Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 27 February 2026, 9:25 PM

Unit 5: Scots Language in Politics

Introduction

As you have learned in previous units, due to a range of historical and social factors, Scots has been, and in a number of cases still is, viewed as corrupt or poor English, and does not tend to be used in more formal or official settings. In this context, it is perhaps unsurprising to learn that the presence and use of Scots in political proceedings is limited. However, it is not entirely absent.

In this unit you will learn about its usage and status in the course of parliamentary business in both the Scottish and UK Parliaments. As well as learning about how Scots is used in politics, you will also learn about different political approaches towards Scots.

This unit will introduce you to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, and set out the policies adopted towards Scots by the different Scottish Executives/Governments since 1999. The policy positions of the three main Scottish political parties (Scottish National Party [SNP], Labour and Conservative) will also be considered.

During the course of this unit, interesting questions will be raised about the marked difference in status between Scots and Gaelic, as well as the position of Scots in relation to political nationalism and unionism.

Important details to take notes on throughout this unit:

Different legislation for Scots and for Gaelic in Scotland

Instances where Scots has been used in both the UK parliament and the Scottish Parliament

The different approaches taken by the different political parties in Scotland

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the three important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these three points, as well as any assumption or question you might have. You will revisit these initial thoughts again when you come to the end of the unit.

5. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: An uproar, commotion, hubbub, disturbance, a broil, squabble, row.

- Example sentence: “Noo dinnae turn a wee stooshie intae a stramash...”

- English translation: “Now don’t turn a little squabble into an uproar...”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Noo dinnae turn a wee stooshie intae a stramash...

Model

Noo dinnae turn a wee stooshie intae a stramash...

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Related word:

- Muckle

- Definition: Of size or bulk: large, big, great.

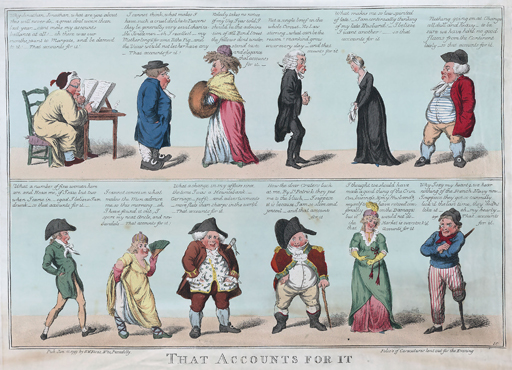

- Example sentence: Ah cannae believe the size o the grate muckle men in thae cartoon.

- English translation: I can’t believe the size of the great big men in that cartoon.

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Ah cannae believe the size o the grate muckle men in thae cartoon.

Model

Ah cannae believe the size o the grate muckle men in thae cartoon.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

5.1 How Scots is used in politics

The Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body (SPCB) is responsible for (amongst other things) developing the Language Policy of the Scottish Parliament. It is a statutory body made up of five members – the Presiding Officer, who chairs the Body, and four Members elected by the Scottish Parliament (MSP). Members are elected as individuals to represent the interests of all the MSPs and not as party representatives.

Who decides what languages are used?

The Scottish Parliament

The working language of the Scottish Parliament is English and the Scottish Parliament legislates in English only. If a Bill is translated into a language other than English, the English language version will always be the authoritative version. With the prior agreement of the Presiding Officer, MSPs may use any language in parliamentary debates. In committee meetings, the prior agreement of the convener should be sought.

Proposals for bills, motions, amendments and questions must be in English, but may be accompanied by a translation in another language provided by the MSP. When such a translation is provided, it will be published in the Business Bulletin along with the English text of the proposal, motion, amendment or question.

Gaelic has special status in the Scottish Parliament under the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005. There is no equivalent Act for Scots. This distinction is clear in the SPBC Language Policy 2013-18, which states that:

The SPCB’s Gaelic Language Plan 2013-18, required under The Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005, seeks to give effect to the principle that the Gaelic and English languages should be accorded equal respect. The SPCB, for historical and cultural reasons, also recognises the use of Scots.

