Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 3:03 AM

Unit 15: Scots and religion

Introduction

Language plays an important role in religion through sacred texts or scriptures, like the Jewish Tanakh, the Muslim Koran, and the Christian Bible. But the forms of words used in services of worship, which are sometimes called liturgies, are also important. These might include regular occasions, but also festivals such as Easter and Christmas, or rites of passage such as births, marriages and deaths.

When the Christian religion spread into Scotland, from the 5th century, the language it used was Latin, the official language of the Roman Empire. The liturgies used, notably for the Mass, were in Latin, and the Bible was read in Latin from a version known as the Vulgate. This continued until the Reform movements of the 16th century.

These texts were recorded and handed on for centuries in carefully copied manuscripts until the invention of printing. Most people understood what was happening through the actions of the priests, and the paintings and stained glass that adorned the churches. The actual words were more respected than understood.

In this unit, you will be able to work with some passages from the most influential 16th century Bible translations and other extracts from famous religious texts and texts that have religious contexts. As well as that, this unit provides many opportunities for you to practice listening to the Scots language, most of all older Scots, and you will be able to speak some Scots again, too.

Important themes to take notes on throughout this unit:

- how Protestant reformers translated the Bible into commonly spoken or vernacular languages

- the Bassendyne Bible of 1579 – the first non-Latin Bible to be printed in Scotland

- the impact of The Book of Common Order not being in Scots

- the effects of Anglicisation

- the Gude and Golie Ballatis

- the publication in 1901 of the New Testament in Braid Scots,which attempted to imitate the language of Burns rather than the medieval poets

- Lorimer’s translation of the New Testament from Greek into Scots.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

15. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: church in all senses.

Example sentence: “The weddin wis at twal o clock, aabody hed ta be in the kirk fir quarter tae.”

English translation: “The wedding was at twelve o’ clock, everybody had to be in the church for a quarter to.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

The weddin wis at twal o clock, aabody hed ta be in the kirk fir quarter tae.

Model

The weddin wis at twal o clock, aabody hed ta be in the kirk fir quarter tae.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Language Links

One word which many people tend to use as an obvious example of the close links between the Scots and the German languages is the noun kirk, in German die Kirche. Both have exactly the same meaning and have hardly changed over centuries. In Older Scots the noun kirk was first recorded around 1160; from around 1420 we find records of the noun spelled as kyrkyn which is even closer to the German Kirche or plural Kirchen.

As in the Scots language, the noun in German is used to describe two things: a representative church building where Christian people worship, which can be built in ornate or simpler styles and usually has at least one bell tower; or a congregation of Christians, the institution of the church. The Scots and German nouns stem from the Old Greek noun kȳrikón (κυρικόν) ‘house of god’, which was first recorded in the 4th century.

Related word:

Definition: a book

Example sentence: “As the Guid Buik says, luve God abuve al an yi nychtbour as yersel.”

English translation: “As The Bible says, love God above all and your neighbour as yourself.”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

As the Guid Buik says, luve God abuve al an yi nychtbour as yersel

Model

As the Guid Buik says, luve God abuve al an yi nychtbour as yersel

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

15.1 Scots language variations in 16th century Bible translations

In the 16th century, Roman Catholic and Protestant reform movements emphasised the need for more understanding, and more personal styles of devotion. Literacy was spreading especially in the towns and the greater availability of books encouraged more reading and more translation of texts. Scholars studied the Christian Bible in Greek and Hebrew, stimulating new interpretations.

Above all, Protestant reformers such as Martin Luther and William Tyndall translated the Bible into commonly spoken or vernacular languages such as German and English. Their aim was to challenge the authority of the Roman Catholic Church and its interpretation of Christianity’s sacred texts.

In the 16th century, the most commonly spoken languages in Scotland were Scots and Gaelic. Scots was dominant in urban areas and was the language chosen when the Roman Catholic authorities tried to encourage a greater knowledge of religious teaching across the population. The example sentence in the handsel was one of seventy texts or sayings that the influential John Hamilton, archbishop of St Andrews wanted people to memorise, through his Hamilton’s Catechism printed in St Andrews in 1551:

AS THE GUID BUIK SAYS, LUVE GOD ABUVE AL AN YI NYCHTBOUR AS YERSEL.

