Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 10:23 PM

Unit 14: Scots and the history of Scotland

Introduction

In this unit you will learn about the relationship between the Scots language and the history of Scotland. An understanding of the past needs to include an awareness – though not necessarily a thorough knowledge – of the languages that people used in earlier times.

In Scotland, the main languages that have been used for the last 1,000 years include Gaelic, Scots, French, Latin and English. Many other languages have also been spoken by people living in Scotland throughout this period, including the present: for example, according to the 2011 census Scotland has about 54,000 speakers of Polish and 24,000 speakers of Urdu.

This unit is divided into six sections in which you will learn who used the Scots language and how Scots interacted with other languages during different historical periods. Historical events and stories associated with them often contain memorable Scots words and phrases. Some examples of these will be explored in this unit.

Important themes to take notes on throughout this unit:

- the status and use of Scots at different periods of history

- historical events which had an impact on the use of Scots

- narratives of historical events in which Scots is used in speech or in writing

- the use of Scots in oral history, fiction, legend and song.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

14. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: As in English phrase stane and lime, masonry, masoned stone. Generally, Scottish forms and usages of Eng. stone. Adj. stanie, stan(e)y etc.

Example sentence: “He’s gaun tae bigg a dyke wi aw thae stanes ower there.”

English translation: “He’s going to build a wall with all those stones over there.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

He’s gaun tae bigg a dyke wi aw thae stanes ower there.

Model

He’s gaun tae bigg a dyke wi aw thae stanes ower there.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Language Links

The Scots stane and the English ‘stone’ are cognates, which means that they come from a common ancestor, the Old English stān. Scots is a Germanic language, so it has many cognates with languages such as German, Dutch or Swedish. Stane is one of such words – notice the German equivalent ‘Stein’ and the Dutch ‘steen’.

Note that the word stane, like many other words in Scots and English, can be used as a noun, verb and in combination with other words e.g. stane-deif, drystane dyke, chuckie-stane etc. Stane can also refer to a mass of rock, to large boulders or smaller stones, pebbles and pieces of rubble. The picture shown, for example, is of the Dwarfie Stane, a megalithic chambered tomb carved out of a large block of sandstone on the island of Hoy in Orkney.

Related word:

Definition: A low wall made of stones, turf, etc., serving as an enclosure.

Example sentence: “Geen doon yun broo an ower the dyke.”

English translation: “Go down that hill and over the wall.”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

“Geen doon yun broo an ower the dyke.”

Model

“Geen doon yun broo an ower the dyke.”

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

14.1 The status and use of Scots from c.1100 to the present

During the 12th and 13th centuries, Scots (or ‘Inglis’ as it was then commonly known) expanded into areas of Scotland, which had previously been Gaelic-speaking. In this period, Scots became the most widely spoken language of the country, although Latin and French were also very important means of expression for those few people who could read and write – some churchmen, lawyers and merchants and some members of the royal court and nobility.

During this period and later, Latin was the main language of legal and academic discourse. University lectures were delivered exclusively in Latin until the early 1700s; also the Acts of Scotland’s Parliament were written in Latin until 1424, after which they were written in Scots for about 180 years.

Language Links

To give you an impression of one the first Acts written in Scots, you can see and listen here to an extract from an Act of 1457 ordering wapinschawingis (weapon-showings) to be held throughout the land and for men to practise use of weapons instead of playing games:

Item: it is decretyt and ordanyt that wapinschawingis be haldin be the lordis and baronys spirituale and temperale four tymis in the yere. And that the fut ball and the golf be utterly cryt doune and not usyt. And that the bowe merkis be maide at ilk paroch kirk a paire of buttis and schuting be usyt ilk Sunday.…

Transcript

Item: it is decretyt and ordanyt that wapinschawingis be haldin be the lordis and baronys spirituale and temperale four tymis in the yere. And that the fut ball and the golf be utterly cryt doune and not usyt. And that the bowe merkis be maide at ilk paroch kirk a paire of buttis and schuting be usyt ilk Sunday.…

How did you find reading and listening to this extract? Can you identify links with English here? You might have found reading the extract fairly straightforward and noticed that the spelling of some of the words is close to English, and so is the word order. When looking up words from the text, such as ordanyt, in the DSL, you will see that they mostly appear in the listing of results prior to 1700, meaning that these are words where there are not many examples of use post-1700 in Scots.

