Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 March 2026, 4:53 AM

Teamwork: an introduction for school governors

Introduction

School governors perform an essential role in the education system of Wales as part of a wider team working towards the same goal: ensuring that children in Wales are provided with an excellent education.

School governors, in effect, act as critical friends and partners to a school. Their wide-ranging work covers areas such as strategy, policy, budgeting, attainment, safeguarding, wellbeing and staffing. Although each governing body may differ, all governing bodies have set responsibilities and goals. Throughout this course, ‘school governor’ has been shortened to ‘governor’.

The powers and duties of the governing body include (Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government, 2013):

- providing a strategic view – setting the framework within which the head and staff run the school; setting the aims and objectives; agreeing policies, targets and priorities for achieving these objectives; monitoring and evaluating

- acting as a critical friend – providing support and challenge to the headteacher and staff, seeking information and clarification

- ensuring accountability – explaining the decisions and actions of the governing body to anyone who has a legitimate interest

There are many aspects to the role of governor, and all governors bring a wide range of existing skills, experience and knowledge to their role. The work of your governing body draws upon that wide range of skills and experiences. Schools and the education of children in Wales benefit greatly from the work of governors, who are, in effect, skilled and unpaid volunteers.

Governors work with each other, with school staff, parents and carers, pupils, the local community, the local authority, the regional consortia and the legislation that governs education within Wales. Teamwork therefore plays an important and essential role in developing and sustaining a successful governing body. This course provides an opportunity for you to reflect on your own team working experiences, to explore examples of team working in schools, and to reflect on leadership and the relevance of team working to your own governor experience.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

explain the role of teams in an educational context

understand the importance of working in ‘partnership’ with others in an educational context

apply the knowledge you gain to your role and work as a governor.

1 Governing bodies and ‘team working’

This section of the course explores the term ‘team working’ and is an opportunity for you to reflect on your own experiences of team working.

A great deal has been written about teams and groups: what the difference is between them and how they effectively operate. For the purposes of this course, we use the definition that a team is a group that ‘unites the members towards mutually-held objectives’ (Bennett, 1994).

Team working occurs in many different settings and in different areas of our lives. We may work in a team every day, or as a one-off event. Examples of team working range from planning a holiday with family or friends, planning an event with colleagues at work, responding to an emergency, working together to set a budget, participating in a meeting, to delivering a change in local or national government policy.

Mark Gardner of the National Governors Association identified that ‘building a successful governing body, like any other team, is about achieving balance and diversity in skills and experience. The governors also need to work together as part of a team’ (Young-Powell, 2016).

1.1 Working in a team as a governor

Governing bodies consist of individual governors who draw upon their own knowledge, experience and motivations. Governors are drawn from different organisations and may have been elected to the governing body or appointed. Within the governing body there is also a subset of teams created for particular purposes: these could be statutory committees, or committees that meet the particular needs of an individual school. Governing body committees can cover areas such personnel and finance, attainment, admissions, wellbeing and welfare, site, curriculum, or strategy.

Activity 1 asks you to think about the attributes and actions expected of school governors and what these may have in common.

Activity 1: Governors and team working

Look at the list below. Which attributes and actions would be expected of you as a governor? Can you identify a common theme in the attributes and actions you have chosen?

Comment

The statements are adapted from A Handbook for Governors of Schools in Wales (Governors Cymru Services, 2018) and form part of the Principles of Conduct for Governors in Schools in Wales. More information can be found on the Governors Cymru Services website.

Each statement is applicable to the role of a governor, and illustrates that, as a governor, team working plays an important role in your work. You make your contribution by working with other governors, staff, parents and carers, and pupils. This is done by:

- setting the aims and objectives for the school

- agreeing policies, targets and priorities for achieving these objectives

- carrying out monitoring and evaluating to see whether those aims, objectives and priorities are being achieved.

Each governing body will carry out its role in a manner best suited to the needs of the individual school and its pupils. However, governing bodies share some things in common, such as:

- the need to create statutory committees and statutory policies

- legal responsibilities

- appointing a clerk to the governing body

- taking advice from the Headteacher before making decisions.

Your work as a governor is generally undertaken in teams and in working with others. Although some of the statements above related to you as an individual, in order to achieve them you need to work with others.

Before moving onto the next section, which considers team roles, take a few moments to reflect on the governing body you are a member of.

Activity 2: Your governing body

Take a few moments to reflect on the governing body you are a member of and consider the following questions:

- What structure has the governing body adopted?

