Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 19 February 2026, 5:42 PM

Unit 3: The challenge of transfer

Unit 3: The challenge of transfer

Welcome to unit 3. Watch this video where James Lang explains the challenge of transfer.

Transcript

Transfer of knowledge

An important goal of all education is transfer of knowledge: the ability of the learners to take what they have learned in one context and apply it to a new context. In the area of anti-corruption, integrity and ethics, you want your students to take what they have learned in the Modules and apply it to ethical situations they encounter outside of the classroom: on campus, at home, in their careers, in their communities, and beyond.

When teaching a class based on E4J Ethics Module 4 (Ethical Leadership), for example, one might expect that students will take what has been learned in that lesson and use them when they find themselves in leadership positions - but they might be months or years away from assuming leadership roles in a professional environment or in their communities.

Connecting knowledge to different contexts

Research on learning shows that transfer is very difficult to achieve. People tend to learn new skills and ideas within specific contexts and then associate those skills and ideas with the context in which they learned them. The best way of helping students transfer knowledge outside of the classroom contexts in which they first encounter it is to help connect that knowledge to contexts that students encounter in their everyday lives (Ambrose, 2010).

As much as possible, you should always work to provide real-world examples of the ideas and principles that you are teaching, and - even better - invite students to identify and explain their own examples of those ideas and principles.

3.1 Hypothetical scenarios

Good teachers usually do this during their lectures or discussions. When they introduce a new idea, they provide examples of how it has appeared in the world, or they offer hypothetical scenarios in which it could appear in the world. You should make sure that at least some of your examples connect to the contexts in which students live: the histories of their own countries, the people with whom they are familiar, or the everyday contexts in which they live.

Of course, part of educating students means opening their eyes to historically and geographically distant countries and histories and people, but if you never help them see the connection between the content and their own lives, students are unlikely to transfer the course content to their lives. You will consider ways in which you could support your students in making these connections in the next activity.

Activity 3.1 Encouraging connections

Bringing to mind your own teaching experience, what techniques have you used to encourage your students to make connections between their own experience and the concepts being taught? Note down at least one technique in the box below.

Answer

Fortunately, you do not have to do all the work of making these connections yourself. If students gain a thorough understanding of the content, they should be able to identify their own examples of how the taught principles could apply in their own lives. The E4J Modules are designed to encourage lecturers and students to make these connections. A good example is this teaching is an activity from Exercise 1 of E4J Ethics Module 3 (Ethics and Society):

Students are encouraged to bring a daily newspaper to class or to access any news-related website. They are given five minutes for individual preparation – the task is to explore the front page or headlines and to identify three to five stories with a clear ethical component. After five minutes, small groups are formed to discuss and share examples. Each group is required to select one example to present to the class.

Inviting the students to comb through news reports, especially if those news reports are local, helps the students get into the habit of viewing the news through the lens of the principles you are helping them to master - and that, in turn, gets them into the habit of transferring the principles into other contexts outside of the classroom.

So, all the E4J Modules seek to invite students to engage in activities or tackle real-world scenarios in which the course content would apply. They also encourage you to discuss how the content applies to the students’ lives outside of the course. However, you should search consistently, whilst planning a course and engaged in teaching, for opportunities to facilitate transfer by inviting students to make connections between the content and their own lives.

In the remainder of unit 3 you will be introduced to three activities which illustrate how the E4J Modules seek to encourage learners to make connections between concepts of anti-corruption, integrity and ethics and their own lives. The activities illustrated below are used in E4J Ethics Module 1 to engage students with two different ethical theories: Utilitarianism and Deontology and in E4J Anti-Corruption Module 6 to explore recent research on the detection of corruption. These themes are explained in detail in the aforementioned Modules, but for clarity, a brief explanation of each will be offered to provide some context for the activities.

3.2 Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism states that the best action in a particular situation is the one that brings most advantages to the most people.

Follow the numbers on the interactive below to get a full definition.

