Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:27 PM

Section 1: Gender stereotypes and equality

Introduction

In this section we will look at:

- The course aims

- The structural nature and harm of gender inequality and stereotyping

- The causes of female underrepresentation in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM)

Learning outcomes for Section 1

By the end of this section you will have

- An overview of the course aims

- Explored the structural nature and harm of gender inequality and stereotyping

- Explored the causes of female underrepresentation in STEM

- Reflected on your own practice and classroom experience

Before you start on section 1.1 you should download your learning log. How you use the log is up to you. You can save it and work with it online or print it off and keep it up to date in hard copy.

Throughout the course you will be prompted to record your responses to individual and group activities and your reflections. The log provides a record of your learning that you can use in developing classroom activities and for professional update.

Course aims

This course aims to reduce barriers for participation in STEM subjects by female students through challenging gender stereotyping and building STEM capital in the classroom, using an enquiry based approach. This online OER is designed not only to deliver information but to contribute towards transformational change in schools.

Activity 1

You should start by noting down what you hope to achieve in studying this module

Discussion

For example:

I want to break down perceptions of what is a boy’s subject and what is for girls?

I want to be able to challenge perceptions of what boys and girls can do.

I want to help to change the culture of my school in relation to gender stereotypes.

I’d like to understand why so few young women from my school go on to further study or employment in STEM

I want to develop some new ideas for encouraging my female pupils to have a positive attitude to STEM

I want to build my confidence to address unconscious bias and gender stereotyping in the classroom.

Safeguarding information

Talking about gender and the way it affects our lives can bring up some difficult issues, memories, and feelings. Although this online open educational resource and suggested classroom activities are not focused on personal experiences, it may lead to disclosures which amount to wellbeing concerns about pupils.

School policies: Before beginning this course you should re-familiarise yourself with your school’s related policies, including child protection, and make sure you are familiar with who your schools’ designated Child Protection Officer is. Children and young people involved in the activities associated with the course should be informed that you will pass on any concerns you have about their safety.

Signposting: There are many organisations set up to support children and young people with related issues. Before beginning the course find out about local services which you can signpost to as needed, for example, ChildLine, your local Rape Crisis centre, LGBT Youth Scotland.

Dealing with sexism in your classroom and school: Through this course and the classroom activities you may become aware of sexist behaviour in your school classrooms. Thinking in advance about how you with deal with this and discussing it with colleagues will be helpful. If faced with sexist behavior from a student it can be helpful to make a value statement such as “using that word(s) to put someone down is unacceptable”. Help them challenge the reasoning behind their words with questions such as “what makes you think that?” or “what do you mean by that?”. Learning to recognise and challenge everyday sexist behavior of staff and pupils is an integral part of contributing to positive culture change.

Sexual harassment and bullying at school: Recent research shows that sexual harassment and bullying at school is widespread. Sexual harassment and bullying is a cause and consequence of gender inequality. Girlguiding Scotland’s 2014 Girl’s Attitude Survey revealed that 59% of girls aged 13 to 21 faced sexual harassment at school or college, and 22% of girls 7-12 had experienced jokes of a sexual nature from boys at school. The Scottish Parliament’s Equalities and Human Rights Committee has recently published a report It is not Cool to be Cruel on children’s experiences of prejudice-based bullying and harassment with recommendations including teacher training and changes to the curriculum.

Dealing with disclosures: Pupils may disclose something related to sexism, sexual harassment or abuse, in a group setting or to you individually in response to the classroom activities. Some general principles for dealing with a disclosure are:

- Stay calm and listen carefully

- Explain that you might need to pass on concerns

- Let the child set the pace, don’t ask lots of questions

- Provide reassurance and explain what will happen next

- Get advice and support for you, if needed.

Preparing for what might come up: Before conducting classroom activities it may be helpful to think through and discuss with colleagues in your study group what kind of issues may come up and how you will deal with them.

1.1 Introduction to Gender Inequality

To begin the course we are going to explore what we mean when we talk about ‘gender’. To start us off let’s think about the differences between ‘gender’ and ‘sex’.

