Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 10:23 PM

Unit 13: Storytelling, comedy and popular culture

Introduction

Storytelling belongs first of all to an oral culture, which is not written down, remaining fluid, and relatively uncontrolled. When something is written down in a manuscript or a book, there is a standard against which other versions can be compared or corrected. Since the emergence of writing, political, social and religious institutions have privileged written records over oral memory and tradition.

This has had a huge influence on the survival and evolution of the Scots language. Having lost its role as a contemporary written language in the 17th century, Scots continued to thrive as a spoken tung. This led to Scots often being associated with aspects of culture that were not sanctioned by authority, or explicitly dissident. To gie tung or ‘raise your voice’ could be seen as anti-authority, an expression of cultural resistance and human freedom.

Consequently, people were told to curb or haud their tungs. And the forms of punishment administered by local courts included restraining the tongue, as for example with a Scold’s Bridle. In the Bridle the tongue is bitted, i.e. bitten or held in a metal brace. In extreme instances tongues were also removed, while another cruel physical punishment was the removal or cropping of lugs – the ears. Clearly all the organs of oral communication were targeted for repression, control and punishment. This was done to impose social order in communities where drunkenness and physical fighting were not uncommon.

Verbal abuse and flyting also came to the fore, which raised quarrels to a level of verbal skill and artistry. Until the 19th century travelling entertainers in Scotland – pedlar poets, storytellers and sangsters – were classified as vagrants and subject as social outcasts to restrictions on movement and settlement, and at times cruel restraints. The same regime applied to unlicensed beggars or sorners and to Scotland’s Travelling People – sometimes called Tinkers, ‘Gypsies’ or ‘Egyptians’.

However, such official disapproval could not prevent the general population continuing to sing and story in Scots, (though it did mean that such activities took place in unofficial venues: homes, taverns and around camp fires – rather than in school, church or tollbooth). Nonetheless, there is evidence that Scotland’s nobility continued to patronise poets, harpers, storytellers and even fools or jesters in the privacy of their castles and halls.

This may be why Scotland’s older traditions of oral song and story often feature the castle and the cottage, neglecting urban settings.

Important details to take notes on throughout this section:

- the resilience of oral storytelling

- the popularity of ‘kitchen ceilidhs’, ‘backgreen’ concerts, ‘speakeasies’ and ‘penny gaffs’ in the 19th century and onwards

- music halls and the dominance of English “in a Scottish accent”

- pantomime, television and comedy on stage.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

13. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: To scold, chide, rail; to altercate.

Example sentence: “They wid flyte oan the lood bairns tae haud yer tung.”

English translation: “They would scold the loud children to hold your tongue.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

They wid flyte oan the lood bairns tae haud yer tung.

Model

They wid flyte oan the lood bairns tae haud yer tung.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Related word:

Definition: To make angry, enrage; to trouble, annoy, bother, inconvenience.

Example sentence: “Dinnae fash yersel wi thon lassie – she’s buttoned up the back.”

English translation: “Don’t bother yourself with that girl – she’s daft.”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

“Dinnae fash yersel wi thon lassie – she’s buttoned up the back.”

Model

“Dinnae fash yersel wi thon lassie – she’s buttoned up the back.”

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

13.1 The resilience of oral storytelling

There is a need to qualify the term ‘oral’. As printing developed in Scotland, and literacy grew, a market opened up for cheap versions of songs and stories. These booklets were effectively folded sheets of print. The storytelling ones were often known as chapbooks and the ones with sung ballads as ‘broadsides’. These did not displace oral communication but they did feed into it.

The minority of the population who could read might memorise and then share these narratives, while many of the pedlars or chapmen who hawked them around Scotland performed their contents as a form of sales pitch. Some travelling professions such as tailors also became known for their storytelling abilities. In this way, Scots language material was sustained through print and oral memory.

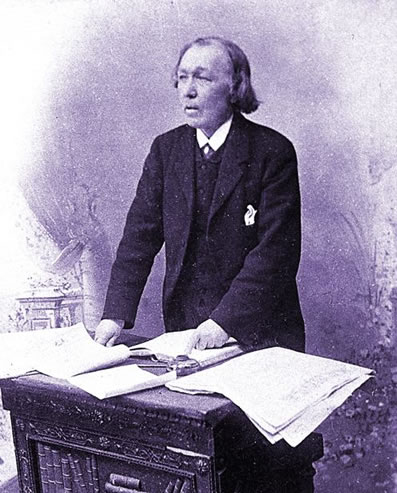

Something that survives only by oral transmission is, by definition, impossible to find before the onset of modern recording technologies. We do, however, have some precious records of oral performance. The following example comes from the memories of Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe from Hoddam in Dumfriesshire, written in later life in Edinburgh. Sharpe was a friend of Robert Chambers, who used Sharpe’s manuscripts in his Popular Rhymes and Traditions of Scotland (1870).

