Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 1:39 PM

2 Curriculum and assessment

Introduction

In this section we will look at:

2.1 Identification pathway and curriculum for Excellence

2.2 Appropriate supports

2.3 Planning

2.4 Reporting

2.5 Learner Profile

2.6 Standardised assessments

2.7 Assessment arrangements

2.8 Transitions

2.9 Suggested Reading

2.1 Identification pathway and Curriculum for Excellence

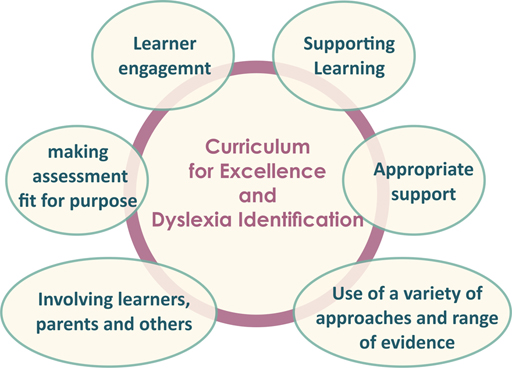

Section 1.2 highlights that the identification of dyslexia, indeed for any additional support needs is not an activity which takes place outwith the principles and practice of Curriculum for Excellence. Figure 8 demonstrates the connectivity and symbiotic relationship which should be in place.

Reaching the conclusion that a young person is dyslexic is not something that should happen through a one-off test. It should be an ongoing process and a response to observing a child or young person’s difficulties.

Clearly how we assess is dependent on knowing what it is that we are assessing, and for that reason we need to start with a definition of dyslexia. In Scotland it is recommended to use the 2009 working definition that was developed by the Scottish Government in conjunction with the Parliamentary Cross Party Group and Dyslexia Scotland and which has been agreed by the Association of Scottish Principal Educational Psychologists (ASPEP).

The process of assessment should begin with observation – which is something that every teacher does. When a child is observed to be experiencing difficulties for example it is considered that they are not making appropriate progress in literacy, then that will be the start of the process.

Specific approaches and interventions can be put in place with the intention of ensuring the child makes good progress and makes up for any gaps that have become apparent

Identification and timescales

Scottish legislation provides an entitlement for families and learners themselves over 12 years of age to request an assessment of dyslexia. This process should start within 10 weeks of the written request. However, the specific timescale it should take to carry out a holistic/collaborative identification of dyslexia is not set in legislation or policy. Neither do the family or learner have an entitlement for specific types or names of dyslexia assessments or tests to be used.

The Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit highlights the difficulties which can arise if the assessment/identification process is a long one and places a very high value on effective communication during this time to support and maintain positive relationships with all involved during this process. The holistic and collaborative process of identification which is recommended within the 3 -18 curriculum is undoubtedly a longer experience and process compared to an independent assessment. It should be appreciated that the differences between the two assessment processes and the timescales can cause families a great deal of confusion and frustration. It is therefore important to ensure the process and methods used by the school to gather information for an identification of dyslexia is done so in a timely and efficient way.

The Process of Identification.

Recap

The Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit and Modules 1 and 2 provide information on the identification pathway for dyslexia and literacy difficulties. This section aims to explore this in further detail.

Module 2 section 2.3 explained that everyone has the skills and abilities to recognise early signs of dyslexia in children at all stages, and to take appropriate action in response. Pupil support begins with the class teachers; however this does notmean that class teachers are responsible for the formal identification of dyslexia. It means they play an important role in the initial stages and the continuing monitoring and assessment of learning – as they do for all their pupils.

The Toolkit and the modules highlighted

- The rationale of a dynamic and holistic assessment

- The roles of those involved in the process

- That parents, carers and children over 12 years old have the legal right to request an assessment and this should be started within 6 weeks of the request.

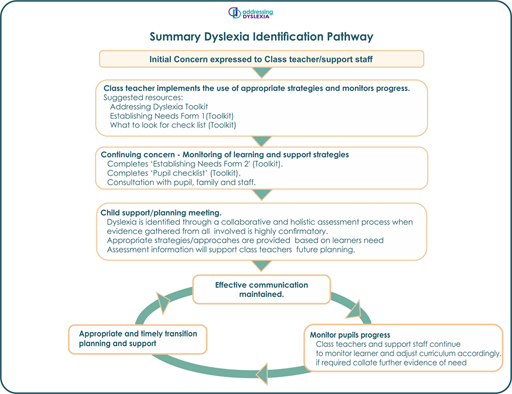

Figure 10 provides an overview of the identification pathway.

You should be familiar with the Scottish working definition of dyslexia. However to help work through this section the following files aim to provide some support and are available on the Toolkit.

Click the ‘link’ to the Scottish Working Definition - http://addressingdyslexia.org/ what-dyslexia

Download a copy of the Scottish Working Definition and Planning Tool

Click the ‘link’ to access an expanded version of the identification pathway - http://addressingdyslexia.org/ assessing-and-monitoring

- Starting the Process

- What to look for

- Other factors

Starting the Process

Modules 1 and 2 have highlighted that the family or class teacher may not be the only people who can highlight concerns that a child or young person may be dyslexic. Irrespective of who raises the concern, it is recommended that the class teachers start the process by considering the learner and looking at the Scottish working definition of dyslexia which provides support for all involved as it highlights the range of characteristics to focus on. These can be used as a framework for identification. When a concern is first highlighted it is helpful to consider the range of reflective questions highlighted. These are applicable for all levels within Curriculum for Excellence and can be adapted to the age and stage of the learner.

A range of templates are available to support this stage of the process and are available on the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit – look at the sections ‘Assessing and Planning’ and also ‘Resources’

Considerations for teaching – (or you may be observing the learner being taught by another teacher)

- Did I present this in a clear manner?

- Did I talk too quickly?

- Did I gain the child’s attention?

- Did I make assumptions about the child’s prior knowledge?

- Developmentally was the child ready for this?

- Did I talk beyond the child’s concentration span?

- Was the child interrupted or distracted by anything or anyone?

If there are ways in which you or the teacher can change the language used in class and/or teaching to support the child’s learning, then this is probably the first course of action.

The classroom

- When I am talking, are children seated so that they can all see me without having to turn their heads?

- Is the classroom welcoming?

- Are children aware of where their individual coat pegs are? Can they recognise their own peg easily?

- Is there an appropriate place to change shoes and store belongings tidily?

- Can I make the walls more dyslexia friendly? (Too much visual material can be confusing if child doesn’t understand what it is about.)

- Do I consider the social mix of children within groups so that children can feel supported without feeling their abilities are underestimated?

- Do I encourage a range of metacognitive styles?

- Are there appropriate consistent daily routines so that the child knows what to expect?

- Is the visual stimulation in the classroom at the appropriate level? Visual impact is improved too when there is clear organisation within the classroom, including the classroom walls.