Activity 2 – What is Gender?

Can you identify the correct definitions for each of the following?

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 4 items in each list.

Sex

Gender

Gender roles

Gender identity

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Refers to the socially constructed roles, behaviours, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for men and women. This and the related power relations are a social construct – they vary across cultures and through time, and thus are amenable to change.

b.A person’s deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond with the sex assigned to them at birth. This may include people who would identify as agender, non-binary, transgender or gender fluid. This can include having two or more genders, having no genders, moving between genders, or having a fluctuating gender identity.

c.Refers to the biological and physiological characteristics that define men and women. At the same time, it may not always be possible to define along the dichotomous lines of male-female only, as is made evident by inter-sexed individuals.

d.The particular economic, social roles and responsibilities considered appropriate for women and men in a given society. These do not exist in isolation, but are defined in relation to one another and through the relationship between women and men, girls and boys.

- 1 = c,

- 2 = a,

- 3 = d,

- 4 = b

Sources:

Medical Women's International Association (MWIA), Training Manual for Gender Mainstreaming in Health, 2002, pp 10, 19; UN Women, Gender Mainstreaming – Concepts and Definitions

www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/conceptsanddefinitions.htm;

World Health Organization, Gender, women and health, www.who.int/whatisgender/en. https://www.lgbtyouth.org.uk/yp-transgender

Gender equality

UN Women define gender equality as:

“The equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and menand girls and boys. Gender equality implies that the interests, needs and priorities of both women and men are taken into consideration, recognising the diversity of different groups of women and men (for example: women belonging to ethnic minorities, lesbian women or women with disabilities). Gender equality is a human rights principle.”

Gender Inequality

Despite progress being made toward achieving equal rights; women and girls in the UK continue to experience inequality, discrimination and harassment, and face significant barriers to achieving their full potential. The daily experience of gender inequality ranges from undermining portrayals of women in the media and underrepresentation of women in positions of power, to direct discrimination and breaches of their human rights. Social expectations and assumptions about the abilities, roles and opportunities which should be afforded on the basis of gender continue to define the life chances of women today.

1.2 Structural gender inequality

Structural gender inequality refers to the structures in society which contribute to men enjoying more advantage, power and privilege than women through how society is organised. Some examples of this are below:

Pay Gap

Despite the Equal Pay Act coming into force in 1970, women still earn less than men in the UK today. (https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/ close-gender-pay-gap)

Activity 3

Why does this matter? – write down your reflections about why the pay gap matters in relation to gender equality

Discussion

When some women are paid less than men for the same work this is discriminatory undervaluing of a person’s work based on their gender. Recent research shows that unfair treatment of women remains common, especially around maternity. For example, 54,000 women are forced to leave their job early every year as a result of poor treatment after they have a baby. (Fawcett Society)

Care Gap

Women continue to play a greater role in caring for children, as well as for sick, disabled or elderly relatives. (http://www.carersuk.org/ for-professionals/ policy/ policy-library/ the-importance-of-carer-s-allowance)

Activity 4

Why does this matter? – write down your reflections about why the care gap matters in relation to gender equality.

Discussion

As a result of caring responsibilities more women work part time and these jobs are typically lower paid with fewer progression opportunities (Fawcett Society). Women are twice as likely as men to give up paid work to care (Engender Scotland). Twice as many female carers rely on benefits than male carers, at a rate of £1.55 per hour (Carers Scotland). These factors all lead to reduced income and reduced opportunities for women, and continue to feed the cycle of inequality.

Income Gap

Women are still more likely to be in lower paid and low skilled jobs, affecting labour market segregation. (https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/ close-gender-pay-gap)

Activity 5

Why does this matter? – write down your reflections about why the income gap matters in relation to gender equality.

Discussion

Twice as many women rely on benefits and tax credits as men. Gender stereotypes, unconscious bias, increased caring responsibilities, and discrimination all have a knock-on effect on women’s access to the labour market, and means women are disproportionately affected by cuts to benefits and services. Women’s poverty is also inextricably linked to children’s poverty.

