Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 22 November 2025, 12:51 PM

Communicable Diseases Module: 30. Providing Palliative Care for People Living with HIV

Study Session 30 Providing Palliative Care for People Living with HIV

Introduction

In this study session you will learn what palliative care means; how to obtain information, grade pain and provide pain relief; how to advise patients on home-based methods for controlling pain; and on home-based and end-of-life care for people living with HIV (PLHIV). You will also learn how to provide psychosocial and nutritional support. In the future you may be involved in providing community-based palliative care services for PLHIV.

Palliative care is care given to chronically ill people to improve their quality of life and that of their families. It involves prevention and relief of suffering, pain and other physical problems, and attention to psychosocial and spiritual issues. Palliative care is also provided for terminally ill patients with conditions such as cancer, heart disease and stroke. The four components of palliative care in Ethiopia which you will learn about in this session are symptom management, including pain management; psychosocial and spiritual support; home-based care, and end-of-life care.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 30

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

30.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQ 30.1)

30.2 Explain what palliative care means, its importance, and its four components. (SAQ 30.1)

30.3 Describe how to provide pain management, with and without medication, and assess when to refer patients for further pain treatment. (SAQs 30.2 and 30.3)

30.4 Describe how to prevent and manage the common symptoms of HIV/AIDS using home-based care. (SAQ 30.3)

30.5 Describe how to provide psychosocial and spiritual care at home for chronically ill people with HIV/AIDS. (SAQ 30.3)

30.6 Describe how to provide preventative home-based care services for bedridden patients with AIDS. (SAQ 30.4)

30.7 Describe how to provide end-of-life care, especially bereavement care. (SAQ 30.5)

30.1 Palliative care and its significance in chronic illness

Note that palliative care does not only mean the terminal care given to people dying from an incurable chronic illness.

Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life for chronically ill patients and their families, by preventing and giving relief for pain and other physical, psychosocial and spiritual problems. It is also an essential part of comprehensive HIV care and support services. Palliative care is provided for patients from the time the chronic disease is diagnosed until the end of life. It regards dying as a normal process, and affirms life. It also offers support to help the patient and family cope during the illness and in the bereavement period, the time of grief due to the loss of a loved one through death.

Palliative care is not only useful for patients with HIV/AIDS, but also for people with chronic communicable and non-communicable diseases who require long-term care at home. It is also important for people with a curable illness with symptoms that last a long period of time (e.g. many months) before they are cured.

Cancer, diabetes, heart disease and chronic lung disease are described in the Non-Communicable Diseases, Emergency Care and Mental Health Module.

Can you think of a curable chronic communicable disease whose patients may benefit from palliative care?

Treatment for tuberculosis may involve long-term care at home.

The palliative care needs of patients increase with time, particularly in a situation where the underlying disease is getting worse rather than better. In areas where patients present late for medical care, the need for palliative care is high. With good treatment and support, palliative care can help many patients live comfortably with a chronic disease for many years. For those who have advanced disease in a terminal phase, palliative care focuses on promoting quality of life by providing good symptom management. This can help patients continue to function and enjoy life at home for as long as possible.

What are the four major components of palliative care in Ethiopia?

They are: symptom management, including pain management, psychosocial and spiritual support, home-based care and end-of-life care.

Below we will discuss each of the four components of palliative care for PLHIV in detail. Remember that these components are inter-related.

30.2 Symptom management, including pain management

In palliative care for PLHIV, the aim is to manage symptoms arising from:

- AIDS itself and associated opportunistic infections, like headaches and other pains, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, weight loss, anxiety, fatigue, depression, skin and mouth problems, neurological disorders, etc.

- the side-effects of antiretroviral drugs to treat HIV disease and chemoprophylactic drugs to treat opportunistic infections.

30.2.1 Management of pain in PLHIV

Pain is one of the most common symptoms in HIV/AIDS patients with advancing disease. If your patients complain of pain, they should be assessed carefully (as described below); severe cases should receive urgent referral for specialist consultation and treatment.

How to assess pain

First, ask the patient ‘Where is the pain?’ and ‘What makes it better or worse?’ ‘What type of pain is it, and what medication (if any) is being taken for the pain?’ Note that pain could result from severe opportunistic infections, and this may need urgent referral to a health centre or hospital.

