Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 20 February 2026, 9:21 AM

Section 3: Preparing to learn and teach early reading

Introduction

This section presents ideas and resources that can be used to help children develop their early reading skills through:

- asking and answering questions

- thinking about daily routines

- looking at pictures and responding to them

- physical movement

- songs and rhymes.

Throughout, the emphasis is on speaking and listening.

You will:

- consider how asking children questions can develop thinking skills

- explore how to develop children’s speaking and listening skills through using pictures

- understand the contribution that physical movement makes to early literacy.

As children move into learning how to read, it is important that they are given a range of opportunities to talk with you and with each other. Speaking and listening underpins the successful development of their early literacy skills.

Children enjoy and learn through play and they also learn through experimentation, exploration, and trial and error. Songs and rhymes based on the children’s own everyday experiences (such as shopping, or travelling to the market) are useful, because they draw on shared experiences while supporting early literacy skills.

Through active participation, such as asking and answering questions, children will also develop thinking skills. Instead of listening to the teacher and memorising answers, children are required to verbalise their thoughts aloud. In reading lessons, children need to talk about the story, predict what happens next and answer questions.

The more enjoyment and enthusiasm for reading you can generate among the children, the more your class is likely to want to learn to read – you are a reading role model for your classes. In Section 1, you reflected on your own experience as a reader and writer, and how you use literacy in your daily life. As a teacher, it is important that your children see you reading and writing, and that you become a role model for them.

In this section we focus on how the four specific strategies to support children’s early reading development:

- everyday routines and activities

- using pictures to develop speaking and listening

- using physical movement to support early reading

- songs and action rhymes for reading.

We start by learning more about comprehension and developing thinking skills.

Developing comprehension and thinking skills through questioning

Young children need the security and memory-building that comes from repeated activities, stories, games and songs – all of which support the development of early literacy skills.

But they also need their minds to be constantly challenged. When children are learning to read, asking questions helps them to make meaning or comprehend what’s been read.

The purpose of reading is to understand what’s been read. Young children do this by listening to the teacher read and joining in with familiar words and phrases. They can then answer questions about what’s happened or what they think might happen next, such as ‘Who knocked on the farmer’s door?’ or ‘What animal do you think has eaten all the maize?’. As children learn to read independently, they can ask and answer each other’s questions, as well as answering the teacher’s.

Even very young children can benefit from being asked questions in every lesson, and there are lots of ways of doing this. You can ask questions that encourage young children to think and talk about their lives and ideas. You can also ask questions after you have told or read a story – asking questions encourages children to develop their comprehension skills, a key skill for reading.

Comprehension questions can mainly be divided into two types: closed and open-ended.

Closed questions

Closed questions can test children’s knowledge, memory or understanding of what’s been read. Examples include:

- How many legs does the rat have? (Answer: four)

- What was the name of the main character in the story? (Answer: Bongani)

Closed questions are useful because they:

- have just one answer or a small number of possible answers

- develop children’s confidence that they may know the correct answer

- can indicate to the teacher how much each child understands – this is especially important when children move from learning in their home language to learning in English

- can sometimes show a teacher what a child doesn’t know, so a teacher can plan to do extra teaching

- can be asked to individuals, pairs or groups, or for a whole class to chorus the answer.

Open questions

Open questions encourage thinking, imaginative and reasoning skills. Examples include:

- What would it be like to be the frog in the story? (Possible answers: I would have to hop to school! I wouldn’t need any shoes! I could jump over the school gate.)

- What do you think Bongani is doing in this picture?

Open questions are useful because they:

- have many possible answers

- allow children to be imaginative with their answers and use their personal or cultural knowledge to answer

- encourage a wide use of vocabulary

- encourage children to give reasons for their answers ( using the word ‘because’) and think about causes and effects

- ask children to return to what they’ve read to provide reasons for their answers

- can be a challenge to very able children

- are a good opportunity for children to work together in pairs or small groups to think of their answers.

Activity 3.1: Thinking about questions

The table below shows some closed and open questions that a teacher might ask young children in a reading lesson. Notice the different ways that closed and open questions are phrased, and how the open questions lead to longer answers. These types of questions give children an opportunity to think more deeply.

