Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 4:18 AM

Study Session 3 Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in WASH

Introduction

In Study Session 1 you read that one of the categories of people most likely to be excluded from WASH are women and girls. This study session examines the issues associated with gender and inequality in society and the traditional roles of women and men, particularly in relation to WASH in Ethiopia. You will also learn about the reasons why the empowerment of women is essential for future development of WASH services.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 3

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

3.1 Define and use correctly all of the key terms printed in bold. (SAQs 3.1 and 3.3)

3.2 Outline gender equality issues for WASH in Ethiopia. (SAQ 3.1)

3.3 Define empowerment and give examples of women’s empowerment in WASH. (SAQ 3.2)

3.4 Explain why monitoring gender equality in WASH is important. (SAQ 3.3)

3.1 Gender roles and equality

As you know, men and women have different reproductive organs and also differ in other aspects of anatomy and characteristics such as facial hair. These differences define a person’s sex, but they do not define their gender.

You may think that the terms gender and sex are the same and can be used interchangeably, but this is not the case. Sex is a biological category based on physical differences and different reproductive functions. Gender is not defined by biology but is based on the roles in society, both in public and private life, that are associated with being male or female. It refers to the social and cultural attributes and behaviours that we tend to assume are typical of men or women. The Training Manual on Gender Planning in WASH (MoWIE, 2017) lists some examples of gender-related assumptions including:

- Girls are gentle/boys are tough

- Men have the power/women do not

- Men are logical/women are emotional

- Women are shy/men are not

- Men should work outside the family/women should work within the family

- Men are leaders/women are not.

These attributes are not predetermined but arise from traditional expectations of individuals and society, which assign these roles and relationships to men and women. From early childhood, girls and boys learn that these are their expected roles and there is often considerable social pressure to conform to these norms. However, it is important to note they are not fixed and can be changed.

These gender-related assumptions about men and women give rise to the traditional roles they are expected to play in society. Typically, men are expected to earn money for the family but not to undertake domestic tasks such as cooking, cleaning and washing clothes, or to help with childcare. If they have community roles, these tend to involve management and leadership.

Women’s roles are more complex. They have the main responsibility for looking after the children and home, and possibly the care of older, sick or disabled relatives. In addition, they undertake paid work or other activities to provide an income, and they frequently participate in community organisations and activities. This combination of responsibility is described as women having a triple role (Moser 1995, cited in Coates 1999). The three roles are:

- reproductive role – childbearing and caring for children, unpaid domestic tasks to sustain the home (cooking, fetching water, cleaning, washing clothes, etc.)

- productive role – work done to produce goods and services for consumption or trade

- community role – tasks and responsibilities carried out for the benefit of the community, usually voluntary and unpaid.

Some of these tasks are illustrated in Figure 3.1.

Case Study 3.1 Womitu’s busy life

Womitu is 21 years old and lives in Derashe town. Her parents believe that girls should get married early, so they organised an arranged marriage for her when she was 15, which meant she had to drop out of school. After a year, Womitu gave birth to a baby boy. Her husband worked as a vegetable farmer and life was not easy for Womitu, as she was economically dependent on her husband. After a while, when she knew her baby was growing well, she decided to sell some fresh vegetables in the village and earn additional money to support her family. Her husband agreed with the idea, and Womitu started the business, leaving her baby at her parents’ house. After a couple of months, Womitu joined a cooperative so she could access a loan to strengthen her business. As well as her family and business commitments, Womitu is sociable and an active participant in community associations like ekub and edir.

Read Case Study 3.1 and then briefly describe the different roles played by Womitu.

Womitu has a reproductive role caring for her son and the family home. She grows and sells vegetables in a productive role that brings in income. And she has a role in the community as a member of the cooperative and the community associations.

Even though both women and men do productive work that brings income into the household, the work of women is typically lower paid and given little recognition. Women tend to get paid less even if they are doing the same job as a man. In Ethiopia, the National Labour Force Survey of 2013 found that average monthly earnings were nearly 50% more for men than women (CSA, 2014). There is also inequality in unpaid tasks at community level where men typically have leadership roles while women do organising and support work.

