Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 10:49 PM

Unit 11: History and linguistic development of Scots

Introduction

In this section you will learn what the Scots Language is, and how the Scots Language developed from the Middle Ages through to the present day. You will see how the language has changed over the centuries, and you will be able to read and compare short examples of written Scots from different historical periods. You will learn about how the status of Scots changed at different points in Scottish and British history. This unit also introduces you to some short extracts from the work of some of the best-known literary writers who have used Scots.

Important themes to take notes on throughout this section:

- what the Scots Language is, and why it is considered a language in its own right

- how Scots emerged as the official language of the state during the Middle Ages; poetic and literary ‘high culture’ associated with the language during the Middle Ages

- the use of Scots during Renaissance and Reformation times

- the changing fortunes and status of Scots during the 17th and 18th centuries, including linguistic Anglicisation and the 18th century ‘Vernacular Revival’

- the perseverance of the Scots language during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

11. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: to cause to rotate or spin, to turn, twirl.

In Orkney in particular, the word has changed its meaning slightly in recent decades, and is now used to refer to any modern wind turbine. The word derives from the Scots verb tirl, meaning to rotate, and has the additional diminutive ending ‘…ick’:

Example sentence: “Jist aboot every ferm in Orkney and Shetland his its own tirlick noo.”

English translation: “Nearly every farm in Orkney and Shetland has its own wind turbine now.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Jist aboot every ferm in Orkney and Shetland his its own tirlick noo.

Model

Jist aboot every ferm in Orkney and Shetland his its own tirlick noo.

Related word:

Definition: Evening twilight, dusk.

Example sentence: “Yon photo abun shaas the gloamin...”

English translation: “That photo above shows the evening twilight...”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Yon photo abun shaas the gloamin...”

Model

Yon photo abun shaas the gloamin...”

Language Links

The Scots noun gloamin(g) has an interesting and very long history, and exists in a range of different languages where it is used as a noun or a verb – yet all its meanings in the different languages have to do with exuding light that can also look like fire. Older Scots has used the words glo(a)ming, glowming, etc. from around 1420 to describe evening twilight or dusk. The Old English language used glōmung, meaning twilight.

A derivation of this also exists in the German language today, the noun or verb glühen, meaning to glow or slowly burn. In Old High German the verb gluoen, with this meaning, was used in the 9th century. In the Middle Ages this verb appeared in a variety of Germanic languages as glüe(je)n, glüewen, glōian, glöyen, gloeyen, orglōyen. In Dutch we find the verb as gloeien.

11.1 What the Scots language is, and what it is not

The Scots language is one of three indigenous languages of Scotland. Scotland’s other indigenous languages are English and Gaelic. English is used throughout Scotland, while Gaelic is used mostly in the Highlands and the Western Isles. Scots is spoken throughout the Lowlands, in the Scottish cities, and in the Northern Isles.

Scots has often been misunderstood as 'slang', as corrupt or inferior English, or as a dialect of English. Following the ratification by the UK Government in 2000 of the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages, most academics are now in agreement that Scots is a Germanic language in its own right, and that it is a sister language to English, with which it shares a common ancestor in dialects of Old English.

It hasn’t always been appreciated that Scots has some 60,000 unique words and expressions, that it is the language of a magnificent, centuries-old literature, or that it was once a language of state used by kings, politicians and ordinary people alike.

There are many different varieties of Scots. Some of these have local names of their own, and they are sometimes known as ‘dialects’. It is important not to confuse dialects of Scots with dialects of English, or to imagine that Scots is a dialect of English. So, the dialects of Caithness, Orkney or Shetland are varieties of Scots. The language used in the North East of Scotland and known as the Doric is a variety of Scots.

Scots is also the name that we use for the distinctive language used in the cities of Dundee, Edinburgh or Glasgow. Scots is the name for the language used in parts of Dumfries and Galloway, in Ayrshire, or in the Scottish Borders. In the 2011 Scottish Government census, about a million and a half people reported that they use and understand Scots to some degree.