Secondly, determine the type of pain. Is it a familiar pain (such as bone or mouth pain), or a special and unusual pain (such as shooting nerve pain or muscle spasms)?

Thirdly, check if there is a psychological or spiritual component to the pain. Does it feel worse when the patient is depressed or anxious? Does it feel better when the person is doing something interesting that takes their attention away from the pain?

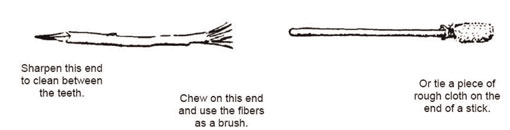

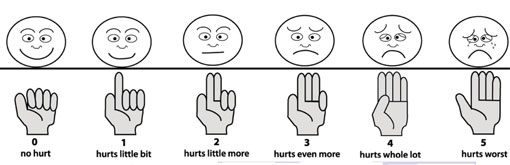

Fourthly, grade the pain from 0 to 5 with the faces chart (especially when working with children), as illustrated in Figure 30.1, or using your hand with different numbers of fingers raised (no fingers being no pain, and five fingers the worst possible pain).

How to manage pain at community level

Manage the pain with paracetamol if it is at grade 1 or grade 2. Paracetamol is the anti-pain medication that you are allowed to give at community level. Refer patients with pain at grades 3, 4 and 5 to the nearest health facility.

Why do you think you should refer patients with grade 3 pain or above?

You should refer such patients quickly because the pain may be indicating severe disease, which needs better diagnosis and management with anti-pain drugs that can only be given by a doctor.

Pain can also be managed without the use of modern medication. Indeed, spiritual and emotional support and counselling should always accompany pain medication. This is because pain can be harder to bear when there is guilt, fear of dying, loneliness, anxiety or depression. Likewise, answering questions and providing information on HIV/AIDS health-related issues is important to relieve fear and anxiety, which in turn makes pain more bearable. The other ways to relieve pain are deep breathing and relaxation techniques (unless the patient has severe mental health problems); or distracting the patient’s attention using music, conversation, or imagining a calm scene.

In your catchment area, how do people treat pain without using modern medication? Give two examples of local pain treatments which are not effective in relieving chronic pain.

Local pain remedies vary in different parts of the country, but you may have thought of tying the painful area with a scarf or other cloth to treat headache or back pain; or burning the skin of the painful area using very hot wooden or metal sticks, sometimes to treat headaches, but mainly for pains in the hands and feet. These treatments are not effective and can make the pain worse. Burning the skin creates a wound that could become infected.

Traditional medication for pain relief may interfere with ARV drugs. Refer patients to the nearest health centre for advice on this topic.

Traditional medication for pain relief may interfere with ARV drugs. Refer patients to the nearest health centre for advice on this topic.

30.2.2 How to manage other common symptoms of HIV/AIDS

Study Session 22 has already described how to manage the adverse side-effects of drugs used to treat HIV disease. In this section we summarise the advice you should give to help someone manage the symptoms of advanced HIV disease.

Nausea and vomiting

![]() Note that persistent vomiting needs medical treatment, and you must refer the patient urgently.

Note that persistent vomiting needs medical treatment, and you must refer the patient urgently.

Advise the sick person to:

- seek locally available foods which he or she likes (tastes may change with illness), and which cause less nausea.

- eat small but frequent locally available foods such as roasted potatoes.

- let the patient drink what he/she likes, e.g. water, tea, ginger drink, etc.

- avoid being near the person who is cooking.

- use effective local remedies for nausea.

- seek help from the health facility if vomiting occurs more than once a day, or if dry tongue, or passing little urine, or abdominal pain is present.

Diarrhoea

Advise the sick person to:

- drink fluids frequently in small amounts, preferably oral rehydration solution (ORS). If ORS is not available, give home-made fluids such as rice soup, porridge, weak tea, water (with food), and other soups.

- avoid sweet drinks, milk, coffee, strong tea and alcohol.

- continue eating. For persistent diarrhoea, suggest a supportive diet, like carrot soup, which helps to replace vitamins and minerals, soothes the bowels and stimulates the appetite. Other foods that may help to reduce diarrhoea are rice and potatoes.

- avoid eating raw foods (like bananas and tomatoes), cold foods, high-fibre foods, and foods containing fat. Tell them to avoid milk and cheese, but yogurt is better tolerated.

Refer patients with diarrhoea to a health centre if:

- there is vomiting with fever.

