Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 23 February 2026, 3:11 AM

Study Session 5 Participation and Partnership

Introduction

You will know from the previous study sessions that one of the most important principles of inclusive WASH is that people who would have been excluded in the past should be fully engaged and involved in all stages of the process of developing WASH services. In this study session you will learn about some of the ways in which engagement and participation can be achieved.

Learning Outcomes for Study Session 5

When you have studied this session, you should be able to:

5.1 Define and use correctly all of the key terms printed in bold. (SAQs 5.1 and 5.2)

5.2 Identify appropriate inclusive WASH facilities for households and institutions. (SAQ 5.2)

5.3 Carry out an accessibility and safety audit. (SAQ 5.3)

5.4 Describe the steps in planning and implementing inclusive WASH facilities. (SAQ 5.5)

5.1 Meaningful participation

In Study Session 1 you learned that inclusion in WASH means not only being able to access WASH services but also being able to participate in decision-making processes about those services. Participation means taking part or being involved in something, usually a decision or activity. Community participation, therefore, is a process of involving a community or its representatives in activities that have direct or indirect consequences on their lives.

5.1.1 Participation and meaningful participation

Why do we need to talk about meaningful participation? Sometimes so-called ‘participation’ does not actually succeed in allowing the people affected to be heard. Even if people are physically present at a meeting it does not mean they will feel confident to speak, or that others will listen to them and respect their views (Figure 5.1). Participation should be more than just passive listening, being the subject of data collection or providing labour.

In the WASH sector (and many others), there are ineffective participatory processes practised by service providers including government and non-government organisations. For example, an NGO may organise a community meeting and present the plans for a new project, but this does not allow the community to actively engage in the planning process. The community is shown the plan but they are not invited to change anything or be involved in decision making.

For changes to have positive impacts, it is a necessary condition that community representatives actively participate in the whole process – from initiating ideas to evaluating the outcomes. The community is in the best position to identify problems and formulate solutions and it may need some extra effort to ensure they are included. For example, you may need to consult separately with women to make sure they feel comfortable discussing their views freely, or make special efforts to seek out the views of people with disabilities. Meaningful participation, therefore, occurs when everyone in the community actively contributes to the planning, decision making, implementation and monitoring of a project.

Mamitu, 80, has almost given up hope of having a latrine that she can use with comfort and dignity. Fortunately, an NGO supporting old people has come to her village and identified her as one of the beneficiaries. She is told the NGO has a plan for her. What is your advice to the NGO?

Your advice should be to ensure the NGO involves Mamitu in the process by asking her to identify the problems she has had accessing the existing latrine. She should also be part of the solution, which means participating in designing the new latrine facility so she can access it easily.

5.1.2 Benefits of participation

The benefits of participation are closely linked to the benefits of inclusion that you read about in Study Session 1. If people participate fully in the water and sanitation planning and decision-making process, it will bring about change in them as people and to the community and the country in terms of improving health and productivity. It also contributes to the sustainability of new services because when you are part of the process, you own it and care for it. Meaningful participation produces better, more successful outcomes, as illustrated in Case Study 5.1.

Case Study 5.1 Bayu Muluneh and the borehole for Alefa village

Alefa, a village in rural Amhara, had not had a water supply nearby for nearly a century. Many agencies came to Alefa to develop underground water, but they were not successful; the drilling failed many times because they could not locate a site where water is available. Bayu Muluneh, aged 71, had almost lost hope of seeing safe water flowing through the tap in his village.

Two years ago a team from WaterAid and Water Action came to his village and asked elders, including Bayu, to help them select the site for drilling the borehole. The elders knew about sites where there had been springs many years before, but the springs had dried up because of changes in the climate. Based on this indigenous local knowledge, the team conducted further studies, and when they drilled the borehole they found a reliable water supply. Without the active participation of the elders in site selection, their efforts would have failed again.

5.2 Making community participation inclusive and accessible

Community participation is a common practice in rural areas when a given service provider, be it government or non-government, is planning to implement a project. This participation aims to introduce the project activities and mobilise communities to take part in the implementation process either by providing labour, as shown in Figure 5.2, or by making cash contributions. However, as noted above, this process is not always meaningful participation and frequently, it is not inclusive either. There are a number of possible reasons for this including:

- It does not involve representatives of all sections of the community.

- It does not involve community representatives in the planning and decision-making parts of the process.

- Even if people are present they may not be able to influence decisions because of the attitudes and beliefs of others, for example gender norms that mean women’s views are considered less important than men’s.

- The meeting place may not be physically accessible to everyone.