- What committees am I involved with?

- What is the remit of those committees?

- What training have I attended and with whom?

- What ‘type’ of governor am I?

- Examples include parent governor, teacher governor, staff governor, LA governor, headteacher as a governor, community governor, additional community governor, representative governor, foundation governor, associate pupil governor, partnership governor or sponsor governor.

Record your thoughts in a blog on the course website.

All of the blogs on this course are publicly viewable. You can decide whether you want other learners to comment on your blogs.

Comment

Each governing body has a structure that reflects the needs to the school community it represents. There are, however, some statutory requirements that governing bodies must meet, both in terms of committees and policies, including:

- a staff disciplinary and dismissal committee

- a staff disciplinary and dismissal appeals committee

- a pupil discipline and exclusions committee

- a Headteacher and Deputy Head selection panel

- Headteacher Performance Management Appraisers and Appeal Appraiser(s)

- pay review and pay review appeals

- grievance and grievance appeals

- capability and capability appeals

- complaints procedures.

Each governing body committee will have a reference document setting out its powers and duties, its place in the reporting structure, minimum number of governors. This must be reviewed annually.

More information on these can be found in the Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government guidance on induction training and school governance.

Having reflected on your own governing body and your work as a governor, the next section considers team roles.

1.2 Team roles

This section provides some background on team roles. As you work through it, think about the work you undertake in teams and the work you have undertaken with others, whether on a governing body or elsewhere.

The most quoted work on teamwork is Belbin’s research (1981). Whilst this has been developed and refined over the years, it still forms the basis of research and writing about teamwork. Belbin identifies nine clusters of behaviours, or roles, in a team. He suggests that individuals are more effective if they are allowed to play the roles they are most skilled in or most inclined to play, although they can adopt roles other than their preferred ones if necessary.

Each of the nine roles has both positive and negative aspects. Click on each one for more details:

Teamworking is not always easy, but it has a number of benefits. It provides a structure and means of bringing together people who have a mix of skills and knowledge. It also encourages the exchange of ideas, creativity, motivation and scrutiny, and can help to improve quality, attainment and the school experience. You should now attempt Activity 3.

Activity 3: Reflecting on team roles

Having learnt about the range of team roles that exist, take a few moments to reflect on the contributions you make to your governing body and other teams you form a part of. Which of the nine roles discussed above do you prefer to adopt? Do you take on different roles depending on the team you are working in?

Comment

There is no single answer to this activity: its purpose is to help you consolidate your thinking about your contributions to teams, and in particular the governing body you are a member of. You may have drawn on several of the team roles outlined by Belbin, or you may have found that one role in particular stood out. Thinking about past experiences and contributions can inform your present and future behaviour. By understanding your own preferences, you can build and develop your contributions to the work of the governing body, its committees and work with staff, parents, carers and the wider community. Being able to work with others in a team so that the right things are achieved is an important skill.

As a governor you attend meetings, committees and, perhaps, participate in small working parties. You may also visit the school to gain first-hand evidence of the quality of teaching and learning, or the conduct of pupils. You may have to present information to parents and carers, or participate in a school inspection and then draw up an action plan in response to the inspection report. All of these tasks are undertaken by working with others.

In this section of the course you have learnt that in undertaking your voluntary work as a governor, you form part of a team of governors. The governing body team is more effective when it works to make the best use of the skills, experiences and talents of its individual governors and draws upon each of their strengths. By understanding your own strengths and weaknesses as a team member, you can make a more effective contribution.

However, when individuals come together to work in a team, some form of leadership is required. A team needs facilitation and oversight, and, on occasions, a way of managing differing opinions. This is where the role of Chair of Governors is beneficial. Leadership is discussed further in Section 4.

Section 2 explores an important example of team working in schools in more depth: the concept of ‘partnership’ working with parents and carers. Understanding how and why schools work with parents and carers helps you to develop your expertise as a governor and enables you to reflect on the many differing types of teams found in your school community.

2 A ‘partnership with parents and carers’?

Parents and carers play an important role in a child’s education. Schools work closely with parents and carers in relation to the wellbeing, development and education of all children who attend their school. The phrase ‘partnership with parents and carers’ has been developed to reflect that close relationship and the contribution that each makes to a child’s development and education. The partnership is of particular importance in early years settings.

But what is a partnership? The term is in common everyday use. At its simplest, a partnership is an association of two or more people (or organisations) working together towards a common goal. Those goals may be long or short term. In effect, a partnership is a team, as defined in Section 1.

