Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 7 February 2026, 12:52 PM

Managing and understanding yourself

1. Introduction

This section includes:

- Introductory text

- An information box on “What is an emotion?”

- 1 video.

You should allow yourself 20 minutes to complete this section.

This part of Fit for Law gives you the opportunity to think about how you exercise your judgement, know your limitations, take on responsibility, deal with stress and reflect on your work. Its fundamental premise is that acknowledging and regulating emotion and factoring emotion into your work will enhance your legal practice and your wellbeing, both of which are important to ensure a healthy legal profession. This video shows a variety of legal professionals giving their views on why these issues are important.

Why you need to be Fit for Law

Transcript

You may find some of the sections cover areas of emotional competence you already have strengths in, others might cover areas you find more challenging. When you see a section you are good at, it is worth noting this down as a key strength. When you find a section you feel you need to work on, you should note this as a developing area and try to identify some short-term goals to help you improve on this. In other words, create your own personal development plan.

You could do this using a notepad and pen, or a word document, or even a notes function on your phone or tablet. The important thing is to ensure it is kept somewhere safe and secure where you can read it back at a later date. For example, if you are struggling with confidence, you can look over your key strengths to get a better perspective on your abilities. When you are feeling able to improve, you can work towards improving your developing areas to upskill yourself (perhaps using your Continuous Professional Development allowance).

What will I gain from this topic?

It is vital for legal professionals to demonstrate emotional competence. In other words, regulate their responses to emotion in an appropriate and psychologically healthy manner. Anyone in legal practice is constantly (knowingly or unknowingly) dealing with range of emotions as they interact with clients, colleagues and others, juggle a variety of tasks and demands and seek to balance the pressures (and pleasures) of work with family, leisure and other commitments. Understanding this and learning how to manage emotions in themselves and others will enhance their performance at work and also their professional resilience.

Legal professionals who use their emotional competence effectively will have the professional resilience needed to deal with a challenging and demanding working environment. Understanding the role of stress and reflecting on their approach to practice will assist them in developing emotionally and psychologically healthy ways of working.

In the long term, trying to ignore these elements of legal practice is unlikely to be an effective strategy. If a legal professional struggles to regulate their emotions effectively and does not develop appropriate levels of professional resilience, this can significantly impact both on the quality of their workplace performance and their personal wellbeing (as well as that of those around them). In the longer term, it can also contribute to psychological issues such as burnout, or vicarious (secondary) trauma (experiencing trauma symptoms after engagement with traumatised clients, or after encountering accounts of trauma).

"…So when I started doing nasty kind of child sex cases and stuff, and I have a friend who’s a police officer, a friend who works in social services, they had counselling, support, just viewing horrible images; whereas for barristers, criminal defence barristers you have no extra training."

"I have to be able to go from one office or one room 20 minutes ago talking about a completely acrimonious litigation matter to then be sensitive to deal with someone whose wife has just died two days ago. You know, you have to. And when you’re doing that for eight hours a day, it’s impossible to switch off. You’ve had the whole emotional circle going on in your head..."

What is an emotion?

This may seem like an obvious first question for a course involving emotional competence, but in fact there is a vast amount of scientific and philosophical debate about what emotions actually are, with many commentators tracing the debate's origins back to Plato and Aristotle in Ancient Greece. A simple starting point is to define an emotion as “…a particular, conscious event, high in intensity but short-lived and easily labelled and recalled” (Bornstein and Wiener, 2010: 1).

For example, the experience of relief when a deadline is met or disappointment when a claim goes badly. In Section 2, the role of emotion will be explored in more detail. In the box below, read through the definition of each emotion and the example of how that emotion might feel. Notice how these descriptions show the way the individual and their environment interact to give rise to a particular emotion. The emotion is influenced by the individual, the environment and the context.

This idea of the interaction between individuals and their environment giving rise to emotions reinforces how important it is not to simply change an individual’s response or emotion, as these do not occur in a vacuum. Instead, it is important to consider the environment and context, such as the legal workplace, that give rise to particular emotions.

Please click on the faces below to see examples and definitions of common emotions

It would be useful to pause here and spend a moment thinking about which of the emotions you have experienced during your work in the last two weeks stick in your mind. Firstly, think about what characteristics or circumstances of work gave rise to these emotions? Secondly, think about how you dealt with them and were these strategies successful?

I’m not stressed or feeling burned out, is this topic relevant to me?

Emotional competence and professional resilience are fundamental parts of legal practice for everyone. Even those who are able to regulate their emotional responses very well overall may find that there are some situations or issues that arise where they are uncertain or worried about how to respond. Even people who enjoy working under pressure can find stress beginning to impact on their work and wellbeing. Those who are naturally reflective may find that this is eroded as the pressure to rack-up chargeable hours becomes a key focus, similarly those who feel they thrive on pressure may reach a tipping point where they feel overwhelmed by deadlines, paperwork and the demands of cases...

"… and it took that almost crisis with me where I burned myself out where I thought something has to change significant in my life"

"…you know, lawyers, they’re not all tough cookies, you don’t have to be a tough cookie."