Power Gap

Women have unequal access to power, decision-making and participation throughout all areas of public life. (https://www.engender.org.uk/ content/ publications/ SEX-AND-POWER-IN-SCOTLAND-2017.pdf)

Activity 6

Why does this matter? – write down your reflections about why the power gap matters in relation to gender equality.

Discussion

The majority of those in senior positions of authority in Scotland are men – including senior police officers (93%), sheriffs (77%), newspaper editors (100%), directors of FTSE 100 firms (100%) and university principles (74%) This means women are not able to participate fully in society and to exercise equal citizenship as men when they do not have the same access to opportunities. (Engender, 2017)

Representation Gap

Today, despite making up 52% of the population in Scotland, women only make up 36% of public boards, fewer than 35% of MSPs and 24% of Councillors. (Women 50:50 campaign)

Activity 7

Why does this matter? – write down your reflections about why the representation gap matters in relation to gender equality.

Discussion

Every decision made at these levels impacts our daily lives and so people impacted by these decisions should be around the decision making table. Women's lived experiences need to be included in these decisions, as do disabled people, black minority ethnic people, LGBT people, carers, young people, and immigrants. When women are missing from these roles and from public life, not only does their status diminish in society but we allow young people (particularly girls) to perceive that leadership and politics is not for them; you cannot be what you cannot see. (Women 50:50 campaign)

Freedom and Safety Gap

Women and girls are at a significantly higher risk of interpersonal and gender-based violence limiting their freedom of movement and personal safety. (https://beta.gov.scot/ publications/ equally-safe/)

Activity 8

Why does this matter? – write down your reflections about why the freedom and safety gap matters in relation to gender equality.

Discussion

Violence against women and girls is a cause and consequence of gender inequality. Violence against women and girls (including domestic abuse, coercive control, stalking, harassment, sexual assault, female genital mutilation, forced marriage and non-consensual sharing of intimate images) can have a profound impact on all areas of a woman’s life. From preventing a woman from accessing education and employment, isolation from social communities, undermining confidence and self-efficacy, and causing physical and psychological harm – violence and abuse prevent women from exercising their equal rights in all spheres of society.

Activity 9

How aware are you of levels of gender inequality in the UK? Add your best guess to the questions below:

| Question | Your guess |

| What is the current UK overall pay gap between men and women for full time workers? | |

| What percentage of those who receive Carer’s Allowance in UK are women? | |

| What percentage of lone parents, dependent on income support in UK, are women? | |

| What percentage of women in UK have experienced some form of domestic violence, sexual assault or stalking? | |

| What percentage of people in UK earning less than the living wage are women? | |

| What percentage of cuts to social security will have come from women’s incomes between 2010 and 2020 in UK? | |

| What percentage of MPs are women? (since June 2017 election) | |

| How many years is it estimated to take before we see a gender-balanced UK parliament? | |

| What percentage of those working in the low paid care and leisure sector are women? | |

| What percentage of those working in STEM occupations (which are generally higher paid) in UK are estimated to be women? |

Answer

| Question | Answer |

| What is the current UK overall pay gap between men and women for full time workers? | 13.9% |

| What percentage of those who receive Carer’s Allowance in UK are women? | 72% |

| What percentage of lone parents, dependent on income support in UK, are women? | 95% |

| What percentage of women in UK have experienced some form of domestic violence, sexual assault or stalking? | 45% |

| What percentage of people in UK earning less than the living wage are women? | 60% |

| What percentage of cuts to social security will have come from women’s incomes between 2010 and 2020 in UK? | 86% |

| What percentage of MPs are women? (since June 2017 election) | 32% |

| How many years is it estimated to take before we see a gender-balanced UK parliament? | 50 |

| What percentage of those working in the low paid care and leisure sector are women? | 80% |

| What percentage of those working in STEM occupations (which are generally higher paid) in UK are estimated to be women? | 21% |

