Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:24 PM

Parkinson's: managing palliative and end of life care

1 Introduction

The purpose of this course is to enhance your understanding of palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s and to guide you through this journey alongside your client and their carers.

Palliative care is the active total care of people whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment, and involves the physical, psychological, spiritual and social aspects of their care.

End of life care involves the delivery of care during the period of time when the person’s condition is actively deteriorating, to the point where death is expected.

This course aims to improve the outcomes of this journey for all involved by encouraging early conversations about advance care planning, and the need to make decisions about treatments the client may or may not wish at the end of their life. The course highlights involvement of the multidisciplinary team and each member’s important role in supporting and managing the physical, social, psychological and spiritual needs the client and their carers may experience throughout this journey.

Health and social care professionals from various disciplines will be taking this course. We will therefore use the word ‘client’ to refer to a person with Parkinson’s who you work with. You may usually use ‘patient’, ‘resident’ or another term.

Before you commence this course, think about how you will study. Not just whether you will study online or download for reading offline or on a mobile device, but how you will use the course in practice. As you progress through the course, there will be some reflective exercises. These are important to help you think about your past practice and consider if you might be able to improve this in the future.

There are quizzes at the end of each section, allowing you to assess what you have learnt. At the end of the course there is a final quiz which is a review of all the sections. You will be able to earn a digital badge if you gain a pass rate of at least 65% in the final course quiz.

Our approach

People with Parkinson’s have been involved in the decisions about the management of their condition throughout its progression. Therefore, it is important that this continues as they approach the end of life. It is essential that health and social care professionals educate clients throughout the condition’s trajectory about its progression and the possible impact in the advanced stage. This will give the client the knowledge and autonomy to make informed choices and decisions in advance about their management at the end of life, and to indicate how they would like their relatives/carers to be involved.

The following video provides you with a brief overview of this course about palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s, and the content of the course.

Transcript

Welcome to the ‘End of life care in Parkinson’s’ online course. This course has been designed for health and social care professionals, who already have experience working with people with Parkinson’s, but wish to enhance their knowledge of end of life care in Parkinson’s. If your knowledge and experience of Parkinson’s is limited, we suggest you first take the course ‘Understanding Parkinson’s for health and social care staff’.

The course is designed around a series of sections, which will look at different aspects of end of life care in Parkinson’s. In the first section, we will examine the UK directives that have influenced the development of palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s, which is quite a recent development, in the management of Parkinson’s.

The second section examines some of the challenges facing health and social care professionals when predicting and managing the end of life care of a person with Parkinson’s, due to the slowly progressive and fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s. We will discuss the importance of the introduction of principles of palliative care early in the Parkinson’s journey. This will highlight the importance of education for professionals, to enable them to have open and honest conversations about the advanced phase, and issues around advanced care planning and end of life care. We will examine the challenges of advanced care planning, the need for discussion, and documentation, of the client’s wishes, and their decisions around advance decision to refuse treatment, or deciding if they wish to name a person as their power of attorney.

The third section examines the management of people with Parkinson’s at the end of life phase. We will identify the indicators for end of life approaching, and then examine in detail the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual management of this phase. We will consider the carers, and the impact on their own health and wellbeing, recognising their needs as their care role changes as the illness progresses, especially at the end of life phase, and their continued need for support through bereavement.

By the end of the course, you will have gained a greater understanding of palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s. You should feel confident in having open and honest conversations with your clients about their progressive, life-limiting illness, and enabling them to make decisions about their end of life care early in their disease trajectory. This course will give you the necessary knowledge to recognise the symptoms indicating end of life in Parkinson’s, and where appropriate, to support and direct the multidisciplinary team and effectively managing the client’s physical, psychological, spiritual and social care needs. We will enhance your knowledge of the importance of the carer’s role, and their needs during this advanced stage of Parkinson’s, enabling them to have the appropriate coping strategies, to manage this journey right through to bereavement.

Learning outcomes of the course

- Demonstrate an understanding of the principles of palliative and end of life care and how these can be applied in Parkinson’s.

- Identify the challenges in practice of applying palliative and end of life care principles in Parkinson’s.

- Confidently discuss the theory of advance care planning and the issues involved, such as power of attorney or advance decision to refuse treatment.

- Identify symptoms which indicate the end of life phase in Parkinson’s and highlight the issues in management of this phase.

- Be aware of the family and/or carers of the client and their needs throughout the end of life phase through to bereavement.

1.1 Why are we here?

Before we start, let’s think about reasons for studying this course about Parkinson’s palliative and end of life care. You might have decided to take this course for one or more of these reasons:

- You are working as part of the specialist team to support a number of people with Parkinson’s.

- You feel you could do a better job if you understood palliative and end of life care.

- Your expertise is in palliative and end of life care, but you have limited experience of Parkinson’s.

- Your manager told you to take this course.

- You want to increase your knowledge around Parkinson’s to learn more about specific topics.

As much as possible we have designed the course to support those different contexts. Please remember it is your responsibility to determine whether specific recommendations are relevant to your role, as many are aimed at the specialist team.

We have created a reflection log for you to record your thoughts when answering questions throughout the course. Remember there are no wrong answers here.

Reflective exercise

Use your reflection log to answer the following questions:

- Why did I decide to take part in this course and what would I like to gain from it?

- What experience do I have in palliative and end of life care? (A short paragraph will suffice.)

- What experience do I have in the management and support of a person with Parkinson’s at the end of life stage?

- How did I find this experience? For example, did I find it challenging, or did my present experience allow me to manage my client with confidence and satisfaction?

You can use your log at the end of the course to reflect on the knowledge you have gained and how you can use this in the future to enhance your practice.

2 Palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s

The purpose of this section is to give you an understanding of the principles of palliative and end of life care and how these apply in Parkinson’s.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section you should be able to describe the following:

- The recognised definition of palliative and end of life care.

- The principles of palliative and end of life care.

- Why it is important to apply palliative and end of life care early in the trajectory of Parkinson’s.

- The UK directives which have influenced the development of palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s.

As you work through this course, consider your role and how to apply this knowledge to enhance your practice in palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s.

2.1 What is the definition of palliative care?

The word palliative derives from the Latin ‘pallium’, meaning cloak or covering. It is reflected in the Middle Eastern blessing: “May you be wrapped in tenderness, you my brother, as if in a cloak.”

We could use the word ‘cloak’ to symbolise the holistic care we aim for, which encompasses the physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects of care, and is highlighted in the following definition of palliative care:

“Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.” (World Health Organization, 2020)

The early development of the palliative care ethos was synonymous with cancer care, but as research in palliative care developed it became recognised that people living with life limiting, non-malignant illness had as many complex care needs as those suffering with cancer. The recognised definition of palliative care devised by the World Health Organization (WHO) was therefore revised to incorporate the care of those with life limiting illnesses.