This topic will cover common situations and issues that arise within all areas of legal practice, identify some of the challenges and opportunities and provide you with useful, evidence-based tactics and suggestions for dealing with them. Its focus is on up-skilling people to work in emotionally and psychologically healthy ways which will benefit them personally but also those around them and the wider legal working environment.

2. Exercising your judgement

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- An information box on “Emotions and decision-making”

- 1 activity on “Identifying the role of emotions in judgement”.

You should allow yourself 30 minutes to complete this section.

As a legal professional, you are likely to have to exercise judgement in a wide range of situations, from selecting which sub-section is most likely to apply in a dispute, to deciding what to wear for an important meeting, to considering how to word a letter of advice to a client. Exercising judgement is also needed in a range of other legal workplace scenarios: From deciding whether to advise a client to issue a claim, to considering whether to run something past a more senior member of staff, to debating when to take your annual leave.

The commonly held view is that because legal practitioners must exercise their judgement in a reasoned and objective way (“thinking like a lawyer”), they must ignore and disregard any forms of emotion as irrational and misleading. This is largely based on a view of emotions as primitive evolutionary throwbacks (sometimes referred to as a “basic emotions” view). This is a popular view in Western societies which effectively views your thinking processes as a form of hierarchy, with emotions at the bottom, needing to be firmly suppressed by the cognitive functions of reason and rationality.

In fact, in recent decades, research in neuroscience and psychology has demonstrated that the relationship between emotions and cognition is much more complex than this, with the two effectively being intertwined (there are several different theories regarding this, but a key one is known as “appraisal theory”). What this means is that we cannot separate out and ignore our emotions as they are an integral part of the way we process information, react to situations and make decisions and judgements. This applies in our working life as well as our personal life.

Neuroscientist, Antonio Damasio (2006) gave a clear illustration of this when he discussed the case of his patient, Elliot, who had brain lesions which left his intellect intact whilst seemingly destroying his capacity to experience complex emotions.

Emotions and decision-making

Activity 1: Identifying the role of emotions in judgement

Part 1

Read the following brief scenario and consider how emotion may play a role within it. You may find it useful to look back at the key emotions interactive to remind yourself of some of the range of emotions that could be present. If you wish to, you can note down your thoughts and save them using the text box below. When you are ready click on “reveal comment” to see the authors’ ideas:

You are one of a team of solicitors preparing for a meeting with a large corporate client where you will advise it on a potential claim against a competitor. The client is keen to add several new particulars to your draft claim form. You feel these are fairly minor amendments and the team quickly agrees to them. However, when about move on, you suddenly have a fleeting feeling that something is not quite right. Although you only pause very briefly, the remainder of the team pick up on this and seem more attentive and serious. A trainee solicitor raises a point about a possible inconsistency in the particulars, which has been discussed previously, but which now leads to others in the team raising similar concerns. You encourage this detailed analysis and it becomes clear that the amendments could potentially have a significant impact on the strength of the claim.

Comment

You may have identified a range of ways in which emotion is involved (supporting our premise that it is part of every situation!). In particular, by pausing before moving on you had identified that you were experiencing a specific emotion and acted on it. You recognised that something was not right. You then discerned that the change in the attitude of the team was due to a potential issue, thus understanding and interpreting the emotion that was present in other team members.

Your pause, and the change in attitude, then led to both you and your team focusing on the issue in a more analytical and searching way – using the emotion you felt to influence and assist your thought processes. You did not ignore the emotion and move on, instead you gave your team time to uncover the issue by integrating emotion into, and regulating, your response in a way which may well prove beneficial to both the team and your client.

In scientific terms, this sort of emotional information is called ‘integral’ emotion. It is relevant information and is integral to the task at hand. It is important because, where it is relevant to the task or situation, there is evidence that attending to our emotions can improve our decision-making and reasoning (Blanchette and Richards, 2010).

In contrast, there are ‘incidental’ emotions which refers to emotions that are not relevant for the task or decision (for example, you are feeling anxious about a result from a medical test) and that can affect your approach to work. In such cases, this emotion is incidental to any tasks at hand, and acting on this emotional information would not improve judgement and decision-making at work and may degrade it.

It is equally important to identify and understand this emotion as irrelevant to the work task to assist you in not allowing it to impact on your judgement and decision-making.

Part 2

Think of a common workplace scenario that has arisen in your own legal practice during the last two weeks. For example, a client interview, a conference, a team meeting, a supervision or appraisal.

Comment

Depending on the scenario you chose, you may have experienced a range of emotions from boredom, frustration and misery to enjoyment, happiness and pleasure. The likelihood is, the more involved you were in the situation, the more intense your emotionsl would have been. The emotions of the other person or persons involved may well have influenced your own emotions too. For example, if someone was feeling very excited about a project you may have picked up on this and begun to feel more positive about it as well. This is sometimes referred to as “emotional contagion” or “mirroring” (Hatfield et al, 2011).

If you found it easy to identify which emotions were present, that’s great (but it’s still worth checking out the next section to make sure you did get the full picture). If you found it difficult, or weren’t sure, that’s not surprising. It is extremely rare for this topic to form part of legal education and training despite its importance in legal practice.

The rest of this section will focus on how to identify and understand the emotions you experience in such scenarios and explore how to incorporate these into your judgements and regulate them appropriately.