(Sources:

https://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk/policy-research/the-gender-pay-gap/;

Carers UK (2015) The Importance of Carer’s Allowance http://www.carersuk.org/ for-professionals/ policy/ policy-library/ the-importance-of-carer-s-allowance;

Engender (2017) https://www.engender.org.uk/ content/ publications/ SEX-AND-POWER-IN-SCOTLAND-2017.pdf;

Scottish Government, https://beta.gov.scot/ publications/ equally-safe/

Women’s Budget Group (2016) The impact on women of the 2016 Budget;

Walby, S & Allen, J (2004);

Women 50:50 campaign;

https://www.wisecampaign.org.uk/ resources/ 2016/ 11/ women-in-the-stem-workforce-2016 )

1.3 Gender inequality and childhood

Structural gender inequality affects even our youngest citizens and is played out daily, for example in the toys, clothes and expectations given to babies.

Read this excerpt from Sciencegrrl (The case for a gender lens in STEM) and think about the content in relation to your classroom environment.

Our society isn’t neutral, it is highly gendered. The reason these hurdles are invisible is that they are so deeply embedded. We must look through both eyes to detect the unconscious biases that permeate our society, homes, classrooms and workplaces before we can start to dismantle them. Empowering individuals with real choice and freeing ourselves from social stereotyping and cultural expectations is better for girls and women, but also for boys and men.

Young women receive messages about themselves and the opportunities available to them from wider society, family and friends, the classroom and the workplace. The balance of these messages is crucial. The ‘girls’ toys’ that value physical perfection over adventure or intelligence, and the objectification of women in the media are just two examples of how the roles and capabilities of women are diminished in wider society. We are all exposed to these messages. Casual reliance on such stereotypes leads to unconscious bias in all areas of girls’ lives. If this is left unchallenged, girls and young women find their cultural straightjackets tightened and they are less likely to say ‘YES’ to STEM. Stereotypes and unconscious bias undermine real choice. We must start to take them seriously.

…the need to challenge pervasive unconscious biases and stereotypes is largely only ever given lip service – if that. Undermining cultural messages and social norms represent invisible roadblocks to the success of girls and women. Such barriers are invisible precisely because they are so deeply embedded. Today, girls and women are told they can be whatever they want. They are hearing the words (Ofsted 2011) but how can we expect them to heed the message when we still talk about a ‘working mum’ but not a ‘working dad’? When women are narrowly represented in the media and the toys children are given are gendered so that girls toys are more likely to reinforce domestic duties and physical perfection, whilst the boys get action roles and adventure challenges?

In your Learning Log write down your first reactions to this article. Does it chime with your experience? Are there aspects of gender inequality that it excludes? How does it relate to the experience of young women in the education system? Leave your answers for a while and then come back and think again about what you’ve read. What barriers or roadblocks can you think of in relation to gender equality in STEM?

Your learning log is personal and confidential, however you may wish to make a note of questions about Science Grrl’s post that you would like to share and discuss with colleagues in your study group.

So what can we do about it?

As we’ve seen gender impacts every single area of our lives even from an early age, but much of this remains accepted or hidden in our society. In order to begin to address inequality we need to learn to see and identify it.

Applying a Gender Lens

Against this background of persistent gender inequality, Science Grrl argues that:

Despite being in an age of challenging gender roles, we still live with the echoes and reality of a patriarchal culture. Recognition of patriarchy (a social order in which men are the primary holders of power and decision making) is not an accusatory statement. It is necessary to look at long-held systems through a gender lens to make real progress towards real equality.

(Science Grrl, The case for a gender lens in STEM)

The UN recognizes the importance of developing and applying a ‘gender lens’:

‘Think of the gender lens as putting on spectacles. Out of one lens you see the participation, needs and realities of women. Out of the other you see the participation, needs and realities of men. Your sight or vision is the combination of what both eye sees.’ – UNESCO (2006)

Using a gender lens enables us to identify where genders are treated differently and to address gender inequality. We have to remind ourselves and train our minds to recognise the different ways girls and boys experience our classrooms and schools and the differences in interactions that take place. Noticing these differences and how different treatment and experiences lead to different outcomes is a crucial first step towards putting in place initiatives or changes that will lead to gender equality.