This commitment is continued in the 3rd edition of the SPBC Gaelic Language Plan. However, the documentation in the 3rd edition document, which includes details about the consultation for the 3rd edition, states that ‘[s]everal respondents welcomed the plan and also stated that the Parliament should make more provision for Scots too’, which highlights a marked awareness of the different treatment of both languages (Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body, 2018, p. 47).

Parliamentary signage features only English and Gaelic. Similarly, parliamentary literature - such as the ‘Fact Sheets’ located in the public area of the Scottish Parliament, which explain to visitors and the public how aspects of the Parliament work - are not provided in Scots (though are available in English and Gaelic, as well as a range of other languages including German, French, and Chinese). Gaelic is also treated differently in the Official Report, as you will learn about below.

Activity 4

You just learned that different languages are used for different publications and communications in the Scottish Parliament. Do you think the use of particular languages in a parliament building is significant? Why? Take a note of your response, then compare it with our model answer.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

I think that many people might believe that the use of particular languages in a parliament building is important, because the use of a language in a parliament building shows respect towards that language. Particularly when it is an indigenous language to that country. It assists in raising the status of the language within the minds of the population.

The UK Parliament

English is the language of proceedings in the House of Commons - as determined by the Procedures Committee. English alone may be used in the Chamber. However, there are moves underway to allow Welsh to be spoken in the Chamber during proceedings of the Welsh Grand Committee as outlined in this BBC News article.

As a result of The Welsh Language Act 1993, Welsh can already be used in limited circumstances outside of the Chamber. No other languages have any special status in the UK Government. The UK Government stated the following in response to a report on the use of the Welsh language in the Welsh Grand Committee:

The status provided by the Welsh Language Act 1993 is unique within the United Kingdom. It is this status that forms the basis of the derogation for the use of the Welsh language in particular circumstances in the House of Commons. As there are no other languages with a similar status in statute, we do not perceive there to be a case for a similar derogation to apply to other languages.

In the actual report, the UK Government stated that they ‘detect no calls for the use of other minority languages in parliamentary proceedings', (UK Parliament, 2016).

Similarly, a report of the Procedure Committee published in December 2016 stated that ‘the Committee notes the unique status of the Welsh language in the United Kingdom [and …] detects no demand for the use of languages other than English or Welsh in Parliamentary proceedings at Westminster’, (UK Parliament, 2016).

Discrepancies in the status of the UK’s indigenous languages

Considering the timing of the parliamentary publications above, it is interesting to contemplate why the other two languages in the UK, Gaelic and Scots, which had been granted the status of indigenous languages in 2005 and 2015 respectively, were not included in the report and its recommendations.

Why do you think Welsh was considered to have a ‘unique status’? Could it be related to the way in which Welsh was and is used in Wales? Could the ‘image’ of an indigenous language play a part in such decisions? Does the number of speakers of such language matter here, or is it important to what extent the language is used in written communication?

Please note that the strong political dimension of the use of indigenous languages can for example be observed in current discussions in Northern Ireland around the role and official status of Ulster Scots and Irish.

5.2 Oath making and affirmation taking in Scots

Oath making and affirmation taking is conducted differently in the Scottish Parliament and the UK Parliament. At the swearing-in ceremony that takes place at the beginning of a new session of the Scottish Parliament, some MSPs choose to take their oath or solemn affirmation in Scots as well as English.

The Scots Language Centre website reports that in May 2016, ‘four members repeated their oath or solemn affirmation in the Scots dialect of Doric, and one member repeated it in general Scots’ .

Activity 5

Scottish indigenous language in the EU Parliament

Following your consideration of the status of Welsh in the UK Government, here is another example of how recognition by political bodies helps raise the status of an indigenous language, in this case it is Scottish Gaelic.

In 2009 Scottish ministers, led by Michael Russell, won the right to speak Gaelic in the European Parliament in Brussels. This followed the EU regulation that indigenous languages should be promoted, also in political institutions. At the time Gaelic was officially recognised, the EU Parliament had acknowledged 23 languages.

Interestingly, the press reported on the fact that ‘Mr Russell is the only Scottish minister to have a smattering of Gaelic, while his colleagues, including Alex Salmond, do not speak the language at all’.

