Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 1:14 AM

Unit 7: Arts and Crafts

Introduction

In this unit you will consider the use of Scots language in the study of the Art and Crafts of Scotland. Scottish art is generally agreed to be the body of visual art made in what is now Scotland, or about Scottish subjects, since prehistoric times. The earliest examples come from the Neolithic period, then from the Bronze Age where there are examples of carvings with the first representations of objects, cup and ring marks. Elaborately carved Pictish stones and impressive metalwork then emerged in Scotland in the early Middle Ages.

In the 18th century Scotland began producing artists who became significant internationally. The Royal Scottish Academy of Art was created in 1826, and portrait painters of this period include Andrew Geddes and David Wilkie. William Dyce emerged as one of the most significant figures in art education. The late 19th century art scene was dominated by the work of the Glasgow Boys and The Four, a group which included Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Both groups gained international reputation for the combination of Celtic revival, Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau in their work.

The Glasgow Girls is the name nowadays used for a group of female designers and artists including Margaret and Frances MacDonald, both of whom were members of The Four. Women were able to flourish in Glasgow in this “period of enlightenment” taking place between 1885 and 1920, where they were actively pursuing art careers and the Glasgow School of Art had a significant period of international visibility.

Important details to take notes on throughout this unit:

The role of Glasgow-based female Scottish artists

How Scots language can appear in formal correspondence when there is jest implied or informality sought

Craftwork and other trades in Scotland and their influence on Scottish surnames

How employment areas such as weaving or basketry carry a wealth of Scots vocabulary.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the four important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these four points, as well as any assumption or question you might

7. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: A farm-servant, a ploughman, a married skilled farm worker who occupies a cottage on the farm and is granted perquisities in addition to wages.

Example sentence: “The smell o’ neeps is i’ the wund; Hinds roond the doors are crackin’.”

English translation: “The smell of turnips is in the wind: Farm workers round the doors are cracking’.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

The smell o’ neeps is i’ the wund; Hinds roond the doors are crackin’.

Model

The smell o’ neeps is i’ the wund; Hinds roond the doors are crackin’..

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Guthrie’s painting

The picture ‘A Hind’s Daughter’ is a famous Scottish painting by Sir James Guthrie (1859 – 1930). Guthrie became one of the leading painters in the group of artists called The Glasgow Boys.This painting is one of the artist’s most distinguished and well-known works. Apart from the skill exhibited in the painting, the content of the work is notable.

Here is a girl in the middle of a cabbage or kail patch. She stares confidently out despite the fact that her standing in society will be from the poorer farm workers; a group of workers more likely not to meet the ‘camera’ eyes rather than gaze back. She grips her knife solidly and seems to have been disturbed at her job, seeming as though, after ‘we’ have looked, she’ll get back to work.

She is not posing for the artist, she stops naturally without any artifice. You may wonder: Is this painting making a statement about Scottish confidence?

“The small girl has just straightened up after cutting a cabbage and looks directly at the viewer. Girl and landscape seem inextricably merged in this essentially Scottish scene. A hind was a skilled farm labourer, and cabbage (or kail) a staple diet of Scottish hinds and their families.

Guthrie painted the picture in the Berwickshire village of Cockburnspath, where he opted to stay during the winter, unlike his Glasgow friends who returned to the city at the end of the summer. The warm earth colours and distinctive square brush strokes confirm the profound impact Bastien-Lepage's painting made on Guthrie.”

Related word:

Definition: broad, flat leaf, as the outer leaves of cabbage or lettuce, the leaves of rhubarb, tobacco, etc.

Example sentence: The bairns geed tae scuil wi only a cauld kale blade ta aet fir thir piece.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word.

Activity 3

Part 2

Now click to hear the example sentence read by a Scots speaker. You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

The bearns tae scuil wi a cauld kail blade in their pockets for a piece.

Model

The bearns tae scuil wi a cauld kail blade in their pockets for a piece.

