Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 3 February 2026, 10:23 PM

Unit 19: Literature – prose

Introduction

In this unit, you will learn about prose in the Scots language. There are innumerable documents in Scots dealing with matters of court, law, diplomacy and (in modern times, what we would call) cultural criticism. Since this unit deals with literary prose, you will focus on prose fiction, both short stories and novels. Prose fiction has been written in Scots for centuries but the most crucial era for this literature is in that period where oral culture, and written, print-generated culture, overlap. It is tempting to think that one superseded the other, but this is simply not true. Everyone tells stories verbally, even today.

The art of storytelling comes from ancient times and precedes writing, but when song- and story-collectors began their work seriously and transformed their collected material into written and then printed work, they co-existed with prose-fiction, continuing in the oral tradition, as you have learned in unit 13. One of the great twentieth-century collectors, Hamish Henderson, referred to this as ‘the carrying stream’ and it complements our sense of written prose in Scots. The historical significance of this period, mainly from the 18th into the 19th centuries and continuing, is that at its start, it coincided with the English language claiming an increasing authority in the context of the British Empire. Scots as a written and printed language was eclipsed in some crucial respects by English. It wasn’t superseded or killed off, instead Scots speech maintained a vital currency of communication even while the English language took the central position of authority in the narrative prose of most published works.

You are going to study two crucial examples that seem to run counter to this general truth: Walter Scott’s Wandering Willie’s Tale and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Thrawn Janet. Then you are going to consider the major breakthrough made by Lewis Grassic Gibbon in the 1930s in his trilogy of novels collected as A Scots Quair: Sunset Song, Cloud Howe and Grey Granite. You are going to weigh the counter-arguments for writing in English and Scots proposed by Edwin Muir and Hugh MacDiarmid in their confrontation in 1936 and its consequence in 1940. Then finally, you will look at the situation as it has developed since the 1980s to the 21st century. There are four aspects you will explore closely as listed below.

Important details to take notes on throughout this unit:

- the narrator and the narrative: who utters the words in the Scots language and what is the authority of her or his narrative

- the the relation between storytelling/the short story and the novel as forms of prose literary fiction

- the relation between English and Scots in literary prose fiction and how has it changed from the 18th century till now

- changes in the 1930s and the lasting effect these have had on literary prose fiction since then.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

19. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: a set of twenty-four sheets of writing paper (Sc. 1818 Sawers). Comb. quair-book, a book consisting of a single quire of paper so folded as to make 16 pages, a kind of exercise book

Example sentence: “Afore Agyness Deyn, Scotland saa Vivien Heilbon play Chris Guthrie oan the telly in aa three books o Gibbon’s A Scots Quair”

English translation: “Before Agyness Deyn, Scotland saw Vivien Heilbon play Chris Guthrie on the TV in all three books of Gibbon’s A Scots Quair.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Afore Agyness Deyn, Scotland saa Vivien Heilbon play Chris Guthrie oan the telly in aa three books o Gibbon’s A Scots Quair

Model

Afore Agyness Deyn, Scotland saa Vivien Heilbon play Chris Guthrie oan the telly in aa three books o Gibbon’s A Scots Quair

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

Language Links

The word ‘quair’ is a Scots term for a book, literally, a ‘quire’ (that is, 24 sheets of writing paper folded to make 16 pages). The dictionary link to the word notes its use in the 18th century as well as its further meaning – more generally as a literally work, as in the much older poem by James I, The Kingis Quair (c.1423). Dictionary definitions can give you documented historical references, but since this section is about literature, allow the powers of implication to hold sway for a moment and think of the significance Lewis Grassic Gibbon gives in his work to the voices of women and men – in their daily practice, in gossip, raised in song or whispered in terms of endearment, expletive in anger, joined in concurrence of ideals, isolated and lonely in their exclusion from the normative pressures of conservative society...

Is it possible that he chose the word as the title for the trilogy partly at least for its resonance with the word, ‘choir’? I don’t mean to challenge etymological accuracy here, only to suggest that a bound number of sheets of paper on which are written or printed words representing speech might be thought of as a choir of human voices rather than only as a collection of signs made from wood and ink. Whatever the linguistic history, the idea is germane to Grassic Gibbon’s achievement, as you shall see.