As the linguist Max Weinreich famously put it: ‘A language is a dialect with an army and a navy’, meaning that the distinction between a ‘language’ and a ‘dialect’ is largely a political distinction. Scots has a vast range of vocabulary, a long history, a wide variety of unique grammatical features, a huge store of idiomatic expressions, and a number of sounds that are never used in English.

For these reasons, most linguists and academics agree that Scots is a language in its own right.

Activity 4

In this activity you will establish what makes Scots a language in its own right. Although the distinction between a ‘language’ and a ‘dialect’ is largely a political distinction, there are characteristics that help you distinguish a language in its own right.

According to the information in the text above, which statements are true and which are false?

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

False

b.

True

The correct answer is a.

a.

False

b.

True

The correct answer is a.

a.

False

b.

True

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

11.2 Scots in the Middle Ages

The Scots Language came into being – and came into its own – during the Middle Ages. It was at this time that what had been a northern variety of Old English developed into distinct and recognisable Scots, and took over from Gaelic as the main language spoken by the monarchs, the nobles and the peasants of Lowland Scotland.

By about the year 1450, Scots had supplanted Latin as the main language for all official documents and nearly all literary writing in Scotland. The language of state in Scotland during the Middle Ages was Scots, and from the year 1462, the statutes – or laws – of the Scottish Parliament were recorded in Scots.

Activity 5

In this activity, you will consider what form the public reaction would take if the Scottish Parliament today were to return to writing laws and official communications in Scots. You will work with a colourful example from the reign of James IV, which is an extract from the Statues of the Scottish Parliament from 18th February 1490, addressing malpractice among goldsmiths.

- a.Listen to the extract and establish what the goldsmiths were accused of doing wrong as well as what the parliament decreed to put an end to this malpractice. As always, try to listen first without reading the transcript at the same time.

- b.Then compare your notes with the translation in the answer. Can you spot some characteristics of Old Scots as opposed to the Scots you have come across in part 1 of this course?

Transcript

Item, as tuiching the articule of goldsmythtis, quhilkis layis and makkis false mixtouris of ewill metale, coruppand the fyne mettall of gold and silver in dissate of oure soverane lord and his liegis that gerris mak werkkis of golde and silver, for reformacioune and eschewing of the sammyn, it is now avisit and concludit that na goldsmythtis sall mak mixtour nor put false layis in the said mettallis.

Answer

a.The goldsmiths were found to mix gold and silver with other metals and claiming these mixtures to be gold and silver, thus misleading their clients such as the King.

To tackle this malpractice, goldsmiths were from the date of the declaration onwards forbidden to produce mixtures of gold and silver with other metals.

b.Translation:

Item, as touching the article of goldsmiths, who debase and make false mixtures of bad metal, corrupting the fine metal of gold and silver, deceiving our sovereign lord and his lieges who have them create pieces in gold and silver, for the remedy and eschewing of the same, it is now advised and concluded that goldsmiths shall not make mixtures or put false alloys in the said metals.

Some linguistic features of Older Scots to note here include the plural forms of nouns which end in ‘…is’ (“Goldsmithis’, ‘mixtouris’); the ‘…and’ ending for present participles (“coruppand’); the use of the spelling ‘quh…’ for ‘wh’ at the beginning of certain pronouns or interrogatives; and the use of ‘mak’ or ‘makkis’ for ‘make’ or ‘makes’.

Much of the great literature of the Middle Ages in Scotland was connected to the royal court. Many of Scotland’s monarchs were themselves poets, or ‘makars’, as they are known in Scotland. James I was Scotland’s first poet king. While he was imprisoned in England during the early 15th century James wrote a long Scots poem called The Kingis Quair (The King’s Book).

The Scottish monarchs promoted cultural activity by employing court poets, who would write poems on all kinds of topics. These poems would then be performed for the entertainment of the court.

The most celebrated of the medieval makars was William Dunbar, who was the court poet of King James IV. Dunbar was able to produce beautiful devotional poetry on the one hand, and shocking yet hilarious, vulgar verbal duels, or ‘flytings’, on the other.

