the UK.

Many, but not all students, will be impacted by trauma from some of their negative experiences that caused them to leave their home but also from the journey they were forced to make and even the hostility they may have faced upon arrival in the UK.

For the rest of this unit, you will explore how trauma can impact a child's brain development and how you as an educator can provide appropriate support to your students.

What is trauma?

Trauma is a common consequence of witnessing or experiencing something shocking, dangerous or life-threatening.

Trauma jeopardises our brain health which can manifest into difficulties learning new content, controlling behaviour, remembering key information, regulating emotions and more. Trauma can be especially damaging to the brains of children as they are still developing.

Later in this unit, you will explore the specific impacts trauma and toxic stress can have on a child and how it can affect their ability to concentrate and learn.

Creating Healing Classrooms to welcome refugee children can give them a safe space to recover, settle and begin to learn. Children are incredibly resilient, but they need trusted adults and communities to help them get back on track with their learning, personal development and thinking of their new future in the UK.

| Ability to form and maintain healthy relationships and trust. |

| Ability to focus, concentrate and learn. |

| Sense of control and autonomy. |

| Sense of belonging and community. |

| Sense of self-worth. |

Trauma can impact a child significantly as shown in the list above. Schools can be ideal places to help a child’s recovery, but they can also be places where trauma is worsened if trauma-informed care is not embedded in a school.

Next, you will review common risk factors that can hinder a child’s recovery and common protective factors which can support them to heal.

Risk and protective factors to recovery

Various factors determine how well a child will cope with trauma and how quickly they might recover.

Those factors can include their family situation and support networks (such as local religious or community centres), their financial situation, the services they are able to access, their opportunities to participate in their new community, the language support they can access, mental health support available to them, accessibility of healthcare and any pre-existing health issues.

Consider how your school or organisation can help to reduce the risk factors your students are facing. This could include signposting families to services, accompanying families to appointments, reaching out on their behalf to access support, utilising school funding to support their children, ensuring good English language support, providing opportunities for friendships within school, and using interpreters when necessary.

You can review common risk and protective factors in the following table:

| Risk factors | Protective factors |

|---|---|

| Lack of language support (no English tutor, no translated documents, no interpreter used in meetings). | Opportunities for relationship building. |

| Limited support during transition to new school. | Engaging parents/caregivers. |

| Punishment-based strategies to improve behaviour (e.g., detention, shouting, withdrawal from activities). | Programmes to meet learning gaps and talents. |

| Environment not inclusive of various cultures/religions. | Use of interpreters (online or in-person). |

| Neglecting other factors which can be a target for discrimination (race, sexuality, religion, SEND, etc.). | Continued support throughout the year. |

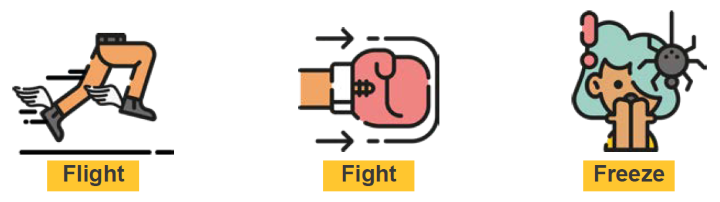

Immediate trauma response

During a dramatic event, our brains go into survival mode. The primitive brain takes over, and our responses are involuntary. How a person responds during a traumatic event may leave them with feelings of shame or helplessness, especially if they have the freeze or flight response.

They may feel like they let the trauma happen to them or others by not leaving, helping others in the moment or fighting but it is important to know that we have no control over our immediate trauma responses.

It can be helpful for students to know this information in an age-appropriate way and can help them process feelings of guilt or shame based on their response during a traumatic event.

Task 1: Long term impacts: What is toxic stress?

Task 1: Long term impacts: What is toxic stress?

Watch this video about toxic stress.

While you are watching, consider how toxic stress impacts on a child’s healthy development.

Has exploring the topics of trauma and toxic stress changed the way you might view and respond to your students’ behaviours? If so, how?

Make some notes in the text box below.

Comment

An educator with knowledge of toxic stress and the impacts it can have on a child's brain development can have a better understanding of why a student may be behaving the way they are.

This can help the educator act from a place of compassion and empathy rather than going straight to behaviour management strategies which can sometimes cause further harm and re-traumatisation.