The article in The Telegraph, written by the Scottish political editor Simon Johnson, continues to explain that this move ‘follows a similar agreement that allows Welsh to be used in EU meetings, but five Welsh Assembly ministers, including Rhodri Morgan, the First Minister, are fluent’.

This fact sheds light on the UK Parliament’s response to the use of Welsh in the previous section by emphasising that when an indigenous language is to be used in political bodies, ideally there have to be speakers of this language in that political body.

A further twist in this story was provided by The Independent, which also reported on Scottish Gaelic becoming ‘an EU language’ in 2009. The article informs the reader that:

“the deal was sealed in a Memorandum of Understanding signed in Brussels yesterday by the UK's EU ambassador, Sir Kim Darroch, and by Donald Henderson, Scotland's EU director […]"

Sir Kim is quoted in the same article stating: "These arrangements will help to build a closer link between EU institutions and speakers of Scottish Gaelic by allowing them to raise their concerns and have them addressed directly in their native language. It also further promotes the long and rich cultural heritage of the Scottish people here in the EU."

But Ferguson, the author of the article in The Independent, reports that his newspaper contacted the Scottish Office, the Scottish Parliament and the Scotsman newspaper to see if these statements could be provided in Gaelic, only to be told that no one there could speak the language. (Ferguson, 2009)

As touched upon in the unit on ‘Dialect Diversity’ and underlined here, some Scots dialects are very bound up with regional identities (e.g. Doric, Shetlandic) such that speakers do not consider themselves speakers of ‘Scots’, but of the regional dialect, which is sometimes regarded as being a language in and of itself. This might have been one reason for the four MSPs from the North East taking their oaths in Doric.

In the past, some politicians have been more likely to view Scots as a disparate group of dialects, as opposed to a coherent national language. They are also often more likely to be supportive to a regional dialect - such as Doric.

At the 2015 swearing-in ceremony to the UK Parliament, three of Scottish MPs opted to repeat the oath in Scots. They were led by Dr Philippa Whitford MP (SNP) who became the first ever MP to take an oath at Westminster in Scots. She was followed by Marion Fellows MP (SNP) and Richard Arkless MP (SNP). In 2017, Dr Philippa Whitford MP (SNP) and Marion Fellows MP (SNP) again repeated their oath in Scots. Chris Law MP (SNP) and Peter Grant MP (SNP) also repeated their oath in Scots, whilst Kirsty Blackman MP (SNP) did so in Doric.

Activity 6

You will now listen to a third example of a Scottish Member of Parliament taking an oath in the Scots language:

- Listen to Dr Peter Grant MP (SNP) take his oath in Scots by selecting the period from 18:57:29 to 18:58:38.

- We have provided a transcript of Michael Russell, Peter Chapman and Peter Grant’s oaths in Scots. Read the transcriptions below and identify differences in the use of the Scots language. Do consult the DSL for this activity. Where do you see the main differences?

“…Michael William Russell swear by aal michty God that Ah will be leel an true tae Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, her airs an successors age to the law, sae help me God…”

“I Peter Chapman, depone at Ah will be leel an haad aafil allegiance tae Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, her airs an ony fa come efter her, sae help me God.”

“Ah swear bi aal michty God that Ah will aye howl a richt leel un faithfu hert tae Her Majesty Queen Elspeth an her line o airs, anent the law, micht God be ma health an state.” (Peter Grant)

5.3 Scots: A debate in parliament

An example of a motion in the Scots language put forward in the Scottish Parliament is the debate held on 25th January 2017 in the name of Emma Harper MSP (SNP) on 'Celebrating Burns and the Scots Language'. The motion is put forward and recorded first in English, followed by the Scots translation provided by the MSP.

However, in the following activity you will start the process at the other end and engage with the motion in the Scots language first of all.

Activity 7

Part 1

Analyse the motion translated by Emma Harper into Scots and recorded by Bruce Eunson.

- a.Listen to the recording and take notes on the suggested action points.

- b.In a second step listen and read the transcript below at the same time, which can support your understanding.

- c.Can you identify the six things the motion asks the Parliament to do? Highlight these in the transcript. Then compare your highlights with ours.

