Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 7:44 AM

Unit 18: Literature – poetry

Introduction

In this unit, you will learn more about poetry in the Scots language. There are samples of poems representing dialect diversity across various parts of the country, from Shetland, the Borders, the North East, to each of Scotland’s cities. All are different but connected to each other.

There is also a range of Scots evident in poetry throughout Scotland’s history, from major poets of different periods, such as William Dunbar, Elizabeth Melville, Robert Burns, Hugh MacDiarmid, Christine de Luca and Gerda Stevenson, some of whom you have already come across in this course. This unit will introduce you to how poetry works in Scots and how the language itself offers particular opportunities for distinctive poetic expression.

The first thing to emphasise is that all poetry is a transformation of everyday language into something more highly sensitised than its normal use. Also, there are many different forms of poem: a sonnet has a distinct structure, a ballad is usually a song that tells a story in verse in four-line rhyming stanzas, a monologue may be in free verse, an epic such as Gavin Douglas’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, touched upon in unit 15, tells a long story through a number of books and involves numerous characters, men and women in dramatic situations, taking the form of an extended narrative with many digressions.

In any single case, the Scots language can suggest tones of voice, utilise aspects of enunciation, vocal and verbal expressions, present or suggest characters, represent tension, harmony, discord, sorrow or joy, and ultimately it can create meaning in poems in ways no other language can – or rather, it does so just as all languages do, but in its own distinctive ways. The lack of a ‘standard’ Scots may be an advantage to writers from different locations whose voices and hearing have become attuned to the sounds of their favoured or native territories.

Sydney Goodsir Smith (1915–75) was born in New Zealand but adopted and adapted Scots in many of his best poems. In ‘Epistle for John Guthrie’ he made the point that all poems, all works of art, are the result of artifice: they are made things. Here, speaking of the antipathy towards Scots language in many quarters, he stated the following:

Transcript

We’ve come intil a gey queer time

When screivin Scots is near a crime,

‘There’s no one speaks like that’, they fleer,

– But wha the deil spoke like King Lear?

(2010[1975])

A general guide for you to reading any poem is to think of the word ‘sift’ and apply it as an acronym like this:

- Subject: what is it about?

- Imagery: what are the main images it evokes?

- Form: what structure does it take?

- Tone: how does it sound?

Like any poem in any language, poems in Scots might take any subject, imagery and form but their tone is particularly affected by the language. In a poem, meaning is usually conveyed through sound as well as structure, imagery and subject. These component parts all work together, so what characterises one changes all the others. Throughout this unit, you will be working with this approach as you explore how the Scots language shaped much of the poetry of Scotland.

Important details to take notes on throughout this unit:

- the range of vernacular dialects and the synthesis of dialects in crafted, literary Scots poems

- the range of forms in literary Scots poems and the relation between voice (or voices) and poetic form (or forms) through history

- ways of saying (forms of address: who is being talked to, what is the position of the reader and what is the position of the writer?)

- the distinctive or ‘untranslatable’ characteristics of poetry in Scots.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

18. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: One who fashions, constructs, produces, prepares, etc.

Example sentence: “Pairlament walcomes the annual celebration o Scotland’s national makar, Robert Burns...”

English translation: “Parliament welcomes the annual celebration of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns...”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Pairlament walcomes the annual celebration o Scotland’s national makar, Robert Burns.

Model

Pairlament walcomes the annual celebration o Scotland’s national makar, Robert Burns.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Language Links

The word makar is a Scots term for poet, literally, a ‘maker of poems’. The craft as well as the art suggested by the term is important because it emphasises that poems are made for a purpose, and many poets before the Romantic era (c.1770–1830) had specific purposes in mind.

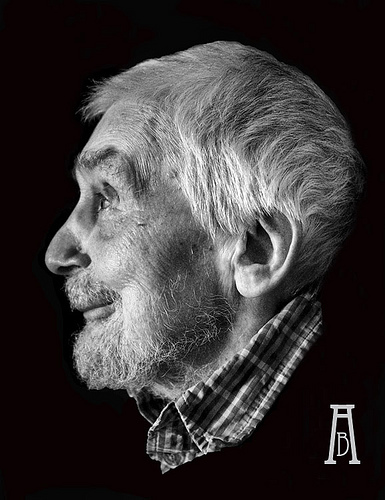

In the Medieval and Renaissance world, all art was didactic, and the major Scots language poets of c.1425–1550, Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Gavin Douglas and David Lyndsay, all had things to teach their readers. They also had defined social roles, at court, in the church or as teachers. The word ‘Makar’ was revived among our contemporaries when Edwin Morgan was appointed the first ‘Scots Makar’ in 2004. He was followed by Liz Lochhead in 2011 and Jackie Kay in 2016. Morgan expressed some concern that the term suggested something antiquated but he and his successors came to welcome it as distinctively Scottish, as opposed to the designation ‘Poet Laureate’.