This is, in Scots, what Christ says in the New Testament when he is asked what is the most important thing in the Jewish Law or Torah. His words, in the familiar English of the Authorised Version are, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength, and your neighbour as yourself’. The Scots version above is compressed, pithy and to the point.

Activity 4

In this activity, you compare three different translations of Christ’s words cited above. Note your comments on the literal vs the literary translation and why you think the notable differences arise.

a. [Scots of 1555]

As the Guid Buik says, luve God abuve al an yi nychtbour as yersel

b. [English Authorised version]

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and strength, and your neighbour as yourself.

c. [Word-for-word translation of Scots in English]

As the good book says, love God above all and your neighbour as yourself.

* Note in the word-for-word version it is “the good book” instead of “The Bible” as used in the example sentence above as well as the handsel.

Answer

This is a model answer, your notes might be different.

As the text says, the Scots version is compressed and yes, it is quite to the point. There is an element of poetry to the English Authorised Version – but yes, it does use quite a few more words to say the same thing. Having said that, the word-for-word Scots translation does seem to lack emphasis which the English contains when going into detail such as “all your heart and soul and strength” instead of just “abuve al” like in the Scots version from 1555.

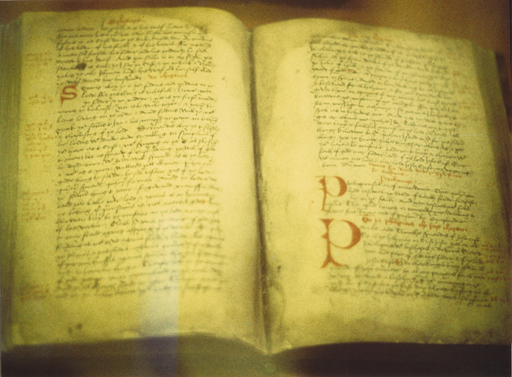

Scottish Protestants were keen to see the whole of the Christian Bible available in Scots. A radical Ayrshire reformer, Murdoch Nisbet worked in secret to translate the New and parts of the Old Testament, working from the Latin Vulgate and an English ‘underground’ version originally created by the Lollards, the 14th century dissenters, inspired by John Wycliffe.

Murdoch Nisbet’s translation of the New Testament into Scots was the first ever undertaken. [… His] New Testament is a wonderful source of information on what the differences between English and Scots at that period were thought to be. A striking feature of the Scots translation is that to the modern eye it is actually rather more accessible than the English.

Nisbet hid his work in a cellar beneath his house where he also held illegal religious gatherings, or conventicles, at which he read aloud from his translation. His labour continued for decades – beginning perhaps in Europe – until his death in 1559. However, Nisbet’s New Testament received no official recognition and was only published as a historical source text in 1901–05.

Why did this happen? The Protestant Reformers wanted to transfer the focus of religious inspiration and authority from the Church to the Bible. The written and printed Buik was to become the mainstay and guide. But the newly translated Bible came from Geneva, where John Calvin had established a Reformed city state, and where John Knox lived in exile between 1556 and 1559. More specifically, Knox was a minister in Geneva to the English-speaking congregation which was composed of prominent Protestants who had fled the rule of the Roman Catholic Mary Tudor in England.

The learned among them set about creating the Geneva Bible, an updated version of William Tyndale’s English translation published in 1526, and Knox provided the explanatory or interpretative notes for this definitive Protestant version. When Knox returned to Scotland in 1559, he brought with him the Bible and the Protestant orders of service, which had become established in Geneva. These then became the Scottish norm.

Here is the passage in Murdoch Nisbet’s Scots translation that parallels Archbishop Hamilton’s Catechism, containing the text inscribed on John Knox House:

And ane of them, a techer of the law, askit Jesu, tempand him, Maistre, whilk is a gret comendment in the law? Jesus said to him, Thou sal lufe thi Lord God of al thi hart, and in al this saule, and in al thi mynde. This is the first and the gretest commandment. And the second is like to this, Thou sal luf thi nechbour as thir self.