There was then a transition period, which meant that by the end of the 1600s the Acts of Parliament were written mostly in English – which was from then on the language of formal writing. These changes reflect the shifting fortunes of the different languages in relation to political, economic and social developments: for a period, Scots supplanted Latin as the language of power, but was itself in turn supplanted by English.

In literature, Scots flourished from the late 14th century – when John Barbour (c.1320–1395) wrote his epic poem about King Robert I, The Brus – through to the glories of the Renaissance period when the court of James IV patronised poets such as William Dunbar (c.1460–c.1520), who wrote in a rich, ornate and complex Scots.

Dunbar’s contemporary Gavin Douglas (c.1474–1522), Bishop of Dunkeld, made a magnificent Scots translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, the Eneados, the first translation of this text into any Germanic language. Slightly earlier, the Dunfermline schoolmaster Robert Henryson (c.1420–c.1490) had written his versions of Aesop’s Fables and other poems such as The Testament of Cresseid.

All these poets acknowledged the influence of the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer on their work, but Gavin Douglas renamed the language he used as Scottis rather than ‘Inglis’: the Eneados, he said, was ‘writtin in the langage of Scottis natioun’. This was a deliberate political distancing from the English of England, although the languages used either side of the Border had already become very distinct in terms of vocabulary, syntax and pronunciation.

Activity 4

In this activity, you will be working with an extract from Eneados (Douglas, G., 1839, Book 1, line 104ff). This extract is particularly interesting as it provides a strong statement by Douglas about his use of Scots, or Scottish, as the language of his poetry.

Part 1

First of all, listen to the extract and try to follow Douglas’ statement.

Transcript

And thus I mak my protestatioun;

Fyrst I protest, beaw schirris, be your leif,

Beis weill avisit my wark or yhe repreif,

Consider it warly, reid oftar than anys;

Weill at a blenk sle poetry nocht tayn is,

And yit forsuyth I set my bissy pane

As that I couth to mak it braid and plane,

Kepand na sudron bot our awyn langage,

And speikis as I lernyt quhen I was page.

Nor yit sa cleyn all sudron I refus,

Bot sum word I pronounce as nyghtbouris doys:

Lyke as in Latyn beyn Grew termys sum,

So me behufyt qhilum or than be dum

Sum bastard Latyn, French or Inglys oys

Quhar scant was Scottis - I had nane other choys.

By the 17th century, Scots was undergoing Anglicisation under the influence of its powerful southern neighbour, and English was becoming the more dominant of the two languages (see the next section for reasons why this happened). The vast majority of the population still spoke Scots – outwith the Gaelic-speaking Highlands and Islands (Gaelic was spoken as far south as parts of Perthshire, Stirlingshire and southern Argyll until the late 18th century).

In the 18th century, there was a reaction against the dominance of English among some poets and songwriters, who often turned to Scots to express themselves. The best-known figures of this ‘Vernacular Revival’ are Allan Ramsay (1684–1758), Robert Fergusson (1750–74), and Robert Burns (1759–96).

After the Union with England of 1707, Scotland retained its own legal system, and Scots continued to be regularly spoken in the law courts by advocates and judges, as well as by some witnesses, as late as the first decades of the 19th century, even though all written and printed documents had long been produced only in English. In 1794, Robert MacQueen, Lord Braxfield (1722–99), said of Francis Jeffrey, who was newly an advocate in Edinburgh after having attended Oxford University: ‘The laddie has clear tint [lost] his Scotch and fund nae English’. This comment suggests that it was normal for Scots to be used by lawyers during this period. (Source: Rogers, P. (n.d.), Boswell and the Scotticism.

In the last 200 years or so, the division between English as the language of education and all formal usage including in the media, and Scots as the daily oral language of many Scottish people, has become firmly established. In the same period, English became a powerful global language, putting more pressure on Scots speakers to modify or abandon their Scots speech in most formal settings. However, as you will learn in the next section, this process has been going on for a much longer time.

14.2 Historical events with an impact on Scots

In this part, you will learn about some key events which affected the use, status and development of Scots.

In 1513, the Scots suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of an English army at the Battle of Flodden, which saw the death of King James IV and many of the Scottish nobility. A long period of instability followed during the minority rule of James V, the patronage of poets at the royal court was not sustained, and the richest period of literary writing in Scots came to an end.

In 1542, James V died and was succeeded by his infant daughter Mary. In the first months of her reign, in March 1543, an Act of Parliament was passed authorising the use of a vernacular Bible (that is, one not in Latin).