This book went through successive editions as Chambers went on collecting, but Sharpe’s memories of his Nurse Jenny’s storytelling were a valued element from the first edition of 1826 onwards.

Cultural links

In collecting and sharing Nurse Jenny’s stories in this way, Sharpe and Chambers were very much at the forefront of cultural developments happening across Europe.

In the early 19th century, many scholars of language and culture, such as the famous Brothers Grimm in Germany, had begun to recognise that folklore and the traditions of the ‘common’ people were the essential part of every culture. This came as a consequence of the rise of Romanticism during the 18th century, which had revitalised interest in traditional folk stories. To the Grimms and their colleagues, it represented an ‘uncorrupted’ form of national literature and culture, free from the influence of the ruling classes.

Like the Brothers Grimm, who collected and published folk tales and popularised traditional oral tales during the 19th century, Sharpe recoded the stories his Nurse Jenny had told him, including the way in which she made traditional stories and tales her own, adding embellishments, linking them to her local context – and last but not least – using her mother tongue, Scots, to convey them.

Activity 4

Part 1

Now work with an extract from Sharpe’s memories of his Nurse Jenny’s storytelling. To convey this oral tradition in the Scots language as authentically as possible, we want you to work with an audio recording rather than a written version of one of Jenny’s fairy stories.

Before beginning to listen, we suggest you look up the following words in the DSL, or you might also want to try the Online Scots Dictionary, as knowing the meaning of these words will help you follow the story better.

- caad (v.)

- kent (v.)

- aweel / weel (adv./adj.)

- weel sookit (adv./adj.)

- gae / gaes (v.)

- grys (n.)

- soo (n.)

- wolron (n.)

- moudiewart (n.)

Part 2

First of all, listen without reading the transcript and take some notes on what you think Nurse Jenny’s story is about.

As a second step, listen again while reading the transcript and compare your understanding with your notes.

Transcript

I never saw ane myself, but my mother saw them twice- ance they nearly droned her, when she fell asleep by the water-side: she wakened wi them ruggin ay her hair, and saw something howd down the water like a green bunch o potato shaws.

Memory has slipped the other story, which was not very interesting

My mother kent a wife that lived near Dunse- they caad her Tibbie Dickson: her goodman was a gentleman’s Gairdner, and muckle frae hame. I didna mind whether they caad him Tammas or Sandy- for his son’s name, and I kent him weil , was Sandy, and he-

Chorus of children: Oh never fash aboot his name, Jenny

Hoot, ye’re aye in sic a haste. Weel, Tibbie had a bairn, a lad bairn, just like ither bairns, and it thrave weel, for it sookit weel, and it & (Here a great many weels). Noo Tibbie gaes se day to the well to fetch water, and leaves the bairn in the house by itsel: she couldna be lang awa, for she had but to gae by the midden, and the peat-stack, and through the kailyaird, and there stood the well- I ken weel aboot that for (Here another long digression).

Aweel as Tibbie was comin back wi her water, she hears a skirl in her house like the stickin o a gryse, or the singin o a soo: fast she rins and flees to the cradle, and there I wat she saw a sicht that made her heart scunner. In place o her ain bonny bairn, she fand a withered wolron, naething but skin and bane, wi hands like a moudiewart, and a face like a paddock, a mouth frae lug to lug, and twa great glowrin een.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

Nurse Jenny’s fairy tale is about Tibbie Dickson, a mother who goes to fetch water from the well, and who, when coming home, finds that the fairies put a spell on her child, who has changed from a sweet looking boy to a skinny scoundrel with a huge mouth and scary eyes.

Language note

Chambers was a publisher based in London and Edinburgh which points to the fact that their publications were meant for an audience beyond Scotland. This had an impact on the way in which Scots language was represented in their publications.

Whilst it is likely that some aspects of the Scots pronunciation have been toned down in the written version in order to provide anglicised spellings sufficient to make the passage readable for both Scots and English speakers, Nurse Jenny’s story is rich in Scots vocabulary, and patterns of word order such as ‘I didna mind whether…’; or ‘she couldna be lang awa…’, which in English would be “I cannot remember whether…” or “she couldn’t have been away for long…”

You might want to find other examples of typical Scots tense forms of verbs and word order and comment on the Scots language features.

However, the principal point of interest is Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe’s recall of Jenny’s tale is its narrative style. This abounds in digressions linking personal memories and anecdotes to the main fairy tale. By weaving the fairy story into the everyday reality of herself and her audience, Jenny cleverly establishes a new platform of credibility on which the fairy world of fantasy can operate with the same credibility as going to the peat-stack. This unity of perspective is carried by the same use of language throughout, namely Scots.

Here is another example of Jenny’s narrative art, displaying an assured narrative flow, and a mastery of oral Scots vocabulary and idiom, the story of Whuppitiestourie.

