Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 22 November 2025, 3:30 PM

Communicable Diseases Module: 24. Provider-Initiated HIV Testing and Counselling

Study Session 24 Provider-Initiated HIV Testing and Counselling

Introduction

In this study session, you will learn about the benefits of HIV testing and your role as a Health Extension Practitioner in counselling and testing for HIV infection, an important prevention measure. The focus of this study session is provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling (PITC) and rapid HIV testing, but other issues such as confidentiality and informed consent will also be addressed.

PITC is HIV testing which is initiated by the health worker either in the health facility or at community level, and is part of the developing role for health workers in preventing the spread of HIV and identifying those individuals at risk and in need of treatment.

All the photographs shown in this study session have been provided by the Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 24

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

24.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 24.1 and 24.3)

24.2 Explain the benefits and barriers of HIV testing. (SAQ 24.2)

24.3 Explain the different modes of HIV counselling and testing. (SAQ 24.3)

24.4 Describe how to recommend HIV testing, and give pre-test counselling, including maintaining confidentiality and obtaining informed consent. (SAQ 24.4)

24.5 Describe how to perform rapid HIV testing using three different test kits, and read and interpret the test results. (SAQ 24.5)

24.6 Explain how to deliver HIV test results and post-test counselling. (SAQ 24.4)

24.1 Benefits and barriers of HIV testing

24.1.1 The benefits of HIV testing

There are several benefits of HIV testing. Firstly, it allows people infected with HIV to gain early access to HIV treatment and care; secondly, it encourages those tested to reduce their high-risk behaviour and avoid transmission to partners; thirdly, it helps HIV-negative people to develop a plan to remain negative; and lastly, it allows couples where one or both is HIV-positive to choose appropriate family planning methods to reduce the risk of infection.

High-risk behaviour in the context of HIV/AIDS refers mainly to sexual intercourse without the use of a condom (see Study Session 25).

In Ethiopia, HIV counselling and testing sites are a key entry point for HIV prevention, treatment, care and support services. It is important for individuals and couples to learn about their HIV status and make informed decisions about their future.

24.1.2 The barriers to HIV testing

Barriers to HIV testing are those obstacles that prevent people from getting tested, either voluntarily or when offered a test by a healthworker. These barriers fall into three categories: client-related, healthworker-related and health facility-related. Examples of client-related barriers include fear of stigma, shame or disapproval attached to something regarded as socially unacceptable, and discrimination (unfair treatment of people found to be HIV-positive). Other client-related barriers include the fear of being ill and dying from a non-curable disease, if the test is positive for HIV infection; the loss of family support; and difficulties of keeping or finding a job.

In this context, a ‘client’ is an individual who wishes to be tested for HIV.

Healthworker-related barriers include the fear of damaging the patient-provider relationship; the unpredictability of the patient’s emotional reaction; lack of time; and fear of overwhelming the client. Examples of health facility-related barriers are lack of space, equipment and supplies.

24.2 Modes of delivering HIV counselling and testing

HIV counselling and testing is central to preventing the spread of HIV infection and identifying those individuals at risk. As discussed in Study Session 20, we can only say that a person has HIV in their blood when they are tested and found to be HIV-positive. In this section, you will learn that there are three different modes of delivering the counselling and testing service: voluntary counselling and testing (VCT), provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling (PITC), and mandatory HIV testing.

Voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) is initiated by the clients themselves. In other words, individuals request HIV testing without the health worker offering or recommending testing. VCT often takes more time than PITC because clients expect, and have allowed time for, additional counselling both before and after a test result. Note that you are not expected to perform VCT yourself. If individuals ask you for HIV testing voluntarily, you should refer them to a health centre that offers VCT.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and health services in many countries, including Ethiopia, promote a policy of provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling (PITC). This means that when trained to do so, you should offer and provide HIV testing and counselling yourself. PITC enables specific clinical decisions to be made and medical services to be offered that would not be possible without the knowledge of a person’s HIV status. A period of pre-test counselling and education should always accompany testing, and people should never be forced to undergo testing against their will.

Remember that under most conditions, an HIV test should only be done after obtaining the informed consent of the individual concerned.

PITC is further divided into diagnostic testing and routine offer. Diagnostic testing is part of the clinical process of determining the HIV status of a sick person, such as someone with TB or other symptoms that suggest possible HIV infection. On the other hand, a routine offer of testing and counselling means offering an HIV test to all sexually active people who seek medical care for other health issues.