Part 2

Now read the motion in the English language and check your understanding of the Scots version. Did you understand all action points correctly?

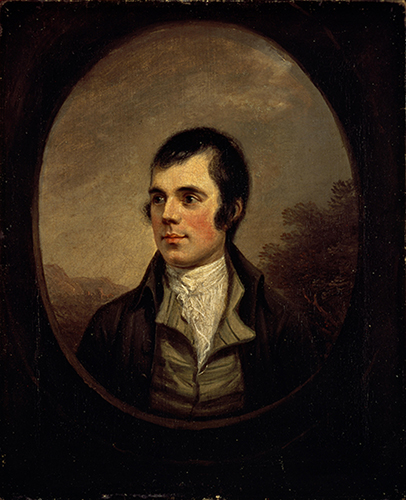

Motion S5M-03351: Emma Harper, South Scotland, Scottish National Party,

Date Lodged: 11/01/2017

Celebrating Burns and the Scots Language

That the Parliament welcomes the annual celebration of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns, which is held on 25 January each year to mark the Bard’s birthday; considers that Burns was one of the greatest poets and that his work has influenced thinkers across the world; notes that Burns' first published collection, Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, also known as the "Kilmarnock Edition", published in 1786, did much to popularise and champion the Scots language, and considers that this is one of his most important legacies; believes that the celebration of Burns Night is an opportunity to raise awareness of the cultural significance of Scots and its status as one of the indigenous languages of Scotland, and further believes in the importance of the writing down of the Scots language to ensure its continuation through written documentation, as well as oral tradition.

It is impressive to see and hear how many MSPs spoke passionately in Scots during the course of this debate. Emma Harper made a compelling plea for the Scots language when she spoke about her own life and the role Scots has played in it.

Activity 8

Read a transcription of Emma Harper’s explanation of why she put forward the motion and then summarise it in your own words.

Compare her experiences with those reported in the quote from Burns’ correspondence. What does using the Scots language mean to both?

"My mither tongue was Scots when I was a wee lassie; then, as I grew up, I lost a lot because it wasnae acceptable tae yaise the Scots words at scuil. I am rediscovering the mony words that I used as a wean that wernae yaised in scuil when I grew up on the ferm wi the other weans. We were happy tae get clarty when we louped the burns, jouked awa fae the kickin kye in the byre, managin tae hing on tae oor jammy pieces, which were clapped in oor wally naeves. I am saddened—it gars me greet—that, 40 years efter bein telt, 'Don’t speak like that—speak properly', I am now learning ma lost leid again".

Robert Burns was asked to avoid his Scots and, for the Kilmarnock edition, submit poems in English. In further correspondence to his publisher, George Thomson, when he was requested to write supplementary poems in English, Burns wrote:

- “If you are for English verses, there is, on my part an end of the matter ...

- I have not that command of the language that I have of my native tongue. In fact, I think my ideas are more barren in English than in Scottish.”

The Kilmarnock edition was printed in Scots. It did much to support, popularise and champion the Scots leid. I argue that we are richer for this decision.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

Harper and Burns had the same experience – both were told that speaking/writing in Scots was not acceptable, it was not a ‘proper’ language. Both were asked to give up on an aspect of their identity.

Burns stated to he could not express his ideas adequately in English, and Harper tells us that she feels like crying when she considers that she is now, after 40 years of avoiding using Scots, rediscovering and learning her mother tongue again.

Burns refused to write in English and Harper thinks that printing Burns’ famous poetry collection in Scots has greatly enriched Scottish culture.

For Harper and Burns using the Scottish language is an aspect of their identity and cultural belonging.

5.4 Scots: Parliamentary discussion

The parliamentary debate you studied in section 5.3 is a rare example of Scots being used in Parliament. This debate was also memorable as it was a very passionate discussion of issues regarding the use and importance of the Scots language in Scottish culture. Therefore, it is worth reading/listening to more of the Scots spoken in that particular debate. You can watch the debate or read the substantially verbatim written record of the debate in the Official Report. The closing speech delivered by The Minister for International Development and Europe, Dr Alasdair Allan (SNP), exhibits particularly rich Scots.

