Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 9:48 PM

Unit 4: Dialect diversity

Introduction

In this unit you will learn about dialect diversity within Scots language. Like many languages, Scots is spoken and written in a variety of regional dialects. This unit will introduce you to these dialects and discuss some of the differences that appear between them.

The predominance, and history of, the dialects of Scots language are particularly important when studying and understanding Scots due to the fact that the language is presently without an acknowledged written standard. Whilst there are differences between the regional dialects, they are also tied together by common features and similarities.

Important details to take notes on throughout this unit:

- The number of Scots language dialects commonly recognised as being used in Scotland today

- The present state of Scots language

- The regard which regional speakers of Scots have for “their” dialect

- The influence of Norn (a North Germanic language belonging to the same group as Norwegian) on Scots language and the different dialects today

- The census of Scotland in March 2011, which asked for the first time in its history whether people could speak, read, write or understand Scots.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on any of the five important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit.

You could write down what you already know about each/any of these five points, as well as any assumption or question you might have. You will revisit these initial thoughts again when you come to the end of the unit.

4. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

- Kist

- Definition: A chest, box, trunk, coffer, esp. a (farm-)servant's trunk.

- Example sentence: “We had ta howk a muckle hole ta bury the kist ithin...”

- English translation: “We had to dig a big hole to bury the box in...”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

We had ta howk a muckle hole ta bury the kist ithin.

Model

We had ta howk a muckle hole ta bury the kist ithin.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Language links

Please note that the word kist is another example of the close links the Scots language has with other European languages. In this case, it is the German language. The German language has the word die Kiste, which means a box made of sturdy materials, very often wood.

A Kiste is an object that often has a way of securing the lid in order to lock it. It was derived from the Latin cista – Kiste and introduced into the German language in the 12th century.

Related word:

- Howk

- Definition: 1. To dig, delve the soil.

- Example sentence: He made a pit an howkit deep.

- English translation: He made a pit and dug deep.

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

He made a pit an howkit deep.

Model

He made a pit an howkit deep.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

4.1 The Scots dialect of the Shetland Isles

The text below will tell you about the history of Shetland, looking specifically at this one dialect of Scots, and the details which have shaped the linguistic features of the Isles.

The related activities will assist you in developing your knowledge of dialect diversity and understanding of Scots language. Learning about the dialect of Scots spoken in the Shetland Isles is also important for understanding the influence of Norn on Scots language.

Activity 4

Search the online Dictionary of the Scots Language (DSL) for the two words quoted in section 1, kist and howk. Because of the dialect diversity present in Scotland, the DSL lists where Scots words have been used and spelled differently in different parts of the country.

- a.Read the quotations in the DSL for howk. Find the reference for Shetland indicated by the abbreviation (Sh.) and note it in the textbox along with the translation.

- b.Then list other spellings of howk and note down the regional dialect or area where this spelling was found. What changes in the different spellings?

Answer

a.hock, hok(k) (Sh.);

Sh. 1888 B. R. Anderson, Broken Lights. “He made a pit, an' hockit deep.”

English translation: “He made a pit, and dug deep.”

b.hoke – Wigtown

houck – Edinburgh

howck – Ayr

hock, hok(k) – Shetland

hauk – Orkney

huck – Glasgow

The vowel changes from monophthong hoke [hok] to the diphthong hauk [hʌuk].

The length of the vowel changes as well from the short hock/kk [hɔk] to the longer hoke [hok].

It is interesting to see that in the very south and north of Scotland the vowel in howk is pronounced as a monophthong, whereas in more central areas of Scotland it is pronounced as a diphthong.

Language links

Scots, like all other languages, has a number of different dialects. These can be distinguished by different sounds and pronunciation of words as well as different vocabulary and sometimes even grammar.

For example, the German language, which is historically closely related to Scots, has a wide range of dialects from the Franken and Schwabian German in the South to Plattdeutsch in the North. People from these areas often have to revert to speaking standard German to be able to understand each other. These dialects are mostly spoken and hardly ever appear in printed form.

