Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 6:16 AM

Unit 2: Vocabulary – old and new

Introduction

Like many other living languages, Scots keeps adapting to modern life and the resulting change has perhaps never been as rapid as in recent years. This unit will introduce you to some of the ways in which Scots has adapted, developed and recycled its vocabulary. The Dictionary of the Scots Language has over 77,000 separate entries. While you may learn some new words during your study it is beyond the scope of this unit to do more than scratch the surface of this rich range of Scots vocabulary.

Yet this unit will hopefully provide a useful introduction to the rich Scots vocabulary. Those who are already confident in using Scots and who are wishing to improve or enhance their Scots vocabulary will find specific activities for more advanced Scots speakers in this unit. They are also directed to explore the links in section 2 and the Further research at the end of this unit.

Important details to take notes on throughout this unit:

- Scots as a living language

- Scots words which have been repurposed for the modern world

- Neologisms in Scots

- The influence of other languages on Scots and of Scots on English.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on any of the four important details we suggested in the Introduction above that you take notes on throughout this unit.

You could write down what you already know about each or any of these four points, as well as any assumptions or questions you might have. You will revisit these initial thoughts again when you come to the end of the unit.

2. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

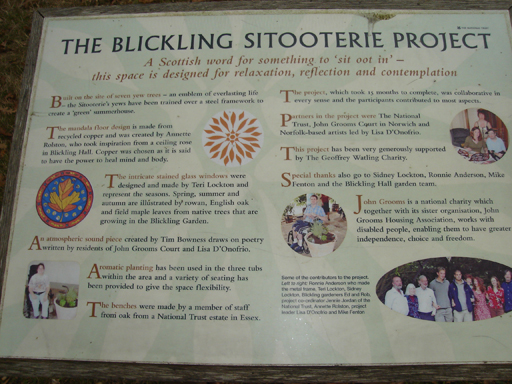

- Sitooterie

- Definition: In a restaurant, etc., an area where patrons can sit outside; a conservatory.

- Example sentence: “Thon’s a braw wee sitooterie ye’v biggit oan tae yer hoose.”

- English translation: “That’s an excellent little conservatory you’ve built on to your house.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Thon’s a braw wee sitooterie ye’v biggit oan tae yer hoose.

Model

Thon’s a braw wee sitooterie ye’v biggit oan tae yer hoose.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Related word:

- Dirl

- Definition: (verb, transitive) To cause to vibrate, to shake.

- Example sentence: “Thon windaes maun dirl in a coorse win.”

- English translation: “Those windows must vibrate in a rough wind.”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Thon windaes maun dirl in a coorse win.

Model

Thon windaes maun dirl in a coorse win.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word.

Activity 4

Part 2

Apart from the meaning of sitooterie, can you identify the meaning of the words Fairnie suggests should be included into the DSL: beamer, riddie, schemie, multi, barrie and bogging?

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 6 items in each list.

beamer

riddie

schemie

multi

barrie

bogging

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.person who behaves, dresses, etc. as if coming from a housing estate

b.a blushing face

c.a high-rise council flat/ block of flats

d.dirty, disgusting, smelly

e.good

f.ready

- 1 = b,

- 2 = f,

- 3 = a,

- 4 = c,

- 5 = e,

- 6 = d

2.1 Finding and sharing vocabulary

In this section you will look at ways in which Scots vocabulary is currently captured and shared online.

The Dictionary of the Scots Language is a free-to-use digital resource which “represents twenty-two volumes of printed text and contains more than eighty thousand full-word entries. Each entry traces the chronological and semantic development of a Scots word, and gives details of orthographic variants, grammatical inflections, derivative words and phrases, and etymological history. The words and terms defined in the DSL are illustrated by quotations drawn from over six thousand sources, covering a wide range of subject areas within Scottish culture and history. Many of the modern Scots words are also illustrated by evidence from oral sources, and include information on phonological and dialectal variation.”

The Scots Dictionary for Schools App is “a free and easy-to-use Scots-English and English-Scots dictionary for use in the classroom or at home. You can use it to browse or search for words in Scots or English and many words feature audio clips so you can listen to their pronunciation.”