Unlike VCT, PITC needs only a brief period of pre-test information/education before performing the test, and can be done in a few minutes. PITC is recommended for countries like Ethiopia where HIV is endemic (always present in the population). PITC is not a replacement for VCT. Instead, it provides an entry point to HIV services, it helps to prevent HIV transmission in the community, and also helps people make healthier choices. Those individuals who are found to be HIV-positive can then be referred into treatment and care.

Under normal conditions, a person would only undergo HIV testing after they have given their informed consent, that is consent based on fully understood information about the test and what the result may mean. A signed consent form is not needed in Ethiopia for PITC (although it is for VCT), but obtaining verbal consent is essential.

Respecting an individual’s rights is an integral part of the process of HIV counselling and testing, and this is often referred to as the ‘3 Cs’ — consent, confidentiality, and access to counselling.

Mandatory HIV testing, on the other hand, does not require the consent of the individual about to be tested. It is done by force or without informed consent, and is usually performed at the request of a court in cases involving rape or other sexual assault.

24.2.1 The five steps in PITC

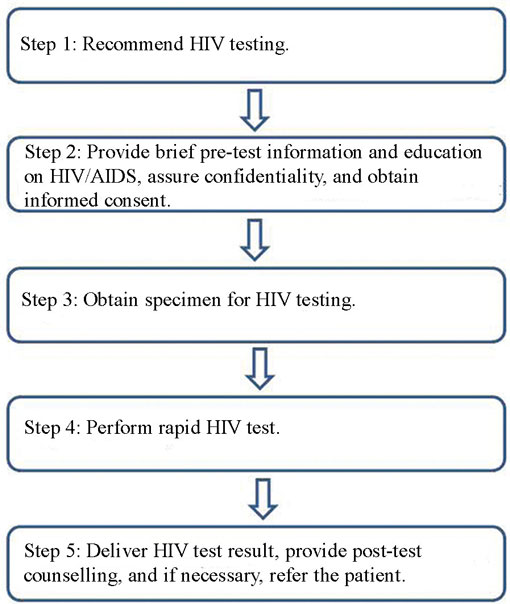

The flow chart in Figure 24.1 illustrates the five key steps involved in PITC. As PITC is central for the work of Health Extension Practitioners, we will focus on PITC for the remainder of this study session. Each step will be explained in detail.

24.3 Step 1: How to recommend HIV testing

Diagnostic testing is part of the clinical process of determining the HIV status of a sick person whom you suspect may be infected with HIV. If the person presents with symptoms consistent with HIV infection, explain that they will be tested for HIV as part of their clinical check-up.

The following is an example of how a trained health worker might recommend a diagnostic HIV test:

‘As you told me, you have diarrhoea that has lasted three months and you have lost a lot of weight. I want to find out why. In order for us to diagnose and treat your illness, you need a test for HIV infection. Unless you object, I will conduct this test.’

Below is an example of how to make a routine offer for HIV testing:

‘One of our guidelines is to offer everyone the opportunity to have an HIV test, so that we can provide you with care and treatment while you are here and refer you for follow-up afterwards. Unless you object, I will conduct this test and provide you with counselling and the result.’

A routine offer is made to sexually active people regardless of their initial reason for seeking medical attention.

24.4 Step 2: Pre-test counselling, confidentiality and informed consent

24.4.1 Pre-test information and education on HIV/AIDS

Before testing, you should provide the individual about to be tested with information on HIV/AIDS, and, importantly, give them enough opportunity to ask questions. You should include the basic facts about HIV, its transmission and prevention; the importance of knowing one’s own HIV status and the advantages of disclosing one’s own HIV status to family members, close friends and others. Also, explain about follow-up support and the services available if the test is positive for HIV. Box 24.1 summarises the key information you should provide as part of pre-test counselling and education on HIV/AIDS.

Box 24.1 Pre-test information/education as part of PITC

HIV is a virus that destroys parts of the body’s immune system. A person infected with HIV may not feel sick at first, but slowly the body’s immune system is destroyed. They then become ill and are unable to fight infections. Once a person is infected with HIV, they can transmit the virus to others unless they practice preventative measures and safe sex (Study Sessions 25 and 29).

HIV can be transmitted:

- through exchange of HIV-infected body fluids such as semen, vaginal fluid or blood during unprotected sexual intercourse.

- through HIV-infected blood transfusions.

- through sharing sharp cutting or piercing instruments.