You can now listen to this passage being read out to further develop your understanding of older spoken Scots.

Transcript

And ane of them, a techer of the law, askit Jesu, tempand him, Maistre, whilk is a gret comendment in the law? Jesus said to him, Thou sal lufe thi Lord God of al thi hart, and in al this saule, and in al thi mynde. This is the first and the gretest commandment. And the second is like to this, Thou sal luf thi nechbour as thir self.

This passage from Nisbet’s text is an example of the fact that Scots was used in both written and spoken forms in the 16th century, and had commonly applied standards, despite variations in spelling – just like the situation we have today.

There is a further famous passage in Murdoch Nisbet’s Scots translation, that describes what came to be known as the ‘Last Supper’, a final meal shared between Jesus and his disciples. This event became the basis of the most important Christian service and liturgy, in both Roman Catholic and Protestant traditions.

Activity 5

In this activity you will compare the passages about the ‘Last Supper’ from Nisbet’s version in Scots with that of the Bassendyne Bible of 1579, the first non-Latin Bible to be printed in Scotland, which was a direct reprint of the second edition of the Geneva Bible published first in 1560.

Listen to both passages first of all and take some notes to answer the following questions.

- What are the differences and commonalities in the two passages?

- Did you find it difficult to follow the spoken Scots?

- Which passage is more ‘to the point’?

a. The ‘Last Supper’ passage from Nisbet’s version

Transcript

And quhen they soupet, Jesus tuke brede and blessit and brak, and gafe to his disciplis, an said, Tak ye, and ete ye. This is my body. And he tuke the cup, and did thankingis, and gafe to thame and said, Drink ye all hereof. This is my bluide of the new testament, quilk salbe sched for mony into remissioun of sinnis. And I say to you, I sal nocht drink fra this thyme of this kynde of wyne, til into that day quhen I drink it anew with you in the kingdom of my fader.

b. The same passage in the Bassendyne or Geneva Bible

Transcript

And as they did eat, Jesus toke the bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and gave it to the disciples, and said, Take eat, this is my bodie. Also he toke the cup and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, Drinke ye all of it. For this is my blood of the Newe Testament, that is shed for mannie for the remission of sinnes. I say unto you that I will not drinke hence forthe of this fruit of the vine until that day, when I shal drinke it newe with you in my Father’s kingdome.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your notes might be different.

Remembering that behind both passages is a common source text, it is still interesting to see how the two versions are mutually comprehensible, and yet significantly different. The main differences are due to the character of spoken Scots in that period – ‘and quhen they soupet’.

The Genevan English is slightly more formal, and of course more familiar as it is clearly the forerunner of the later English Bible, which was formally established in the Authorised Version published in 1611, commissioned by James VI of Scotland and I of England. However, Nisbet’s version is more to the point, more personal and ‘down to earth’, directly relating to the general public and the way these people used Scots at the time.

As discussed above, the Bible or sacred text – the BUIK – sits alongside the liturgies or services of worship. The Genevan Church also produced a book of liturgies giving instructions and further texts applicable to most religious occasions, while excluding festivals such as Easter and Christmas, which they believed had no precedent in the Bible.

John Knox and his Scottish colleagues endorsed this Book of Common Order and had it published in Edinburgh, again in an English version which had been developed by Knox’s English speaking congregation in Geneva. The Book of Common Order was also translated into Gaelic on the instruction of Bishop John Carswell of Argyll, becoming the first printed book in Scottish Gaelic. But the Scots language received no recognition or expression in these official texts of the Scottish Protestant Reformation.

The Book of Common Order, as published in Scotland in 1562, cites the passage from the Apostle Paul in the New Testament on which the Protestants based their version of Holy Communion – the Lord’s Supper. This is clearly related to the passage quoted in Activity 5 in Matthew’s Gospel, and may derive ultimately from a shared oral tradition.

The Lorde Jesus, the same night he was betrayed, toke bread, and when he had geven thankes, he brake it, saying, Take ye, eate ye, this is my bodie which is broken for you; doo this ion remembrance of me. Likewise after supper he toke the cuppe, saying, This cuppe is the newe Testament or covenant in my bloude, doo ye this so ofte as ye shall drinke therof, in remembrance of me. For so ofte as ye shall eate this bread and drinke of this cuppe, ye shall declare the Lordes death until his comminge.