Each of these modern poets used their role in this public office to write on public events and political change that affected people, generally in Scotland. The Romantic idea of the isolated voice, lyrically speaking of personal experience, was less important than the social location of a poet speaking on behalf of, and addressing a wider public. This was exemplified in Morgan’s poem for the opening of the Scottish parliament in 2004, ‘Open the Doors!’.

The poem is mainly in English but uses Scots phrases when declaring what people do not want of their politicians: ‘What do the people want of the place?’ he asks:

‘A nest of fearties is what they do not want.

A symposium of procrastinators is what they do not want.

A phalanx of forelock-tuggers is what they do not want.

And perhaps above all the droopy mantra of “it wizny me” is what they do not want.’

Related word:

Definition: Twisted, crooked, perverse, bad-tempered, oppositional

Example sentence: “Mony eens hiv windered if Stevenson insistit oan scrievin his story ‘Thrawn Janet’ in Scots cause it is a folk tale...”

English translation: “Many people have wondered if Stevenson insisted on writing his story ‘Thrawn Janet’ in Scots because it is a folk tale...”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Mony eens hiv windered if Stevenson insistit oan scrievin his story ‘Thrawn Janet’ in Scots cause it is a folk tale.

Model

Mony eens hiv windered if Stevenson insistit oan scrievin his story ‘Thrawn Janet’ in Scots cause it is a folk tale.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Hugh MacDiarmid’s poem ‘The Sauchs in the Reuch Heuch Hauch’ contains the word ‘thrawn’ which here suggests a quality of devilish twistedness, a refusal to obey authority. In the poem, the people (‘we’) might ‘come doon’ from stormy moods of anger, intoxication, passion, troubled feelings, and settle down gently ‘like a bird i’ the haun’’ but these sauchs – willow trees, twisted out of shape by prevailing winds – are unchanging and unpersuadable in their opposition to any establishment power.

18.1 The range of Scots dialects in three poems

This section will focus on three poems representing different forms of the Scots language from their own geographical territories: Shetland, the North East, and Ayrshire. These poems draw on the idioms and speech forms their authors grew up with and became intimately familiar with as sound-patterns in their childhood.

The question they raise is one of authenticity. When a poet uses their own native language, is that more ‘authentic’ than when a poet uses Scots words and phrases taken from other writers or even straight out of the dictionary? There is also the question of authority and self-confidence. If a poem works, how confident we may feel about its authority will be endorsed. If it seems inauthentic, we inevitably feel more uncertain about the authority of its language.

Over centuries, Scots has been subject to these questions, often resulting in uncertainty and lack of confidence. To many English-language readers and writers, Scots still seems merely eccentric. Yet if we’ve seen (especially with ‘The Sauchs in the Reuch Heuch Hauch’) that the rebarbative aspect of the language can enhance the meaning of a poem, we should begin by giving the benefit of the doubt to the poets writing in Scots.

To investigate this, we’ll start with one of Shetland’s finest native writers, J.J. Haldane Burgess (1862–1927), blind poet, novelist, violinist, historian and linguist, who assisted Jakob Jakobsen’s research into the Norn language in Shetland.

Activity 4

You have come across the Shetland dialect of Scots a number of times already. In this activity, you will work with it again, this time focusing on how this dialect shapes this poem and its meaning.

Part 1

Listen to the poem and simply enjoy the sound of the words of the poem read by Bruce Eunson, who himself is from Shetland. Which feature of the dialect stands out to you in the way in which it makes the poem sound?

As always, once you have listened, read out the poem yourself and record your rendition - try to emulate the Shetland dialect, if you can, following Bruce Eunson’s example.

Transcript

Listen

Da Blyde-Maet

Whin Aedie¹ üt² da blyde-maet³ for himsell

An her, pür lass, ’at dan belanged ta him,

Whin nicht in Aeden wis a simmer dim

Afore he wis dreeld oot ta hok an dell,

Hed he a knolidge o da trüth o things,

Afore da knolidge koft wi what’s caa’d sin?

Afore da world raised dis deevil’s din,

Heard he da music ’at da starrins sings?

Some says ’at Time is craalin laek a wirm

Troo da tik glaar⁴ dey caa Eternity,

A treed o woe an pain it aye mann be

’At Fate reels aff frae ever fleein pirm⁵

Bit Joy an Hopp in aa dis life I see,

It’s plain anyoch ta see ta him ’at’s carin,

T’o Time is spraechin⁶, laeck a fraeksit⁷ bairn,

Ipo da bosim o Eternity.

We’se aet da blyde-maet yet, an it sall be

O mony anidder, deeper, graander life,

An Time sall learn troo aa dis weary strife

Ta sook da fu breests o Eternity.