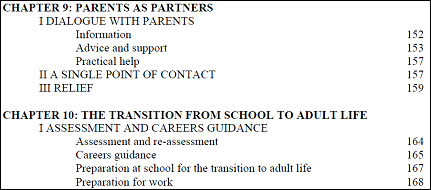

In education, the idea of a partnership between parents or carers and practitioners (used here to refer to those employed as teaching staff in the school) has been around for many years. In the late 1970s, the Warnock Report reviewed provision for children with special educational needs in England and Wales. The report contained an influential chapter entitled ‘Parents as partners’ (CEEHCYP, 1978).

Considerable evidence has been gathered from academic studies and observations of the value of such a partnership. However, it is not a straightforward notion: challenges can arise when practitioners and parents or carers endeavour to work closely together to benefit a child’s wellbeing, development and learning. In particular, some parents and carers may be tentative about becoming partners; others may have had both positive and negative experiences of the school environment.

2.1 Thinking about ‘working in partnership’

Open and inclusive approaches to partnership working have led to widespread recognition of the importance of parents and carers as partners - particularly during children’s earliest years, when care and education are closely linked. Parental and carer participation has also been enabled by specific educational legislation that gives parents and carers a greater voice as ‘consumers’ of a public service.

Working on an equal footing with parents and carers is important, as is the understanding that neither a practitioner nor the parent/carer is seen as ‘knowing best’. Each has a distinctive perspective on a child that complements the other. Working together as a team to support a child’s development and education opportunities maximises that child’s chance to achieve their potential.

Activity 4: Words and concepts associated with the idea of a ‘parent/carer partnership’

Think about each of the following words and identify those you would associate with a practitioner and parent/carer partnership. Then, in the blog, record the words you identified. For each word identified provide a short explanation for your choice.

- Involvement

- Support

- Collaboration

- Engagement

- Consultation

- Shared understanding

- Respect

- Discussion

- Knowledge

- Experience

Comment

All the words are relevant in some way. The partnership does not remain static and takes different forms as a child progresses through their development and education. In early years, the partnership draws widely upon a shared understanding and discussion; later on, it often evolves into a more identifiable set of roles and responsibilities.

Parents, carers and practitioners view partnership in different ways, and how a partnership is made workable varies considerably: what is appropriate in one area may not be considered suitable in another, and innovative practice in one setting may be commonplace elsewhere.

Given that practitioners usually initiate the partnership, they often take the lead in defining its nature and deciding the extent to which parents and carers enter the professional educational domain. Practitioners often assume that they know what is in the best interests of parents and carers (Bastiani and Wolfendale, 1996; Edwards, 2002), which can result in a partnership that is one-sided.

The educational environment and legislation that schools operate in often changes. Change is relevant because it often involves both practitioners and parents/carers. Change also has an impact upon the partnership and the wider school community. Over past decades, changes have included the requirement for practitioners to consult with parents and carers. There is now parental/carer representation at local authority and school governing body level. Steps are also taken to gather parents’ and carers’ opinions during school inspections.

The ‘Better Education for Children in Wales’ agenda has led to both major and routine government reviews designed to promote and achieve better educational experiences and educational achievement. In 2019 alone there were consultations on Our National Mission: A Transformational Curriculum, Keeping leaners safe guidance and Curriculum for Wales 2022 guidance. All those involved in a child’s development and education need to be aware of planned developments and changes. This is not always an easy task, but it’s one in which practitioners and governors can become involved, sharing these developments and impacts as part of their work and partnership with parents and carers. A knowledgeable, informed and engaged school community can support and enhance that change process.

2.2 Why work together?

There are many reasons why parents, carers, governors, practitioners and the school community should work together.

Educational researchers and practitioners often stress the benefits for children’s learning when practitioners, parents, carers and pupils work as an effective team. Parent-practitioner collaboration can be important to a child’s identity, self-esteem and psychological wellbeing. The close cooperation of parents, carers and practitioners in providing support to children is especially important during times of change and transition. This alone is a compelling reason for a close partnership.

The key adults in a child’s life should be able to relate to them and encourage them in similar ways. To get a sense of the extent to which parents and carers can be involved in children’s education, you will now explore how they:

- are educators

- give ‘background’ support to practitioners

- work alongside practitioners.