Language links

The Scots word blade has a close connection with the German language, in which a broad leaf is a blatt. The word for leaf in old Norse was blað, old high German blada and old Dutch blad. The word evolved in the German language and in medieval times, the word for leaf was blat, yet in some areas it remained blad. In the Dutch language to this day a leaf is a blad.

7.1. Glasgow and famous female artists

Glasgow lassies

In the 1960s there began an attempt to balance the degree of plentiful discussion awarded to the group of the Glasgow Boys, whom Guthrie was a member of, by giving due attention to the work of the city’s women artists. It is thought that William Buchanan, then Head of the Scottish Arts Council, who was the first to use the name Glasgow Girls in the catalogue for the 1968 Glasgow Boys Exhibition.

The term was given further emphasis by Jude Burkhauser in 1990 when organising the major exhibition Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design 1880-1920. According to the exhibition, the group of female artists consisted of Jessie Marion King, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Frances Macdonald MacNair, Helen Paxton Brown, Bessie MacNicol, Norah Neilson Gray.

“Two of the most prominent Glasgow Girls were also members of The Glasgow Four – the sisters Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh and Frances Macdonald MacNair, who formed a coalition with their husbands Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Herbert MacNair.

Together they were instrumental in the Celtic Revival, the development of the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau’s distinctive Scottish brand, a style which is instantly recognisable today. Artists Annie French and Bessie MacNicol are also widely recognised today for their contributions to drawing, printing and painting.”

Joan Eardley

Joan Eardley was a major figure in 20th century Scottish Art. She died in 1963, aged 42, ending her artistic career tragically soon. During her time she concentrated on two major themes and her career can be divided into three distinct phases. The first phase began when she enrolled at Glasgow School of Art in 1940 through to 1949 when she successfully exhibited paintings created when travelling across Italy.

Then from 1950 to 1957 she painted the city of Glasgow, in particular the children of Townhead which was a distressingly deprived area. These scenes and portraits of urban poverty are then contrasted sharply in her third phase in Eardley’s depiction of Catterline, a fishing village south of Aberdeen where she moved permanently in 1961.

From then until the end of her life the rural landscapes and seascapes she saw around her, and which ‘Boats on the shore’ is an example, dominated her output.

A major exhibition of her work took place in 2017 in Edinburgh’s Scottish National Gallery. Entitled A Sense of Place, it included the two themes of her work with many previously unseen drawings and sketches. Often painting out of doors, her depictions of the wild seas and overcast skies in the north east of Scotland contrasted sharply with her tenement scenes with Glasgow weans.

These central objects of Eardley’s paintings also feature in a review of the ‘A Sense of Place’ exhibition in the Scottish National Gallery in the Financial Times.

Activity 4

Part 2

In this part of the activity you will work with one of Eardley’s most famous Glasgow paintings, ‘Two Glasgow Lassies‘ (1962–63).

Before actually looking at the painting, listen to a description of this painting in Scots. While listening, you might want to have a go at sketching this painting according to the description. Then look at the painting which is featured in the Wullschlager article.

Part 3

Again, here is an opportunity to practise your spoken Scots by reading out the description of Eardley’s painting. As always in this type of activity, compare your recording with our model and repeat the process until you are happy with your own Scots pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

This picter shaws twa wee lassies sittin thegither lookin oot at the painter. Wan has her aims foldit an the ither has her hauns oan her frock. The wan wi black herr an a reid kinna bunnet roon her heid, disna look ower happy. The wan wi broon herr looks in a kina dwam as she stares oot.

Model

This picter shaws twa wee lassies sittin thegither lookin oot at the painter. Wan has her aims foldit an the ither has her hauns oan her frock. The wan wi black herr an a reid kinna bunnet roon her heid, disna look ower happy. The wan wi broon herr looks in a kina dwam as she stares oot.

And if you have not understood all words in the description, here is our translation of the short text into English.

Answer

This picture shows two girls sitting together and looking out at the painter. One has her arms folded, the other has her hands on her dress. The one with black hair and a red type of scarf around her head does not look very happy. The one with brown hair looks as if she is in a day-dream as she gazes fixedly out (at the observer).