One of the first steps in applying a gender lens is understanding gender stereotypes.

1.4 What is gender stereotyping?

This United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner defines gender stereotyping as:

“A gender stereotype is a generalised view or preconception about attributes or characteristics that are or ought to be possessed by, or the roles that are or should be performed by women and men. A gender stereotype is harmful when it limits women’s and men’s capacity to develop their personal abilities, pursue their professional careers and make choices about their lives and life plans. Harmful stereotypes can be both hostile/negative (e.g. women are irrational) or seemingly benign (e.g. women are nurturing). It is for example based on the stereotype that women are more nurturing, that child rearing responsibilities often fall exclusively on them.”

Gender stereotyping refers to the practice of ascribing to an individual woman or man specific attributes, characteristics or roles by reason only of her or his membership in the social group of women or men. Gender stereotyping is wrongful when it results in a violation or violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms. An example of this, is the failure to criminalize marital rape based on societal perception of women as the sexual property of men.

Compounded gender stereotypes can have a disproportionate negative impact on certain groups of women, such as, women in custody and conflict with the law, women from minority or indigenous groups, women with disabilities, women from lower caste groups or with lower economic status, migrant women.

International human rights law places a legal obligation on States to eliminate discrimination against women and men in all areas of their lives. This obligation requires States to take measures to address gender stereotypes both in public and private life as well as to refrain from stereotyping. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) provides in its article 5 that, “State Parties shall take all appropriate measures to modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customs and all other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either of the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women.” Other human rights treaties also require States Parties to address harmful stereotypes and the practice of stereotyping. For example, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) also contains in article 8(1)(b) obligates States to combat stereotypes and stereotyping, including compounded stereotypes and stereotyping based on gender and disability.

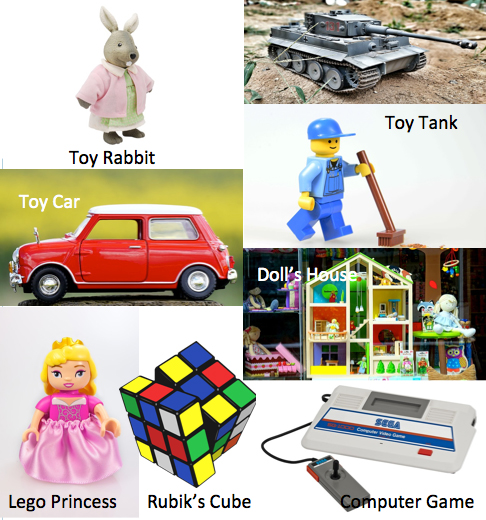

Activity 10

Which of the following images might be stereotypically considered associated with boys or girls, or to be neutral? Write in the boxes below which toys you think belong in which categories:

| Girl | |

| Boy | |

| Neutral |

Discussion

The messages young children receive about gender roles and expectations are heard loud and clear through the books, toys and clothes marketed to children based on gender stereotypes. Young girls are encouraged to be pretty, passive and interested in pink, whereas young boys are encouraged to be strong, brave and interested in blue. It can be challenging to combat these stereotypes when they appear in seemingly harmless forms such as toys and books which are meant to be fun. Removing the labels of “this is for boys” or “this is for girls” and creating an inclusive environment centered around choice is important. Helping children to develop critical skills in questioning why someone’s interests should be limited based on their sex or gender is one way to disrupt the patterns of gender stereotyping and policing in relation to toys, books, and clothes. In turn this skill can be used to challenge gender stereotypes in relation to hobbies, subjects and career aspirations.