2.2.1 Parents and carers are educators

All parents and carers are active informal educators, whether or not they work in conjunction with a child’s professional educators, practitioners. Parents and carers support a child’s learning in all aspects of their lives, and children learn from participating in family and community life. This may include:

- observing and participating in preparing and sharing meals

- being involved in the care of other family members (siblings, grandparents)

- participating in shopping and errands

- experiencing family and community gatherings

- making journeys

- sharing books, stories, songs, videos, social media posts, films and dramas with parents, carers and siblings.

As a governor you may encounter a situation where a parent may want to take this further and extend their involvement by formally becoming ‘home educators’. This may be done because the parents or carers feel that their child is unhappy in a formal setting. They believe their child can thrive when educated at home. Those who choose to educate at home do however remain in a minority.

2.2.2 Parents and carers give ‘background’ support to practitioners

Many parents and carers take on an educating role by talking, playing, reading and singing with their children. For many parents and carers, their liaison with practitioners and other child-focused agencies forms only a part of the educational experience they seek to provide for their children.

Parents and carers are, in effect, a child’s first teachers – but not all parents and carers are able to become involved when a child goes into a school environment. Whilst many parents and carers will become involved in partnership working and their child’s education, there may also be reasons why a parent or carer is unable (or chooses) to not be involved. It is therefore important to be careful when drawing conclusions and consider the reasons why parents and carers may not appear to do what a setting asks of them, or not be fully involved in their child’s education.

The Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government has actively encouraged a ‘background’ parental and carers role at all stages of a child’s education. Ideas and information have been developed and made widely available: the ‘Education Begins at Home’ campaign, for example, had both a Twitter feed and a Facebook page to encourage parental and carer involvement.

Government-led initiatives are significant in helping parents and carers feel that they can be involved in their child’s formal learning. The resources provided also provide information, ideas and encouragement to enable parents and carers to be less dependent on early years and school settings.

You should now attempt Activity 5, which provides an opportunity to explore and reflect upon the role parents and carers have as ‘educators’.

Activity 5: Parents and carers as educators

Take a few moments to read an article by Owen Hathway (you will need to scroll down after clicking on the link) and then reflect on its relevance to you as a governor. You may choose to make a few notes of the key points made.

Comment

This activity is an opportunity for you to reflect on the role that a parent/carer plays in a child’s education. Owen Hathway is a policy officer and the article represents his views. His employer is the National Union of Teachers.

The author notes the need to involve parents, carers and the wider community to ensure that each child can achieve their full potential. This reflects the idea that ensuring each individual child achieves their potential involves not only ‘formal’ but also ‘informal’ schooling. Schools, parents, carers and their community all play a role. The task is achieved through team working and partnership. Those teams and partnerships will vary in size and duration, but each governing body plays a role as a part of them.

2.2.3 Parents and carers working alongside practitioners

Working as volunteer helpers, parents and carers can provide invaluable support to children, particularly within an early education setting – for example, by providing learning support to children. Activity 6 provides an opportunity to explore why it is helpful to work with parents/carers.

Activity 6: Why work with parents and carers?

Look at the nine statements below; each is a reason why practitioners should work with parents and carers. Think about each statement and the order they are presented in. In the course blog, record, giving reasons, whether you agree with each statement and the order in which you would rank the statements.

- Time out: Some parents and carers have extreme difficulties: emotional, social and financial. Providing facilities for parents and carers gives them time to relax and meet others while their children are looked after by trained staff.

- Practical skills: Some parents and carers lack the basic practical skills of childcare. Inviting them to stay gives them a chance to learn from staff and other parents and carers about, for instance, feeding, changing, hygiene and sleep.

- Knowledge of children: Parents and carers have the most knowledge and understanding of their own children. If they are available to share it, staff can make use of this knowledge in providing better care for children.

- Self-esteem: Some parents and carers lack self-esteem. By spending time with parents and carers, and encouraging the development of personal skills, staff can give them a sense of self-worth, and a feeling of confidence in their own abilities to look after children.

- Consumer rights: Parents and carers pay for pre-school provision either directly or through rates and taxes. As consumers, they should be involved in how these services are run.

- Partnership: Pre-school services are community facilities that should be responsive to the needs of those who use them. Staff and parents/carers have opportunities to develop informal, relaxed relationships, which make it easier for parents and carers to articulate their needs.

- Mutual support: People often derive the most meaningful support from those who have similar problems. Opportunities should be available for parents and carers to meet so they can share feelings, values, and difficulties, and support each other through them.