- blood is seen in the stool.

- diarrhoea continues for more than five days and the patient becomes even weaker.

- there is broken skin around the rectal area.

30.3 Psychosocial and spiritual support

Psychosocial support is a fundamental part of palliative care, and includes a range of interventions that enable the person who needs palliative care, and their caregivers and families, to cope with the overwhelming feelings that result from their experiences with long-term disease and the threat of death. Providing psychosocial support may include supporting their self-esteem (self-respect or confidence in oneself), helping them to adapt to the illness and its consequences, and helping them to improve their communication with each other and with you, and their social functioning and their relationships.

Spiritual support involves taking into account not only the patient’s religious or faith beliefs and practices, but also their understanding of the purpose and meaning of life.

30.3.1 Support for the patient

PLHIV often feel unhappy, and even depressed at times. They will be calmer if they accept the illness as much as they are able to, and realise that it is possible to live a healthy life and be productive if they take their medication correctly. You can help by introducing them to a nearby PLHIV association, or a community-based organisation which provides support to PLHIV (if available).

Psychosocial support for PLHIV should also address practical aspects of care, such as finances, housing, and assistance with daily living. Regarding spiritual support, you may want to discuss spiritual beliefs, cultural issues and personal values. The following tips will help you to provide spiritual support to patients:

- Be prepared to discuss spiritual matters if patients would like to. Some useful questions you may use are:

- What is important to you in life?

- What helps you through difficult times?

- Do you have a faith that helps you make sense of life?

- Do you ever pray?

- Learn to listen with empathy.

- Understand reactions to the losses in their life (the different stages of grief).

- Be prepared to ‘absorb’ some reactions, for example, patients may express anger towards you, but this is only because they are afraid and anxious.

- Connect the patient’s needs with a spiritual counsellor or religious leader, according to their religion and wishes.

- Do not impose your own views. If you share religious beliefs, praying together may be appropriate.

- For some patients, it is better to talk about the meaning of their life, rather than directly about spirituality or religion.

30.3.2 Support for the caregivers

Caregivers in the family frequently feel anxious or depressed, or have problems with sleeping, as the person they care for comes closer to the end of life. You can encourage caregivers to share their feelings with you by asking questions about their perception of the patient’s illness and its impact on their life. Mild psychological distress (mental suffering caused by grief, anxiety or unhappiness) is usually relieved by emotional support from health workers who have effective communication skills. By explaining the patient’s physical and psychological symptoms, and challenging false beliefs about death and dying, you can bring a reasonable hope to caregivers and to the patient, and reduce the sense of isolation they may feel. Empower the family to provide care by explaining that as human beings, we know how to care for each other. Reassure them that they already have much of the capacity needed, and that you can give them more information and support their skills.

30.4 Home-based care

Home-based care is the care of people affected by HIV/AIDS, cancer, and other chronic diseases, that is based in the patient’s home. In the case of HIV/ AIDS, the need for home-based care largely corresponds to late HIV disease (stage 3) or AIDS (stage 4). Home-based care involves the community (depending on available resources) and healthcare workers in supporting the care provided by the family at home. Patients receiving home-based care may have been treated earlier in hospital, and may continue to receive some care from the health facility nearest to their home. Some of the preventative home-based care services for PLHIV are described below.

30.4.1 Support for oral hygiene

For patients able to self-care, advise them that twice a day they should use a soft toothbrush (or a piece of soft stick or clean cloth if a toothbrush cannot be obtained; see Figure 30.2) to gently brush their teeth, tongue, palate and gums to remove debris. Use toothpaste if affordable and available. Rinse the mouth with diluted salt water after eating and at bedtime (usually three to four times daily). For patients who cannot do this for themselves, tell the caregivers to provide oral care to the patient two to three times every day, as described above.

30.4.2 Preventing bedsores in bedridden patients

A bedridden patient is one who is too sick to get out of bed at all, or only for short periods.

To prevent bedsores, you should do the following:

- Help the patient to sit out in a chair from time to time if possible. (We will show you how to do this later.)

- Lift the patient up off the bed slowly — do not drag the person’s body as it breaks the skin. Ask a family member to help you — two people can do this much more easily, with less discomfort for the patient. (Later we will show you how to do it if you are on your own.)

