Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 20 February 2026, 2:46 AM

Section 4: Methods for teaching reading

Introduction

In this section you will:

- explore methods for teaching early reading

- talk about and create tasks for children using different reading methods

- find that the methods can be combined and that one method may work better for some children than for others.

In this section you are going to look in detail at three methods for teaching reading and writing. The assumption is that this teaching will take place in the home language and in a print-rich environment, and will involve active learning approaches in order to help children become successful and confident readers.

No single method discussed below is the ‘right’ one. People learn to read in different ways, so one method may work with one child but not with another. If the method you are using is not working with a particular child, try another. In most of your teaching you will need to draw on all the methods in order to give your children the best possible chance to become independent readers.

The most effective teachers of reading, read themselves and talk about what they are reading with enthusiasm. Children get to see for themselves the enjoyment that reading can bring.

Three different methods

Method 1: Sounds, letters and syllables

The phonics method is based on the relationship between individual letters and sounds. Children learn to match letters and sounds, such as ‘c–a–t, cat’ (English) or ‘u–b–a–b–a, ubaba’ (‘father’ in isiZulu). This method is sometimes called ‘the bottom-up-approach’ because it starts with small units and builds towards a bigger picture of reading. It involves children becoming aware of the sounds that letters or pairs of letters make (phonics) and appreciating how these fit together to make sounds within words (phonemic awareness).

This method is important because it enables young children to ‘sound out’ written words that they don’t recognise – even if they don’t understand the meaning of the word. As a teacher you need to know which sounds are represented by the letters in the language you are teaching. These combinations are not the same in all languages. The phonics method requires a child to learn what sounds are represented by individual letters (such as ‘a’ and ‘b’) and combinations of letters (such as ‘th’ or ‘ngq’) in order to read words. Teachers usually begin by teaching single sounds and simple words.

This approach can be useful – and fun – when it is embedded in rhyming. Hearing and predicting rhyming words and syllables is a strong predictor of reading ability.

For instance, if a child sees that certain words sound similar and have similar spellings, she or he does not have to sound each one out:

sad, mad, bad, glad dad, had

end, lend, send, spend, friend

bona, lona, zona, wona (isiZulu)

Groups of words like this are called ‘word families’. Once the children have discovered a word family, you can write it on chart paper and put it on the wall. As time goes on, you can add to the word families on your wall.

Many African languages have long words that are made up from syllables, such as ‘Siyahamba’ – some can be almost like sentences. Children can learn to clap out the syllables of any language to help them distinguish the individual sounds and hear how the word is put together. Words of many syllables often occur in African languages. Children can learn to recognise and read syllables, and then put them together to make words.

Word families and words with repeated sounds and syllables are often found in songs, chants, rhymes and riddles familiar to children. The rhythms and up-and-down tones in songs and chants can help children to remember words, and to read them more easily when they are written down.

Now read Case Study 4.1 and answer the questions that follow in Activity 4.1.

Case Study 4.1: Mrs Mogale’s English class

Mrs Mogale is teaching Grade 1 in a school in the urban township of Soweto. English has been chosen as the medium instruction because the class is made up of children from many different home language groups. Most of the children have some familiarity with English from advertising boards, packaging and television. However, it is still an additional language to most of them.

Mrs Mogale teaches them a rhyme. She read the poem aloud once and then asked two children to come to the front and act the parts. Once the children were familiar with the rhythm of the rhyme, she writes it on the board:

A fat cat sat on the mat.

The fat cat saw a rat.

The fat cat jumped for the rat.

The rat ran away.

She uses the letters, sounds and syllables approach to help them read the first few words.

Pointing to the ‘c’, she asks what sound it makes. Working with one child who raises their hand, she asks them to sound out the rest of the word: ‘C–a–t, cat’. Then she moves on to the next word, asking one child to sound it out and say it: ‘F–a–t, fat’. She then asks if anyone can tell her what the next word says. A child volunteers: ‘Sat’. She then points to ‘mat’ and ‘rat’, and different children read the words. She asks the class what is the same about these words, writing them in a column on the board, one under the other. Children respond that they all end with ‘–at’.