- Children with difficulties are often easily disorientated so require consideration to be given to aspects of seating. It is important that they are able to receive attention without having to turn around to see the board or the teacher.

The curriculum

- Can the learner access the curriculum?

- Is the curriculum appropriately differentiated?

- Do the parents have opportunities to understand what is being taught and how that can help at home?

- Consider all transition information when appropriate.

- Discuss the child's learning with parents sensitively. They will know their child but where there is no family history of dyslexia this may not have been considered, and in the early years, it is not appropriate to label or to be emphatic about the child's learning as children all develop at different paces, and some children are just developmentally a little slower than others. However, it is important to try to ensure that the child is learning effectively whatever level they are at.

- Close collaboration with family and/or carers should be continuous and central to the ongoing support through the Staged Process which may or may not lead to fuller assessment if required. Your reports back to family, and colleagues, should not cause concern, but should be supportive and helpful pointing the way to how working together can benefit the child.

- Working with the child and his/her parents, discuss and complete the "What to look for" checklist.

Note: Your local authority may already have appropriate paperwork for noting concerns, so you should check first.

- Reflect on the ‘Other factors to consider’ and keep these in mind as you build your understanding of this child.

- Consider if more detailed classroom observation is appropriate and think about your own teaching approaches.

- Consider the child's previous medical and developmental history.

Early level

In the early years, even though there may be a known family history of dyslexia, the procedure is not one of labelling but of observing the children, noting any areas of difference or difficulty and adapting learning and teaching approaches where appropriate. Children all develop at different rates so it is important not to jump to conclusions too quickly. Even terms such as ‘dyslexic tendencies’ or 'dyslexia signs' can be potentially confusing for pupils and parents and should therefore be avoided. It is important to be precise and identify areas of need so support can be targeted. Dyslexia often overlaps with other difficulties and there are many factors that may influence our observations. For example, children for whom English is an additional language may appear to be developing language in a different way from native English speakers.

The recommended procedures relate to dyslexia, but it is likely that observations will be to look at all the strengths and weaknesses that children will be exhibiting. These will be conducted within the context of Curriculum for Excellence to ensure that the child is not put under stress, and at pre-school, will be in the context of play situations. What is most important at this stage is not assessment but the interventions and experiences that are put in place following observations. Parents should be aware that their child’s progress is being continuously monitored so that any appropriate steps are taken to alleviate difficulties at the earliest possible stage to avoid later problems.

Even when children start to learn to read, it is wise to exercise caution with regard to labelling children as dyslexic. Children will only just be beginning to develop their skills in reading and writing at the early stage. Parental support at home is important but shouldn’t lead to stressful situations, so formal “homework” should be avoided and appropriate support through play contexts should be discussed. For this reason there should be regular liaison with parents to agree what will be most appropriate and children’s progress should continue to be monitored.

A simple coding system for recording observations (e.g. the traffic lights system) often works well as a good way of recording and accessing information in the early years. Busy staff require a straightforward means of sharing information that can easily be updated as there are changes in the child's development. For this purpose, use whatever has been agreed and works well in your establishment. Any longer term or more serious concerns about the child's development and progress do require to be recorded in more detail in the Staged Process paperwork. It is also important to tie in your documentation on observations with other establishments at key transition stages.

If the child does not exhibit any of the indicators noted, then continue to observe in the normal way.

If however there are some signs of difficulties in these areas then the Staged Intervention process should be followed.

First and Second levels

It would be hoped that any difficulties with literacy that the child is having will have been recognised at the Early level, and teaching approaches and support will be in place already with focused intervention targeted to meet the child’s needs. However if the child has not been previously recognised as having difficulties, then it is important to take steps as early as possible so that motivation and self-esteem do not suffer.

It is recognised that dyslexia often overlaps with other difficulties and it is important to be alert to a wide range of factors. If this is felt to be the case then discussion with parents will help establish if there has been any previous involvement of the community paediatrician, speech and language therapist, occupational therapist, physiotherapist or other professional. For children who are learning English as an additional language too, this must be taken into account. Observations will be made within the routine of the classroom using the existing Curriculum for Excellence to ensure that the child is not put under undue stress. Even though we may be unsure at this stage whether or not the child is dyslexic, appropriate interventions and experiences should be put in place following observations. Parents should be aware that their child’s progress is being continuously monitored so that any appropriate support that they can give at home ties in with what is happening in school.

Formal "homework" should be issued with much care as this is often a stressful time for both child and parent when the child is tired and reluctant to repeat previous failures from earlier in the day. Regular liaison with parents will enable agreement on what is reasonable and what will be most appropriate to maintain progress.

A pupil who may merit further consideration is one who typically manifests some combination of these characteristics:

- Unexpectedly poor spelling, poor decoding and hesitant reading, and/ or poor handwriting/ organisation of writing on page

- Disorganisation – untidy desk, school bag and books spread over an area, slow to get started work, last or almost last getting changed for Physical Education etc, loses things – pencil, rubber etc

- A pattern of strengths and weaknesses across the curriculum - for example, Language work may often be an area of relative weakness with oral work much superior to written work and reading

- Behaviours that might seem aimed at deflecting attention from the task in hand - sore tummy, needing the toilet, clowning around, pencil sharpening etc.

Third and Fourth and Senior levels

At the these levels, most learners with dyslexia will already have been identified as having specific difficulties and will have been noted as being on the Staged Process of Assessment and Intervention. For those who already have a differentiated curriculum or specific accommodations in place to meet their needs, it is important to ensure that information is kept up-to-date and revisions made to the support, teaching and accommodations, as required. Collaborative work with ASN/SfL/Guidance/Pupil Support staff and management (as appropriate) will help ensure that the needs of the learners are met.

However for some, as school work becomes more demanding and the amount of reading and writing increases significantly, this will be the time when they recognise that they are not coping as well as they might with appropriate help. It is important therefore to consider the child and look at the Scottish working definition of dyslexia and the associated characteristics. As you are aware dyslexia often coexists alongside other associated difficulties, it is important to be alert for a wide range of factors. A pupil who may merit further consideration is one who typically manifests some combination of these characteristics:

- Unexpectedly poor spelling, hesitant reading, and/or poor script/page layout

- Disorganisation - chaotic notes, homework and coursework late, is frequently late for classes, takes ages to change after PE, loses schoolbag, etc

- Distinctive patterns of strengths and weaknesses across the curriculum - for example, English may often be an area of relative weakness; and teachers of ‘essay-based’ subjects (e.g. History, RMPS, etc) may notice that exam scores don’t match with the level of competence displayed in discussion or in orally-based learning. This may not be immediately obvious to individual subject teachers who are not observing the child in all subjects, but may be worth discussing with colleagues

- A learner clearly copes with the subject demands in class but completion of longer written assignments is disappointing and performance in timed tests is poorer than expected

