Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 8:18 AM

Communicable Diseases Module: 37. Other Vector-Borne Diseases of Public Health Importance

Study Session 37 Other Vector-Borne Diseases of Public Health Importance

Introduction

Three important vector-borne diseases have been discussed previously in this Module: malaria in Study Sessions 5–12 and relapsing fever and typhus in Study Session 36. In this study session, you will learn the causes, modes of transmission, clinical manifestations, prevention and control of four other vector-borne diseases of public health importance in Ethiopia. They are schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis. A better understanding of these diseases will help you to identify patients and refer them quickly to a health centre or hospital for specialist treatment.

You will also learn about the health education messages that you need to communicate to members of your community, so they can reduce their exposure to the vectors of these diseases and apply appropriate prevention measures. As you will see in this study session, prevention of all of these diseases includes controlling the vectors with chemicals and/or environmental management, using personal protective clothing or bed nets to reduce exposure to the vectors, and rapid case detection and referral for treatment. Early treatment prevents serious complications and can save lives, and it also reduces the reservoir of infectious agents in the human population.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 37

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

37.1 Define and use correctly all of the key words printed in bold. (SAQs 37.1 to 37.5)

37.2 Identify the vectors and modes of transmission of schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis. (SAQs 37.1, 37.2 and 37.3)

37.3 Describe the distribution and impact of schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis in Ethiopia. (SAQs 37.1, 37.3, 37.4 and 37.5)

37.4 Describe the symptoms of schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis, and how you would diagnose and refer cases to a higher level health facility. (SAQs 37.3 and 37.4)

37.5 Describe how you would apply prevention and control measures against schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis. (SAQs 37.1, 37.3 and 37.5)

37.1 Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis is pronounced ‘shy-stoh-soh-my-assis’. It is described as chronic because the symptoms develop gradually, become progressively more serious, and last for a long time unless treatment is given.

Schistosomiasis is a chronic communicable disease caused by parasitic flatworms (also known as trematodes, or blood flukes), which affect the blood vessels in the intestines or in the urinary tract of infected people. In some places, the disease is known by its alternative name – bilharzia. Two species of Schistosoma parasites are common in Ethiopia: Schistosoma mansoni (Figure 37.1) which causes disease mainly in the intestines, and Schistosoma haematobium, which causes disease mainly in the bladder and sometimes also in other parts of the urinary tract such as the kidneys.

The WHO estimates that more than 207 million people worldwide are infected with Schistosoma parasites – and 85% of them are in Africa. Approximately 200,000 people die every year in Africa as a result of the complications caused by these parasites. Rural communities living near water bodies such as rivers, lakes and dams may be highly affected by the disease, because the worms have a complex lifecycle in which they spend part of their development living in freshwater snails. You will learn more about their lifecycle later in this section. First, as a Health Extension Practitioner, you need to know where the disease is common in Ethiopia.

37.1.1 Where is schistosomiasis common in Ethiopia?

Schistosoma mansoni is widespread in several parts of Ethiopia, usually at an altitude of between 1,200 to 2,000 metres above sea level. Some of the common places include Ziway (Figure 37.2), Hawassa, Bishoftu, Wonji, Haromaya, Jimma, Bahir Dar and some places in Gojam, Dessie and Tigray. In many of these locations, more than 60% of schoolchildren are infected with Schistosoma mansoni. A high burden of the disease in children has severe adverse effects on their growth and performance at school.

Schistosoma haematobium is limited to some lowland areas, including the swampy land and floodplains of the Awash and Wabe Shebele valleys and along the Ethiopian–Sudan border.

37.1.2 Mode of transmission of schistosomiasis

Let us now focus on the mode of transmission of schistosomiasis. The major reservoirs of Schistosoma parasites are infected humans (the primary hosts) and freshwater snails (the intermediate hosts).

What do you understand about the term reservoir in the context of communicable diseases? (Think back to Study Session 1 of this Module.)

A reservoir is any location where infectious agents live before they infect new human hosts, and which is important for the survival of the disease-causing organism. Reservoirs can be living (e.g. infected humans or other animals, such as dogs, cows, insects or snails), or non-living things in the environment (e.g. water, food).