2.1 Identifying and understanding different emotions

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- An information box on “Digging down to up-skill”

- 2 videos

- 1 activity on “Using emotions productively in legal work”.

As this diagram demonstrates, it is not always easy to identify which emotion you are experiencing. You may think you are feeling one particular emotion, but there may actually be a number of different emotions contributing to your experience. If your reaction to an emotion is to “think like a lawyer” and try to ignore or rationalise it, the likelihood is you will only identify what’s on the surface. This can lead to you misunderstanding what’s happening and missing valuable information and cues, as demonstrated by the following examples.

Digging down to up-skill

Examples adapted from Silver (2004).

You find one elderly client particularly difficult to deal with, often getting annoyed when they seem to talk around issues without getting to the point. You initially feel that the client is being deliberately difficult and obstructive However, when you think about why this is so annoying, you realise it reminds you of an elderly relative who you feel guilty about avoiding visiting. You also realise you are very anxious about having enough time to submit an important document on another case and that this has affected your response.

You look forward to seeing one of your clients who you feel has a similar outlook on life and who you get on with extremely well. You are particularly sympathetic to your client’s case and feel strongly that they are in need of your help. However, when you begin to add up the time you have spent on this case you realise that you are attracted to the client and that these feelings (sometimes known as “counter-transference”) are influencing your perception of their case. There is also an element of pride, as you are keen to demonstrate your abilities to the client and impress them.

This video of occupational psychologist, Dr Rajvinder Samra, explains more about how identifying and understanding emotions can impact on your work.

Emotions in the workplace

Transcript

This video gives examples of how one legal professional has learnt to acknowledge her emotions.

Acknowledging emotions

Transcript

Activity 2: Using emotions productively in legal work

Identify any times when you have made a work decision based (at least in part) on your emotions?

2.1.1 Some practical tips

This section includes:

- Practical tips

- Useful web links.

You should allow yourself 10 minutes to complete this section.

“… but the first step for me is awareness and knowing what feelings and emotions are.”

Some practical ways you can develop your skills in identifying different emotions include:

| Building in a pause. If you think you are experiencing a particular emotion, don’t push it to one side. Instead, spend a moment to try and work out why you are experiencing it and what might lie underneath it. This does get easier with practice! | |

| Reflecting after the event. If you experience a strong emotional reaction don’t just forget about it. Make a mental (or even written) note of it and set aside a few moments in the following 24 hours to think about what influenced it. | |

| Developing your terminology. Spend some time learning more about different emotions, so you have the vocabulary to identify what you are experiencing more easily. A good starting point is the Greater Good Magazine published by the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley which contains a lot of information on different emotions (and other related topics, including a quiz on emotional intelligence. | |

| Getting input from others. Talk to people who know you well, such as family, friends or even a close colleague. Often they will have a different insight into which emotions you are experiencing and why. | |

| Sleep on your feelings: Sleep helps us learn and process our learning. If you are unsure what you are feeling, come back to the situation after a day (and a night’s sleep!) and see if that helps you process what emotions you might have experienced. |

It may be that becoming more aware of your feelings makes you realise that you have been suppressing some uncomfortable, even distressing, emotions. This might particularly be the case if, for example, you are involved in a difficult or harrowing matter (which can lead to your experiencing vicarious/secondary trauma) or your work-life balance has been slipping.

"… I was in my 20s, you know, and dealing with rape, sexual abuse of children, quite a lot of unsavoury topics, and didn’t know anything about anything, just suddenly had to do court work. I was so busy trying to sort out the court procedure and what form do you fill out and everything, and the actual issues that I was dealing with, no-one ever to this day ever spoke to me about them, you know. I just heard it from the client or read statements and then had to go into court and speak about it."

"What I would say though is that having been aware of and worked on various corporate deals and transactions, you can get a situation whereby the deal has to be done no matter what. And you do get people staying until two, three o’clock in the morning, completely nothing else around them matters, all they’re working on is their work. And that’s when I think potentially there’s a real risk of stuff like mental health issues or people who aren’t quite coping with that kind of pressure going unnoticed."

Often, identifying and reflecting on these can make them more manageable and easier to regulate. It may also make you aware that they are providing valuable indications that you need to reassess parts of your workload and/or your approach to it. However, if you feel like these emotions are becoming unbearable (sometimes called distress intolerance) there is detailed guidance to help you work through this.

2.2 Incorporating and regulating different emotions

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- Checklist for “Utilising emotions”

- 2 videos.

You should allow yourself 20 minutes to complete this section.

Once you can identify and understand the emotions you are experiencing, the next step is to utilise these skills in the way you work. A common misconception about emotions amongst legal practitioners is that, if you admit to having emotions, they will all come flooding out (a sort of variation on the floodgates argument often found in tort!). This isn’t the case. Your emotions are there whether you acknowledge them or not, but spending more time identifying and understanding them, and their impact on your work, will actually help you to regulate them more appropriately. This video gives some examples of how individual legal professionals have found emotional competence helpful to them.