- from an infected mother to her child during pregnancy, labour and delivery, and during breastfeeding.

HIV cannot be transmitted through:

- hugging, shaking hands, eating together, sharing a latrine, or mosquito bites.

A blood test is available that enables a person’s HIV status to be determined.

If the HIV test is positive, knowing this will help you to:

- protect yourself from re-infection, and your sexual partner(s) from infection.

- get early access to chronic HIV care and support, including regular follow-up and support, treatment for HIV, and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis (preventative treatment with antibiotics).

- cope better with HIV infection and be able to make future plans. For pregnant mothers or for married couples intending to have a child in the future, it gives a chance of early access to services for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV (Study Session 27).

If the HIV test is negative, knowing this will help you explore ways to remain HIV-negative.

24.4.2 How to assure confidentiality

Assure the person about to undergo testing that the result is confidential, and emphasise the following points:

- The result will only be shared with him or her.

- He/she decides to whom to disclose the result of the test.

- The result will only be provided to another person with his/her written consent. If the result of the test is needed to ensure appropriate clinical care, explain the advantages of sharing the result with the medical team.

24.4.3 How to obtain informed consent

After providing pre-test counselling on HIV/AIDS and assuring confidentiality, you need to confirm the individual’s willingness to proceed with the test. You should ask them whether they agree with you and give consent for the test to be done. If they give their consent, make sure they are willing to discuss the implications of the test with you once the result is known.

Remember, informed consent can be given verbally for PITC.

24.5 Step 3: Obtaining a specimen for HIV testing

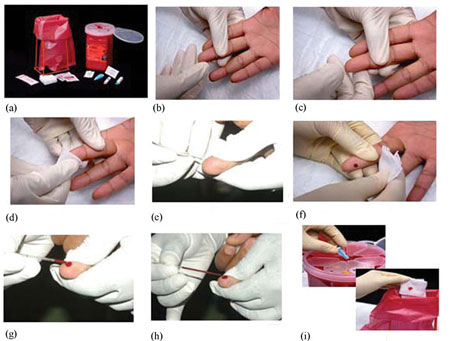

Specimens used for HIV testing include serum, whole blood, or oral fluids. In Ethiopia, whole blood is used for rapid HIV testing. The blood specimen is obtained by a finger prick (as outlined below and illustrated in Figure 24.2).

1 Prepare a container for disposing of sharp instruments; also prepare gloves, lancet, alcohol swab, cotton swab, pipette, capillary tube, the test kits, and other necessary materials (Figure 24.2a).

2 Wash your hands with an antiseptic soap and water.

3 Wear clean gloves.

4 Position the hand of the person to be tested palm-side up. Select the softest finger; avoid those fingers that have calluses or hardened skin (Figure 24.2b).

5 Massage the chosen finger to help the blood to flow (Figure 24.2c).

6 Clean the fingertip with an alcohol swab (Figure 24.2d). Start in the middle of the finger and work outwards; this will prevent contamination of the cleansed region. Allow the finger to dry.

7 Hold the finger and firmly place a new sterile lancet off-centre on the fingertip. Firmly press the lancet to puncture the fingertip. (Figure 24.2e).

8 Wipe away the first drop of blood with a sterile gauze pad or cotton ball. Apply intermittent pressure in the base of the punctured finger several times (Figure 24.2f).

9 Blood may flow best if the finger is held lower than the elbow. Touch the tip of the capillary tube to the drop of blood (Figure 24.2g).

10 Ensure you fill the capillary tube with blood between the two marked lines. Avoid getting air bubbles trapped in the capillary tube (Figure 24.2h).

11 Properly dispose of all contaminated supplies (Figure 24.2i).

24.6 Step 4: How to perform a rapid HIV test

Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 can be detected by rapid HIV tests. The advantages they offer over other testing technologies is that they can be performed on small amounts of blood, the results are available within minutes, and they can be done in a person’s home or at a health post.

In Ethiopia we use three types of rapid HIV test kits. They are known as:

- KHB (a trade name)

- STAT-PAK (a trade name)

- Uni-gold (a trade name).