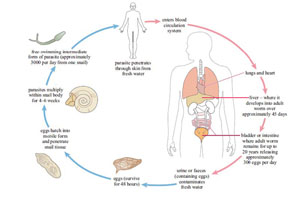

Figure 37.3 shows how Schistosoma parasites are transmitted from infected people to new human hosts, via the intermediate hosts – freshwater snails. Figure 37.4 shows the lifecycle of the parasites in more detail, highlighting the immature forms that can be found in the water.

The immature form of the parasite penetrates the skin of a new host when he or she is swimming, washing or standing in infected water. They pass to the liver, where they mature into adult worms. Male and female adult worms mate (look back at Figure 37.1) and deposit their eggs in the blood vessels of either the intestine (Schistosoma mansoni) or bladder (Schistosoma haematobium). The eggs pass out into the water in either the faeces or urine, to continue the infection cycle.

37.1.3 Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of schistosomiasis

The infected person’s immune system reacts against the parasites’ eggs in their blood vessels, which are recognised as ‘foreign bodies’. The immune reaction causes an acute inflammation around the eggs, which can lead to chronic symptoms (see Box 37.1). Note that the clinical manifestations of schistosomiasis are mainly related to the immune response against the eggs in the intestine or bladder – the symptoms are not due to the worms themselves. The adults can survive in the person’s body for up to 20 years, releasing around 300 eggs every day.

Box 37.1 Clinical manifestations of schistosomiasis

- Dermatitis (itching) where a parasite has penetrated the person’s skin. This so-called ‘swimmer's itch’ occurs most often with Schistosoma mansoni, manifesting two or three days after invasion as an itchy rash on the affected areas of the skin.

- The main symptoms of Schistosoma mansoni infection of the intestines are abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea. A blood test usually reveals signs of anaemia and the abdomen may be swollen due to enlargement of the liver. If the infection remains untreated it can lead to permanent liver damage in advanced cases.

- The main symptoms of Schistosoma haematobium infection of the bladder are pain during urination, frequent need to urinate, and blood in the urine. If the infection remains untreated it can lead to chronic bladder diseases, including cancer, and permanent kidney damage. It may also lead to infertility in men, and pain during sexual intercourse and vaginal bleeding in women.

The clinical manifestations (described above) should lead you to suspect cases of schistosomiasis. Asking children if they have seen any blood in their urine is an important way of detecting whether Schistosoma haematobium is common in the area. The diagnosis of schistosomiasis is confirmed in a laboratory by direct observation of the parasite eggs in samples of faeces or urine examined under the microscope (Figure 37.5).

37.1.4 Prevention and control of schistosomiasis

You will meet these prevention and control categories again when we discuss the other vector-borne diseases later in this study session.

Several prevention and control strategies should be integrated to reduce the burden of schistosomiasis. You have an important role as a Health Extension Practitioner to teach community members in affected areas how to apply the major prevention and control measures, which can be described in five general categories:

- Integrated vector control (IVC) measures, aimed at reducing the number of vectors; in areas affected by schistosomiasis, these measures involve using the chemical ‘Endod’ to kill the snails, and environmental management to destroy snail habitats by improving irrigation and farming practices; this could involve removing vegetation and draining and filling swampy areas or shallow pools wherever possible.

- Parasite control measures, aimed at reducing the number of parasites, e.g. treating water for washing with chlorine or iodine to kill the eggs and immature Schistosoma organisms.

- Personal protection against exposure to the parasites, e.g. farmers, fishermen and others who have to stand in infected water should wear rubber boots to protect their skin from penetration by the swimming forms of the Schistosoma parasites.

- Rapid case detection and referral to the nearest health centre for effective treatment; the drug used to treat schistosomiasis is called praziquantel, which is administered orally at a dosage of 40–60 mg per kg of body weight, given in two or three doses over a single day. You are not expected to prescribe praziquantel, which must be given at the health centre.

- Education in the community about the causes and modes of transmission of schistosomiasis.

What actions would you educate community members to take to protect themselves and their children from schistosomiasis?

In particular, you should encourage people to build and use latrines and avoid urinating or defaecating in water, in order to reduce contamination by Schistosoma eggs. Also they should wear protective clothing when standing in infected water, and seek early diagnosis and treatment for any suspected cases.

37.2 Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a chronic parasitic disease, which exists in two forms: visceral leishmaniasis (also known as kala-azar), which affects the internal organs such as the liver and spleen, and cutaneous leishmaniasis, which affects the skin. The infectious agents are protozoa (single-celled organisms, Figure 37.6). There are four major species of Leishmania protozoa in Ethiopia:

Leishmaniasis is pronounced ‘lye-sh-man-eye-assis’. Visceral is pronounced ‘viss-urr-al’ and cutaneous is pronounced ‘kute-ay-nee-ous’.

