Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 20 February 2026, 7:48 AM

Section 1: What do you need to know to teach early reading?

Introduction

In this section you will:

- reflect on how children learn to read

- think about how effective literacy teachers can support children’s reading.

You will think about your own experiences as a child, and how you can support reading development. The course’s approach to teaching children how to learn to read begins here.

Foundational literacy

Early reading is part of ‘foundational literacy’. We see literacy as being about much more than learning to read and write. Being literate enables someone to be an active participant in the social and economic life of the community in which they live. Literacy is at the heart of human wellbeing.

Throughout this course, we will use the terms ‘foundational literacy’ and ‘literacy’, as well as talking about ‘early reading’. We see early reading as being part of literacy. Some of the activities we will introduce you to support children’s literacy development, whilst others will be specifically about early reading.

In order for children to develop as readers they need a literacy curriculum that motivates and inspires them and one that understands the important role of foundational literacy in learning.

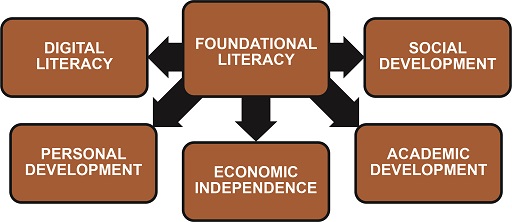

Activity 1.1: The importance of foundational literacy

One of the course writing team was thinking about the importance of foundational literacy and produced the diagram below. For them, reading and writing has a professional role as well supporting social and personal development.

Within your context, why is foundational literacy so important? Think about foundational literacy in your personal life and in your professional contexts. Draw a diagram like this one in your study notebook to capture your ideas.

In your study notebook, find a way of recording your reflections of being a reader and writer. If you wish, share your thoughts with a colleague.

This course is based on these principles of foundational literacy:

- Literacy is meaningful and purposeful.

- Literacy learning rests on a foundation of oral language.

- The many elements of reading and writing are interdependent.

- Literacy learning is a recursive process, requiring the active participation of well-motivated children.

- Teachers need to be readers and writers themselves so they can model for children literate ways of behaving and participating in literate communities.

- Children’s first experiences of literacy learning should be in a language with which they are completely familiar.

- Effective literacy learning depends on the availability and skilled use of appropriate resources, which may include digital technologies as well as attractive reading texts and simple writing materials.

- Reading and writing are complex; teachers need many different strategies to ensure the success of all children.

Something to think about: Reflections on being an adult reader and writer. Re-read the eight principles listed above and choose the one that you think is the most important to you.

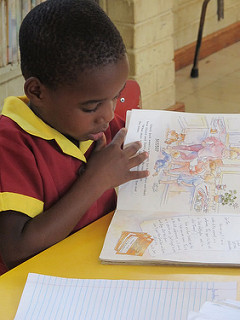

Central to being literate is being able to read fluently with understanding. This course will help you to become a more effective teacher of early literacy by showing you a number of active learning approaches and showing you how to create and access resources that will support children’s early reading.

How do children learn to read?

You are a skilled and confident reader. You are reading this academic study unit, and it is likely that you read every day for work and for enjoyment in books, newspapers, magazines, and of course online. But how did you learn to do all this?

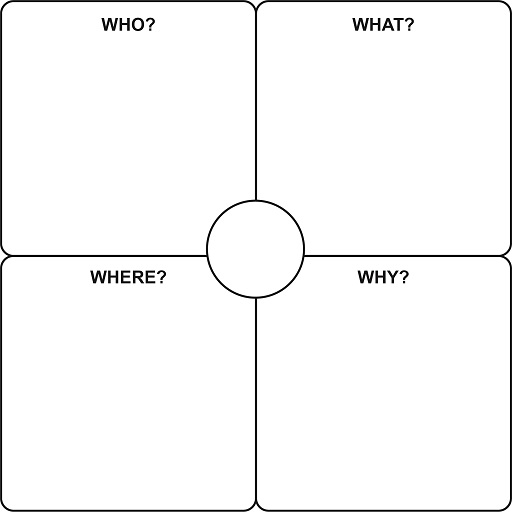

Activity 1.2: Your memories of learning to read

Think for a moment about your own experiences as an early reader when you were a young child.