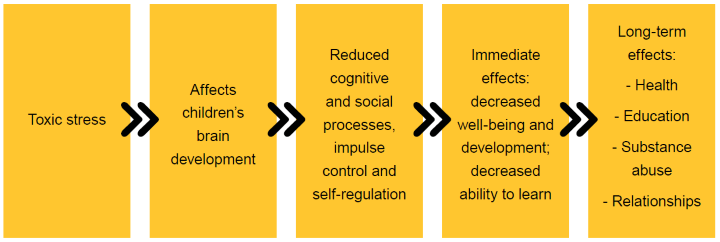

Effects of toxic stress

The video above pointed to the impact of toxic stress on a child’s developing brain. Let's breakdown what you have just watched in the video in more detail to fully explore this impact.

Read the first slide about The Brain. Then click on the Next button to view more slides.

Combating toxic stress

What happens if you don't try to combat toxic stress?

The potential future consequences of not dealing with toxic stress indicate the importance of providing appropriate support to students now.

Over the five units of this course, you will be reviewing key strategies to provide this support.

You will now look at specific impacts caused by toxic stress on young people’s behaviour in the classroom.

Impacts of toxic stress

Look at the impacts associated with toxic stress in the table below.

Reflect on your students and their behaviour in class. Do you see any of these in your daily work? Consider how you might respond differently to these behaviours knowing they could be indications of toxic stress.

| Cognitive impact | Physiological impact | Emotional impact | Behavioural impact |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

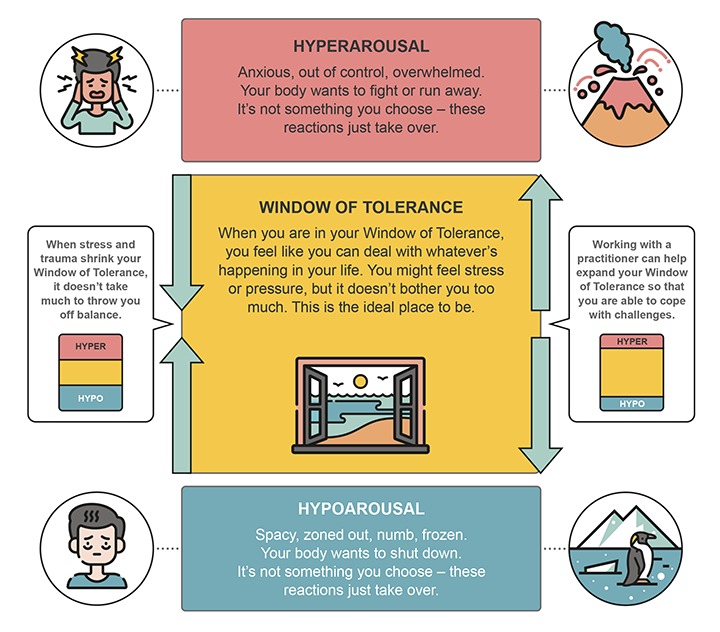

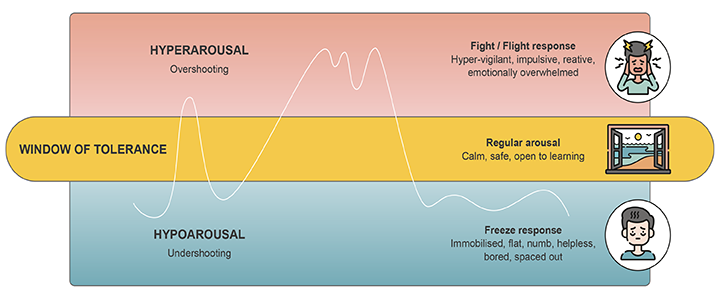

The window of tolerance

The behaviours in the table you have just reviewed arise when a person is pushed out of their window of tolerance.

The window of tolerance is similar to a person’s comfort zone. there are certain places, activities and groups of people who you may feel calm, comfortable and confident with but there may be other situations where you would feel nervous, panicked or uneasy (for example, speaking before a large crowd or your first day working as a teacher).

For people who have lived safe, stable and secure lives with strong social connections, their window of tolerance will enable them to cope with most situations without panicking or feeling under threat.