Model

Da Blyde-Maet

Whin Aedie¹ üt² da blyde-maet³ for himsell

An her, pür lass, ’at dan belanged ta him,

Whin nicht in Aeden wis a simmer dim

Afore he wis dreeld oot ta hok an dell,

Hed he a knolidge o da trüth o things,

Afore da knolidge koft wi what’s caa’d sin?

Afore da world raised dis deevil’s din,

Heard he da music ’at da starrins sings?

Some says ’at Time is craalin laek a wirm

Troo da tik glaar⁴ dey caa Eternity,

A treed o woe an pain it aye mann be

’At Fate reels aff frae ever fleein pirm⁵

Bit Joy an Hopp in aa dis life I see,

It’s plain anyoch ta see ta him ’at’s carin,

T’o Time is spraechin⁶, laeck a fraeksit⁷ bairn,

Ipo da bosim o Eternity.

We’se aet da blyde-maet yet, an it sall be

O mony anidder, deeper, graander life,

An Time sall learn troo aa dis weary strife

Ta sook da fu breests o Eternity.

Answer

This is a model answer, your answer might be different.

To me, being a non-native speaker of neither Scots nor English, the poem has a strong resemblance with Scandinavian languages, especially through the way in which vowels are much more prominent than in Standard English, often pronounced as long vowels. This is reflected in the many long ‘a’-sounds (the ɑːin the phonetic alphabet) as in lass, dan, caa’d; the way in which the ‘o’ is pronounced as a long ɔ: in afore, o, mony; the long u: as in troo or sook.

Another two vowels stand out for me, on the one hand, because these do not exist as such in English. When written, they are: ü in üt or pür, and ae in maet, spraechin, laeck or fraeksit. When spoken the ü is very much like the Danish ø sound, and the ae reminds me of the Danish æ or the way in which the German ä is pronounced. These sounds add a strong sense of musicality to the language in combination with the different intonation and rhythm from English or other Scots dialects, more like a slow sing-song where the vowels are allowed to stand out and linger.

Part 2

Now read the poem and the translation into English and consider again how the Shetland Scots of the poem contributes to the meaning of the poem.

Da Blyde-Maet

Whin Aedie¹ üt² da blyde-maet³ for himsell

An her, pür lass, ’at dan belanged ta him,

Whin nicht in Aeden wis a simmer dim

Afore he wis dreeld oot ta hok an dell,

Hed he a knolidge o da trüth o things,

Afore da knolidge koft wi what’s caa’d sin?

Afore da world raised dis deevil’s din,

Heard he da music ’at da starrins sings?

Some says ’at Time is craalin laek a wirm

Troo da tik glaar⁴ dey caa Eternity,

A treed o woe an pain it aye mann be

’At Fate reels aff frae ever fleein pirm⁵

Bit Joy an Hopp in aa dis life I see,

It’s plain anyoch ta see ta him ’at’s carin,

T’o Time is spraechin⁶, laeck a fraeksit⁷ bairn,

Ipo da bosim o Eternity.

We’se aet da blyde-maet yet, an it sall be

O mony anidder, deeper, graander life,

An Time sall learn troo aa dis weary strife

Ta sook da fu breests o Eternity.

Vocabulary help:

- Adam

- ate

- glad-food, eaten when a woman first rises from child-bed

- slime

- pirn

- screaming

- fractious

Answer

This is a model answer, your answer might be different.

If we translated this poem into English it might read as follows:

The Glad-Food (the meal eaten when a woman first rises from child-bed)

When Adam ate the glad-food for himself / And she, poor lass, who then belonged to him, / When night in Eden was a summer twilight / Before he was evicted, / Had he a knowledge of the truth of things, / Before the knowledge tainted with what’s called sin? / Before the world raised this devil’s noise, / Did he hear the music that the stars sing? / Some say that Time is crawling like a worm / Through the thick slime they call Eternity, / A thread of woe and pain it always must be / That Fate reels off from the ever turning pirn. // But Joy and Hope in all this life I see, / It’s plain enough to see by he who cares, / Though Time is screaming like a fractious child, / Upon the bosom of Eternity. / We shall eat the glad food yet, and it shall be / Of many another, deeper, grander life, /And Time shall learn through all this weary strife / To suck the full breasts of Eternity.

The language of the original is deeply connected to the Shetland location where Haldane Burgess lived, but the subject of the poem is universal. It begins with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, about to take on the burden of the Tree of Knowledge and set out from ‘Eternity’ into a world of Time and ‘weary strife’.

Despair and tragic loss is hauntingly present in the poem, but appetite and a defiant will to embrace the ‘graander life’ in the world at large is the poem’s final, optimistic assertion of value and hope. This balance of loss and hope provides a tension and dramatic structure to the poem. It begins with the word ‘Whin’ (‘When’) which always implies that more than one thing is going on at the same time. (‘When this happened, this was also happening…’)

So there’s a suspenseful element in the structural unfolding of the poem. There’s also a distinctively Shetland idiom in the language so that the universal – or specifically Christian – story it tells implies a local application. And that is emphasised by the oral, immediate aspect of the sounds and tones of the vocabulary used. This is not a vatic pronouncement but a colloquial utterance conveyed with great authority.