- Behaviours that might seem aimed at deflecting attention away from academic success - anything from frequent minor ailments to playing the class clown

What to look for

A range of templates are available to support this stage of the process and are available on the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit – look at the sections ‘Assessing and Planning’ and also ‘Resources’

Other factors to Consider

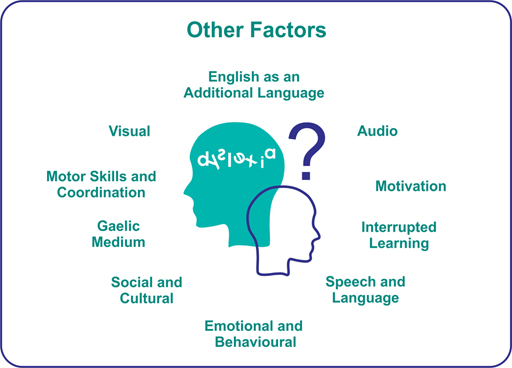

Module 2 highlighted that when starting the process of identification of dyslexia, particularly if the concern has arisen due to difficulties in the acquisition of literacy and language skills practitioners need to explore, indeed rule out other possible factors which can impact on the development of literacy skills, some of which are highlighted in figure 11. Conversely as with the characteristics used in the Scottish working definition, these factors may be areas of strength.

Audio

Audio Processing Difficulties (APD) are one of the associated characteristics for dyslexia and may manifest as difficulties in processing and distinguishing sounds/ syllables/words and identifying where they heard them in words/sentences may have an auditory processing difficulty.

(APD) can affect people in many different ways. A child with APD may appear to have a hearing impairment, but this isn't usually the case and testing often shows their hearing is normal. It can affect their ability to:

- understand speech – particularly if there's background noise, more than one person speaking, the person is speaking quickly, or the sound quality is poor

- distinguish similar sounds from one another – such as "shoulder versus soldier" or "cold versus called"

- concentrate when there's background noise – this can lead to difficulty understanding and remembering instructions, as well as difficulty speaking clearly and problems with reading and spelling

- enjoy music

If APD is suspected then it is important the family consult with a medical practitioner and this should be discussed sensitively with the family.

Motivational factors

Linking very much with health and wellbeing there may be reasons why the learner does not appear to be motivated to engage in particular aspects, or most aspects of learning.

- Health and wellbeing aspects

- Disengagement - Not wishing to appear to be working at a lower level than their peers

- The reading/topic subject matter does not enthuse the learner to persevere – they may have no interest in the topic of the reading book/scheme

This is a very important area because tapping into the learner’s motivational interests and strengths can provide a way forward in developing appropriate support and strategies.

Interrupted learning

Children who miss a significant amount of schooling at important stages for learning, or who have limited language experience may exhibit signs of literacy difficulties due to having lost out on the teaching and learning of specific parts of phonics that are essential for reading, spelling and writing. If this has not been compensated for at home or in later schooling, then this may explain why their difficulties are growing. Lack of ability to read often means that the child does not try to read, and therefore loses out on new learning. This then sets off a downward spiral of poor school experiences that is self-perpetuating.

It will be important to ensure that such factors are taken into account in the observation and assessment process at this stage, and steps taken to ensure that any gaps are identified. This means young people can receive appropriate teaching to make up for the missed areas, or when this is unlikely to be possible to circumvent by providing for example, a text reader that the child can use with earphones on the computer to access whatever text the rest of the class is working on. Specific focused teaching of phonics is not easily embarked on at this stage, so circumvention strategies that will help the child avoid the failure s/he has become used to, are vital. Information should have been recorded regarding gaps in learning on SEEMiS and or recording methods in your school/local authority and you should access this and put in place any necessary steps so that detailed assessment can take place.

Speech and Language

Although not all young children with dyslexia have early speech and language difficulties, there is evidence that many do. Early speech and language difficulties may be indicative of later difficulties in acquiring literacy. Also dyslexia can co-occur with ongoing speech and language problems. Furthermore ongoing language problems may also be associated with reading comprehension difficulties. Practitioners need to be aware of these associations and if there are problems with a child’s speech and language, then early intervention is likely to produce the best outcome for the child.

Children may have difficulty in sounding out words and have problems with phonological awareness. A case history of early development and information about early/previous/ongoing input from Speech and Language Therapy is helpful.

Children with dyslexia may be able to say a word but cannot break it down into syllables and/or sounds. They may have difficulty working out the constituent sounds in a word e.g. they are unable to blend d-o-g to make ‘dog’. For others, their auditory awareness of sounds is impaired, so they are unable to say where in the word a sound comes e.g. they are not aware that the /b/ sound in ‘boy’ comes at the start. For those children training in auditory discrimination is vital if they are to be able to learn phonics successfully.

If there are concerns over elements of speech and language development, then referral to a speech and language therapist is advised for advice and appropriate management. Speech and Language Therapy involvement may be at Stage 1 where there are early speech, language or communication difficulties. Advice regarding Speech and Language Therapy in association with ongoing concerns regarding literacy development may be sought at Stage 2 or 3 of the Staged Intervention process, depending on supports available locally. Referrals can come from a range of different sources, but must always be done with the parent’s consent.

Emotional and Behavioural Factors

There are many factors that will influence how a child adapts and responds to the learning environment. Feelings of failure will affect the child’s learning, so it is important to consider possible reasons for any problems in the behaviour field and try to find ways for the child to succeed. Close liaison with parents will be required to establish if there are factors that we need to be aware of, and take account of in teaching – e.g., in what circumstances does the child respond well? – e.g. Does s/he like to be given responsibility? Who are his/her role models?

When considering dyslexia assessment, it is important to ask yourself why the child is behaving in the way they are as this is not always obvious, and sometimes may be due to the frustrations the child feels when not learning as they feel they should, and seeing a gap between what they can do and what others can achieve. This will be particularly frustrating if that gap is also growing! It is important not to rule out dyslexia because of seemingly “bad behaviour” but to consider learning in a variety of contexts. If the child learns well at some times and not at others, or in some subject areas and not in literacy, and there is no other obvious reason for this, then consider the possibility of dyslexia.

It is important also to work with families on achieving success in some aspects of learning so that children see the rewards for their efforts as well as achievement. Parents can generally give information on how the child is behaving at home, and this may help you decide on the most appropriate strategies to employ to tackle the difficulties. More detail on the types of behaviours that may be observed are considered under the three headings of:

Disappearing Strategies

Children who have a quiet disposition may adopt the strategy of becoming a ‘Disappearing Child’ in the classroom, by being exceptionally quiet and not drawing attention to themselves at all. They avoid eye contact with the teacher and do not put up their hands to ask or answer questions. Many will perfect a performance that makes it seem as if they are engaging in a task appropriately. They will appear to be writing or reading even though they may have a poor grasp of what the task entails or may not have the skills to accomplish the task. In a busy classroom such children may be difficult to identify for a considerable time which means that they may be lagging far behind peers once they are identified.