To illustrate how existing community participation practices could be transformed into inclusive participation, we have chosen examples from Ethiopia’s national approaches to promote safe water, sanitation and improved hygiene practices at community and institutional levels. These are Community-Led Total Sanitation and Hygiene (CLTSH), water, sanitation and hygiene committees (WASHCOs) and school WASH clubs. These approaches by their nature involve communities. Working further on these approaches can make community participation inclusive and accessible.

5.2.1 Community-Led Total Sanitation and Hygiene

Ethiopia has adopted Community-Led Total Sanitation and Hygiene (CLTSH) as a national tool to promote total sanitation. It aims to change the behaviour of everyone in a community to stop open defecation and encourage good hygiene practices. The goal is to achieve Open Defecation Free (ODF) status for the community where everyone has access to a latrine and no one defecates in the open at any time. The Federal Ministry of Health has published guidelines for implementing CLTSH. The process, outlined in Box 5.1, should be conducted by trained facilitators.

Box 5.1 CLTSH process

There are three main stages in CLTSH: pre-triggering, triggering and post-triggering (Kar and Chambers, 2008; FMOH, 2012).

Pre-triggering stage

At this stage, community representatives and the CLTSH facilitator discuss and agree a convenient time and place for village triggering and make plans for the whole process.

Triggering stage

The whole community gathers to discuss concerns relating to open defecation (OD). Together, the facilitators and community members make a transect walk. A transect walk entails walking through a village from one side to the other, observing, asking questions, and listening to the replies (Kar and Chambers, 2008). The purpose is to identify sites used for OD, hence the alternative name of shame walk, and to note the locations, types and conditions of any existing sanitation facilities.

Then the facilitators and community together prepare a map of the local area showing households, institutions and OD sites and helps everyone to understand the scale of the OD problem and the associated health risks (Figure 5.3). With the facilitators, they calculate how much human excreta they produce, known as ‘the shit calculation’. Triggering refers to the moment, also known as the ‘ignition moment’, when the whole community shares a sense of disgust and shame about open defecation. The facilitator helps them to come to the realisation that they quite literally will be eating one another’s faeces if open defecation continues.

The end of the triggering phase is agreement on actions to be taken. The action plan should have an agreed schedule and set of activities that everyone in the community commits to, including the construction of latrines with handwashing facilities and a commitment from everyone that they will use the new facilities at all times. A CLTSH committee of community representatives should be formed to take the process forward.

Post-triggering stage, including verification

The post-triggering stage is when the agreed plan is put into effect. The community may need additional support and training for construction of new facilities and for behaviour change in sanitation and hygiene practices. In this phase, a supervisory team will be formed to conduct routine monitoring and evaluation. They monitor the changes through review meetings, periodic reports, observations and interviews.

Verification is the stage when the village is assessed to find out if everyone is now using a latrine and washing their hands. Confirmation that open defecation has stopped and the certification of ODF status is a cause for celebration for the whole community.

In the CLTSH process, all households (men, women and children) and institutions (religious and social institutions) in a village should be included. However, to be truly inclusive it is essential that all members of the community are full participants, including people with disabilities and other marginalised groups (House et al, 2017). Although not specified in the FMoH guidelines, the process should go beyond general community participation and ensure that every group in the community is fairly represented and able to participate from the start.

For each of the three stages of CLTSH, can you suggest ways the process could be made more inclusive?

You may have thought of the following:

- Pre-triggering: (i) Include a deliberate step of considering the needs of different people in the community and agree on how to engage everyone in the whole process. (ii) Discuss the subject with women of different ages separately, without men present, to see if they have specific concerns about safety and privacy, and to find out their perspective.

- Triggering stage: (i) Transect walks, mapping and other activities must involve representatives of the whole community including persons with disabilities (that is, physical, intellectual and sensory impairments), elderly people (men and women), pregnant women, women and adolescent girls, children, and people with long-term sickness. (ii) Action plans must incorporate the different needs of all marginalised groups. (iii) The CLTSH committee should include persons with disabilities as members.

- Post-triggering: Persons with disabilities and representatives of any other marginalised groups should be part of the survey team for verification.

5.2.2 WASHCOs

It is a requirement in the One WASH National Programme that women are well represented and elected to serve as officers of WASHCOs (FDRE, 2013). Furthermore, it is stated that 50% of WASHCO members should be women in decision-making positions (Figure 5.4). Despite this national policy requirement, many WASHCOs have not achieved this target.

What reasons for the limited progress towards gender equality in WASHCOs can you think of?