1.5 Who does gender stereotyping affect?

Gender stereotyping does not only negatively affect women and girls. Boys’ experiences of gender stereotypes can be harmful in a number of ways including through being taught to suppress emotions, pressure to appear “manly” and strong and to choose subjects and careers in line with stereotypes rather than their interests and potential. There also remains stigma associated with males taking on caring roles, which can create further barriers to boys choosing ‘non-traditional’ subjects and complying with societal expectations informed by stereotypes. Those who identify as gender non-binary or transgender may experience additional layers of social pressure, discrimination and harm as a result of not conforming to stereotypes associated with gender. In short, gender stereotyping negatively affects everyone by limiting expression, development and progression based on assumptions and rigid cultural norms.

Gender stereotypes in school

One of the harms of gender stereotyping is that children learn these cultural norms from a very young age, starting as soon as they are born. This shapes the interests and opportunities pursued by children and often extends to “gender policing” in schools by other children based on stereotypes of what girls and boys should be like.

For instance, while the most comprehensive recent studies show no gender differences in maths ability or any difference in interest in science at a young age, stereotypes about gender and math or science are prevalent across society. Multiple studies show that parents and teachers hold strong stereotypes about gender, maths and science.

1.6 The role of the classroom in challenging stereotypes

The role of schools and classrooms are very important in addressing and challenging the gender stereotypes which children experience from birth. It can either be an environment where these stereotypes are reinforced, or one where children and young people are encouraged to challenge stereotypes and pursue interests based on their personalities and goals, not their gender.

The Attracting Diversity Project run by Robert Gordon’s University looked at the experience of Scottish School students.

Several pupils talked about the traditional roles held by their own family and how this shapes their decisions. “Your mum’s cooking supper and your dad’s out working and comes home, that’s what I think why girls pick Home Economics.”

It is felt that peers often negatively influence decision making. This was particularly evident amongst girls who reported people asking them: “Why do you take Physics? It’s hard, it’s for boys.”

References were made to the different interests and nature of boys and girls and how this impacts on subject choice: “Technological studies is for boys because it is physical”; “Biology is for girls because girls usually take the caring role”; “Chemistry is for boys because they like explosions, dangerous chemicals and acids”; “Home economics is for girls because they like sewing” (RGU Attracting Diversity Project Initial Findings).

FURTHER READING: The Institute of Physics report Opening Doors: A guide to good practice in countering gender stereotyping in schools is a helpful resource about how schools can challenge gender stereotyping.

In your learning log note down any observations of how gender stereotypes operate in your classroom setting?

1.7 Participation of women in STEM

Gender inequality and gender stereotyping exists across all sectors and spheres of society. The rest of the course will focus specifically on the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) sector.

Activity 11

What do you know about the STEM sector?

| Question | Your guess |

| How many construction trade workers are women in the UK? | |

| What percentage of those working in the STEM sector in Scotland are women? | |

| What is women’s participation in STEM estimated to be worth per annum to the Scottish economy? | |

| How many new engineers by 2020 in Scotland are estimated to be needed? | |

| How many women who graduate from university in STEM subjects remain in the industry? |

(Source: www.equatescotland.org.uk/)

Answer

| Question | Answer |

| How many construction trade workers are women in the UK? | 2% |

| What percentage of those working in the STEM sector in Scotland are women? | 25% |

| What is women’s participation in STEM estimated to be worth per annum to the Scottish economy? | £170 million |

| How many new engineers by 2020 in Scotland are estimated to be needed? | 140,000 |

| How many women who graduate from university in STEM subjects remain in the industry? | 27% |

We’ve already noted that there is no gender difference in maths ability and that in early years and through primary school, girls generally have the same interest in science.

However, as school progresses and as pupils get older, girls become far less likely to identify with science and to express ambition to have a STEM career. By the time pupils make subject choices, they have largely opted out of STEM choices. In 2014 in Scotland, girls represented only:

- 7% of entries for Higher in Technological Studies

- 20% of entries for Higher Computing

- 28% of entries for Higher Physics

- 3% of engineering modern apprentices

(Education Scotland, Sept 2015)

It’s not surprising then that women are still underrepresented in STEM sectors, particularly in leadership positions or that the UK has the lowest proportion of female engineers in the EU.