Using emotions appropriately

Transcript

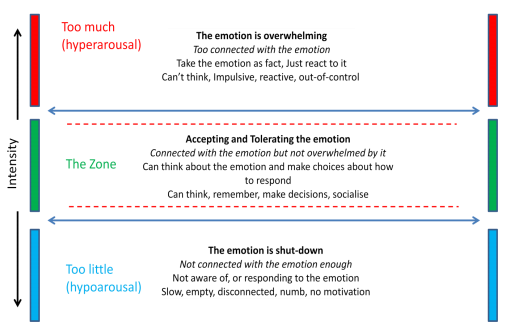

By regulating our emotional responses, we mean managing them in a way which ensures they remain within an appropriate zone or window of tolerance without becoming too intense and over-whelming (known as dyscontrol or hyperarousal), but also without seeking to suppress or ignore them (known as dissociation or hypoarousal). It is the latter that the culture of legal practice sometimes seems to promote.

Take five minutes to look back at the example you selected in Activity 1. You may be able to think of ways in which you could have regulated your emotional responses in the scenario to handle it more effectively or healthily. For example, if you had thought about a client interview and identified that you had found it difficult because the client had seemed uncomfortable and unable to explain their position clearly, you might find it useful to think about what emotional cues you presented to them in your speech and body language and whether you had made any effort to empathise with their situation.

The following diagram provides a useful checklist for considering how to incorporate and regulate emotions, but you may wish to adapt it to suit your own legal workplace and ways of practicing.

Utilising emotions

- WHO? Who is involved in this situation and what are everyone’s (particularly your own) emotional responses?

- WHY? Why am I having this emotional response?

- WHAT? What could this emotional response tell me about this situation and my reaction?

- HOW? Are there any ways I should modify my behaviour or approach based on this emotional response? What can I do next time to avoid having a negative response?

If you run through this checklist regularly, you may begin to see that there are key patterns or themes that emerge. For example, some legal practitioners report that they find time management challenging. This can lead to feelings of stress and anxiety, which in turn may regularly influence the emotions they experience in a range of different workplace situations (the type of “incidental emotion” referred to above).

If you do identify any key themes or patterns, then there is a need to address these to enable you to regulate your emotional responses more effectively and focus on working with your valuable, integral emotions. In other words, you need to explore the root cause of your reaction. For example, in the case of time management, it may be that there is a need to discuss reallocating some of your work load, or that you need further administrative assistance, or that you need to take other practical steps (such as using a more effective reminder system to help you prioritise) to alleviate the issue and avoid it skewing your emotions in an unhelpful way.

Alongside considering your emotional responses, it is also valid (in fact, important) to consider your own emotional wellbeing, and that of others involved in the situation. If you are finding yourself or those around you increasingly pushed out of the zone of tolerance, this is something you need to address. This will be discussed further in section 4.

This video of occupational psychologist, Dr Rajvinder Samra,explains more about incorporating and regulating emotions in the workplace.

Regulating emotions in the workplace

Transcript

3. Knowing your limitations

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- A “Questions to ask yourself” checklist

- 1 video.

You should allow yourself 20 minutes to complete this section.

One of the many useful functions different emotions can perform is acting as a form of “early warning signal” (Zautra, 2006, p.9). Often this “signal” will take a similar form each time you experience it. For example, you could get irritable, angry, argumentative, tired, feel ill or feel less caring towards, or interested in, others.

This type of "signal" is particularly relevant in legal practice when you may be given tasks or expected to perform in ways you find uncomfortable or challenging. For example, as a trainee solicitor or chartered legal executive, or pupil at the Bar, you may be faced with a client demanding immediate advice on a topic you have not previously researched in detail. In many legal roles, you may be expected to perform managerial tasks which your training did not equip you for (such as supervising and/or leading others).

Listening to your emotional response and understanding the signal it is providing can help you to think about whether or not you are competent to take on a task or role. If you aren’t competent, the consequences can be significant for both you and others involved.

You may also want to think about the "early warning signals" of those around you, for example, your manager, supervisor, support staff or other colleagues. If you can identify these "signals" it will help you understand when that individual is under stress, help you avoid taking their reaction too personally, and also encourage you to be aware of when that person may need some form of additional help and support.

To be able to put your emotional response in context, you need to think about whether you do have the competence to take on what is being asked of you.

The following video discusses the importance of acknowledging and understanding your limitations.

Acknowledging your limitations

Transcript

[LAUGHS]

The following diagram provides a useful checklist to help you consider your limitations, but you may wish to adapt it to suit your own legal workplace and ways of practicing.

Questions to ask yourself

You can click on each possible answer to see ways to tackle the issue.

3.1 Communicating about difficult issues

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- 1 video.

You should allow yourself 10 minutes to complete this section.

If you aren’t able to take on a role or task, or cannot agree to something else that is asked of you, for whatever reason, it can have a significant emotional impact. It can lead to feelings of guilt, worry and anxiety, as well as a sense of embarrassment. For example, imagine you are a legal executive in a personal injury department and your manager asks you to undertake a residential conveyance for a client as a personal favour. You may feel anxious that refusing will affect your annual appraisal or promotion prospects or you may feel guilty about “letting down” a colleague. You may even feel that admitting you don’t know your leasehold from your elbow (!) is a sign of weakness.

There is evidence from legal professionals that admitting to issues around mental health and wellbeing, or indicating that these may affect your work, can also lead to a strong sense of stigma and shame or be interpreted as a sign of weakness.