- Who helped you learn to read?

- What did you read for the first time?

- Where did you read it? Why did you read it? Did you read it more than once? Have you read it since?

Create a chart in your study notebook like the one in Figure 1.3. Write your name in the middle of the chart. Then write your answers to the following questions:

- Was there someone who helped you learn to read?

- What do you remember reading?

- Where did you lear to read – in school, at home or in another place, or a mixture of these?

- Why was learning to read important? What factors do you think made it possible for you to learn to read? Or were there factors that prevented you from learning to read?

Share your memories with a colleague and discuss what were the similarities and differences between your memories of learning to read.

Comment

As you can see, there are many pathways to reading – there is no single way to learn how to do it. There are also many reasons to read, for pleasure, for information and for a range of different purposes. Often, our most important reading experiences happen at home and with family members, before we start school.

Now look at Figure 1.3 from the perspective of the young children who are in your classroom. Instead of your own name in the middle of the chart, add the name of one of the children in your class. As the teacher of early reading, you are the ‘Who’ in this chart, but there may be other people who will also play a significant part in this child learning to read. The ‘Where’ is your school, but home or church may also be an important place in this child’s ‘reading journey’. The ‘Why’ of reading will be individual to each child. Later in this course you will focus on ‘What’ to read when we look at different resources.

School reading can be very different to reading that is done at home and in the community. As a teacher, it is your job to draw on all the resources available to the child to help them to see the value and enjoyment in learning to read, and not just something that they do at school. In this way you will be contributing to their personal development, and wellbeing.

Activity 1.3: Analysing the experiences of others when learning to read

Read the comments in Figure 1.4 that African teachers have shared with us about learning to read. As you read their memories, think about the following questions you have already reflected on:

- who helped them read?

- what they read?

- where they read?

- why they read?

Choose one of the learning to read accounts that is most similar to your own experience of learning to read and record in your notebook.

Discussion

Who? Did it surprise you to see how many different people were mentioned as being key people in helping these individuals learn to read? One person remembered an inspirational teacher. Others talked about members of their family who had taught and encouraged them. Sometimes this was their mother or father, but also older siblings or a grandparent. People of different ages can help children learn to read. As teachers we are a vital part of this process.

What? Learning to read can draw on a range of resources. This includes books but is not limited to only school textbooks – listening to stories, learning words from memory and reading words in the market are just some of the ways mentioned in these accounts that can help children to read.

Where? Learning to read can take place in a classroom but also at home, in the street or village. A library may be a special place that encourages a love of reading. Children may begin to read in one place, but they will learn more easily if they are encouraged to read at home and in school and in their community.

Why? Children can start to learn to read out of curiosity, for example seeing an older sibling reading. There are also examples in these accounts of older brothers or sisters wanting their younger siblings to do well at school. In some of the accounts, reading is an important part of family life.

It is important as teachers to think about reading not just as a skill for children to learn but as a process that involves people and things around us. It is a unique part of our own history: how we learned to read helps to make us who we are.

Our approach to learning and teaching early reading

The approach we have taken on this course to learning and teaching reading is a balanced one. This means that we believe that being able to read involves:

- understanding that print carries meaning

- knowledge of letters and sounds to recognise letters and words

- comprehension of what’s been read.

This requires:

- children who are motivated to read

- children who are able to make connections between what they have read, their own lives and other texts they have read/listened to

- teachers who have a range of different approaches and methods to help children to master different aspects of reading.