- Extra pair of hands: There are several tasks associated with the care of children that don’t require particular training or expertise: cutting up bits for artwork, washing toys, makings dolls’ clothes, preparing drinks. Parents and carers should be encouraged to do such tasks, so that trained staff can provide services requiring different skills.

- Improving understanding: Some parents and carers lack an understanding of children’s need for stimulation. Parents and carers should be encouraged to participate with staff in planning and carrying out play activities with the children. This will enhance their understanding of the value of play.

Comment

The statements illustrate the many potential benefits of collaboration. They also provide insights into the (assumed) needs of parents and carers. Most of the statements relate to the benefits that partnership offers to parents and carers. However, it is also important to remember the potential benefits for practitioners. They can be better informed through listening to parents and carers and taking account of their personal understandings of children – for example, the ‘Knowledge of children’ statement. Practitioners may also be supported by parents and carers in significant practical ways, as the ‘Extra pair of hands’ statement suggests.

Your own ranking may have prioritised benefits to parents/carers, to practitioners, to children, or to a combination of these. It is important to recognise that working closely with parents and carers is central to a child’s development, wellbeing and achievement.

A partnership involves parents and carers responding to practitioners’ ideas. A proven way of increasing goodwill, understanding and a sense of partnership between practitioners, parents and carers is by providing courses and workshops. These can take many forms, but essentially they involve proving a setting for parents and carers in order to:

- give them information

- explain what their children do in the setting

- provide information about their children

- help them to be more effective supporters of their children’s learning

- increase their confidence in approaching practitioners with queries and suggestions

- offer them skills and knowledge that may be useful to them.

It is important to have a wider sense of the scope of the partnership and the many practical ways in which it can be expressed. Partnership practice tends to be formulated by professionals – by policy writers, early years specialists, educational theorists and practitioners – but rarely by parents or carers themselves. So it is important to have a conception of partnership that goes beyond what professionals might feel is appropriate; a vision that leaves some space for creative and unexpected ideas from parents, carers, governors and children.

Practitioners have strong feelings about the kinds of partnership that are most supportive of their work in a particular school and there is considerable variation as to how educational settings interpret the notion of ‘partnership’. Making decisions about the type of partnership that would work in a setting involves a sense of what is feasible, given the nature of a parent and carer body and wider school community, but also a sense of what is appropriate in terms of children’s needs. The focus of any ‘partnership’ must be the children.

Table 1 provides a summary of the range of engagement parents may have with practitioners and a school. The table is based on the work of Pugh and De’Ath (1989).

| Parents and carers are not involved in their children’s learning | There are ‘active’ non-participants who decide not to be involved. They may be happy with what’s on offer, or very busy at work, or want time away from their children. Vincent (1996) calls these ‘detached parents’. There are also ‘passive’ non-participants who would like to be involved, but may lack the confidence to do this, or may be unhappy with the form of partnership offered. Vincent (1996) calls these ‘independent parents’. |

| Parents and carers support a setting ‘from the outside’ | These parents and carers become involved but only when invited, for example by attending events or providing money for learning resources. |

| Parents and carers participate in a setting ‘from within’ as helpers | These parents and carers help in ways such as providing assistance on outings, supporting children’s learning in the setting or running a toy library. |

| Parents and carers participate in a setting ‘from within’ as learners | These parents and carers attend workshops and parent education sessions. These parents and carers participate in parent forums, such as those in privately owned or corporate settings where there is no board of trustees, or parents/carers’ committee, as a place where parents and carers can discuss and interact with setting managers. |

| Parents and carers are involved in a working relationship with practitioners | These parents/carers’ involvement is characterised by a shared sense of purpose and mutual respect. For example, parents and carers:

|

| Parents and carers determine and implement decisions | These parents and carers are ultimately responsible and accountable for the provision of the setting and have the same responsibility and control as governors in the school - although few would take operational control, any more than school governors take on day-to-day management of a school. |

Section 3 builds on knowledge gained here and considers matters that impact the development of working relationships between parents, carers and practitioners in an educational setting. In turn these can impact and inform the work of a governing body.

3 Different perspectives

Parents, carers, practitioners and governors may have different perspectives on what a partnership is and how teamwork makes a contribution to a child’s education, wellbeing, safeguarding and development. This raises important issues for governors when working with practitioners, parents and carers, and for practitioners when seeking to involve parents and carers in their work with children. This section highlights four particular points that can help to inform the development of partnerships with parents and carers, and the work of the governing body in:

- recognising parents and carers as individuals

- understanding why some parents and carers decide not to become involved

- working with ‘challenging’ parents and carers

- acknowledging family structures.