Activity 12

What’s the problem with female underrepresentation in STEM?

Note down what you think is the harm in female underrepresentation in STEM?

Discussion

Underuses women’s potential

Is bad for the economy because the sector is approaching a skills crisis and not recruiting women is a missed opportunity to meet the demand for STEM growth.

Reserves well-paid jobs for men

Perpetuates harmful gender stereotypes

Missed opportunity in addressing skills gap

Limits opportunities for both genders - if only men can work in STEM then they aren’t as likely to work in other professions, such as nursing or teaching

You can read more about the above in this briefing document.

1.8 Stereotypes contribute to barriers to participation

How do stereotypes contribute to barriers to participation for women in STEM subjects and careers? The presence of stereotypes in classrooms and schools seems to lead girls to be less interested in science as they get older and stereotypes keep those girls who are interested from pursuing their dreams. Stereotypes influence our actions through unconscious bias, which we’ll explore further in the next section.

Read the following excerpt from Equate, writing about experiences in Scottish education:

Despite boys and girls having an equal interest in science and technology, by the time girls enter their teen years their interest dramatically falls (regardless of the academic capability in science). Boys are more likely to pursue subjects such as physics, chemistry, engineering and computing. From the age of 15 young women have potentially limited their chances of working in STEM. This is because they are often stereotyped into making certain choices. For the few girls who do pursue subjects such as physics or chemistry it can be an isolating experience when they are potentially the only girl in the classroom, and it runs the risk of putting them off continuing with that subject. (Equate Scotland)

Activity 13

How might gender stereotypes be evident in your classroom or the school environment? Consider the curriculum, activities and interactions and the school culture.

Discussion

- Curriculum: are any female scientists, engineers, mathematicians taught? Are there a wide range of different types of examples, case studies and problems that might appeal to different groups?

- Activities: are girls and boys given equal opportunity and encouragement to explore science, technology, mathematics and engineering activities? How do you know how often girls and boys participate in class or who teachers call on and give encouragement to?

- Culture: do teachers, pupils or parents talk about ‘girl subjects’ and ‘boy subjects’? Are gender stereotypes acknowledged and challenged? How are subject choices and career guidance provided?

How do we begin to address this? (Clue: girls aren’t the problem)

Initiatives that seek to ‘encourage’ girls into STEM are misplaced. The implication is that girls must change. Instead, the responsibility for closing the STEM gender gap should be placed on the people who have influence in our society and education system. Girls are treated differently from boys in the classroom and careers advice is far from inclusive. This separation of girls and young women from the mainstream is the fundamental roadblock (Science Grrl, The case for a gender lens in STEM).

The Institute of Physics has created a poster with top tips for inclusive science teaching. https://education.gov.scot/ improvement/ Documents/ sci38-tips-poster.pdf

Note down in your learning log your reflections about gender stereotypes and inclusive teaching in your classroom setting.

What are the gender demographics of STEM courses/activities in your school?

Is there anything about your practice in the classroom you want to reflect on?

1.9 Intersectionality

Intersectionality recognises that people’s identities and social positions are shaped by multiple factors, which create unique experiences and perspectives. These factors include, among others: gender, race, disability, age, sexuality and religion, as well as socioeconomic status, geographic location or postcode and school attended.

For example, someone isn’t a woman and black, or a woman and white, but a black woman or white woman. These different elements of identity form and inform each other. In this example the person’s identity as a woman cannot be separated from their identity as a black or white individual and vice versa. The experience of black women and the barriers they face, will be different to those white women face. The elements of identity cannot be separated because they are not lived or experienced as separate.

In practice, intersectionality is less about bringing two different things/groups together, for example disabled people and people from lower SES backgrounds and more about considering the experience of disabled people from lower SES backgrounds. These are people at the ‘intersection’ of socioeconomic disadvantage and disability.