Research has shown us that there are two equally important strategies in learning to read:

- ‘bottom-up’ skills where children use their knowledge of letters and sounds to read or decode whole words (but without necessarily understanding what the words mean)

- ‘top-down’ strategies where children use their personal and cultural knowledge, their prior reading knowledge, and the overall meaning of the text they are reading, to predict words and sentences.

Some children respond well to one approach more than the other; however, all children benefit from a combination of the two, which is known as a ‘balanced’ approach.

Some activities we will introduce may at first seem unrelated to reading and writing, but they are important aspects of cognitive development for literacy. Neuroscience shows how cognition – or thinking – involves a person’s physical, emotional and environmental states, multi-sensory experience, and imagination all at the same time (Gimenez et al., 2014).

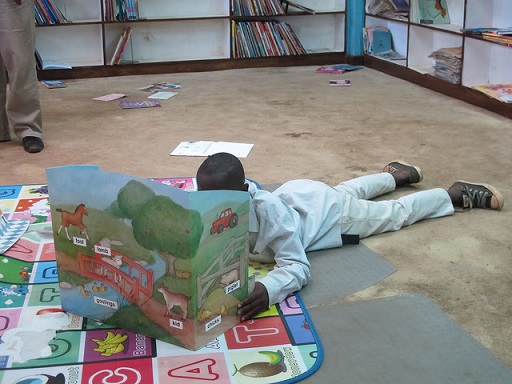

Activities that develop basic concepts about position and shape, or that build motivation, are important processes that are essential for literacy. Research shows that children who do not acquire these skills in the early stages of becoming literate are likely to struggle to progress (Boursalou, 2008). In order to develop successfully, children need opportunities to develop their fine motor coordination and balance through activities such as painting, drawing, working with clay, throwing and catching, or skipping with a rope.

Also, activities that develop basic concepts about position and shape, or that build motivation, are important processes that are essential for literacyearly reading development.

Activity 1.4: Reflecting on learning strategies

Write brief notes on these questions and discuss them with a colleague:

- Think about two children who you have taught to read. What worked best for them – a ‘bottom-up’ or a ‘top-down’ approach?

- Why did one approach or the other seem to work best for the particular child?

- In your classroom, do you spend more time on one approach or the other in your own teaching? What are your reasons for this?

- Outside of reading lessons, are there other subjects where you use ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up’ approaches?

- Think about one of the ideas introduced in this section and apply it to a child you know. What type of reader are they? Who do you think helped them to read?

Discussion

All children learn to read in different ways. You may have found that some children find it easy to read or decode individual words, while others need the context of the word within the sentence to fully understand the meaning.

The implication of a balanced view of reading is that reading activities should not be confined to particular lessons, and that teachers should use a variety of approaches. Numeracy, life skills, creative arts and physical education all provide opportunities to support reading.

In the rest of this course you will consider:

- how to create a literacy learning environment

- what teachers can do to help prepare children to learn to read (pre-reading activities)

- specific methods for teaching reading

- how to make best use of stories and books

- how to assess reading and plan how to move children forward.

Each section of the course is underpinned by a balanced approach to teaching early literacy and the belief that children need to be actively engaged in the learning process.

A question of language

By the time they leave primary school, many African children are being taught in English. In recent years, however, it has been suggested that children should be taught to read and write in their home language, making the transition to English in around Grade 4. There is convincing evidence that children who can read in their home language progress much faster in English, and are more likely to be successful in later years of schooling (Kioko et al., 2014).

When children learn to read and write in their own language, they learn more quickly. This is because they are already competent speakers of their home or first language. They can use their first language knowledge to predict or make ‘educated’ guesses of the meanings of a new language. In this way children are more likely to become natural writers and readers, just as they are natural speakers. This means that it is easier for teachers to design active lessons that link learning in school to children’s home life.

Teachers are also more flexible and creative when they can use their first or home languages with their children. Research has shown that teachers who use only the school’s medium of instruction are less active and creative in their teaching (Barrett et al., 2007).