3.1 Recognising parents and carers as individuals

Children are regarded as individuals and the same approach should be adopted with their parents and carers. However, because most parents and carers are more distanced than children, generalised statements may be made about the parent body as a whole, such as ‘Our parents and carers are supportive’, ‘Our parents and carers can be difficult’ or ‘Our parents and carers are not good at fundraising’.

Carol Vincent (1996) produced a four-way classification of parental positions with regard to practitioners. She identified four basic ‘types’ of parents and carers. Click on each one for more details:

Such classifications can sometimes support or refine our thinking, but they can also serve to reduce and under-represent reality. A major difficulty for many practitioners concerns their limited contact with most parents and carers. Practitioners spend a lot of time with children but very little time with parents and carers, unless the parents or carers are involved in a setting as a volunteer or paid employee, or if they are the practitioners (as in a playgroup). In the absence of detailed knowledge, it’s easy for assumptions to be made, which give rise to inaccurate stereotypes about parents and carers. Governors, unless they are a parent governor, spend even less time with parents and carers.

Time is at a premium for many parents and carers of young children, which may explain why many appear less engaged than they might be. It is vital not to classify parents and carers as ‘bad’ if they choose not to partner closely with the setting. It’s easy to make assumptions that give rise to inaccurate stereotypes about parents and carers, or, equally, mistaken notions about practitioners. Carol Vincent’s ‘detached’ and ‘independent’ parents and carers serve as a reminder of the reasons why some parents and carers choose not to be involved.

3.2 Understanding why some parents and carers decide not to be ‘partners’

Partnership between parents/carers and practitioners include sensitively formulating what is envisaged for the partnership, and listening to parents’ and carers’ views, reactions and wishes. But what might lie behind parents’ and carers’ seeming lack of engagement with practitioners? Activity 7 asks you to think about this in more detail.

Activity 7: Reasons for a lack of engagement

Based on what you have learnt on this course and your experience as a governor, note down five reasons why a parent or carer may not be able to fully engage with practitioners and the school community.

Comment

There are many reasons why a parent or carer may not engage with practitioners or the wider school community. Each parent/carer will have their own individual circumstances and reasons. The list that follows is not exhaustive; your list of reasons may include additional points, or points that are specific to your school:

|

|

It’s a long list – and provides examples of only some of the reasons for a lack of engagement or failure to turn up to meetings.

3.3 Working with ‘challenging’ parents and carers

Reports from a number of teacher-professional associations suggest that there has been an increase in disrespectful and, sometimes, aggressive behaviour from parents and carers. This may occur on school premises or on social media. According to Wallace (2002, p. 10), triggers might be:

- money, particularly requests such as paying nursery fees or for school trips

- children’s behaviour, particularly when parents or carers react strongly to practitioner concerns and complaints

- increased inclusion of children with special educational needs, which puts pressure on parents, carers and practitioners because the policy has not been matched by monetary and other support

- parents’ and carers’ own negative feelings towards authority figures.

Dealing with this behaviour requires considerable skill and time, and practitioners are not always trained to cope. In settings where challenging parents or carers have to be dealt with frequently, difficulties can be minimised by:

- a consultation process

- working with the parents and carers whenever possible

- finding opportunities to talk to each other.

It is helpful to set out clear expectations and guidance for parents and carers. Policies on behaviour, use of social media and complaints procedures can provide a clear framework and act as a reference point for parents and carers, pupils, and practitioners. As a governor you may already be familiar with such policies, which would be set and reviewed by your governing body.

With regard to the poor press that parents and carers sometimes receive, Margaret Morrissey of the National Confederation of Parent Teacher Associations brings proportion to the debate when she says:

The vast majority of parents – 95 per cent – are extremely supportive. As for the percentage who are not, they may not be interested, or too stressed or too busy. We look at what we can do to help them, rather than blaming them.

3.4 Acknowledging family structures

Practitioners and governors need a good knowledge of the many forms that family structures now take. It’s important not to assume that most children live with a mother and a father who are married. The image below (adapted from Tassoni, 2000, p. 272) summarises the main kinds of family arrangements that provide care for children. Click on each one for more details:

These represent just a range of some of the ways that a child may live with their parent(s). Many children also live with carers, such as grandparents and other family members, or may be in some form of care. Those arrangements may change over time.

It is important to avoid making assumptions about the nature of families when working with parents and carers. A practitioner’s knowledge of a child’s family arrangements depends upon what children and their parents or carers feel that they want to disclose.