Activity 6

Dunbar was unusual as a medieval poet because he sometimes wrote about quirky or personal topics, as in this verse from a poem about a recurrent migraine.

Part 1

Listen to the verse and try to understand what effects of migraine Dunbar describes. Also read out the verse and record yourself, then compare your recording with Jeremy Smith reading.

Transcript

Listen

My heid did yak yester nicht,

This day to mak that I na mycht,

So sair the magryme dois me menyie,

Perseing my brow as ony ganyie,

That scant I luik may on the licht.

Model

My heid did yak yester nicht,

This day to mak that I na mycht,

So sair the magryme dois me menyie,

Perseing my brow as ony ganyie,

That scant I luik may on the licht.

11.3 Scots in Renaissance and Reformation times

By the second half of the 16th century, the Scots language was beginning to change, largely in response to developing links to England. The Reformation of the Catholic Church in Scotland during the 1550s and 60s was a tumultuous time, yet it was also a time of extensive cultural activity. Following in Martin Luther and the German Reformation’s footsteps, where the New Testament was first published in German in 1522, a ‘vernacular’ Bible, which was written in English and known as the Geneva Bible, was adopted by religious reformers in Scotland. This made the Bible accessible to anyone who could read, but also meant that many people were reading English, rather than Scots.

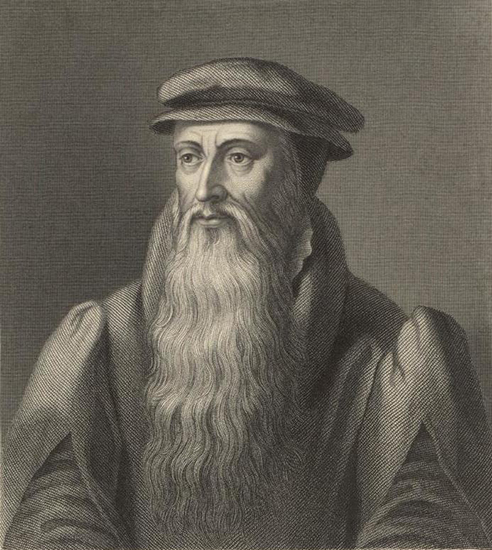

The leader of the Reformation in Scotland, John Knox, wrote a lengthy History of the Reformation (1559–1566) in lively Scots prose. Knox’s writing is very much of its time and is well known for its outrageous prejudice against women and Catholics.

Activity 7

In this activity you will be working with an extract from Knox’s History of the Reformation, in which he ridicules two cross bearers who come to blows while leaving Glasgow Cathedral. These events are thought to have taken place on 4th June 1545.

Part 1

Listen to the extract and try to understand what events took place according to Knox. Try to listen first without looking at the transcript. Also read out the verse and record yourself, then compare your recording with our model.

Transcript

Listen

Cuming furth att the qweir doore of Glasgw Kirk, begynnes striving for state betuix the two croce beraris, so that from glowmying thei come to schouldering; frome schouldering, thei go to buffettis, and from dry blawes, by neffis and neffelling; and then for cheriteis saik, thei crye Dispersit, dedit >pauperibus, and assayis quhilk of the croces war finest mettall, which staf was strongest, and which berar could best defend his maisteris preeminence; and that thare should be no superioritie in that behalf, to the ground gois boyth the croces. And then begane no litill fray, but yitt a meary game; for rockettis war rent, typpetis war torne, crounis war knapped, and syd gounis mycht have bene sein wantonly wag from one wall to the other: Many of thame lacked beardis, and that was the more pitie; and therefore could not bukkill other by the byrse, as bold men wold haif doune.

![]()

As you go on to explore the relationship between Scots language and Scottish history in more depth, you may like to consider whether or not James’ departure for London was truly a ‘hammer blow’ to the Scots language, or whether the language has proved to be more tenacious and resilient than the term suggests.

Has Scots gone ‘underground’?