- Leishmania donovani, which causes visceral leishmaniasis

- Leishmania aethiopica, Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica, all of which cause cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Around 12 million people in 88 countries around the world are currently thought to be infected with Leishmania parasites and the WHO estimates that one to two million new cases occur each year. The vectors (and intermediate hosts) for these parasites are sandflies. The lifecycle will be described later in this section.

37.2.1 Where is leishmaniasis common in Ethiopia?

During your work in the community, you should know the common places where leishmaniasis is present. Visceral leishmaniasis affecting the internal abdominal organs such as the liver and spleen is widely distributed in the lowlands of Ethiopia. Important endemic locations include Konso woredas (Lake Abaya and Segen Valleys), the Lower Omo plains, the Metama and Humera plains and Adiss Zemen. Cutaneous leishmaniasis occurs in Meta-Abo, Sebeta, Kutaber in Wello, and in some places in South West Ethiopia such as Jimma Zone.

37.2.2 Mode of transmission of leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is transmitted through the bite of female phlebotomine sandflies (Figure 37.7), which bite humans and some animals, and take blood meals to feed the development of their eggs. Phlebotomine means ‘blood-sucking’ and is pronounced ‘fleb-otto-meen’. There are about 30 species of sandflies that can transmit Leishmania parasites to humans found throughout the tropical and temperate regions of the world. The females lay their eggs in many locations, including the burrows of rodents, old tree bark, cracks in buildings and rubbish heaps – anywhere that is warm and humid enough for their eggs to develop into flies.

When sandflies take blood meals from an infected person, they also become infected with the protozoa that cause leishmaniasis. The protozoa develop inside the sandfly and are passed on when the sandfly takes a blood meal from a healthy person. The Leishmania protozoa multiply inside the white blood cells of the healthy person and cause disease (Figure 37.8).

37.2.3 Clinical manifestation and diagnosis of leishmaniasis

The clinical presentation of the two forms of leishmaniasis are very different. Cutaneous leishmaniasis normally produces skin ulcers on the exposed parts of the body such as the face, arms and legs (Figure 37.9). The disease can produce a large number of ulcers – sometimes up to 200 – which may result in physical disability (e.g. in using the hands). The visible ulcers are a source of social stigma, which can leave the patient suffering mental distress and rejection in their community.

![]() If you suspect a case of visceral leismaniasis, the patient should be immediately referred to a higher health facility.

If you suspect a case of visceral leismaniasis, the patient should be immediately referred to a higher health facility.

Visceral leishmaniasis (also known as kala azar, which means black fever in Hindu) is a life-threatening disease characterised by irregular episodes of fever, rapid and extensive weight loss, huge swelling of the spleen and liver (Figure 37.10), and anaemia. If left untreated, up to 100% of patients die within two years of infection. For this reason, visceral leishmaniasis is said to have a high case-fatality rate.

You can identify patients with leishmaniasis by the clinical manifestations of the disease. For confirmation of the diagnosis, laboratory investigations should be done in health centres or hospitals, where the protozoan parasites can be detected in blood smears viewed with a microscope (look back at Figure 37.6).

37.2.4 Prevention and control of leishmaniasis

Several prevention and control measures are available for leishmaniasis. The general principles will already be familiar to you from the earlier discussion of schistosomiasis.

- Integrated vector control (IVC) measures, aimed at reducing the numbers of sandflies by indoor residual spraying of the inside and outside walls of houses, doorways, animal houses, and possible breeding sites of the sandflies (Figure 37.11); use of insecticide treated bed nets (ITNs) for sleeping under at night; and environmental management to reduce the breeding sites of sandflies.

- Rapid case detection and referral to the nearest health centre or hospital prevents the transmission of the parasite to others. Cases of leishmaniasis will be treated using intravenous or intramuscular drugs such as pentostam or amphotericin B. You cannot prescribe these drugs, which must be given under medical supervision.

- Investigate and control epidemics in epidemic-prone areas: early identification and management of epidemics of leishmaniasis helps to control the disease from spreading to the wider population.

- Education in the community about the causes and modes of transmission of leishmaniasis.