The strange and questionable land of ‘Kittlerumpit’ has been anchored in Jenny’s own experience – and now that of her audience – through association with the real life episodes. We are ready to go wherever the tale takes us in Jenny’s accomplished storytelling flow. As it unfolds the tale is ‘Whuppitiestourie’ a distinctively Scots version of the international fairy story ‘Rumpelstiltskin’.

Activity 5

Part 1

As with the previous fairy tale, before listening, look up the following key words which will help your understanding of the Scots language used by Nurse Jenny:

- lily (adj.)

- gerse (n.)

- ane (adj., pron.)

- clatter (v.)

- vaguing (adj., n.)

- cleikit (v.)

- duleful (a.)

- limmer (n.)

- fendin / fend (v., n.)

- farra / farrow (adj.)

- listed (v.)

Part 2

Now listen to and enjoy Nurse Jenny’s version of Rumpelstiltsken. The use of song or verse to assist the story is both a sign of antiquity in the material but also of narrative skill in using different kinds of rhythm for variety and effect.

Humour is deployed throughout, whether applied to fairyland or the everyday world. These traditional stories are more than entertainment but without entertainment value, humour and suspense, they cannot function. Nor would they survive.

- a.What explanations does Nurse Jenny give as possible reasons for the disappearance of the goodman o Kittlerumpit?

- b.What was the one consolation for the gudewife o Kittlerumpit after her husband disappeared?

Transcript

Listen

I ken ye’re fond o clashes aboot fairies, bairns; and a story anent a fairy and the gudewife o Kittlerumpit has joost come intae my mind; but I canna very weel tell ye noo whereabouts Kittlerumpit lies. I think it’s somewhere in amang the Debatable Grund; onygate I’se no pretend to mair than I ken, like aabody noo-a-days. I wuss they wad mind the balant we used to lily langsyne:

Mony ane sings the gerse, the gerse,

And mony ane sings the corn;

And mony ane clatters o bold Robin Hood,

Ne’er kent where he was born.

But hoosoever, about Kittlerumpit: the goodman was a vaguing sort o a body; and he gaed to a fair ae day, and not only never came hame again, but never mair was heard o. Some said he listed, and ither some that the wearifu pressgang cleikit him up, though he was clothed wi a wife and a wean forbye. Hech-how! That dulefu pressgang! They gaed aboot the kintra like roaring lions, seeking whom they micht devoor. I mkind weel, my auldest brither Sandy was aa but smoored in the meal-ark hiding frae thae limmers. After they war gane, we pu’d him oot frae amang the meal, pechin and greetin, and as white as ony corp. My mither had to pike the meal oot o his mooth wi the shank o a horn spoon.

Aweel, when the goodman o Kittlerumpit was gane, the goodwife was left wi a sma fendin. Little gear had she, and a sookin lad bairn. Aabody said they war sorry for her; but naebody helpit her, whilk’s a common case, sirs. Howsomever, the goodwife had a soo, and that was her only consolation; for the soo was soon to farra, and she hopit for a good bairn-time.

Model

I ken ye’re fond o clashes aboot fairies, bairns; and a story anent a fairy and the gudewife o Kittlerumpit has joost come intae my mind; but I canna very weel tell ye noo whereabouts Kittlerumpit lies. I think it’s somewhere in amang the Debatable Grund; onygate I’se no pretend to mair than I ken, like aabody noo-a-days. I wuss they wad mind the balant we used to lily langsyne:

Mony ane sings the gerse, the gerse,

And mony ane sings the corn;

And mony ane clatters o bold Robin Hood,

Ne’er kent where he was born.

But hoosoever, about Kittlerumpit: the goodman was a vaguing sort o a body; and he gaed to a fair ae day, and not only never came hame again, but never mair was heard o. Some said he listed, and ither some that the wearifu pressgang cleikit him up, though he was clothed wi a wife and a wean forbye. Hech-how! That dulefu pressgang! They gaed aboot the kintra like roaring lions, seeking whom they micht devoor. I mkind weel, my auldest brither Sandy was aa but smoored in the meal-ark hiding frae thae limmers. After they war gane, we pu’d him oot frae amang the meal, pechin and greetin, and as white as ony corp. My mither had to pike the meal oot o his mooth wi the shank o a horn spoon.

Aweel, when the goodman o Kittlerumpit was gane, the goodwife was left wi a sma fendin. Little gear had she, and a sookin lad bairn. Aabody said they war sorry for her; but naebody helpit her, whilk’s a common case, sirs. Howsomever, the goodwife had a soo, and that was her only consolation; for the soo was soon to farra, and she hopit for a good bairn-time.

13.2 Humorous folk tales in Scots

Humorous folk tales such as those mentioned in section 13.1 continued to be told through the 20th century, mainly in rural areas, and among Scotland’s Travelling people. Here is a good example told by Traveller storyteller Betsy Whyte. This is a comic variant on the folk tale The Man or Woman Who Had No Story to Tell.