In some cases a child will develop a strategy that means they are physically not in the classroom when a particular task occurs, most often reading aloud, which dyslexic children find the most frightening aspect of the classroom. This strategy may take the form of being particularly helpful, so the child may volunteer to take the register to the office or to take messages around the school to other teachers. They will perhaps take rather longer than is necessary to complete such tasks in the hope that the activity that they are trying to avoid will be finished by the time they return. Some children use the pretext of frequent and extended trips to the toilet to achieve the same aim. Teachers should be alert to the timing of these activities. Is there a pattern for example in a child’s behaviour that suggests s/he is concerned about a particular task? At the extreme of the continuum of ‘disappearing’ strategies a child may use illness as a mechanism for avoidance so a pattern of absence related to the timetable may alert either teachers or parents to the child’s underlying difficulty.

Distracting Strategies

For dyslexic children who have good verbal skills the preferred strategy is often that of becoming ‘The Class Clown’ – the child who is always ready with a quip or a joke. On the face of it this behaviour is not likely to endear the child to a teacher but it is likely to result in a high level of peer approval and for a child who feels that he is unable to do what the teacher requires, being popular with peers may seem a worthwhile alternative. This strategy also distracts everyone from the task that the child may fear and is an attempt to avoid being seen to fail by the peer group.

If a dyslexic child is skilled at sport then a focus on that activity may also serve to distract teachers from the child’s difficulties with classroom tasks. Such children often maintain high self-esteem and peer group approval despite having difficulties with text based tasks so there is a possibility that engagement in the sporting activity may lead to difficulties in other areas being overlooked.

Disruptive Strategies

If a child does not have the verbal confidence to become the ‘Class Clown’, or the sporting prowess to aim for ‘Team Captain’ status, then being a ‘Disruptive Child’ may seem a reasonable alternative. Again, as adults we can see how misplaced a strategy this is, but children do not have such a long-term perspective and focus mostly on resolving their immediate difficulties. If the dilemma is how to avoid failing at a particular task, especially in front of friends, then standing outside the door of the classroom as a result of obnoxious behaviour is actually a reasonable solution to the immediate problem. Again, children who adopt such behaviour may well be popular with their peers as watching someone else get into trouble is entertaining but presents no personal risk to members of the ‘audience’.

At the extreme of the continuum of disruptive strategies are the children whose behaviour leads to them being excluded or those who play truant in order to avoid the stress of facing tasks in the classroom that they cannot complete. This of course means that they have also, quite literally, ‘disappeared’. Such extreme strategies tend to occur if some of the other strategies have not elicited the recognition and support that the child needs. By this time the child is likely to have developed ‘learned helplessness’ which is a state in which an inability to undertake particular activities undermines confidence in all tasks, even those that could be accomplished successfully. Such children, though rare, are at this stage ‘lost’ to education as they feel no sense of engagement or ‘belonging’ in a context that has failed to meet their needs.

Children tend to be pragmatic creatures. In reality the child's day to day life in the classroom would be easier if s/he simply undertook the tasks presented so we must conclude that if a child could complete text related tasks, s/he would - simply because it is easier to do so. If a child persists in not completing tasks successfully in the classroom then we should assume that there is likely to be an underlying reason for such behaviour. One possible explanation is that the child is dyslexic and therefore needs additional support in order to develop the text related skills required.

By now, the young person will be only too aware that their learning is not as they would like it to be, and it might be expected that dyslexia will have been discussed. If however, the child has not been formally assessed then it is best to delay no longer as the assessment may help the child’s understanding of his/her difficulties, and hopefully behaviour will improve as a result. It is not unusual for behaviour problems at this stage to be considered as the problem rather than embarking on the pathway to full assessment. Assessment however is important for the young person and his/her parents. This will give a reason for the young person’s problems and also a focus for discussing what can be done to improve both the behaviour and the learning.

Motor skills/co-ordination and organisation

Not all children with dyslexia will have obvious difficulties with motor skills, but even slight lack of co-ordination may influence the child’s ability to cope well with handwriting. When motor skills are affected, this often affects self-esteem as the child has difficulty with sports and physical games. Spatial awareness can be a problem resulting in the child being unaware of where on a page to start for writing or reading until this skill has been overlearned.

Organisational skills are often weak in children with dyslexia. This may or may not be related to sequencing abilities, but these also are often affected, meaning that the children have difficulty in recognising order in days of the week, months etc. If the children are disorganised, and/or untidy, then it is unlikely that they will endear themselves to teachers or their peers. However strategies for organisation and sequencing can be learned and the sooner the better for the sake of the child’s self-esteem and confidence.

If there are concerns over elements of physical co-ordination or motor skills development, then referral to an occupational therapist is advised for advice and possible exercises. Referrals can come from a range of different sources, but must always be done with the parent’s consent.

Social and Cultural factors

- Are there social factors that might help explain the child’s difficulty with literacy development?

- Do you know what the child’s experience is of books in the home?

- Does he or she have the opportunity and/or encouragement to do schoolwork at home at all?

- Is the family supportive of the learner’s schooling, or uninterested/ antagonistic?

Sometimes illiteracy that derives from environmental and social factors will mimic dyslexia: poor literacy, impatience with written learning, poor attention, chaotic organisation, attention seeking, etc.

It may make no real difference to the support you provide at school as a learner with literacy needs will require support whatever the cause of these needs’ - whether the causes are intrinsic or extrinsic - within the learner or deriving from the learner’s environment. But it will be useful to be as clear as possible in your own mind what the balance of factors might be.

Visual problems

Poor readers may have motor and/or perceptual problems with vision, and improving vision can have a very positive effect on accuracy, fluency and understanding of text. Though visual problems are not likely to cause dyslexia, if they are present they will certainly aggravate pre-existing difficulties. Examples of the types of problems that may be present are:

Visual Stress/Meares-Irlen Syndrome

- poor vergence control

- scanning/tracking problems and poor binocular vision

Symptoms of visual problems may include:

- eye strain under fluorescent or bright lights glare

- same word may seem different or words may seem to move

- headaches when reading, watching TV or computer monitor

- patching one eye when reading

- difficulty tracking along line of print causing hesitant and slow reading

If visual problems, such as those above, are suspected, treatment should be sought from a qualified professional orthoptist. There are clinics at most main hospitals and referral can be made through the student’s GP, educational psychologist or the community paediatrician. Treatment may involve eye exercises and/or the use of colour – either tinted spectacles or the use of a coloured overlay.