Is it ever likely to enjoy a revival for formal or official purposes?

11.4 Scots language in the 17th and 18th centuries

The 17th century is sometimes regarded as a sad and quiet period in the history of Scots language and literature. James VI had left for London, golf clubs swinging from the back of his carriage, taking his band of talented court poets with him. William Drummond of Hawthornden remained almost as a sole literary figure, writing his lonely, anglicised poetry at home in Scotland. Elizabethan English entered a flourishing golden age as James sponsored the work of William Shakespeare in the south.

As time went on, and despite the relocation of the royal court and the subsequent dissolution of the Scottish Parliament at the point of Union in 1707, the city of Edinburgh was to emerge during the 18th century as the centre of a great upsurge in scientific, economic and philosophical learning which became known as the European Enlightenment.

Many of the leading figures of this Enlightenment were Edinburgh Scots, natural communicators in Scots language. Their language became a source of embarrassment and insecurity for them as they sought to please southern readers and associates. David Hume famously and obsessively checked the manuscripts of his great works to identify and eradicate rude lexical or grammatical ‘Scotticisms’.

The Scottish aristocrats of the 17th and 18th centuries sent their sons to be privately educated in England, where they learned the southern language, which came to be regarded as ‘polite’ or ‘refined’. ‘Elocution’ lecturers plied a lucrative trade, capitalising on linguistic snobbery and cultural insecurity that survives to this day.

But the Scots Language wouldn’t disappear. The great city poet Robert Fergusson published his vibrant, learned Edinburgh work in flamboyant Scots. The young Robert Burns was to visit Fergusson’s grave, and kiss the soil. These two poets were at the heart of what became known as the ‘Vernacular Revival’ of the late 18th century, with Burns in particular becoming the world’s most famous poet – and writing his greatest poetry in braid Scots.

Activity 8

In this activity you will work with an extract from Burns’ ‘Address to the Deil’ (1785) that highlights how the poet was able to use his Scots to bring together philosophical and religious thought with elements of the folk tradition - and all in the language of Lowland Scotland.

Part 2

Listen to the first two verses of Burns’ poem. Then record yourself reading these lines out and compare your pronunciation with that of our model.

Transcript

Listen

O Thou, whatever title suit thee! Auld Hornie, Satan, Nick, or Clootie! Wha in yon cavern grim an sootie, Clos’d under hatches, Spairges aboot the brunstane cootie, To scaud poor wretches!

Hear me, auld Hangie, for a wee, An let poor, damned bodies bee; I’m sure sma pleasure it can gie, Ev’n tae a deil, To skelp an scaud poor dogs like me, An hear us squeal!

Model

O Thou, whatever title suit thee! Auld Hornie, Satan, Nick, or Clootie! Wha in yon cavern grim an sootie, Clos’d under hatches, Spairges aboot the brunstane cootie, To scaud poor wretches!

Hear me, auld Hangie, for a wee, An let poor, damned bodies bee; I’m sure sma pleasure it can gie, Ev’n tae a deil, To skelp an scaud poor dogs like me, An hear us squeal!

11.5 The Scots language in the 19th and 20th centuries

Scotland has been described by academics as a ‘sociolinguist’s paradise’, meaning that the connections between language and social class are particularly interesting in this part of the world. We have seen how Scots was abandoned by the aristocracy and the upper classes, whose language became an echo of southern English.

At the same time, the ordinary people of Scotland continued to use their language in everyday situations, or for art or entertainment in poems, ballads and songs. It is unusual, though, to find Scots used in extended formal prose after the times of John Knox or James VI, so the following extract from the Scotchman Journal, published in Paisley around 1800, is particularly interesting.