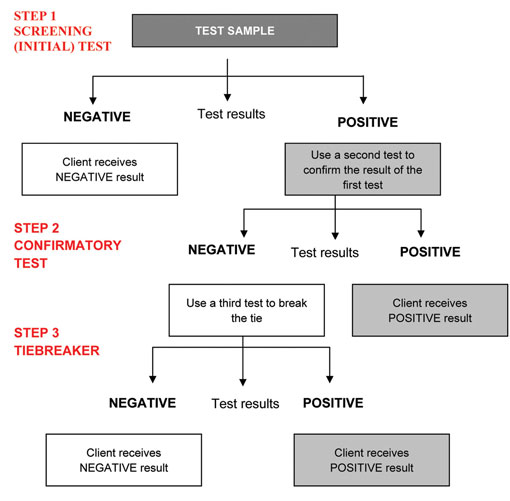

The logical step-by-step procedure for using the three rapid test kits to determine an individual’s HIV status is called the HIV testing algorithm (Figure 24.3).

The algorithm uses three types of tests — the screening test, the confirmatory test, and a tiebreaker. The screening test is the first test in the sequence. The confirmatory test is used to confirm a positive result if the first test is positive. A tiebreaker is the final test which is done when there is a difference between the screening and confirmatory test results. In Ethiopia, we use KHB as a screening test, STAT-PAK as a confirmatory test, and Uni-gold as a tiebreaker.

If a test is non-reactive when using the KHB test kit, we do not need to do another test and we report it as negative — the individual tested is HIV-negative.

If the test is reactive with KHB, we need to perform a second test using STAT-PAK to confirm the result. If the test is also reactive with STAT-PAK, we report it as positive — the individual tested is HIV-positive.

Reactive means the test yielded a positive result. A non-reactive result is a negative result.

If the test is reactive with KHB, but non-reactive with STAT-PAK, we need to do a tiebreaker test (Uni-gold). If the Uni-gold is non-reactive, we report the result as negative. However, if the Uni-gold is reactive, we report the result as positive.

After how many tests do you notify the client that the outcome of the testing process is that he or she is HIV-positive?

You should not report a positive HIV test result after just using one test. At least two different rapid tests have to be reactive before you report a positive result.

The following sections provide guidance on how to conduct a rapid HIV test.

24.6.1 Performing an HIV test using the KHB rapid test kit

First, collect the test items and other necessary laboratory supplies. Remove the KHB device from its packaging, and label it using a code number or a client identification number. The client is the patient or person taking the test. Code numbers should be used to ensure the test is anonymous.

The device has two parts — at the bottom there is a deep circular area where the blood sample is placed (the sample port); at the top there are two areas marked ‘C’ for control and ‘T’ for the test result line.

A photograph of a KHB test is shown in Figure 24.4. The KHB, STAT-PAK and Uni-gold kits have similar structures and parts, though the Uni-gold kit has a different shape.

Collect the specimen using a capillary tube, as described in Section 24.5 of this study session.

Add a drop of whole blood from the capillary tube, enough to cover the sample port of the device (this is shown in Figure 24.5), before adding one drop of running buffer using a pipette. (A running buffer is a liquid that contains reagents and provides optimal conditions for the test to develop).

Now wait for 30 minutes for the test to develop. The control line will be the first to show, and this indicates that the test is working correctly and is valid.

Reading the result of a KHB test

After 30 minutes the test result is ready. Interpretation of the KHB test is straightforward, and examples of real test results are shown in Figure 24.6.

If both the control line and test line are seen, the result is considered to be reactive (top panel of Figure 24.6). If only the control line appears and no test line is seen, the result is considered to be non-reactive (middle panel of Figure 24.6).

If the control line is not seen, the test has not worked correctly (it may have been damaged) and the result is considered to be invalid (bottom panel of Figure 24.6). If the result is invalid, the procedure is repeated using a new KHB device. The result must be recorded on a worksheet, together with any relevant information.

How would you interpret a non-reactive KHB result?

This indicates that the person who supplied the blood is HIV-negative and therefore there is no need to proceed to the STAT-PAK test.

What do you do if you get a reactive result using the KHB device?

If you get a reactive result with the KHB device, you should proceed to the second test, which is STAT-PAK, to confirm the result.

24.6.2 Performing an HIV test using the STAT-PAK rapid test kit

The procedure for this test is very similar to that used for the KHB test. However, there are some differences. The procedure for the STAT-PAK test is outlined below.

First, collect the test items and other necessary laboratory supplies. Remove the STAT-PAK device from its packaging, and label it using a code number or a client identification number.

Like the KHB device, the STAT-PAK also has a sample port and an area where the control and test lines are read.

Collect the specimen using a capillary tube as described earlier in this study session, and place some of the blood on a microscope slide.