7.2 The Monarch of the Glen

Completed in 1851 by the English painter Sir Edwin Landseer, The Monarch of the Glen is an oil-on-canvas painting of a red deer stag. It had been commissioned as part of a series of three panels to hang in the Palace of Westminster in London. The image became one of the most popular paintings throughout the 19th century. Reproductions in steel engraving sold very widely and the painting itself was then bought by companies to use in advertising.

By the mid-20th century the painting had become quite the cliché, described by the Sunday Herald as “…the ultimate biscuit tin image of Scotland: a bulky stag set against the violet hills and watery skies of an isolated wilderness.” (Jeffrey, 2005)

Language Links

The stag in the painting has twelve points on his antlers, which in deer terminology makes him a "royal stag" but not a "monarch stag", for which sixteen points are needed. The DSL definition of glen is a valley between hills or mountains. Early examples in place-names are Rutherglen (c 1160) or le Glen (1292).

Often, Scots, being a Germanic language, has close links to Scandinavian and European languages. In this case, the word glen has its roots in a Celtic language - Gaelic. It comes from the Scottish Gaelic and Irish gleann (earlier glenn).

In 2017 the National Gallery of Scotland launched a successful campaign to buy the painting, finally achieving the acquisition for £4 million. The painting is now part of the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh, on display in Room 12.

With that £4m in mind, now read the lovely tale of Orla Macdonald and The Monarch of the Glen, ‘A Painted Stag and Skooshy Cream: A Tale of Tough Negotiation Unfolds...’ as published on the website of the Scottish National Gallery. The 13 year old Orla painted her own version of this painting and her father, Gary, wrote to the National Gallery – as a reaction to the difficult negotiations around the acquisition of the original by the Edinburgh gallery - offering it for sale to them for just £2 million.

Activity 5

In this activity you will take a closer look at the communication between Orla’s father, Gary, and the Director-General of the National Galleries of Scotland.

Part 1

Read the letters by Gary Macdonald and Sir John Leighton.

- While reading, highlight the examples of Scots language used in the letters by Gary Macdonald.

- Translate into English the Scots words you identified.

Answer

b. These are the translations of the Scots words used by Orla’s father.

- folk (people)

- wee (little)

- gon yerself (go on yourself)

- awfy (awfully)

- skooshy (squirty)

Part 2

Why do you think Gary Macdonald uses a smattering of Scots in his letters to the National Galleries?

What effect does his use of Scots have on you as a reader?

Answer

This is a model answer. Your thoughts might be different.

I think that by using Scots, Gary makes the letter sound less formal and underlines that Orla’s proposition to the National Galleries should not be taken too seriously. His use of Scots in otherwise English language contexts underlines what was mentioned in other units of this course, that Scots is often called upon to contribute an element of humour to communication.

7.3 Scottish Crafts

Scottish indigenous crafts are crafts that have their origins in the cultures of Scotland. Other terms often used to describe them include heritage, traditional and folk art. The Scottish Indigenous Crafts website, run by the Really Interesting Objects initiative, offers useful definitions of these terms, which are added to by Scottish Indigenous Craft practitioners or initiative members themselves.

“What are Scottish Indigenous Crafts?

Scottish indigenous crafts are those which represent skills and trades originally acquired and practiced out of necessity. They are a product of functional life with an identifiable style specific to Scotland. Historically they reflect locally available materials and resources and are part of Scottish regional and national cultural identity. They can be expressive and innovative. They are sometimes described as folk art, rural craft, traditional craft and heritage craft.”

Activity 6

Part 2

Taking a closer look at the items in the list from Part 1 of this activity, which do you think are Scots words? Highlight these now.

Discussion

Please note: The term taatit is not listed in the DSL, although it is a Scots term. It is a specific term used in Shetland in connection with ‘rug’. Taatit rugs are the pile bedcovers traditionally used in Shetland. The Shetland heritage website provides information on a taatit rug exhibition in 2015.