In your study notebook, fill in possible answers to each open question (that a 5–6-year-old might give). Then add a question and answer of your own.

| Closed questions | Open questions |

|---|---|

| Is that a lion or a cat? | What’s the difference between a lion and a cat? |

| Answer: It’s a cat | Possible answers: A lion is a dangerous animal and a cat is not. A lion is a bigger type of cat. I like cats but I don’t like lions. |

| Is it raining? | How do you know it is raining? |

| Answer: Yes, it’s raining. | |

| What is the boy in the picture doing? | What do you think will happen next? |

| Answer: He is running to school. | |

| Where is the girl hiding? | Why is the girl hiding? |

| Answer: She is hiding behind a tree. | |

Questioning in the classroom

In Case Study 3.1, Patrick uses a picture storybook to get his class thinking by asking different kinds of questions. As you read the case study, think about how you can use these ideas in your early reading teaching.

Case Study 3.1: Using questioning in the classroom

Patrick teaches at a school not far from Kigali. Unlike any other countries in Africa, almost everyone in Rwanda speaks one language: Kinyarwanda. He is a qualified and experienced primary teacher, although he has not taken any early childhood education qualifications, which have only just been introduced into pre-service courses at teacher training colleges. Teaching at pre-primary level is something that has only recently become widespread in Rwanda and schools lack resources for early childhood development (ECD).

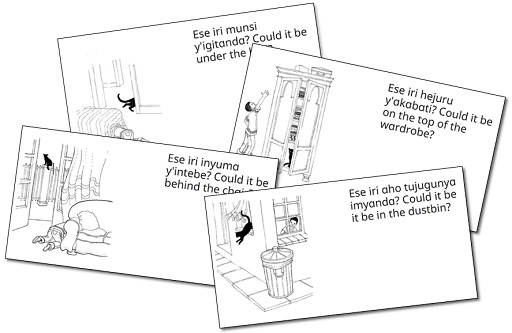

Patrick has also recently come across the ASb website and wants to try and use a storybook in his class in order to extend the children’s thinking and speaking skills. He chooses the storybook Where is My Cat?, because it has very simple pictures with a repeating pattern in the text. It is also full of questions and opportunities for children to express their own ideas. It is available in both Kinyarwanda and English, and Patrick thinks he can use it in many ways to develop his children’s early reading skills.

Having downloaded and printed a copy of the book, Patrick brings all the children to a sitting space at the front of the class. He wants every child to be involved and brings them close to him so that they can all see the book and he can glance around and catch every child’s attention. All of his children are very excited.

Patrick decides to introduce the book by showing only the title page, which has no writing. He sits on a chair, shows the first picture and asks a closed question: ‘What animal is this?’ All of the children can answer that it is a cat. He asks another closed question: ‘What colour is the cat?’ Nearly all of the children are happy to chorus that it is a black cat. He asks some more closed questions: ‘Can you see the eyes?’ ‘Can you see the legs?’ All of the children are able to answer.

Then Patrick decides to ask an open question: ‘What do you think this story is about?’ He expects lots of hands up, but no one wants to answer. There is silence. He realises that there are lots of possible answers to this open question, and no child wants to get it wrong!

He decides to ask the children to hold hands with one neighbouring child: this is their talking partner. He tells the children they can talk over the question with their talking partner. He again asks: ‘What is this book about? What is the cat doing and what happens to him or her? Talk it over with your partner. I will raise my hand when I want you to stop talking.’

All the children begin talking to their partner about what the book can be about. Patrick moves around the pairs listening in to their conversations. When he thinks that all pairs have had a good chat, he raises his hand to stop the talking and asks the children to raise their paired hands if they have thought of an answer.

Patrick is delighted! Now nearly all the pairs of hands are raised. Even children who normally never put up their hand are happy to do so with a partner. The children have thought of lots of possible answers:

- ‘The cat is hungry and wants some food.’

- ‘The cat is lost and is looking for his home.’

- ‘The cat is lonely and wants a friend.’

- ‘The cat is a mummy who has lost her kittens.’

Some children even think the book will be about lots of animals of different colours. The children have thought of these imaginative ideas by working in pairs and Patrick is very pleased with how much thinking and speaking has taken place in his classroom. The storybook has really captured their interest: the children are now very curious to find out what the story is really about …

In future weeks, Patrick is able to read the whole book to the children. Because it has repetitive text, the children begin to know it by heart and are able to:

- answer the closed questions on every page (such as ‘Is the cat under the bed?’ ‘NO!’)