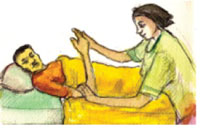

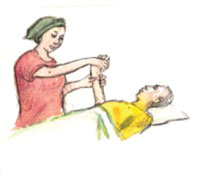

Figure 30.3 A caregiver and Health Extension Practitioner changing the body position of a bedridden patient.

Figure 30.3 A caregiver and Health Extension Practitioner changing the body position of a bedridden patient. - Encourage the patient to move around in the bed as much as they are able to. If they cannot move, change their position on the bed frequently, if possible every one or two hours (Figure 30.3). Use pillows or cushions beside the patient to help them keep the new position.

- Keep the bed sheets clean and dry. Put extra soft material, such as a soft cotton towel, under the patient.

- Look for damaged skin (change of colour) on the patient’s back, shoulders and hips every day. Massage the back and hips, elbows, heels and ankles every day with petroleum jelly if available, or any other soothing cream or oil. This helps to prevent ‘bed sores’ from developing.

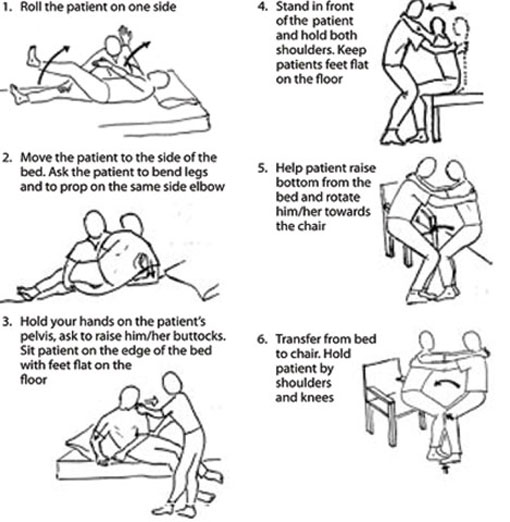

30.4.3 Moving a bedridden patient

You or the patient’s caregiver need to know how to move a bedridden patient if you are on your own. If the patient is unconscious or unable to cooperate, it is better to have two people to help with moving the patient, but this is not always possible. When transferring the patient from the bed to a chair, use the procedures shown in Figure 30.4. This will help to protect you and the patient from strain and injury.

30.4.4 Hygienic care of the body

Remember to provide privacy for the patient during bathing, which is necessary every day to give hygienic care of the body and skin. Show the caregivers how to follow these procedures:

- Dry the skin gently after washing with a soft clean towel or cloth.

- Oil the skin with cream or body oil if available; if not, you can use a vegetable oil.

- Use plastic sheets under the bed sheets to keep the bed dry, if the patient cannot control urine or faeces.

- If there is leakage of urine or stools, protect the patient’s skin with petroleum jelly applied around the genital area, anus, back, hips, ankles and elbows.

- Support the sick person over the container when passing urine or stools to avoid injury and wetting the bed.

30.4.5 Preventing stiff joints and muscles

Figures 30.5 to 30.8 illustrate some of the ways you and the caregivers can help a patient to exercise their joints and muscles to prevent stiffness and contraction due to pain, or lying still for a long time.

30.5 End-of-life care

The end of life is the terminal phase in the advanced stages of disease when the patient is expected to die in a matter of days. End-of-life care aims to recognise that life and death are normal. It neither hastens nor postpones death, it achieves the best quality of life in the time remaining, and provides good control of pain and other symptoms. It helps the dying patient and loved ones to adjust to the many losses they face, and ensures a dignified death with minimal distress. It also provides support and help for the family to cope with bereavement.

A major challenge you will face is to decide when the patient has reached the terminal phase of the illness and needs end-of-life care. A terminal illness is one for which no cure is available, and from which the patient is expected to die relatively soon.

Patients with terminal illness are usually treated with palliative care at home rather than in hospital.

Once a patient has been declared terminally ill, management of some conditions will change, and some medications may stop altogether. You may need to consult your supervisor or a nurse to help you decide when an HIV/AIDS patient is terminally ill.

30.5.1 Preparing for death

Encourage communication within the family. Discuss worrying issues and offer practical support in resolving concerns such as making a will, custody of children, family support, future school fees, old quarrels, or funeral costs.

Tell the patient that he/she is loved and will be remembered. Talk about death if the person wishes to, but keep in mind cultural taboos if you are not in a close relationship with the patient. Help the patient accept his/her own death. Ask him/her how they wish to die, for example with pastoral or religious leaders present, or with family only.