There are various social media sites and groups which share and promote Scots vocabulary. Among these are;

On Facebook:

- Scots Language Forum – “a discussion group for speakers of Scots and those interested in Scots language and culture”

- Orkney Reevlers – “a forum for all interested in the Orcadian dialect” (of Scots).

On Twitter:

- @scotslanguage – “Scots Language Centre promoting and supporting the Scots language”

- @DoricDictionary – “Promoting the Doric dialect and the humour of the North East of Scotland”

- @OrkneyWirds – “Orkney Bot o Wirds: wirds fae the Orkney language fower times a day”.

Scotland’s National Centre for Languages (SCILT) has produced a word list which we've made available.

The Scots Language Centre has lists of 100 key words in varieties of Scots.

The Historical Thesaurus of Scots “is a new online resource which aims to categorise the vocabulary of Scots, from the earliest records to the present, according to semantic field. The project is currently in a pilot phase, focusing on selected categories that are rich in Scots vocabulary, such as sports & games, food, and weather.” The thesaurus can be searched in various ways and is useful for a comprehensive list of all the vocabulary in any of the given categories.

Activity 5

Part 2

If you are a user of Facebook and/or Twitter, explore the sites listed in this section to see what discussions are going on among Scots speakers about the way in which they use their language.

2.2 Older Scots vocabulary

This section will draw your attention to the fact that Scots is a living language, with much of its vocabulary, though historic in nature, still in wide use today.

“Scots has been fragmented as a language and, with the dearth of broadcasting in the remaining dialects, very few people have first-hand experience of the spectrum of Scots which is spoken across the country”

A consequence of the ‘fragmentation’ of Scots, mentioned by Billy Kay, is a general tendency to celebrate Scots at a vocabulary level only. Our media regularly runs polls of ‘favourite Scots words’. This is something which everyone can buy into – speakers and non-speakers alike all have a favourite, whatever their position on the use, learning and teaching of the language.

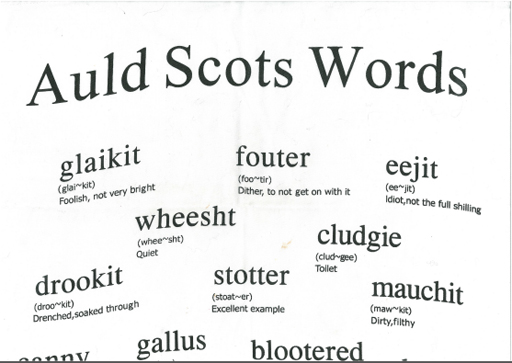

This gives rise to items, such as dishcloths, being offered to tourists and natives alike labelled ‘Auld Scots Words’. In reality, many of the words given and defined on such merchandise are in common, every-day usage, in many parts of the country.

In relation to the use or disuse of particular Scots words Billy Kay explains: “Coming from a fairly strong Scots-speaking area, I presumed that if a word was not used in my own dialect, it would also have become obsolete elsewhere”. If an authority like Kay can make such a presumption, it is perhaps easy to understand others making a similar error.

Scots is still being spoken, its vocabulary being used. The 2011 census identified about 30% of respondents with some skills in Scots. Perhaps surprisingly, for those who see Scots as ‘the language their granny used’, 34.2% of 15-year-olds were reported to have some skills, a figure which rises steadily throughout the age groups to 43.4% of 60 to 64-year-olds, before falling to 36.3% of those aged 85 years and older. Here is a PDF version of the report.

These figures do not support some of the views of Scots reported by the Registrar General for Scotland Scotland’s Census 2011 Release 2A (p. 18), which states a certain lack of understanding of what Scots is.

This lack is illustrated in quotes like these:

“Scots is only what I would consider to be English with a Scottish accent….”

“I wouldn’t know where to put the difference between Scottish dialects of English and Scots.”

“…Who do I consider to speak Scots? Well probably somebody from about 250 years ago.”