Part 3

Now use the DSL to look up the words you highlighted in Part 2 and add these to your own glossary of Scots vocabulary and phrases.

Clearly craft industries of Scotland cover an impressive range of products and areas, and they make up an important component of the Scottish economy and contribute in a major way to the development of the Scottish tourist industry. A survey carried out on behalf of Craft Scotland and other craft agencies in the UK revealed that Scottish craft contributes over £70 million to the economy, from an estimated 3,350 Scottish craft makers. The summary of the survey provides an interesting insight into who the people are that consider themselves crafts people of Scotland today:

- Craft careerists: who committed to the idea of craft as a career and started their businesses shortly after finishing their first (or second) degrees in a craft-related subject. (38.8%)

- Artisans: who do not have academic degrees in the subject but nevertheless have made craft their first career. (12.2%)

- Career changers: who began their working lives in other careers before taking up craft as a profession, often in mid-life. (31.6%)

Returners: who trained in art, craft or design, but followed another career path before ‘returning’ to craft later on. (17.5%)

(Craft in an Age of Change: Summary Report, 2012, p. 24.)

![]()

When it comes to the materials used in Scottish crafts, it is interesting to compare the findings of the Creative Scotland study as opposed to the list of Scottish crafts posted on the Scottish Indigenous Crafts website from Activity 6.

Below is the ranking of the most commonly used materials cited in the Crafts in an age of change: Summary report:

The five most commonly used materials in current Scottish crafts

- Metal and mixed materials in Jewellery – 23.0%

- Textiles (exc. weaving) – 21.1%

- Ceramics – 18.3%

- Wood (exc. furniture) – 12.2%

Glass 11.1%

(2012, p. 24.)

You see that there are some materials that are not mentioned at all in the Scottish Indigenous Crafts website list, such as ceramics and glass. On the other hand, the range of materials in the Scottish Indigenous Crafts website list is much wider and includes more unusual materials such as horn or ropes which are made from hemp.

Why do you think there might be such a difference?

Might this be an issue of perceptions?

Can this have something to do with what some might consider ‘real crafts’ versus more creative or ‘arty’ crafts?

Do you think the items listed as indigenous crafts might be considered ‘every day/traditional goods’ as opposed to more innovative and in some cases ‘luxury’ products mentioned by the makers in the Creative Scotland study?

Could there be other reasons, i.e. the contributors to the Scottish Indigenous Crafts website list do not engage with crafts as a career?

If you want to find out more about makers, materials, crafts and interesting items, do explore the Craft Directory on the Craft Scotland website, which makes for a compelling read.

7.4 Scottish surnames and crafts

In addition to the impact crafts have today, the historical importance of craft and trades is even reflected in the very names of Scotland’s people, although they may individually no longer be involved in the activities their surnames attest. Permanent surnames began to be used in Scotland around the 12th century, but were initially mainly the preserve of the upper echelons of Scottish society.

However, it gradually became necessary to distinguish ordinary people from one another by more than just the given name and the use of Scottish surnames spread. In some Highland areas, though, fixed surnames did not become the norm until the 18th century and in parts of the Northern Isles until the 19th century.

The influences on the development of Scottish surnames are many and varied and often more than one has resulted in the surname that we know today. Surnames today are used to indicate family relationships; however this has not always been the case. Surnames in the past have been based on many factors such as occupation, location, the patronymic (the adding of 'son' or 'Mac' to the father's first name), physical characteristics, localised spelling conventions and employer's names.

In many cases, similar, or in some cases identical, surnames have been derived from entirely different sources and different areas of Scotland. Thus the modern 'consistency' in naming conventions has been based on a possibly 'inconsistent' starting point.

It was only in 1855 that the compulsory registration of births, deaths and marriages started in Scotland and registrars started to insist that individuals should use the same surname as their father. The first surname survey, covering registrations during the years 1855, 1856 and 1858, was published by the Registrar General in 1860. Some common Scottish last names come from the occupational bynames based on the occupation, or job, of their owner. Such as: Webster (a weaver).