Further reading

The following are palliative care guidelines specific to UK geographical areas:

Actions for End of Life Care 2014-2016 NHS England

End of Life Care resource page NHS England

Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care a national framework for local action 2021-2026

Strategic Framework for Action on Palliative and End of Life Care (2015) Scottish Government

Scottish Palliative Care Guidelines NHS Scotland

Palliative care (Wales) NHS Wales

Living Matters, Dying Matters strategy 2010 Department of Health Northern Ireland

National Guidelines for Health and Social Care Professionals The Palliative Hub (Professional) (Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland)

Review of the Implementation of the Palliative and End of Life Care Strategy (March 2010) January 2016 The Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority

UK Government commitment to high quality end of life care UK Government, Department for Health

2.2 What are the principles of palliative care?

The WHO developed the following broad principles of palliative care that are applicable across a spectrum of care settings and diagnoses:

Palliative care:

provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

intends neither to hasten nor postpone death

integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care

offers a support system to help patients to live as actively as possible until death

offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement

uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families

will enhance quality of life and may also positively influence the course of illness

is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

(World Health Organization, 2002)

Reflective exercise

In the following videos a hospice specialist nurse and a Parkinson’s specialist nurse identify and discuss the differences in the management of a client with cancer and a client with Parkinson’s at the end of life phase of their illness. Their discussion is based on the principles of palliative care.

As you watch each video make notes on the discussion points. Try to identify which principles are being discussed. Use your notes to write a short reflection in your reflection log on your experience of managing a client at the end of life phase, briefly discussing how you applied the principles of palliative care.

Transcript

Dorothy Hardywood, Parkinson’s Specialist Nurse

This is quite a new concept in Parkinson’s that we actually look at palliative care within Parkinson’s. The principles of palliative care have long been established for cancer care, but we are now looking at how we apply these within Parkinson’s. Firstly, we have been talking about applying palliative care early in the disease trajectory, and in Parkinson’s management, we would actually know the client from early in their diagnosis, so we would support them through diagnosis, and the commencement of medication. Our input would then increase again, as their condition progresses, when they would be on a more complex regime of medication, or complex treatments, like Apomorphine, pump or Duodopa® pump, or maybe have undergone deep brain stimulation. In the advance stage of Parkinson’s, we would have much more input because of the complex symptoms, their physical deterioration, and many hospital admissions, and also the stress that is on the carers, so as a Parkinson’s nurse especially, we are there to support the carer through this very stressful time.

Debbie Knight, Hospice Specialist Nurse

For patients who have received a cancer diagnosis, they can actually be referred for specialist palliative care at different trigger points throughout their disease trajectory: initially, at diagnosis, especially if they have been told that the treatment intent is palliative rather than curative. Secondly, where they have perhaps been having some palliative interventions, chemotherapy or radiotherapy, which hasn’t actually been effective and their disease has progressed. Thirdly, if they have had a recurrence of their cancer, or maybe further metastatic disease has occurred, and finally then, at the end of life, they would be referred to our service. At initial referral, an early intervention would involve for us very much focusing on complex symptom management, but also providing care and support to the family as well as the patient. Obviously, there is a difficult journey ahead for both of them, and while we can provide a lot of the support that they need, very often they need referral on to other services, especially where maybe more intense psychological, or emotional, or social, and spiritual support is required, so we would very often signpost them to the other services, other healthcare professionals, and maybe even other voluntary organisations who would be involved at that stage. And we just support them, I suppose, through their whole journey, right up until the end of life.

Transcript

Dorothy Hardywood, Parkinson’s Specialist Nurse

In the management of Parkinson’s, we would usually adopt the holistic approach in that we are looking after their psychological, their physical, their social, and spiritual care. This would enhance the quality of life for that person with Parkinson’s, and also to those closest to them. When appropriate, we would think about advance care planning, because we feel that it gives the client the knowledge and the autonomy to make decisions about their future care, and to be in control of their care, which is very important to their management of, or acceptance, of their condition. We would also involve the multidisciplinary team, because they would be involved in the very complex and distressing symptoms which may occur at the end of life.

Debbie Knight, Hospice Specialist Nurse

Obviously, the whole aim of palliative care is to promote the best quality of care for patients for as long as possible, so while we can bring a lot to that, we also would rely very heavily on our multidisciplinary team as well, because we are meeting those holistic needs – not just the physical, but the psychological, social and emotional and spiritual needs of the patient. So from diagnosis, there is very much a multidisciplinary approach to care. We would very often be involved in advanced care planning discussions. In fact, those can take place sometimes at our very first consultation with patients, but we would be very much led by the patient themselves whether they want to actually go down that road and have those conversations. But there are other situations where we would feel that there is a more appropriate person to have those conversations and that may be their oncologist, their own GP, or some other healthcare professional who actually knows the patient better, and has a greater rapport with the patient, so we are very much led by the patient and the multidisciplinary team in that respect.

Transcript

Dorothy Hardywood, Parkinson’s Specialist Nurse

The multidisciplinary team are usually involved from diagnosis of Parkinson’s but as the disease progresses, their input will change, and normally towards the end of life phase, their role will become more palliative and supportive. In the management of the clients through their trajectory, we would involve the family. They are very much involved in the discussions about the treatments, discussions about the progressions of the disease. It is very important to include the carers and to acknowledge their needs. We support them as best we can, so sometimes if we feel that our knowledge is inadequate, we refer them to other agencies which maybe could support them better through that journey. We are thinking about people like charitable organisations, other health professionals, or support groups.

Debbie Knight, Hospice Specialist Nurse

I suppose where I would see my role developing at this stage, I would use some of my advanced communication skills, and some of the principles of breaking bad news, to engage in those very difficult conversations with patients and their families. These sorts of conversations can include preferred place of care, preferred place of death, maybe discussions around resuscitation, whether they would want to be readmitted to hospital again or not, and just kind of planning for the end of life, what their wishes are, and having those conversations with their family. So, while we can begin some of those discussions and engage with those, we may also then, you know, again, involve other healthcare professionals. For example, we may initiate a discussion about resuscitation, but we would also want that followed up with their own GP, to kind of, you know, have that conversation as well, and make sure that is documented and communicated with the right healthcare professionals.

The NICE guideline (CG35) for Parkinson’s (2006) indicated that principles of palliative care should be applied from diagnosis to end of life care. This improves quality of life for people with Parkinson’s and helps the family’s transition through increasing levels of disability while maintaining autonomy and dignity. The revised NICE guideline (NG71) does not state this, but does not offer an alternative. You could assume from this that applying from diagnosis is now accepted good practice. For further details see section 1.9 Palliative care of the revised NICE guideline (NG71) - Parkinson’s disease in adults (2017).

The trajectory of Parkinson’s is variable and complex, making it essential that each person is assessed regularly by the multidisciplinary team and their changing needs are managed on an individual basis.

For this multidisciplinary care management to succeed, it is important that there is excellent communication and co-ordination between all professionals involved and that they are trained and competent in palliative care. Enabling the delivery of a high standard of care will maximise the quality of life for people with Parkinson’s and their families. It is important that these professionals recognise when the expertise of other specialist palliative care services is required and an appropriate referral needs to be initiated.

2.2.1 Dynamic model of palliative care services

Palliative care services should adopt a dynamic model where the palliative care services will interject at different periods during the condition’s trajectory according to the needs of people with Parkinson’s.