Related word:

Definition: 3. Spirit, mettle, energy, drive, spunk, vigorous common sense and resourcefulness

Example sentence: “He’s no ill aff fir smeddum…”

English translation: “He’s not ill off for spirit…”

Activity 3

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

He’s no ill aff fir smeddum…

Model

He’s no ill aff fir smeddum…

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word

19.1 Examples of prose fiction written in Scots

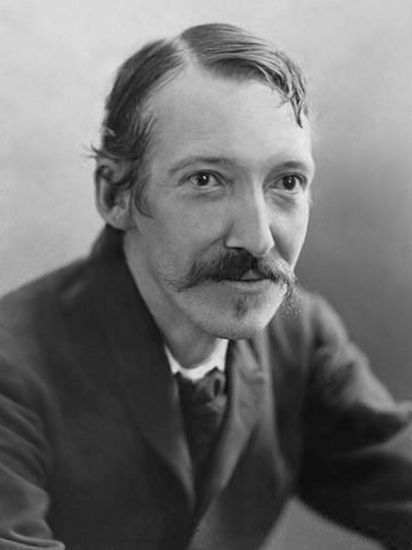

This section will focus on two stories, Walter Scott’s Wandering Willie’s Tale and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Thrawn Janet. The section will consider the ways in which Scots language is used in relation to English in the stories, how the stories themselves balance aspects of the supernatural and the material or earthly world. They will explore questions of who the narrator is and who the narrative is addressed to, and finally what legacy the stories imply for their own narrators and for subsequent readers. This last question prompts consideration of the relation between storytelling and extended prose fiction, novels.

The Scots language in these two stories is used to particular effect, not only to generate a quality of strangeness or mystery but also to give a sense of vocal immediacy or authenticity. This is a paradox: one aspect of its use as written, printed language exploits its unfamiliarity: to those accustomed to seeing the English language on the page, then Scots may seem odd or difficult; the other aspect exploits the colloquial intimacy of Scots language and implies that the speakers of these stories are talking ‘naturally’.

We know that all literature is artifice – all the arts employ design or intention, structure and method – but the relation between writing and speech is a palpable presence in these stories. How does this work? What effect does it have? You will answer these questions through exploring the two stories in some detail.

Activity 4

One of the most helpful essays on the art of storytelling and its distinction from the art of the novel is The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov (1936) by Walter Benjamin. You will read parts of this short essay in this activity, as it will form one of the cornerstones of this unit.

Read Benjamin’s essay, focusing mainly on sections I–V, and then match the beginnings of the sentences with the appropriate ending according to Benjamin’s text.

We have done the first example for you:

Mankind is losing… /… the ability to exchange experiences.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 7 items in each list.

…differs least from the speech of the many nameless storytellers.

…with the lore of the past, as it best reveals itself to natives of a place.

…contains, openly or covertly, something useful.

…is a symptom of the decline of storytelling.

…is its essential dependence on the printed book.

…and in turn makes it the experience of those who are listening to his tale.

…who is no longer able to express himself by giving examples of his most important concerns as he has not experienced these himself or heard from others who did.

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.The rise of the novel at the beginning of modern times…

b.The most effective stories combine the lore of faraway places, such as a much-traveled man brings home…

c.What distinguishes the novel from the story…

d.The novelist has isolated himself, a solitary individual…

e.The storyteller, a social being, takes what he tells from experience - his own or that reported by others...

f.The nature of every real story...

g.The great storytellers are those whose written version…

- 1 = g,

- 2 = b,

- 3 = f,

- 4 = a,

- 5 = c,

- 6 = e,

- 7 = d

Benjamin draws our attention to a number of things, which can illuminate our reading of Scott and Stevenson and how their Scots language stories work in these examples. I’d like to draw attention to two key comparisons he makes. One is between the storyteller who stays at home and knows all about a particular locality, its inhabitants and ways of life; the other is the storyteller who travels the world and visits other places, returning with news of foreign parts and different customs. What categories do the narrators of the Scott and Stevenson stories most closely fit? The second thing is the difference between the storyteller and the novelist.