Here is a recording of this passage to help you get a feel for the rhythm and sound of this version in Medieval English.

Transcript

The Lorde Jesus, the same night he was betrayed, toke bread, and when he had geven thankes, he brake it, saying, Take ye, eate ye, this is my bodie which is broken for you; doo this ion remembrance of me. Likewise after supper he toke the cuppe, saying, This cuppe is the newe Testament or covenant in my bloude, doo ye this so ofte as ye shall drinke therof, in remembrance of me. For so ofte as ye shall eate this bread and drinke of this cuppe, ye shall declare the Lordes death until his comminge.

The influence of this written text of 1562 persists to this day in the services of the Protestant Church of Scotland, and the Free Presbyterian Churches, exposing the widely shared misconception that the Presbyterians had no set prayers or liturgies. Equally, that continuity demonstrates the influence of the liturgy in excluding Scots as an official language for religious purposes.

Activity 6

Now compare the passage from The Book of Common Order in English – as seen above – with Nisbet’s version of the same passage in Scots.

Part 1

Listen to the same passage from Nisbet’s version in Scots. You may also want to record yourself reading this out and then compare your version with our model.

Transcript

Listen

For the Lord Jesu, in qhat nycht he was betrayit, tuke brede, and did thankingis, and brak, and said, Tak ye, and ete ye; This is my bodie, quilk shalbe betrait for you; do this thynge into my mynde. Alsa the cup, eftere that he had soupit, and said, This cuip is the newe testament in my blude; do ye this thing, als aft as ye sal drink, into my mynde. For als afty as ye sal ete this brede and sal drink the chalice, ye sall tell out the dede of the Lord, till that he cum.

Model

For the Lord Jesu, in qhat nycht he was betrayit, tuke brede, and did thankingis, and brak, and said, Tak ye, and ete ye; This is my bodie, quilk shalbe betrait for you; do this thynge into my mynde. Alsa the cup, eftere that he had soupit, and said, This cuip is the newe testament in my blude; do ye this thing, als aft as ye sal drink, into my mynde. For als afty as ye sal ete this brede and sal drink the chalice, ye sall tell out the dede of the Lord, till that he cum.

Activity 7

This second section of unit 15 mentions a number of people who were influential in religious reforms and translations of the Bible in the 16th century. In this activity, you will be able to remind yourself of the most prominent 16th century reformers and their contribution.

The names of the reformers are listed in the order in which they appear in this section.

- a.Without reading the section again, match the names with their achievements.

- b.Once you have completed the matching exercise, you might want to revisit section 2 and take a note of any other important aspects relating to the reformers mentioned here.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

-

Martin Luther

-

William Tyndall

-

John Hamilton

-

Murdoch Nisbet

-

John Knox

-

James VI of Scotland

-

John Carswell

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Roman Catholic, wrote an influential Catechism in Scots

b.Protestant Reformer, secretly translated Bible into Scots

c.Protestant Reformer, made an English Bible translation the norm in Scotland

d.Protestant Reformer, translated The Book of Common Order into Scottish Gaelic

e.Protestant Reformer, translated Bible into vernacular language

f.Protestant, commissioned Authorised English Version of the Bible

g.Protestant Reformer, translated Bible into vernacular language

- 1 = e,

- 2 = g,

- 3 = a,

- 4 = b,

- 5 = c,

- 6 = f,

- 7 = d

15.2 The impact of Anglicisation on religious language in Scotland

It took fifty years, and much longer in the Highlands, before the full impact of this Anglicisation of religious language was felt. Also, although the Presbyterians advocated a ‘pure’ form of Christianity, ‘uncontaminated’ by human customs and traditions, which they labelled ‘idolatrie’, this aim was in effect impossible. Religion continued to be an important social activity in which Scots-speaking families and communities participated. People also continued to argue about religion and to sing religious songs, despite attempts to keep both within strict limits!