There is much evidence that flexibility in moving between home language and other languages allows teachers and children to maximise understanding and participation (for example, see the OpenLearn course Language as a medium for teaching and learning.

Learning other languages is easier when literacy is first firmly established in the most familiar language (Cummins, 2001; Unicef, 2016). Academic research also documents the advantages for the brain and education when children learn to read in their most familiar language (Ouane & Glanz, 2011).

Activity 1.5: Reflecting on ‘A question of language’

Record three things from the reading in your study notebook that you either found interesting or that was new information to you.

You are now going to apply your knowledge from the reading to analysing a case study (Case Study 1.1) about the importance of the home language in supporting children’s early reading, and then try the activity that follows it. We suggest you try this with a colleague, if possible.

Case Study 1.1: Home language in early reading

Mr Shabukali’s son, Matson, has just started school in Lusaka. Mr Shabukali is concerned that Matson is being taught to read in their home language of Nyanja – he had expected that Matson would learn to read English. He has gone to the school to meet the headteacher.

Activity 1.6: Home language or English?

Having read the case study, imagine you are the headteacher. Write a short paragraph explaining to Mr Shabukali why you are teaching Matson to read in Nyanja. Draw on your own experience, your response to Activity 1.5 and the notes you made in your study notebook.

Optional readings: If you are interested in learning more about the importance of home language learning there are two studies you can read.

You can download a major UNESCO study on the issue. Pages 22–3 have an executive summary that is easy to digest. The conclusion and recommendations (p. 214) might also be of interest.

A Multilingual Education article that documents success stories from Africa in which mother tongue education has brought educational and economic benefits.

Optional activity: You may also want to download and read an OER on a multilingual classroom from the TESS-India project.

Looking at effective teachers of reading

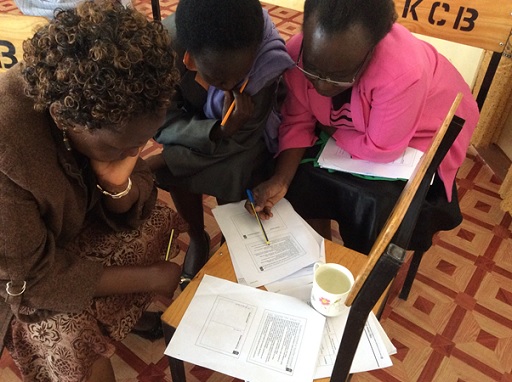

Activity 1.7: An example of good literacy teaching

Part 1

Teaching literacy effectively requires a considerable range of skills. As you read the next case study (Case study 1.2), write down:

- all the things that the teachers do to support literacy

- what the children actually did in the lesson.

Case Study 1.2: An example of good literacy teaching

The Grade 1 teacher Juba was talking at the end of the day with a colleague Tabitha.

Part 2

Having read the case study, can you identify which parts of the lesson you already do? The children’s active participation in the lesson provides informal opportunities for the teacher to assess the children’s early reading development. Record in your study notebook one area of assessment that the teachers could choose to focus on.

Answer

Both the children and teacher learned a lot in this lesson.

The teacher:

- talks to a colleague to reflect on her experience and share ideas for improving the lesson

- invites someone from the community into the class to help her

- creates the opportunity for children to talk and share ideas

- encourages the children to think of and use physical actions to match the words they had chosen

- encourages children to think of new words that they could act out

- uses resources (proposing another story and planning to bring in a box)

- chooses a context for the activity that is familiar to children

- selects an activity that combines top-down and bottom-up approaches to reading

- informally assesses the children throughout the lesson.

The children:

- are all included

- listen carefully to each other

- think of different words

- make up actions to match their word

- use rhythm and rhyme

- talk with each other

- enjoy the lesson

- are actively engaged in their learning

- can make links with prior home experiences of storytelling.