She points to the word ‘saw’ and helps them to sound it out (‘s–aw’), and asks someone to mime its meaning. She points to the word ‘jumped’ and claps its sounds (‘j–u–m–p–ed’), and asks someone to mime its meaning.

Mrs Mogale then reads the rhyme with the whole class, in chorus. They do this a few times. Now she asks two children to dramatise the rhyme while a volunteer recites it. One plays the part of the cat, the other the rat. In this way the able readers get the chance to read it on their own. She allows several pairs of children to do this.

Mrs Mogale has placed letter cards in packets. Some of the letters are single letters (‘b’, ‘c’, ‘f’, ‘h’, ‘m’, ‘p’, ‘r’, ‘s’), and one card has ‘at’ on it. She asks the children to work in pairs. They take it in turns to draw out a letter and put it in front of ‘at’. The person drawing out the letter reads the word and then puts the letter back. The other partner has a turn. When they have been playing this game for 5 minutes, she lets one pair show the class how they do it.

After the lesson, she makes a wall chart for the word family of ‘at’.

Activity 4.1: Thinking about using the letters and sounds approach

Having read Case Study 4.1, talk to a colleague or a friend about the following questions. Write your ideas in your study notebook.

- Why did Mrs Mogale use the letters, sounds and syllables approach to help her class to read the rhyme?

- How did she use the similarities between some of the word-sounds to help the children sound out the word more quickly?

- Are there similar word families in your language?

- Could you use this idea in your class?

- Did the children in Mrs Mogale’s class learn with bodies as well as minds? How do you think this helped them?

- How did Mrs Mogale make her classroom more print-rich during this lesson?

Plan a lesson like Mrs Mogale’s and try it out in your class, or with a group of neighbours’ children, colleagues or friends.

Phonemic awareness

In Case Study 4.1 Mrs Mogale helped the children in her class to decode the words in the rhyme by sounding out the letters – ‘c–a–t’, ‘f–a–t’, and so on. She also helped them to understand the meaning behind the rhyme by asking them to dramatise it. The activity that she gave them helped the children to hear the rhyming sound ‘at’ in all the words in that family.

In all of these activities she is helping the children to understand that words are made up of basic speech sounds, and to play with these sounds. This is called ‘phonemic awareness’. When children can hear and understand these sounds they know when spoken words rhyme, and they know when words begin or end with the same sound. For example, they may learn ‘away’, ‘play’, ‘stay’ and ‘stray’ – and be able to recognise ‘–ay’. Once they are familiar with initial strings such as ‘st’, ‘str’ or ‘pl’, they can begin to put them together and decode new words.

The following video, which was created by World Vision International (2017b), looks at phonemic awareness:

Phonemic awareness is very important for learning to read, but it is not enough. Children also have to recognise the letters of the alphabet (alphabetic knowledge), and the sounds that those letters represent (phonics). Mrs Mogale gave the children opportunities to recognise the letters and sounds by giving them letters to make new words ending with ‘–at’. By doing this, the children understood the relationship between spoken sounds and the letters of written language. This helps children to read and write words.

So phonemic awareness, alphabet knowledge and phonetic knowledge (knowledge of individual sounds) are all necessary for children to become literate – but they are not sufficient. The main goal is reading with understanding. Other methods such as ‘look and say’ and ‘learning experience’ are ways of helping children to make meaning of words.

Something to think about: Think of any chanting rhymes in your language that could help develop awareness of rhymes and letter strings. How could you use these in your class?

Method 2: Look-and-say

The look-and-say method of teaching reading links whole words with their meanings without breaking them down into sounds first.

The meaning of the word and how it can be used in different contexts is very important. Children need to remember the shape and look of the word so that they recognise it when they see it again – in other words, it relies on a child’s visual memory.

If the teacher only uses this method, the child may become lost if they do not recognise the words. Because of this, effective teachers combine the phonics method and the look-and say method when teaching reading.