A well-known literary example that features a Wabster is Burns’ humorous song, ‘Sic a wife as Willie had’ of 1792.

“It is comic song telling the tale of a weaver and his 'not so comely' wife. According to tradition, Linkumdoddie was the name of a small cottage situated at the point where the River Tweed and Logan Water converge. During the latter days of the eighteenth century, it is known to have been inhabited by a weaver and his wife.

It is said that whilst travelling between Edinburgh and Dumfries, Burns stayed near Linkumdoddie on a number of occasions. Perhaps he sought inspiration for this song from the weaver and his wife!”

Activity 7

In this activity you will focus on the surname Webster and its various forms that were in common use in Scots: Wabster or the variants Wobster, Webster, etc.

Here is a sample sentence from the Dictionary of the Scots Language which is a quote from a publication from 1721.

Sc. 1721 Ramsay Poems (S.T.S.) I. 189:

- Scots Language : He catch'd a crishy Webster Loun At runkling o' his Deary's Gown.

- English translation: He caught a greasy weaver boy ruffling his sweetheart’s dress.

Part 1

Practise speaking this sentence, try not to read if of the page but speak it from memory as this will improve your pronunciation and intonation.

Transcript

Listen

He catch'd a crishy Webster Loun At runkling o' his Deary's Gown.

Model

He catch'd a crishy Webster Loun At runkling o' his Deary's Gown.

Part 3

And finally, practise your spoken Scots again by reading out loud the first verse of Burns’ song.

Transcript

Listen

Willie Wastle lived on the banks of the Tweed, At the spot they called Linkumdoddie; Willie was a good weaver, He could have packed a ball of thread with anyone: He had a wife who was sullen and had a dull complexion, Tinkler (Gypsy) Maidgie was her mother; Such a wife did Willie have, I would not give a button for her!

Model

Willie Wastle lived on the banks of the Tweed, At the spot they called Linkumdoddie; Willie was a good weaver, He could have packed a ball of thread with anyone: He had a wife who was sullen and had a dull complexion, Tinkler (Gypsy) Maidgie was her mother; Such a wife did Willie have, I would not give a button for her!

7.5 Weavers

In this section you will take a closer look at weaving and the weaving industry in Scotland.

Activity 8

To start with, you will learn some Scots words which are specific to the weaving industry. When you look up these words in the DSL, you will not always find them or a direct translation. In some cases you would need to work with the example sentences to understand how they are used in the weaving context.

Use the DSL, or the example sentence from the DSL, to derive a translation into English of these weaving terms.

a.Shifter

Per. 2000 Betty Stewart in Ian Macdougall's Voices from Work and Home 388:

When ah began in the mill ah wis a shifter, and that wis takin’ the bobbins off the machines before they were automatic.

- b.Bobbin

- c.Pass

- d.Spinnin

- e.Warp

- f.Weft

Answer

- a.Shifter - a person who takes the full spools of thread off the spinning frames and replaces them with empty ones

- b.Bobbin – A spool (of or for thread)

- c.Pass – a passage between looms in a weaving shop

- d.Spinnin – spinning / to do with spinning thread

- e.Warp – to move to and fro, to zig-zag, to flurry or whirl about

- f.Weft – the woof or cross-threads of a web of cloth, to make a web

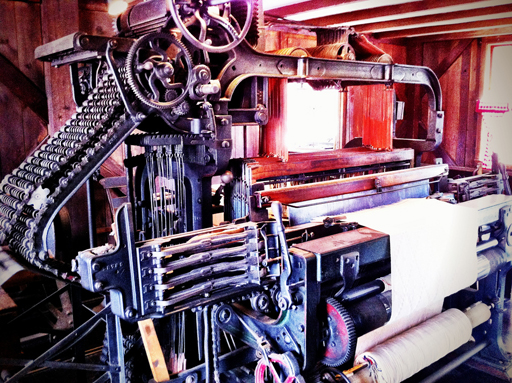

Weavers used the threads created by spinners to make a variety of fabrics and materials. Originally weavers worked from home - women and children worked in their own cottages - until the Industrial Revolution when big weaving sheds were set up with power looms. Weavers in Scotland produced: quality tweeds in the Borders, cottons in the west, damask in Dunfermline, patterned shawls in Paisley and jute in Dundee.