Activity 5

Now go to the North East and consider a very different poem, a song, in fact, The Wild Geese by Violet Jacob, who was born in Montrose as the daughter of the 18th laird of Dun and who later married an officer. However, despite her social standing, “Jacob had great sympathy with the lives of others, especially those who were not blessed in their lot – the poor, the put-upon, the vagrants. She had a keen eye, too, for the age-old inequalities in the relationships between men and women, giving a voice…” (Scottish Poetry Library, 2012) to the unheard.

Part 2

As a second step, listen to Jacobs’ song being performed. There are two easily available versions, one by Jim Reid and the other by Jean Redpath. Listen to both versions, again paying attention to the sound of the Scots dialect reflected in the words of the poem, to the melody not just of the song but also of the language. Jim Reid’s version has a stronger East-Coast feel and you will again notice the strong long vowels, which you have come across in Haldane’s poem.

The range of Scots dialects in three poems – continued

Activity 6

A very different kind of poem is the monologue by Gerda Stevenson, ‘The Abdication of Mary Queen of Scots’ (though a sense of loss is present here too). The poet from the Scottish Borders wrote this poem in 2014 in response to a painting (1773) of the same title by Gavin Hamilton, exhibited in the collection of the Hunterian art gallery at Glasgow University. View the painting.

Part 2

Finally, reread the poem, preferably out loud, and ask if there are specific words and phrases in the poem that seem especially effective? How is this effect delivered?

Transcript

Listen

The Abdication of Mary Queen of Scots

Tak ma croon, an dinna fash –

aa yon wis ower fur me lang syne.

Ye needna glaum at ma silk goon

wi yer coorse nieve – I’m nae threit;

I’ll sign yer muckle scroll, dae whit I maun,

past carin noo; thae last three days ma flesh

an saul hae wandert shores o hell-fire, dule an daith:

twa bairns I cradled in ma wame aa through the months,

sae douyce, o Spring an Simmer, slippit cauld an stieve

intae the dowie air o Leven’s grey stane waas,

claucht frae ma jizzen, an burriet ootby, wi nae prayer,

fur aa I ken, an nae sang, twa scraps o heiven,

aa ma howp in their twin licht smoorit noo,

tho milk’s aye buckin frae ma breists unner ma lace an steys;

an I couldnae gie a fig fur yer fouterin laws,

sat there, scrieven yer Latin clatters o queens an kings –

O, I could run rings roon ilka yin o ye in Greek an aa,

as weel’s ma bonnie French, but ye’re naethin, naethin noo,

juist ghaists; an, och, Mary, Mary Seton, last

o ma fower leal ladies, dinna waste yer tears

on gien up a bittie gowd an glister, haud ma airm

if it helps, but dinna, dinna greet fur this.

Model

The Abdication of Mary Queen of Scots

Tak ma croon, an dinna fash –

aa yon wis ower fur me lang syne.

Ye needna glaum at ma silk goon

wi yer coorse nieve – I’m nae threit;

I’ll sign yer muckle scroll, dae whit I maun,

past carin noo; thae last three days ma flesh

an saul hae wandert shores o hell-fire, dule an daith:

twa bairns I cradled in ma wame aa through the months,

sae douce, o Spring an Simmer, slippit cauld an stieve

intae the dowie air o Leven’s grey stane waas,

claucht frae ma jizzen, an burriet ootby, wi nae prayer,

fur aa I ken, an nae sang, twa scraps o heaven,

aa ma howp in their twin licht smoorit noo,

tho milk’s aye buckin frae ma breists unner ma lace an steys;

an I couldnae gie a fig fur yer fouterin laws,

sat there, scrieven yer Latin clatters o queens an kings –

O, I could run rings roon ilka yin o ye in Greek an aa,

as weel’s ma bonnie French, but ye’re naethin, naethin noo,

juist ghaists; an, och, Mary, Mary Seton, last

o ma fower leal ladies, dinna waste yer tears

oan gien up a bittie gowd an glister, haud ma airm

if it helps, but dinna, dinna greet fur this.

18.2 A brief and very concise history of poetry in Scots

In this this section, you are going to work with three examples of poetry in Scots from across the centuries, not to attempt a comprehensive overview but to gain a sense of the historical longevity and quality of Scots-language poetry. The literary history of the Scots language can still be recognised in dialect forms of Scots today. There are some key aspects that you will come across, namely that:

- Courtly forms prevailed in some of the earliest examples of Scots poetry and are still in use, though not at court.