4 Teamwork and leadership

In recent decades there has been an increasing emphasis on leadership in education, particularly in early years education. Your governing body will have contact with the school’s senior leadership team in a number of ways and senior team leaders often form part of the governing body.

In this section you will learn about:

- leadership in an educational setting

- different leadership styles

- how leadership is demonstrated

- how teamwork and successful leadership underpin each other.

4.1 The importance of leadership

The growing emphasis on leadership is based on the premise that effective leadership leads to improved outcomes for children’s care, learning and development. Rost (1991) describes leadership as a dynamic relationship located in a group of people, where leaders and collaborators work together to generate change.

Leadership can be viewed as an interactive, two-way process of influence. Whether or not an individual practitioner is designated, for example as ‘in charge’ of a department, all practitioners are still in a position to reflect on their own practice, and effect change and influence the quality of provision. The idea of leadership as an interactive process enables all those working in a school – whether as a practioner or in other roles – to work together in a culture of learning and shared knowledge to ensure that the school pupils are provided with an excellent education. Governors’ work forms part of that shared learning and knowledge.

Developing a team culture is a key aspect of leadership. The nature and structure of the team will vary according to context and the work to be done, but those in the team should be working towards common goals. Crucial to this way of working are communication and the strategies used by team leaders and members.

Activity 8: Leadership abilities

Reflect on your own experience of leadership, whether as part of a team or as a leader. Make a note of three abilities you expect a leader to demonstrate.

Comment

Leaders draw upon their own experiences, skills, knowledge and abilities. Successful leaders demonstrate a range of abilities. Your list of abilities will be drawn from your own experience and may include some of the following:

- confidence

- effective communication skills

- an ability to take responsibility

- an ability to make informed decisions

- flexibility

- ambition

- enthusiasm

- a willingness to learn.

This is not an exhaustive list and it is important to remember that individuals can show evidence of leadership without having a designated leadership role.

Leadership itself is a varied, fragmented process, enacted in a context of change and interwoven among day-to-day management tasks. Leadership is effective if it develops the leadership of those in the team. The role of the leader, therefore, is to consciously encourage others to lead themselves. The purpose of this is not to make the leader’s life easier, but to use everyone’s talents to best effect. Leaders play a significant role in enabling other practitioners to develop the necessary capabilities to enhance the quality of provision. It may be that practitioners should aspire to adopt the qualities of leadership identified by McCall and Lawlor (2000) who suggest that:

Leadership must be visionary. Leaders must hold some idea of the future, the distant horizon and full game plan and they need the capacity to maintain personal and team momentum on the journey towards securing the desired goal. They must also show rich human qualities such as an allegiance to a mission, curiosity, daring, a sense of adventure and strong interpersonal skills, including fair and sensitive management of those who work with them. They must be able to motivate themselves and others, demonstrate a commitment to what they espouse, release the talents and energies of others, have strength of character, yet remain flexible in attitude and be willing to learn new techniques and new skills.

Effective educational provision requires leaders, and all practitioners, to continually reflect on children’s experiences in their setting and, in partnership with families, governors and other professionals, to initiate change for improvement.

Leadership is the concern of everyone, irrespective of the role they hold in their setting. Think about what the particular qualities, skills and abilities of a leader actually are. Listed below is a summarised version of a selection of Reed’s (2009) personal qualities, skills and abilities that may characterise an effective leader.

Qualities of leadership in early years practitioners (Reed, 2009):

- possessing clear knowledge of strengths and weaknesses of self and colleagues

- ensuring effective transfer of information about children and families

- engaging in effective partnership working

- taking initiative and being innovative; encouraging colleagues to do the same

- leading by example

- finding ways to reflect on practice, and encouraging colleagues to do the same.

Working in early years settings is becoming increasingly complex and the roles demand high levels of knowledge and skills in practitioners and leaders. Jones and Pound (2008) use the phrase ‘inclusive leadership’, supporting the idea that early years provision is too demanding to be met exclusively by any one person. This suggests that each member of the whole team, to a greater or lesser extent, has a crucial part to play. In this sense there may be a designated leader, but the culture of the setting is not one of ‘leader and followers’ – rather, it is that of a team with everyone working comfortably in a climate of evaluation and reflection.