- think of a name for the cat and imagine where it is going in between each picture

- draw and cut out a cardboard cat and furniture to use as props as they retell the story.

Eventually Patrick is able to use this storybook to introduce reading skills. (See Section 4 for different approaches to teaching reading.)

Patrick’s reading lesson was very successful. By asking both closed and open questions, he was able to encourage the children to think about the story, and could identify which children had understood the question.

Activity 3.2: Reflecting on the case study

Read Case Study 3.1 again with a colleague and write down in your study notebook the different strategies that Patrick used to encourage active participation. Some initial suggestions are that he:

- gives the children time to think

- creates talk partners

- chooses an interesting story.

Discussion

Patrick is a very effective and skilled reading teacher. He also knows his children well and is confident in letting them talk to each other. He employs many strategies – how many of these did you have on your list? The different strategies that Patrick used to support the children’s early reading skills included:

- developing comprehension skills

- sharing ideas about the story with their friends

- practising reading the repetitive words

- enjoying listening to the story

- joining in with Patrick as he reads.

You may have written down more ideas. Find some time to discuss these strategies with a colleague, and then choose one to try out in a reading lesson next week.

(With simple books like this, if you are not able to print them then perhaps you could copy them on to large pieces of paper to share with the class?)

In the next activity you’ll return to the storybooks you looked at in the last section of the course.

Activity 3.3: Asking questions

In Section 2 you downloaded three stories from the African Storybook website. Re-open these stories, skim-read them and choose your favourite one.

You are now going to write six questions about the story that you could ask the children in your class. You can fill in this template and print it out or you can write your questions in your study notebook. Think about using both closed and open-ended questions, returning to Patrick’s story in Case Study 3.1 if you need to.

Children’s everyday lives as a resource for reading

How can the everyday activities that children are already familiar with be incorporated into your teaching of early reading?

Activity 3.4: Everyday experiences

What everyday experiences can children already talk about before they come to school? How can these experiences be used to support early reading?

On your own, or with a colleague, think of at least three examples. Note your answers in your study notebook and compare them to the discussion below.

Discussion

Young children will already be able to talk about many aspects of their home lives, including friends, family, food, playing, animals, weather, toys, emotions and traditional tales.

Teachers can use these experiences to stimulate speaking and listening activities in the classroom that can support early reading. Choosing storybooks based on these familiar experiences, for example, makes connections between the words, letters and sounds found in books. It also helps children to appreciate that stories in books reflect their own lives – this can be very motivating.

Children can also be encouraged to retell the small stories of their lives, for example, telling the story of their journey to school or a trip to the market.

You can choose books and stories that you know will be meaningful to the children in your classes. Return to the ASb website and select a story that you know your children will relate to. Find time in the week to read it to them and notice their reactions. Did they enjoy the story? Did you enjoy reading it and talking about it? Encourage them to learn the story and share it at home. Do they have family routines they could tell you about?

How did you select a storybook? You may have looked at the words first and thought about the story, or you may have chosen the storybook because the pictures were engaging and interesting. Next, you are going to learn more about the importance of pictures for early reading development.

Using pictures to support early reading skills

Having selected a storybook you think your children will enjoy, reflect on the decisions you took to make your selection.

Children who are ready to learn to read will begin to explore the relationships between objects, pictures, sounds, letters and written words.

When we are adults, we take for granted how important the combination of words and pictures is to help us make sense of things. We read newspapers with photographs, we see illustrations on signs, we notice images and labels on posters, and we recognise logos on food labels. You may know children in your classes who are able to recognise long before they can decode letters and sounds in books.

A good way to help children grasp the relationship between images and words on a page is through the use of pictures and picture books. Some children will have enjoyed sharing picture books from an early age at home, but others will have had limited access to any books. As their teacher, you need to think of different ways to give every child the opportunity to enjoy the experience of picture books. Pictures are a very important part of telling a story, and for early readers the pictures are useful in helping to remember the sequence of the story and ‘what comes next’.