- At different periods in history, poetry in Scots was revived, both by a renewed effort to write new poems and a self-conscious reappraisal and republishing of older Scots poetry for a new generation of readers.

- Scots poems can be formal or informal, cool and restrained or impassioned and forceful: there is no prescription in terms of provenance or legitimacy, other than the capacity of the reader to engage with them.

Activity 7

In this activity you will work with very different kinds of poems from the 15th, 17th and 21st centuries. As in previous activities, you will read the poems and analyse their subject, imagery, form, and tone. This time, you will also compare and contrast the poems with each other in relation to their subject, imagery, form, and tone. As in previous activities, you will be able to listen to the poems and engage closely with the sound and rhythm of the Scots language the poets used and how it impacts on the reader’s/listener’s meaning making of the texts.

Part 1

1. William Dunbar (c.1460-c.1520) ‘To a Ladye’

a. Read and analyse the poem using the SIFT questions from the introduction.

Sweit rois of vertew and of gentilnes,

Delytsum lyllie of everie lustynes,

Richest in bontie and in bewtie cleir

And euerie vertew that is deir

Except onlie that ye ar mercyles.

In to your garthe this day I did persew.

Thair saw I flowris that fresche wer of hew,

Baithe quhyte and rid, moist lusty wer to seyne,

And halsum herbis vpone stalkis grene,

Yit leif nor flour fynd could I nane of rew.

I dout that Merche with his caild blastis keyne

Hes slayne this gentill herbe that I of mene,

Quhois petewous deithe dois to my hart sic pane

That I wald mak to plant his rute agane,

So confortand his levis vnto me bene.

b. Listen to the poem.

Transcript

Listen

Sweit rois of vertew and of gentilnes,

Delytsum lyllie of everie lustynes,

Richest in bontie and in bewtie cleir

And euerie vertew that is deir

Except onlie that ye ar mercyles.

In to your garthe this day I did persew.

Thair saw I flowris that fresche wer of hew,

Baithe quhyte and rid, moist lusty wer to seyne,

And halsum herbis vpone stalkis grene,

Yit leif nor flour fynd could I nane of rew.

I dout that Merche with his caild blastis keyne

Hes slayne this gentill herbe that I of mene,

Quhois petewous deithe dois to my hart sic pane

That I wald mak to plant his rute agane,

So confortand his levis vnto me bene.

Model

Sweit rois of vertew and of gentilnes,

Delytsum lyllie of everie lustynes,

Richest in bontie and in bewtie cleir

And euerie vertew that is deir

Except onlie that ye ar mercyles.

In to your garthe this day I did persew.

Thair saw I flowris that fresche wer of hew,

Baithe quhyte and rid, moist lusty wer to seyne,

And halsum herbis vpone stalkis grene,

Yit leif nor flour fynd could I nane of rew.

I dout that Merche with his caild blastis keyne

Hes slayne this gentill herbe that I of mene,

Quhois petewous deithe dois to my hart sic pane

That I wald mak to plant his rute agane,

So confortand his levis vnto me bene.

2. Anonymous ballad ‘The Twa Corbies’

a. Read and analyse the poem using the SIFT questions from the introduction.

As I was walking all alane

I heard twa corbies making a mane:

The tane unto the tither did say,

'Whar sall we gang and dine the day?'

'—In behint yon auld fail dyke

I wot there lies a new-slain knight;

And naebody kens that he lies there

But his hawk, his hound, and his lady fair.

'His hound is to the hunting gane,

His hawk to fetch the wild-fowl hame,

His lady 's ta'en anither mate,

So we may mak our dinner sweet.

'Ye'll sit on his white hause-bane,

And I'll pike out his bonny blue e'en:

Wi' ae lock o' his gowden hair

We'll theek our nest when it grows bare.

'Mony a one for him maks mane,

But nane sall ken whar he is gane:

O'er his white banes, when they are bare,

The wind sall blaw for evermair.'

Vocabulary help: Corbies - ravens. Fail - turf. Hause - neck. Theek - thatch.

a. Listen to the ballad, which is often performed as a song, in renditions by Hamish Imlach and Steeleye Span.

3. Christine De Luca, ‘Hentilagets’ / ‘Odds and ends’ (2014)

This is a poem composed after studying Verbiest’s Chinese map of the world (1674), which puts China at the centre of the world. Having seen the map on display in the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow University, Christine De Luca writes in Shetlandic, and translates into English, her poem about the residual strengths and potential of the Shetland islanders whose archipelago map-makers still often enclose in a box in the corner of a map of Britain.

a. Study the map then read the poem first in Scots and then in its English version.

Hentilagets*

No dat I’d lippen dee, Verbiest, sae trang wi

da Chinese Emperor, ta ken aboot dis hentilagets

o skerries. Or, for dat maitter, wi der namin.