Activity 9

Transcript

There’s a set o folk amang us, wham it costs sax times mair to maintain than a the meal-mongers, an shame haet they’re gude for, the maist o them: but meal-sellers we canna want. I mean the idle sloungers wha sell whisky an ither sorts o drink. Let ony body think on the swarms o lazy slinks wha leive by this trade in every neuk o the kintra, an he’ll easily see what an undeemous siller it costs to maintain them: for its no a wee thing that ser’s them: they maun hae the best for baith back an belly. Look juist at hame here, or gang in to Glasgow, or ony ither big toun, an at every ither door, ye’ll see ane o them staunin stechin wi his shouther at the door-cheek, settin out his red snout an muckle kyte. (Education Scotland, 2019 p.11).

Answer

This is a model answer. Your notes might be different.

- a.The writer here complains about the high price of meal, which meant that poor people found it very difficult to afford bread. However, most of the passage criticises sellers of alcohol, who are considered to be evil parasites, costing society dearly.

- b.Noteworthy Scots vocabulary here includes sax for six, neuk for corner, siller for silver/money, and kyte for belly. For us today, it may seem interesting or unusual to see such rich, broad Scots being used in formal, social/polemical writing like this.

At the same time as Scotland was moving swiftly forward into urban and industrial modernity during the 19th century, writers and scholars were also becoming increasingly interested in the past, and began to write down records of Scotland’s history and culture.

Romantic poets, composers and novelists were fascinated by the past. Some ‘antiquarian’ writers began to write down the Scots lyrics of the old country ballads, which had been sung for centuries, and in 1808, a pioneering linguist called John Jamieson published the first Scots dictionary – the Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language.

During the early part of the 20th century, writers and other intellectuals in Scotland were becoming aware of the Modernist movement in the arts. One aspect of modernist literature that appealed to many in Scotland, was the use of non-standard or specialised forms of language.

The confrontational poet Hugh MacDiarmid was the leader of the ‘Scottish Renaissance’ of the 1920s and 30s. MacDiarmid grew up in the late 19th century among Scots speakers in the border town of Langholm, and was a voracious reader and researcher. MacDiarmid invented what came to be known as ‘synthetic Scots’, a powerful hybrid of contemporary spoken Scots, peppered with colourful Scots words and idioms drawn from various periods of Scottish history.

MacDiarmid’s long Scots poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle is considered by many to be the greatest poem in Scottish Literature. These are the opening lines for you to listen to first of all.

Transcript

I amna’ fou’ sae muckle as tired – deid dune. It’s gey and hard wark coupin’ gless for gless Wi’ Cruivie and Gilsanquhar and the like, And I’m no’ juist as bauld as aince I wes.

The elbuck fankles in the coorse o’ time, The sheckle’s no sae souple, and the thrapple Grows deef and dour: nae langer up and doun Gleg as a squirrel speils the Adam’s apple.

And here is our translation of the opening lines for you to compare your understanding of the Scots version with:

I’m not drunk so much as tired – dead done.

It’s very hard work emptying glass for glass

With Cruivie and Gilsanquhar and people like them,

And I’m not quite as bold as I once was.

The elbow falters in the course of time,

The wrist isn’t as supple, and the throat

Becomes insensitive and dull: no longer up and down

Lively as a squirrel climbs the Adam’s apple.

This description is a metaphor for the generally unhappy and depressed state of Scotland during the nineteen twenties. The language here shows a range of interesting features, from the ‘…na’ negative ending on the verb amna to the familiar adverb gey, or the common adjective muckle. There is also some more unusual vocabulary like elbuck and sheckle for elbow and wrist. The word coupin, meaning ‘turning upside down’, is still commonly used.

Although MacDiarmid is renowned for using obscure older words, words from other languages, or scientific words, the Scots in these lines reads very much like real, rural Scots as it continues to be spoken in many areas today. Some have said that MacDiarmid politicised or even that he 'weaponised' the Scots language by aligning it with his nationalist politics. Many of the poets following in his wake continued to use Scots, and the language certainly flourished within Scottish literature in the 20th century.

![]()

A number of the writers who used Scots for literary purposes during the 20th century were Scottish Nationalists. However, in reality the Scots language is used by people at all points on the political spectrum. Consider whether you think the use of Scots by political writers like Hugh MacDiarmid is a good thing, because literary use promotes the language and keeps it alive. Or is the political use of Scots detrimental to the language, suggesting that it ‘belongs’ more to one political group than to others?