In general, however, with the exception of motions or questions that are consciously about Scots, it is very rare to see Scots in written form in the Scottish Parliament. Similarly, with the exception of oath-taking or debates or questions that are consciously about Scots, it is very rare to hear broad Scots being spoken in the Scottish Parliament. It is not uncommon, however, to hear the odd piece of Scots vocabulary, phraseology, or grammatical constructions within otherwise English sentences.

The Official Report of the debate you have engaged with, records, for example, usage of such words as stramash; blether; wisnae; daft-lassie question; high heid yins; and wrang - within otherwise English sentences. The reason why this is the case lies in the Scots language policy. The Official Report is the written record of the proceedings of the Scottish Parliament. The SPCB Language Policy states that: 'when Scots is used in meetings of the Parliament and committee meetings, the Official Report incorporates that language in the body of the text' (SPCB Language Policy, p. 3).

Activity 9

Part 2

Listen to the recording of this statement and then record yourself speaking these three sentences. This time, try not to read the sentences from the page but speak them from memory. This will help you improve your pronunciation and intonation and it will make your Scots sound more natural.

Transcript

Listen

Fit is so wrang wi wantin to speir as part o the census aboot foo much money we mak and fit wye we speak at hame. I cannae see oniethin wrang wi that. I havenae heard onie argument today that persuades me itherwise.

Model

Fit is so wrang wi wantin to speir as part o the census aboot foo much money we mak and fit wye we speak at hame. I cannae see oniethin wrang wi that. I havenae heard onie argument today that persuades me itherwise.

By contrast, when Gaelic is used, ‘the Official Report incorporates the Gaelic text before the report of the English interpretation’. And where a language other than English (not Scots or Gaelic) is used, the SPCB policy is ‘normally [to] publish the report of the English interpretation only, with a note to indicate that the text is not in the original language used’ (SPCB Language Policy, p. 3).

Although English is the working language of the UK Parliament, in practice, as in the Scottish Parliament, Scottish MPs will utilise Scots words, phrases and grammatical constructions within their English speech. Hansard, the House of Commons Official Report, records various instances of Scots within otherwise English sentences, such as stramash, bairn, wisnae, weel-kent and blether.

As in the Official Report of the Scottish Parliament, Scots is incorporated without translation.

Consider, for example, the comment of Charles Kennedy MP (Liberal Democrat) during a 2013 debate about the process for Scotland holding a referendum on independence, as recorded in Hansard: ‘in being entrusted with that responsibility, Holyrood must not turn a stooshie into a stramash’ (Hansard, 2013).

Activity 10

What do you think about the fact that Scots is incorporated in parliamentary business without interpretation?

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

I think it is because of the similarities Scots today has with English. It’s not the same as the need to translate Gaelic. There is probably an assumption that anyone understanding English can also understand Scots – when used in parliament – as many Scots words have been incorporated into the English language today as well.

5.5 Political recognition and protection of Scots

This section details how Scots came to have its first official government policy for Scotland, the UK and Europe.

The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML) was adopted by the Council of Europe in 1992 in order to protect and promote historical, regional, and minority languages in Europe.

In 2001, the UK Government ratified the Charter in respect of Scots and Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, Welsh in Wales, and Ulster Scots and Irish in Northern Ireland. Manx Gaelic and Cornish were subsequently added in 2003. Scottish Gaelic, Welsh and Irish were ratified under Part III of the Charter, which explicitly requires action to be taken. Scots, Ulster Scots, Manx Gaelic, and Cornish, however, were ratified only under Part II - which is predominantly a statement of objectives and principles, without explicit requirement for action.

The responsibility for the implementation of the Charter with respect to Scots and Scottish Gaelic was devolved to the Scottish Parliament. In practice, the action taken by the Scottish Executive (termed Scottish Government from 2007) has varied considerably over the years dependent on the priorities and approach to Scots of the party in government.