The look-and-say method is very useful for the many words whose spellings do not match their sounds, such as ‘the’, ‘said’ or ‘when’ in English. When you are teaching a language that has a more regular sound-symbol correspondence, it is easier to match letters to sounds. Sounds and letters in most African languages are linked in a more regular way, which makes it easier for children to learn to read using phonics.

Read Case Study 4.2 and answer the questions that follow in Activity 4.2.

Case Study 4.2: Mrs Mapuru uses the look-and-say method

Mrs Mapuru is teaching Grade 2 in a school situated in a rural area. Her children have had more than a year learning to read in their mother tongue and are now learning English and building reading skills in English.

She has collected pictures of fruits and pasted them on to cards. Each card has the English name of the fruit under the picture. She has also made about 15 sets of four cards, each of which has only the name of a fruit with no picture.

She holds the picture cards up one by one and makes sure that the children know the names of the different fruits: banana, apple, pear, peach, mango, etc. She then shuffles the cards and holds them up in a different order, letting the children chorus the names of the fruits. She repeats the name and spells out the words: ‘Mango, m–a–n–g–o, mango.’ She does this a few times, encouraging the class to say it with her.

Mrs Mapuru then uses a set of cards without pictures and lets children put up their hands and try to read the words. She does not break down the names of the fruits into sounds; children have to read words as a whole. She goes back to the picture words once or twice and then tries the cards without pictures again. Then she sticks the cards with pictures and words on her English word wall.

She divides the class into pairs. Each pair has a set of four cards. They try to read them, turning them over one by one and reading them to each other. They try to read them without looking at the word wall first, but if they are stuck they can get help by looking at the wall. Pairs can exchange their sets of cards with another pair once they can read them well without looking at the word wall.

After this, Mrs Mapuru can ask the children about different kinds of fruits: ‘What other kinds of fruits do you know?’, ‘What colour is a banana?’, ‘How do you eat a banana, do you eat it with the cover on or do you need to peel it?’, and so on. She can let them talk in pairs about the fruits that they know and the ones they like the best. Then they can report back to the class about their favourite fruits, using a sentence she gives them: ‘I like to eat (bananas).’ As they say their sentence, they hold up the word.

Later, she reads a story about fruit to the children and builds a lesson around it. You can read about that in Section 5.

Activity 4.2: Thinking about ‘look-and-say’

Having read Case Study 4.2, talk to a colleague or a friend about the following questions. If you have no partner, write your ideas in your study notebook.

- How is the teacher using the look-and-say method?

- How does Mrs Mapuru use this method to help the children to read words describing fruit?

- How does she make sure that each child is actively involved in the lesson?

- How does she make sure that the children understand the meaning of the words they read?

- How do you think Mrs Mapuru made her picture cards? Where could she have found pictures to cut out? Could she or her children have drawn the pictures of fruit? Can you think of other ways she could have collected the pictures?

- Where could Mrs Mapuru have found cardboard to stick the pictures onto? Are there boxes in your area that you can collect and cut up for flash cards and charts?

- What other kinds of objects could you use to teach a lesson similar to Mrs Mapuru’s?

In English, there are many small but very common and important words, such as ‘the’, ‘of’, ‘for’, ‘to’, ‘said’, ‘when’, ‘is’, ‘are’, ‘was’ and ‘were’.

Which of these words can easily be sounded out? You will see that only a few of them can. It is also impossible to draw pictures of these words. Most of these are therefore best learned in the context of a poem or a story as part of a look-and-say approach. You need to teach them to your children using the look-and-say method and have them written in a special place on your word wall. This will help the children to ‘write’ them in their visual memories, where they won’t be forgotten.

Activity 4.3: Look-and-say words

Think of ‘look-and-say’ words in English that would be suitable for your word wall. Make a chart for your word wall if your children are learning English.

Think about the children’s home language. Does it have common words that are difficult to sound out, which children need to know by sight? Make a list of them on a chart for your word wall.

Optional activity: You could help the children you teach by becoming familiar with the letters that make up words, asking them to look for words within a word. How many words can you make from ‘mango’, for example? Can you think of some word in English or in your home language that you could use?