This tale is based on the idea that at a social gathering everyone attending would be supposed to ‘do a turn’ – tell a story, sing a song, play music or recite a poem. Failing that some adventure or mishap follows – involving, in this case, a sex change – so ensuring that in future the person concerned will have a story to tell!

One example of such a story is the tale of Jack the cattleman who was changed into a beautiful girl then back into himself, which you can listen to here.

However, this kind of do-it-yourself entertainment was not restricted to rural gatherings or Highland ceilidhs. It was also a feature of Scottish urban life, particularly from the 19th century when large numbers of poorer people migrated to cities in search of work. There were what might be termed ‘kitchen ceilidhs’ or ‘backgreen’ concerts and regular sessions in the back rooms of pubs, which became known as ‘speakeasies’.

In addition, there was a vigorous tradition of street entertainment, interacting with popular theatre performances in temporary venues known as ‘penny gaffs’. More middle class groups including church congegrations also organised paying concerts which used Scots stories, sketches and songs in more ‘respectable’ surroundings.

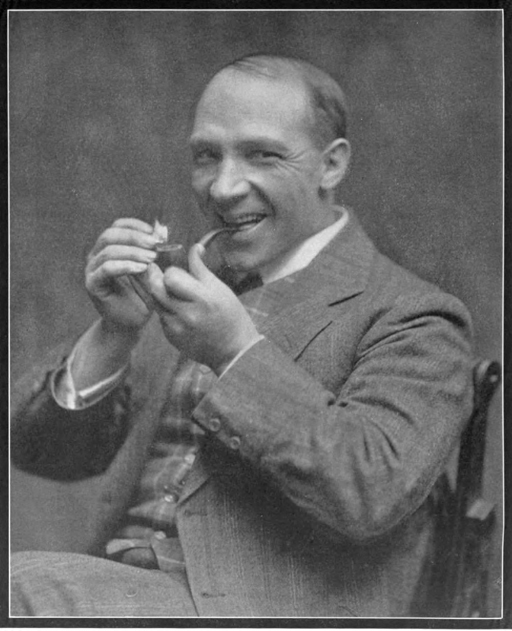

A poet and tragedian of Dundee, has been widely hailed as the writer of the worst poetry in the English language. A self-educated hand loom weaver of Irish descent, he discovered his discordant muse in 1877 and embarked upon a 25 year career as a working poet, delighting and appalling audiences across Scotland and beyond.

We know a bit about the lives of some of the performers who operated in these venues. William McGonagall’s performance poetry should be understood in the context of the penny gaffs, while William Houston was a successful performer on the politer circuits.

In Edinburgh, the Victorian writer James Smith (1824-1887) wrote for the popular entertainers. We are fortunate to have an example of his theatrical work, discovered in the Edinburgh Central Library and re-adapted for the stage by the modern playwright Donald Campbell, who was born in Edinburgh’s Cowgate, and who described it as a ‘found play’ (2007, p. 1).

This play, Nancy Sleekit (2007), is the story of an oft widowed and – if she is to be believed – much-put-upon lady, whom we meet first in mourning. The on-the-page text is a mixture of Scots and English spelling, reflecting James Smith’s, and then Donald Campbell’s editing, to ensure that the written version is comprehensible.

But the Scots strongly signals to a performer that every word and phrase will be shaped by Scots pronunciation and speech patterns.

Activity 6

Part 1

From the Nancy Sleekit extract below, identify a few English words included by the authors to ensure the written version was comprehensible for many, that you have seen the Scots spelling of in previous sections of this course.

I prefer weddings! That’s the even-doun truth, ye may think o’t what you like. I’m nane o yer mealy-moothed hypocrites that say ae thing and think anither – like a wheen o sour-faced auld fuffers that I ken. I like being mairriet, I’ve aye likit being mairriet. Nane o yer single blessedness for me!

Oh, it’s no that matrimony’s been sic a bonny bed o roses, that I likit the mairiet state sae weill – for God knows I had plenty to try me- by nicht and by day, for mony a year. I’ve been made a fair ringan devil when there was nae deevil in my heid –for my termpers’s as sweet as sugar candy when I get everything my ain way.

She sits down and takes another drink. She then opens the vanity case and takes out a cutthroat razor.

My first man was Tammie MacWiggie, a razor-faced, fiery-nosed barber, that I thocht was a perfect saint upon earth during our courtship – but there was never a greater draw-my-leg in creation. D’ye think he wad look at the very colour o blue ruination afore we were mairrit? No him! He preached and lectured on the horrors o drink in sic an eloquent manner that it actually made me greet! ... Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!

Answer

This is a model answer. Your selection of words might be different.

- sour - soor

- for - fir

- to - ta/tae

- devil - deil

- myself - myself/masel

Part 2

Now listen to the extract from Nancy Sleekit you have worked with in Part 1. You might want to read it out loud alongside the recording to practise your spoken Scots.