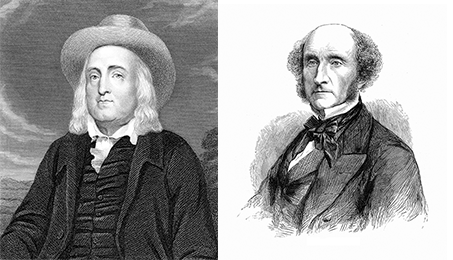

Figure 10 A definition of Utilitarianism

Two of the most important philosophers in the tradition of Utilitarianism are Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.

The following activity illustrates how the E4J materials seek to support students in transferring their knowledge of ethical principles to different contexts.

Activity 3.2 Case Study - Shipwreck

This activity is included in E4J Ethics Module 1 on concepts of ethics.

You ask the students to imagine that their ship has started to sink in the middle of the ocean. Eleven people have jumped into a life-boat that only fits ten people, and the life-boat is also starting to sink.

What should the passengers do? Throw one person overboard and save ten lives? Or stick to the principle of “do not kill”, which means that everybody will drown?

You can invite contributions from the class and even take a vote, and then ask students to reflect how different theoretical approaches (e.g. utilitarianism and deontology) will lead to different solutions that are both valid in terms of the particular approach.

What should the passengers do? According to the utilitarian approach, the answer is easy: ten lives saved will produce the most social utility, and therefore – according to utilitarianism – killing one person is the ethical thing to do.

If you would like to read more about the subject, open this article on Utilitarianism by philosopher Charles Freeland.

3.3 Deontology

The basic premise of deontology, in contrast to consequentialist theories like utilitarianism, is that an action is moral if it conforms to certain principles or duties (irrespective of the consequences).

Deontology is derived from the Greek word deon, which means duty. The one name that stands out from all others in terms of this approach is that of Immanuel Kant.

The following extract from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provides a good summary of Kant's position:

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) argued that the supreme principle of morality is a standard of rationality that he dubbed the "Categorical Imperative" (CI). Kant characterized the CI as an objective, rationally necessary and unconditional principle that we must always follow despite any natural desires or inclinations we may have to the contrary.

All specific moral requirements, according to Kant, are justified by this principle, which means that all immoral actions are irrational because they violate the CI. (Johnson and Cureton, 2018)

In layperson's terms, the Categorical Imperative can be compared and contrasted with what is often described as the Golden Rule, one that can be found in many different cultural and religious traditions: do unto others as you would want them do unto you.

It is immediately evident that this type of argument will provide solutions to ethical problems that are different from a utilitarian approach. In the shipwreck example we saw in Activity X it is no longer possible to justify killing someone, because the rule that can be deduced as universal is: do not kill.

Therefore, no matter what the consequences are, the morally correct answer would be not to kill anybody on the life-boat.

Activity 3.3 Turning knowledge to practice

This activity is included in E4J Ethics Module 4 (Ethical leadership)

The idea behind this exercise is transfer knowledge about ethical leadership into practical guidelines. In Module 4, students are encouraged to examine ten activities which Daft (2011) associates with moral leadership and then to review the five principles of ethical leadership suggested by Northouse (2010).

After carefully considering the approaches of Northouse and Daft, students are encouraged to critically evaluate these approaches, and come up with their own set of practical guidelines for ethical leadership.

If you would like to read more about the subject, open this article on Deontology by philosopher Charles Freeland.

3.4 Detection of corruption

In this final section of Unit 3, a summary of the discussion given on detecting corruption provided in E4J Anti-Corruption Module 6 will be given to illustrate how students can be encouraged to connect their understanding of ethical theories to anti-corruption practices.

Corruption can be detected through a variety of methods, some of the most common of which are reports (by citizens, journalists, whistle-blowers and self-reporting).

Self-reporting

Some States have laws and incentives that encourage individuals to report on corruption in which they played a role. This process, known as self-reporting, is often associated with private sector entities, but is applicable to corruption in any organization. Punishment for corruption can be severe, and therefore penalty mitigation is a common incentive to encourage self-reporting.

One of the challenges of addressing corruption through self-reporting is finding the balance between the investigative benefits that arise from cooperation and the prosecution of persons committing corrupt acts. While there is no general legal duty to disclose corrupt activities in many countries, specific legislation in areas such as securities and corporate law may require self-reporting. The United States Foreign Corrupt Practice (FCPA) Act, penalizing companies, registered in the US, for their activities abroad, creates a violation for failure to self-report corrupt acts involving financial books and records. In fact, many countries have provisions for penalty mitigation as an incentive to self-report. n China, there is an express provision "for reduction or exemption of the applicable sanction in the event that a person voluntarily discloses conduct that may constitute bribery" of a foreign public official, and more generally with domestic bribery (Turnill and others, 2012).