“I think a lot of lawyers won’t want to talk to their line manager or somebody. You know, why would you admit that?... They might see it as a weakness; they may not necessarily understand the problem.”

It is important to identify and understand these emotional responses and to assess whether these are grounded in reality or whether they are being magnified or skewed because admitting issues or limitations is something that you find difficult, or that your legal training has led you to believe it is not something that legal professionals do. When you have had time to reflect on this, it can also be very useful to plan your communication strategy carefully. The following questions (adapted from Holmes, 2015, based on the Giving Voice to Values curriculum) can help with this:

- What factors/approaches have enabled you to communicate issues or limitations in the past?

- Whose interests are affected (and how) by what you are going to say?

- Who are you going to communicate with, how and in what context?

- What is putting you off communicating your issues or limitations?

- How might you reframe the issue so that you feel more likely to act (bearing in mind the factors/approaches that have helped in the past)?

- What might happen if you do not communicate this information?

- How might not communicating affect you and any other parties involved?

- What are the possible responses of the person you are communicating with, and what would the motivation be for these?

- What are the most powerful and persuasive responses you can think of to use?

When you have thought about these questions, take any opportunity you can to practice what you want to say with family, friends or a supportive work colleague. This will give you confidence that you can communicate clearly and also help you to regulate your emotional responses to the situation. This video of Senior Lecturer in Mental Health, Dr Mathijs Lucassen, provides you with some practical tips on regulating your responses.

Regulating your emotional responses

Transcript

Dealing with this type of situation effectively will also help develop your professional resilience as you begin to become more comfortable with communicating in this way and ensuring your needs are acknowledged.

3.2 Dealing with mistakes

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- “Adopting a growth mindset” examples

- 2 videos.

You should allow yourself 20 minutes to complete this section.

"…because you do dwell on stuff, you take stuff with you and you think oh I’m so stupid, my supervisor is going to think I’m an idiot'."

"I’m very much reminded of the first time that I thought I’d made a horrendous mistake many years ago and I went through to the then senior partner and said I’ve made a terrible mistake. What have you done? So I told him and he said show me the file... no you haven’t!' And I found that very comforting..."

For many legal practitioners, a mistake is seen as a type of failure. The sense of letting yourself and/or others down can be difficult to handle. There may also be worries over the practical impact of your mistake (including, in some cases, the potential for disciplinary proceedings and/or negligence claims). This video demonstrates how a number of individual legal professionals' handle mistakes and difficulties.

Coping with mistakes and difficulties

Transcript

The simple reality is that everyone is going to make a mistake every now and then, what is key is how you deal with the situation, and also what you learn from it. This blog post from The Law Society of England and Wales gives useful advice which can be applied to most legal professionals

There may be some sectors of the profession, for example, if you are self-employed, a sole practitioner or a member of the judiciary, where you have limited support from others. If this is the case, you do need to think about whether you can identify anyone to act as a form of (formal or informal) mentor to assist when such issues arise or consider obtaining guidance from your regulatory or professional body perhaps.

In terms of emotional competence, it is important to think about how you regulate your emotional responses to avoid being overwhelmed by negative feelings. Instead of (or after!) panicking, take some time to calm yourself down, process your emotional responses and then focus on how to tackle the issue to develop a solution-oriented approach. Often taking some time to calm down allows you to think about situations more clearly and to identify the correct way of dealing with issues that have arisen. This is likely to involve apologising, speaking to others involved and trying to identify a solution. This video of Senior Lecturer in Mental Health, Dr Mathijs Lucassen, gives some practical tips on handling these issues.

Dealing with your emotional responses

Transcript

In terms of professional resilience, the concept of a “growth mindset” can be valuable in this situation. Dweck (2017) argues there are two forms of mindset (ways of thinking about yourself). The first is a “fixed mindset” which assumes that you have a fixed intelligence, personality and character which you simply have to accept and live with. This leads individuals to constantly to seek to prove themselves – to demonstrate that they are smart, funny, loyal and so on. They may avoid challenges or chose not to put in effort (“what’s the point if things cannot change?”).

The alternative is to adopt a “growth mindset” and view these things as works in progress that can be developed and cultivated through your efforts and the support of others. Dweck argues that “… everyone can change and grow through application and experience” (2017, p. 4). This leads to individuals embracing challenge and putting in effort to improve themselves. This is only a very brief introduction to the theory (and in some situations feeling you have to constantly strive to improve yourself could be very unhealthy). However, the idea of a “growth mindset” can help when tackling mistakes or, as demonstrated by the following video, when managing rejection.

Managing rejection

Transcript

Adopting a growth mindset

Scenario 1

It’s Monday morning and you are about to go to court…

You think – “This will be stressful, but I’ve done my prep”.

You do – Walk into court right on time outwardly appearing very calm.

You feel – Nervous, but also a bit excited (because of the challenge ahead).

Versus

You think – “I’ve been preparing all weekend, but I can’t cope with this, it’s too much for me”.

You do – Get a coffee and wait in the cold some distance away from court.

You feel – Increasingly panicky and down.

Scenario 2

It’s 4pm on Wednesday afternoon and a senior employee asks you to review four boxes of papers for 9am on Thursday…

You think – “I must show I can do this, I don’t want to look like I’m not committed.”