Even da best map-makkers missed wis oot or,

whan dey fan wis, prammed wis ida Moray Firt

ithin a peerie box. Maistlins we wir jöst owre

da horizon, a vague prospect, Ultima Thule.

I canna blame dem, for dat nordern ocean

stipplt apö first maps wis buskit wi wrecks

an sea munsters; hed da likkly o a graveyard.

Hendrik Hondius man a read da starns wi

a Davis quadrant an checkit better charts,

Mercator’s, afore he teckled terra incognito,

dat Orcades and Schetlandia Blaeu engraved.

An sae da box appeared: tree dimensions flatcht

ta twa; latitude an longitude forgien;

laand scaled doon, crubbit up, sae da rest could braethe.

But tap dat box an, boy, we’ll loup oot! Gie you

sic a gluff, you’ll nivver trust a Verbiest again!

We’ll rex wis, i wir ain place, prood an prunk

boannie as a weel-med gansey, newly dressed.*

*Hentilagets are tufts of sheep’s wool often caught in heather; usually the softest.

*Dressing a newly knitted garment involves washing and stretching.

Translation:

Odds and ends

Not that I’d expect you, Verbiest, so busy with

the Chinese Emperor, to know about these oddments

of skerries. Or, for that matter, with their naming.

Even the best map-makers missed us out or,

when they found us, crammed us into the Moray Firth

in a little box. Mostly we were just over

the horizon, a vague prospect, Ultima Thule.

I cannot blame them, for that northern ocean

stippled on to first maps was decorated with wrecks

and sea monsters; had the appearance of a graveyard.

Hendrik Hondius must have read the stars with

a Davis quadrant and checked better charts,

Mercator’s, before he tackled terra incognito,

that Orcades and Schetlandia Blaeu engraved.

And so the box appeared: three dimensions flattened

into two; latitude and longitude compromised;

land scaled down, confined, so the rest could breathe.

But tap that box and, boy, we’ll leap out! Give you

such a fright, you’ll never trust a Verbiest again!

We’ll stretch out, in our own place, visible and confident,

beautiful as a well-made jumper, newly finished.

b. Now listen to Christine De Luca introducing and reading her poem. Then read it out recording yourself.

Transcript

Listen

Hentilagets*

No dat I’d lippen dee, Verbiest, sae trang wi

da Chinese Emperor, ta ken aboot dis hentilagets

o skerries. Or, for dat maitter, wi der namin.

Even da best map-makkers missed wis oot or,

whan dey fan wis, prammed wis ida Moray Firt

ithin a peerie box. Maistlins we wir jöst owre

da horizon, a vague prospect, Ultima Thule.

I canna blame dem, for dat nordern ocean

stipplt apö first maps wis buskit wi wrecks

an sea munsters; hed da likkly o a graveyard.

Hendrik Hondius man a read da starns wi

a Davis quadrant an checkit better charts,

Mercator’s, afore he teckled terra incognito,

dat Orcades and Schetlandia Blaeu engraved.

An sae da box appeared: tree dimensions flatcht

ta twa; latitude an longitude forgien;

laand scaled doon, crubbit up, sae da rest could braethe.

But tap dat box an, boy, we’ll loup oot! Gie you

sic a gluff, you’ll nivver trust a Verbiest again!

We’ll rex wis, i wir ain place, prood an prunk

boannie as a weel-med gansey, newly dressed.*

Model

Hentilagets*

No dat I’d lippen dee, Verbiest, sae trang wi

da Chinese Emperor, ta ken aboot dis hentilagets

o skerries. Or, for dat maitter, wi der namin.

Even da best map-makkers missed wis oot or,

whan dey fan wis, prammed wis ida Moray Firt

ithin a peerie box. Maistlins we wir jöst owre

da horizon, a vague prospect, Ultima Thule.

I canna blame dem, for dat nordern ocean

stipplt apö first maps wis buskit wi wrecks

an sea munsters; hed da likkly o a graveyard.

Hendrik Hondius man a read da starns wi

a Davis quadrant an checkit better charts,

Mercator’s, afore he teckled terra incognito,

dat Orcades and Schetlandia Blaeu engraved.

An sae da box appeared: tree dimensions flatcht

ta twa; latitude an longitude forgien;

laand scaled doon, crubbit up, sae da rest could braethe.

But tap dat box an, boy, we’ll loup oot! Gie you

sic a gluff, you’ll nivver trust a Verbiest again!

We’ll rex wis, i wir ain place, prood an prunk

boannie as a weel-med gansey, newly dressed.*

18.3 Distinctive characteristics and Scots as a language for poetry

When asked what he thought Robert Burns’ best single line of poetry was, Hugh MacDiarmid said that it was the line, ‘Ye are na Mary Morrison…’ from the song, ‘Mary Morrison’. In context, the meaning is simple enough: the speaker, a young man at a dance, is looking around for the woman he has set his heart on and doesn’t see her. The women he sees are fine and good but none of them are Mary Morrison.