There are several possible reasons including:

- The unequal power between men and women and assumed gender roles.

- Lower levels of literacy and education of women so they may need additional training in literacy or book keeping to be able to play a more significant role.

- Women do not feel empowered to challenge the system and put themselves forward.

Unlike the policy for women, there is no stated requirement to include persons with disabilities and other marginalised groups as members of WASHCOs. The criteria for establishing WASHCOs should be revised to explicitly include these groups. However, changing policy in this way is not quick or easy, and would need concerted effort by key stakeholders at national and lower levels, as well as increased awareness and changed attitudes among community members.

5.2.3 School WASH clubs

Supported by national policy, school WASH clubs are established by teachers and students to promote safe water and improved sanitation and hygiene practices in schools. They also encourage boys and girls to change their practices and share those changes with their families when they go back to their homes.

Where policy is being implemented effectively, and where there are NGO interventions, the participation of girls in the different clubs including WASH clubs is excellent.

The National School WASH Implementation Guideline specifies that five boys and five girls should serve as leaders for the WASH clubs, of which one boy and one girl should be representatives of students with disabilities (MoE, 2017b). However, this policy is not always adhered to, and greater effort is needed to encourage schools to follow the guidelines.

5.3 Changing attitudes to excluded people

From your study of this module you know that changing society’s attitudes to marginalised groups is a fundamental part of making progress towards inclusive WASH. This section looks more closely at how those attitudes might be changed.

5.3.1 Existing attitudes

Planners and decision makers exclude people, partly because their policies and the planning systems lack adequate consideration of marginalised groups, and partly because they lack knowledge of the conditions of these people in terms of access to safe WASH facilities. If considered at all, persons with disabilities are assumed to be insignificant. These negative attitudes are often shared by the wider community.

As you read in Study Session 3, attitudes to women can be dismissive and exclusive, and behaviour towards older women among some communities can be particularly shocking. They may be called witches and dishonoured rather than being supported and cared for, and they may be completely excluded from using communal facilities or participating in community gatherings. In some places menstruating women cannot attend religious meetings, as they are considered impure. This also includes attending community meetings, and therefore they are excluded from decisions that concern them.

5.3.2 Strategies for changing attitudes

Existing attitudes are perpetuated from generation to generation for no other reason than people accept the beliefs of their ancestors without questioning them. Challenging these bad attitudes is difficult, and change may not happen overnight; it requires commitment and persistence. In combination, the following strategies could be employed to try to influence people and change their thinking.

Collect evidence

To increase awareness, you need to have evidence to support the case that people are being excluded. This could be statistical evidence of the number of persons with disabilities of different kinds (i.e. data disaggregated by disability, sex and age), what factors contributed to their exclusion, and recommendations on how they can be included in the planning and decision-making processes that directly affect their lives. Evidence may also be available from an accessibility and safety audit. The output from the audit will provide details of the problems currently faced by persons with disabilities and how they might be resolved.

Raise awareness

Existing attitudes may result from a lack of relevant knowledge or thoughtlessness so a key part of changing them is to make people more aware of the situation of excluded people and the problems they face. This applies to people with disabilities and other marginalised groups and includes challenging assumptions about gender roles. This is where evidence can be helpful to support the argument that exclusion is wrong and inclusive WASH is a priority. There are many different ways to try to raise people’s awareness.

For communities: Evidence like that identified above could be presented to community meetings and included in the training of WASHCOs, CLTSH committees and WASH clubs. In the meeting, members of the local WASH Team (or members of the wider cabinet) could facilitate the discussion to help communities realise that persons with disabilities need safe WASH services for their day-to-day lives but face huge problems in accessing the facilities. It is also important for people with disabilities to be present at community meetings so they are more visible and can share their experiences with their fellow community members. However, they may need support to make sure they are able to be heard, and to make sure others listen to them.

To tackle people’s long-held beliefs about disability you could engage them in activities to convince them there is no link between disability and sin. For example, a woreda WASH Team, with the support of development partners, could identify a family that includes someone with a disability, provide incentives to encourage their participation and educate them that the cause of the disability is not the result of the wrath of God but something that could happen to anyone. Involving religious leaders in this process is of paramount importance.

For planners and decision makers: Studies to assess inclusion in WASH could be commissioned by planners to inform their decisions or can be conducted by development partners.

At public events: Major sector events such as the Multi-Stakeholder Forum and Global Handwashing Day can be used to promote the importance of inclusion in WASH planning and decision-making processes. Individual people with disabilities could be asked to give a speech where they could pass their messages to the wider audience.