These traditional gender roles contribute to the unequal relationship between men and women. Women generally have less access to resources, less power and are excluded from discussions and decisions at all levels of society, from their own household level upwards. The goal for an equal society, therefore, is to acknowledge that women have the same human rights as men. Equality means everyone is treated in the same way, so gender equality means men and women have exactly the same status, rights and opportunities. Working towards gender equality means adopting policies and practices that change the traditional gender roles of men and women in all aspects of life, of which WASH is one of the most important.

3.2 Gender and WASH

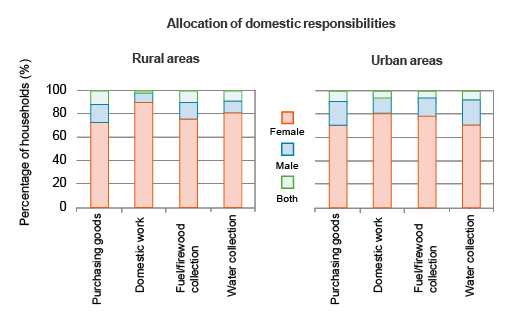

Part of women’s triple role is having responsibility for domestic tasks and care of the home. Figure 3.2 shows how unequal the allocation of tasks is between men and women.

Look at Figure 3.2. What is the proportion of households where women have sole responsibility for water collection?

Women have sole responsibility for water collection in about 80% of rural households and about 70% of urban households.

Water collection is one of the most time consuming of these domestic tasks. Many women and girls, especially in rural areas, spend hours each day collecting water for the family. This not only prevents them from doing other more productive work or attending school but can also cause physical damage because of the heavy weight of a full jerrycan. There are other disadvantages. Women, especially in rural communities, spend so much time on domestic chores including fetching water that they have no time to get involved in public decision-making processes, so even if social and cultural attitudes that discourage or prevent their participation could be changed, they have no time to take part.

There is also a gender divide when it comes to sanitation. If latrines are inadequate or non-existent, this has a much greater impact on women than men. Women and girls may wait until dark to relieve themselves, which can be dangerous and make them vulnerable to attack. They may also avoid eating and drinking during the day which can damage their health.

Sanitation also affects school attendance. The lack of separate toilet blocks for girls and boys in schools is widely believed to contribute to poor attendance by girls and makes them more likely to drop out of school entirely. Guidelines recommend girls’ and boys’ blocks with at least 20m between them, and with lockable doors facing in opposite directions (MoE, 2017b). They also require proper facilities for menstrual hygiene management. During their menstrual period, girls and women need access to safe and affordable menstrual absorbents and private facilities for the disposal and/or washing of materials used to absorb menstrual blood, and access to facilities for washing themselves. Despite the guidelines, these requirements are frequently overlooked in the design and construction of school latrine blocks and are also neglected in shared public facilities. Remember facilities also need to be accessible for women and girls with disabilities.

One of the main reasons for the neglect of women’s needs is their exclusion from discussions about the planning and design of WASH services. You will remember from Study Session 1 that this was part of the definition of exclusion. Usually it is men who make decisions about the allocation of finances and they may not prioritise issues that affect women’s lives but not their own. Women are often excluded from participation in decisions about water supply, sanitation and hygiene, even though they are the ones whose lives are most affected. Social attitudes also affect the way in which WASH professionals address issues like menstruation or fistula which have a lot of stigma in many communities. This has a big impact on women and girls.

3.3 The context in Ethiopia

The importance of gender equality has been recognised in Ethiopia since the mid-1990s. The Ethiopian Constitution (1995) and Ethiopian’s Women’s Policy (1993) established the principles of equality of access to opportunity. The Ministry of Women and Children Affairs also dates its origin back to 1993 (MoWCA, 2018). This foundation has been followed in other government policies and strategies. These include the National Action Plan for Gender Equality (NAP-GE), which covered the period from 2006 to 2010 and has since been incorporated in the Plan for Accelerated and Sustainable Development to End Poverty. Similar principles are also part of the Growth and Transformation Plans I and II, Health Sector Transformation Plan (FMoH, 2015) and the One WASH National Programme (FDRE, 2013), among others.