What actions would you educate community members to take to protect themselves and their children from leishmaniasis?

You would encourage them to use ITNs at night and not to sleep unprotected out of doors, so as to avoid sandfly bites; they should welcome spraying teams to treat their houses with insecticide, and eliminate rubbish heaps and other locations where sandflies like to lay their eggs. They should seek early diagnosis and treatment of any suspected cases.

37.3 Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis is pronounced ‘onk-oh-serk-eye-assis’.

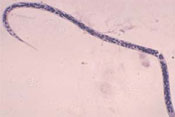

Onchocerciasis is a parasitic vector-borne disease caused by a worm that affects the skin, lymph nodes and the eyes of infected people. It is also called river blindness. The WHO estimates that worldwide there are about 500,000 people who are blind due to onchocerciasis. The disease is caused by a tiny worm called Onchocerca volvulus (Figure 37.12), which is transmitted from person to person in the bite of blackflies.

37.3.1 Where is onchocerciasis common in Ethiopia?

Onchocerciasis is found in the western part of Ethiopia, where there are many rapidly flowing rivers and streams, with vegetation along the banks that provide good habitats for the blackflies that transmit the parasite. The most affected areas include Keffa, Illubabor, Gambella and Wollega. Cases of onchocerciasis have been also reported from Pawe, Humera and Metema.

37.3.2 Mode of transmission of onchocerciasis

The parasites that cause onchocerciasis are transmitted from human to human through the bites of blackflies, which belong to Simulum species (Figure 37.13). Blackflies breed in fast-flowing rivers and streams, with good vegetation nearby. Unlike mosquitoes and sandflies, they bite during the day when people are active in the area.

What type of water does the blackfly need to breed? How does this differ from the water required by the mosquito vectors of malaria?

Blackflies need fast-running water to breed, unlike Anopheles mosquitoes, which breed in shallow stagnant water collections.

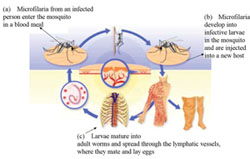

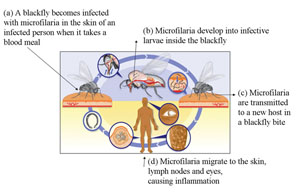

The adult worms mate in the infected person, and the eggs hatch into microscopic worms called microfilaria, which burrow through the body tissues. The person’s immune system attacks the microfilaria, causing inflammation and damage in the surrounding tissues. Sight defects and eventually blindness develops when the microfilaria are embedded in the person’s eye. When a female blackfly bites an infected person during a blood meal, the microfilaria are transferred from the person to the fly (Figure 37.14a). Over the course of one to three weeks, the microfilaria develop inside the blackfly to form infective larvae (Figure 37.14b). These are then passed on to other people when the blackfly takes another blood meal (Figure 37.14c). The microfilaria migrate to the skin, lymph nodes and eyes of the infected person, causing inflammation and tissue damage.

In the human host, the larvae migrate into the skin, and nodules (swellings) form around them. They slowly mature into adult worms, which can live for 15 years in the human body. After mating, the female worm releases around 1,000 microfilaria a day into the surrounding tissue. Microfilaria live for one to two years, moving around the body. When they die, they cause an inflammatory response which leads to the clinical manifestations and complications such as blindness.

37.3.3 Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of onchocerciasis

The clinical manifestations of onchocerciasis are the result of inflammation against the dead microfilaria. The most common clinical manifestations include skin rashes, lesions, intense itching, loss of the colour of the skin, and nodule formation (Figure 37.15a). Microfilaria also migrate to the eye, and causes scarring of the cornea (the covering of the eyeball), which leads to sight defects and ultimately blindness (Figure 37.15b).

The itching and disfiguring nodules and blindness are sources of great distress to patients, who may be stigmatised and rejected by their communities.

Diagnosis of onchocerciasis is made by clinical examination. If you suspect that a patient may be infected, you should make a referral for laboratory confirmation and treatment. Microscopic investigation of a skin snip (taking samples from the skin) can identify the microfilaria and confirm the diagnosis.

37.3.4 Prevention and control of onchocerciasis

The WHO believes that onchocerciasis can be eliminated through the application of effective prevention and control methods, which are summarised below:

- Integrated vector control measures to reduce the population of blackflies, through application of insecticides in vegetation where vectors breed, and environmental management to reduce vegetation around fast-flowing rivers where people live.