Transcript

Listen

I prefer weddings! That’s the even-doun truth, ye may think o’t what you like. I’m nane o yer mealy-moothed hypocrites that say ae thing and think anither – like a wheen o sour-faced auld fuffers that I ken. I like being mairriet, I’ve aye likit being mairriet. Nane o yer single blessedness for me!

Oh, it’s no that matrimony’s been sic a bonny bed o roses, that I likit the mairiet state sae weill – for God knows I had plenty to try me- by nicht and by day, for mony a year. I’ve been made a fair ringan devil when there was nae deevil in my heid –for my termpers’s as sweet as sugar candy when I get everything my ain way.

She sits down and takes another drink. She then opens the vanity case and takes out a cutthroat razor.

My first man was Tammie MacWiggie, a razor-faced, fiery-nosed barber, that I thocht was a perfect saint upon earth during our courtship – but there was never a greater draw-my-leg in creation. D’ye think he wad look at the very colour o blue ruination afore we were mairrit? No him! He preached and lectured on the horrors o drink in sic an eloquent manner that it actually made me greet! ... Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!

Model

I prefer weddings! That’s the even-doun truth, ye may think o’t what you like. I’m nane o yer mealy-moothed hypocrites that say ae thing and think anither – like a wheen o sour-faced auld fuffers that I ken. I like being mairriet, I’ve aye likit being mairriet. Nane o yer single blessedness for me!

Oh, it’s no that matrimony’s been sic a bonny bed o roses, that I likit the mairiet state sae weill – for God knows I had plenty to try me- by nicht and by day, for mony a year. I’ve been made a fair ringan devil when there was nae deevil in my heid –for my termpers’s as sweet as sugar candy when I get everything my ain way.

She sits down and takes another drink. She then opens the vanity case and takes out a cutthroat razor.

My first man was Tammie MacWiggie, a razor-faced, fiery-nosed barber, that I thocht was a perfect saint upon earth during our courtship – but there was never a greater draw-my-leg in creation. D’ye think he wad look at the very colour o blue ruination afore we were mairrit? No him! He preached and lectured on the horrors o drink in sic an eloquent manner that it actually made me greet! ... Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!

When the piece was revived for the modern stage in 1994, Nancy was played by Anne Louise Ross, a well-known Scots actress, whose natural command of Scots idiom informed her interpretation of the text throughout. Though such re-staging can only throw an experimental light on the past, the evidence clearly suggests that a rich urban Scots was the default linguistic medium for popular urban entertainment in the 19th century.

And this accords with the printed evidence from chapbooks, broadsides and the weekly newspapers, whose circulation increased steadily with each decade from the 1800s onwards.

As the monologue in the play develops, Nancy is revealed as a serial disposer of inconvenient husbands. In the process, she sends up traditional Victorian pieties of house and home, and gender stereotypes, reinforcing the sense that oral Scots continued as a vehicle for social satire.

Religion, romantic sentiment, and the trappings of respectability, which were supposed to be the essence of Scottish Victorian culture, are resolutely undercut by Nancy’s sly and reductive realism in the play. You’ve seen an excellent example of this realism concluding the extract from Activity 6: ‘Sae I gied him my hand and my hairt, in aa the gowden prime o maidenly innocence. I fair thocht myself in Paradise – for the first fortnicht!’

13.3. Music halls and the dominance of English

Penny gaffs and speakeasies were very popular but their success also sowed the seeds of their undoing. The city authorities began to impose licensing restrictions, and this led to the growth of larger, better organised, venues – the music halls. Initially the audiences for the music hall acts were local and the already successful staples of Scots comedy such as over-kilted Highlanders, interfering spinsters and village worthies continued to provide an outlet for satiric representations of Scottishness.

But the music halls were paying venues which attracted a much wider clientele than the non-paying speakeasies, and the business acumen of their managers led to organised touring circuits, including overseas tours. The foundation of the hugely successful international business of Variety Theatre had been laid.

Performers such as W.F. Frame were among the first to make this transition from the local speakeasy to an international stage. Here he is in 1898 opening a show for emigrant Scots in the Carnegie Hall in New York with a verse monologue ‘Brither Scots, When Freens Meet He’rts Warm’ (Frame, 1905 p. 93–94):

I’m here the nicht, faur frae the shore,

Faur frae the land we a’ adore-

The land that gied oor faither’s birth,

The dearest land on a’ the earth;

Whaur bonnie grows the purple heather-

Whaur some o’ us were boys together,

The land o’ yours, the land o’ mine;

An you revere it, weel I ken,

Scottish women, Scottish men.

Who ne’er forget, though great or sma’,

The freens in Scotland far awa’.

Auld Scotland’s sons frae ower the seas-

Men frae rocky Hebrides;

Men frae the mountain and the glen;

Men wha can wield the sword and pen’

Frae the Hielans, Lowlands, don’t forget

That Scotland is auld Scotland yet.

That land that’s faur across the wave,

The land whaur there is many agrave;

Graves that haud both yours and mine-

Freens o’ oor youth, o’ sweet lang syne.