The animation below depicts the changes in belief about when palliative care should be introduced in a progressive condition’s trajectory. It moves from the traditional medical model, where palliative care was only available at the end of life, right through to the present day model, where we now recognise palliative care as a dynamic process. The palliative care input is guided by trigger or crisis points throughout the condition’s trajectory, which may only require palliative input for a brief period. This brief input is to resolve the crisis – such as particularly distressing symptoms, deterioration in the condition or at the start of new interventions, ie gastrostomy feeding – then services are withdrawn until next required.

Transcript

Model A The Traditional model of late involovement of palliative services

In the past because palliative care was related only to cancer care, there would have been a defined trajectory shifting from curative treatments to palliative/end of life care.

Model B The model of early and increasing involvement of palliative services

This traditional model was not sustainable as management of cancer with palliative chemotherapy even in the late stages of the illness, aiming to improve quality of life rather than extending life. So a pathway of integrated care was developed that as curative treatments reduced, the palliative care management increased.

Model C The model of dynamic involvement of palliative services based on trigger points.

Research highlighted the need for palliative care input in neurological conditions. But these conditions have varying prognosis with varying needs, and so a new dynamic model of care was required, in which palliative services would be episodic involvement at certain trigger points, with less or no contact between these episodes.

These trigger points may have been identified by the Health and Social care team as unmet palliative care needs, and input from specialist palliative care requested.

Such “trigger” points may be at diagnosis, marked deterioration in the condition physically or psychologically, management of complex symptoms, ie pain, or at the commencement of new interventions such as gastrostomy, and at the EoL.

The National End of Life Care Programme’s framework for implementing end of life care in long term neurological conditions (2010) recommends the involvement of palliative care at an early stage in Parkinson’s to improve symptom management and therefore quality of life. Yet research continues to highlight barriers such as lack of awareness and understanding of palliative care services and the failure of some health and social care professionals to discuss the life limiting aspects of Parkinson’s. They therefore find it difficult to determine the appropriate time to initiate conversations about advance care planning (ACP).

If the palliative care approach is adopted by the health and social care professionals from diagnosis, ACP can be integrated into initial care planning and evaluated regularly over the course of the condition.

This will be discussed in greater detail in section 3

2.3 What is the definition of end of life?

Patients are ‘approaching the end of life’ when they are likely to die within the next 12 months. This includes patients whose death is imminent (expected within a few hours or days) and those with:

a) advanced, progressive, incurable conditions

b) general frailty and co-existing conditions that mean they are expected to die within 12 months

c) existing conditions if they are at risk of dying from a sudden acute crisis in their condition

d) life threatening acute conditions caused by sudden catastrophic events.

(Leadership Alliance for the Care of Dying People, 2014)

It is difficult to find a definition that fits all possible life limiting conditions, and in the case of Parkinson’s, in which the progression is slower, fluctuates and is at times unpredictable.

It is argued that using the ‘surprise question’ – Would I be surprised if the person in front of me were to die within the next six months to a year? – would not be appropriate and is not taking into account the ‘palliative phase’ of approximately two years prior to death for people with Parkinson's.

In the following film, Dr Vas Krishnaswami discusses the challenges of using the ‘surprise question’ in Parkinson’s.

Transcript

Dr Vas Krishnaswami

The surprise question would often refer to a statement where we see someone that we make the prediction: “Would I be surprised to see the person fade away in 6 to 12 months’ time”, so, this statement is often difficult with Parkinson’s disease, as the disease, illness, and cause, can be fluctuant. Any integrant (internal?) illness like a chest infection can bring down the person in terms of physical abilities, and this can falsely give the impression that they are in a terminal phase, but with treatment and appropriate rehabilitation, the patient can often return back nearly to the quality of life that they had before. So this decision, or other statements of a surprise question, is extremely difficult in Parkinson’s disease, primarily because of the fluctuant nature of Parkinson’s disease.

To overcome these difficulties some professionals argue that there is a need to avoid traditional prognosis-based approaches for end of life care referrals, and instead to focus on the person, their experiences of their life limiting condition and their present needs. We will find that the principles of end of life care incorporate this point of view.

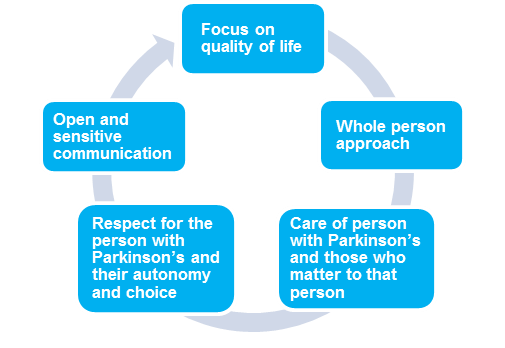

2.4 What are the principles of end of life care?

These principles are useful to guide health and social care professionals in the delivery of best practice, high quality end of life care for people with Parkinson’s.

Principles of end of life care

A focus on quality of life involves good symptom control, relief from pain and other distressing symptoms.

A whole person approach takes into account the person’s past life experience and current situation.

The care of people with Parkinson’s and those who matter to that person promotes an awareness of the needs of the family and/or carer due to major changes in their life.

Respect for the person with Parkinson’s and their autonomy and choice recognises that timely information promotes educated choices about treatment options, and allows discussion about advanced care documents and preferred place of care.

Open and sensitive communication will prompt discussion on advance care planning issues, personal feelings and family relationships. It is important that family and/or carers have their opportunity to express their feelings too.

Reflective exercise

Reflect on these principles of palliative and end of life care within your care setting. In your reflection log, record the key words that you believe summarise how you would approach palliative and end of life care.

Discussion

In your reflection you may have considered the following:

Holistic approach – both to the client and the ethos of care. Holistic will incorporate the physical, spiritual, psychological and social care needs of the client.

Multidisciplinary team approach – the skill mix of the team will be used to manage the client’s and their family's needs.

Person-centred care – the client’s wishes and needs are at the centre of the care planning.

Autonomy – the team will recognise the client’s right to decide and will provide them with the information to enable an informed choice.

Quality of life – the aim of holistic care is to provide improved quality of life through control of symptoms and rehabilitation.

Respectful and trusting relationships – with the client and those important to them.

Interprofessional communication – is important to promote co-ordinated and dynamic delivery of care.

Support network – using statutory, voluntary and community groups/services to provide comprehensive support for the client and family and/or carers.

2.5 Why is it important to apply these principles early in the trajectory of Parkinson’s?

As we have worked our way through section 2 we have made several references to the need for palliative care principles to be introduced early in the trajectory of Parkinson’s. The key reasons for early introduction are summarised below:

- Research has highlighted the benefits of early introduction of palliative care principles in management of Parkinson’s (Tuck et al, 2015).

- It encourages professionals to have open and honest conversations about the advanced phase of Parkinson’s and to have early discussions about the client’s preferences and wishes for their care and management in the advanced and end of life stages.

- It supports the benefits of advance care planning and allows the client to discuss issues around lasting power of attorney, Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) and decisions around resuscitation. (There are different names for this in each of the UK nations, more information can be found on the Parkinson’s UK website.)

- Empowering the health professional to have these conversations earlier with clients promotes person-centred care and a holistic approach to end of life care.

- There is a high incidence of cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s as the condition progresses. Therefore the early introduction of the principles of palliative care, which allows them to discuss wishes, fears and concerns for their future, will provide the client with a sense of control and ownership of their future care.