- Personal protective clothing to avoid the bite of blackflies by covering exposed skin with clothing and wearing headgear in endemic areas.

- Community-directed mass drug administration (MDA) with ivermectin, i.e. mass drug treatment of everyone in communities where the diseases is endemic with the drug ivermectin, which kills the microfilaria, every 6 to 12 months (Figure 37.16). This is the most successful intervention at community level. Community members fully participate in the programme and the drugs are delivered by trained village drug distributors, supervised by Health Extension Workers and Practitioners like you. Community-directed MDA is being implemented in endemic areas of Ethiopia such as Pawe, Jimma, Illubabor and Keffa.

Figure 37.16 Mass drug administration with ivermectin successfully prevents onchocerciasis in affected communities. (Photo: WHO TDR Image Library, image 9703979/Crump)

Figure 37.16 Mass drug administration with ivermectin successfully prevents onchocerciasis in affected communities. (Photo: WHO TDR Image Library, image 9703979/Crump) - Rapid case detection and referral, particularly for complicated cases involving sight loss

- Education in the community about the causes, mode of transmission and prevention measures against onchocerciasis (Figure 37.17). Encouraging acceptance of the mass drug administration programme is an important health education message that you can deliver in affected communities.

37.4 Lymphatic filariasis

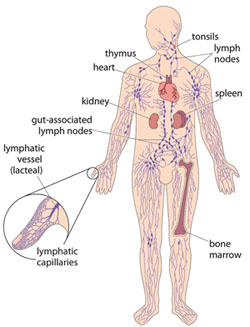

In this final section, you will learn about the definition, mode of transmission, clinical manifestations, and methods of prevention and control of lymphatic filariasis. It is also known as elephantiasis because of its effects on the legs of infected people. Lymphatic filariasis is a parasitic disease caused by a worm that invades the lymphatic system – the network of vessels that exists throughout the body, connecting the lymph nodes, spleen and other organs, and where white blood cells are primarily found (Figure 37.18).

The WHO estimates that over 120 million people worldwide are currently infected with the worm (species name Wuchereria bancrofti, Figure 37.19) which is responsible for 90% of all cases.

37.4.1 Where is lymphatic filariasis common in Ethiopia?

Like onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis is common in western Ethiopia, such as Illubabor, Keffa, Jimma, Wollega, Gambella and Pawe. Though the disease is not fatal, it is responsible for considerable disability and distress, causing social stigma among men, women and children. You will learn more about the social consequences of lymphatic filariasis and a non-infectious cause of swelling in the legs (podoconiosis) in Study Session 39.

37.4.2 Mode of transmission of lymphatic filariasis

The parasites that cause lymphatic filariasis are transmitted from human to human through the bites of Culex and Anopheles mosquitoes. The female mosquitoes take the microscopic forms of the parasitic worm (microfilaria) from an infected person during a blood meal (Figure 37.20a). The microfilaria develop into larvae, and when the mosquito feeds on another person, the larvae enter the skin punctured by the mosquito bite (Figure 37.20b). The larvae travel via the lymphatic vessels, where they develop into adult worms all over the body (Figure 37.20c). After mating, the females lay millions of eggs which develop into microfilaria, completing the lifecycle.

37.4.3 Clinical manifestations of lymphatic filariasis

The clinical manifestations of the disease are as a result of the inflammation and damage to the lymphatic vessels caused by the person’s own immune response trying to reject the worms, and when vessels become blocked by clusters of worms. The overall effect is to disrupt the lymphatic system, which normally collects tissue fluids draining from the body’s cells and returns the fluid to the blood stream. If the lymphatic drainage is blocked, the lower limbs and sometimes also the genitals become hugely swollen with fluid – a condition called lymphoedema (pronounced ‘limf-ee-deem-ah’). Most infections do not produce symptoms, but in people where the lymphatic drainage is badly damaged the common symptoms include hydrocele (swelling of the scrotum, pronounced ‘hy-droh-seel’), swelling of the legs and feet, and thickening of the skin into folds (Figure 37.21). Infection of the swollen skin folds by bacteria is a frequent cause of very painful attacks. Patients suffer from episodes of fever and around 40% develop kidney damage.

37.4.4 Diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis

![]() Suspected cases of lymphatic filariasis should be referred to the health centre.

Suspected cases of lymphatic filariasis should be referred to the health centre.