You do – Work until 1.30am and come back into work for 7.30am to finish off.

You feel – Tired and worried that you’ve missed something.

Versus

You think – “I know I can do this, but I need the time to do it properly”.

You do – Speak to the senior employee and negotiate a revised timescale for lunchtime on Thursday, leave the office at 7pm and come back at 8.30am.

You feel – Confident and better rested.

In each of these two scenarios, a fixed and growth mindset approach to the same problem has been outlined. You can see that the fixed mindset response may be about covering up perceived personal flaws or weaknesses and protecting yourself from shame and failure. This is based on the mistaken belief that you cannot improve or grow from the challenge.

The same scenario can give rise to a more productive growth mindset approach in which the stress or challenge can be handled and individuals may develop or grow as a result. The alternative growth mindset response also demonstrates a “reframing” of the problem. This is a powerful technique where we think differently about a problem and engage with it instead of allowing it to block our way.

4. Handling responsibility

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- “Handling responsibility” checklist

- 1 video.

You should allow yourself 15 minutes to complete this section.

Legal practice can sometimes feel like a balancing act between giving your clients the best advice and assistance possible, but also ensuring you are avoiding putting you and/or your employer at any risk of liability if things go wrong. You may also be experiencing pressures relating to chargeable hours and billing targets. Sometimes balancing the conflict from these different roles, responsibilities and pressures can be challenging or stressful.

Additionally, the more responsibility you take on, the more worry this can cause and the more decisions you will have to take. It is important to be able to handle this process in an emotionally and psychologically healthy manner to help you find an appropriate balance and handle your responsibilities well.

“Sometimes because you’re so busy of course you can go around in circles in your behaviour because you don’t really have time to stop and think how you’re reacting to people or situations.”

Section 2 of these resources demonstrated the role of emotion in judgement and decision-making. It is important to acknowledge and utilise this when it comes to taking on and handling responsibility and balancing your obligations. This checklist can help you do this:

Handling responsibility checklist

Be self-aware

Discussion

Take the time to understand what emotions handling responsibility generates and how these impact on you. One useful way to do this is by practising mindful meditation, but there are many others. For example, you could draft your own personal self-help manual based on the strengths and weaknesses you identified when working through these resources

Be conscious of internal conflicts and tensions

Discussion

Identifying then ignoring internal conflicts means that they will continue generate negative emotional responses, including incidental emotions that distract you from the task at hand. There is also the danger that you are disregarding important signals telling you that there is an ethical or moral issue you need to address.

…But don’t let fear or a lack of confidence take over

Discussion

Remember the examples in Box 5 of Section 3.2. You should make sure you are not defining yourself by previous mistakes, or avoiding challenging yourself because it is out of your usual comfort zone.

Don’t internalise the expectations of others around you

Discussion

Sometimes individuals will openly state their expectations for you (for example “you should be aiming for promotion within a year”). At other times, you may feel there are implied expectations (for example, “I got this job because of my high level of chargeable hours, so I need to keep increasing them”) You can’t always assume that you are interpreting these expectations correctly, but even if you are, they don’t have to rule your decision-making process. It is important to remember they are other peoples’ perspectives, and that yours can be different.

…But let people help you bear the burden

Discussion

It is a good idea to chat through your thoughts and emotions with others, to get their input and perspective. This could be work colleagues or friends.

Think outside the box

Discussion

Don’t assume because something is the norm it has to be (or even should be) that way. For example, if you are offered a promotion, it’s easy to instantly agree because of the status and financial rewards involved, but if you are agreeing for those reasons, there’s some evidence it is unlikely to make you happy or fulfilled. This is known as “extrinsic” as opposed to “intrinsic” motivation (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

In practical terms, a key part of handling responsibility can be ensuring that you are organising and managing your time appropriately and maintaining an effective work-life balance This video gives some practical tips from legal professionals on getting the balance right.

Organisation and balance

Transcript

5. Dealing with stress

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- 1 activity on “Identifying stress levels and their impact

- 1 video.

You should allow yourself 30 minutes to complete this section.

"So that could be if I was subjecting myself to excessive levels of stress then in the long term there will be a physiological, psychological impact."

"…stress and tiredness…are the sort of almost preconditions for lots of people in their legal work."

Stress is a common part of all legal practice. In fact, that is not an intrinsically bad thing. There is evidence that a certain amount of stress has an important role in motivating individuals at work and assisting them in working more efficiently. This probably explains why many lawyers will state that they “work better under pressure”.

One way to visualise stress levels is to think of an inverted U shape. The top of the inverted U represents the optimum level of stress for performance and productivity. Once you begin to traverse down the side of the U, the danger is that your stress levels are becoming too high and may begin to have a negative effect in both your work and personal life. Research convincingly supports the inverted U-shaped curve hypothesis about stress and performance, with studies showing that, after a certain point, stress impairs cognitive performance (Lupien, Maheu, Fiocco & Schramek, 2007).

There are a number of tools you can use to identify your current stress levels, including this questionnaire

Activity 3: Identifying stress levels and their impact

Part 1

The inverted U shape below has three text boxes – one indicating low stress, one indicating optimal stress, one indicating high stress. Spend a few minutes thinking about times you have experienced each of these conditions and make a note in the text boxes of:

- When you last experienced this level of stress

- What sort of thoughts, feelings and emotions you had at that time

- What impact (if any) you think experiencing this level of stress had on you (this could be physically, mentally or emotionally)

- What helped you deal with this stress?