However, for a person who has experienced trauma, their window may be much smaller than it used to be and everyday situations such as a noisy classroom, a fire alarm or a slamming door may be enough to push them out of their window and into either hyperarousal or hypoarousal.

Read the diagram below to learn more about each response.

When pushed out of their window of tolerance, students can go into hyperarousal which is where they may feel anxious, out of control and in a fight or flight mode. They might appear to have too much energy and be fidgeting or tapping.

Students can also go into hypoarousal which can leave them feeling lethargic, spaced out or frozen. Neither of the responses are chosen by the student. They are, just like the fight, flight, freeze response, involuntary.

The window of tolerance is the state in which we can best learn, connect and play, be present and self-soothe. When a student is within their window of tolerance their internal voice is quiet, and they can better tolerate challenges independently.

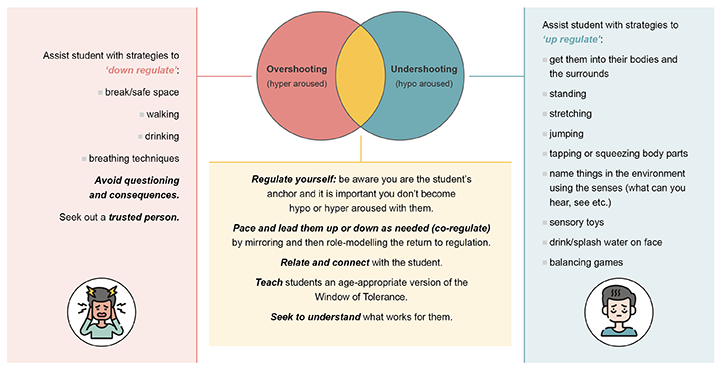

When a child is out of their window of tolerance it is important to either energise them or calm them down to help them regulate their body and their behaviour.

Grounding and mindfulness exercises can be helpful to a child who is hyperaroused and physical activities can be helpful for a child who is hypoaroused.

How can you bring a person back into their window of tolerance?

Read through the diagram below to learn more about bringing a person back into their window of tolerance

Next, you will explore the method of co-regulation, a useful tool for educators to use when working with children to return to their window of tolerance.

Co-regulation

Co-regulation can be an effective way of helping a student return to their window of tolerance.

Remember you must stay calm in these situations and not mirror the panic or frustration of the student – even if what you are witnessing is upsetting you.

The images below provide a helpful guide for educators to remember so that they can effectively co-regulate with a student.

You are their anchor in the storm, and the student needs you to stay calm, collected and objective when they are out of their window of tolerance.

In the task that follows, you will work through an example from a teacher working with a student impacted by toxic stress. You will be asked to apply the technique of co-regulation and consider how this teacher can adapt their response should they be faced with a similar situation in the future.

Task 2: Working with a student impacted by toxic stress

Task 2: Working with a student impacted by toxic stress

Part 1

Read the following account from a teacher working with a student impacted by toxic stress.

I remember when I was working with a class of refugee students, teaching them intermediate English. One student, Samir was so confident speaking in English and would be the first to jump in to answer any questions.

However, in one class, I was preparing my students for their exam, and we needed to focus on writing, as it was the weakest area for the whole class. Samir wasn’t writing anything but was answering verbally instead.

I asked him to write his answer so the other students wouldn’t take his answer and write it down and he refused. Taken aback by this usually polite student, I said “you need to write because this is the written exam”. He refused again and the other students stopped to watch what was going on.

The atmosphere in the room changed and became quite tense. “If you’re not going to do the work then you’ll have to leave”, I said. Samir got up and left, and the rest of the class was silent until the students finished their work and left. I couldn’t understand why Samir had been so rude out of the blue and refused to do his work.

I caught up with Samir the following week and chatted to him about what had happened and how we were both upset by it. He explained that he suddenly felt stressed, nervous about getting the answer wrong, and suddenly felt like he had to get out of the classroom.

Everything you have reviewed so far in the course could apply to any person with any kind of trauma and is not specific to refugees and asylum-seeking people.

In the following section, you will review some key information about the global situation of forced displacement and then zoom in on the specific types of trauma that a forcibly displaced person may have experienced.

This background knowledge can help inform your practice and allow you to lead informed conversations with your students about why people flee their homes, the types of experiences they may have on their journey to safety, and the challenges they may face upon arriving in a resettlement country.