Collaboration and partnership

All of the strategies described above are likely to be more successful if conducted in collaboration, either with individual people with disabilities, self-help groups, Disabled Persons Organisations (DPOs), women’s groups, or other organisations. This will ensure the real situation is understood including the problems faced in accessing WASH facilities and their associated risks, and how these affect daily lives. Partnering with like-minded individuals, groups and organisations will strengthen the effort to raise awareness and influence policies at national level, and change practices at lower levels.

5.4 Identify relevant stakeholders

How do you set about finding these like-minded individuals, groups and organisations? Working in partnership with others is more likely to succeed than the effort of any individual or organisation on their own, but first there is a need to identify the relevant stakeholders and potential partner organisations.

In Ethiopia there are six registered (DPOs) that belong to the Federation of Ethiopian National Association of Persons with Disabilities (FENAPD). FENAPD is an umbrella organisation that aims to improve coordination and collaboration between DPOs. FENAPD’s mission statement is to help persons with disabilities to avert disabilityrelated problems and improve their lives (FENAPD, n.d.).The six DPOs in FENAPD are:

- Ethiopian National Association on Intellectual Disabilities (ENAID)

- Ethiopian National Association of Persons Affected by Leprosy (ENAPAL)

- Ethiopian National Association of the Deaf (ENAD)

- Ethiopian National Association of the Deaf-Blind (ENADB)

- Ethiopian Women with Disabilities National Association (EWDNA)

- Ethiopian National Development Association of Persons with Physical Disabilities (ENDAPPD).

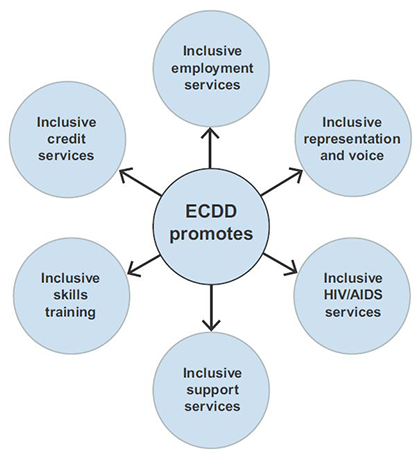

These DPOs also operate at regional level and, in addition, there are many CSOs and NGOs active in the regions and at other levels that have programmes and activities to support people with disabilities. One of these is the Ethiopian Center for Disability and Development (ECDD) which works in partnership with other organisations to promote disability mainstreaming in all aspects of life. The main areas of ECDD activities are shown in Figure 5.5.

There are also national organisations promoting women’s rights and the empowerment of women. For example, the Organization for Women in Self-Employment (WISE), based in Addis Ababa, provides training, advice, access to micro-finance and other support to help women set up cooperatives and become successful entrepreneurs (WISE, n.d.).

5.5 Sustaining inclusive WASH

If and when inclusive WASH provision is achieved, it is important that it is sustainable or, in other words, that the systems and processes in place will continue to be effective into the future. There are many factors that can affect sustainability, many of which apply to all WASH provision. These can be categorised as financial, environmental, institutional, technological and social factors.

5.5.1 Financial factors

WASH services, whether inclusive or not, require some level of financial contribution to ensure their maintenance and sustainability. In Study Session 1 you read that affordability is one of the reasons why some people are excluded. To enable these people to participate in the process of making inclusive WASH facilities durable and long-lasting means providing support for them either to engage in income-generating activities or, if it is appropriate and necessary, exempting them from financial contribution.

5.5.2 Environmental factors

Environmental factors affecting water facilities include water scarcity, which can result in wells drying up and is more likely if the wells were originally constructed during the rainy season (Addis, 2012). If this is due to poor site selection, the success of future water supply projects could be improved with proper hydrogeological surveys and by involving local people in the selection of sites. This may be older people, as you read in the story of Bayu in Case Study 5.1, and women because they know the water sources in their locality.

5.5.3 Institutional factors

Institutional factors include community management structure (e.g. WASHCOs), the availability of bylaws and guidelines. Most rural communities in Ethiopia have limited knowledge of these things so they require support and training to improve their awareness. WASHCOs need adequate information about how to engage with planning and budgeting processes at regional and woreda levels and how to hold responsible agencies to account.

5.5.4 Technical factors

Responsibilities for the operation and maintenance of water facilities are assigned to different tiers of government: major maintenance by the regional bureau, simple maintenance by the woreda water office and/or by enterprises engaged in water scheme maintenance; and minor preventive maintenance by the WASHCO or its assigned caretaker. Bottom-up reporting systems and accountability mechanisms and top-down management and technical support need to be strengthened to ensure sustainability.