Using the special applicator provided with the STAT-PAK kit, collect blood from the microscope slide and then transfer it to the sample port. Now add one drop of running buffer using the bottle of reagent supplied with the kit (these steps are shown in Figure 24.7).

Now wait ten minutes for the test to develop. The control line will be the first to show, and this indicates that the test is working correctly and is valid.

The STAT-PAK test only takes 10 minutes to develop, whereas the KHB test can take up to 30 minutes to produce a result.

Reading the result of a STAT-PAK test

After ten minutes the test result is ready. Interpretation of the STAT-PAK device is the same as for the KHB device, and this is shown in Figure 24.8. If the result is invalid, the procedure is repeated using a new STAT-PAK device. The result must be recorded on a worksheet, together with any relevant information.

How would you interpret the results of a STAT-PAK test?

A reactive result would indicate that the person who supplied the blood is HIV-positive. If the result was non-reactive, you would proceed to the tiebreaker test using the Uni-gold device.

24.6.3 Performing an HIV test using the Uni-gold rapid test kit

The procedure for this test is very similar to that used for the KHB and STAT-PAK tests. However, there are some differences. The procedure for the Uni-gold test is outlined below.

First, collect the test items and other necessary laboratory supplies. Remove the Uni-gold device from its packaging, and label it using a code number or a client identification number. The Uni-gold also has a sample port and an area where the control and test lines are read.

Unlike the other tests, blood is collected from the punctured finger using a pipette and then two drops of blood (60 µl) are placed into the sample port of the Uni-gold device (see Figure 24.9). Two drops of running buffer (60 µl) are then also added to the sample port.

µl means ‘microlitre’.

Now wait for ten minutes (and no longer than twenty minutes) for the test to develop. The control line will be the first to show, and this indicates that the test is working correctly and is valid.

Reading the result of a Uni-gold test

After ten minutes the test result is ready. Interpretation of the Uni-gold device is similar to the other devices, and this is shown in Figure 24.10. If the result is invalid, the procedure is repeated using a new Uni-gold device. The result must be recorded on a worksheet, together with any relevant information.

How would you interpret the result of a Uni-gold test?

A reactive result indicates that the person who supplied the blood is HIV-positive, whereas a non-reactive result indicates that they are HIV-negative.

24.7 Step 5: Delivering an HIV test result, post-test counselling, and referral for treatment

The focus of post-test counselling for people with HIV-positive test results is to provide psychosocial support to help the tested person cope with the emotional impact of the test result, to facilitate (i) access to treatment, (ii) care services, (iii) prevention of transmission, and (iv) disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners.

24.7.1 Delivering the result and post-test counselling when the result is HIV-positive

During post-test counselling, you should cover the following points:

- Inform the person of the result simply and clearly, and give him or her time to consider it. You could ask ‘Are you ready to hear the result?’, allowing the person an opportunity to ask additional questions before you give the result. Most people are ready to hear their result and this should be delivered without undue delay.

- Ensure that the person understands the result. Avoid using technical language such as ‘reactive’ and ‘non-reactive’.

- Allow the person time to ask questions.

- Help the person to cope with emotions arising from the test result. The emotional response to an HIV-positive result can include confusion, anger, denial, sadness, loss, uncertainty, fear of death, shame (embarrassment), fear of stigma and discrimination.

- Discuss any immediate concerns, and assist the person to determine who in their social network may be available and acceptable to offer immediate support.

- Describe follow-up services that are available in the health facility and in the community, focusing on the available treatment, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, and HIV care and support services.

- Provide information on how to prevent transmission of HIV, including provision of male and female condoms and guidance on their use (Study Sessions 25 and 29).

- Provide information on other relevant preventative health measures, such as good nutrition, cotrimoxazole (for prophylactic chemotherapy of opportunistic infections) and, in malarious areas, insecticide-treated bed nets.

- Discuss possible disclosure of the positive result, when and how this may happen, and to whom.

- Encourage and offer referral for testing and counselling of current and former partners, and children who may be at risk.

- Assess the risk of violence or suicide, and discuss possible steps to ensure the physical safety of people with an HIV-positive test result, particularly women.

You should also arrange a specific date and time for a follow-up visit or referral for treatment, care, counselling, support, and other services as appropriate, e.g. tuberculosis screening and treatment, prophylaxis for opportunistic infections, treatment for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), family planning and antenatal care.