The difference between Scots and German is that German has a mutually agreed standard form, Hochdeutsch, which is the standard in written communication in Germany, whereas Scots mainly exists in the form of dialects and does not have an officially accepted standard.

4.2 Dialects of Scots in today’s Scotland

This section will draw your attention to the different dialects within the Scots language and their role and meaning for the speakers of these dialects. Over 30 years ago, prominent Scots activist and acknowledged authority on the language, Billy Kay, wrote,

“the myth that Scots is only intelligible within a short radius and that one dialect speaker cannot communicate with another one from a different area has also resulted in a reduction in the use of Scots and a reinforcing of the local rather than the national identity with the tongue.

I have heard many Scots-speakers say that they are only comfortable talking Scots to someone from the same locality. With everyone conditioned to some extent by official disdain for the tongue, it takes a strong person to speak Scots in a formal situation where people may classify them according to one or other stereotype as coarse or uneducated...”

Kay’s comments are as true today as they were then. Despite recent developments, such as the Scottish Government launching a Scots Language Policy in 2015, the years of low status afforded to Scots at a national level, are one reason why in some areas of Scotland an increased feeling of pride has developed for the various regional dialects of Scots.

An essential lesson in learning about Scots language is that the top 2 local authority areas for percentage of Scots speakers identified in the 2011 Census, Shetland and Aberdeenshire, are both places where the Scots speakers are not in the habit of describing themselves as “Scots” speakers – but as speakers of “Shetland dialect” and “Doric” respectively.

This section will describe and discuss some of the factors for how, and why, this is the case.

Activity 5

In this activity you will learn about the 10 dialects of Scots that are considered the ‘main’ dialects.

First of all, study the map of Scotland below and try to work out which are the different areas of dialect.

Now drag the names of the dialects to their correct position on the map.

Discussion

Please note: In some categorisations, Ulster Scots is added to the listings of Scots dialects. It is spoken primarily by the descendants of Scottish settlers in the regions of Ulster, and particularly counties Antrim, Down and Donegal in Northern Ireland. This dialect is also known as ‘Ullans’.

The dialect Southern Scots is also known as the ‘border tongue’ or ‘border Scots’ as it is spoken in the areas near the border to England. In addition, some make a distinction between the dialects spoken in rural and in urban areas.

Consequently, a new Scots dialect category has been defined by Robinson and Crawford, the ‘Scotspeak’, which refers to the modern variants of the Scots spoken in Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow (Robinson & Crawford, 2001).

The complexities of defining a dialect of the Scots language are outlined in this useful categorisation published on the Scots Language Centre website.

Scots is the collective name for Scottish dialects known also as ‘Doric’, ‘Lallans’ and ‘Scotch’ or by more local names such as ‘Buchan’, ‘Dundonian’, ‘Glesca’ or ‘Shetland’. Taken altogether, Scottish dialects are called the Scots language.

The Scots language, within Scotland, consists of four main dialects known by the names (1) Insular, (2) Northern, (3) Central, and (4) Southern. These dialect regions were first defined and mapped in the 1870's. The sub-dialects exist because people who belong to a main dialect also have ways of speaking, such as words, phrases, or pronunciations, which are only found in a smaller area within a main dialect. And even within sub-dialects, it is also possible to find forms of speech used in very localalised areas, such as particular towns and cities.

So, to give one example, Central Scots, which is a main dialect, has a sub-dialect called West Central Scots, and within West Central Scots the city of Glasgow has long had a distinct city dialect. This means that people who speak Glasgow city dialect are speaking a form of West Central Scots and also belong to the wider Central Scots region because they share many features with other speakers in that larger dialect region.

We can then take this one step further, onto a national scale, and say that people speaking Glasgow city dialect are Scots speakers because Central Scots is one of the main dialects of the Scots language as a whole.