On the other hand, the census suggests that large numbers of young, living Scots believe they have some proficiency in the language, which is proof of Scots as a living language in today’s Scotland.

Activity 6

Tuning into spoken Scots

Listen to a short extract from Scots Radio to hear some Scots being used in context. Each podcast includes a range of musical items as well as interviews and discussions.

- a.Start with the first podcast of 2019 and listen to a section of speech. This is a way of ‘tuning into’ spoken Scots. Try to identify:

- i.words you know

- ii.words that sound familiar

- iii.words you might recognise from having studied this course.

- b.To help you understand the podcast, also read the summary of the topics covered underneath the audio recording on the same page.

You might want to note down any vocabulary you want to ‘take away’ to add to your own Scots glossary.

If you want to find out more and maybe train your ear to listen to spoken Scots, there are more episodes on Scots Radio.

2.3 New uses and new vocabulary

In this section you will learn about Scots vocabulary which has been repurposed to meet the needs of the modern world. In addition, you will explore further ways in which contemporary Scots deals with new objects and concepts.

As we have seen, Scots is a living language being spoken by 1.5 million people. There is a belief among some that Scots is dying out due to traditional ways of life and industries dying out and changing. Lewis Grassic Gibbon commented on this process in his 1932 novel Sunset Song:

“Two Chrises there were that fought for her heart and tormented her. You hated the land and the course speak of the folk and learning was brave and fine one day and the next…you wanted the words they’d known and used, forgotten in the far-off youngness of their lives, Scots words to tell to your heart.” (p. 37)

However, Scots has long been repurposed and adapted for modern life. Few Scots speakers who long for lowsin time (the end of the working day, a time when one is lowse - free) have ever worked with plough horses or can have any clear idea that this term was once applied to yoked animals only. It is long since many Scots had to spread their drying washing on walls in summertime, yet the term winterdyke has come to be used for a clothes horse: “…with one mended featherstitch jumper drying /among the nappies on the winterdykes…” (Lochhead, L. Bagpipe Muzak, 1991, p. 55).

Billy Kay reports on the relatively modern use of wappenshaw (weapon-s(c)hawing – a muster exercise), a word which could have been presumed to have become obsolete along with general mustering: “Yet it is a word in common use among the bowling fraternity in the west of Scotland, describing a competition day when one club plays against another.” (Kay, B. Scots: the Mither Tongue, 1986, p. 133).

Modern technology is moving so quickly that language has to change or be created to keep up. Indeed, this process has been ongoing for centuries. In addition to recycling vocabulary for use in new ways, Scots, in common with other languages, invents neologisms. English creates words in various ways and so does Scots.

An example of this in Scots is Sitooterie. The idea of a structure in an ordinary residential building dedicated to sitting out, such as a conservatory or gazebo, is a reasonably modern phenomenon in Scotland. The term was coined and has come to be widely used in Scotland, and beyond (more on which later).

Similarly, the predominance of satellite and cable television has given rise to the term cooncil tele to describe those channels which are free-to-view and the somewhat older corporation juice (tap water).

Activity 7

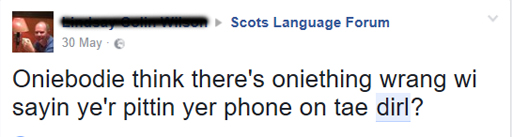

The word dirl is a good example of a word which has come to have new uses. As you have seen in the DSL, it is widely used as both a verb and a noun and has several meanings. Its entries were supplemented in 1976 and 2005. Recently, the following was posted on the Scots Language forum’s Facebook page discussing a modern use of the word dirl.

- Translate this post, paying close attention to the last word and the modern twist to its use.

Answer

Here is our translation of the post:

Anybody think there’s anything wrong with saying you’re putting your phone on to vibrate?

Please note:

This translation relates to the definition 2.(1) given in the DSL for dirl as an intransitive verb: Implying sound, motion or both: to vibrate, shake, rattle, reverberate; to emit a ringing sound when struck.

2.4 Links to other languages

In this section you will consider ways in which Scots has been influenced by other languages and, has in turn, influenced English.