5.5.5 Social factors

Social acceptance is a basic foundation for sustainability. If promotional activities result in acceptance of inclusive WASH among the society or community, it means that there is ownership of the facilities which in turn, contributes towards ensuring sustainability.

Sustainable inclusive WASH for all is the goal that all WASH sector actors should be aiming for. It requires greater knowledge and awareness of the challenges of inclusion, as well as commitment and persistence from all those concerned. We hope that your study of this module will help you contribute to achieving this goal.

Summary of Study Session 5

In Study Session 5, you have learned that:

- Meaningful participation occurs when everyone in the community actively contributes to all stages of a project.

- If people participate fully in WASH planning and decision-making processes, they are more likely to be successful and will bring many benefits including improved health and productivity.

- Community participation is frequently not inclusive because some groups are not represented or not involved in planning and decision making, or because physical or social barriers prevent inclusion of all.

- Nationally adopted community involvement approaches such as CLTSH, WASHCO and WASH clubs can be revised to make community participation more inclusive.

- Changing people’s negative attitudes towards persons with disabilities, women and other marginalised groups requires a range of strategies that include collecting evidence of exclusion, raising awareness of the issues and working with others to effect change.

- There are several organisations that support efforts to change people’s attitudes to excluded groups, including DPOs and organisations that promote women’s empowerment at national, regional and local levels.

- Factors that affect the sustainability of inclusive WASH facilities can be categorised as financial, environmental, institutional, technical and social.

Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) for Study Session 5

Now that you have completed this study session, you can assess how well you have achieved its Learning Outcomes by answering these questions.

SAQ 5.1 (tests Learning Outcome 5.1)

1. A ………………… entails walking through a village to collect information about the community.

2. ………………….. is an approach used in Ethiopia to prevent open defecation.

3. …………….. means taking part or being involved in something, usually a decision or activity.

4. ……………. status is achieved when everyone has access to a latrine and no one defecates in fields or other open spaces.

Answer

1. A transect walk entails walking through a village to collect information about the community.

2. CLTSH is an approach used in Ethiopia to prevent open defecation.

3. Participation means taking part or being involved in something, usually a decision or activity.

4. ODF status is achieved when everyone has access to a latrine and no one defecates in fields or other open spaces.

SAQ 5.2 (tests Learning Outcomes 5.1 and 5.2)

Why do we need to talk about meaningful community participation? What is wrong with existing practices and why are they not inclusive?

Answer

Existing community participation practices usually aim to introduce plans or projects and mobilise the community to contribute to the WASH project implementation. The community is often just expected to listen to what is told to them and/or provide their labour. This cannot be described as meaningful participation and is not inclusive because it does not involve representatives of all sections of the community nor does it involve the community in the planning and decision-making parts of the process. It is also possible that meetings may not be accessible to all and for those who are present, some may not be listened to, nor allowed to speak.

SAQ 5.3 (tests Learning Outcome 5.3)

There is a rural community that believes persons with disabilities live with evil spirits which can be passed on to other people. As a result, persons with disabilities are placed in a secure place out of the sight of other people. Imagine that an NGO is planning a new water project and would like to involve the community in the whole process.

What would you advise the NGO to do to change attitudes and make community participation more inclusive?

Answer

You could advise the NGO to make sure that all community members are fairly represented in the whole process of the project, from start to finish. The NGO could seek out individual people with disabilities, or families with someone who is disabled, or self-help groups or DPOs and work with them to try to convince people in the community that their beliefs about the causes of disability are wrong.

SAQ 5.4 (tests Learning Outcome 5.4)

Which of the following statements are false? In each case, explain why it is incorrect.

- A.Surveyors and planners have all the necessary skills to identify sustainable water sources.

- B.WASHCOs need training, information and support to help them understand their role and responsibilities for inclusive WASH.

- C.All maintenance of inclusive WASH facilities should be organised by the woreda WASH team.

- D.If the whole community understands why inclusion is important and is actively involved in the development of new WASH facilities, it is more likely to be inclusive and sustainable.

Answer

A is false. Specialists such as surveyors and planners should have relevant skills but they may not have the local knowledge that can be very valuable for identifying sustainable water sources.

C is false. The woreda WASH team have an important role to play in maintenance of WASH facilities but they are not solely responsible. Major maintenance tasks may need to be arranged by the regional bureau. Routine preventive maintenance can be undertaken by the WASHCO.