In the oral tradition, the storyteller is always present, telling the story; in the printed tradition, the novelist is almost always absent (except, these days, at book festivals and signings). You will now investigate how this observation applies to the narrators in Scott’s and Stevenson’s stories.

Let’s start with the older text, Scott’s ‘Wandering Willie’s Tale’ from 1824, which forms chapter six of the novel Redgauntlet. It is worth thinking about the novel and the story’s place within it before looking at the story itself:

Scott's silence [towards publisher and friends] as to the novel he was actually composing -- a silence which verges on deliberate misdirection -- lends support to the widely held view that Redgauntlet is Scott's most deeply personal novel. It offers more parallels with Scott's own life story than any other Waverley Novel. In particular, it draws on Scott's training as a lawyer and preparation for the bar […], on the tour of the Lake District in 1797 when he met his wife […], and on a professional visit to Dumfries and Galloway in 1807. Many commentators have detected a self-portrait in the young lawyer Alan Fairford, and a depiction of Scott's own father in the sternly Presbyterian Saunders Fairford. Models for Alan's friend Darsie Latimer have been sought in Scott's fellow students William Clerk and Charles Kerr of Abbotrule.

The narrator of the story is a character in the novel. The Scots of his story is embedded within the English of the narrative as a whole. Earlier chapters of the novel take the form of letters between characters, mainly in English, and the overall narrative of the book – Scott’s voice, one might argue – is given in English. So while the authority of Wandering Willie’s Scots is undisputed while the story lasts, it passes away into the larger context. But this can be regarded as something of a paradox. The story has been anthologised and read, probably, by more people over centuries, than have read the novel as a whole. That Scots voice and language has a lasting hold on the imagination of readers in a way that the novel only partly offsets. It has its own authority despite its context.

Activity 5

Part 2

In the closing dialogue at the end of the story (the end of the novel’s chapter six), Willie tells his companion that “it is nae chancy thing to tak’a stranger traveller for a guide when you are in an uncouth land.” His companion, who is the main link to the novel’s main narrative, responds by saying that he should not have thought so, since the narrator’s grandfather’s adventure as recounted in the tale “was fortunate for himself, whom it saved from ruin and distress; and fortunate for his landlord.” And then Willie delivers the final revelation, the moral of the tale, which taints the ending of the story and suggests a world of unpredicted consequences. And this is the element Benjamin labelled the ‘nature of every real story […] something useful’ – a lesson to be learned.

Listen to the moral of Willie’s tale and read it out yourself. What do you think is the lesson of the tale?

Transcript

Listen

Aye, but they had baith to sup the sauce o’ ‘t sooner or later,’ said Wandering Willie; ‘what was fristed wasna forgiven. Sir John died before he was much over threescore; and it was just like of a moment’s illness. And for my gudesire, though he departed in fullness of life, yet there was my father, a yauld man of forty-five, fell down betwixt the stilts of his plow, and rase never again, and left nae bairn but me, a puir, sightless, fatherless, motherless creature, could neither work nor want. Things gaed weel aneugh at first; for Sir Regwald Redgauntlet, the only son of Sir John and the oye of auld Sir Robert, and, wae ’s me! The last of the honorable house, took the farm aff our hands, and brought me into his household to have care of me. My head never settled since I lost him; and if I say another word about it, deil a bar will I have the heart to play the night. Look out, my gentle chap,’ he resumed, in a different tone; ‘ye should see the lights at Brokenburn Glen by this time.