- What got in your way?

Comment

By completing this exercise, you will have identified some stressors and their impact, but also will have considered what helped and hindered your response to this stress. This kind of self-reflection is useful in building up personal resilience and strategies for coping with stressors.

Here are some additional suggestions if you think you are experiencing high levels of stress:

- Think about whether you are attending to the basics of your wellbeing – sleep, healthy eating, exercise, hygiene.

- Are you communicating and establishing connections with supportive members of your family, friends and colleagues? Can you reach out and begin a conversation about the impact of work and strategies that are helpful with coping?

- Are you attuned to the possibility of withdrawal and isolation – if it has been a while since you engaged socially, it may be time to schedule a low-key meet-up with friends or family.

- Create time and space for reflection – meditation, mindfulness, prayer, reading, listening to music – schedule just 10 minutes in the first instance if you don’t have much time.

- Maintain the daily routines that you enjoy and allow for predictability – for example, the morning coffee at the bakery or reading the newspaper on the train.

- Look at whether your organisation offers confidential organisational support such as an employee assistance program. LawCare also offer a free, independent and confidential helpline on 0800 279 6888.

Knowing how and when you experience stress and being able to identify the impact it may have can help you to monitor you stress levels in the workplace and be more proactive in ensuring they stay within acceptable boundaries or within your zone of tolerance. If you find you are struggling to maintain this then it is important to seek help from your GP or another source (see “Additional resources” for further suggestions).

Part 2

Using the text boxes below, list your top three coping strategies. In other words, the three ways you usually try to deal with high levels of stress (don’t worry if you can only think of one or two). Then identify one advantage and one disadvantage of each strategy you identified.

| Coping strategy | Advantage | Disadvantage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | |||

| 2. | |||

| 3. |

Comment

You may have identified a range of coping strategies. In some recent research by the authors, two strategies that were referred to were compartmentalisation (separating out work and other parts of your life into separate “boxes”) and rationalisation (trying to rationalise your emotional response to a situation by labelling it as illogical or irrelevant). Although these can be useful strategies, they really represent ways to put things to the side and ignore them (compartmentalising) or explaining them away (rationalising). Therefore, it is also important to identify and implement other coping strategies which are focused on making changes and empowering yourself to deal with stress.

In the focus groups the authors ran with LawCare, other coping mechanisms included using alcohol to unwind and having a dark sense of humour about issues:

"And you go out for a drink with colleagues and everyone laughs about really horrible, stressful things that you’ve been through, and the coping mechanism is to laugh and have a glass of wine."

There were also indications of other (very unhealthy) coping mechanisms:

"Substance abuse, running themselves into financial difficulty, dysfunctional relationships."

Although socialising and unwinding with colleagues can have positive effects, there are dangers of becoming over reliant on alcohol to help cope. Using humour can also become another way to try and ignore the impact your experiences are having on you. However, humour can also be a major stress reliever and an acceptable way to deal with, or begin conversations about, topics that are otherwise hard to talk about.

One different strategy would be to identify one way to effect a change in your workplace and set a deadline to do it (don’t forget to put a reminder in your diary or phone). This could involve organising a social gathering at work or a coffee morning for a charity that is meaningful to you, pinning something uplifting to the noticeboard or fridge, doing something nice or unexpected for a colleague, bringing in a cake to share with colleagues, having a social chat with a colleague or complimenting someone on their skills. If you usually have lunch in front of your screen, maybe it is time to start going out with colleagues to eat occasionally as well.

This video gives some suggestions from legal professionals on handling stress.

Handling stress

Transcript

5.1 Other mental health issues

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- 1 video.

You should allow yourself 10 minutes to complete this section.

Although stress is possibly the most common issue which individuals experience in legal practice, there are a number of other potential issues that can arise. It is important to be aware of these, so that you can identify when you (or a colleague) may need to obtain further help and support. Some of the most common issues include:

- Anxiety (intense, disproportionate and/or distressing feelings of worry)

- Depression (low mood impacting on daily life)

- Vicarious/secondary trauma (the negative psychological signs and symptoms that can result from on-going involvement with traumatised individuals)

- Burnout.

Unlike stress, where a certain amount can be beneficial, burnout is bad. It’s often the reason why people gradually become ineffective and then leave certain professions. According to one of the most well-known burnout researchers (Maslach and Jackson, 1981), the three components are:

- Emotional exhaustion (anxiety, irritability, loss of appetite, fatigue, insomnia);

- Cynicism and detachment (not caring, depersonalisation, reduced empathy);

- Feelings of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment (reduced or low productivity, poor performance).

Recent evidence indicates that females may experience higher levels of emotional exhaustion than males and they may experience emotional exhaustion as their first warning sign of burnout (Houkes, Winants, Twellaar and Verdonk, 2011). In contrast, males may experience higher levels of cynicism and detachment than females and may experience this as their first warning sign of burnout. So how you experience burnout may differ depending on your gender (and other factors).

