Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 19 February 2026, 7:24 PM

Unit 4: The social nature of learning

Unit 4: The social nature of learning

Although we often think about learning as a solitary affair, the construction of new ideas and knowledge operates most effectively when learners combine solitary study with opportunities for discussion and collaboration with one another.

Every Module contains recommended teaching activities in which students are collaborating with one another in discussions or other group activities. Whether you pursue these recommended activities or create activities of your own, the students benefit when they can share ideas, learn from one another, and even argue and debate.

Watch this video of James Lang discussing the social nature of learning.

Transcript

4.1 Expert ‘blind spots’

Two related theories help support the proposition that students benefit from opportunities for collaboration with one another.

First, as an expert learner in a specific field, a lecturer might have developed what researchers call “expert blind spots”: in other words, they are no longer able to see the material as a new learner sees it. You might have found this in your experience thus far as a teacher: you explain something to a student that seems quite clear to you, but the student seems baffled.

Researchers who study this problem have pointed out that experts, when they are explaining their subject matter to a new learner, often skip over steps or concepts that have become so automatic to them that they are no longer consciously aware of them.

For example, if an expert swimmer were to teach someone to swim, the expert might focus on helping someone to develop perfect form in the motion of the arms and legs. In the meantime, the student might be gasping for air, as the teacher failed to instruct them in how to breathe properly throughout the strokes—something that the teacher does automatically and took for granted the learner would know.

4.2 Zone of proximal development

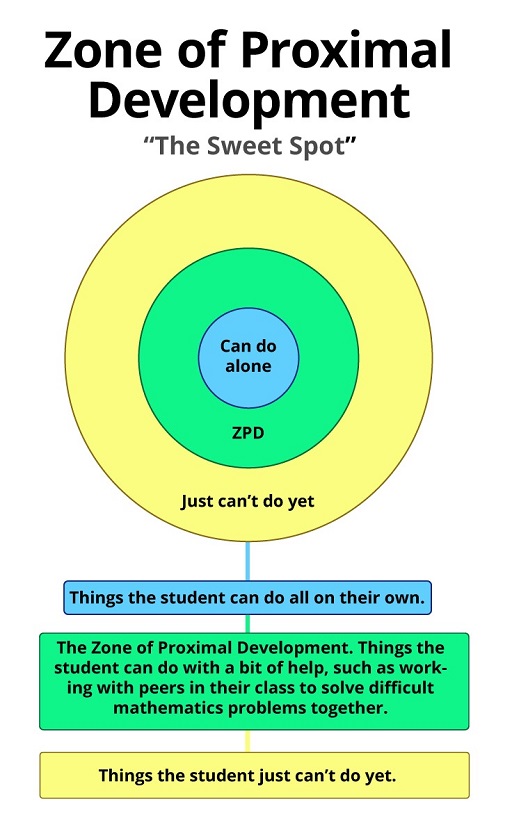

Students who are struggling together to learn something have no expert blind spots. They can thus often be more helpful to one another than the teacher can. A second theory about learning, one developed a century ago by Russian educational thinker L.S. Vygotsky, helps explain why this is so.

Vygotsky argued that we should identify two levels of ability in learners: their current state of ability, and the abilities that they might achieve with the help of experienced peers or guides. In other words, imagine ten mathematics problems of increasing difficulty. Working on his or her own, a student might be able to solve all the way through problem six. However, if that student were to join together with two peers, the three of them might be able to help each other get through problem eight.

The difference between these two levels of achievement - what the student could accomplish on his or her own and what he or she could accomplish with the help of peers - was described by Vygotsky as that student’s zone of proximal development. In other words, that zone represents the next stage of learning that the student can achieve when he or she works collaboratively with others (Vygotsky, 1978).

The following activity illustrates how the E4J Modules utilise social learning methods to support students’ engagement with ethical concepts.

Activity 4.2 Case study – Baby Theresa

This activity is taken from an exercise in E4J Ethics Module 1.

Students are presented with the following set of facts (the full details of the case are included in The Elements of Moral Philosophy by Rachels and Rachels, 2012):

Baby Theresa was born in Florida (United States of America) in 1992 with anencephaly, one of the worst genetic disorders. Sometimes referred to as “babies without brains”, infants with this disease are born without important parts of the brain and the top of the skull is also missing.

Most cases are detected during pregnancy and usually aborted. About half of those not aborted are stillborn. In the United States, about 350 babies are born alive each year and usually die within days. Baby Theresa was born alive.

Her parents decided to donate her organs for transplant. Her parents and her physicians agreed that the organs should be removed while she was alive (thus causing her inevitable death to take place sooner), but this was not allowed by Florida law. When she died after nine days the organs had deteriorated too much and could not be used.

The exercise suggests you encourage a discussion amongst your students around the following questions

How do we put a value on human life?

What should one do when there is a conflict between the law and one’s own moral position about an issue?

If you were in a position to make the final decision in this case, what would it be and why?

This case study provides a particularly emotive topic for discussion, which is not uncommon when dealing with issues of ethics. What techniques could you employ to ensure that your students engage positively with this discussion, despite the sensitive nature of the topic?

Answer

The answer to this question will depend upon your own particular teaching context, the size of the class and how well you know the group. When dealing with sensitive topics it can be helpful to depersonalise the issues and encourage students to explore points of view that they wouldn’t normally take.