Model

Aye, but they had baith to sup the sauce o’ ‘t sooner or later,’ said Wandering Willie; ‘what was fristed wasna forgiven. Sir John died before he was much over threescore; and it was just like of a moment’s illness. And for my gudesire, though he departed in fullness of life, yet there was my father, a yauld man of forty-five, fell down betwixt the stilts of his plow, and rase never again, and left nae bairn but me, a puir, sightless, fatherless, motherless creature, could neither work nor want. Things gaed weel aneugh at first; for Sir Regwald Redgauntlet, the only son of Sir John and the oye of auld Sir Robert, and, wae ’s me! The last of the honorable house, took the farm aff our hands, and brought me into his household to have care of me. My head never settled since I lost him; and if I say another word about it, deil a bar will I have the heart to play the night. Look out, my gentle chap,’ he resumed, in a different tone; ‘ye should see the lights at Brokenburn Glen by this time.

Unlike Willie’s story, Stevenson’s Thrawn Janet (1881) was written as a complete work in itself, and published as soon as it was sent to the Cornhill Magazine after its completion. Stevenson begins the story in relatively straightforward English but moves into Scots very quickly and stays there. The Scots-speaking storyteller carries you through the tale and no return to an authoritative English language narrative comes at the end.

Activity 6

In this activity, you will establish to what effect and with what purpose the Scots language was used by Stevenson in this story.

Listen to the story read by the novelist, poet, playwright and performer Alan Bissett; or you can read the text of ‘Thrawn Janet’.

While reading/listening to the story, think about in what way Benjamin’s distinction between storyteller and novelist applies here. And what effect does the use of the Scots language have in terms of the authority of the narrator?

Answer

This is a model answer. Your notes might be different.

Walter Benjamin’s observation that one difference between (oral) stories and (printed) novels is that the storyteller is there in front of you all the time, while the novelist is hardly ever present. Here, Stevenson is playing on that truth: the storyteller in Thrawn Janet retains the narrative voice until the end, even though Stevenson, the author, has written and seen to that voice appearing in print for a wide readership. He’s playing with expectations that an omniscient narrator will return to vouchsafe good authority, and given that the subject of the narrative is what befalls a minister of the church, the implication is pretty clear that no such “grand narrator” is there at all.

All you have is the evidence of your eyes and experience to go on. Stevenson was writing at the other end of the 19th century from Scott. Darwin and Marx had made their intervention and Nietzsche and Freud were about to make theirs. Stevenson is more subtle than any of them but the implications of his work are as deep, and it’s through his use of Scots in this story that he presents them.

19.2 Lewis Grassic Gibbon and A Scots Quair

Activity 7

In this section you are going to consider the following aspects of the novel trilogy. While studying this section, take notes on the following questions:

- What is the most significant way in which the Scots language is used in Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s trilogy of novels, A Scots Quair?

- How does the language work in relation to the narrative?

- How does it work in relation to the voices of the characters and the voices of the people in the community?

- How does that community change from one novel to the next?

A Scots Quair is a trilogy consisting of three novels: Sunset Song (1932) – voted Scotland’s favourite novel in a Scottish Booktrust survey in 2005, Cloud Howe (1933), and Grey Granite (1934). The novels revolve around the life of Chris Guthrie, a woman from the north-east of Scotland, during the early 20th century. In the opening note to A Scots Quair, Grassic Gibbon says that he has included Scots words, phrases, and idioms of speech, into the narrative, which is mainly written in English.

So the predominant language is English, but the infiltration of these words and their placement in the rhythm, texture and narrative of the novels changes their idiom entirely into Scots. The particular effect this has on the narrative is to intertwine the words of the main characters, both their speech and their internal unspoken thoughts, with that of the observing eye; it also intertwines the language of the local people, both at their most idealistic and their most spiteful and gossipy.

Close reading shows how this works, even within a single sentence. In the opening paragraph of Part Two of Sunset Song, we visualise Chris Guthrie running up the hill, lying down, and breathing deep, but the words take us into her consciousness so that we think with her as well as observe her. Note that when Gibbon says she would turn back for nothing, “not even that whistle of father’s”, he does not write, ‘of her father’s’ (which would have maintained an external account, but the leaving out of the possessive pronoun suddenly creates a shift in narrative perspective and we see things from Chris’ point of view).