You may already use pictures in your lessons – drawing three simple pictures on the blackboard, for example, to show the beginning, middle and end of a simple trip to the market. Children are then encouraged to retell the story in simple sentences: ‘I went with my brother to market. We bought maize and coffee beans. Mama was happy.’ This simple starting idea can be extended and made more interesting:

- The children could work in small groups to act out their story, adding details and characters that they meet along the way. Their excitement and enthusiasm for these stories can be greatly increased by adding sounds to the story: footsteps, knocking on a door or speaking in different voices for each character in the story.

- You could also read a local traditional tale aloud and ask the children to draw pictures to match the story as you read. They can then share their pictures with each other, make up their own stories and perform them.

- Create picture cards from a favourite story – you can download pictures and print them out, find pictures in magazines or newspapers, or draw them. A storybook like Look at the Animals has some easy pictures to copy. Hand out the picture cards and ask the children to hold up their picture when you tell their part of the story.

Discuss these ideas with colleagues and choose one to try out in your classroom next week.

Activity 3.5: Using familiar themes to support early reading

Choose a story you know well that features animals, or choose one from ASb. For example, A Little Girl – a storybook that has been translated from isiZulu into English – tells the story of a girl who travels through the forest to visit her grandfather. Along the way, she meets a careless goat that warns her about a meeting of the animals in the forest.

Part 1

Write down in your study notebook the reasons why animals are a good starting point for encouraging early reading development. Compare your answers with the discussion below.

Discussion

Animals are fun because children are already familiar with a variety of animals and the sounds they make, and children enjoy drawing. Many traditional tales feature animals.

Part 2

Choose one of the following picture story themes that you could use with young children: family, food, home, clothing, village, people’s jobs, vehicles, household objects or games.

Now answer the following questions in your study notebook:

- How could you use them in a story?

- What actions or sounds could you add? (Ask the children for their ideas.) Make four picture cards for your chosen theme and make notes of how you could use the cards with your class. Alternatively, you could download examples from the ASb website, such as Look at the Animals.

- Write your own story, which you will read to your children. Write one simple sentence for each of your four picture cards. Add detail about the characters, the setting and the plot.

If you get the chance, try these activities out with your class and note down how the children respond. Talk to a colleague about how the activity went.

Now read Case Study 3.2 and try the activity that follows it.

Case Study 3.2: Salome’s new class

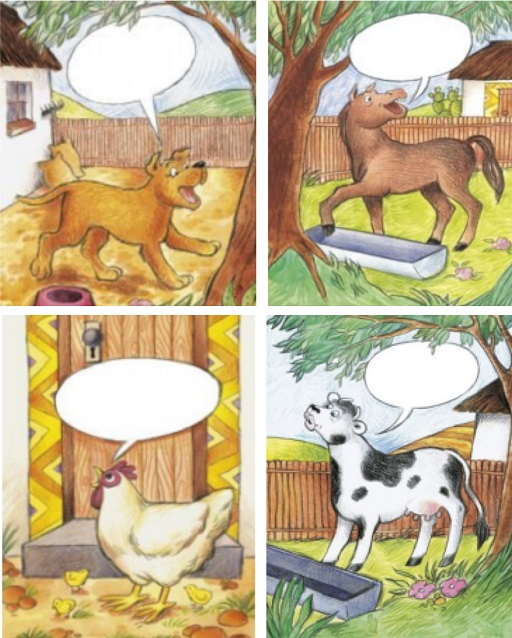

Salome has just finished her diploma training, where she specialised in early childhood education, and she has been posted to a school in northern Ghana. She thinks that there will not be many resources in the classroom, so she takes with her a set of laminated picture cards she made at her college. These pictures can be arranged in different ways to tell stories, especially stories she has learnt from her own grandparents, which she notes down in her notebook.

Salome speaks some Dagbani, one of the 11 official languages in Ghana, though it is not her own first language, so she knows that she will have to translate the stories and games. On her first day in her new school she has a large class of children, and she uses just three or four of the laminated picture cards to teach the children in Dagbani. Her teaching focuses on the vocabulary of local animals and the noises they make. The children really enjoy hearing the noises and Salome encourages them to make the noises along with her.

She goes through the names of the animals again, and the second time, when it gets to the animal noises she waits for the children to see if they can remember the noise and join in. This time she tells the story Look at the Animals and the children join in with the noises. The children have enjoyed the story and they have participated by making the sounds. As she told the story the first time, Salome said the name of each animal. The next time she reads it, she points at the picture of the animal and the children say the animal’s name and make its noise.