Listen to the Act read by Jeremy Smith.

Transcript

It is statute and ordanit that it salbe lefull to all oure sovirane ladyis lieges to haif the haly write, baith the New Testament and the Auld, in the vulgar toung, in Inglis or Scottis, of ane gude and trew translatioune and that thai sall incur na crimes for the hefing or reding of the samin.

It is interesting that no preference was made between ‘Inglis’ and ‘Scottis’ as to which ‘vulgar toung’ should be used. This Act predates by eighteen years the Reformation of 1560 led by John Knox. It was largely because of the close links between Knox and other Reformers and England, and the ready availability of copies printed in English, that by the end of the century it had become normal to read and hear from the Bible in that language, not in Scots. Some partial Scots translations were made but they were not published.

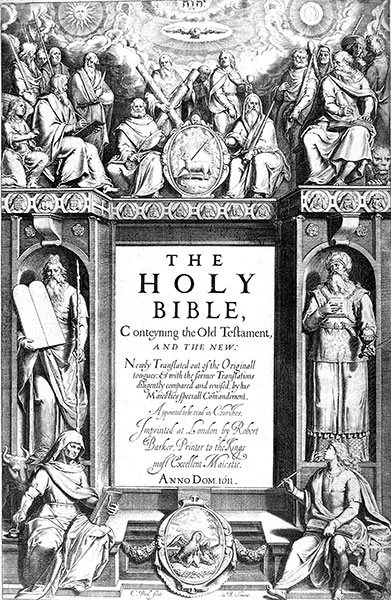

With the Union of the Crowns in 1603, James VI left Scotland and ruled his kingdoms from London. In 1611, a new translation of the Bible, authorised by James, was published. We know this as the Authorised Version or King James Bible, and it became universally used throughout the British Isles. Historically, this Bible has had more influence on the cultural life of Scotland than any other book.

The fact that it was written in English was a major factor in strengthening the position of English as the language of formal writing and discourse in all walks of life, not just religion. Arguably, it also helped to create a perceived ‘superior’ status of English over Scots.

Activity 5

James VI was himself a poet and gathered a group of other poets around him at his court in Edinburgh, known as the Castalian Band. An important effect of the removal of the court to London was that royal patronage of the arts, and literature in particular, was abruptly curtailed in Scotland. Even before James’s departure, however, it is possible to see a shift in language priorities happening in Scotland.

Compare the following two extracts from James’s prose work on statecraft, Basilicon Doron (Greek for ‘royal gift’). The first extract comes from the manuscript of the book, written in Scots in 1598, and the second from the edition published in 1603 by Robert Waldegrave, the King’s official printer, in Edinburgh.

The closer political and economic ties between Scotland and England, especially after the Union of Parliaments of 1707, meant that the language of the larger, stronger nation became the standard, official language of both.

But it is important to note that this divergence between ‘formal’ and written English and ‘informal’ and spoken Scots was already happening before the Union: the close relationship between the languages undoubtedly facilitated this process, as many Scots speakers were well able to read, write and speak English when they needed to do so.

During the 18th century scientific and philosophical movement we now call the Scottish Enlightenment, it suited writers such as David Hume and Adam Smith to write their books in English, and to learn how to eradicate what were called ‘Scotticisms’ from their prose, even though they continued to speak Scots in their daily lives. The market for their ideas was clearly much greater if they wrote in English.

Yet, this same period was precisely when the ‘Vernacular Revival’ of poetry and song composed in Scots, mentioned in section 2 of this unit, was taking place. This suggests that the intellectual and commercial attractions of English were balanced by an equally strong need to express some feelings.

14.3 Scots language in narratives of historical events

In this section, you will find examples of the appearance of Scots in records of historical events.

In records of historical events, sometimes Scots phrases and sentences are recorded as what individuals are supposed to have said: as such they are part of ‘what happened’, but they are embedded within narratives written in English. Elsewhere, entire narratives are written in Scots. You may want to make notes about these different examples of Scots in prose-writing, focusing on, for example, the relationship between Scots as ‘dialogue’ and English as ‘narrative’. This relationship will also feature in the next section of this unit.