In fact, Protestant sympathisers had already harnessed popular Scots culture to the cause, in the shape of Sir David Lindsay’s Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis, which you came across in unit 9. This innovative drama, which developed in the 1540s–50s, begins in the world of the medieval morality play, moves into a practical contemporary agenda for religious and political reform, and then culminates in foolerie and farce.

Scots is the essential medium throughout, and when in 1948 an adaptation of Lindsay’s Satyre headlined the Edinburgh International Festival, a dynamic connection was formed between Scots dramatic traditions and the modern literary renaissance.

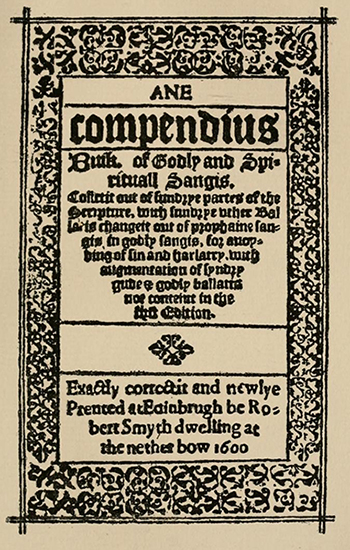

In 1567, Protestant Reformers published a collection of sacred songs combining Protestant inclined lyrics with Scottish folk melodies. These Gude and Golie Ballatis were in due course to lead to a Scottish Psalter and the Paraphrases, which were scriptural texts, in English, adapted into regular metre for singing. But initially the mix was much broader and some texts survive which are clearly carols.

There may even be an inheritance here from the medieval Mystery Plays, which were performed in Scottish towns in the 15th and 16th centuries. Again, the Scots character of the lyrics reflects their social context and the continuing role of Scots as a medium for spoken word and song as exemplified in this extract from The Conceptioun of Christ as printed in the Gude and Golie Ballatis (pp. 83–4):

Let us rejoyce and sing,

And praise that michtie King,

Qhuilk send his Sone of a Virgin bricht.

La. Lay. La.

And on him tuke our vyle nature,

Our deidlie woundis to cure,

Mankynde to hald in richt.

La.lay.La …….

Thou blyssit Virgin mylde,

Thou sall consave an Chylde

The pepill redeem sall he:

La.Lay.La.

Here is a recorded version of this extract and you might want to read along while listening to practise your spoken Scots.

Transcript

Let us rejoyce and sing, And praise that michtie King, Qhuilk send his Sone of a Virgin bricht. La. Lay. La. And on him tuke our vyle nature, Our deidlie woundis to cure, Mankynde to hald in richt. La.lay.La ……. Thou blyssit Virgin mylde, Thou sall consave an Chylde The pepill redeem sall he: La.Lay.La. Here is a recorded version of this extract and you might want to read along while listening to practise your spoken Scots.

As the Calvinist purists gained influence, carols about the Virgin Mary were squeezed out and Christmas was demoted. But even Calvinism could not prevent people expressing religious sentiments in their own language. John Knox himself was criticised by Ninian Winzet, the Linlithgow schoolmaster, for deserting ‘our auld plane Scottis qhuilk your mother lerit you […] I am nocht acquyntit,’ continues Winzet, ironically, ‘with your Southeroun’ i.e. your Anglicised speech. With this appeal to linguistic identity, Winzet is trying to characterise Protestant reform as based on ideas alien to Scottish society and tradition. In the end, Winzet himself was to spend much of the rest of his own life in exile in southern Germany (Ninian Winzet (ed) (1835) Certane Tractatis for Reformation of Doctryne and Maneris in Scotland, Edinburgh, p. 54).

Unfortunately, we have no evidence of how the Protestant preachers deployed language in their pulpits. Certainly if sermons came to be published they moved increasingly towards written English, but it is hard to imagine that Scots was not deployed for rhetorical impact. Religious tensions continued after the Reformation in Scotland, between Presbyterians and Episcopalians, Scotland's main religious groups, over such issues as Church government, state oaths and nonconformity.

This was about competing visions of Presbyterianism, disputes that were satirised by Robert Burns is poems such as ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ and ‘The Holy Fair’.