First-hand accounts of legal professionals dealing with some of these issues are available on the LawCare website. This video explains when you may wish to consider seeking further support.

Considering further support

Transcript

6. Becoming a reflective practitioner

This section includes:

- Explanatory text

- Information box on “What is self-reflection?”

- 1 activity on “Moving forward”.

You should allow yourself 30 minutes to complete this section.

In the Introduction section to this part of this course, we suggested that you make a note of some existing strengths and developing areas as you worked through these materials. If you did this, well done! If not, you were probably applying the common technique which legal professionals use of scanning large volumes of information to extract key points as quickly as possible. Unlike in professions such as teaching, traditionally legal professionals have not been taught to build-in time for self-reflection. However, this is gradually changing with Continuing Professional Development requirements in many parts of the profession requiring this skill.

What is self-reflection?

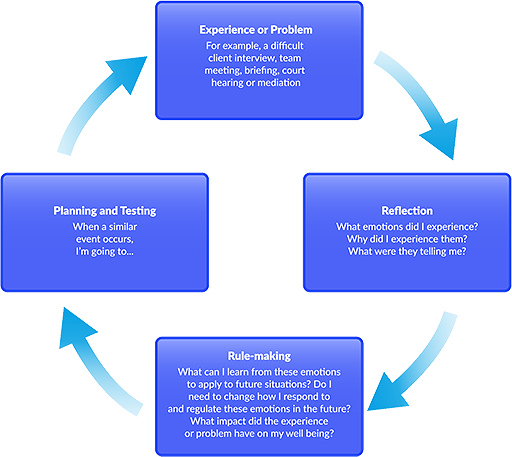

There are different types of reflection, including “reflection-in-action” and “reflection-on-action” (Schön, 1990). The former concerns how you think and deal with situations while you are in them. The latter is about looking back on what happened afterwards, to see what you can learn about it for the future (as you have done in the activities in these materials). It is this type of experiential learning which this course is encouraging in relation to emotional competence and professional resilience more generally. One way to picture this is as a cycle (based on Kolb, 1984 and Maughan and Webb, 2005):

Of course, you should not reflect on your emotional responses in isolation, you also need to factor in what your thoughts and actions were as well. However, within the legal profession, it is the reflection on emotions (and, by extension, wellbeing) which is probably most likely to be ignored or skipped over, despite the evidence of its importance.

This reflective way of thinking may come more easily to some legal professionals than others, but it can become ingrained through practice. This video demonstrates the importance of self-reflection in your professional life, and the challenges it can involve.

Self-reflection in practice

Transcript

The final activity in this part is designed to help you practice reflective thinking over the next few weeks.

Activity 4: Moving forward

In the text boxes below, make a note of the following:

These actions could include revisiting these materials regularly, making changes in the way you practice or even seeking outside help if you have identified this may be needed. You should try and be as specific as possible so that you can easily hold yourself accountable.

Make a note of each of your answers (and the accompanying deadline) in your diary, calendar or on any other device you use to organise your time. Make sure you set reminders to keep you focused.

There is no final comment on this activity, because we hope it won’t be the end of your thinking around emotional competence and professional resilience. Well done on working your way through this part. You can access the other parts of the course resources About the Authors and Additional resources as well as joining the on-going conversations at #FitforLaw and in our Fit for Law Facebook group.

Final questionnaire

We would also be grateful if you could complete an anonymous questionnaire giving feedback on this course. The responses will be used to help us to continue to develop Fit for Law.

References

Acknowledgements

Images used on the course

Scales Of Justice – Fit for Law logo: Lawcare Ltd.

Media Headlines: TFA/Lawcare Ltd. Image based on: Team Emotional Intelligence: How to Avoid being a “Quarrel of Lawyers” (Thomson Reuters Legal Executive Institute, 2016)]; Emotional Intelligence: What can learned lawyers learn from the less learned? (The Barrister Magazine, 2013); Taking soft skills seriously (LexisNexis Future of Law Blog, 2015); oft Skills in a Hard Market (Counsel Magazine, 2016); City law firm brings in emotional intelligence training to ward off threat from robots www.legalcheek.com, 2016); Loving legal life: empower yourself with empathy (The Lawyer, 2018); Lawyers given lesson in how to show their soft side as they face robot competition (The Telegraph, 2016)].

Open Book illustration: © Pinkpant | Dreamstime.com

Pros and cons figure: nasirkhan | 123RF Limited.

Dancing Heart and brain render: © FabioBerti - Can Stock Photo Inc.

Anger iceburg: ©2018 The Gottman Institute. All Rights Reserved.

Emotional Strength cartoon: Baloo -Rex May. © CartoonStock Ltd. 2018 All Rights Reserved.

The Zone of tolerance: Bacon, T. Dr (2016) Emotion Regulation: Managing Emotions. Based on materials developed for The Resources Group: An Emotion Regulation Skills Group. NHS Fife.

Know your limit: © 2007 Mike Bannon www.mordantorange.com

Businessman adjusting cufflink: CHAjAMP | Shutterstock, Inc.

Messy Office Desk: Image by Oliver Menyhart from Pixabay.

Money on her mind pound symbol: DJTaylor | Shutterstock, Inc.

Emotional self reflection: Lawcare Ltd.