Trauma and toxic stress for refugee and asylum-seeking people

You will now read some key information about the current global issue of forced displacement. This can help develop your foundational knowledge about this issue and consider the impacts on refugee and asylum-seeking children you work with and may work with in the future.

Currently, over 117 million people are forcibly displaced globally (UNHCR, 2024) and the numbers increase every single day.

People are displaced “as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order” (UNHCR, 2022). This figure is made up of internally displaced people, asylum seekers, refugees and undocumented forced migrants. It is the highest it has been in recorded history. We have more forcibly displaced people today than we did at the height of WW2.

In 2022, 53% of those under the protection of the UNHCR were from just three countries: Syria, Ukraine and Afghanistan and of those under the care of the UNHCR, 38% were hosted in just five countries: Turkey, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Colombia, Germany and Pakistan.

Of all forcibly displaced people globally, roughly 86% stay in neighbouring countries. Very few people can afford to make the trips to Europe or North America and many of those who attempt to reach these countries lose their lives on the perilous journeys they are forced to take in the absence of safe routes.

As most people struggle to find safe countries, with the support they need to meaningfully rebuild their lives, 1.9 million babies were born with refugee status in 2022. Overall, it is estimated that less than 1% of displaced people are ever able to resettle and find a new life in safety and security.

Due to ongoing conflicts and crises across the globe these numbers increase daily. Climate change is predicted to have a significant impact on the numbers of people becoming forcibly displaced and this is already happening in places most vulnerable to high temperatures, extreme weather events and rising sea levels.

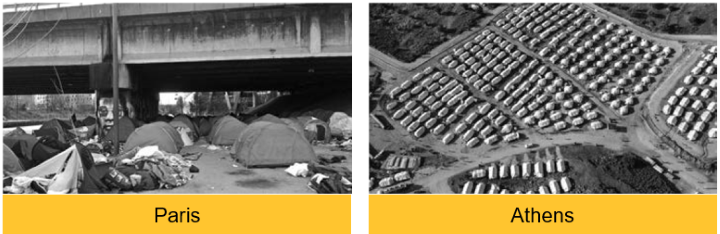

Most refugees live in refugee camps rather than being able to live with the host country’s communities in houses or apartments.

Here are some of the largest refugee camps in the world today. Click on each tile to learn more.

Europe

Across Europe, refugee camps and detention centres have been on the rise since 2015. The conditions in most refugee camps have adverse impacts on people’s physical and mental health. Many refugees living in camps suffer from skin conditions, mental health issues and digestive issues due to the substandard conditions.

Refugees often have to pass through several countries to be reunited with family members or to find a country which can offer language classes, legal employment, safe housing, and education for their children so they can meaningfully rebuild their lives.

Several borders have been closed in Europe since 2016 to stop the free movement of people seeking sanctuary which has caused increasing numbers of people to get stuck in countries like Greece and Italy.

A closure of programmes offering safe routes from conflict-affected countries directly to safe countries has caused people to spend years trying to reach the countries where their friends and family are without proper assistance from organisations or governments, instead having to trust in smugglers to cross borders by land, air or sea.

Once children and their families arrive in our towns and schools, they may require support to feel safe and welcome as they may have experienced severe hostility, violence and abuse on their way to safety. Unfortunately, people seeking sanctuary are often treated with scepticism rather than being given the compassion and empathy that we would all need if we were forced to flee our homes in the UK.

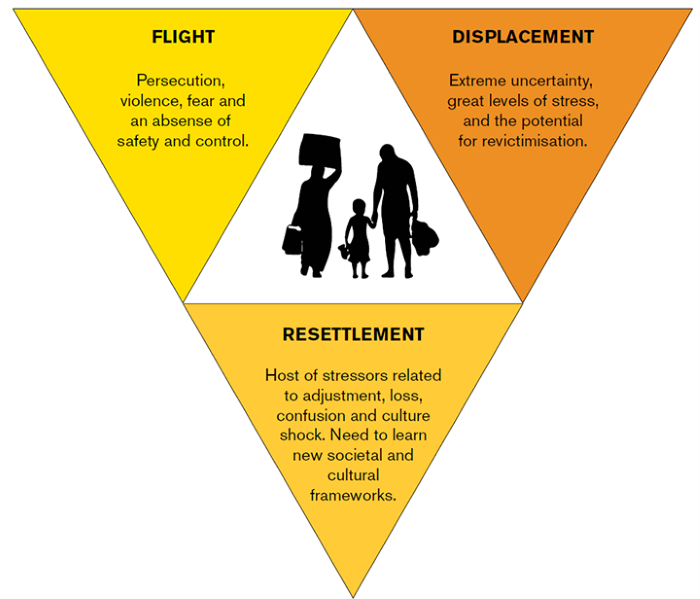

You will now review a useful tool for imagining what a person may have experienced before entering your classroom – the Triple Trauma Paradigm.