Salome also decides on a new activity. She divides the class into small groups of three or four, and each group moves to a different part of the room. She then whispers to each group the name of a (new) animal and gives them a prepared card with the animal name and picture. She gives each group a couple of minutes to decide what noise their animal makes. She has chosen some familiar animals, such as a snake, elephant, cat, monkey, hippo, dog, lion, goat or chicken, and the group makes their noise.

Salome uses the animal words and pictures to retell the story Look at the Animals. She gives groups of children three pictures each so that they can begin to make their own short spoken stories.

She will make time to tell the story again later in the week and hopes the children will be able to remember some of the noises. The following week, when they go through it again, she will ask the children what the noise is for each animal. After that she will put the word for each animal on the board in Dagbani and ask the children to make the noise when she points to the word.

Activity 3.6: Using picture resources

With a colleague, identify what Salome does to support:

- vocabulary development

- picture/text connections

- reading for enjoyment

- home language learning

- participation

- inclusion.

Record your ideas in your study notebook.

Using physical movement to support early reading

Children like to play games. Many of the games they play – especially those with songs, rhymes or actions – help them to practise early reading skills.

Learning songs and joining in are important foundations for the development of children’s early literacy skills. These experiences provide the building blocks for early reading development and encourage active participation.

In order to become effective readers, children first need to be ready to read. Factors that influence children’s readiness to read include:

- having an interest in becoming a reader

- listening carefully for meaning and follow and imitate sounds, practising fine motor control in hands and fingers

- developing spatial awareness and whole body coordination.

Games to support readiness for reading

Examples of games that support early reading readiness include the following:

- Listening and speaking skills:

- learning rhyming songs by heart (hearing and predicting rhyming words is a predictor of reading ability)

- clapping a rhythm, listening for syllables

- singing rhyming songs

- listening to an joining in with simple stories

- matching to words

- using cardboard boxes, etc. for imaginative play.

- Fine motor skills:

- hand/eye coordination

- finger rhymes

- table games with paper, scissors and glue

- outside play with stones, water and cutlery.

- Spatial awareness – whole body coordination:

- throwing a ball around a group during a rhyme

- making large actions to a rhyme or song

- running, jumping, dancing games.

- Classroom cooperation:

- clapping games in pairs and hearing syllables

- ‘follow my leader’-type games to support recall of information

- circle games, such as passing a toy around a group.

All of these games support children’s readiness for reading. Sally Goddard Blythe (2000) argues that even though learning takes place in the brain, it is a child’s motor skills that evidence the developing maturity of the body and brain relationship, expressed through movement, balance and posture. Reading is an oculo-motor skill: being able to track words on a page is connected to the motion of the eye. She argues that a child who is better coordinated has fewer learning problems. Incorporating physical movement and promoting coordination in lessons through games will support children as they begin to develop their early reading skills.

(You may like to read Sally Goddard Blythe’s article in full.)

Now read Case Study 3.3 and try the activity that follows.

Case Study 3.3: Songs and action rhymes

Innocent is an experienced early primary school teacher in Tanzania who has recently begun mentoring two new teachers, Sarah and Cornelia, in the new pre-primary unit that has opened at his school. He lives in Mbeya and his first language is Bemba, although he also speaks both English and KiSwahili. Innocent knows that, as new teachers, Sarah and Cornelia do not have a lot of confidence in working with pre-primary children.

He decides to focus on simple local games – especially the kind of games that have songs or rhymes attached to them – as a way to encourage both teachers and children to make the transition from speaking and listening to reading and writing. He knows that games are a good way of making learning fun and that the ability to hear and predict rhymes will develop children’s reading and writing skills.

One game involves getting all the children to stand up and to each find a little space for themselves (as they will need to do some bending over) and to then follow the actions of the teacher as she sings. As she names each part of the body, she touches it. So she taps her head with one hand, then she taps her shoulders with both hands, then her knees and then her toes with both hands and each time she sings the word.

Head, shoulders, knees and toes, knees and toes,

Head, shoulders, knees and toes, knees and toes,

Two eyes, two ears, one mouth and one nose.

Head, shoulders, knees and toes, knees and toes.