2.6 Which UK directives have influenced palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s?

Across the UK various directives influence palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s. These include:

Department of Health (2005) National Service Framework for Long-Term Conditions

Quality requirement 9 in this framework addresses end of life care and states that:

“People in the later stages of long-term neurological conditions are to receive a comprehensive range of palliative care services when they need them, to control symptoms, offer pain relief, and meet their needs for personal, social, psychological and spiritual support, in line with the principles of palliative care.”

NICE (2017) Parkinson's disease in adults

The original guidelines from NICE were revised in 2017 and include recommendations on palliative care:

1.9 Palliative care

Information and support

1.9.1 Offer people with Parkinson's disease and their family members and carers (as appropriate) opportunities to discuss the prognosis of their condition. These discussions should promote people's priorities, shared decision-making and patient-centred care. [2017]

1.9.2 Offer people with Parkinson's disease and their family members and carers (as appropriate) oral and written information about the following, and record that the discussion has taken place:

- Progression of Parkinson's disease.

- Possible future adverse effects of Parkinson's disease medicines in advanced Parkinson's disease.

- Advance care planning, including Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) and Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNA CPR) orders, and Lasting Power of Attorney for finance and/or health and social care.

- Options for future management.

- What could happen at the end of life.

- Available support services, for example, personal care, equipment and practical support, financial support and advice, care at home and respite care. [2017]

1.9.3 When discussing palliative care, recognise that family members and carers may have different information needs from the person with Parkinson's disease. [2017]

National End of Life Care Programme et al (2010) End of life care in long term neurological conditions: A framework for implementation

This states that the changes in a neurological condition’s progression are recognised in all care settings as triggers for the introduction and subsequent involvement of palliative care. The provision of this care should be based on holistic assessment. This includes multidisciplinary and multiagency collaboration, good interprofessional communication, and regular review of the needs of the client and of those most important to them.

2.7 Summary of section 2

We have looked in detail at the palliative and end of life definitions and principles of care. By applying these principles early in the condition’s trajectory, it improves the outcomes of care. We also examined the challenges of applying these principles in practice, and finally examined the directives which have influenced the development of palliative and end of life care in Parkinson’s. You will have considered how this information can help you to improve your practice and share your knowledge with other health and social care professionals. We will now look at a case study exercise. You can record your thoughts in the reflection log.

Reflective exercise

In this exercise we introduce Mr Edwards, who has been newly diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Think back to the information in section 2 about the definition and principles of palliative care and consider how you would apply these as you read through the case study.

Case study

Mr Alex Edwards is a 55-year-old architect, married with two teenage children. He went to see his GP complaining of a painful right shoulder, which he feels is also affecting his handwriting as it has become small and illegible. This worries him because it is impacting his job. He also states that his sleep pattern is disturbed because he feels stiff and sore at night and unable to turn over in bed. His GP explains that he might have Parkinson’s, explains what it is and then makes a referral to a neurologist.

Because Mr Edwards and his family are anxious about his diagnosis, he books a private appointment with a neurologist to reduce the waiting time. The neurologist confirms he has Parkinson’s and after discussion with Mr Edwards decides to commence him on a dopamine agonist, and arranges to review him in three months.

In the meantime, Mr Edwards was referred to the Parkinson’s specialist nurse, who organised to meet him and his family. They were able to discuss their thoughts and feelings about the diagnosis and ask questions about Parkinson’s and the medication. The Parkinson’s nurse gave them further written information on Parkinson’s, as well as her work contact number in case they required further advice in the near future.

She referred Mr Edwards to physiotherapy to assess and offer him advice about exercise and how to maintain his physical wellbeing. She also referred him to occupational therapy to discuss his work and management of his handwriting, to enable him to maintain his confidence at work.

She provided information about Parkinson’s UK, explaining how everything the charity does is shaped by people affected by Parkinson’s. She also signposted the family to a Parkinson’s UK local support group.

Reflective exercise 1

Reflect on the case study and identify how the psychological, physical and social aspects of care are being supported here.

Use the reflection log to record your thoughts.

Discussion

In your reflection you may have considered the following:

By supporting Mr Edwards and his family with information, education and guidance on his condition and the medication choices, the GP, neurologist and Parkinson’s specialist nurse are aiding Mr Edwards to accept his diagnosis and to make informed choices about his treatment.

His quality of life is enhanced through informed choices about medication, as well as appropriate referrals to the occupational therapist and physio to maintain his physical ability and assist him to manage at work, relieving his stress about his ability to continue at work.

His family and Mr Edwards will receive information and support from Parkinson’s UK and the local support group, which will be invaluable as his condition progresses.

The Parkinson’s specialist nurse will be their main point of contact offering a support system to help Mr Edwards and his family come to terms with the diagnosis and ongoing management.

Reflective exercise 2

In your reflection log identify how some of the principles of palliative care are being applied in this early stage of diagnosis.

Discussion

In your reflection you may have considered the following:

From the principles of palliative care we have incorporated a team approach, offering a support system to enhance quality of life through involvement of the allied health professionals.

Offering family support through the support group and Parkinson’s UK.

Through education, information and planned professional support, his psychological, physical and social wellbeing are enhanced

Quiz questions

Now try Quiz 1.

This is the first of three section quizzes. You will need to try all the questions and complete the quiz if you wish to gain a digital badge. Working through the quiz is a valuable way of reinforcing what you’ve learned in this section. As you try the questions you will probably want to look back and review parts of the text and the activities that you’ve undertaken and recorded in your reflection log.

3 Advance care planning

Section 2 highlighted the difficulty of predicting end of life in Parkinson’s. This section develops this, exploring the challenges of predicting end of life in Parkinson’s and how to manage these challenges. In particular it examines advance care planning and the issues around lasting power of attorney and Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT).

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section you should:

- be able to identify the challenges in predicting and managing the end of life phase in Parkinson’s

- gain an in-depth understanding of advance care planning (ACP) and the importance of its introduction at the appropriate time in the progression of the condition

- gain an understanding of the importance of recognising the needs of people with Parkinson’s and those closest to them in directing ACP

- have an understanding of lasting power of attorney and Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment.

3.1 Challenges of predicting end of life care in Parkinson’s

In the following video, the consultant discusses the challenges of predicting end of life in Parkinson’s. In the further videos he discusses how the fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s, polypharmacy and complex invasive treatments affect the accuracy of predicting end of life in Parkinson’s.

Transcript

The end of life definition is often difficult to predict in patients with Parkinson’s. This is primarily because of the long trajectory of the illness. There are two aspects which we would normally look into in making the end of life decision. One aspect is mental frailty, where the ability to think and reason, that is involved in day-to day-activities, and physical frailty, which would mean the level of dependence on others that becomes progressively to the state that they can actually be in a nursing home level of care, would be synonymous with the end of life care. But because the illness can be so prolonged, it becomes extremely difficult to predict.

Key challenges in predicting the end of life in Parkinson’s

- Long duration of the condition.

- Unpredictable and fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s. This may include infections, reactions to drug changes and gradual deterioration.