Gibbon’s novels take us from farm to small town to city, and the community and the language is different in each one. The language conveys aspects of decency, civility and hope, intimacy and affection, brutality and violence, but also becomes less easeful, more stressed, as the trilogy proceeds. It can be argued that this use of Scots voices contributes to the overall narrative structure. In the passage I’ve just referred to, at the beginning of Part Two, when Chris comes to the standing stones and lies down to gather her thoughts, she remembers the last time she was there, which we’ve just read about at the end of Part One.

The second section then recounts the events that have taken her from the end of Part One to the beginning of Part Two, which we will return to at the end of the unit. The effect of this narrative approach is a sense in the reader that the narrative cannot be predicted. What happens in consequence of our actions involves a multitude of choices and possibilities. Nothing is inevitable, and therefore the struggle is worthwhile because a better outcome might be made. By embedding the idiom of different Scots voices so deeply in the narrative, it might be argued that Gibbon is showing how there is always more than one perspective, more than one way of telling, and understanding, any story. This is a key element in modernist art and Scots prose fiction is a clear demonstration of how it works.

19.3 The predicament of the Scottish writer

Activity 8

In this section, you are going to consider the aspects listed in the questions below. While studying this section, take notes on these questions.

- What are the major points made by Edwin Muir in Scott and Scotland? Are they defensible?

- How did Hugh MacDiarmid respond to this in The Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry (1940)?

In the late 1930s, a series of books with the generic title The Voice of Scotland was initiated by Grassic Gibbon and Hugh MacDiarmid. Their intention was to invite a range of contemporary authors to write book-length essays on contentious themes and questions of the day.

Thus, Compton Mackenzie wrote Catholicism and Scotland, reminding predominantly Protestant readers that their greatest Scottish heroes, Wallace and Bruce, were pre-Reformation Catholics. Neil Gunn wrote Whisky and Scotland rehearsing all the ceremonies, rituals and traditions whisky-drinking once entailed, intrinsically celebrating sensitivity and care alongside carefully applied intoxication and language at play. Victor McClure wrote Scotland’s Inner Man about what good food and a healthy diet actually was and might again be in Scotland. Eric Linklater wrote The Lion and the Unicorn: what England has meant to Scotland and William Power wrote Literature and Oatmeal.

In the last in the series, Scott and Scotland: The Predicament of the Scottish Writer, Edwin Muir concluded that the only way to take Scottish literature forward was to write exclusively in English. Gaelic would not serve and Scots was inadequate: only English could address an international readership, as was evident in the literary triumphs of W.B. Yeats and James Joyce.

Not only MacDiarmid, whose Scots-language poetry had been so revolutionary in the 1920s, but also the composer F.G. Scott, were furious. Scott’s brilliant settings of MacDiarmid, Burns, William Soutar, George Campbell Hay and others, encapsulated a Scots musical idiom in compositions self-consciously drawing on modernist innovations from Schoenberg, Satie and Stravinsky, while keeping the traditional sense of Scots song in play. Scott met Edwin Muir and his wife Willa and wrote of their meeting, “I had a long and very exciting talk with the pair of them, told them that I disagreed with everything in the book.” He argued definitively that there were poems in Scots (not least those of Burns) that were by any standards ‘major’. Edwin, Scott reported, could not contradict him. Willa “turned extremely grave and silent”.

In the long run, Muir had a point: Yeats and Joyce have an international cachet still not fully extended to MacDiarmid, Soutar or Grassic Gibbon, and there are still many folk unwilling to recognise Scots as a language no less valid than English. Yet MacDiarmid and F.G. Scott won the argument. One response to this argument was MacDiarmid’s editing of an anthology entitled The Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry, which for the first time emphasised Gaelic and Latin language traditions as well as those of Scots and English, in Scottish literature.