The children really enjoy playing this game and singing this song because it:

- focuses their attention and practises vocabulary

- contains rhyme and repetition

- helps physical coordination by practising bending, stretching and two-hand coordination

- helps children to remember ones and twos and matching pairs (ears, eyes, knees and shoulders).

Sarah and Cornelia follow up this song with others they know in Bemba and KiSwahili.

Activity 3.7: Professional staff development

How could you explain to a colleague why an activity like the one in Case Study 3.3 would be useful in supporting early readers? Look back over the last few pages and summarise your ideas about physical movement can support early reading in your study notebook.

Ask your Principal if you can host a ‘readiness for early reading’ staff meeting:

- Briefly explain what you have learnt about getting ready to read and the benefits of action rhymes and songs.

- Use the meeting to teach each other new songs.

- Make a collection of good action songs for early learners and make them into a big book for the staffroom.

- If you can access the internet, search for ‘Action rhymes for young African children’ for new ideas to try with your class.

As well as helping develop co-ordination and vocabulary, songs can help children develop phonological awareness.

Songs and action rhymes for reading

Children come into your classrooms listening and hearing sounds in their environment. This is called phonological awareness.

You can help children to develop this awareness by taking them on a listening walk – into the yard, for example, and asking them to listen out for sounds. What can they hear? You may have cattle in the field next door or community leaders meeting outside the school fence. Maybe there’s a road nearby, or children playing.

Asking children to ‘tune in’ to the different sounds and then – very importantly – asking them to point to where the sound is coming from is a crucial skill in learning to read. Being able to hear different sounds in the environment is the step before being able to break down sounds in words into their smaller parts. It’s also rather fun to go outside on a listening walk. Alternatively, this can be done in the classroom with objects that make sounds, such as a rattle made of bottle tops.

Learning songs and joining in are important foundations for children’s early reading development. Songs and rhymes build children’s internalisation of rhyming strings. The ability to hear and predict rhymes is a predictor of reading ability. Choose songs and rhymes with words that you break down into sounds before building them back up again. Activities like this help children to feel confident in playing with letters and sounds, and supports their understanding of how words are put together.

For example, choose a song or rhyme about a cat. At some point in the rhyme, say ‘CAT’. Then break it down into its three sounds, ‘/C/A/T/’, and then build it back up again to say ‘CAT’. The children can try and say the word all at the same time – this makes it fun and engaging. Try this with other simple words before moving onto words like ‘DUCK’. This is a word with four letters (‘D’, ‘U’, ‘C’, ‘K’) but only three sounds (‘/D/U/CK/’). At this early stage, you want children to learn about the sounds within words. Fun songs and rhymes are a good way to do this.

Something to think about: How many games do you already use in your classroom? How would you explain to a parent who thinks their child is just playing that games like these play an important role in preparing your son or daughter for reading and writing?

Activity 3.8: Using songs and rhymes

Download and/or read a section of a TESSA OER on using songs and rhymes. Share this with your colleagues. Ask them to discuss the case studies and activities in pairs, and then share two reflections or thoughts with the wider group. (Anyone who has a smartphone will be able to access this resource on that.)

Finding a good storybook

Most children love any story. We want children to have good storybooks so they learn to love telling stories and reading.

You can find many storybooks using the African Storybook Reader app. In the next activity you will use this app to find a story and then decide if it is a good storybook for your children.

Before you do the activity follow these steps to download and get started with the African Storybook Reader app:

Download the free African Storybook Reader app from Google Play or the App Store. Install the app on your phone or tablet.

- Go to EXPLORE to find storybooks to save in your LIBRARY.

- On the EXPLORE page, choose a language. Tap in the white spaceat the top of the screen to open the Language list. You can also open the Language list in the MENU (tap on the three dots at the top right of the screen).

- Select the language that you want for storybooks.

- The App will list all the storybooks in the language. You can organise the list by TITLE (alphabetically), by DATE (when it was published) or by READING LEVEL. You can search the list of storybooks by typing a key word or words.

A downloadable resource on how to get started with the African Storybook Reader app is available from Downloads: additional resources on the course content page.

Activity 3.9 A good storybook

- Find any storybook using the African Storybook Reader app.

- Read the story to yourself or out loud.

- While you are reading, write down some reasons why you think this is a good storybook, or not a good storybook.

- Share your ideas with your colleagues, discuss together and make a list of what you think makes a good storybook for young children.