The NAP-GE worked to achieve the objectives of gender equality expressed in the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action (BPA). The BPA was an international programme that emerged from a United Nations’ Conference on Women held in Beijing, China in 1995. It established the concept of gender mainstreaming, which is now a key component of Ethiopian national policies.

In Study Session 1 you read that mainstreaming can be defined as ensuring that an issue or topic is at the centre of consideration for any plan or project. Gender mainstreaming, therefore, means giving equal priority to the interests of both genders at all stages of a process, including development, planning, implementation and evaluation. The National Gender Mainstreaming Guidelines describe it as:

. ..a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s needs, priorities, concerns and experiences an integral part of the planning, implementation and monitoring and evaluation processes. This helps to ensure that development outcomes benefit men and women equally and that gender disparities are not continued. Gender mainstreaming seeks to ensure that institutions, policies and programs involve women and men equally, and respond to the needs and interests of all members of society. (MoWA, 2010, p. 28)

What practical steps have been taken in Ethiopia to put gender mainstreaming policies into practice? Here are two examples.

In the health sector, since the mid-2000s, more than 38,000 female Health Extension Workers (HEWs) have been deployed in more than 15,000 rural kebele health posts (Haile, 2014). Part of their role is to support their communities in efforts to improve hygiene and public health by installing pit latrines and advising families on good hygiene practices. HEWs are supported by the Women’s Development Army (WDA). The WDA is made up of ‘one-to-five’ networks of women. Each trained woman trains five other women from nearby households, who encourage their neighbours to change their practice by building latrines and setting up separate cooking spaces.

In the WASH sector, there is positive discrimination in favour of women in the membership of community water, sanitation and hygiene committees (WASHCOs). The One WASH National Programme requires that women are well-represented and elected to serve as officers of WASHCOs (FDRE, 2013). Furthermore, it states that 50% of WASHCO members should be women in decision-making positions. Despite this policy, technical and senior positions are still largely held by men. In a comparative study of twenty WASHCOs, researchers found that only six were led by women and, of those six, in two cases it was the husbands of the women who actually led the committee leaving only four out of twenty with genuine female leaders (Haile et al, 2016). Women were more often elected as treasurers because they were believed to be more trustworthy with money but community perceptions were that women did not have time to take on the role of chair because of their domestic duties and because they were not considered to be strong leaders.

There is still a long way to go but gender equality in national policies throughout the world now has further support and incentive with the Sustainable Development Goals and especially Goal 5 (see Figure 1.4 in Study Session 1). The first target of Goal 5 is to ‘End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere’. The rationale for the goal is explained like this:

Ending all forms of discrimination against women and girls is not only a basic human right, but it is also crucial to accelerating sustainable development. It has been proven time and again that empowering women and girls has a multiplier effect, and helps drive up economic growth and development across the board. (UNDP, n.d.)

3.4 Women’s empowerment in WASH

You may have noticed the phrase ‘empowering women and girls’ in the explanation of Goal 5 of the SDGs. This is an essential part of the move towards gender equality. Women’s empowerment means giving power to women and girls so they can play a significant role in society. It means women and girls participating actively in socioeconomic and political processes. And it means finding ways to ensure that women are confident, that they are given a voice in society, and their opinions are respected (GADN, 2016). ‘Women’s empowerment is realised when women react to gender discrimination, overcome it and move forward to gain greater control over their own lives’ (MoWA, 2010).

But how do we achieve this goal? There are many activities that can empower women including supporting women’s groups and making sure that women have a chance to discuss WASH issues together so they can have a stronger voice in committees and more influence on decisions. Other ways of moving towards women’s empowerment are:

- Improve WASH services

- Challenge traditional gender roles

- Women role models

- Improve education

- Financial support.