You can suspect lymphatic filariasis from the clinical manifestations, but the diagnosis can only be confirmed by laboratory tests to reveal the microfilaria in blood smears viewed with a microscope. Adult worms blocking the lymphatic vessels or nodes are difficult to reach. Therefore, if you live in an endemic area and you suspect a case of lymphatic filariasis, you should refer the patient to the nearest health centre for further testing and treatment.

37.4.5 Prevention and control of lymphatic filariasis

Lymphatic filariasis is one of the few communicable diseases that the WHO believes could be eradicated (totally removed from all populations in the world, never to return) with the currently available prevention and control measures. These are:

- Integrated vector control (IVC) measures to reduce the mosquito population, including indoor residual spraying, use of insecticide treated bed nets (ITNs), and environmental management such as drainage and filling of breeding sites for the mosquitoes.

- Community-directed mass drug administration (MDA). The WHO recommends a two-drug regimen of albendazole and diethylcarbamazine (or ivermectin in areas where onchocerciasis is also endemic), which is administered to the entire at-risk population once every year for four to six years. These drugs are prescribed by staff at health centres.

- Personal protective clothing to reduce exposure of skin to mosquito bites, and use of ITNs.

- Rapid case detection and referral to prevent cases from spreading.

- Education in the community about the causes and modes of transmission of lymphatic filariasis, and ways to protect themselves from mosquito bites. Encouraging acceptance of the mass drug administration programme is an important health education message that you can deliver if your community is affected. You also have a key role in educating patients about how to prevent and alleviate disabilities and pain due to lymphatic filariasis, as described in the final part of this study session.

37.4.6 Prevention and alleviation of disability due to lymphatic filariasis

The methods described here are also used to reduce the swelling due to podoconiosis (non-infectious elephantiasis, Study Session 39).

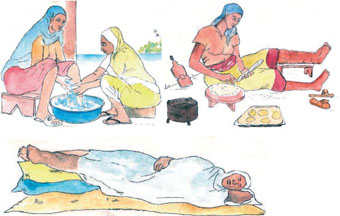

Patients with lymphoedema and thickened skin folds (for example, as in Figure 37.21) can be empowered to manage their symptoms and reduce their discomfort and pain through simple, but rigorous, hygiene techniques. You should educate them to wash the affected parts carefully every day, especially between the folds of thickened skin, and gently dry the area with a clean cloth. They should elevate (raise) swollen legs as much as possible whatever they are doing during the day and raise the foot of the bed or sleeping mat at night (Figure 37.22). Advise the patient to exercise the limbs any time and anywhere, as often as possible, to help the fluid to exit from their swollen limbs.

In the next study session, you will learn about two more diseases of public health importance in Ethiopia – rabies and taeniasis (tapeworm disease) – which are spread to humans by warm-blooded animals (dogs and cattle).

Summary of Study Session 37

In Study Session 37, you have learned that:

- Schistosomiasis is caused by parasitic flatworms transmitted from freshwater snails to humans. It is common in communities living near rivers, lakes and streams, where infected people shed Schistosoma eggs when they urinate or defaecate into the water.

- Schistosoma mansoni affects blood vessels in the intestines and causes abdominal pain, bloody diarrhoea and anaemia. Schistosoma haematobium affects blood vessels in the bladder and causes pain during urination and bloody urine.

- Leishmaniasis is caused by protozoan parasites transmitted to humans through the bite of sandflies, which breed in warm, humid places such as rubbish collections and rodent burrows.

- Leishmania donovani causes the life-threatening condition called visceral leishmaniasis (or kalaazar), manifested by fever, weight loss and swelling of the liver and spleen. Three other Leishmania species cause cutaneous leishmaniasis, which manifests as ulcers in exposed areas of skin.

- Onchocerciasis is caused by a nematode worm (Onchocerca volvulus) transmitted in the bite of blackflies, which breed near fast-flowing rivers with good vegetation. The microscopic microfilaria cause skin nodules and can migrate to the eye, causing blindness.

- Lymphatic filariasis (or elephantiasis) is caused by a nematode worm (Wuchereria bancrofti) transmitted to humans in the bite of female mosquitoes. The worms block the lymphatic system, causing swelling of the limbs and sometimes the genitals, resulting in severe pain, disability and bacterial infection of thickened skin folds.