After a famous visit of George IV to Edinburgh in 1822, tartan was produced commercially as it enjoyed a big jump in demand. Spinners and weavers often fell out, as weavers thought they were superior. The Weaving Industry was one where workers recited many songs, including many which feature an abundance of Scots language.

The songs of the millworkers of Scotland are perhaps best embodied by Dundonian Mary Brooksbank's song, Oh Dear Me, also known as The Jute Mill Song.

“Of all the poems and songs that are associated with Mary Brooksbank, the ‘Jute Mill Song’ or ‘Oh Dear Me’ is probably the best known. Based on a single traditional verse which she adapted as the chorus, she managed to capture a lot more about life than just the hardships of the jute mill lassies. […] Mary Brooksbank worked all her working life in the jute mills of Dundee and the song tells of the hard life. Mary was a member of the communist party and a social activist. She self-published a book of her poems and an autobiography.

Shiftins, piecing and spinning were three of the jobs on the 'flett' (i.e. flat - the floor on which the spinning machinery stood). […] Ten and nine was the weekly wage of the mill lassies at the turn of the century - ten shillings (paid as a gold half sovereign) and nine pence.”

Activity 9

Part 1

In order to develop a more accurate impression of life in Dundee and working in the mills at the time when Mary Brooksbank was composing her song, watch this video Jute Mill Chanters & Shifters.

Part 2

Now read the three verses of the Jute Mill song and try to understand the lyrics. As you have looked up the key words to do with weaving in the previous activity, you might even be able to understand the song without looking up words in the DSL.

Please note: piecing in this context means tying together threads on the machines.

Oh dear me, the mill’s gaen fast,

The puir wee shifters canna get their rest,

Shiftin bobbins, coorse and fine,

They fairly mak ye work for your ten and nine.

Oh dear me, I wish the day was done,

Rinnin up and doon the pass is nae fun.

Shiftin, piecin, spinnin, warp, weft and twine,

Tae feed and cleed my bairnies affen ten and nine.

Oh dear me, the world’s ill-divided

Them that work the hardest are the least provided,

But I maun bide contented, dark days or fine.

There’s no much pleasure living affen ten and nine.

Part 3

And finally, listen to Mary Brooksbank herself sing and describe how she composed the song in a recording provided on the website of the Kist o Riches project.

7.6 Basketry or Basket Weaving

In this section you will learn more about one of the oldest traditional crafts in Scotland: Basketry, also known as basket weaving, is one of the oldest traditional crafts in Scotland. As you have seen with other crafts, there are many words in the Scots language that derive from these activities.

Activity 10

Part 2

Read this brief historical account of basketry in Scotland and highlight at least 5 facts you want to remember from this history. Then compare your highlights with our model answer.

7.7 Basketry and Scots language

Largely because of its long history and its geographical universality, basket weaving has a hugely rich and diverse association with Scots language. The aforementioned website Woven Communities gives a tremendous insight through its glossary of the importance and complexity of basketry throughout Scotland.

The site details the change in language used as basketry travels across Scotland, particularly up to the Northern Isles where a basket called a kishie in Shetland, or caisie in Orkney, “is used in a similar way that the back creel is used by crofters in the Highlands and Islands off the west coast of Scotland.” (Dawn, 2013).

Woven Communities also has a detailed step-by-step set of instructions by Ewan Balfour, a Shetlander, whose skill in making a kishie features numerous words such as dockans, simmens, hjogs and gloy.