Activity 6

Now would be a good time to note and develop your own thoughts on the Scots language and its dialects.

You may have personal experience, as either a Scots speaker, or as a speaker of a dialect of another language, which can help to frame your thoughts.

Or there may be examples online which can help to build your knowledge.

For example, consider and take notes on the following:

- Do you think that the fact that Scots is mainly a spoken language has an impact on its standing and recognition as ‘a language’?

- When Scots language is used in mainstream contexts, is it for a particular effect beyond simply representing the speaker(s)? Compare this for example with Swiss German. This is a spoken language only, but a language used by people from all social groups. It is even spoken in the parliament of the German-speaking part of Switzerland.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your own answer might be different.

Many Scottish people tell the story of how the film Trainspotting was subtitled in other countries – even in countries like America where English is spoken as a first language. Does that say more about Scots and its distinctiveness from English, or more about audiences and perceptions of “proper” English?

The Pixar film Brave featured a distinctly Doric speaking character who was not subtitled, but you can tell the character is supposed to be difficult to understand to suit comic purposes.

Even within Scotland where there are 1.5 million Scots speakers, dialect diversity and a distinctive voice can be divisive in terms of whether speaking with a strong accent means one will not be understood by others.

This news article from the Shetland News reports on one such controversy, where the actor Brian Cox had to re-record his lines and tone down the dialect he was speaking in a BBC series.

4.3 A brief history of the Shetland dialect

In this section, you are going to focus on the Shetland dialect as an example of a distinct dialect of Scots. You will learn about the history of the dialect and how aspects of this history can still be recognised in the dialect today.

Activity 7

- As you read the text on the Shetland dialect, make notes in the form of bullet points on what you consider to be the key aspects of the history of the Shetland dialect.

Here is an example:

- A now extinct language called Norn was once spoken in Shetland, Orkney and Caithness.Shetlanders kept speaking Norn longer than the people in Orkney and Caithness.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your choice of aspects might be different.

- transition to Scots was quicker in Orkney and Caithness than in Shetland, due to their closer proximity to the Scottish mainland

- transition from Norn to Scots was made all the easier due to Scots already containing many Scandinavian borrowings

- Shetlanders cultivated a bilingualism which enabled them to communicate on two levels with the dialect considered to be on the lower level

- Scots spoken in Shetland today is heavily Anglicized due to popularity of American TV and culture, increased mobility of people, together with the increasing influence of the internet

- today the Shetland dialect is spoken far less than ever before

- in the 2011 census Shetland dialect had highest percentage of speakers across the whole of Scotland, tied first with Aberdeenshire

- being able to speak good English trumped the ability to speak good Scots - no small part due to the role played by English as the language of education

- Scots speakers who can also speak English are bilingual but are neither viewed by other Scots, nor by themselves, as bilingual.

The dialect of Scots spoken in the Shetland Isles has been strongly influenced by Norse, Scots and English. Each of the three languages has influenced the linguistic features of the islands over their history as each of the three respective nations have dominated the Shetland Isles at different times.

From around the 9th century to the 17th, the people of Shetland spoke Norn – a North Germanic language belonging to the same group as Norwegian. Norn is now extinct, but was once spoken in Shetland, Orkney and Caithness.

The transition to Scots was quicker in Orkney and Caithness than in Shetland due to their closer proximity to the Scottish mainland. It then accelerated in 1468–69 when Shetland and Orkney were pledged to Scotland by the Danish as the dowry of Princess Margaret of Denmark when she married King James III of Scotland.

Whilst Shetlanders took longer than their southern neighbours to gradually move from speaking Norn to Scots it is not surprising that they eventually did. Once the Northern Isles were officially part of Scotland, the influence of law and religion in particular began to impact the previously Scandinavian culture of Shetland.