Poet and folklorist Hamish Henderson travelled the length and breadth of Scotland during the 1950s and 60s to record the voices and stories of ordinary Scots (and Gaelic) speakers. It was Henderson who wrote the Scots song Freedom Come All Ye, a song many have suggested would make a fitting reconciliatory and internationalist anthem for Scotland. The Scots lyrics of Henderson's song were sung by a South African performer at the opening of the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow.

Another significant moment in the history of Scots came in 1983, with the publication of W.L. Lorimer's magnificent translation, The New Testament in Scots. Lorimer was a scholar of Ancient Greek and a university lecturer. He had been brought up among Scots speakers in Perthshire, and dedicated much of his life to the Scots New Testament. The translation is quite remarkable in its range and richness. Lorimer translated directly from the original Hebrew into Scots, using different regional varieties of Scots to represent the different dialects of the original Gospels.

The rural provenance of so much of the Scots language means that it lends itself particularly well to the tales of farmers and fishermen that are found in the parables and gospels.

So, Scots was used in the 20th century for the cultural high purposes of poetry, national song, and translation of the Gospels. It continued to be used by millions of speakers, particularly throughout lowland Scotland, the Scottish cities, and the Northern Isles. It had survived the vicissitudes of the Reformation, the Union of the Crowns, the Union of the Parliaments, and four hundred years of southward cultural orientation among the Scottish upper and middle classes.

It therefore remained largely absent from Scottish radio and television during 20th century, and was only rarely used for formal written prose, making little more than tokenistic appearances in the mainstream press, often in rather reductive 'Scots word of the day' style articles.

Recent activity by the Scottish Government may eventually result in the language gaining some more of the middle ground between 'high culture' literary usage and the everyday speech of working class people - the two areas where Scots is at its most apparent today.

The promotion of Scots in schools, the pioneering use of Scots by a small number of contemporary news outlets, and the establishment of new Scottish television channels (with the potential to better represent Scottish linguistic reality) all bode well for the future of the Scots. The launch in 2015 of the Scottish Government's Scots Language Policy may yet prove to be a significant point in the fortunes of this language, which many regard as a uniquely tenacious, rich and colourful national treasure.

11.6 What I have learned

Activity 10

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- what the Scots language is, and why it is considered a language in its own right

- how Scots emerged as the official language of the state during the Middle Ages; the poetic and literary ‘high culture’ associated with the language during the Middle Ages

- the use of Scots during Renaissance and Reformation times

- the changing fortunes and status of Scots during the 17th and 18th centuries, including linguistic Anglicisation and the 18th century ‘Vernacular Revival’

- the perseverance of the Scots language during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Further research

You can browse or search the Statutes of the Scottish Parliament.

You can browse a facsimile of John Knox’s History of the Reformation.

National Improvement Hub provides a comprehensive history of the development of the Scots Language, including video and audio files of Scots from the Middle Ages to the present.

This link is to a review of the New Testament in Scots, and includes some interesting discussion on the status of Scots in the late 20th century.

You can listen to Lorraine Henderson from Deacon Blue performing a moving rendition of Hamish Henderson’s Freedom Come All Ye.

Now go on to Unit 12: Scots song.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Course image: Bruce Eunson

Giving flowers Image: GLady from Pixabay

White Lee Wind Farm image: Simmy's Photography, https://www.flickr.com/photos/29685744@N05/7435741756. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Argyll 2014 image: Jackie Proven, https://www.flickr.com/photos/11488846@N05/14569646170 This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Portrait of John Knox: Public Domain image digitised by Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru-The National Library of Wales

Statue of Robert Fergusson: Stefan Schäfer, Lich, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue_of_Robert_Fergusson.JPG. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Bust of Lamb-Hugh MacDiarmid: Neil Werninck. All rights assigned to JRW Stansfeld. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/39/Lamb-Hugh_MacDiarmid.jpg. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/