Transcript

The advanced therapies that we normally associate with Parkinson’s are Apomorphine pump, which is a medication that is given through a needle under the skin, or Duodopa® pump which is a medication that is given through a small tube that is inserted into the small bowel, or through a deep brain stimulator which is an electrode system planted in the brain, to help manage Parkinson’s. With advanced therapies, the therapy and treatment itself can have an impact on Parkinson’s quality of life. If I have to give you an example, with Apomorphine pump, patients can experience visual hallucinations and increased sleepiness during daytime. This can be particularly difficult to manage, but the treatment strategies that could involve potentially getting the medication dose at a reduced state can actually improve quality of life in these patients, and also reduce the care burden for these patients. The physical symptoms might suffer as a consequence of breaking down the treatment, but it can actually improve the overall quality of the patient. And we must remember, these advanced therapies like Duodopa® or deep brain stimulators are there to help support Parkinson’s management, and they do not in any way alter the course and progress of Parkinson’s itself. Hence, these advanced therapies can sometimes be difficult to predict end of life care in these individuals.

- Neuropsychiatric problems – the high prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s.

Transcript

As the disease progresses, the brain function progressively decreases. Around 60% of Parkinson’s patients, in approximately 12 years’ time, will develop dementia. The commonest form of neuropsychiatric problems that we would see, is hallucinations, like seeing children, or little animals, around the house, is what typically a Parkinson’s patient would describe. Dementia would mean that the mental capacity for day-to-day function activities would decline and, hand in hand, the physical frailty also occurs. This would be, typically: the foremost, impact swallowing abilities; frequent falls; and frequent hospital admissions; and increased level of care requirements like placement in nursing home. But even with the support of therapy, the patients can actually manage to live a few years, and it actually becomes difficult even with dementia to predict the end of life in Parkinson’s patients.

- Complex multidisciplinary care – due to increasing physical disability and loss of independence, medications are less effective or disabling side effects develop.

- There can be unpredicted multiple crises, ie infection, falls and/or hospital admissions.

- Most people with Parkinson’s will die with their condition and not from it.

Transcript

Parkinson’s, when it is present, the patients can often have other co-existing conditions. In the natural course of progress for these patients, it depends on the age in which the Parkinson’s is diagnosed, presence of other co-existing medical conditions, such as stroke, or progressive heart condition, or progressive chest conditions. These all impact on the natural course of Parkinson’s disease, and it becomes extremely difficult to predict the end of life in these individuals, as Parkinson’s may not be the one that actually brings them down - the co-morbid condition is the one that can actually bring them down. Say, for example, chest conditions like pneumonia, or recurrent aspiration-related chest conditions could actually bring them down. This makes it difficult to predict end of life in these individuals, but our care should be focused on providing a holistic approach for each of the individuals, not purely based on the diagnosis of Parkinson’s.

3.2 How do we manage the challenges of predicting end of life care in Parkinson’s?

As practitioners you may approach and deal with these challenges in a number of ways:

An individual holistic assessment that identifies changing needs by taking into account the physical, social, psychological and spiritual needs of both the person with Parkinson’s and those closest to them.

Identification of the unmet palliative needs of the person with Parkinson’s through frequent reassessment by the multidisciplinary team.

Identifying prognostic indicators which show relevant deterioration of the person’s Parkinson’s and may be indicative of nearing the end of life.

Timely referral to specialist palliative care services, which have the expertise and experience to manage the complex care needs that may arise. Because of the fluctuating nature of Parkinson’s, it may be necessary for specialist palliative care input several times throughout the condition’s trajectory.

Advance care planning (ACP) – it is important for the health professional to identify and be sensitive to indicators that the person with Parkinson’s or their family want or need to have a discussion about prognosis or future care.

In some ways, our approach to these challenges is brought together through advance care planning (ACP). Here we look at ACP in greater detail due to its importance in delivering person-centred end of life care. Advance care planning has been identified as an area of palliative care which is NOT consistently occurring and often takes place too late in the condition.

This is especially important in Parkinson’s, as the high incidence of cognitive deterioration and dementia can mean a person with Parkinson’s may not be able to express their desired preferences for their future or end of life care if ACP is not initiated early in the condition.

Research has shown that advance care planning will enhance the quality of care for that person and those closest to them (Detering et al, 2010).

Therefore, it is important for you to identify and be sensitive to indicators that the person with Parkinson’s, or their family, want or need to have a discussion about prognosis and future care.

Initiating this conversation at the appropriate time will allow the person with Parkinson’s to receive timely information, enabling them to:

- make informed decisions about their future care

- have realistic expectations

- avoid inappropriate burdensome interventions at the end of life

With the permission of the person with Parkinson’s, this discussion needs to be documented, regularly reviewed and communicated to key people involved in their care (The Irish Palliative Care in Parkinson’s Disease Group, 2016).

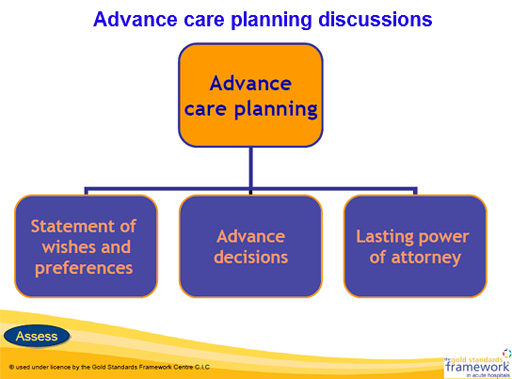

3.3 What is advance care planning (ACP)?

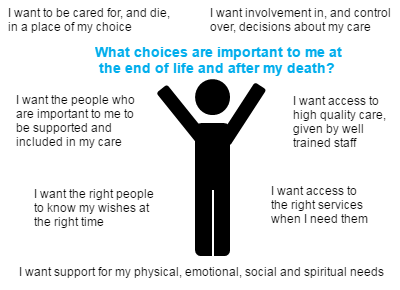

The above diagram represents the topics covered during an ACP discussion.

This is an ongoing process of discussion between the person with Parkinson’s, those closest to them and their health and social care professionals, focusing on the person’s wishes and preferences for their care over the condition’s trajectory and as they approach the end of their life.

Advance care planning may include:

The individual’s concerns and wishes.

Their most important values or personal goals for care.

Their understanding of their illness and the prognosis.

Their psychological and spiritual requirements.

Their preferences and wishes for types of care and place of care if they are not able to look after themselves.

Expressed views on organ or tissue donation.

Their preferences regarding the type of treatment that may be beneficial in the future and the availability of these treatments.

You can find more detail in Advanced Care Planning: A Guide for Health and Social Care Staff.

NHS Scotland has also produced an Anticipatory Care Planning Toolkit.

Documentation of ACP

It is important that you are sensitive to the person’s feelings and desires to have this conversation and so should avoid following a prescriptive method of interviewing and recording these discussions.

There is no set format for making a record of ACP discussions, but some health trusts and charities may be able to provide an informal document for the individual to use.

For example Gold Standards Framework provides guidance information and direction on ACP and this includes a document that allows the person to record their preferences and priorities for their future care.

The ACP is not a legally binding document, but must be taken into account when acting in the person’s best interests.