Activity 7

In this activity you will consider how the Scots language of W.F. Frame’s monologue has changed in comparison with the quotes from earlier storytelling in Scots language, which you have studied previously in this unit.

Read the monologue ‘Brither Scots, When Freens Meet He’rts Warm’ and pay particular attention to:

- the perspective on Scotland displayed here

- the amount of Scots vocabulary used

- the use of rhyme for performance purposes.

Then write a short summary of your findings.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

It is clear that Frame is looking at Scotland – together with his audience – from a distance. The perspective on Scotland has become hazy, stereotyped but also misty eyed and romanticised. The Scots language content has thinned and English language is taking on an even more prominent role. This might have been done in an effort to ensure the monologue would be understood by the New York audience.

Yet, this had an impact on the role Scots played in the monologue overall – it became somewhat decorative, whereas English takes over as a structural element. This can be seen for example in the use of ‘together’ for ‘thegither’ in order to allow a rhyme with ‘heather’. In general standardised sub-poetic English is used to provide the rhythm and rhyme as in ‘shore’ and ‘adore’. Scots words are scattered within an English structure to give a flavour of Scottishness.

The tone of the monologue you read in Activity 7 is sentimental recall of a distant place, which only becomes close through emotion. The question remains, in what way the satiric humour, previously a key element of storytelling in Scots, is still playing a part in Frame’s monologue.

The lines following what you have read above, recover a sense of spoken Scots idiom, but only to exhibit it as quaint and couthy. This can be seen in the rhymes, which are still dominated and dictated by English, as well as in the repetitions, which give the monologue the character of a children’s poem or song.

But stop a wee, wheest, haud yer tongue.

Noo whether auld or whether young,

We like a laugh, we like a joke,

We like a sang, like a’ Scotch folk:

We like a crack- an oor or twa-

Aboot the days that’s long awa’…

We’ll just imagine we’re at home-

Back tae dear auld place again;

Back ta ethe toon, back tae the fairm;

Back tae the guid auld harum scarum.

But, hoots, I think I’ve said enough,

My very tongue is getting touigh.

So if you please, jist touch thae keys,

An’ at my ease, tae tell nae lees,

I’ll sing a song, and tell a wheeze.

This is carefully crafted to appeal to an emigrant audience, but the attitudes and emotions expressed soon became indicative of ‘Scottishness’ in a period when despite its industrial success Scotland had no distinctive political or cultural status.

Other famous names were to follow Frame, including the music hall artist from Dundee, Will Fyffe, the gifted comic who wrote ‘I Belong to Glasgow’, and pre-eminently Harry Lauder, the Edinburgh-born singer and comedian who achieved international success.

Activity 8

In this activity you will work with one of Lauder’s most famous songs, ‘Wee Deoch an Doris’. The phrase ‘deoch an doris’ is Gaelic and means a parting drink offered to guests, ‘one for the road’. It is interesting how Lauder mixes Gaelic and Scots in the heading by adding the adjective wee to the Gaelic phrase, all in an effort to create a sense of ‘Scottishness’.

Listen to the song performed by Harry Lauder.

While listening, read the lyrics below. When reading and listening to the lyrics of this song, pay particular attention to when and how Scots language is used here.

You may also want to compare Lauder’s use of the Scots language with how Frame used Scots in his monologue.

There's a good old Scottish custom that has stood the test o' time,

It's a custom that's been carried out in every land and clime.

When brother Scots are gathered, it's aye the usual thing,

Just before we say good night, we fill our cups and sing..

Chorus

Just a wee deoch an doris, just a wee drop, that's all.

Just a wee deoch an doris afore ye gang awa.

There's a wee wifie waitin' in a wee but an ben.

If you can say, "It's a braw bricht moonlicht nicht",

Then yer a'richt, ye ken.

Now I like a man that is a man; a man that's straight and fair.

The kind of man that will and can, in all things do his share.

Och, I like a man a jolly man, the kind of man, you know,

The chap that slaps your back and says, "Jock, just before ye go..."

Chorus

I'll invite ye a' some other nicht, to come and bring yer wives.

And I'll guarantee ye'll have the grandest nicht in all yer lives.

I'll have the bagpipes skirling

We'll make the rafters ring.

And when yer tired and sleepy, why I'll wake yer up an' sing:

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

The process begun by Frame goes further here with the dominance of English ‘in a Scottish accent’. What is even more interesting though is the use of Scots and a kind of ‘pidgin Gaelic’ in the chorus. Everything is ‘wee’, and Scots has become something you say or sing when drunk. This is not so much using Scots, as exhibiting it as a linguistic marker of cultural stereotypes.

Of course, Lauder is well aware they are stereotypes and deploys them for comic effect, for example in the line: The chap who slaps your back and says “Jock, before you go”. But the humour is superficial, a back-slapping endorsement of something that lacks social reality or emotional truth.