Below you will engage with a list of examples, where one Scots word in particular is extracted. These examples highlight how Scots language was used in context at the time, i.e. as the language of dialogue in an English language narrative. We have worked through the first example for you so that you can see what you should do in the following activity. The extracted word is sicker, used in dialogue, and in the engagement with the DSL we were looking for instances of the use of the word in citations that refer to or retell historical incidents.

Example 1

Word to search in the DSL: Sicker

The meeting of John Comyn and Robert the Bruce in the church of the Greyfriars, Dumfries, 10th February 1306, as recorded by Sir Walter Scott.

These two haughty barons came to high and abusive words, until at length Bruce… struck Comyn a blow with his dagger. Having done this rash deed, he instantly ran out of the church and called for his horse. Two gentlemen of the country, Lindesay and Kirkpatrick, friends of Bruce, were then in attendance on him. Seeing him pale, bloody, and in much agitation, they eagerly inquired what was the matter.

‘I doubt,’ said Bruce, ‘that I have slain the Red Comyn.’

‘Do you leave such a matter in doubt?’ said Kirkpatrick. ‘I will make sicker!” – that is, I will make certain.

Accordingly, he and his companion Lindesay rushed into the church, and made the matter certain with a vengeance, by dispatching the wounded Comyn with their daggers.

DSL mentions of Sicker in connection with historical events

1. meaning: safe, secure, free from danger:

s.Sc. 1897 E. Hamilton – Outlaws iii.: There's nae man in Liddesdale can sickerly lead a party at night thro' the Foulbogshiel.

5. meaning: of things: certain, sure

Sc. c.1715 W. Macfarlane – Genealogical Collections (S.H.S.) II. 337: This Charter is Dated at Air 15 December 1425 And for the Mare Sickerness the Seals of these Noble and Mighty Lords with Instance have procured to be hanging to their present Letters.

7. meaning: of people: prudent, cautious

Ayr. 1822 J. Galt – The Provost xliii.:

Mr. Peevie, one of the very sickerest of all the former sederunts, came to me next morning.

8. meaning: not open to doubt

Sc. 1824 G. Chalmers – Caledonia III. 79: Roger Kirkpatrick, who despatched John Cumin after Robert de Brus had given him “a perilous gash;” and from this deed took as his motto, “I'll mak sicker.”

Language Links

The adverb sicker used by Kirkpatrick in the extract above is an example of the close relationships between the Scots, English, German and Dutch languages. Looking up the meaning of today’s German adjective and adverb (can also be used as a verb) sicher will highlight that this adjective carries the same nuances of meaning as outlined in the DSL entry for sicker.

The Scots word has common roots with Dutch, where people in the Middle Ages used sēker, and today say zeker. The north of the Netherlands is a region where people speak Frisian, and in Old Frisian people used siker with the same meaning. Old English used to have a very similar word: sicor, which has now become secure, which carries an aspect of the meaning of the Old English word.

Activity 6

Now work with more extracts in the same way as we have shown you above.

- a.First of all, listen to each extract in the examples 2 to 5. Try to listen without reading the transcript and work out what the extract reports.

- b.Then, read the extract and compare your understanding of it with what you understood listening to the extract.

- c.Finally, go to the online Dictionary of the Scots Language, enter that word in the ‘search’ box and explore the main definition, sub-definitions and citations that appear. Make notes of those citations which refer to historical incidents as you have seen in our example above.

Example 2

Extract from Bellenden’s Croniklis of Scotland (1536) reporting the murder of James I at Perth, 20th February 1437.

Transcript

Ane servant, namit Walter Straitoun, opnit the dure, and went furth to ressave wine to the Kingis collation. Als sone as he saw thaim aufully arrayit at the dure, he cryit ‘Treason!’ and maid him, with all his strenth, to return agane; nochtheles, he was sone slane. Yit, the slaing of him maid sic tary to the laif, that ane young madin, namit Katherine Douglas, quhilk was efter maryit on Alexander Lovell of Bolunny, stekit the dure: and, becaus the bar was away that suld have closit the dure, scho schot hir arme into the place quhare the bar suld have passit. Scho was bot young, and hir bonis not solide, and thairfore, hir arme was sone brokin all in schonder, and the dure doung up, be force. Incontinent, thay enterit: and, efter that thay had slane the familiar servandis that maid debait for the time, they slew the King, with mony cruell woundis, and hurt the Quene, in his defence.