This culturally relevant activity enabled all children to be actively involved and engaged, and we can imagine how much the children would have enjoyed this type of reading activity.

Something to think about: In your own teaching, how often do you do any of the things that teacher Juba did? What are you teaching next week? Which of these strategies could you use to make the lesson more enjoyable, help children learn to read more effectively, motivate children to want to read, etc.

Case Study 1.2 illustrates some things that teachers can do to support early reading. The prospect of being responsible for teaching a large class of young children to read can be very daunting. But if you talk it through with colleagues break it down into simple steps, it becomes more manageable.

Where do reading activities fit into the weekly timetable?

Teaching early reading to young children requires activities that allow the children to:

- play an active part

- use their bodies and voices

- draw on everyday experiences to help make connections between what they’ve read and their own lives.

Short activities repeated throughout a week can help young children by reinforcing what they have been learning. This is something that you read about in Case Study 1.2, as Juba was planning to build on her lesson the following day.

On your timetable there will be specific times dedicated to reading. However, reading activities don’t need to be limited to literacy times – subjects such as numeracy or life skills could provide opportunities for literacy development. For example, if children are learning about personal hygiene in life skills, you could emphasise the words for the different parts of the body. Alternatively, you could use a counting story to practise numbers to 10.

Activity 1.8: Planning for early reading

Have a look at your weekly planning for next week, see if you can find any stories that you could use in other subjects during the week.

As part of your planning, it helps to have a timetable of lessons and activities to make sure that children develop the different skills necessary for early reading. This planning should be done with other foundation teachers at your school so that you can share ideas and resources. If your class is taught by other teachers as well, make sure you work together to plan reading activities, whatever the subject.

Here is an example of a daily timetable for Early Childhood Development teacher Doreen. At this level, every day follows the same pattern.

Working with a partner, add more detail to this plan, making sure that the day includes a variety of reading-based activities. As well as stories, a wide range of different kinds of activities can be used: songs and games are a good way to get children reading. You could include specific songs, stories and resources you might use, or games you might play. Make a note of the resources you would need.

If you have your own class, you could do the exercise using your own daily or weekly timetable instead.

Discussion

Your planning can start at a very general level – for example, what you want the children to achieve by the end of each term – and then you can work on the details for each month in a term, and each week in a month.

Alternatively, you could plan from the details of a weekly timetable, and then build up to monthly and term planning. Some people work best thinking of the ‘big picture’ and then working down to the details; other people like to start with the details and then work up to the bigger outcomes.

Each week it is sensible to develop the habit of carrying out an audit of the language and literacy activities completed that week. This will ensure that you maintain a good variety of activities, over time.

How much have you remembered so far

Activity 1.9: Reflecting on your learning so far

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Answer

True: When young children use tools such as writing materials, it activates areas of the brain related to the development of literacy. Activities that encourage fine motor coordination and balance – such as painting, drawing, working with clay, throwing and catching, or skipping with a rope – may seem unrelated to reading and writing, but are important aspects of cognitive development for literacy.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False: Children become better readers in the long term if they learn to read in their home language. It is helpful if family members can encourage them with English as they move up the school.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Answer

True: All subjects provide opportunities to practice reading and writing.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Answer

True: A balanced approach gives all children the opportunity to learn.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

Answer

False: The reality is that children learn to read in many different ways. Practising reading with family members is very helpful for young readers.

Moving forward

In this section we have shown you how the Teaching early reading in Africa – with African Storybook course works and encouraged you to think about how to organise your learning. You have had the opportunity to reflect on the fact that literacy in general and reading in particular don’t only take place in school, and to consider what learning to read might be like from the perspective of a child. You have begun to think about what effective teachers of literacy need to be able to do.

In the next section, the focus is on how to create a stimulating, print-rich learning environment for your children and how to access resources to help you be an effective teacher of reading.

Now move on to Section 2, ‘Creating a language-rich learning environment’.