Further information on visual issues is available on 2 Dyslexia Scotland leaflets

- ‘Dyslexia and visual issues’

- ‘Visual Issues - Frequently Asked Questions’

Which can be found at https://www.dyslexiascotland.org.uk/ our-leaflets

English as an Additional Language

For children who speak languages other than English at home, the assessment process will require very careful consideration, to accommodate the child’s first language as well as English, and this may require assistance from a professional who shares the same language as the child.

It must be remembered that the phonology of the child’s first language is likely to be different from English, and scripts too may be different. As an example, Polish children who have wholly developed literacy skills will have experience of decoding in alphabetic script but in the case of children exposed to logographic scripts, the relationship between sounds and symbols will be markedly different. Even although children may not have learned to read in their first language they will have been exposed to environmental print. The issue for teachers is to consider whether the children’s difficulties with language extend beyond them having English as another language.

’See ‘other factors to consider’ to access further information and resources to support English as an additional Language and dyslexia

Activity 11- Other factors to consider

In your Reflective Log complete the table inserting relevant questions to consider when evaluating and exploring the possible impact of other factors which can impact on the learner and the process of identifying dyslexia.

Once complete consider how you could engage the learner and their family with these questions.

Click ‘reveal’ to see some suggested questions

Discussion

| Factor | Questions | Further questions |

| Audio | Has the child had their hearing assessed? | Is there a history of hearing problems for the child or within their family? |

| Motivational | Does the learner appear to be disengaged | Is the curriculum accessible and appropriately differentiated? |

| Interrupted Learning | Have there been periods of interrupted learning?

| Were there high incidences of absences in the early years of primary school? Is there likely to be further interrupted learning e.g. travelling children, children of parents who are in the Armed Services? |

| Speech and Language | Has there been a history of speech and language delay/Development? Intervention? | What was the impact of any intervention? Is input ongoing? |

| Emotional and Behavioural | Has there been a change at home or out with school? | Have you identified any patterns or triggers to the pupil’s behaviours? |

| Social and Cultural | What is the family’s experience of education? | Do the family engage with education services? |

Motivational factors

| Do they have an interest in the topics? | Has there been engagement with the learner to explore areas they find interesting and incorporate this into the activities? |

| Gaelic Medium | Is Gaelic spoken at home or only in the school setting? | Did they hit their developmental milestones around literacy acquisition? |

| Motor skills/coordination and organisation | Does the child hold a pencil correctly? | Does the child have difficulty forming letters? |

| Does the child appear clumsy/have poor coordination? | Did the child learn to ride a bike within the typical age range? | |

| Visual | Has the child had their eyesight checked recently? | Is the child showing symptoms of or been assessed for visual stress? |

| English as an Additional Language | What languages are spoken at home? (It is more beneficial for a child to develop English if they are fluent in a first language spoken at home) | Is the child’s literacy progressing in their first language? |

Please note the list is not exhaustive and you will be able to develop your own questions which are relevant for the individual children and young people you are working with.

Access ‘The identification Pathway for Dyslexia’ which has been expanded to include additional supports and suggestions

2.2 Appropriate supports

A positive and inclusive school ethos and understanding from staff contributes significantly to providing appropriate support for learners with dyslexia and their families – indeed the same will be for all learners. Due to the individuality of all learners it would not be appropriate to recommend only a few resources from the many which are available. We do not make any set recommendations, but leave teachers and others to evaluate these resources for themselves and establish the most appropriate materials for the individual needs of learners as there is no ‘one size fits all’.

The Resources section within the Toolkit has a range of free resources.

http://addressingdyslexia.org/more-resources

- Auditory and processing skills

- Comprehension

- Coordination

- Literacy

- Literacy – Pre Phonics

- Literacy – Phonological Awareness and Phonics

- Literacy – Reading/writing/spelling

- Memory

- Numeracy and Math

- Visual processing

Dyslexia Scotland has a range of resources available on their website. Some are free to download and some can be loaned or are available to members.

Curriculum Areas

Dyslexia can impact on all eight curriculum areas within Curriculum for Excellence in different ways depending on the individual.

It is important for class teachers to be aware of strategies which may help the curriculum area or interdisciplinary areas they are teaching.

Module 1 and 2 highlighted 2 sets of books below which will support staff across the curriculum

- Supporting Pupils with Dyslexia at Primary School (2011):A series of 8 booklets that were provided to every primary school in Scotland contains information and advice about dyslexia from the early stages to transition to secondary school, and also contains information on support for learning departments, school management teams, as well as, about good practice when working with parents. These booklets can be downloaded by Dyslexia Scotland members from the Dyslexia Scotland website.

- Supporting Pupils with Dyslexia in the Secondary Curriculum (2013):A series of 20 booklets that were provided to every secondary school in Scotland and aim to provide subject teachers and support staff with advice and strategies to support learners with dyslexia. The booklets can be downloaded from the Dyslexia Scotland website.

Curriculum Accessibility

Differentiation

Activity 24, Section 2.2 in Module 2 highlights a range of different approaches to consider when planning effective and meaningful differentiation. Figure 12 provides a reminder. You may wish to revisit this section of module 2.

Activity 12 - Curriculum Accessibility - Differentiation

Reflective questions for professional dialogue with colleagues

The following questions can be used when engaging in professional dialogue during professional learning opportunities and discussions with colleagues. The outcomes from these discussions can support planning for professional learning opportunities and improvement plans.

You can collate the responses in your Reflective Log.

Download a discussion sheet if required.

‘Download’ Differentiation descriptions of the areas to share with your colleagues if required.

- What areas are being used in your school community to support differentiation?

| Area of differentiation | Commonly used in my school | Additional approaches | Ideas raised which have not been used |

| Task | |||

| Grouping | |||

| Resources /Support | |||

| Pace | |||

| Outcome | |||

| Dialogue and support | |||

| Assessment |

- Are there any areas of differentiation which your school are not using which you could support?

- Has any additional good practice been highlighted through our discussions?

2.3 Planning

If a child doesn’t progress as expected, then planning needs to be done accordingly. This may involve seeking help internally from someone with more specialised knowledge, additional experience or training in dealing with literacy difficulties who knows what to recommend.

The support advised may involve some small group work, in some cases (not all) one-to-one teaching, use of ICT, or it might involve specific support strategies like establishing the learner’s understanding of pre phonics, supporting their working memory or paired reading. Usually a combination of approaches is best.

Class teachers continue to monitor progress and if this is NOT satisfactory, then further help will be required from a more specialised professional. This could result in the child taking up a highly structured multisensory programme of teaching. If so, then it has to be ensured that the child does not lose out on other areas of the curriculum.

At all stages, communication with parents and carers is very important to ensure everyone is working together with the child and takes the child’s views into account. This is very much in line with the procedures for ‘Getting it right for every child approach’.