Norman MacCaig said he thought MacDiarmid’s choice was surprising, since he’d expected MacDiarmid to quote a politically charged line, such as ‘A man’s a man for a’ that…’ But MacDiarmid’s choice was deeply political in one important sense. He wrote elsewhere that he was committed to bringing to an end the idea of ‘superiority’ attached to one language and imposed over and above another. He was thinking not only of Scots and Gaelic but all the languages of the world which had been threatened, and some made extinct, by colonial conquest. He wrote: ‘All dreams of imperialism must be exorcised, including linguistic imperialism / Which sums up all the rest.’ (MacDiarmid, H. 1955.)

In this light, his preference for that line of Burns takes on a powerful significance, because there is all the difference in the world between saying ‘You are not Mary Morrison’ and ‘Ye are na Mary Morrison.’ Those two tiny, seemingly unimportant words ‘Ye’ and ‘na’ set the tone for the whole line; they combine regret, haunted urgency in the search for the beloved, loss and regret at not seeing her or finding her there, and a definite, optimistic sense of preference: other young women may indeed be fine, attractive, bright in various ways and beautiful to the eyes of various beholders, but none of them is the woman for him.

It’s in that vernacular, colloquial, intimate yet objective tone that the poetry of the line resides.

Burns (1759–96) wrote his poems and songs in the culmination of the work of a number of writers which opened the ground for him, both in terms of a reading public in Edinburgh, who were well-educated in Scottish poetic tradition and eager for new work, and in terms of a broader public keenness for engagement with Scots vernacular poetry, first in Burns’ native Ayrshire, then further afield.

The key figure in this story is Allan Ramsay (1686–1758), whose two-volume anthology The Ever Green (1724) drew upon the Bannatyne Manuscript of poems from the 15th and 16th centuries collected by George Bannatyne in the 16th century. When Ramsay published his anthology in the 18th century, it reintroduced poets such as Dunbar and Henryson to a new readership.

The immediate successor in this story is Robert Fergusson (1750–74), whom Burns described as his ‘elder brother in misfortune, by far my elder brother in the Muse’: that is, Burns recognised that Fergusson, in his poverty and ultimate breakdown and incarceration in an asylum for the insane, was in more desperate conditions than himself but that nonetheless, he was as great or even a greater poet. Certainly, Burns gained from the writing and cultural presence these two predecessors had made.

In the 19th century, poetry in Scots was sometimes found in the newspapers and periodicals of the cities, particularly Glasgow and Aberdeen. Tom Leonard’s anthology Radical Renfrew collects many of these poems of protest, demanding social redress. As the majority of the population of Scotland centred in the cities (especially industrial Glasgow) the vernacular speech idioms and literary forms that had been familiar and fluent in village politics and rural life were applied in city contexts. Important poets of this era included David Webster (1787–1837), Thomas Burnside (1822–79), and John Barr (1822–92) and Jessie Russell (1850–1923) both of whom emigrated to New Zealand.

After the First World War, the Scottish Literary Renaissance led by Hugh MacDiarmid foregrounded poetry in Scots, with the long, book-length poem ‘A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle’ (1926) galvanising the literary scene in its radical engagement with adult themes and ideas that most nineteenth-century Scots language poetry had been neglecting.

MacDiarmid took on an international range of reference in the priorities of politics and the economy described by Marx, ideas of psychology and sexuality explored by Freud, concepts of power and the refusal of a ‘slave-mentality’ affirmed by Nietzsche. In this, he had much in common with his contemporaries, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, but he delivered his most searching expositions of these ideas in poems written in vernacular Scots.

MacDiarmid’s younger Scottish contemporary, William Soutar (1898–1946), was equally dedicated to writing poems in Scots, both poems for adults such as MacDiarmid had pioneered, and brilliantly written poems for children, ‘Bairnrhymes’, riddles and ‘Whigmaleeries’.

These poets regenerated Scots poetry in the 18th, and then again emphatically in the 20th century. The extent to which Scots is available to anyone in the 21st century through online sources as well as freely accessible archives means that the rich history of the subject can be more fully explored than ever before. At the same time, it will always be necessary to enhance and complement our study of the subject by experiencing Scots as a living language, which means venturing into the world beyond libraries and universities.

Having acquired some knowledge and experience of how Scots is spoken currently, it is equally necessary to return to our opening point, that words, language, forms of expression are different in poems than they are in everyday speech. This unit has done no more than introduce some of the range of different poetic forms and moments of urgency through history in which they have found expression.

Activity 8

In the penultimate activity of this unit, you will note your views on one of the aspects you have come across here: The distinctive or ‘untranslatable’ characteristics of poetry in Scots.