Each of these is described in more detail below.

3.4.1 Improve WASH services

Women and girls often spend many hours a day fetching water. Improving WASH services creates opportunity for women to do other things with their time and empowers them by freeing them from the daily drudgery of water collection. It would give them time for other more productive purposes, such as working to bring in income or participating in social, political and community activities.

3.4.2 Challenge traditional gender roles

Unequal power between women and men is closely linked to their traditional gender roles. The assumption that women cannot be leaders and decision makers must be challenged. Changing people’s beliefs and behaviours is a slow process, but it can be achieved with education and training that raises awareness of gender issues. Case Study 3.2 is a good example of the transformative effect of training in women’s participation in WASH.

Case Study 3.2 AIRWASH project

The objective of the Amhara Integrated Rural Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (AIRWASH) project was to enhance participation of the community, and women in particular, in WASH-related activities. The project was an initiative of the Swiss NGO, HELVETAS.

The novel approach of this project was to train couples together so that husbands and wives gained a better understanding of each other. 26 couples and 3 single women from Meha kebele received training on gender issues and gender mainstreaming. In particular the training focused on the gender division of labour, the burden of water collection on women and girls, and women’s unpaid domestic work. The training was delivered by a combination of structured taught sessions, an exchange visit to a nearby community known to be a model for gender equality, and community discussions.

The project had many positive outcomes including:

- Both men and women changed their perceptions and understood that women can contribute to decision making.

- The women’s self-confidence improved and their sense of ownership of WASH services increased.

- Women got involved in site selection for new water points and worked with the men to set up operation and maintenance systems.

- Three out of the five members of the WASHCO are women; their husbands no longer take over their role on the committee.

- Couples who received the training share the household tasks (Figure 3.3).

- Women participate actively in community meetings and openly express their views. They are no longer just passive receivers of information.

Overall, by training couples together, the project enabled men and women to understand each other’s roles and make changes based on mutual respect within the household.

(Adapted from Mihretu and Gedif, 2016 and Mihretu and Moser, 2017)

3.4.3 Women role models

Part of the AIRWASH project training was a visit by the couples to a nearby model community where women were already full participants in WASH decision making. This enabled them to see women in leadership positions, which was empowering for the female participants and informative for the men. Female role models give other women confidence to take on similar roles themselves because it encourages them to think ‘if she can do it, then so can I’. WASHCOs can provide examples of women role models where the female members of the committee take on the role of chairperson and not just the supporting roles of treasurer or secretary. Strong female role models may also be found among women in senior positions in government, business and other walks of life.

3.4.4 Improving education

WASH and education for girls are interconnected in several ways. Poor water and sanitation facilities at schools are one reason why girls tend to drop out of education before they have completed their schooling. If all schools had facilities that met the required guidelines this would improve school enrolment and attendance by both girls and boys.

If girls are successful in school and possibly continue to college or university they will be empowered by their education, be more independent in their life choices, have wider employment opportunities, and reach positions in society where they have more influence. Haile (2014) states that ‘educating girls is the single most effective tool for strengthening economic productivity’.

3.4.5 Financial support

The challenges faced by women in society often make it difficult for them to break out of their traditional roles. However, there are many examples in Ethiopia of small-scale enterprises owned and run by women, which have been made possible by receiving financial support at the start. Case Study 3.3 is one such example.

Case Study 3.3 Wukro women in business

In the town of Wukro in the Tigray region, Helen, Meaza and a friend have started up a new business making and selling reusable sanitary pads (Figure 3.4). Their enterprise is supported by a WASH programme implemented by UNICEF with World Vision. The women were chosen by a women’s association, trained by World Vision and then provided with sewing machines and materials. They are supplying seven schools with the washable sanitary pads and also sell them to local women.

The new business has multiple benefits for women. It helps girls and women by providing effective, handmade sanitary pads that can be washed and re-used. It also generates income for the three women entrepreneurs.