If you have identified a difficulty on the dyslexia continuum, you will require to plan, implement and monitor learning and teaching arrangements that address and make accommodations for the learner's difficulties, including appropriate assessment arrangements.

Local authorities vary in their terminology used to describe planning documents

| Stages/levels | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Examples of plans | Class planning Personal learning plan (PLP) | Individual Education Plan (IEP) | Coordinated Support Plan (CSP) Childs Plan |

Modules 1 and 2 introduced you to the reading and writing circles and the respective planning tools. This module has incorporated the Working Definition of Dyslexia Planning Tool. These resources can support the planning highlighted above.

Personal Learning Plan (PLP)

All children and young people should be involved in personal learning planning (PLP). PLP sets out aims and goals for individuals to achieve that relate to their own circumstances. They must be manageable, realistic and reflect the strengths of the child or young person as well as their development needs.

Monitoring their progress in achieving these aims and goals will determine whether additional support is working. For most children, including many who are dyslexic, a PLP will be enough to arrange and monitor their learning development. The 2017 Code of Practice says that children with additional support needs should be involved in their personal learning planning. It also says that, for many, this will be enough to meet their needs.

Individualised Educational Programme (IEP)

If a PLP does not enable sufficient planning, a child or young person’s PLP can be supported by an individualised educational programme (IEP). An IEP is a non-statutory document used to plan specific aspects of education for learners who need some or their entire curriculum to be individualised. This means that their needs will have been assessed, usually as part of a staged intervention process. It also means that it has been agreed that these needs cannot be met by their teacher or early year’s practitioner through standard adaptations to learning experiences or personalisation. Not all learners with dyslexia will require an IEP as often significant adaptations do not have to be made to meet their needs. IEPs are usually provided when the curriculum planning is required to be ‘significantly’ different from the class curriculum. Involvement with group work or extraction for a number of sessions a week does not normally meet the criteria for an IEP.

An IEP will probably contain some specific, short-term learning targets relating to wellbeing, literacy and or numeracy and will set out how those targets will be reached. It may also contain longer-term targets or aims. IEP targets should be SMART:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Relevant

- Timely

If an IEP is considered appropriate, the child and the parents will require to be involved in drawing up the content, so an initial meeting will be scheduled to discuss what and who will be involved, and the length of time between IEP meetings. Headteachers or the appropriate member of the senior management team should ensure the involvement of all relevant stakeholders in the IEP process. If however, a group plan will be more appropriate, then discussion with parents should still take place to report on the child’s difficulties and the steps that are being taken to meet the child’s needs in the classroom.

On its own, an IEP is not a complete curriculum planner for the learner who has one. Rather, it is for planning those aspects of the curriculum which need to be individualised for them.

IEPs should be monitored regularly and reviewed and updated at least once every term with the child/young person and their parents/carer.

Co ordinated Support Plan (CSP) – Targeted Support

A CSP is a detailed plan of how multi agency support for a child will be provided. It is a legal document and aims to ensure that all the professionals, the child/young person and the parents/carers work together and are fully involved in the support. Dyslexia on its own as an additional support need would not commonly trigger the opening of a CSP.

Child Plan – Targeted Support

In line with the 2014 Children and Young People Act and ‘Getting it right for every child’ (GIRFEC) approach, many children will now have a Child’s Plan. Child’s Plans are created if a child or young person needs some extra support to meet their wellbeing needs such as access to mental health services or respite care, or help from a range of different agencies. The Child’s Plan will contain information about:

- Why a child or young person needs support

- The type of support they will need

- How long they will need support and who should provide it.

All professionals working with the child would use the plan, which may include an IEP or a CSP.

Planning at Third, Fourth and Senior levels will also be about career choice, and the young person with dyslexia may find this more difficult than others due to any remaining literacy difficulties. However most colleges and universities now have dyslexia advisors and young people should feel confident to find out how the college or university will be able to meet their needs. It is vital that the young person has a copy of their learning profile and understands why they have received any additional support and assessment arrangements. It is actually important that they understand why they are receiving assessment arrangements and how to maximise the use of them. For example extra time is not provided only to write more text, it is to be used to support the learner to plan, scaffold or to proof read their answers and work as well. At this point, school personnel may require to consider if an updated assessment will be required before entry to college or university. It is therefore important to liaise with appropriate staff in the college or university of the student's choice to ensure that updated assessment is carried out if this is going to be necessary - for example, to apply for the Disabled Students Allowance.

If the young person decides to go straight into the world of work, the learner profile provided by school should provide them and employers with information on their strengths, areas of difficulties and strategies which were helpful in enabling the individual to participate in activities and provide a level playing field. Arrangements for work experience if these are handled sensitively might help alleviate any fears the young person has about how they will cope.

Recommendation 5 of the Making Sense review said that there should be improvements made to the quality and use of data regarding the number of children and young people identified as having dyslexia.

‘The availability and use of reliable information on children and young people’s needs, development and achievement should be improved’.

Appropriate early identification planning and monitoring will enable schools and local authorities to ensure the information entered on SEEMiS is robust and up-to-date. This information is collated annually for the schools census and published by the Scottish Government.

2.4 Reporting

All learning and teaching approaches and strategies that have been used should be recorded in the Staged Process paperwork which should then be passed on between classes and nurseries/schools. Parents should be aware of any information that is held in paper form, should be fully aware of what is happening and should collaborate in deciding the best approaches and strategies to be adopted. This needs to be dealt with in a sensitive way to avoid any possible over-reaction and distress to either parents or child.

Reporting to parents/carers may be done orally at the initial stages though clear records should be maintained of the child's progress and consideration should be given to the necessary record keeping within the Staged Process of Assessment and Intervention. All records of this nature should be communicated between classes and schools.

All those involved in the identification and assessment process should be clear about their use of language and avoid terms such as ‘tendencies’ or 'signs' which can be potentially confusing for pupils and parents. The Scottish Government definition should allow for a pupil either being dyslexic or not, but to what extent will vary along the continuum.

All reporting has to be done sensitively as it is important not to convey either stress to the child or worry to parents. It is important too that parents are treated as partners and there is collaboration on what is done in school and what is done to support the school work at home even though home is not usually the place for any formal teaching unless the child is being home educated. A tiring day in the classroom needs to be followed by something much more light hearted. Reading to or with the child rather than formally hearing reading for example can take stress away from both the child and his/her parents. Initial observations of difficulties should be dealt with as concerns and parental support and help at home should be elicited through discussion of what the school is doing.

Assessing for dyslexic difficulties is a collaborative process throughout - parents/ carers, colleagues and the child concerned should share as fully as possible at every stage of the process. Reporting ranges from:

- Maintaining regular contact with parents over any concerns at Assessment and Intervention Stage 1 through to:

- More continuous and detailed sharing of insights at Assessment and Intervention Stage 2, and

- A full assessment and report at Assessment and Intervention Stage 3, which collates and interprets all the available data and insights into an analysis/ summary/ report that should be helpful and informative to all those involved in helping the child to cope with school and the literacy demands of life.