The Scots language, which was increasing in use, was itself being influenced by English as written Scots began to be modified to resemble English in more and more ways. The transition from Norn to Scots was made all the easier due to Scots already containing many Scandinavian borrowings, such as:

| O.N | kima | Sc. kirn | Eng. churn |

| O.N | byggja | Sc. bigg | Eng. to build |

| O.N | hepti | Sc. heft | Eng. handle |

| O.N* | illr | Sc.** ill | Eng.*** bad |

Footnotes

*O.N. = Old NorseFootnotes

** Sc. = ScotsFootnotes

*** Eng. = English

John J. Graham wrote in the Introduction to his word book, The Shetland Dictionary,

“a mother tongue is not easily eradicated [...] Shetlanders cultivated a bilingualism which enabled them to communicate on two levels, although in social terms there was no question but that the dialect was on the lower level. While the use of English to strangers was justified ostensibly as ‘good manners’ this custom was undoubtedly a tacit recognition of the socially inferior role to which the dialect had been relegated.”

The Scots spoken in Shetland today is heavily Anglicized – just as with the rest of Scotland – due to the globalization of English. Popularity of American TV and culture, increased mobility of people, together with the increasing influence of the internet, means many people believe we are now at a linguistic point in time where Shetland dialect is spoken far less than ever before.

Having said that, the data gathered in the 2011 Scottish census showed 49% of people living in Shetland identified themselves as Scots speakers. This was the highest percentage across the whole of Scotland, tied first with Aberdeenshire.

Whilst there is substantial evidence that Shetlanders have a great passion for their local dialect (exemplified by the volunteer-run dialect promotion group based on the Isles: Shetland ForWirds) it has been the case for many decades that being able to speak good English trumped the ability to speak good Scots – the same situation exists today as described by Graham when writing in 1979 (p. xvi).

This is in no small part due to the role played by English as the language of education. At the same time, it highlights an important point not only for this unit, but of this entire course: that Scots speakers who can also speak English are bilingual but are neither viewed by other Scots, nor by themselves, as bilingual.

Activity 8

Now go over your notes what you have learned about Scots dialects in this unit so far.

Write a paragraph of about 50 to 100 words summarizing the key things you have learned about dialect diversity in Scotland. Then reveal our model answer and compare it with your own.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

Speakers in Shetland, Orkney, Caithness and the North East (the four furthest North of the ten dialects) tend to view their dialect as distinct from Scots. Whereas those within the next six (covering the central belt and southern areas of Scotland) will generally consider themselves as Scots speakers.

At an academic level, researchers studying Scots for linguistic purposes will often isolate one particular dialect or geographical area from another, as there can be vocabulary and features of grammar that are unique to that one dialect or region.

4.4 Dialect diversity and bilingualism

Dialect diversity is important in understanding why almost no Scots speaker considers themselves to be bilingual – certainly not in the way a speaker of English and German, or English and French is classed as being bilingual.

Scots went for centuries as being a language which should only be used in the home, as a language of the streets, even considered by some to be nothing more than slang and simply bad English. Although this was – and often still is – a common perception, the language continued to be spoken, and in certain regions, was spoken a great deal. Within the regions, speakers were – and, again, often still are – in the habit of labelling the language as “their” local dialect.

Attitudes towards the language, even amongst many of its champions, rarely sought to unite the regions, instead preferred to maintain within its quarters and boundaries. Modern day Scotland is not a place where being a speaker of English and a speaker of a local dialect offers individuals the tag of being bilingual.

The child who grows up with a Scottish father and a Norwegian mother - learning English and Norwegian from birth - is viewed as bilingual and different from the child who grows up speaking both English and Scots, regardless of whether they learned their Scots from one of their parents, from the community, or whether they learned their English at home or at school.

An interesting linguistic example, common across Scotland today, is the child who was born in Scotland after their parents emigrated from Poland. This child often grows up learning Scots in the community, along with learning Polish at home and English at nursery and school. The value of each of these three languages changes in different social situations, and each language has a value, but the child is rarely viewed as being trilingual. Instead only their aptitude for English and Polish is valued and/or acknowledged within Scotland.