It would appear that the UK Government’s ratification of the Charter in respect of Scots in 2001 was not called for by the Labour Scottish Executive. The subsequent devolution of responsibility for its implementation to Holyrood was not greeted with enthusiasm. For example, this is an extract from a 2002 speech by the Labour Minister for Tourism, Culture and Sport, Mike Watson:

I dipped my toe in that water [debate as to language versus dialect status of Scots] at the Cross-Party Group last week, and my ears are still ringing, but the view had been taken, when the UK Government announced its intention of signing the Charter, that Scots will be firmly regarded as a language...

Action taken under the Labour Scottish Executive was minimal. When questioned in 2002 about what it was doing to protect and promote Scots under the European Charter, the Executive responded that it ‘[did] not consider that any action is necessary to comply with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages’, and that it had neither ‘formulated any policy on the numbers of speakers of Scots,’ nor ‘set any targets to increase the numbers of Scots speakers’ (Niven, 2002, p. 24; Bryce and Humes, 2003, p. 264).

Three years after the inclusion of Scots in the ECRML, in 2004 the Council of Europe's Committee of Experts reported as follows:

There is no official policy for Scots and the authorities whether at local or regional level (Scotland) have not taken any steps to protect the language.

The Committee of Experts has been informed of few initiatives undertaken to promote the Scots language.

The Committee of Experts has not received any information of any particular measures adopted by the Scottish Executive to facilitate and/or encourage the use of Scots.

This state of affairs did not change during the remainder of Labour’s time in power between 2004 and 2007, when the duration of the Labour Executive came to an end, and the Scottish National Party took the lead.

In 2007, the SNP formed what was now called the Scottish Government. That Government, between 2007 and the present day, has taken an active and positive approach to the Scots language. Some significant examples are outlined below:

- The establishment of a Ministerial Working Group (MWG) on the Scots language in 2009, which reported to the Government in 2010. Consisting of prominent Scots academics, writers, educators, and activists, the group members were tasked with advising the government on developing a strategy for Scots. See the full report of the Ministerial Working Group.

- The inclusion of the first ever question on the Scots language in the 2011 census. This had been opposed by the previous Labour Executive.

- The creation in 2011 of the post of Minister for Learning, Science & Scotland’s Languages. Dr Alasdair Allan, a speaker and advocate of both Scots and Gaelic, was appointed to post.

- The appointment in 2014 of four Scots Language Co-ordinators, to support and promote the teaching of Scots in Scottish schools.

- The publication in 2015 of the first ever Scots Language Policy. The policy clearly states the importance Scots as one of the three indigenous languages of Scotland and sets out the Government’s intent to expand its usage into all aspects of public life. The policy itself was produced in both Scots and English, embodying the Government’s commitment to promoting Scots as a language appropriate for all forms of communication.

Please note: The SNP had also previously supported the introduction of a Scots Language Act. The SNP’s commitment to equal legal status for the Scots language in the form of an Act was dropped in 2007. This was a time when polls suggested that the SNP may overtake Labour as the largest party in the Scottish Parliament. Perhaps the SNP took greater account of the likely political and financial pressures of running a government?

Respected author and Scots activist, James Robertson, for example, notes that, given that Scots has perhaps as many as 25 speakers for every one speaker of Gaelic, ‘one can see why the thought of spending 25 x the Gaelic budget on Scots is a scary prospect’ (Douglas, 2016, p. 36).

Activity 11

To summarise, take a note of what you consider the milestones that led to the level of official recognition the Scots languages has in Scotland today.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your milestones might be different.

- 1992 – ECRML

- 2001 – UK Government ratified the Charter in respect of Scots and Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, Welsh in Wales, and Ulster Scots and Irish in Northern Ireland

- 2007 – SNP came into power

- 2009 – MWG on the Scots language

- 2010 – MWG report to Scottish Government

- 2011 – inclusion of the first ever question on Scots in a census

- 2014 – appointment of 4 Scots language coordinators

- 2015 – Scots Language policy launched

5.6 The main political parties and Scots

In the previous section you learned about the impact of different governments on the official recognition of the Scots language in Scotland. In this section, you will look at the policy positions of three main political parties in Scotland (SNP, Labour, Conservative and Unionist) towards Scots.