At the initial stages of the identification pathway, where dyslexic difficulties are not presenting a significant barrier to learning, or where investigation is still in the early stages, there are a number of ways in which understandings may be shared - for example:

- At parents' meetings

- Through collaboration with colleagues

- Through routine pupil reports

- By means of pupil profiles; and

- Any other routine means of dissemination that are used in school.

The specific means will vary from school to school - but it is vital that any assessment information is shared regularly and transparently throughout the process.

The young person should be at the centre of every stage and aspect of the process of assessment and reporting and their feelings given consideration.

A formal report focusing primarily upon how dyslexia is causing barriers to learning may be appropriate and helpful, particularly if the child is moving away or changing schools. The name of this report may vary for example it may be referred to as a formal report or a Learner Profile.

Where there are other agencies involved with the young person the necessary information may well be incorporated in the reporting arrangements of another professional e.g. the school’s educational psychologist. If this is the case, then a stand-alone report may not be needed - but it may still be helpful, as it will represent how this learner’s needs uniquely present and are being understood and met within the school, i.e. -the unique context within which this learner is working.

Assessment of Specific learning difficulties (SpLD) among young adults for the purposes of applying for DSA requires a range of tests to investigate the cognitive profile of the students as well as their attainments in literacy and (where appropriate) numeracy. For such reports, tests of cognitive functioning and underlying ability are regarded as essential for full assessment as well as tests of attainment.

At school level this need not always be the case, but the young person or their parents have the right to request such assessment. However when considering requests to SQA, it will need to be demonstrated that the dyslexic difficulties do constitute a barrier to attainment i.e. that there are underlying abilities that will not be reflected in one or another subject unless appropriate arrangements or accommodations are made.

There are some important factors to consider when writing and developing reports.

- All reporting has to be done sensitively as it is important not to convey either stress or worry to parents and pupil

- The report provides an holistic overview of the learner

- Parents and carers must be treated respectfully as partners

- The learner has been involved in the process of developing the report i.e. the process has been carried out with them and not too them

- Support collaboration on what is done in school and what is done to support the school work at home. Ensure any ‘home work’ is engaging and appropriate A copy is provided to the family and learner – this is particularly important if the learner is in secondary school so they have a copy to support them post school.

- Highlight supports in place

- It is written in an accessible way e.g. plain English

- Includes recommendations/next steps

- All learning and teaching approaches and strategies that have been used should be recorded in the Staged Process paperwork/establishing needs form

- The appropriate information is included

Parents and learners (age and stage appropriate) should be:

- Aware of any information that is held in paper form – including assessments

- Fully aware of what is happening

- Included in deciding the best approaches and strategies to be adopted. This needs to be dealt with in a sensitive way to avoid any possible over-reaction and distress to either parents/carers or the pupil. Be aware and sensitive that the concern and distress will be real and may be justified.

The report draws upon the range of information provided by the identification process and includes a range of appropriate support approaches recommended by various professional organisations which have specialist roles in reporting upon specific learning difficulties and dyslexia.

The Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit has a range of templates which can be used for reporting.

2.5 Learner Profile

As highlighted in section 2.4 the Learner Profile is an important document which should be given to the parents and to the learner if they are in secondary school. This is particularly important if post school transition planning is taking place as colleges and universities can ask for this information.

2.6 Standardised assessments

Not all local authorities use standardised assessments in their process of identifying dyslexia. However many find them a useful tool. A standardised assessment to identify additional support needs are tests which requires all test takers to undertake the same task or answer the same questions in the same way. The answers or responses are then scored in a “standard” or consistent manner and compared to a set of data which has been complied by the answers provided by individuals who do not have additional support needs. This makes it possible to compare the relative performance of learners and establish a chronological age comparator. The term "normative assessment" refers to the process of comparing one test-taker to his or her peers.

Activity 13 – Evaluation of standardised assessments

Find out if your school or local authority uses standardised assessments in the identification process of dyslexia and literacy difficulties. If your school/authority does not use them find out about some commonly used assessments and compare your process with one which includes standardised assessments.

In your Reflective Log consider and evaluate the type and use of Standardised assessments in use e.g.

- Are they screeners or assessments?

- Are they appropriate – e.g. date of publication, age range individual tests target , areas of focus

- The methodology in the way they are administered, is it a learner centred process?

- Interpretation of the assessment – usefulness of data and findings provided – how can this be implemented into practice, how is the information used to support learners and the monitoring process?

- How are standardised assessments used within a collaborative identification process?

2.7 Assessment Arrangements

SQA Assessment Arrangements

The purpose of assessment arrangements is to provide candidates with an equal opportunity to demonstrate their attainment without compromising the integrity of the assessment. Candidates are individuals with a diverse range of needs and it is important that you consider the individual assessment needs of your candidates when considering the most appropriate assessment arrangements.

In line with the Equality Act 2010) the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) will, as far as possible, ensure that barriers to internal and external assessment are avoided in the specifications for qualifications, and will make reasonable adjustments/ assessment arrangements for disabled candidates and/or those identified as having additional support needs. Assessment arrangements are adjustments to the published arrangements and are intended for young people who can achieve the national standards, but cannot do so by the published assessment arrangements – the reason for this might be a physical disability, a sensory impairment, a learning difficulty or a temporary problem at the time of the assessment.

In school settings a ‘formal’ or independently provided identification of need is not required for a learner to be provided with appropriate assessment arrangements. The determining factor is providing evidence that the candidate has been identified as having a particular difficulty and that support in accessing the assessment and demonstrating attainment is needed. The collaborative identification process supports this approach.

Examples of assessment arrangements:

- Adapted question papers

- Assistance in aural assessments

- Extra time may be permitted in any timed assessments

- Extension to deadlines

- Use of ICT or Digital Question Papers

- Numerical Support in Mathematics Assessments

- Practical assistant

- Prompters

- Reader

- Referral of a candidate’s scripts to the principal assessor

- Scribe

- Using sign language in SQA assessments

- Supervised breaks or rest periods in a timed assessment

- Transcription with correction of spelling and punctuation

- Transcription without correction

You must submit requests using the Assessment Arrangements Request (AAR) software for all assessment arrangements required in the external Diet of examinations. In submitting requests for the external examination it is understood that the arrangements requested may also be used in any assessments undertaken internally. Each year, in October, access details and a link to the AAR user guide will be e-mailed to your SQA co-ordinator.

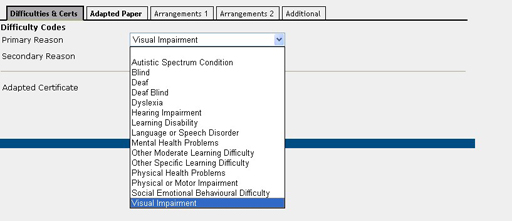

Figure 13 provides a screenshot. This information on different categories of difficulties is collated for internal use within the SQA is should not be interpreted as a requirement to have a formal diagnosis.