One way of doing this is to allow students the opportunity to discuss the in small groups of three or four, before widening the discussion to the whole group. You then have the option of asking someone to report the ideas of the whole group which can avoid personalising the responses.

Alternatively, you could ask students, or small groups of students, to assume particular roles, or to argue for particular positions. For example, you could ask different groups to represent the views of parents, physicians and lawmakers. The rest of the group could then play the role of a jury where they are able to put questions to the groups before taking a vote on whether to allow the operation to take place.

4.3 Peer collaborative production

As students are listening to lectures, watching videos or reading texts that explain the core ideas of ethics to them, they gain a certain level of mastery over the material. But they will have mastery over different parts of it. One student might have a very strong command of Concept A but a fuzzy grasp of Concept B and find Concept C completely confusing.

By collaborating with his or her peer who is confused by Concept A but has a firm grasp of Concepts B and C, the student will be able to push him or herself and his or her peers into that zone of proximal development, thereby improving the learning of them both. The Modules thus provide plenty of recommended activities in which students work together on tasks, enabling them to help each other deepen their understanding of integrity and ethics.

One practical point about asking students to work collaboratively should be considered. Ideally, the students should work together to complete a concrete task of some kind. If you simply provide discussion questions for students, and invite them to discuss with one another, it is likely that the more motivated students will follow the directions, while the less motivated ones stray off task.

This problem can be avoided if the requirement is that students work collaboratively to produce something: a document, a list, a map, a performance, etc.

Activity 4.3 Ensuring clear outcomes for group tasks

Effective collaborative work requires that a group is tasked with producing a clear outcome. Bringing to mind your own teaching practice, what examples can you think of where you have enabled collaboration amongst your students by giving them a group task with a clear outcome?

Use the box below to note down at least one example.

Answer

Ensuring that student groups have a deliverable of some kind, even a very informal one, can be a very effective way of helping your students to learn collaboratively. There are many ways this can be done, and the E4J Modules use activities which embrace this approach.

For example, in E4J Anti-Corruption Module 6, students are introduced to a variety of ways to detect corruption. Exercise 3 of that Module asks students to consider how to tackle corruption by using blockchain technology.

The students are asked to watch a video explaining the blockchain technology and put into groups to prepare an anti-corruption plan. The students then present the work they have done to the class in a plenary session.

The following case study activity gives students the opportunity to help each other complete an initial learning activity, and then to present their work to the entire class. This basic structure works well for many types of collaborative activities and provides students with the opportunity to help each other learn.

Activity 4.4 Case study – Ethical business practices

Ethical business practices

This exercise is taken from E4J Ethics Module 7 (Strategies for Ethical Action)

In this exercise students are asked to imagine following situation:

You are working as an assistant to a manager of a company. Your company is bidding on a large, publicly tendered contract with a foreign government. After six months of expensive preparations and bidding, a government official assures you and the manager in a phone call that you will get the contract. Right before the contract is signed, someone from the government’s purchasing department requests a last-minute “closure fee”.

Your company needs this contract to reach its revenue target for this year. The manager decides to go ahead and pay the closure fee to get the contract. You notice that your company does not receive a receipt for the payment. You decide to check the tender provisions but you find no mention of an official closure fee.

You are convinced that the payment violates your company’s code of conduct and is indeed an act of corruption. You decide to go ahead and confront the manager, but the manager refuses to listen or discuss the matter. What sorts of excuses or rationalizations might the manager offer?

What techniques could you use to try to get your class engaged in discussing this issue?

Answer

The main objective of this exercise is to encourage students to train your students “moral muscle” and develop the skills in terms of the action-based approach to integrity and ethics.

Depending on your particular teaching context, and the time available, there are a number of ways you could approach engaging your students in this task. For example:

Part 1

Students are asked to discuss this question first in groups. Subsequently, the rationalizations discussed in the groups are discussed with the larger class.

Part 2

Groups are asked to pick one excuse or rationalization and to try to counter it by developing arguments to prove that the excuse is invalid. Students could be encouraged to make use of action-planning and script-writing techniques. In particular, they should be encouraged to build their argument so that it relates to personal beliefs and values, or to the values and codes of ethics of their organization. They should also consider which communication method to choose (e.g. formal, informal, written, or personal talk).

Depending on time, you can ask a couple of groups to present their counter arguments to the rationalization they chose.

Part 3

You ask your students to do a brief role-play in groups of two, where one student plays the manager putting forward the rationalization and the other student tries to voice his or her belief and counter the rationalization.

Of course, this sort of role-play should only occur after the entire group has engaged in ethical problem-solving (as above) and as also mentioned above, it is critically important to engage the students who are playing the manager who proposed the unethical action in helping to improve the approach used to encourage ethical action; this is essential as you don’t want to encourage rehearsal for unethical action and give the impression that the unethical response is just as good as the more values-driven approach.

Depending on time, a couple of groups may be chosen to play their interpretation in front of the class.

When conducting the exercise, you may wish to draw on the article Giving Voice to Values: How to Counter Rationalizations Rationally (Gentile, 2017).

While the dilemma situation in this exercise applies to the business context, it has the potential to be customized to fit other contexts that you consider appropriate for your students.

4.4 Conclusion

In unit 4 you have considered how encouraging social learning can help facilitate integrity and ethics education. In the next unit you will explore how and why developing self-awareness in students has been integrated into the learning activities.

Go to Unit 5: Becoming self-aware now.