Word to search in the DSL: Steek

Ane servant, namit Walter Straitoun, opnit the dure, and went furth to ressave wine to the Kingis collation. Als sone as he saw thaim aufully arrayit at the dure, he cryit ‘Treason!’ and maid him, with all his strenth, to return agane; nochtheles, he was sone slane. Yit, the slaing of him maid sic tary to the laif, that ane young madin, namit Katherine Douglas, quhilk was efter maryit on Alexander Lovell of Bolunny, stekit the dure: and, becaus the bar was away that suld have closit the dure, scho schot hir arme into the place quhare the bar suld have passit. Scho was bot young, and hir bonis not solide, and thairfore, hir arme was sone brokin all in schonder, and the dure doung up, be force. Incontinent, thay enterit: and, efter that thay had slane the familiar servandis that maid debait for the time, they slew the King, with mony cruell woundis, and hurt the Quene, in his defence.

Example 3

Extract from Pitscottie’s Historie and Cronicles of Scotland (1782) detailing the birth of Mary, future Queen of Scots, at Linlithgow, 8th December, and the death of her father James V at Falkland, 14th December, 1542

Transcript

Be this the post came out of Lythtgow schawing to the king goode tydingis that the queen was deliuerit. The king inquyrit ‘wither it was man or woman’. The messenger said ‘it was ane fair douchter’. The king ansuerit and said: ‘Adew, fair weill, it come witht ane lase, it will pase witht ane lase’. And so he recommendit himself to the Marcie of Almightie God and spak ane lyttill then frome that tyme fourtht, bot turnit his bak into his lordis and his face into the wall.’

Word to search in the DSL: Lass

Be this the post came out of Lythtgow schawing to the king goode tydingis that the queen was deliuerit. The king inquyrit ‘wither it was man or woman’. The messenger said ‘it was ane fair douchter’. The king ansuerit and said: ‘Adew, fair weill, it come witht ane lase, it will pase witht ane lase’. And so he recommendit himself to the Marcie of Almightie God and spak ane lyttill then frome that tyme fourtht, bot turnit his bak into his lordis and his face into the wall.’

Note: ‘It cam wi a lass, it’ll pass wi a lass’ (the modern form of the phrase ‘it come witht ane lase, it will pase witht ane lase’) is believed to be a reference to the Stewart claim to the throne inherited from Marjorie, daughter of Robert the Bruce, whose marriage in 1314 to Walter, High Steward of Scotland, established the royal Stewart line.

Example 4

This is an extract that illustrates the elderly John Knox’s preaching style at St Andrews, c.1570, as detailed in the Diary of James Melville.

Transcript

In the opening upe of his text he was moderat the space of an half houre; bot when he enterit to application, he maid me sa to grew and tremble, that I could nocht hald a pen to wryt… Mr Knox wald sum tyme com in and repose him in our colleage yeard, and call us schollars unto him, and bless us, and exhort us to knaw God and his wark in our contrey, and stand be the guid causes, to use our tyme weill, and lern the guid instructione, and follow the guid exemple of our maisters… I saw him everie day of his doctrine go hulie and fear, with a furring of martriks about his neck, a staff in the ane hand, and guid godly Richart Ballanden his servand haldin upe the uther oxter, from the Abbaye to the paroche Kirk, and be the said Richart and another servand lifted upe to the pulpit, whar he behovit to lean at his first entrie, bot, or he had done with his sermon, he was sa active and vigorus, that he was lyk to ding that pulpit in blads and flie out of it.’

Word to search in the DSL: Oxter

In the opening upe of his text he was moderat the space of an half houre; bot when he enterit to application, he maid me sa to grew and tremble, that I could nocht hald a pen to wryt… Mr Knox wald sum tyme com in and repose him in our colleage yeard, and call us schollars unto him, and bless us, and exhort us to knaw God and his wark in our contrey, and stand be the guid causes, to use our tyme weill, and lern the guid instructione, and follow the guid exemple of our maisters… I saw him everie day of his doctrine go hulie and fear, with a furring of martriks about his neck, a staff in the ane hand, and guid godly Richart Ballanden his servand haldin upe the uther oxter, from the Abbaye to the paroche Kirk, and be the said Richart and another servand lifted upe to the pulpit, whar he behovit to lean at his first entrie, bot, or he had done with his sermon, he was sa active and vigorus, that he was lyk to ding that pulpit in blads and flie out of it.’