For candidates who are disabled, as defined under the provisions of the Equality Act 2010*, assessment arrangements might be the ‘reasonable adjustments’ required to compensate for a substantial disadvantage, but there may be other unique adjustments that need to be made to meet their individual needs.

However, it is important to recognise that some adjustments may not be possible for some qualifications. It is not possible to make an adjustment to the standard of the qualification where to do so would mean that it did not provide a reliable indication of the knowledge, skills and understanding of the candidate. Some candidates, defined as having additional support needs under the Education (Additional Support for Learning) (Scotland) Act 2009, may also need an assessment arrangement to meet their identified physical (including medical or sensory), behavioural, mental health or learning difficulty.

Not all candidates with assessment needs will be disabled and, conversely, not all disabled candidates will necessarily require assessment arrangements to enable them to access an assessment and demonstrate their attainment. In all cases, it is the individual assessment needs of candidates that must be the basis for the provision of an assessment arrangement. This means that SQA centres (schools) have a critical role in ensuring that the process of providing assessment arrangements is fair and operates with integrity.

Candidates for whom assessment arrangements are provided should potentially have the ability to achieve the national standards, but be unable to do so using the published assessment procedures

Important factors to remember:

- The integrity of the qualification must be maintained.

- Assessment arrangements should be tailored to meet a candidate’s individual needs.

- Assessment arrangements should reflect, as far as possible, the candidate’s normal way of learning and producing work.

However, there may be situations where a candidate’s particular way of working in the learning environment is not acceptable in an assessment. For example, a candidate who has a language and communication impairment, and who normally has someone in class supporting them by explaining words and terms, would not be allowed such support in the externally-set examination question paper. For this reason, it is very important that candidates are aware of, and have practice in, working in a way that reflects what is going to be allowed as support in the assessment situation

You can access ‘further information from the SQA’ - ‘Assessment Arrangements Explained: Information for centres’ and ‘Quality Assurance of Assessment Arrangements in Internal and External Assessments: Information for Schools’ which can be found here

https://www.sqa.org.uk/ sqa/ 14976.html

Post 16 support

Building the curriculum 5 A Frame work for assessment highlights; 16+ Learning Choices aims to ensure that all young people have an offer of appropriate post-16 learning along with the necessary support to enable them to move into positive and sustainable destinations. Ensuring appropriate information, advice and guidance along with the necessary support and more choices and more chances for those learners who need them, will be an important part of providing an inclusive approach to learning, teaching and assessment in the senior phase.

Transitions will be covered in the next section but it is extremely important

- To ensure that all appropriate information about the assessment arrangements which have been evidenced and provided for the learner is included in the learner’s profile.

- The learner understands why they have each type of assessment arrangement and how to use it. For example extra time is not provided just so the learner can write more. It is there to support the task preparation and completion e.g.

- scaffolding and planning

- proof reading their answers

- additional processing time

Ensuring that the learner and their family have a copy of the SQA assessment arrangements which were in place at school will:

- Support and inform the post school transition process.

- Reduce the length of time it takes to establish the appropriate support post school

- Reduce the need for the post school establishment to contact the school for information. This can be a very time consuming process and may provide the information sought due to data protection issues if the learner has not given prior consent for their information to be shared.

Transitions

Recap

Module 2 section 2.5 highlighted the important issue of transitions

It important to understand that transitions occur each day, through the year as listed below and not only at the commonly highlighted stages such as P7 – S1 or S4/5/6 to post school.

- Nursery to P1

- Class to class

- Year to year

- P7 – S1

- Broad general education at the end of S3 into the senior phase

- School to Offsite to school

- Post school

Access the Transitions section within the Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit. New resources are being added and a range of short animations are available.

Post School Transitions

Post School Identification and Support

The criteria involved in providing a post school identification of dyslexia is different from the criteria for a young person who is attending school in Scotland. Therefore it is important that the information gathered at school is made available to the young person before leaving.

Post school Independent Assessments are carried out by practitioners who hold specific qualifications which are not required for teachers in Scottish schools. Independent assessors usually charge for this service.

Employers are not obliged to help with the cost of an assessment but often recognise the benefits an assessment can have for the company and their employee. Support in the workplace is available through the Access to Work programme, arranged through the Job Centre.

Students in Further or higher education

Colleges and Universities have a duty under the UK wide Equality Act 2010 to make ‘reasonable adjustments’, to ensure that students with disabilities are not placed at a disadvantage in comparison to non-disabled students.

This is an anticipatory duty which means that education providers should continually review and anticipate the general needs of disabled people, rather than simply waiting until an individual requests a particular adjustment.

Students might also be able to apply for the Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA), through Student Award Agency Scotland (SAAS). An assessment is required to access the grant funding. The assessment has to meet a set of criteria and must be carried out by appropriately qualified practitioners - Educational Psychologists or dyslexia specialists.

An Independent Assessment is not required prior to course entry at college or university, particularly if an appropriate assessment has been carried out in school by a qualified individual. If an assessment has been carried out in school, and updated around the age of 16, then some Universities will accept that as proof of dyslexia without the need for any independent, paying assessment. If an assessment is not in place prior to the start of the course, this can lead to a delay in support and assessment arrangements being in place.

In summary the entitlement to assessment and identification of dyslexia differs between school and post school due to the different systems which have been developed for different settings and age groups. It is advisable to contact the colleague or university in advance to find out what their procedures are.

Ensuring that all pupils who require one have access to their learning profile and record of identification prior to leaving school will as discussed in section 2.5, provide valuable information to the post school setting. However for this to happen the transition planning must:

- Be planned in advance and in accordance with the 2017 Code of Practice

- Contain appropriate and robust information

Difficulties arise once the learner has left school as school cannot pass on to third parties information unless they have permission as this will breach data protection legislation. It can be a very difficult and busy time when term starts at college and universities as staff try to gather information on the student’s support need. Problems arise if the student does not have an appropriately robust learning profile which highlights their:

- Strengths

- Areas of difficulties

- Motivations

- Supports which have been in place – including SQA Assessment Arrangements

The Addressing Dyslexia Toolkit has a range of templates which can be used for reporting and providing learner profiles which include post school profiles

Activity 14

How can you ensure you are capturing learners’ strengths as you are progressing through the identification and support process and developing the learner’s profile?

Evaluate the information your schools /authority uses for developing learner’s profiles

Suggested Reading

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/auditory-processing-disorder/

The Dyslexia Assessment 978-1472945082 2017 Dr Gavin Reid and Dr Jennie Guise

Now go to 3 Enquiry and research