As sister languages, Scots and English share a great deal of vocabulary. A common criticism levelled against Scots is that it has no words for modern devices, such as ‘television’. The fact is, however, that it shares such vocabulary with English.

And ‘television’ can be seen as not being English either, coming as it does from the Greek tele- (far) and the Latin vision (seeing). Many other European languages have adopted a similar term:

| Language | Word for ‘television’ |

|---|---|

| Albanian | television |

| Estonian | television |

| French | télévision |

| Italian | television |

| Polish | telewizja |

| Spanish | televisión |

The fact that Scots uses the same word is not, in fact, remarkable then. More remarkable are the languages like German (Fernsehen) which do not adopt the word in the same way.

Scots is also a Germanic language. This can be clearly seen in words such as ken (know), which is limited to certain uses in English (e.g. “to be beyond your ken”), but is very close to the German kennen. Similarly, the Scots and German for ‘light’ are identical – licht.

Scots-speaking travellers to Oslo, and other Scandinavian destinations, will have little trouble reading signs such as the one below:

With the Scots words oot (out) equating to Norweigan ut (Swedish ute and Danish ud) and gang (go) to gang, this seems an entirely logical name for an exit. And those who watch Scandi-crime drama are thrilled to hear how bra (good) everything is in Swedish or Norwegian: braw in Scots (albeit with slightly differing pronunciations). Scots was influenced by Norse languages, due to Viking invasion and settlement, although the languages are all Germanic and these words can trace their roots back that way.

Dutch and Scots share certain words too. A Scots-speaking person might redd (tidy, clear) a room, with the Dutch equivalent being reden. To redd has become an important community activity, which is illustrated by the Shetland Amenity Trust website page on “Da Voar Redd up” which is the UK’s most successful community litter pick!

The Scots word keek (to glance or look sharply) also has a Dutch cognate in kijken. Again, these are both Germanic languages, making links understandable. However, trade links between Scotland and Dutch and Flemish speaking nations strengthened language links too.

France and Scotland formed the Auld Alliance for centuries, and this had a similar influence on trade and language. The Scots dinnae fash yersel (don’t worry, don’t get upset) has roots in the French fâcher (to annoy). The large plate – ashet – found in Scotland (and interestingly New Zealand), is linked to the French assiette.

Latin gave birth to the Romance languages but also had a more direct influence on Scots vocabulary. Many Scots legal terms came straight from Latin, for example ‘procurator fiscal’. Schools too have their share of Scots vocabulary from Latin: where would any school be without the jannie, the diminutive of ‘janitor’? This word for a caretaker made it straight from the Latin into Scots.

Gaelic has given many words to Scots, notably for geographical terms: glen, loch, strath and clachan, which have often become part of place names, as well as specific terms such as ceilidh and skean dhu which form part of Scots and English by virtue of being the best terms for ‘cultural’ nouns.

There is a wide-spread belief that Scots is being corrupted by English in modern times. The influence of the mass media and the internet are blamed for this phenomenon, which is not unique to Scots. Famously, the Académie Française tries to prevent Anglicisation of French. While Modern Scots speakers tend to use English vocabulary at need to supplement their Scots, English has always borrowed words from Scots too.

This includes terms such as blackmail, which originated in the borders in the days of the Reivers; and more positively, cosy and gumption, both originating in 18th Century Scots. A more recent word found in English from Scots is minging, the Scots word mingin, Anglicised by the addition of the characteristic final g.

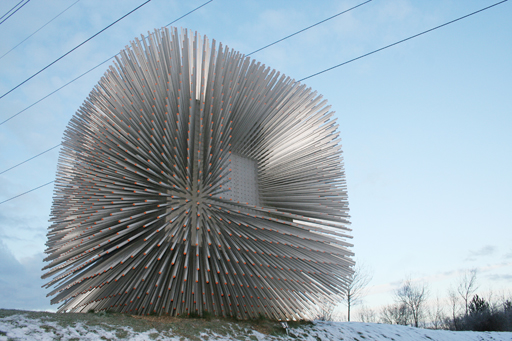

But what of Sitooterie? Here is a picture of Sitooterie II, Barnards Farm, West Horndon, Essex:

This Sitooterie at Barnards Farm was commissioned as “a permanent pavilion to sit within their grounds…The cube was precision-machined, by an aerospace company, from 15mm anodised aluminium and bonded together using special high-strength adhesive…Seating is created by elements that extend into the cube to support a machined aluminium surface”.