Activity 9

In this activity you will further explore the concept that speakers of a Scots dialect as well as English (or another language) should be considered bilingual.

Part 2

In this part of the activity you will take a closer look at the links between speaking a dialect and being bilingual. Read the text Scots dialects 'as good as a second language'.

After reading it, decide whether the statements below are True or False according to the BBC News text by Ken Macdonald.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

b.

The correct answer is false. It takes longer to switch back into the dominant language.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is b.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

4.5 The 2011 Census

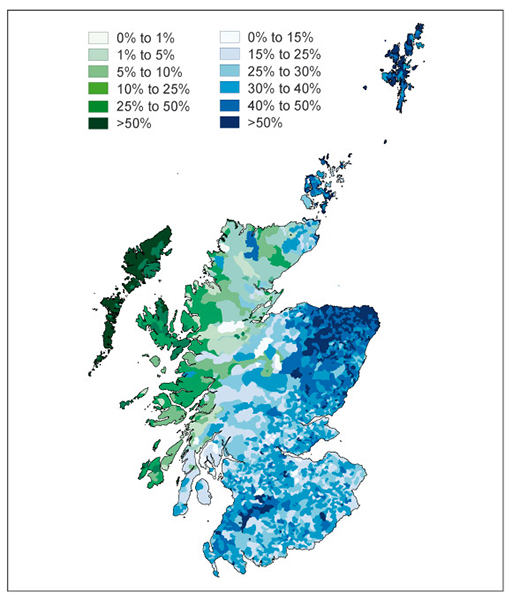

In March 2011 the census of Scotland asked for the first time in its history whether people could speak, read, write or understand Scots. At the time, the population of Scotland was 5,295,403.

The figures for the most Scots speaking regions according to the answers given by people who filled in the survey may be broken down into the ‘biggest single figures’, and the ‘biggest percentages’ as part of the regional council population.

| Biggest single figures | Biggest percentages of regional council population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Glasgow City Council Region: | 142,111 | Aberdeenshire Council Region: | 49% |

| Fife Council Region: | 123,205 | Shetland Council Region: | 49% |

| Aberdeenshire Council Region: | 119,078 | Moray Council Region: | 45% |

Whilst 49% of Shetland residents responded to the 2011 Census confirming they spoke Scots, the population of Shetland at the time of the census was only 22,400.

The Biggest Single Figures recorded for Glasgow and Fife greatly exceed the Single Figures and the populations of places such as Shetland and Orkney.

Glasgow and Fife are both part of the dialect region commonly referred to as Central Scots.

(Scotland's Census,Census Results, 2011)

As discussed in the previous section 4.3, Insular Scots can be divided into Shetlandic and Orcadian, and both have been studied in depth by the likes of Jakob Jakobsen and Hugh Marwick – both men publishing respected works on the linguistic features found within the Northern Isles of Scotland.

As you learned in section 4.2, the dialect of Central Scots can be broken down further as West Central, South Central, East Central South and East Central North as each area has a few linguistic features unique to their region.

In Scots language circles it was a proud moment for places such as Orkney, Shetland and Moray to be recognised as having every second resident recognised as a Scots speaker, and in a similar way as Glaswegian and West Central Scots have.

“… enormous internal prestige. The strength of the dialect there lies with the strength of the working-class identity which is basic to people from the Western industrial belt. In addition, by means of the media working-class heroes such as footballers or comedians have given Glaswegian ‘underground’ prestige in the rest of Scotland, so that its influence is extending well beyond Glasgow”.

What becomes clear across all of Scotland are the passion and feelings of pride that exist across the country for the Scots language. But, due to social and cultural factors that had an impact throughout centuries, there is still a need to identify, understand and respect the dialect diversity which exists.