Method 3: Language experience approach

The language experience approach focuses on children’s experience and enables them to read about their own lives, in their own words. Skills for reading are based on their knowledge of the language they are using and on their home and community backgrounds, the people they know and the experiences they have. Children work with whole words and sentences rather than letters and parts of words. It allows children to speak before they read and write.

The approach consists of the following four steps:

- Experience: Children do many things at home and at school, usually with other people.

- Description: Children talk about what has happened to them, to each other and/or to the teacher or the class.

- Transcription: Children write about the experiences they have described. Before their writing skills have developed, they can draw or try out writing, or the teacher can write down what they want to say.

- Reading: The children read what they have written to the whole class or to a part of the class.

Read Case Study 4.3 and answer the questions which follow.

Case Study 4.3: Mrs Tekiso uses the language experience approach

Mrs Tekiso is teaching Grade 1 in a school situated in a rural area. The language spoken by her children is Setswana. It is the second half of the school year.

One morning, in the ‘News’ slot of the timetable, Mrs Tekiso asks her children to talk about what they did the day before. Each child is given a chance to talk. She then asks them to draw a picture of what they have told the class and to write a sentence under the picture.

When they have finished, each child shows their picture to their partner and reads the sentence they have written. Then two pairs exchange pictures. Each pair ‘reads’ the two pictures in front of them and the words written on the two pages.

Mrs Tekiso then asks the children to return the pictures to their owners. Each child comes to the front, shows their picture and ‘reads’ their pictures and sentences to the class. The class applauds each child’s work. Without criticising any child’s picture or writing, Mrs Tekiso writes correctly, on the board, the key words that the children have written. She and the class read the words on the board together.

After the lesson, Mrs Tekiso pins the drawings up on the classroom wall. She also puts some of the new words they have used on the word wall.

Activity 4.4: Thinking about the language experience approach

Having read Case Study 4.3, talk to a colleague or a friend about the following questions. If you have no partner, write your ideas in your study notebook.

- What has this case study shown you about the language experience approach? How does Mrs Tekiso use this method to help the children to read?

- How does the approach ensure that each child is actively involved in the lesson?

- How does the approach ensure that they understand and are interested in what they read?

- How else could Mrs Tekiso enable her children to write down their story?

- Can you think of how else a storybook could be used as a starting point for a lesson using the language experience approach to reading?

Discussion

Here are some ideas we have about ways to help young children to read about their own experiences.

The language experience approach ensures that each child is actively involved by letting them write and read about their own experience. This also means that they are interested in what they are doing and understand what they have written and read.

Instead of letting them try to write their own words, Mrs Tekiso could have gone round the class asking them which word they wanted to write. She could then have written it herself at the bottom of the page. The children would then have read the word to their partner and to the whole class.

If Mrs Tekiso had wanted to use a storybook in the language experience approach, she could have read the story to the children and asked them what they thought of it, or whether they had ever experienced something similar. For example:

- If the story is about fruit (for example, Punishment), she can ask the children about their favourite fruit. They could then draw the fruit and write its name. Alternatively, she could write the fruit’s name for them. They would then have a chance to read the word.

- If the story is about somebody who made a mistake and learned a lesson (such as Chicken and Millipede), children can talk about a time when they made a mistake and learned a lesson. If the children are a bit older, they can write a sentence or two about what happened to them and read it to the class.

How would you use the language experience approach? You will have a chance to think about this in Activity 4.5.

Activity 4.5: Using the language experience approach

Plan a lesson like Mrs Tekiso’s in your study notebook. If you have the chance, try it out in your class, or with a group of neighbours’ children, colleagues or friends. You might want to use one of the approaches in the discussion section of Activity 4.4 instead of following Mrs Tekiso’s plan exactly.

Bringing it all together

An effective teacher will draw on all three of these methods to help children learn to read. They usually do these by finding a story that:

- will appeal to the children

- has some repeated words and rhyming words

- has words where they can use pictures (the look-and-say approach)

- has a picture of what is happening in the story (the language experience approach).