- Read our list in the discussion. Did you have anything different on your list? What would you add to your list now?

View discussion – Activity 3.9:

Discussion

A good storybook:

- is enjoyable.

- is authentic because it relates to children's contexts and realities.

- has good illustrations that support the text, and that may also suggest other meanings or feelings and extend the text.

- is not necessarily ‘real’ but is logically developed. In other words, make believe that is believable or nonsense that makes sense.

- has interesting language – rhyme, rhythm, repetition, word play.

- has suspense (or danger) to encourage children to say, ‘What will happen next?’ or ‘What if…?’

- has something unexpected, against the rules, or a ‘twist in the tail’.

- has a beginning, middle and end.

In the next activity you will practise using these criteria so that you can become an effective critical reviewer of storybooks.

Activity 3.10: Which stories do Children enjoy?

- Choose another storybook of your own or in the African Storybook Reader app. Download a copy of this table or copy it in your notebook and use it to review the storybook.

| Name of storybook: | |

|---|---|

| This storybook… | Review comment |

| Is enjoyable because… | |

| Is authentic because… | |

| Has good illustrations such as… | |

| Is logically developed because… | |

| Has interesting language like… | |

| Has suspense (or danger) when… | |

| Has something unexpected when… | |

| Has a beginning, middle, end | |

When you have a chance, read the same storybook to children. How will you know if they enjoyed the story? Ask them questions such as:

- a.What was your favourite part of the story?

- b.Which pictures did you like/what did you like about them?

- c.Which part of the story made you feel happy/angry/surprised, etc.?

- d.Which word is most interesting for you?

- Now you know what the children think about the storybook, would you choose to read it with them again? Why/why not?

As you read more storybooks, you will get into the habit of critically reviewing them by using the criteria in Activity 3.10. Also listen to your children. Let them tell you why they did or didn’t like a story. This will help them to choose books as they become fluent readers.

Planning a classroom activity

In this final activity, you are asked to plan a classroom activity to help children get ready to read. You can plan an activity that uses pictures and questions, or songs, rhymes and games.

If possible, incorporate pair work in to your activity. This is an easy way to get children talking, even if you have a large class. You may find this TESS-India key resource on pair work helpful as you think about how to organise the activity in your class. Work with a colleague and critique each other’s plans.

Activity 3.11: Plan a classroom-based reading activity

Look back through the section. You could base your activity on a picture or object that you bring into the class, a new song or rhyme that you have learnt, a storybook that you have in your classroom, or a storybook you have downloaded in the African Storybook Reader app.

Think about how you could use closed and open questions to promote thinking, or actions to help develop co-ordination skills. Your activity might be short, so think about how you could develop it into a whole lesson, perhaps linked to a topic that you are teaching at present.

If you have the opportunity, try your activity with a class and evaluate it by answering the following questions in your study notebook.

- Did the children enjoy the activity?

- Did this activity help children to develop their early reading skills? If so, which aspects? For example, vocabulary development, speaking and listening skills, spatial awareness, fine motor skills?

- Did all the children take part in the activity?

- What would you do differently next time?

Assessment

In the following activity you will share a resource, idea or activity that you have developed while studying Sections 1–3 of this course.

Activity 3.12: Assessment

You will complete this activity by uploading content to Teaching early reading in Africa’s course website.

Reviewing stories

Find a Level 1 or 2 storybook on the ASb website in a language that you read. Go to the area on the course website for this Activity 3.12, click on the ‘New blog post’ button and do at least one of the following:

- Give the title, language and level of the story you have chosen.

- Write a short review of the storybook. Use the same review table you used in Activity 3.10 and say why you will or why you will not read this storybook with children. You might also suggest how you could adapt it.

- Rate the story out of 5 (5 is excellent) in line with your review.

Moving forward

In this section you have further developed your content/subject knowledge for early reading. You have learned about the types of questions that support reading comprehension. You have also learned about the importance of active participation in lessons, and about how songs and rhymes are useful strategies to promote engagement.

You have learned the importance of effective questioning and appreciate the difference between open and closed questions, and when to apply them in literacy activities. Activity 3.9 has given you the opportunity to share your learning so far.

In the next section you will learn more about specific methods for reading and how children require a range of learning activities to support them in learning to read, including the role and importance of their home language which you began to think about earlier in Section 1.