Similarly, Blickling Hall Garden, north of Aylsham in Norfolk, displays the following example of the English language borrowing from Scots:

Scots has borrowed widely from other languages, but continues to exert its own influence on English, as it has done for centuries, to this day. As J Derrick McClure says:

“What this abundant, varied and productive foreign influence should show is that Scots was once the language of a cosmopolitan, adventurous, outward-looking people, whose country, small and isolated though it was, played a full part in the economic, political and artistic life of Europe.”

And finally, accent plays a big part in the spelling of Scots, which is a non-standardised language. This can be seen in the various spellings of dirl; dir(r)le; dirrel – as well as many other Scots words.

The section on Grammar in part two of this course will look more particularly at the peculiarities of Scots grammar, such as the use of thon in our opening sentence Thon’s a braw wee sitooterie ye’v biggit oan tae yer hoose.

And in the unit on Dialect diversity in part one of the course you will explore regional variations of Scots in detail, which is another key reason for spelling variations of Scots words.

2.5 What I have learned

The final activity of this section is designed to help you review, consolidate and reflect on what you have learned in this unit. You will revisit the key learning points of the unit and the initial thoughts you noted down before commencing your study of it.

Activity 8

Before finishing your work on this unit, please look below at what you wrote in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- Scots as a living language

- Scots words which have been repurposed for the modern world

- Neologisms in Scots

- The influence of other languages on Scots and of Scots on English.

Further research

The Historical Thesaurus of Scots:

This project, in its pilot phase, uses the data in the DSL and aims to create a full historical guide to Scots vocabulary, using the Historical Thesaurus of English as its model. It already provides a valuable tool for those wishing to explore Scots vocabulary in some depth.

The Scots origins of place names in Britain:

This resource from GetOutside by Ordnance Survey provides a brief overview of the language along with a comprehensive e-book, detailing and listing the elements of place names which have been derived from Scots. There are other versions on the site for Gaelic, Scandinavian and Welsh languages. Of great interest to those wishing to understand local and national geography and history.

St Andrews Institute of Scottish Historical Research:

This blog-post gives an overview of Chris Robinson’s work on The Flemish Influence on Scottish Language as well as some interesting insights into the difficulties in tracing with certainty the origins of Scots words. It also includes references for further reading.

SCILT Passeport pour la Francophonie:

Containing content migrated from Education Scotland this resource gives detail for learners on the ancient links between Scots and French as well as some activities to explore Scots.

Scots Language Centre: The Scots Language and Its European Roots:

This is an edited summary of a lecture by Dr Sheila Douglas at Robert Gordon’s University. It gives an overview of the links between Scots and other languages as well as providing a bibliography for further study.

Lallans 12 (1979): Guid Scots – gutes Deutsch:

This paper by WRW Gardner explores the links between Scots and German more fully.

Project Gutenburg: Scandinavian influence on Southern Lowland Scotch by Geogre T Flom:

This, admittedly rather old, piece of research examines the links between Scots and Scandinavian languages in more detail, attempting to list all the loan words, and their origins.

Now go on to Unit 3: Scots in education.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Course Image: Supplied by Bruce Eunson / Education Scotland

Image in Activity 2: Literatirus. This file is licensed in the Public Domain

Image in Activity 3: Archives New Zealand. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Image Section 2.2: Diane Anderson

Image in Activity 7: Scots Language forum. Found on Facebook.

Image of signs in section 2.4: Punkmorten. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Image of Sitooterie in Section 2.4: oneblackline. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Image of Sitooterie poster in section 2.4: The Sitooterie project interpretation board at Blickling Hall garden. Northmetpit. This file has been released into the public domain.