Activity 4.6: Reflecting on your learning

Spend some time browsing the ASb website and find some stories that are suitable for supporting young readers. As you read the stories, think about which approach to reading you could use: letters and sounds, look-and-say, or the language experience approach. Do some stories lend themselves more to a particular approach? Share your ideas with a colleague.

This section of Teaching early reading in Africa has introduced you to three methods of teaching reading and given you a chance to try them out. You are encouraged not to restrict yourself to any one of these methods, but rather to combine them as required to support young readers. (In Section 5 you will see an example of how to use the methods together.)

It is important to remember that different children may respond better to one method than another:

- Some may have a better visual memory than others.

- Some may like analysing words into separate sounds and others may not.

- Some may like to be given more specific instructions than others; they may not like the freedom that the language experience approach offers.

If certain children are struggling to learn to read, you might find that concentrating on one particular method might help them overcome their difficulties.

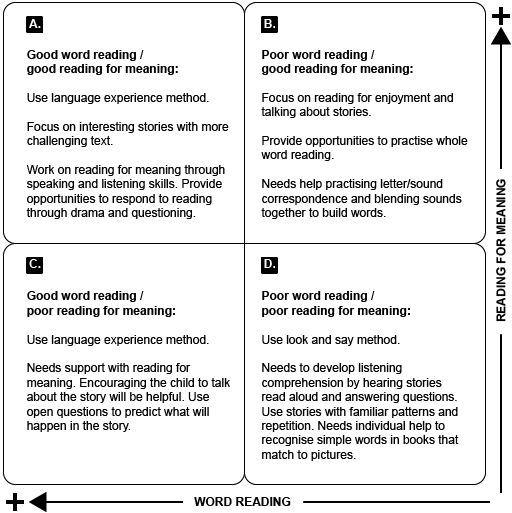

Figure 4.2 shows that to be a good reader, you need to have good word reading and good reading for meaning. Some children may understand more easily than others what they read, but may have difficulty sounding out words and working out what they are. Others may be able to work out and recognise words, but have difficulty in understanding what they have read.

You will spend more time on Figure 4.2 in Activities 4.7 and 4.8.

Activity 4.7: How to use the figure

Talk about Figure 4.2 with a colleague or a friend. What does it tell you about how to help children with different strengths and weaknesses?

Discussion

The first quadrant (in the top left of the diagram) tells you about children who have good comprehension and good word recognition skills. These children do not need extra help, but you should give them some more difficult and challenging stories so that they can improve still further.

The second quadrant (in the top right of the diagram) tells you about children who have good comprehension and poor word-recognition skills. They understand quite easily but battle to work out what certain words say. You can support them by emphasising reading for pleasure by choosing stories that will motivate them. You can also provide extra help, by helping them to recognise the different sounds in a word.

The third quadrant (in the bottom left of the diagram) tells you about children who have poor comprehension but good word recognition skills. They can tell you what the words are but don’t know what the words and sentences mean. This can sometimes indicate other developmental problems which a teacher should monitor. They should benefit from writing and reading about their own lives and experiences. This will mean that what they read has meaning to them.

The fourth quadrant (in the bottom right of the diagram) tells you about children who have poor comprehension and poor word recognition skills. They are battling with all aspects of reading. They need texts that will motivate and enthuse them, and are related to their everyday lives. They will benefit from a lot of extra work with the look-and-say method.

Activity 4.8: Which method of word recognition and good comprehension should you use?

Moving forward

In this section, you have learned about the different methods for teaching reading and you have learned that different methods suit different children. You have learned the importance of matching reading activities to the children’s experiences, so that literacy learning is meaningful and purposeful. You have read case studies to reflect on the approaches that different teachers take when teaching reading and you have considered which best match your own approach. You have learned that a child who is a good reader needs skills in word recognition and comprehension. You have considered that some children are stronger in one of these skills than the other and you have learned more about how you can support different readers in your class.

In the next section you will be learning more about how stories and storybooks can support children’s literacy learning. You will also spend time thinking more about how you can increase the time spent on speaking and listening activities within the classroom.