Scots language and Scotland’s main political parties

While reading the three sections which illustrate vastly different standpoints, consider what factors may lie behind the party positions outlined here.

Scottish National Party

The SNP has consistently included mention of Scots within its manifesto, although it’s positioning towards the language has changed over the years. The 1999 manifesto, for the first elections to the Scottish Parliament, stated that: ‘English, Gaelic and Scots must co-exist on an equal basis in Scotland, and we will grant Scots and Gaelic “secure status” in the Parliament and national life’ (1999 Manifesto, p. 28).

The 2003 Holyrood manifesto was even more explicit, stating that ‘the SNP in government will introduce a Languages Act, giving secure status for the Gaelic and Scots languages’ (2003 Manifesto, p. 18).

By the 2007 Holyrood election, the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 had been introduced by the then-Labour Executive. The SNP manifesto in 2007, however, made no mention of equal status for Scots and Gaelic. Instead, it committed only to: ‘promot[ing] an increased awareness of Scots and its literature. This will include introducing a question on Scots in the census and ensuring that European obligations to develop the language are honoured. We will actively encourage the use of Scots in education, broadcasting and the arts’ (2007 Manifesto, p. 57).

As you read in the previous section, as the party of government, between 2007 and 2011, these commitments were broadly honoured. In its 2011 manifesto, building on the work undertaken since 2007, the SNP committed to:

‘support[ing] the introduction of a Scottish Studies element within the curriculum and see this as an important vehicle for protecting and promoting Scotland’s languages and also their literature. We will develop a national Scots language policy, with increased support for Scots in education, encouragement of a greater profile for Scots in the media, and the establishment of a network of Scots co-ordinators’.

By the next Holyrood elections in 2016, as you learned in section 4, these commitments had also broadly been honoured.

The SNP manifesto for the more recent Holyrood elections in 2016, which saw the party once more re-elected to government, contained only limited reference to Scots: stating in the final sentence of the A Creative Future section that, ‘we will also provide support for the Scots language’ (2016 Manifesto, p. 43).

Labour Party

Neither Labour’s 1999, 2003, or 2011 Holyrood manifesto made any reference to Scots.

Its 2007 Holyrood manifesto, however, included the following:

‘Given its diverse nature, we will investigate the best way to promote Scots and will work to build a consensus on the most appropriate role in our society for it. We will support the development of children’s literature in Scots.’

This specific focus on Scots in 2007 might have been the result of the strong position of the SNP in Scotland at the time, when polls suggested that the SNP may be an electoral threat to the then current Labour Executive. In contrast, Labour’s latest 2016 manifesto stated only: 'We recognise Scotland’s rich cultural heritage including Gaelic, Scots and Nordic' (The Parties and Scots, 2016).

Labour were the only party to make such a division in terms of separating languages into Gaelic, Scots and then also to Nordic.

Conservative and Unionist Party

None of the party’s Holyrood manifestos (1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2016) make any reference to Scots.

5.7 In the context of Independence

In the run-up to, and following, the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, issues relating to constitutional politics have been a focus for the political parties in Scotland. Is it possible that these issues have also informed the approach to the Scots language?

Political opponents of independence have often associated the promotion of the Scots language with the promotion of Scottish nationalism.

For example, when the Scottish Government announced in 2015 initiatives to support the Scots language, such as a Scots Language Policy and a Scots Language Ambassadors scheme, Conservative and Unionist MSP Alex Johnstone said:

"This is a predictable stunt from a Scottish Government more interested in pandering to patriots than improving education. When it could be trying to push Scotland’s schools up global league tables, or closing the attainment gap, it’s actually trying to stir up the constitution in any way it can. It’s been well proven that our school children would benefit far more from learning international languages which could open all kinds of doors for them."

In many nationalist movements, such as in Catalonia, language and culture do play central roles. In Scotland, however, the SNP promote what is called a ‘civic nationalism’, focused on political and economic issues.

For example, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon, in a defining address in 2012, said:

“I don't agree at all that feeling British – with all of the shared social, family and cultural heritage that makes up such an identity – is in any way inconsistent with a pragmatic, utilitarian support for political independence. My conviction that Scotland should be independent stems from the principles, not of identity or nationality, but of democracy and social justice.”