The Triple Trauma Paradigm

The Triple Trauma Paradigm is a tool to help you better understand what families may have experienced and the various traumas they may have survived in order to get to a safe country. It can help you to better understand the potential needs of families and the students you teach.

It is not to suggest that all refugees have had the same experiences, as every person has their own story and their own responses to what they have experienced.

Unfortunately, many refugees around the world will never reach the stage of resettlement or the chance to return to their country and live in safety. In many cases, displacement is protracted – the average duration of displacement is known to be 20 to 25 years – and generations of families are born and live their whole lives in refugee camps and settlements.

Task 3: Traumatic experiences

Task 3: Traumatic experiences

Part 3

Watch this video of Habib and how his lived experience of forced displacement fits into the Triple Trauma Paradigm.

Reflect on the challenges Habib faced upon arriving in the UK and how the various adults in Habib’s life provided him support when he needed it most.

Comment

This 3-part activity highlights the various traumas an individual may experience during the arch of displacement (flight, displacement, resettlement). Keep these potential experiences in mind when working alongside refugee students and families to help you better contextualise their responses, behaviours and actions.

Also keep in mind that every person has their own story and their own reactions to what has happened to them. Having this knowledge can help educators better understand and support their students.

Individual trauma and collective trauma

There are many types of trauma.

Two that are most commonly experienced during war, conflict and forced displacement are individual trauma and collective trauma.

What is individual trauma?

- An experience of traumatic events that impacts an individual.

- Survivors can sometimes experience feelings of guilt and shame around their reactions.

- These experiences can impact a person’s self-worth, behaviour, mental health and aspirations for what they want their life to look like in the future.

What is collective trauma?

- Shared experience of traumatic events that impact a community or society.

- Can be experienced as a group based on religion, race, sexuality, gender, culture and more.

- These experiences can become held in the collective memory and body of an individual and the group, impacting their lives in different ways.

- These can be experiences that happened generations ago but still have consequences on people today.

To solidify your understanding of individual and collective trauma, complete the following task.

Task 4: Individual or collective trauma?

Task 4: Individual or collective trauma?

Part 1

Now check your understanding of individual and collective trauma.

Part 2

As you return to your classroom or learning space this week, how will any of this week's content impact the way you interact with students, plan their learning activities or support them in another way?

What are three key points you will share with your colleagues?

What steps will you take to ensure your fellow educators can make use of this knowledge in your workplace?

Make notes in the text box below.

Comment

As demonstrated in the activity above, the students have likely experienced a mixture of individual and collective traumas both forcing them to flee and occurring during their displacement.

Utilise the knowledge you gained from the learning on trauma, toxic stress, the window of tolerance, the triple trauma paradigm and the two types of trauma just discussed, to help guide how you work alongside your refugee students and what kinds of support you offer to them to help them resettle in your school and community.

Supporting students and young people can take its toll on you too.

You will now work through the final section of the unit which focuses on some impacts of supporting those with trauma: compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma.

Educator wellbeing and impacts

Wellbeing and impacts of working with students impacted by trauma

Working in an environment where you are supporting those impacted by displacement and trauma can take its toll on educators and other school staff. It is important to monitor your wellbeing continuously as you do this work.

Vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue can come about from working in high-pressure environments where you are hearing traumatic stories on a regular basis.