Make sure that what the patient wants is always respected.

Respond sensitively to the patient’s grief reaction to realising they are dying. This may include denial, disbelief, confusion, shock, sadness, anger, humiliation, despair, guilt, and finally acceptance. Make sure the patient gets help with feelings of guilt or regret. Keep communication open — if the dying person does not want to talk, ask ‘Would you like to talk now or later?’

30.5.2 A checklist for end-of-life care

Here are some points for you to bear in mind when you are caring for a person at the end of his/her life.

Presence

- Be present with compassion.

- Visit regularly.

- Move slowly and quietly.

Caring and comfort

- Moisten the lips, mouth and eyes. Offer sips of liquid to drink.

- Keep the patient clean and dry, and prepare for leakage from the bowel (faeces) and bladder (urine).

- Provide physical contact by light touch. Hold the person’s hand, listen and converse if they want to talk.

- Reassure the patient that eating less is alright; don’t make them eat if they don’t want to.

Medication and symptom control

- Only give essential medication — anti-diarrhoeal remedies, and paracetamol to treat pain or fever. Make sure pain is controlled.

- Help the patient control other symptoms by ensuring that medical treatment prescribed by the doctor is taken at the right times and in the right dosages.

- Skin care requires the patient to be turned every two hours, or more frequently, as already described in Section 30.4.2.

30.5.3 Recognising signs of death

When a patient is very close to death, watch for these signs:

- Decreased social interaction — the person sleeps more, they may act or speak with confusion when awake, and they may slip into a coma (become unconscious).

- Decreased food and fluid intake — the person no longer feels hunger or thirst.

- Decreased urine and bowel movements, or incontinence.

- Respiratory changes — irregular breathing or ‘death rattle’ (a rough gurgling noise that sometimes comes from the throat when a person is close to death, caused by breath passing through mucus).

- Circulatory changes — the hands and feet may feel cold and appear greyish or purple as the heart slows and can no longer pump blood to these extremities. You may notice a decreased heart rate and blood pressure.

When the patient dies, you can confirm death by checking that:

- breathing stops completely.

- heartbeat and pulse stop completely.

- the person is totally unresponsive to shaking or shouting.

- the eyes are fixed in one direction, with eyelids open or closed.

- the skin changes tone and becomes pale.

30.5.4 Bereavement counselling

Provide bereavement counselling for the patient before death (as described earlier) and for the family after death of their beloved. They may also feel denial, disbelief, confusion, shock, sadness, anger, humiliation, despair and guilt about the dead person and the care they received before death. Help the family accept the death of the loved one. Share the sorrow — encourage them to talk and share their good memories. Do not offer false comfort — offer simple expressions and take time to listen.

Remember to offer practical help. For example, try to see if friends or neighbours can help with cooking, cleaning, running errands, child care, etc. for a few days after the death. This can help in the midst of grieving. Ask the family if they can afford the funeral costs and future school fees, and help in finding a solution if possible.

Encourage patience — it can take a long time to recover from a major loss. Say that they will never stop missing their loved one, but the pain will ease and allow them to go on with life.

Summary of Study Session 30

In Study Session 30, you have learned that:

- Palliative care is an essential part of comprehensive care and support for PLHIV. It is care given to chronically ill patients to improve their quality of life and that of their families by preventing and relieving suffering.

- The four components of palliative care for PLHIV in Ethiopia are symptom management, including pain management, psychosocial and spiritual support, home-based care and end-of-life care.

- Pain is one of the most common symptoms in HIV/AIDS. If patients complain of pain, they should be assessed carefully, and in severe cases urgent referral and consultation is needed.

- Common but mild symptoms of HIV/AIDS, like nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, can be managed at home by giving advice on diet, fluids, hygiene, skin care and other home-based interventions.

- Chronically ill patients who are bedridden need oral, skin and body care, with frequent repositioning to prevent development of bed sores. Simple exercises/movements can ease stiffness of joints and muscles.

- Psychosocial support and bereavement counselling is an essential part of palliative and end-of-life care. It includes communication, caring and practical skills that enable individuals and families to cope with the often overwhelming feelings that result from their experiences with long-term disease and death.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 30

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the questions below. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 30.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 30.1 and 30.2)

Which of the following statements regarding palliative care for PLHIV is false? In each case, explain what is incorrect.