Activity 12

In the 2013 White Paper on independence, Scots is mentioned only briefly on page 312, noting: ‘the inspiration and significance we draw from our culture and heritage, including Gaelic and Scots’, which ‘shap[e] our communities and the places in which we live' (Scottish Government, Scotland's future, 2013 p. 312).

- You may be from Scotland, you may be from another country from anywhere in the world – to what extent do you think Scots will continue to have a place not only in Scottish cultural life – but also in Scottish politics?

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

The political party in power in Scotland today is the SNP – and has been for a number of years. As explained in this unit, the SNP are supportive of the Scots language, just as they are of Gaelic. The acceptance of the use of Scots in schools, together with evidence that it is good for the pupils, is also a signal that the politicians will continue to promote respect for Scots in many aspects of public life.

The Scots Language policy has helped develop a much wider acceptance of Scots as one of the three indigenous languages of Scotland – it has made Scots something politicians and educators cannot push to the side. The most important aspect to me yet is that the developments outlined in this unit help shape Scots speakers identity as bilingual people in a multilingual Scotland.

5.8 What I have learned

Activity 13

The final activity of this section is designed to help you review, consolidate and reflect on what you have learned in this unit. You will revisit the key learning points of the unit and the initial thoughts you noted down before commencing your study of it.

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- Different legislation for Scots and for Gaelic in Scotland

- Instances where Scots has been used in both the UK parliament and the Scottish Parliament

- The different approaches taken by the different political parties in Scotland

Further research

The Advocacy section of the Scots Language Centre.

Read this interesting BBC News article on ‘Ministers reject calls to end Westminster Welsh language ban' from 9 June 2016.

Robbie Meredith reports on BBC News Northern Ireland on the debates surrounding the status Ulster Scots in ‘Ulster-Scots 'forgotten in some ways' on 28 June 2017.

This is a written record of the debate held in the Scottish Parliament on 25th January 2017 in the name of Emma Harper MSP (SNP) on 'Celebrating Burns and the Scots Language' as published in the Official Report.

The closing speech delivered by The Minister for International Development and Europe, Dr Alasdair Allan (SNP), exhibits particularly rich Scots.

The Ministerial Working Group (MWG) on the Scots language, established in 2009, reported to the Government in 2010. Consisting of prominent Scots academics, writers, educators, and activists, the group members were tasked with advising the government on developing a strategy for Scots.

Read the full text of the Scots Language Policy from 2015.

Now go on to Unit 6: Food & Drink.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Course Image: Supplied by Bruce Eunson/Education Scotland

Activity 2 Image: Library of Congress-Artwork by Isaac Cruikshank, Published by S.W. Fores, No. 50 Piccadilly, 1799 Jan 15

Activity 3 Image: Mike Pennington / Muckle Flugga from the air. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Section 5.1 image of Scottish Parliament: Klaus with K. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Section 5.1 image of UK Parliament: Mdbeckwith. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Section 5.3 image: Robert Burns, 1759 - 1796. Poet. Photographer: Antonia Reeve. Bequeathed by Colonel William Burns 1872. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/search/artist/alexander-nasmyth

Section 5.5 image: European Parliament Buildings, Steve Cadman. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Section 5.7 image: Scottish Independence graffiti by Walter Baxter. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Text

Extract on page 9: HM Government (2017) Use of the Welsh language in the Welsh Grand Committee at Westminster: Government Response to the Committee’s Fourth Report [Online], available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmproced/1043/104302.htm Reproduced under the terms of the OGL, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence

Extracts in Activities 7 & 8: The Scottish Parliament (2017) Motion S5M-03351: Emma Harper, South Scotland, Scottish National Party, Date Lodged: 11/01/2017 Celebrating Burns and the Scots Language [Online], available at https://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/28877.aspx?SearchType=Advance&ReferenceNumbers=S5M-03351 Contains information licenced under the Scottish Parliament Copyright Licence. https://www.parliament.scot/Fol/Scottish_Parliament_Licence_2017.pdf