- Integrated vector control measures such as indoor residual spraying, use of insecticide treated bed nets (ITNs), chemical treatment of water, use of personal protective clothing and environmental management to destroy vector breeding sites are key interventions to prevent these vector-borne diseases.

- Mass drug administration of the entire at-risk population at regular intervals for several years is the recommended strategy to prevent onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis in endemic communities.

- Educating the community on the modes of transmission of vector-borne diseases, effective prevention strategies, and early diagnosis and referral of patients are important activities for Health Extension Practitioners and Workers in affected areas.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 37

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering the following questions. Write your answers in your Study Diary and discuss them with your Tutor at the next Study Support Meeting. You can check your answers with the Notes on the Self-Assessment Questions at the end of this Module.

SAQ 37.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 37.1, 37.2 and 37.5)

How many communicable diseases can you name that can be prevented by integrated vector control methods? (Think about all the vector-borne diseases you have learned about in this Module – not just in this study session!)

Answer

Malaria, relapsing fever, typhus, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis are all vector-borne diseases prevented by integrated vector control methods. Did you remember all seven of these conditions?

SAQ 37.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 37.1 and 37.2)

Complete Table 37.1 by writing the common name of the vector in the second column beside the disease that it transmits.

| Vector-borne disease | Vector |

|---|---|

| Schistosomiasis | |

| Leishmaniasis | |

| Onchocerciasis | |

| Lymphatic filariasis |

Answer

The completed table appears below.

| Vector-borne disease | Vector |

|---|---|

| Schistosomiasis | Freshwater snails |

| Leishmaniasis | Sandflies |

| Onchocerciasis | Blackflies |

| Lymphatic filariasis | Mosquitoes (Culex and Anopheline females) |

SAQ 37.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 37.1, 37.2, 37.3, 37.4 and 37.5)

Imagine that you have been assigned to Humera and you see a 25-year-old man who has signs of severe weight loss, fever and a hugely enlarged abdomen.

- a.What is your diagnosis?

- b.What should you do for this patient?

- c.What should you educate his family about the mode of transmission and how to protect themselves from this disease?

Answer

- a.The signs of this disease strongly suggest that the patient is suffering from visceral leishmaniasis.

- b.Inform the family that the disease is severe and life-threatening; immediately refer the patient to a higher health facility to confirm the diagnosis and begin treatment.

- c.Educate the family about the mode of transmission of the disease by sandflies biting humans to take a blood meal. Advise them to destroy all rubbish heaps and rodent burrows around the house, and fill cracks in walls where sandflies like to breed. They should agree to their house being sprayed with insecticide and they should cover exposed skin and sleep under insecticide-treated bed nets to avoid sandfly bites.

SAQ 37.4 (tests Learning Outcomes 37.1, 37.3 and 37.4)

- a.How could you tell the difference between the skin lesions of onchocerciasis and cutaneous leishmaniasis?

- b.In addition to the physical consequences of the skin lesions, what impact can both these diseases have on the lives of affected people?

Answer

- a.Cutaneous leishmaniasis is manifested by open skin ulcers, which may be large (see Figure 37.9). The skin lesions of onchocerciasis are characterized by changes in skin colour and the formation of large numbers of nodules (look back at Figure 37.15a).

- b.In addition to the physical disabilities and pain caused by these conditions, the disfiguring appearance of onchocerciasis nodules and cutaneous leishmaniasis ulcers often results in stigmatization, discrimination and rejection of patients by their communities.

SAQ 37.5 (tests Learning Outcomes 37.1, 37.3 and 37.5)

- a.Which regions of Ethiopia are most affected by schistosomiasis?

- b.Why are children in affected communities particularly at risk of schistosomiasis, and what impact does the disease have on their lives, in addition to the pain and discomfort it causes?

Answer

- a.Highland lakes and rivers in several parts of Ethiopia (e.g. Ziway, Hawassa, Bishoftu, Wonji, Haromay, Jimma, Bahir Dar, etc.) are affected by Schistosoma mansoni, which affects the intestines. Schistosoma haematobium, which mainly affects the bladder is limited to lowland swampy land and floodplains in the Awash and Wabe Shebele valleys and along the border with the Sudan.

- b.Children are most at risk because they are more likely to go swimming in infected water, or stand in the water while fishing. They are also more likely than adults to stand in the water to urinate or defaecate. In addition to the pain caused by the disease, infected children are usually stunted in their growth and perform poorly at school.