(Adapted from Carazo, 2017)

3.5 Monitoring gender equality and women’s empowerment in WASH

Monitoring means collecting data to find out if progress is being made towards achieving an aim or objective. It is important because it enables evaluation of the success or otherwise of a strategy, project or other activity. People and organisations responsible for monitoring often use indicators as a means to collect useful data. An indicator is something that can be counted, measured or assessed and provides evidence of progress towards achieving a specific goal.

Data and indicators can be classified as either quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data, as the name suggests, is concerned with measurable quantities such as total numbers, percentages, and averages. Qualitative data is not based on numbers but on assessments of people’s opinions, attitudes, values and beliefs.

Quantitative methods of data collection focus on what can be counted; common sources are censuses, surveys and administrative records. Typical sources of qualitative data are interviews and focus group discussions.

3.5.1 Gender equality indicators

A ‘gender-responsive’, ‘gender-sensitive’ or ‘gender-related’ indicator measures changes relating to gender equality over time (Demetriades, 2009). Gender equality indicators can be quantitative, based on sex disaggregated statistical data or they may be qualitative, for example attitudinal changes to gender equality. Examples of quantitative indicators are male and female wage rates or school enrolment rates for girls and boys. Qualitative indicators might include an assessment of women’s experiences of lack of sanitation facilities, or men’s and women’s views on the causes and consequences of domestic violence.

What are ‘sex disaggregated data’?

Sex disaggregated data are data that are collected and recorded separately for male and female members of a population.

All indicators should be disaggregated by sex wherever possible so that the different experiences of men and women can be known. However, data for gender-related indicators are not readily available (Haile, 2014). Beyene (2015) provides a national assessment of participation of women and girls in the ‘knowledge society’ in Ethiopia. Her study collates quantitative and qualitative data from many sources about variables such as women’s health status, social and economic status, women’s access to resources, access to opportunities, level of political participation and access to science and technology education, among many others. However, for several of the topics Beyene comments that sex disaggregated data is scarce. As we have noted earlier, very little information is available that is disaggregated by both sex and disability even though the experiences of disabled men and women are different.

How can this situation be changed? In accordance with the general policy of gender mainstreaming, gender-related indicators can be incorporated into any policy, programme or project. The National Guidelines (MoWA, 2010) include recommendations for monitoring and evaluating gender mainstreaming for policies, organisations and programmes. Table 3.1 shows a small extract from these guidelines for the activity stage at programme/project level.

| Checklist | Indicator |

|---|---|

| Does the activity planning phase involve both women and men? | Proportion of women and men involved in planning phase |

| Are there specific activities included to ensure gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE)? | Specific activities planned to ensure GEWE |

| Are the planned activities considering the household workloads of women? | Women's workloads considered in the planned activities |

| Are the planned activities data sex disaggregated? | Sex disaggregated data incorporated in the planned activities |

| Do the programme/project implementers receive gender-mainstreaming training so that a gender perspective is sustained throughout the implementations process? | Type and number of gender mainstreaming trainings given to implementers |

| Do women and men from the community participate equally in the implementation? | Number and proportion of women and men participated from the community |

In WASH, the One WASH National Programme has two gender-related indicators within its results framework that are assessments of the proportion of women on WASHCOs/Hygiene and Sanitation Community Groups and on Water Boards (committees with responsibility for water utilities). In both cases, the indicator is the percentage of committees with 50% of their members being women in decision-making positions (FDRE, 2013).

There are quantitative and qualitative elements to these indicators. The quantitative element is to find out how many committees have women as at least half of their membership. But it is more difficult to assess their role and position. Researchers could ask questions such as ‘what percentage of committee chairpersons are women?’ or ‘what percentage of WASHCOs have all leadership positions filled by women?’ But these questions would not assess the level of participation by all the women members. This is where qualitative indicators can help to show whether women’s participation is just a gesture or is active and meaningful (RWSN, 2016). One approach to improving the monitoring of gender in WASH could be to create more detailed checklists, developed from lists similar to the extract in Table 3.1, but with questions specific to WASH and with qualitative as well as quantitative indicators.