Vocabulary help

- grew: grue

- hulie and fear: warily

- furring of martriks: pine marten fur

- or he had done: before he was finished

- ding in blads: smash to bits

Example 5

This extract from James Pagan’s Sketch of the History of Glasgow (1847) reports the execution of royalist prisoners in Glasgow, 28th and 29th October 1645, following the Battle of Philliphaugh.

Transcript

That the spectacle was an agreeable one to a large number of the citizens, there is no reason to doubt; Mr David Dickson, professor of divinity in Glasgow college, was particularly elated at the smiting of the royalists, and exclaimed, ‘The wark gangs bonnily on,’ a saying which passed into a proverb, and is used significantly in Glasgow to the present day.’

Word to search in the DSL: Wark

That the spectacle was an agreeable one to a large number of the citizens, there is no reason to doubt; Mr David Dickson, professor of divinity in Glasgow college, was particularly elated at the smiting of the royalists, and exclaimed, ‘The wark gangs bonnily on,’ a saying which passed into a proverb, and is used significantly in Glasgow to the present day.’

Example 6

Jenny Geddes and the riot at St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, 23rd July 1637, caused by the first attempt to use the Anglican Book of Liturgy during service.

King Charles I, who had come to Scotland in 1633, was keen to introduce Anglican-style church services across Scotland and had arranged a Commission to draw up an Anglican prayer book suitable for Scotland. These developments were met with widespread opposition as Scotland had its Episcopal Church, which was related to the Anglican Church but much more puritan in doctrine and practice.

In 1637, an Edinburgh printer had produced such an Anglican prayer book and it was tried out at St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, on 23rd July 1637 for the first time, which led to the events recounted in the two extracts below.

The first (a) is taken from Thomas Carlyle’s commentary in his edition of Oliver Cromwell’s letters and speeches. It contains the words reputedly used by Jenny Geddes, an Edinburgh vegetable-stall keeper. Although there is no firm proof that she actually existed, she is one of the most famous figures in Scottish popular history. Carlyle’s version of events is written from a 19th-century perspective.

The second extract (b), ‘The Stonyfeild Saboth Day’, is a contemporary account of the same event which exists in a manuscript in the Advocates’ Library in Edinburgh.

(a)

‘Let us read the Collect of the Day,’ said the Pretended-Bishop from amid his tippets; – ‘De’il colic the wame of thee!’ answered Jenny, hurling her stool at his head. ‘Thou foul thief, wilt thou say mass at my lug?’ I thought we had got done with the mass some time ago; – and here it is again! ‘A Pape, a Pape!’ cried others: ‘Stane him!’ - In fact the service could not go on at all. This passed in St Giles’s Kirk, Edinburgh, on Sunday 23rd July, 1637.

(b)

No les worthie of observatioun is that renouned Cristian valyancie [valour] of ane other godly woman at this same seasone: for when scho hard a young man behind hir sounding furth amen to that new composed church comedie (God’s service or worschippe it deserves not to be called) which then wes impudentlie acted in publict sicht of the congregatioun, scho quicklie turnd hir about and efter scho haid warmed both his cheikis with the weght of hir handis, scho thus schott against him the thunderbolt of hir zeale ‘Fals theiff (said scho) is thair no other pairt of the churche to sing mess in but thow most sing it at my lug?’ The young man being dasched at such a suddant rencounter, gave place to silence.

Activity 7

Before you move on to the final part of this unit, you may wish to consider some questions about the material you have read and researched so far.

What are the differences between Scots and English in the texts you have looked at in this section?

Can you find examples, in any of the six texts in section 3, of differences which are mainly determined by:

- spelling?

- pronunciation?

- vocabulary?

Are there other differences, which are not simply linguistic?

Is it possible to identify ‘attitude’ or ‘mood’ as features of Scots or English?

What is the effect on the reader or listener of Scots words and phrases being contained within predominantly English texts? Why do you think does this not happen the other way around, i.e. English words and phrases being contained within predominantly Scots texts?

14.4 Scots in oral history

In this section and the next, you will learn about Scots language being used in informal kinds of historical narrative, namely oral history, fiction, legend and song. It is worth noting that some of the key documents in Scottish history, such as the Declaration of Arbroath (1320), the National Covenant (1638) and the Treaty of Union (1707) were written in Latin or English, not in Scots.

Is this a further example of what was described in section 2 of this unit, i.e. ‘the shifting fortunes of the different languages in relation to political, economic and social developments: for a period, Scots supplanted Latin as the language of power, but was itself in turn supplanted by English’. And this in part explains the comparatively much stronger presence of Scots in non-formal kinds of historical narrative, such as those you will find discussed below.