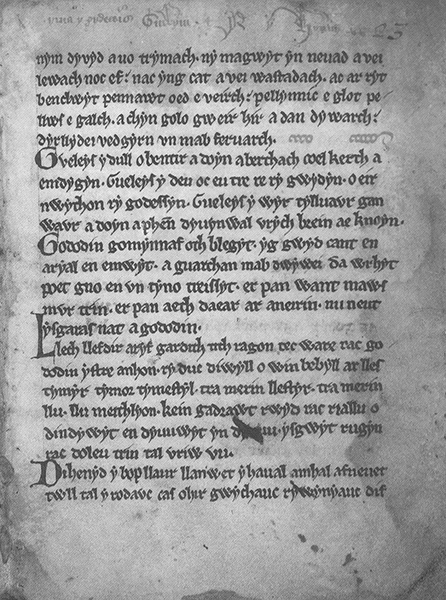

There is also important poetry in French (by Mary Queen of Scots, for example) and the first poem we might identify as Scottish, The Gododdin, was written in what we call Old Welsh or Cymric. In the 21st century, the understanding that multilingualism, a plurality of languages, is characteristic of Scottish literature in a way that distinguishes it from the more familiar ‘one nation, one language’ imperial ideal, is generally acknowledged, and open. The linguistic diversity of contemporary Scottish writing is proof, and one might consider examples from James Kelman’s Booker-prizewinning novel How Late It was, How Late (1994) and Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting (1996).

In this context, it is beneficial to recall how inflammatory the questions raised here may be. In the New York Times (29 November 1994), Sarah Lyall reported:

No sooner had James Kelman's novel How Late It Was, How Late won this year's Booker Prize for fiction than a full-scale furor erupted. One of the judges, Rabbi Julia Neuberger, declared that the book was unreadably bad and said that the awarding of the prize, Britain's most important, was a “disgrace.” Simon Jenkins, a conservative columnist for The Times of London, called the award “literary vandalism.” Several other critics sniped that the book should have been disqualified because of its heavy use of profanity.

Meanwhile, the British literary establishment huddled together defensively as Mr. Kelman appeared in a business suit at the black-tie Booker affair and, in his heavy Scottish accent, made a rousing case for the culture and language of “indigenous” people outside of London. “A fine line can exist between elitism and racism,” he said. “On matters concerning language and culture, the distinction can sometimes cease to exist altogether.”

This recalls Mark Twain’s ‘Explanatory’ note at the beginning of Huckleberry Finn (1884):

In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods Southwestern dialect; the ordinary ‘Pike County’ dialect; and four modified varieties of this last. The shadings have not been done in a haphazard fashion, or by guesswork; but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech. I make this explanation for the reason that without it many readers would suppose that all these characters were trying to talk alike and not succeeding.

Twain’s ironic and bitter humour comes through especially in that last sentence. By emphasising the subtle and not-so-subtle differences in dialect and language forms and idioms, by drawing attention to their representation in his novel, Twain is also indicating a quality inherent in racist superiorism, the tendency to be disdainful of such matters from a position of power and contempt. That relationship of power, and the relationship between speech and writing, is at the heart of our enquiry into the Scots language in literary prose.

19.4 Literary prose fiction in Scots from 1900 to new millenium

In this this section, you are going to focus on the authority of the Scots language in prose fiction from the 19th until the 20th century. The important thing is to understand not only the arguments but to consider them in their historical context. For example: Scots was a language of formal occasion, political authority and serious social functions, yet it was always related to speech and could modulate tone, balancing irony and directness in particular ways. At different periods in history, Scots in literary prose was in contest with the authority of the English language but the contest has been resolved over the period of around 1936 to 1999 (How Late It Was).There is a distinctive tension between the use of the voice in Scots prose and its local provenance, and the use of ‘neutrality’ or ‘objectivity’, which purports to deliver an omniscient authority.

One of the most important books to present the hinterland of writing Scots prose fiction is William Donaldson’s Popular Literature in Victorian Scotland (1986). Donaldson draws attention to ‘a new professional type’ of writer such as William Alexander, who write for the popular local press, in his case in Aberdeenshire, extended prose fiction in a local dialect form of Scots.

William Alexander, who was one of the leading journalists in Victorian Scotland and

…politically, he was a radical, supporting land reform and the abolition of hereditary privileges. Alexander was a prolific novelist of wide thematic range and considerable variety of style, from austere realism at one end of the scale, to mellow social comedy at the other. His works were serialised in popular newspapers. He consciously avoided the book as a publication vehicle.