We can consider intersectionality in the context of STEM education and stereotypes. For example, the Aspires Report notes that:

“The factors which hinder students from developing science aspirations are amplified in the case of Black students, due to the multiple inequalities they face. This means that science aspirations are particularly precarious among these students ...we also found that the likelihood of a student expressing science aspirations is patterned by gender, social class and ethnicity.” (Aspires report)

In thinking through how you can identify and challenge stereotypes in your classroom, it’s important to think about how we talk about who science is for. This isn’t just about gender, but making sure we are not perpetuating stereotypes about other groups, such as different ethnicities or about socio-economic status. The key message is science should be for everyone.

Activity 14 Quiz 1

You can now try Quiz 1.

Activity 15

Now you’ve completed section 1 take a few minutes to think about what you’ve learnt and what questions and ideas you would like to share with your study group.

Looking back over this section:

What, if anything, surprised you?

What did you learn that was new to you?

What part of the text would you like to discuss further with colleagues in your study group? Note a few questions in your learning log for discussion with your study group.

1.10 Group session: reflecting on the section so far

This section of the course provides an opportunity to reflect, share experiences and discuss the ideas that you have encountered so far. How you do this will depend on the number of people in your study group and the time you have available. As experienced educators you will bring your own ideas and experience to bear on how you organise the discussion.

We suggest that you choose one person to facilitate and another to take notes and share action points at the end of the session. You should allow at least an hour for the session.

In Activity 5, each participant in the study group will have recorded questions and observations in their learning log. If your group is fairly small you may wish to go round the group in turn – each tabling a question and taking time to share perspectives and understanding. In a larger group it’s probably better to pool questions on flip chart and group together similar issues before starting the discussion. In this case breaking into subgroups initially would be a good way to ensure that everyone’s views are heard. You might want to split groups by gender in order to explore differences of experience or you might want mixed groups so that groups can share experiences and build understanding.

1.11 Group session – action planning

The aim of this section is to develop a plan for trying out ideas with your pupils. The learning outcomes for pupils are that at the end of the activities they will be able to:

- Give examples of how gender inequality and stereotypes affect people of school age

- Reflect on their own experience and understanding of stereotypes

- Discuss gender stereotypes in relation to STEM and other subjects

There is one set activity and further suggested outline activities that cover these three learning outcomes and you can download them:

Classroom Activities on gender stereotypes and equality

Working as a group (or in subgroups each with a note taker) consider each activity in turn and look at the following questions.

- Are you clear about the nature of the activity and its relationship to the learning outcomes?

- Does this work? Would you use it? Is it practical?

- What would you do about the issues it raises, during the exercise and afterwards?

- What support do you need to deal with the exercise and afterwards?

- Thinking about your pupils and your context and how you would adapt the activity? In other words take the outline and make it yours.

- Are there any considerations for managing conversations about gender in your classrooms? Will these conversations work well for both boys and girls?

- Decide when you will carry out the activity and with which group.

- Decide how you will evaluate the activity. You might want to collect feedback from pupils or debrief with another member of the study group once the activity is complete.

Further reading and resources

Institute of Physics in partnership with Skills Development Scotland and Education Scotland have produced resources from a three year project to look at the effects of gender on subject uptake and career choice, particularly in relation to STEM. These resources are available on Education Scotland’s National Improvement Hub: https://education.gov.scot/ improvement/ Pages/ sci38-improving-gender-balance.aspx

Action guide for primary schools https://education.gov.scot/ improvement/ Documents/ sci38-primary-action-guide.pdf

Action guide for secondary schools https://education.gov.scot/ improvement/ Documents/ sci38-secondary-action-guide.pdf

Institute of Physics have also produced these 10 tips for teachers on inclusive science teaching https://education.gov.scot/ improvement/ Documents/ sci38-tips-poster.pdf

Reflect in your learning log:

- How did pupils respond to learning about and discussing gender equality and stereotypes?

- Where might gender stereotypes among pupils have an impact on school life?

- Where might gender stereotypes among teachers have an impact on school life?

You can now go to Section 2: Unconscious bias