![]()

You may want to listen to ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ as read by famous British actor Richard Wilson on the BBC Bitesize website. This has been created for Scottish students sitting their exams. ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ is one of many texts studied in Scottish schools. There are also Study Notes which analyse the themes and the language used by Burns.

15.3 The path to Lorimer’s translation

In the 19th century strictly orthodox Calvinism was on the wane in mainstream Protestant churches, and some people began to openly regret the division between the official religious register of formal English and the spoken language of a great many people sitting in the pews: Scots.

A series of translators worked to provide Scots versions of bible books or selected passages, including Henry Scott Riddell, George Henderson, P. Hately Waddell and James Murray, who was to become the Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. Finally in 1901 William Wye Smith, a Scots American, published a complete New Testament in Braid Scots, which broke fresh ground by working from more recent English translations, and attempting to imitate the language of Burns rather than the medieval poets.

Although Smith reached a broader public market, his work has been criticised by Graham Tulloch, the leading historian of the Bible in Scots for being inconsistent and not sufficiently colloquial. Burns himself combined literary and colloquial Scots with literary English in his poetry, and the Authorised Version of the Bible is a strong stylistic influence, as in much Scottish Literature.

Inspired by the Scottish Literary Renaissance of the 20th century, W. L. Lorimer, a noted classicist and Scots linguist, embarked on a fresh translation of the New Testament from the original Greek into Scots. Published in 1983, Lorimer’s New Testament was instantly hailed as a classic work of translation in any language. The first words of Lorimer’s version of Paul’s paean to love in I Corinthians 13 are inscribed at the gate of the members’ entrance to the Scottish Parliament, making it one of the most recent Scots inscriptions in Scotland’s capital city:

Gin I speak wi the tungs o men an angels, but hae nae luve I my hairt, I am no nane better nor dunnerin bress or a ringin cymbal. Gin I hae the gift o prophecie, an am acquent wi the saicret mind o God, an ken aathing ither at man may ken, an gin I hae siccan faith as can flit the hills frae their larachs - gin I hae aa that but hae nae luve in my hairt, I am nocht.

Activity 8

In this activity, you will work more closely with the inscription on the Scottish Parliament building from Lorimer’s Bible translation into Scots. This time, you will focus on the vocabulary used by Lorimer.

Part 1

Match the Scots words with their English equivalents.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

-

dunnerin bress

-

acquent

-

aathing ither

-

siccan

-

flit

-

larach

-

nocht

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.such/like

b.resounding gong

c.all/everything

d.move/shift

e.place/foundation

f.nothing

g.knowing/being acquainted with

- 1 = b,

- 2 = g,

- 3 = c,

- 4 = a,

- 5 = d,

- 6 = e,

- 7 = f

Part 3

Finally, listen to a recording of the first words of I Corinthians 13 and then record yourself reading these words.

Transcript

Listen

Gin I speak wi the tungs o men an angels, but hae nae luve I my hairt, I am no nane better nor dunnerin bress or a ringin cymbal. Gin I hae the gift o prophecie, an am acquent wi the saicret mind o God, an ken aathing ither at man may ken, an gin I hae siccan faith as can flit the hills frae their larachs - gin I hae aa that but hae nae luve in my hairt, I am nocht.

Model

Gin I speak wi the tungs o men an angels, but hae nae luve I my hairt, I am no nane better nor dunnerin bress or a ringin cymbal. Gin I hae the gift o prophecie, an am acquent wi the saicret mind o God, an ken aathing ither at man may ken, an gin I hae siccan faith as can flit the hills frae their larachs - gin I hae aa that but hae nae luve in my hairt, I am nocht.

Language links

In the extract from Lorimer’s Bible translation you came across the word dunnerin, which in English means ‘thundering/noisy/resounding’. This Scots word has close connections with the German language. It derives from the Scots noun dunner, which in modern German is Donner. There is, however, a Scots verb with the same spelling as the German noun, which means being stunned by din, a loud noise.

However, Lorimer’s huge literary achievement is also a weakness, because his recovery of centuries of Scots is rich beyond the reach of contemporary spoken idiom. It was left to the retired actor and social worker Jamie Stuart to strike a more accessible note.