His work was published in the periodical press and collected in complete novels such as Johnny Gibb o Gushetneuk (1877).

Activity 9

In this activity you will work with an extract from the second chapter of Alexander’s Johnny Gibb o Gushetneuk.

Read the extract and analyse it closely for the way it slips between Standard English and Scots forms. Highlight the Scots language in the extract as you read. Then think about the purpose and effect of the slipping between the two languages.

Discussion

Note:

The use of Scots in this passage adds, as we have seen in many other examples in this unit, an element of authenticity and realism through by naming key elements of the custom using Scots terms. There is a clear distinction made between the Scots and the English in most cases, where the Scots words are even visibly separated from the English. The tone of speech idiom is consistently conversational but the way in which Scots is introduced – often in quotation marks – indicates its particular and different provenance. Alexander’s prose uses Scots confidently and with a sense of local authority yet it still maintains an apparently formal ‘objectivity’ in its deployment of English and the relation this sets up between English and Scots.

Compare this with MacDiarmid’s revitalisation of Scots in the 1920s partly for his own individual creative priorities, partly to counter the increasingly familiar use of Scots in popular media, music hall and film, especially widespread in the establishment propaganda. MacDiarmid, in his short story or prose sketch ‘The Waterside’, uses Scots throughout and slips quickly and with great fluency between thoughtful, more meditative reflections, and representations of fast, dramatic action. These are sometimes serious – the threat to the children on the broken bridge is real – but also, at the same time, sometimes wildly comic. The moment where a mother rescues one child then finding it is not hers, throws it back into the water, is both ferociously comic and terribly chilling, partly because it seems to represent natural and understandable human behaviour, even if that behaviour is in some respects reprehensible.

The use of Scots in his prose and discussed in his essays ‘A Theory of Scots Letters’ and ‘English Ascendancy in British Literature’ shows a development and resistance to what MacDiarmid calls ‘English Ascendancy’: in other words, the way in which, over time, English has come to seem the normative language in Britain, while other languages are neglected or suppressed. Seamus Heaney, when discussing MacDiarmid’s literary use of Scots, established:

“…a demonstrable link between MacDiarmid’s act of cultural resistance in the 1920s and the literary self-possession of writers such as Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead and James Kelman in the 1980s and 1990s. [For Heaney, MacDiarmid’s poetry] prepared the ground for a Scottish literature that would be self-critical and experimental in relation to its own inherited forms and idioms, but one that would also be stimulated by developments elsewhere in world literature”.

And we conclude with a statement by Margery Palmer McCulloch, who verifies that Heaney’s comment, quoted above, represents “a meaningful endorsement of the way in which the inter-war Scottish Renaissance attempt to change the direction of Scottish literary (and ultimately political) culture, with its strong emphasis on national identity as well as international relationships and influences, [which] has been able to modify itself over the decades to bring about the confident, diverse yet recognisably Scottish contribution to international writing we have today” (2012, p. 73).

19.5 What I have learned

Activity 10

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning point of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- the narrator and the narrative: who utters the words in the Scots language and what is the authority of her or his narrative

- the relation between the short story and the novel as forms of prose literary fiction

- the relation between English and Scots in literary prose fiction and how has it changed from the 18th century till now

- changes in the 1930s and the lasting effect these have had on literary prose fiction since then.

Further research

Here you can read Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s A Scots Quair trilogy.

Optional Activity

This is an activity in which you can explore Grassic Gibbon’s short story Smeddum. Although the text of Smeddum is currently unavailable online, it is available in many readily available publications, which you will be able to access through libraries or otherwise.

Read the Lewis Grassic Gibbon short story Smeddum and consider the following questions:

- Who demonstrates smeddum in the story and how?

- Is smeddum a redeeming quality or does it come with liabilities?

- What makes this story comic and what makes it profoundly serious?

- Aside from the narrative itself, the characters and unfolding of events, one of the key elements in this story is its use of Scots language words and phrases. How are they employed? Select a sample of them and discuss this question further.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your answer might be different.