Activity 11

Part 1

In this penultimate activity you will work some more with the Scots vocabulary linked to basketry using the knowledge you have gained studying this section.

Match the words below to the correct definitions.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

dockan

hjog

simmens

gloy

kishie

cassie/caissie

creel

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.A deep wicker basket carried on the back by means of a strap passing round the breast or (more rarely) the forehead, used for carrying fish, peats, potatoes

b.A basket made of straw, or of woven heather, coarse grass, reeds, “or dried dockstalks”

c.A straw basket

d.A coarse weed of temperate regions, with inconspicuous greenish or reddish flowers. The leaves are used to relieve nettle stings

e.Straw; cleaned, unbroken carefully selected and “bound up in little sheaves four or five inches in diameter”, used for making baskets, straw-ropes, bee-hives, thatching, etc.

f.A rope made of heather, grass, rushes, or esp. straw

g.The loops of straw of which a basket is made

- 1 = d,

- 2 = g,

- 3 = f,

- 4 = e,

- 5 = c,

- 6 = b,

- 7 = a

Part 2

You can explore the impressive variety of baskets produced in Scotland on the Woven Communities website, which features information about basketmaking communities in Scotland. When exploring the Basket types section, pay attention to the names of baskets, which often are Scots words, such as creel or cassie.

7.8 What I have learned

The final activity of this section is designed to help you review, consolidate and reflect on what you have learned in this unit. You will revisit the key learning points of the unit and the initial thoughts you noted down before commencing your study of it.

Activity 12

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- The role of Glasgow-based female Scottish artists

- How Scots language can appear in formal correspondence when there is jest implied or informality sought

- Craftwork and other trades in Scotland and their influence on Scottish surnames

- How employment areas such as weaving or basketry carry a wealth of Scots vocabulary

Further research

Find out more about crafts and Scottish surnames in the ‘Guide to Scottish Surnames, https://www.scottish-at-heart.com/ scottish-surnames.html

There has been an upsurge of interest in learning basketry skills in recent years and there are courses held across Scotland.

Find out more about basketry:

- The Scottish Basketmakers’ Circle is a membership organisation that promotes Scottish basket making and allied crafts through exhibitions, courses, demonstrations and lectures. Their Facebook page has lots of photographs of traditional and modern baskets in a variety of materials.

- They have also developed a sister site www.wovencommunities.org which traces Scottish vernacular basketry from the perspective of the communities who made and used them as well as the different basket types.

- The Scottish Fishing Museum in Fife has a number of original and replica baskets used in the fishing industry.

- The Am Baile website gives more information on highland history and culture. You can also watch a basketry workshop on these videos which are split into part one, part two, and part three. You need Adobe Flash Player installed on your device to watch these videos.

Basketry as an art form

- Find out about the Scottish basketmaker Lizzie Farey, who is based in Galloway and has been exhibiting her art based on traditional basket weaving techniques all over the world.

- You can also watch Lizzie weaving in her studio.

Now go on to Unit 8: Sport.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Course Image: Supplied by Bruce Eunson / Education Scotland

Activity 2 image: Sir James Guthrie (1859-1930), Oil on canvas owned by National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK

Image on page 7: Sandihal. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution -NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

Image on page 10: Glasgow School of Art by Wojtek Gurak. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

image on page 13: Monarch of the Glen goes on tour across Scotland by Scottish Government. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

Image on page 20: Jordan Rusev/123RF

Image on page 23: criggle1. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution -NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/

Image on page 24: Eagle Mills, Victoria Street, Dundee by Robert Cutts. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Image on page 27: susanvg. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution -NonCommercial-Share Alike 2.0 Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

Text

Extract on page 6: National Galleries of Scotland

Extract on page 17: https://www.scottishindigenouscraft.org/scottish-indigenous-crafts

Extract on page 19: Used by permission of the National Library of Scotland

Extract on page :24: Taken from https://www.springthyme.co.uk/1030/cd30_13.htm

Extract on page 25: The estate of Mary Brooksbank