An individual wishing to learn Scots language would, rather than learning a standard language, encounter dialect diversity across the country, with linguistic features relating to vocabulary and grammar changing within the areas of Scotland identified above.

Whilst recognition of this element of Scots language is essential to properly grasp the sense of identity Scots speakers from different parts of Scotland have, the over-emphasis placed by Scots speakers on the diversity aspect of the language is one of the reasons for the division that keeps Scots language from truly uniting as a language with a community of 1.5 million speakers, and may hinder the chances of the figure rising in the future.

The reason for this over-emphasis could be due to the different history of the dialects spoken in Shetland, Orkney and Caithness within Insular Scots, in comparison to the history of the Glasgow or Fife dialects within Central Scots.

Or, it could be the more recently formed social perceptions of “rural” and “broad” Scots spoken in Aberdeenshire or the Borders versus the streets of Dundee or Leith.

Either way, the content of this Dialect diversity unit is important for achieving an accurate understanding of what the language is today, and where it has been in the past across Scotland.

Activity 10

In this section you have elaborated further upon the points discussed in the previous sections on Shetland – this time with reference to Glaswegian, the Central Scots dialects of Lowland Scotland and the 2011 Census.

- a.After reading the text in this section, note points which are of interest to you for reflection at the end, such as:

- 2011 was the first time a question on Scots had been included in the Census

- Glasgow and Fife are both part of the dialect group Central Scots

- b.At the end of this activity compare your notes with what you wrote in Activity 1.

Further research

Elaine C Smith and regional variations of the Scots language

Elaine C Smith talks about the different dialects and words she encountered during her Glaswegian upbringing, her teaching career in Edinburgh and her panto performances in Aberdeen. She comments on the regional variations from the Borders to the North East. Elaine's favourite word is 'dreich ' but she enjoys the liveliness of Scots language in everyday speech.

The Scots Language Centre is an online resource with the purpose of promoting Scots. The quote used in section 4.2 to define the various regional dialects of Scots is from the Scots Language Centre.

Shetland ForWirds is a volunteer-run organisation based in Shetland. Their website contains a wealth of information on Shetland dialect, including an online version of John J Graham’s The Shetland Dictionary which is mentioned above.

As in Shetland, Orkney has many volunteers who strive to share the language used in their isles. The Orkney Dictionary website centres around Margaret Flaws and Gregor Lamb’s Orkney Wordbook which is the essential text for understanding the Orcadian dialect.

NRS is a non-ministerial department of the Scottish Government. Their purpose is to collect, preserve and produce information about Scotland’s people and history and make it available to inform current and future generations. All information discussed above relating to the question on Scots language in the 2011 Census can be found on the NRS site.

How bilingual brains switch between languages

This article will provide information on what actually happens in our brain when we switch between languages. This will help you explore the bilingualism and ‘switch-cost’ concepts from section 4.3 further (Devitt-NYU, J. (2018) ‘How bilingual brains switch between languages’, Futurity, 11 September 2018).

This is the website of the research and information centre for bilingualism and language learning based at the University of Edinburgh.

Thomas Bak on the Metis Owris project team

Explore the work of Thomas Bak, a neuroscientist based at the University of Edinburgh, whose research explores the positive effects of bi- and multilingualism on the human brain.

Now go on to Unit 5: Scots Language in Politics.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Course Image: Supplied by Bruce Eunson / Education Scotland

Activity 2 Image: © Andrew Bowden, This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license

Activity 3 Image: Gardening: a man digging in a walled garden. Wood engraving. Credit: Wellcome Collection. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Section 4.3 image: Courtesy of Mrs Beryl Graham

Section 4.4 image: "Vernacular" by shirokazan. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Section 4.5 Map: Adapted from The Scots Haunbuik

Text

Extracts in Activity 5: Scots Language Centre, https://www.scotslanguage.com/articles/node/id/69 Used with permission