The story centres on Meg Menzies and her family; and her role as the matriarch is the central example of a character with smeddum. By the end of the story, though, her daughter has proven that she has her own smeddum in different respects: a sustained self-determination of character, a commitment to trying things out and not settling for compromise, a reluctance to surrender her independence quickly or easily and a willingness to take risks and follow through the consequences.

Meg seems lacking in smeddum at first as she tolerates and fondly, if regretfully, indulges her man’s tendency to avoid work and enjoy alcohol but she demonstrates smeddum by working the farm after his death and as most of her children leave, each in turn with different promptings by Meg. It is a quality of strength but the story shows how it brings with it responsibilities: possession of smeddum means you’re better equipped to deal with such responsibilities but still they can be an unwelcome burden.

What makes the story so funny is the unexpected turns in the narrative and the merciless contempt Meg shows for conventional pieties. She opposes social hypocrisy not by talking about it but by living her life by her own priorities. The tragic and profoundly serious aspect of the story is that it is essentially about human potential wasted by social convention, priorities of class and a context of overwhelming conservatism.

Meg’s victory is worked into the structure of the story but there is no sense that anything has changed because of it – except for the lives of her daughter and her daughter’s man, who set off together with Meg’s blessing, as her other children watch in shock and, one might hope, in possible understanding that the rules they’ve lived by aren’t endorsed by their mother.

You can find a useful discussion and analysis of Benjamin’s essay in Angus’ blog Mostly About Stories in the entry from 4 March 2019, ‘The Storyteller by Walter Benjamin – Summary and Analysis’.

Read an article about Tessa Hadley, who found her own life story told in Grassic Gibbon’s A Scots Quair.

To find out more about Johnny Gibb, the main character in William Alexander’s novel and the use of Doric.

Read Hugh MacDiarmid’s essays on Scots as a literary language and political tool in his essays ‘A Theory of Scots Letters’ and ‘English Ascendancy in British Literature’. These essays may be found in Hugh MacDiarmid (1992) Selected Prose, edited by Alan Riach, Michigan, Carcanet.

Now go on to Unit 20: Standardisation of Scots.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Gibbon Plaque: Bill Harrison - https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1329312 - This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

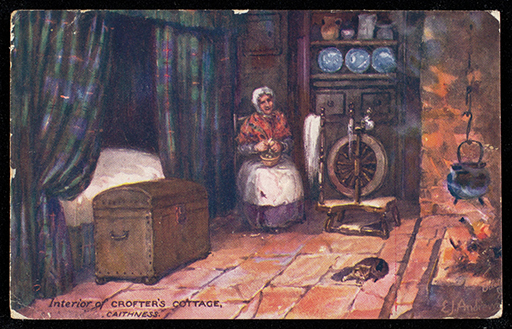

Postcard: Interior of Crofter's Cottage, Caithness (1900/1902) Leonard A. Lauder collection of Raphael Tuck & Sons postcards

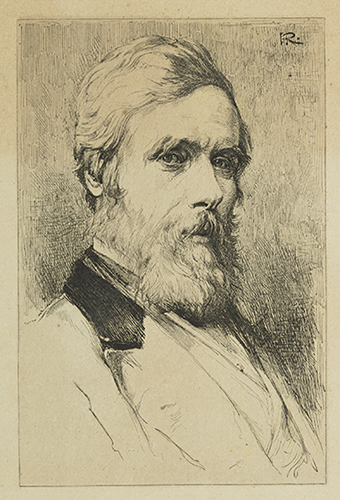

Portrait of Sir Walter Scott: © Hulton Archive/Stringer/Getty Images.

Extract ‘Scott's silence…’: Edinburgh University Library

Robert Louis Stevenson: State Library of New South Wales. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Lewis Grassic Gibbon: Photographer Unknown.

Francis George Scott: © The Estate of Lida Moser/National Galleries of Scotland

William Alexander: Frontispiece illustration for his novel 'Johnny Gibb of Gushetneuk'. Artist: Sir George Reid. National Galleries of Scotland

Extract ‘politically, he was a radical…’: Goodreads, https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/15487742.William_Alexander