Oral history

Oral history is the recording of people’s memories, experiences and opinions. It is a way of expanding historical knowledge and evidence that includes the voices and experiences of people, such as women and people from working-class or ethnic communities, who have often been hidden or excluded from mainstream or academic history.

Activity 8

Listen to a recording, made in 1962, of Jock MacShannon, from Campbeltown talking about his working life. He had many different jobs during his working life, including being a coalminer, distillery worker and stoker on board a coaster.

Make notes while listening to Jock remembering these events. Then decide which of the statements below are true or false according to Jock’s report.

a.

False

b.

True

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

False

b.

True

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

a.

False

b.

True

The correct answer is a.

a.

True

b.

False

The correct answer is a.

Working in Campbeltown between 1918 and 1945

Between 1918 and 1945, there had been the Great Depression of the 1930s during which many workers, along with their families, suffered great hardship because of unemployment. Miners were no exception. By the end of the Second World War working conditions had improved and mineworkers’ trade unions were in a stronger position to negotiate better terms for their members. Furthermore, the post-1945 Labour Government nationalised the mining industry, providing much greater stability of employment.

At least four factors contributed to the closure of distilleries in Campbeltown in the 1920s. The First World War had an immediate effect on demand and also saw the introduction of the Immature Spirits Act in 1915, which required whisky to be bonded for a minimum of two years, extended to three years in 1916.

These two factors affected all distilleries, but Campbeltown was particularly hard-hit by the introduction of Prohibition in the USA in 1920: Campbeltown’s location and harbour was the most convenient place from which to transport whisky casks to North America, but this advantage was lost during the years (until 1933) of Prohibition. Lastly, the local coal seam was exhausted and the pit closed in 1923, which added greatly to distillery fuel costs.

14.5 Scots in fiction, legend and song

Fiction

Some people acquire their knowledge of history not through history books but through historical novels. It is sometimes said that Scotland was the birthplace of the historical novel owing to the success of Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley Novels, written between 1814 and 1832. Since Scott’s time, many Scottish writers, such as James Hogg, John Galt, Robert Louis Stevenson, Neil Munro, John Buchan, Nigel Tranter and Dorothy Dunnett, have written novels set in the Scottish past, and many of them have used Scots, mainly in dialogue, to capture the atmosphere and events of the past.

In the following extract, taken from The Heart of Midlothian (1818) by Sir Walter Scott, the true event depicted took place in 1736. An officer of the City Guard, Captain John Porteous, was found guilty of ordering his soldiers to open fire on a crowd of citizens at a public hanging, and was himself sentenced to be hanged. However, at the last minute he was granted a reprieve by the Government. Many Scots saw this as unwanted interference in Scottish affairs by London. Scott uses the conversation of his fictional characters, disappointed not to have seen Porteous hang, to illustrate anti-Union discontent:

‘An unco thing this, Mrs Howden,’ said old Peter Plumdammas to his neighbour the rouping-wife, or saleswoman, as he offered her his arm to assist her in the toilsome ascent, ‘to see the grit folk at Lunnon set their face against law and gospel, and let loose sic a reprobate as Porteous upon a peacable town!’

‘And to think o’ the weary walk they hae gien us,’ answered Mrs Howden with a groan; ‘and sic a comfortable window as I had gotten, too, just within a penny-stane-cast of the scaffold – I could hae heard every word the minister said – and to pay twal pennies for my stand, and a’ for naething!’

‘I am judging,’ said Mr Plumdamas, ‘that this reprieve wadna stand gude in the auld Scots law, when the kingdom was a kingdom.’

‘I dinna ken muckle about the law,’ answered Mrs Howden; ‘but I ken, when we had a king, and a chancellor, and Parliament-men o’ our ain, we could aye peeble them wi’ stanes when they werena gude bairns – But naebody’s nails can reach the length o’ Lunnon.’

‘Weary on Lunnon, and a’ that e’er came out o’t!’ said Miss Grizel Damahoy, an ancient seamstress; ‘they hae taen awa our Parliament, and they hae oppressed our trade. Our gentles will hardly allow that a Scots needle can sew ruffles on a sark, or lace on an owerlay.’