24.7.2 Delivering the result and post-test counselling for HIV-negative people

An HIV-negative test result can produce a range of emotional responses, including relief, excitement, or optimism (the result may feel like a new opportunity). The person may also feel confused — they may have perceived themselves as HIV-positive, and they may have an HIV-infected current or former partner.

An important issue to consider when delivering a negative HIV test result is what is termed the window period. The window period refers to the time between HIV infection and the time at which HIV can be detected by available tests. Rapid HIV tests detect anti-HIV antibodies in the blood, but it usually takes about three months from the original HIV infection for the immune system to develop sufficient levels of antibodies against HIV to be detected by these tests. So individuals who are within this window period (i.e. who have been recently infected by HIV) may test negative in a rapid HIV test and yet still be able to transmit the virus. Therefore, you should advise people who may have recently been exposed to HIV (by unprotected sex and/or blood-contaminated products) to have another confirmatory HIV test at least three months after exposure to the virus.

Counselling for individuals with HIV-negative test results should include the following information:

- An explanation of the test result, including information about the window period for the appearance of HIV antibodies, and a recommendation to re-test in case of a recent exposure.

- Basic advice on methods to prevent HIV transmission.

- Provision of male and female condoms, and guidance on their use.

- The health worker and the tested person should then jointly assess whether there is a need for more extensive post-test counselling or additional prevention support, for example, through community-based services.

Summary of Study Session 24

In Study Session 24, you have learned that:

- HIV testing has several benefits — it creates early access to HIV treatment and care, it encourages reduction of high-risk behaviour, it helps people to make lifestyle changes and avoid transmission of the virus to partners; and for those found to be negative, it helps them to develop a plan to remain HIV-negative.

- The barriers to HIV testing can be client-related, healthworker-related and health facility-related.

- There are three different modes of delivering HIV testing and counselling — voluntary counselling and testing (VCT), provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling (PITC), and mandatory testing.

- HIV testing and counselling should respect human rights. Informed consent should be obtained prior to testing. Mandatory HIV testing can be ordered by a court in cases dealing with sexual assault and rape.

- There are five steps in delivering PITC:

Step 1: Recommend HIV testing.

Step 2: Provide brief pre-test information and education on HIV/AIDS, assure confidentiality, and obtain informed consent.

Step 3: Obtain specimen for HIV testing.

Step 4: Perform rapid HIV test.

Step 5: Deliver HIV test result, provide post-test counselling, and refer the patient if necessary.

- The three rapid HIV test kits used in Ethiopia are KHB as a screening test, STAT-PAK as a confirmatory test, and Uni-gold as a tiebreaker test. Testing follows a standard set of procedures as laid out in the HIV testing algorithm.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 24

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 24.1 (tests Learning Outcome 24.1)

Is the statement below true or false. Explain your reasoning.

‘PITC is HIV testing initiated by the client.’

Answer

The statement is false because PITC is HIV testing initiated by the healthworker either in the health facility or at community level.

SAQ 24.2 (tests Learning Outcome 24.2)

Which of the following is not a benefit of HIV testing? Explain why.

A It creates early access to HIV treatment and care.

B It provides an opportunity to reduce high-risk behaviour.

C It helps in preventing transmission of HIV.

D It helps those found to be HIV-negative to practise sex without the need for protection.

Answer

Statement D is not a benefit of HIV testing because individuals found to be HIV-negative should have a plan to remain HIV-negative. They should plan to avoid sexual behaviour and practices that increase the possibility of being exposed to HIV. As part of this plan, they should practise safe sex.

SAQ 24.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 24.1 and 24.3)

Which of the following is not a mode of delivery of HIV counselling and testing that requires the client’s consent? When should this method be applied?

A PITC

B VCT

C Mandatory HIV testing.

Answer

The answer is C. Mandatory HIV testing is only used when requested by a court in rape or other sexual assault cases.

SAQ 24.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 24.4 and 24.6)

Which of the five steps of performing PITC is crucial for linking HIV patients to comprehensive HIV prevention, care, treatment and support services? Explain why.

Answer

It is the fifth step. HIV-positive people may not be linked to these services unless you do proper post-test counselling, referral and follow-up of the referral.

SAQ 24.5 (tests Learning Outcome 24.5)

Is the following statement true or false. Explain your reasoning.

‘We can report a positive HIV test just by doing a KHB rapid test.’

Answer

The statement is false because you have to perform a second test using STAT-PAK before reporting a positive test. A third test using a Uni-gold device may be required if the STAT-PAK test is non-reactive.