Stuart was, before his death in 2016, the last surviving member of the cast of the 1948 revival of Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis. His A Scots Gospel, published in 1985, is the text of a dramatic retelling of the Gospel story, based on his own live performance, and drawn from all four New Testament Gospels. Stuart makes good use of all his predecessors, including Lorimer, and found a ready market for both performances and text. Encouraged by this he achieved even greater popularity with his similarly constructed Glasgow Bible, which went through numerous reprintings as well as audio and video versions.

The drama aspect is significant, as performances outwith or alongside standard church services provided the best opportunities for Scots usage in religion. These events were often connected with revived festivals such as harvest or, most popular of all, Christmas Nativities, which also take place in many primary schools. Here is a typical extract from a Nativity, In the Beginnin (Smith, 1994), produced for churches and schools by The Netherbow Arts Centre. Colloquial idiom and local variants are both actively encouraged, yet this is recognisably a continuation, or renewal, of Scots language in a religious context.

Here is the audio recording of an extract from the play – we are sure you will recognise the well-known scene. Note the meaning of the following words that appear in the recording: lift (sky), dwined (faded away) and clishmaclavers (gossip). You might want to try reading this yourself to practise your spoken Scots. You can read the text of the Nativity play in full on the Church of Scotland website, where you can appreciate how the use of the Scots language once again brings religion to life for the people by establishing a link to their own sense of identity.

Transcript

Listen

Model

15.4 What I have learned

Activity 9

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- how Protestant reformers translated the Bible into commonly spoken or vernacular languages

- the Bassendyne Bible of 1579 – the first non-Latin Bible to be printed in Scotland

- the impact of The Book of Common Order not being in Scots

- the effects of Anglicisation

- the Gude and Golie Ballatis

- the publication in 1901 of the New Testament in Braid Scots, which attempted to imitate the language of Burns rather than the medieval poets

- Lorimer’s translation of the New Testament from Greek into Scots.

Further research

You might want to find out some more about Murdoch Nisbet’s work and Bible translation into Scots. Read:

- The Introduction to the historical source text publication by Blackwood & Co (1901), pp. vii-xxxv.

- Mark Thomson’s article on Nisbet’s work and its importance for the Scots language.

Have a look at the full edition of the Gude and Godlie Ballatis in the archives of the National Library of Scotland, which contains an interesting introduction about vernacular hymns in England and Scotland as well as the origins of this book of psalms and songs.

To find out more about the Reformation in Scotland, consult the following resources:

- the section on the Scottish Reformation on BBC’s Scotland’s History site;

- this article on John Knox and a timeline of Scottish Reformation on the Presbyterian Scottish Church’s Reformation History site;

- this information in the Encyclopaedia Britannica on the Reformation in England and Scotland;

Education Scotland commissioned an animated History of the Scots language. Watch for the inclusion of William Lorimer and what is described in the video as “the most ambitious translation project ever undertaken into Scots”.

The ‘History of Scots’ animated video above also comes with a PDF document which takes you to different examples of written Scots.

These examples of Scots have also been recorded for listening. The audios are made up of readings in Scots from various eras in Scotland's history. The recordings were done in 2016 in partnership between Education Scotland and The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS). The performers reading were students at the RCS. They were coached by Jean Sangster, Head of Voice and the Centre for Voice in Performance at RCS. The readings were recorded in the RCS Recording Studio by Recording Studio Engineer Bob Whitney. It is recommended you read and listen to all the passages and recordings.

Explore the obituary page for Jamie Stuart on the Church of Scotland website.

Now go on to Unit 16: Scots abroad.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Whalsay kirk and graveyard: David Purchase - geograph.org.uk/p/5021246 - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Scottish Storytelling Centre: Brian McNeil - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scottish-Storytelling-Centre_2014-07-17~_MG_0036.jpg - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Murdoch Nisbet's manuscript translation of the New Testament: Thomas L. King - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Murdock_Nisbet%27s_manuscript_translation_of_the_New_Testament.jpg - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Photograph of The Scottish Parliament: Sara Rasmussen - https://www.flickr.com/photos/54226721@N03/5829166683 - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/