13.4 From Leonard to Bissett

The Music Halls and the burgeoning Variety Theatres were at their peak in the early 20th century, and Variety survived the setback of Word War to influence early film and subsequently television entertainment. In addition, one form of Variety Theatre, Pantomime, was to emerge as the most enduring and successful form of live theatre in Scotland throughout the century.

However, the trajectory of Scots language was different, as a new literature-led Scots language renaissance began in the 1920s, gathering momentum in the 1930s. Richer Scots, with varying relationships to diverse forms of spoken Scots, was heard on small and then larger stages featuring in new, more realistic dramas.

As regards popular entertainment, the key factor was that many performers using Scots language moved between drama productions, Variety, Pantomime, and subsequently television. Versatile actors such as Duncan Macrae, Rikki Fulton, and Stanley Baxter, for example, survived and thrived by combining these different arenas and in the process they deployed a sophisticated understanding of spoken Scots in different social registers and contexts.

Some of this story belongs to theatre in its own right, but it is important to remember that Duncan Macrae could play the lead in Robert McLellan’s ‘Jamie the Saxt’ (1971) and perform ‘The Wee Cock Sparra’ at Hogmanay. Rikki Fulton formed a comic twosome with Jack Milroy as the hilarious Glasgwegians ‘Francie and Josie’, but he was also a master of stage Scots in Molière adaptations such as Robert Kemp’s ‘The Laird o’ Grippy’ (1987).

Stanley Baxter revelled in Scots linguistic diversity in his ‘Parliamo Glasgow’ broadcasts while also excelling as a pantomime dame and a straight actor.

Activity 9

In this activity you will be working with the text of Duncan Macrae’s ‘A Wee Cock Sparra Sat on a Tree’, which he adapted from an oral version which he heard recited in a student revue.

Read text and note down three examples of rhyme and repetition that give this piece its distinctive character.

A wee cock sparra sat on a tree,

A wee cock sparra sat on a tree

Chirpin awa as blithe as could be.

Alang came a boy wi'a bow and an arra,

Alang came a boy wi'a bow and an arra,

Alang came a boy wi'a bow and an arra

And he said: 'I'll get ye, ye wee cock sparra.'

The boy wi' the arra let fly at the sparra,

The boy wi' the arra let fly at the sparra,

The boy wi' the arra let fly at the sparra,

And he hit a man that was hurlin' a barra.

The man wi' the barra cam owre wi' the arra,

The man wi' the barra cam owre wi' the arra,

The man wi' the barra cam owre wi' the arra,

And said: 'Ye take me for a wee cock sparra?'

The man hit the boy, tho he wasne his farra,

The man hit the boy, tho he wasne his farra,

The man hit the boy, tho he wasne his farra

And the boy stood and glowered; he was hurt tae the marra.

And a' this time the wee cock sparra,

And a' this time the wee cock sparra,

And a' this time the wee cock sparra

Was chirpin awa on the shank o' the barra.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

Three examples are:

- the signature line: A wee cock sparra – it is at the beginning of the line, it is thus more prominent

- the last line of one verse is also the first of the next, for example: Alang came a boy wi'a bow and an arra

- there is one rhyming feature that runs through the entire song, words with ‘rra’ in them: arra, sparra, barra, farra and marra – all words which are linked very strongly with the Glaswegian dialect of Scots and which function here as a linking element in all verses

With this piece we are back in the world of kitchen ceilidhs and speakeasies – note the cumulative repetitions allowing for multiple comic effects in performance. But Macrae carried this piece of exuberant nonsense off on huge variety stages and on television, because his skillful use of Scots resonated with contemporary spoken usage. Unlike some of the literary Scots in straight theatre, the spelling and pronunciation runs the words together to reflect in a heightened way of natural rhythms in urban speech.

It is interesting to see popular artists like Macrae anticipating some of the linguistic experiments that were carried forward by Tom Leonard and James Kelman in written literature. Their point was that contemporary Scots was not a parochial dialect to be looked down upon but a language in its own right, deserving of respect and expression, humorous and serious.

Tom Leonard articulates that point ironically in a poem ‘Parokial’ that employs his favoured monologue form – like the actors and comedians you came across before in this unit.

Activity 10

By the 1970s these streams of change were coming together in a confident and diverse use of spoken Scots across the arts and the broadcast media. The era of Billy Connolly, Dorothy Paul, Gregor Fisher, and Elaine C Smith had begun. Billy Connolly is especially significant in these developments because his career, like those of Will Fyffe and Harry Lauder, was to bridge any divide between his home following and international audiences.

Here is a video of one of Billy Connolly’s set-pieces, ‘The Crucifixion’. Listen carefully not just to the story but to the language in which it is expressed. The opening is low key and in standard English though spoken in a Scots accent.

“This is the story….and it’s about a girl in Glasgow who worked in a printing works and made a terrible misprint one day in the Bible. Because of her misprint people to this day think the Last Supper in The Saracen's Head Inn was in Galilee, but in actual fact it was in Gallowgate - near the cross. Near the cross!”