It must be reviewed and updated as the individual’s situation or views change. In accordance with the client’s wishes a copy of the ACP may be held in the client’s healthcare/electronic notes. The GP and family may be aware of the contents and where it is stored.

The timing and context of ACP

ACP may be initiated by either the health and social care professional or the individual, and may be prompted by one of the following life events:

- Death of a spouse, close friend or relative.

- Following diagnosis with Parkinson’s.

- Significant shift in treatment focus, eg treatment less effective or fewer options.

- Multiple hospital admissions.

The health and social care professional initiating this conversation should have full knowledge of the individual’s medical condition, treatment options and social situation.

Reflective exercise

So far in section 3 we have discussed the challenges of predicting the end of life and discussed advance care planning. Consider this information as you read through this case study about Suzi, a young mother with Parkinson’s, and consider how you would commence a conversation about ACP.

You can record your thoughts in your reflection log.

Case study

Suzi was diagnosed with Parkinson’s four years ago. She is married and has two children. She has been working full time as a hairdresser, and manages her home and young children, aged 6 and 4. Recently, her condition has deteriorated. She has developed anxiety and any stressful situation increases her anxiety and exacerbates her tremor. Her clients have commented on Suzi’s hand tremor and this increases her anxiety.

She has lost strength and volume in her voice and finds it difficult to communicate at work. She suffers increased fatigue after her day at work and feels this affects her relationship with her children, as she is too tired to interact and play with them. Due to these changes, Suzi has become quite self-conscious and no longer wants to socialise as much, especially with strangers.

Reflection 1

Reflect on the case study and note the issues that Suzi is experiencing and decide how you would assist her to overcome these issues.

Use the reflection log to record your thoughts

Discussion

In your reflection you may have considered the following:

Referring Suzi to the appropriate allied health professionals to assist her to manage her increasing symptoms, such as:

- Speech and language therapist for speech management.

- Occupational therapist to assist with work related issues and fatigue.

- Community psychiatric nurse, psychologist or occupational therapist to teach her coping strategies for her anxiety.

- Neurologist to reassess her medication.

It will also be necessary to involve her husband and discuss his involvement in childcare to ease Suzi’s stress.

Reflection 2

Reflect on what you have just read about commencing discussions on ACP, then write a paragraph with an argument for or against commencing an ACP discussion with Suzi and her husband at this stage.

Use the reflection log to record your thoughts

Discussion

In your reflection you may have considered the following:

It would be an appropriate time to encourage this couple to think about how Parkinson’s is progressive, and that Suzi’s ability will slowly deteriorate, encouraging them to discuss their changing roles in the future. The advance care planning (ACP) discussion could centre around the idea of involving the extended family in Suzi’s care in the future, if this is what they would wish. Encourage them to discuss making a Will for the safekeeping of their children. When discussing the Will encourage them to think about power of attorney. An ACP discussion at this stage will promote realistic expectations for Suzi’s future.

ACP promotes person-centred care throughout the condition’s trajectory.

Research and client experience has shown these discussions can never take place early enough, and they will improve client care outcomes.

Some of you may argue that Suzi is too young for discussions about ACP, and that discussing the progressive nature and increasing disability of Parkinson’s at this early stage may cause Suzi and her husband more distress and anxiety. She is in the early stages of her condition and with medication, exercise and support she will continue to manage. Discussing ACP may cause her to lose hope and maybe experience depression, and be psychologically less able to manage.

The discussion around advance care planning may lead to the individual recognising, if they were no longer physically or mentally able to make decisions about their finances or property, that they may need to consider appointing an attorney.

3.4 What is lasting power of attorney?

This is a legal document which must be drawn up by a solicitor, and allows the individual who has the capacity to do so, to choose other people to make decisions on their behalf. There are 2 types of lasting power of attorney (LPA):

- health and welfare

- property and financial affairs.

People can choose to make one type of LPA or both.

You can read more in the UK government’s overview about power of attorney.

Lasting power of attorney will be applicable only if the individual:

- loses mental capacity to make their own decisions about their finances and property, and health and welfare

- or if they are no longer physically able to manage their financial affairs, and health and welfare.

Health and welfare lasting power of attorney

An individual uses this LPA to give an attorney the power to make decisions about things like:

- daily routine, eg washing, dressing, eating

- medical care

- moving into a care home

- life-sustaining treatment.

It can only be used when the individual is unable to make their own decisions.

Property and financial affairs lasting power of attorney

An individual uses this LPA to give an attorney the power to make decisions about money and property, eg:

- managing a bank or building society account

- paying bills

- collecting benefits or a pension

- selling a home.

It can be used as soon as it’s registered, with the individual’s permission.

3.5 What is an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment?

During the course of an individual’s advance care planning (ACP) discussion they may indicate that they wish to make an advance decision to refuse certain treatments.

This is a separate document to that of the ACP and must be instigated by a professional who is competent in this process. They are required to follow the guidance available in the Code of Practice for the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) on Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland professionals must follow guidance available in the Adults With Incapacity Act (2000).

- An Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment allows the person who is 18 years of age or over to specify (before loss of capacity) what treatments they would not want and would not consent to later in life. In Scotland the age of advanced directives is 16. They cannot demand certain treatments or refuse basic care, ie offers of food and water by mouth, warmth, shelter and hygiene. But clinically assisted nutrition and hydration given by intravenous, subcutaneous or gastroscopy are considered medical interventions and can be refused. These decisions can be withdrawn if the individual gains or retains capacity.

- All healthcare providers must respect the individual’s advance decision and ensure it is incorporated into the person-centred care planning. They will also have discussed who is to be made aware of the ADRT (ie family members) and where they wish to store it in the home. A copy of the document should be stored in their healthcare notes and their GP made aware.

The following table (you need to click the link 'view large table') shows the differences between general care planning and decisions made in advance. It explains the who, what and how of the procedures necessary to activate advance care planning (ACP), Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) and Do Not Attempt CPR (DNA CPR).

| General Care Planning | Advance Care Planning (ACP) – advance statement | Advance Decisions to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) | Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) | |

| What is covered? | Can cover any aspect of current health and social care. | Can cover any aspect of future health and social care. | Can only cover refusal of specified future treatment. May be made as an option within an advance care planning discussion. | Only covers decision about withholding future CPR. |

| Who completes it? | Can be written in discussion with the individual who has capacity for those decisions. OR Can be completed for an individual who lacks capacity in their best interests. | Is written by the individual who has capacity to make these statements. May be written with support from professionals, and relatives or carers. Cannot be written if the individual lacks capacity to make these statements. | Is made by the individual who has capacity to make these decisions. May be made with support from a clinician. Cannot be made if an individual lacks capacity to make these decisions. | Completed by a clinician with responsibility for the patient. Patient consent is sought only if an arrest is anticipated and CPR could be successful. Can be completed for an individual who does not have capacity if the decision is in their best interests. |

| What does it provide? | Provides a plan for current and continuing health and social care that contains achievable goals and the actions required. | Covers an individual’s preferences, wishes, beliefs and values about future care to guide future best interest decisions in the event an individual has lost capacity to make decisions. | Only covers refusal of future specified treatments in the event that an individual has lost capacity to make those decisions. | Documents either:

|

| Is it legally binding? | No – advisory only. | No – but must be taken into account when acting in an individual’s best interests. | Yes – legally binding if the ADRT is assessed as complying with the Mental Capacity Act and is valid and applicable. If it is binding it takes the place of best interest decisions about that treatment. | Yes – if it is part of an ADRT. Otherwise it is advisory only, ie clinical judgement takes precedence. |

| How does it help? | Provides the multidisciplinary team with a plan of action. | Makes the multidisciplinary team aware of an individual’s wishes and preferences in the event that the patient loses capacity. | If valid and applicable to current circumstances it provides legal and clinical instruction to multidisciplinary team. | Makes it clear whether CPR should be withheld in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest. |

| Does it need to be signed and witnessed? | Does not need to be signed or witnessed. | A signature is not a requirement, but its presence makes clear whose views are documented. | For refusal of life sustaining treatment, it must be written, signed and witnessed and contain a statement that it applies even if the person’s life is at risk. | Does not need to be witnessed, but the usual practice is for the clinician to sign. |