In this passage, Scott cleverly outlines some of the grievances, both serious and petty, that many Scots felt in the decades immediately following the loss of national independence in 1707. Partly through humour and especially through a striking and lively use of Scots, he makes some serious points. The second speech of Mrs Howden, beginning ‘I dinna ken muckle about the law’, is now one of the quotations engraved on the outside wall of the Scottish Parliament building. Read it carefully and make a short analysis of what political point Scott is making through his fictional character.

Legend

You may already think that some of the historical events discussed in this section have a more ‘legendary’ than ‘factual’ feel to them. For example, the ‘mak sicker’ story (the murder of Comyn by Bruce), or the story of Jenny Geddes’s remarks are not supported by strong historical evidence, even though the events they are a part of undoubtedly took place. This is where history and popular legend become confused. Sometimes the legend is so much more powerful than what the historical record shows that it becomes almost impossible to challenge.

A good example of this is the phrase ‘Whaur’s yer Wullie Shakespeare noo?’ allegedly shouted by a member of the audience at the first performance of John Home’s play Douglas in Edinburgh in 1756. It is not clear whether the cry was deeply ironic or was made by an enthusiastic Scottish patriot, or if it was made at all.

![]()

Look up the word Whar in the Dictionary of the Scottish Language here and read the items specifically related to this phrase: ‘Whaur’s yer Wullie Shakespeare noo?’

- What does this tell you about the ability of a good story to generate further manifestations of itself?

- Do you think the legend, and others like it, would have been perpetuated if the sentence had been delivered in English rather than Scots?

Song

As you have studied in unit 12, many incidents in Scottish history have been celebrated or marked by songs written and performed in Scots. There are countless examples of this: battles, feuds, emigration, land clearance, crime, work of various kinds have all had songs in Scots written about them.

To take the theme of battles, ‘Scots Wha Hae’ by Robert Burns (1793) is about the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314; ‘The Flooers o’ the Forest’ by Jean Elliot (1756 or 1758) is a lament for the Battle of Flodden in 1513; ‘Hey Johnnie Cope’ by Adam Skirving records the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745; and Hamish Henderson’s ‘The 51st Highland Division’s Farewell to Sicily’ records part of the Italian campaign of the Second World War.

![]()

The words of Hamish Henderson’s song can be read at the Scottish Poetry Library’s website.

- What do these words tell you about the Italian campaign? With whom do the songwriter’s sympathies lie?

- Does the use of Scots give you any indication about the answers to these questions?

You may wish to think of a historical theme other than war, and research three or four songs written in Scots that illustrate that theme. Again, make notes about how the use of Scots helps to illuminate history or to memorialise historical events.

- Does the fact that the narration takes the form of a song sung in Scots help to make the story more memorable? If so, why?

14.6 What I have learned

Activity 9

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- the status and use of Scots at different periods of history

- historical events which had an impact on the use of Scots

- narratives of historical events in which Scots is used in speech or in writing

- the use of Scots in oral history, fiction, legend and song.

Further research

Billy Kay’s Scots: The Mither Tongue, 2006, Edinburgh, Mainstream Publishing, pp. 55-86 provides more interesting insights into the importance and use of Scots language in relation to Scotland’s history.

Read this title to learn more about the interrelation between Scots language and history of Scotland: Yeoman, L. (2000) Reportage Scotland: History in the Making, Edinburgh, Luath Press.

The Tobar an Dualchais / Kist o Riches website contains over 38,000 oral recordings made in Scotland and further afield, from the 1930s onwards. The items you can listen to include stories, songs, music, poetry and factual information. The website can be searched using various filters, including a Scots language filter.

Now go on to Unit 15: Scots and religion.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Photo of stane: Grovel at English Wikipedia - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dwarfie_Stane,_Island_of_Hoy,_Orkney.jpg. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Photo of dyke: Walter Baxter - https://www.geograph.org.uk/reuse.php?id=1387241 - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Statue of Gavin Douglas, Bishop of Dunkeld: Kim Traynor - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue_of_Gavin_Douglas,_Bishop_of_Dunkeld.JPG This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Photograph of The Flodden memorial: Stephen McKay - https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/39370 This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Painting of Mary Queen of Scots: The Artchives/Alamy Stock Photo

King James Bible: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

Declaration of Arbroath: National Records of Scotland - https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/features/the-declaration-of-arbroath - Reproduced under the terms of the OGL, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence

Scottish Parliament photograph: Mary and Angus Hogg - https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/5329899 - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/