Summary of Study Session 3

In Study Session 3, you have learned that:

- Sex is a natural attribute that identifies a person as male or female. Gender is a social attribute ascribing some characteristics or norms and modes of behaviour to men and women.

- Traditional gender roles result in men and women not being treated equally even though they have the same human rights.

- Gender inequality is a major issue in WASH. Women are usually responsible for fetching water and inadequate sanitation has greater impact on them than men, and yet they are excluded from decision-making processes.

- In Ethiopia, gender mainstreaming is government policy, but this has not had a significant impact in practice.

- Women’s empowerment means enabling women in a number of ways to overcome gender discrimination and take control of their lives.

- Monitoring is important for assessing changes in gender equality. Both quantitative and qualitative data are needed but gender-related data is often lacking.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 3

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 3.1 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1 and 3.2)

Rewrite the paragraph below using terms from the list provided to fill in the gaps.

gender; gender equality; gender mainstreaming, menstrual hygiene management; triple role; women’s empowerment

Women have the burden of a …………… in society that expects them to do unpaid work at home, productive work that brings in money, as well as contribute to community life. In WASH, women are at a disadvantage because traditional …………. roles assume men are the leaders so women are excluded from discussions and decision-making processes about WASH, even though they are the main users. The needs of women and girls are often disregarded in schools where latrine facilities, if they exist at all, are not designed according to guidelines and lack facilities for …………………….. Despite government ……………………… policies and growing awareness of the benefits of ……………………………, there is still some way to go to achieve ………………… in Ethiopia.

Answer

Women have the burden of a triple role in society that expects them to do unpaid work at home, productive work that brings in money, as well as contribute to community life. In WASH, women are at a disadvantage because traditional gender roles assume men are the leaders so women are excluded from discussions and decision-making processes about WASH, even though they are the main users. The needs of women and girls are often disregarded in schools where latrine facilities, if they exist at all, are not designed according to guidelines and lack facilities for menstrual hygiene management. Despite government gender mainstreaming policies and growing awareness of the benefits of women’s empowerment, there is still some way to go to achieve gender equality in Ethiopia.

SAQ 3.2 (tests Learning Outcome 3.3)

Genet was married at the age of 20. She took care of her family every day, starting at 6 a.m. While looking after her baby girl, she prepared breakfast for her husband before he went to work. Then she went to fetch water and had to walk more than 3km to reach a source of clean water. When it came to decision making, her husband took the lead in everything.

Her life changed when the woreda administration started working with an NGO to address the challenges for women in the community. They built a water point nearby and provided training in assertiveness skills for women. They also engaged respected religious and community leaders in a dialogue about getting women involved in decision making. These opportunities gave Genet’s life a new dimension. She was able to teach her husband to share responsibilities at home and most importantly could access WASH facilities safely and easily. Community members noticed Genet’s transformative actions and appointed her to the WASH committee with responsibility for empowering other women to participate in meetings, community dialogues and campaigns to support women in the community.

What elements in this story demonstrate Genet’s empowerment?

Answer

Genet’s life was previously dominated by domestic chores including fetching water, but after the water point was built nearby she had more time for other activities. Assertiveness training gave her new skills and confidence. She was also able to persuade her husband to help at home, which again gave her more time. The change in attitude of the male community leaders opened up opportunities for Genet. She was appointed to the WASH committee with the important role of helping other women to become involved.

SAQ 3.3 (tests Learning Outcomes 3.1 and 3.4)

What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative indicators? Explain, with an example, why both are necessary for monitoring gender equality.

Answer

Quantitative indicators are measures that demonstrate change or progress towards a goal and are expressed in numbers. Qualitative indicators also demonstrate change or progress, but are concerned with attitudes and opinions and are usually expressed in words. Both are necessary for effective monitoring because quantitative indicators only tell part of the story. For example, monitoring gender equality in WASHCOs could use the number of women in the role of chair as an indicator, but this would not tell you how active or effective they were in the role.