Citizen reporting

Members of the public are often the first ones to witness or experience corruption, particularly in the area of public services. To help expose corruption, members of the public can be instrumental in reporting on corruption through standard crime-reporting channels at the national or municipal level, such as the police. To encourage citizen reports on corruption, many governments have developed more direct ways for the public to report corruption. For example, specialized anti-corruption bodies can establish dedicated reporting channels for corruption offences.

In addition to specialized anti-corruption bodies, new technologies are increasingly playing an instrumental role in facilitating citizen reporting. For example, in many countries, websites and smartphone applications enable citizens to report incidents of corruption easily. Perhaps the most popular example is I Paid A Bribe in India, which has registered more than 187,000 single reports by citizens and over 15 million visitors as of August 2019. Its interactive map allows the website's visitors to monitor in which cities and sectors in India corruption occur the most as well as the amounts of bribes paid. A similar mobile phone scorecard programme was developed in the Quang Tri province in Vietnam. This allows citizens to score the performance of the administration of public services and to report on whether they had been asked to pay a bribe.

Journalism and media reporting

Journalism and the media play a key role in reporting, exposing and curbing corruption. Reporting on corruption is "making a valuable contribution to the betterment of society" and investigative journalism in particular "holds the potential to function as the eyes and ears of citizens" (UNODC, 2014, pp. 2, 6). Media reporting can be a means of corruption detection that prompts organizations and law enforcement agencies to conduct investigations (or further investigations) into allegations of corruption. Reports of corruption in the media can also be used to gather more information about and evaluate instances where corruption has been detected and requires further investigation. One highly publicised example is the Mossack Fonseca Papers case, which is commonly referred to as the Panama Papers (this case is further discussed in Module 10 of the E4J University Module Series on Anti-Corruption).

Whistle-blowing

Given that corruption can benefit the individuals directly involved, and there is a variety of means to cover up corruption within organizations, some corruption cases can only be detected if someone on the inside reports it. This kind of reporting activity is frequently called "whistle-blowing", because the reporting person sends out an alert about the activity, in the hope that it will be halted by the authorities. Usually, the whistle-blower reports the act to an appropriate internal manager, executive or board member. Some entities have established protocols for reporting. If that proves unsuccessful, whistle-blowers might raise the issue with external regulatory or law enforcement agencies or may choose to expose the matter publicly by contacting the media.

To date, the most commonly used academic definition for whistle-blowing is from Near and Miceli (1985) who define whistle-blowing as the "disclosure by organisation members (former or current) of illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers to persons or organisations who may effect action".

Activity 3.4 How to report corruption

This activity is taken from E4J Anti-Corruption Module 6.

Start of Question Identify one or more instances of local corruption, and have students debate which mechanism, e.g. whistle-blower, media, internal audit, external oversight or police investigation, is possible or effective in their community for reporting corruption in those instances.

Have students engage in open discussion of methods of reporting corruption. Lecturers can support student discussions by noting a possible drawback, concern or complexity regarding a reporting method that students did not think of. The lecturer should encourage students to think about what challenges there might be to reporting, and how they might be overcome by systemic change. Use each example to promote further student thinking and insight by having students weigh each method's effectiveness and risk.

3.5 Conclusion

This unit has explored how you can assist your students in meeting the challenge of transferring the knowledge and skills they are developing to different contexts. You have explored the idea that the best way of helping students transfer knowledge outside of the classroom contexts is to help connect that knowledge to contexts that your students encounter in their everyday lives (Ambrose, 2010).

You will find that throughout the E4J Modules there are ideas for lesson activities that invite your students to apply the ethical concepts taught to real world scenarios. You were invited to explore two examples of how this approach could be used when teaching utilitarian and deontological approaches to ethics and mechanisms for the detection of corruption.

In the next Unit you will explore the social nature of learning in more detail.

Go to Unit 4: The social nature of learning now.