Who should see it? | The multidisciplinary team as an aid to care. | Patient is supported in its distribution, but has the final say on who sees it. | Patient is supported in its distribution, but has the final say on who sees it. | Clinical staff who could initiate CPR in the event of an arrest. |

UK guidance recommends that decisions about CPR are discussed with the patient and family.

In 2014, the Court of Appeal concluded that when a decision about CPR is being considered “there should be a presumption in favour of patient involvement and that there need to be convincing reasons not to involve the patient” and went on to say “However, it is inappropriate (and therefore not a requirement of article 8) to involve the patient in the process if the clinician considers that to do so is likely to cause the person to suffer physical or psychological harm”.

A subsequent High Court ruling in 2015 noted a presumption in favour of involving those close to an adult who lacks capacity, whenever practicable and appropriate.

Further reading

Code of Practice for the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) on Advance decision to refuse treatment

Decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (3rd edition - 1st revision). Guidance from the British Medical Association, Resuscitation Council UK and the Royal College of Nursing 2016

Advance Directives in Scotland by Solicitors for Older People Scotland

Decisions about Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation - Integrated Adult Policy Scottish Government

Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT) - Resuscitation Council UK resources for healthcare professionals

The discussions around ACP and inclusion of types of treatment the individual wishes to have or not have direct the palliative and end of life care in such a way as to improve the individual’s experience at end of life and also that of those close to them.

3.6 Person-centred care

The diagram below depicts the results of the generic narrative for person-centred care, based on literature review, experiences of bereaved carers and views and experiences of professionals and carers. It was produced by National Voices and the National Council for Palliative Care. It supports the type of person-centred care advocated in the principles of end of life care, which were discussed in section 2.4.

It also summarises the elements discussed in section 3, which promote person-centred care at end of life and support the person and those closest to them to have their desired end of life experience.

The following video produced by NHS England discusses person-centred care. It explains the elements of care which produce co-ordinated and seamless care and promote satisfaction and improved care outcomes for the individual.

Further Reading

NICE guideline (NG197) Shared decision making, June 2021

3.7 Summary of section 3

In this section we examined the challenges you face in predicting the end of life in Parkinson’s, and discussed how to manage these challenges.

We then looked at the importance of advance care planning (ACP), including the issues around starting these conversations and what ACP should cover regarding a client’s wishes and preferences about their future care (including discussions about lasting power of attorney and Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment).

We also discussed the importance of person-centred care being fundamental to all healthcare decisions, and the importance of family and carers being involved in any healthcare decisions about the future care of their relative.

Reflective exercise

Use this exercise to assist you to reflect on choices which would be important to you and your family if you knew you were approaching the end of your life.

Reflect on which choices would be important to you if planning your end of life care, and write them in your reflective log.

Discussion

In your reflection you may have considered the following:

What choices are important to me at the end of life and after my death?

- I want to be cared for, and die, in a place of my choice.

- I want involvement in, and control over, decisions about my care.

- I want access to high-quality care, given by well trained staff.

- I want access to the right services when I need them.

- I want support for my physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs.

- I want the right people to know my wishes at the right time.

- I want the people who are important to me to be supported and included in my care.

Quiz questions

Now try Quiz 2.

This is the second of 3 section quizzes. You will need to try all the questions and complete the quiz if you wish to gain a digital badge. Working through the quiz is a valuable way of reinforcing what you’ve learned in this section. As you try the questions you will probably want to look back and review parts of the text and the activities that you’ve undertaken and recorded in your reflection log

4 Management of the end of life phase in Parkinson’s

In the previous section, we explored some of the challenges of managing and predicting the end of life in Parkinson’s, highlighting the need for advance care planning.

In this section, we take a more detailed look at the management of the end of life phase of Parkinson’s. Taking a holistic approach, we look in depth at the management of the physical, psychological, spiritual and social aspects of end of life care. We will highlight the importance of including and supporting the family or those closest to the person with Parkinson’s throughout this end of life phase, and working with the multidisciplinary team to meet their needs.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section you should be able to identify and describe the following:

- The indicators of the end stage of life.

- The 4 areas of end of life care which focus on quality of life.

- The in-depth management of physical, psychological, spiritual and social aspects of the end of life stage.

- The needs of the family and/or carer during the end of life stage.

- The actively dying phase of Parkinson’s and its management.

- The importance of bereavement care for the family and/or carers.

4.1 What are the indicators for the end stage of life?

Making judgements about end of life care in Parkinson’s is complex. The rate of progression and the nature of symptoms experienced is unique to each individual, so person-centred care planning is very important. For care to be effective it needs an integrated multidisciplinary team sharing expertise in planning and delivering individualised, co-ordinated and seamless care. Each professional within the multidisciplinary team brings their own expertise to the palliative care process and may have been involved with the individual along the trajectory of their Parkinson’s.

Managing the end stage of life in Parkinson’s may involve the last few years of the life of the person with Parkinson’s in which life-prolonging therapy is replaced by palliative measures. The person with Parkinson’s may experience multiple acute episodes of physical disability and cognitive decline either related to Parkinson’s or other comorbidities. Each professional will now find there is a shift in the emphasis of care in the end of life stage, from a therapeutic pharmacological approach to one that places greater emphasis on quality of life issues.

The Gold Standards Framework has developed prognostic indicator guidance for Parkinson’s. The table below explains that the presence of two or more symptoms from any of the categories indicate the end stage of Parkinson’s.

DRUG TREATMENT Decreasing response to medications. Increasingly complex regimen of medications. | INDEPENDENCE Declining physical function, limited self-care. Increasing need of help for daily living. In bed or chair over 50% of day. |

CONTROL Parkinson’s becoming less controlled. Less predictable with ‘off’ periods. Repeated unplanned or crisis hospital admission. Significant comorbidities. | SWALLOWING Dysphagia leading to recurrent aspiration pneumonia, breathlessness or respiratory failure. Significant weight loss of more than 10% of body weight in last six months. Dysphasia (progressive communication problems). |

MOVEMENT Increasing ‘off’ periods. Deteriorating mobility with increasing falls. | NEURO PSYCHIATRIC SIGNS Deteriorating cognitive function. Depression and increasing anxiety. Hallucinations. |

Footnotes

(Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2010. These guidelines are now archived, but we consider the information above to still be relevant.)4.2 Developing a holistic approach

Utilising the principles of end of life care highlighted earlier in section 2.4 of this course, we will examine how to effectively manage and guide the person with Parkinson’s, and those closest to them, through this end stage with the minimum of distress.