As you read the following impacts, reflect on your own wellbeing.

| Vicarious trauma | Compassion fatigue |

|---|---|

Dealing with personal trauma is challenging but so is helping others work through their trauma – and it may result in vicarious trauma. Vicarious trauma is the accruing effect of being exposed to someone else’s trauma – trauma that you have not personally experienced, but you’ve learned about from others. | People feel that they cannot commit any more energy, time, or money to the plight of others because they feel overwhelmed or paralysed by pleas for support and that the world’s challenges are never-ending. |

This is a type of trauma.

|

This is not a type of trauma.

|

How to identify vicarious trauma:

| How to identify compassion fatigue:

|

If you are experiencing any of these signs, speak to your colleagues or senior leadership team to gain the support you need. If you feel the signs are impacting your daily life significantly, reach out to your GP for further support and consider adaptions your school may need to make to ensure you are well enough to continue your work in the future.

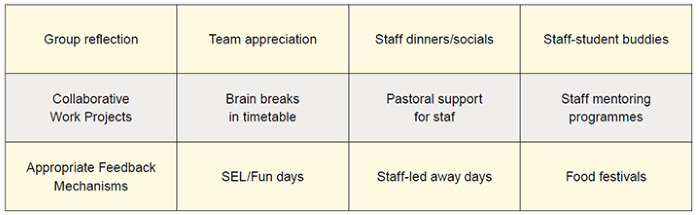

Community care

Community organisers and most non-Western cultures have stronger focuses on community care than self-care. Community care can solidify practices long-term to support everyone in school from staff to students to their families.

Recommended strategies to promote and maintain staff wellbeing can help staff who need support now and build resilience for those who may need it in the future.

In the following task, you will review some examples of community care strategies that could be used to support staff in a school setting.

Task 5: Support for staff in your workplace

Task 5: Support for staff in your workplace

Read through the table of strategies above.

Choose three suggestions and explain what these could look like in your setting and how they could help provide support for staff in your workplace. To make your selection, you may want to consider how well they fit with existing activities or policies you have in your workplace and with any needs, gaps or concerns that have been expressed in staff meetings recently.

If you feel comfortable doing so, take one suggestion to discuss with your senior leadership team or raise in your next staff meeting. If you are not comfortable doing this, consider if you could try one of these strategies on a smaller scale, for example, in your subject department instead of the whole school.

Make notes in the text box below.

Comment

This activity demonstrated the various ways schools can adapt their policies, procedures, routines and ways of working to better support their staff and student community.

Consider which ones may best fit your setting and start conversations with management/leadership to see what can be improved in your setting to better support everybody in school.

Unit 1 Summary

In this unit, you read an overview of the International Rescue Committee to become more familiar with the work they do globally which has informed this course.

You reflected on the Healing Classrooms Approach which is a trauma-informed approach to educating refugee students which seeks to combat the negative impacts of toxic stress on children and young people and the focus of this course. The concepts you read about in this unit underpin the whole of this course and be relevant to each future unit you work through.

You reviewed various tools and resources and completed tasks to strengthen your understanding of trauma. And you finished this unit with an overview of individual and collective trauma and guidance on how to look after your own mental wellbeing while working with people impacted by trauma.

You will now move to Unit 2 – Working towards healing.

But before you do this, please complete a short multiple-choice quiz to solidify your learning.

Moving on

References

British Medical Association (2024) Vicarious trauma: signs and strategies for coping [Online]. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/your-wellbeing/vicarious-trauma/vicarious-trauma-signs-and-strategies-for-coping (Accessed 27 October 2025).

UNHCR (2022) Refugee Data Finder [Online]. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (Accessed 16 June 2025).

UNHCR (2024) Reports: Global Appeal 2025 [Online]. Available at: https://reporting.unhcr.org/globalappeal#:~:text=117.2%20million%20 people%20will%20be,2023%2C%20according%20to%20UNHCR’s%20estimations (Accessed 16 June 2025).

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to the real children and families whose stories inspired these case studies and all of the past participants who have shared their examples of good practice which have all helped feed into this course.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Important: *** against any of the acknowledgements below means that the wording has been dictated by the rights holder/publisher, and cannot be changed.

International Rescue Committee (IRC)

572643: Hannah Jacobs and Pal TV for the IRC

573763: stick-figures.com/Shutterstock

573771: strichfiguren.de/ Stock adobe

572756: Francesco Pistilli for International Rescue Committee (IRC)

572772: Mohamad Alrefaai

572775: Semanche/ Shutterstock

572776: Adapted from freepik on Flaticon

574096: Good Ware on Flaticon

British Medical Association (2024)

572932: Wirestock Creators/Shutterstock