A Palliative care is only given to patients who are near to death.

B Palliative care is provided only to PLHIV because HIV/AIDS is not curable.

C Palliative care is an essential part of care for patients with cancers.

D Patients with chronic illnesses like diabetes or stroke may need palliative care.

E Palliative care includes prevention and relief of suffering, pain and other physical problems, as well as attention to psychosocial and spiritual issues.

Answer

C, D and E are true.

A is false. Palliative care is not terminal care (care given to dying patients only); it is the care provided to patients with a chronic illness, from the time the disease is diagnosed until the end of life. It regards dying as a normal process, and affirms life. This is well described in statement E, which is true.

B is false. Palliative care is also needed for patients with other non-curable chronic diseases like cancer, diabetes and strokes, as described in the true statements C and D.

SAQ 30.2 (tests Learning Outcome 30.3)

Is the following statement true or false? Explain your reasoning.

‘Relieving pain is not a routine part of palliative care, since it is not treating the chronic disease that caused the pain.’

Answer

The statement is false. Even though the disease causing the pain is not curable, we have to manage pain properly. The reason for doing this is because pain makes patients suffer a lot, which in turn affects their quality of life. Treating pain is relieving patients from this suffering, and hence giving them a better quality of life. Pain management should be an integral part of managing non-curable chronic illnesses.

Read Case Study 30.1, and then answer the questions that follow it.

Case Study 30.1 Ato Aytenfisu’s story

Ato Aytenfisu is a 45-year-old man living with HIV who started antiretroviral medication two weeks ago. During your home visit you find that he is feeling ill. He has had a mild headache and watery diarrhoea two to three times per day for the past four days. He looks very unhappy. He has no vomiting, fever, neck stiffness or other symptoms.

SAQ 30.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 30.3, 30.4 and 30.5)

- a.What should you do first for Ato Aytenfisu?

- b.What should you do regarding the headache?

- c.What should you give him for the diarrhoea? What advice should you give him about managing the diarrhoea?

- d.How can you help him relieve his unhappiness?

Answer

- a.First, you reassure Ato Aytenfisu that his symptoms could be adverse side-effects from the ARV drugs he is taking, and that he will be alright after some days. But make sure he knows that if the headache and diarrhoea get worse, or if blood is seen in stools, he should visit the nearby health centre as soon as possible.

- b.For the headache you should give him paracetamol, as it is a mild symptom.

- c.Regarding the diarrhoea, you should give him oral rehydration solution (ORS) and advise him to drink it frequently in small amounts. If there is no ORS, you can advise him to take home-made fluids such as rice soup, weak tea or just plain water, but avoid taking sweet drinks, milk, strong tea or alcohol. Tell him to continue eating as usual. If the diarrhoea worsens, he should go to the nearby health centre for better management.

- d.With respect to the unhappiness, you could advise him to accept the illness as much as he can, and that it is possible to live a healthy life and be productive if he takes the antiretroviral drugs correctly. If available, you need to introduce him to a nearby PLHIV association, or a community-based organisation which provides support to PLHIV. You also need to arrange a follow-up visit.

SAQ 30.4 (tests Learning Outcome 30.6)

Which of the following is not part of the preventative home-based care you will give to bedridden patients with AIDS? Explain why it is not included.

A Frequent repositioning of a bedridden patient and skin care to prevent bed sores

B Providing oral care

C Providing hygienic care of the body

D Exercising the joints to prevent muscle stiffness and contraction

E Treating infection of the lungs.

Answer

E (treating infection of the lungs) is not part of preventative home-based care for bedridden patients. First, it is a treatment, not palliative care. Secondly, if the patient develops a lung infection, he/she has to be referred to a nearby health facility for specialist treatment as soon as possible. All the other statements (A to D) are part of preventative home-based care for bedridden patients.

SAQ 30.5 (tests Learning Outcome 30.7)

Is the following statement true or false? Explain your reasoning.

‘Since terminally ill patients will die soon, it is a waste of a health worker’s time to provide them with end-of-life care.’

Answer

This statement is absolutely false, because end-of-life care is very important for patients with a terminal illness. Indeed, it helps us to recognise that life and death are normal events. It helps the dying patient and loved ones to adjust to the many losses they face, and tries to ensure that a dignified death occurs with minimal distress.