Promoting holistic assessment which respects the autonomy and choice of the person with Parkinson’s is important and involves them in planning their end of life care through early discussions about advance care planning (ACP) and Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT), as discussed in section 3.3

Holistic assessment in the end of life stage focuses on the physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects of care for the person with Parkinson’s. We will examine these in greater depth.

4.3 The management of physical symptoms

Early identification and management of physical symptoms in end of life care are an important element of holistic care.

The EEMMA acronym (Twycross and Wilcock, 2002) may be a useful tool to ensure early identification and management of physical symptoms. It involves the individual’s contribution to the care management of each symptom and ensures client satisfaction, autonomy and dignity.

E – Evaluation – make a clear and accurate assessment of each symptom.

E – Explanation – to the individual and/or family on the cause and possible treatments.

M – Management – an individual treatment plan should be formulated in consultation with the person with Parkinson’s and/or family.

M – Monitoring – each symptom should be continuously reviewed and adjustments in treatments made.

A – Attention to detail – make use of the expertise of the multidisciplinary team and other appropriate experts, eg the specialist palliative care team.

Another option of symptom measurement is the Palliative care Outcome Scale.

The overall management of both motor and non-motor symptoms relies on a comprehensive, holistic assessment by the multidisciplinary team, with the appropriate referral to specialist palliative care professionals.

Assessment can be time consuming, due to communication and cognitive issues, but with the use of patient-centred care planning, the person with Parkinson’s and those most important to them will experience high-quality end of life care.

4.3.1 Pain

Pain is a key symptom of Parkinson’s. The priority is to regularly assess and monitor for pain or discomfort. It must not be assumed that all pain is Parkinson’s related as it may be due to other reasons, perhaps related to comorbidities.

Questioning the individual about their pain and listening carefully to their description will permit the professional to judge the type of pain and its appropriate management.

Non-verbal indices of pain such as groaning, agitation or tearfulness need to be considered if the individual has limited communication, and visual pain scales can also be useful in these situations.

Further reading

The following link provides examples of a number of pain scales: Pain assessment scales (National Initiative on Pain Control, 2005).

Exercise for reflective practice

In your reflection log briefly discuss the type of guidance or care plans that are used in your area to direct and ensure good practice in identification and management of physical symptoms. Are they similar to the EEMMA acronym, or are they different but more appropriate to the clients you are caring for?

Non pharmacological and pharmacological management of pain

- Non pharmacological management: In advanced Parkinson’s this type of management is important to prevent exacerbation of hallucinations or decline in cognitive ability. It is also important when swallowing is compromised. This involves therapies such as limb massage, physiotherapy positional/postural changes, pressure relieving devices, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and acupuncture.

- Pharmacological interventions: A three-step analgesic ladder developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for management of cancer-related pain is frequently used as a framework for prescribing analgesic pain relief. This three-step approach of administering the right drug at the right time is inexpensive and 80-90% effective. However, some studies report 70-80% and there is a question about whether the WHO analgesic ladder is still valid.

The specialist palliative care team may be involved to manage more complex pain or to offer guidance about the most effective route of administration, ie subcutaneous or parenteral, taking into account the needs of the individual and their choices when possible.

Most analgesia increases the risk of constipation. Careful monitoring of bowel function and titration of laxatives are important to maintain optimal absorption of Parkinson’s medication and the person’s comfort.

Further reading

Analgesic ladder (World Health Organization, 2017)

NICE guideline [CG140] 2012 Palliative care for adults: strong opioids for pain relief. Updated 2016

4.3.2 Other types of pain

Dyskinesia may occur during ‘off’ periods in the end stage of Parkinson’s if the person has been on long-term levodopa therapy.

This can be managed with reduction of the levodopa dose, but this alone may cause worsening of parkinsonism symptoms and increasing frequency of ‘off’ periods, so a monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) or catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor may be added if there are no contraindications for their use. If contraindicated, memantine has been helpful in reducing dyskinesia (Varanese et al, 2010).

If a person with Parkinson's has developed dyskinesia and/or motor fluctuations, including medicines 'wearing off', seek advice from a healthcare professional with specialist expertise in Parkinson's before modifying therapy.

Offer a choice of dopamine agonists, MAO-B inhibitors or COMT inhibitors as an adjunct to levodopa for people with Parkinson's who have developed dyskinesia or motor fluctuations despite optimal levodopa therapy, after discussing:

- the person's individual clinical circumstances, eg their Parkinson's symptoms, comorbidities and risks from polypharmacy

- the person's individual lifestyle circumstances, preferences, needs and goals

the potential benefits and harms of the different drug classes.

If dyskinesia is not adequately managed by modifying existing therapy, consider amantadine.

Neuropathic pain is common in Parkinson’s, indicated by a description of sensory symptoms such as numbness or paresthesia and with a burning or radiating pain.

Neuropathic pain is treated with anticonvulsant agents, such as gabapentin and pregabalin, and antidepressants, such as amitriptyline or duloxetine.

In the dying phase of care the individual will most likely not be able to report pain directly, but monitoring the non-verbal indices will guide the family and health professional of the need for analgesia.

Rigidity/stiffness in advanced Parkinson’s may be the result of a variable response to dopaminergic medication, and increased intolerance due to associated neuropsychiatric complications.

Rigidity will usually affect the limbs causing associated pain.

It is difficult at this advanced stage to balance treatment for rigidity without increasing or causing agitation, hallucinations or somnolence.

To lessen rigidity, ensure dopaminergic medication is given on time according to the individual’s usual regimen. In addition to their usual regimen, use doses of dispersible levodopa/benserazide (or rotigotine transdermal patches if their swallow is compromised).

If a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is already in situ, this would be used to administer medication. If not in place, administer by nasogastric (NG) tube, which would only be considered as a short-term solution.

If a person with Parkinson’s is on an apomorphine pump at the end stage of life, it may be appropriate to maintain the infusion to prevent rigidity and pain. But if the person has suffered weight loss or is experiencing side effects, it may be appropriate to lower the rate as guided by the consultant.

In the dying phase of care there may come a time when it is impossible to administer oral medications and transdermal rotigotine patches are contraindicated due to increased agitation or hallucinations. In these circumstances, the administration of midazolam in a subcutaneous infusion, under the guidance of the specialist palliative care team, may be effective in treating rigidity.

4.3.3 Communication, speech and language difficulties

At end stage of Parkinson’s the individual may suffer a combination of hypophonia and dysarthria, which causes communication problems and difficulties being understood. It is important to assist the person with Parkinson’s to have an effective alternative method for communication, to lessen their frustration and allow expression of their fears or anxieties.

DYSPHAGIA

Dysphagia may be associated with an increasing risk of silent aspiration at this stage of the condition, so the speech and language therapist will educate the person with Parkinson’s and family and/or carers in how to manage this (Kaif et al, 2012).

SIALORRHEA