- Go through the work you have done in this unit again and think about the poem that has captured you most of all, especially in terms of:

- a. the way in which the Scots language was used to make an impression on you as a reader/listener. Think also of reasons for your choice.

- b. whether you think the message of the poem could not have been the same had it been written in English or Standard Scottish English – linking to the idea of distinctive or ‘untranslatable’ characteristics of poetry in Scots.

- c. your favourite line/phrase/word(s) used in the poem.

- d. maybe also the link between language and the theme of the poem.

- Then write a short paragraph expressing your thoughts on the points listed above. You may even want to write this short paragraph in Scots. Below is some guidance on how to approach this, especially if you are not a Scots speaker.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer will be different.

The poem that moved me most was Gerda Stevenson’s ‘The Abdication of Mary Queen of Scots’. I was struck be the power of emotion here, by how Mary was presented as a strong woman, even in her weakest hour. Had the poem been written in English, this compelling message would have been significantly weakened. The Scots language gives Mary authenticity, it is at the heart of her sense of identity. Scots is the most appropriate ‘tool’ to express her powerful emotions.

My favourite lines are the ones reflecting her anger, deep sadness and the power she still holds through not submitting her mind to her abductors are:

O, I could run rings roon ilka yin o ye in Greek an aa,

as weel’s ma bonnie French, but ye’re naethin, naethin noo,

juist ghaists

Scots language is closely related to the theme of the poem, power. This happens in two ways, Scots is used as the language of the oppressed, those not in power, but also as the language of people with a strong sense of identity who resist the power of the establishment

Writing in Scots

You have now come across a wide range of texts in different regional variations of Scots and have:

- become acquainted with the way in which the language is ‘put together’ into sentences and texts.

- also studied key grammatical features of Scots, which are tools for forming longer utterances in the language.

- throughout this course assembled your own record of Scots vocabulary, ideally noting examples of how the words you listed are used in context.

These three aspects will now help you put together your own written Scots. Instead of writing in English and then translating into Scots, we suggest you start writing in Scots straightaway.

If you are new to the language, start small, even with just bullet points. Then go back to texts in Scots you have read in the course and explore how writers have used words and phrases to link shorter bits of sentences to create longer and more complex ones.

Then, step by step, you are on your way to produce your own written Scots – and do not worry about mixing words from different Scots dialects. Remember that you have learned that Scots is a living language that is shaped by its users who pick and choose their own repertoire of vocabulary.

18.4 What I have learned

Activity 9

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning points of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- the range of vernacular dialects and the synthesis of dialects in crafted, literary Scots poems

- the range of forms in literary Scots poems and the relation between voice (or voices) and poetic form (or forms) through history

- ways of saying (forms of address: who is being talked to, what is the position of the reader and what is the position of the writer?)

- the distinctive or ‘untranslatable’ characteristics of poetry in Scots.

Further research

You can explore further works by the poets you have encountered in this course and discover more poems in Scots on the Scottish Poetry Library website.

Rampant Scotland features an interesting selection of Scottish poetry.

Read a dialogue about Haldane’s Da Blyde-Meat between Alan Riach and writer Morag MacInnes on the Writing the North website.

Find out more about Christine de Luca and her work.

Listen to Christine De Luca talking about writing poems in Shetlandic and in English, how the language of her childhood home in Shetland shaped her and the poetry she writes. She also reads some of her poetry in this videoVideo player: WIKITONGUES-_Christine_speaking_Shetlandic.webm.480p.vp9.webm .

Read more about Hugh MacDiarmid’s work and views in this chapter by Alan Riach (2011) ‘The Violence and Virtues of Nations’ in Gardiner M. et al. Scottish Literature and Postcolonial Literature: Comparative Texts and Critical Perspectives, Edinburgh University Press, ProQuest Ebook Central.

Listen to Hugh MacDiarmid reading ‘A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle.

Read and listen to William Soutar’s poetry for children on the William Soutar website (which includes sound recordings and films).

Now go on to Unit 19: Literature – prose.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Robert Garioch Sutherland plaque: gnomonic - https://www.flickr.com/photos/28120556@N08/8361785388 - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Edwin Morgan: Alex Boyd. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/91/Edwin_Morgan_by_Alex_Boyd.jpg. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Fist Sunday Ferry Protest: Giorgio Galeotti - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_Sunday_Ferry_Protest_-_From_Uig_(Isle_of_Skye)_to_Lochmaddy_(North_Uist),_Scotland,_UK_-_May_21,_1989_04.jpg - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Photograph of Gerda Stevenson: Gerda Stevenson

De Luca, C. (2014) ‘Hentilagets/Odds and ends’ Christine De Luca

Painting of Robert Fergusson: Robert Fergusson, 1750 - 1774. Poet. Photography by Antonia Reeve. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/2421/robert-fergusson-1750-1774-poet-about-1772. National Galleries of Scotland.