However, as soon as Connolly voices one of the characters in direct speech the language is contemporary urban Scots: “Gie us anither gless o wine……You telt me the Big Yin wis comin in…..Ah’m knackered..…Hope he gies us wan o thae stories….Big Yin, he’s steamin,” and so on. Even more striking however, is that Jesus also speaks in demotic Scots: “See you, Judas, you’re getting ontae ma tits……..Wan o yous’s goin shop me.” (our transcript of https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8WgXPBDrd8s)

Then well into the piece, Billy Connolly starts narrating not in the third person (“he did…she did”) but in the first person as Jesus himself. In this way, the Scots voices become the defining reality markers of the whole narrative. This is agile storytelling because the unobtrusive shift of focus lends authority to the first person experience, in Scots, while also making that voice the expression of the external authority figure of Christianity - Jesus Christ.

In this way, Billy Connolly challenges the conventional norms of the community in which he was brought up, though in actuality the end effect may be more to humanise than denigrate the crucifixion story. The misprint in that canonical record, the Christian Bible, has concealed more than a question of locality - in the end it is about meaning, and of course the language which conveys meaning.

Very similar issues feature in a more recent Billy Connolly piece, in which he reacts to the Terrorist attack on Glasgow Airport in March 2011, which was thwarted by the actions of staff and public – most notably John Smeaton, the baggage handler. Connolly’s account preferences the speech and attitude of Smeaton in contrast to the metropolitan media, who are puzzled by the local response, and baffled by his answers to their questions. Clearly it is the local Glasgow perspective that has made the vital difference, and Connolly is proud to articulate that to his international audience. For this moment his own hometown is in the limelight, in a way that affirms its values and perspectives.

Another contemporary writer and performer who builds on these approaches is Alan Bissett. His work is interesting because it is rooted in his native Falkirk in the East of Scotland, showing with his work that Glasgow is part of a wider urban Scots context.

Here is the opening of The Moira Monologues which were produced in 2009, with (More) Moira Monologues following in 2017.

I dinnay gie a FUCK if yer man’s a bouncer!

Yer dug’ll no go near ma dug again. Or ken whit I’ll dae? Wantae ken whit I’ll dae tae it?

I’ll take its baws and I’ll squeeze them like that and see by the end?

It’ll look like its shat oot twa fuckn Pepparami.

And ken whit she says tae me, Babs?

Ken whit the cheeky cow actually says?

I’ll be phonin the Cooncil about you, Moira Bell!

I’m sick and tired ay your cerry-oan, Moira Bell!

Alan Bissett again brings together the popular comic and the literary stage through Scots, while he himself thrives as both a writer and a performer. Storytelling, Comedy and Popular Culture is a continuing story for Scotland, with the Scots language continuing to be centre stage. Certainly, Moira Bell’s ‘tung’ is no longer bitted in a scold’s bridle.

13.5 What I have learned

Activity 11

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- the resilience of oral storytelling

- the popularity of ‘kitchen ceilidhs’, ‘backgreen’ concerts, ‘speakeasies’ and ‘penny gaffs’ in the 19th century and onwards

- music halls and the dominance of English “in a Scottish accent”

- pantomime, television and comedy on stage.

Further Research

Explore the work and offers of the Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh.

This recording of The Pipers from 1904 gives you an impression of W.F. Frame’s performance style.

You may want to explore further the notion of ‘Scottishness’, which you have come across in this unit, for example, with this study by the University of Manchester based on the 2011 Census, or this YouGov survey on ‘What makes a person Scottish’.

Here you can explore W.F. Frame’s life by reading his bibliography W.F. Frame The Man you Know in the original edition.

The find out more about Harry Lauder, explore this page of Glasgow University’s Special Collections.

Find out more about the pantomime tradition in Scotland in this article in The Scotsman.

Want to hear one comedian’s views on another? Read this insightful piece by John Scott on Billy Connolly's Billy Connolly…and the Crucifixion.

Now go on to Unit 14: Scots and the history of Scotland.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Rogue One Mural: Daniel Naczk https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Glasgow._Braehead_Tunnels._Graffiti._Oor_Wullie.jpg. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Witch Winnie image: Champney, Elizabeth W. (1890) Witch Winnie, the story of a "king's daughter;" Edinburgh, O. Anderson & Ferrier

Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe painting: Thomas Fraser, Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, c 1781 - 1851. Antiquary, Gifted by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 2009, National Galleries of Scotland, https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/8877/charles-kirkpatrick-sharpe-c-1781-1851-antiquary

Extract from Nancy Sleekit: Campbell, D. (2007) Nancy Sleekit and Howard’s Revenge. Fairplay Press

Poem in Activity 9: Duncan MacRae

Photo of Billy Connolly Mural: Bruce Eunson

Extract from The Moira Monologues: Bissett, A. (2015) Moira Monologues in Collected Plays 2009-2014. Freight Books