One common denominator in an early years setting is that a number of adults are involved. A home-based practitioner, for example, may not appear to be in a ‘team’ or be a ‘leader’ but may be working with other home-based practitioners, children’s centres and local support services. Early years practitioners need leadership skills for a host of purposes, including:

- leading the curriculum

- decision-making

- working with parents and carers

- developing policies

- working with other professionals or agencies

- working with governors

- dealing with conflict

- organising the school and learning environment.

4.2 The importance of teams

Although education in schools operates in different contexts, one thing that education and schools have in common is that a number of adults are involved. The complex and demanding nature of safeguarding and promoting children’s welfare, wellbeing, learning and development means practitioners cannot work in isolation from colleagues and other professionals.

Teamwork can be regarded as the building block of children’s safeguarding, well-being, development and education. Building, leading and working in a team is, however, a complex, ongoing process rather than a simple event. The commitment to working together in a multi-agency context stems from the belief that children’s needs cannot be boxed into health, social or educational compartments and should be viewed holistically.

The term ‘wider’ team includes professionals who may be less closely involved on a day-to-day basis but are needed to collaborate with, as and when appropriate to enhance a school’s provision and meet a child’s individual needs. This could include health visitors, speech and language therapists or educational psychologists.

Most early childhood leaders and staff appreciate that teamwork is important for the working conditions of their settings, and understand that what constitutes a team can vary. [...] Depending on the meaning given to the concept of team, parents may or may not be included in the broader definition. Regardless of its definition, the essence of a team is that all participants work together effectively to achieve a common goal.

A key aspect of teamwork is the extent to which all those involved in the team have shared views, values and beliefs. If team members are able to articulate these aspects they are more likely to develop shared understandings and to be an effective team.

4.3 Values and beliefs in the context of teamwork

It is widely accepted that the idea of ‘a common goal’ is core to understanding the notion of a team. But what is a ‘common goal’ and what does it look like? Rodd suggests that a team can be generally defined as:

A group of people cooperating with each other to work towards achieving an agreed set of aims, objectives or goals while simultaneously considering the personal needs and interests of individuals.

Rodd goes on to suggest that the following concepts are associated with teams:

- the pursuit of a common philosophy, ideals and values

- commitment to working through issues

- shared responsibility

- open and honest communication

- access to a support system.

It is commonly understood that teamwork involves individual interests being subordinated in favour of the group interests. This means that in order to create team spirit, the needs of the team take priority over the needs of individuals in the team. Teamwork is underpinned by a number of core values.

| Respect for persons | Recognising the dignity and uniqueness of every human being, and behaving in ways that convey that respect. |

| The promotion of wellbeing | Working for the welfare of all and seeking to further human flourishing. |

| Truth | Having a commitment to teach and embrace truthfulness; being open in dialogue, to what others have to say; and confronting falsehood wherever it is found. |

| Democracy | Believing that all human beings should enjoy the chance of self-government, or autonomy; and seeking within practice to offer opportunities for people to enjoy and exercise democratic rights. |

| Fairness and equality | Working towards relationships that are characterised by:

|

Having core values and beliefs and translating them into practice is not always as straightforward as it sounds. Working as a successful team can be difficult to achieve. The variable nature of settings and the range of individuals involved means there is no single route to successful teamwork. Certain constraints may prevent the practice reflecting the values and views of team members.

Developing a team culture with a comfortable climate of asking questions, checking understandings, reflection and evaluation is of paramount importance in improving educational experiences, and governing bodies have a key role to play in this.

If a core team is working effectively towards shared goals, the team will more readily relate and interact with others in the wider or external team. The drive towards partnership working has gradually been replaced by the more flexible notion of ‘integrated’ working and services encompassed in the term ‘multi-agency working’.

4.4 Putting this into practice

There are many aspects to your role as a governor. However, team working underpins the work of a governing body. Each governing body will draw upon the experiences and skills of their individual governors in different ways. In this way each governing body is unique.

Section 5 provides an opportunity to reflect on what you have learnt on this course and how it can be applied to your work as a governor. Through your studies you have explored team roles, team working, thought about leadership and learnt about ‘partnership’ working, a form of teamwork used in schools which brings together parents, carers, practitioners and others to support the education, wellbeing and development of children.

Governing bodies run their own development sessions. Your governing body may have undertaken a skills audit to inform discussion of committee membership, the roles of lead governors. A skills audit can be a useful starting point in forming an effective team and enabling governors to draw upon existing skills and knowledge, and develop new skills.

Activity 9: Teamwork and the governing body

Take a few moments to reflect on the work of your governing body. How do you undertake an evaluation to the effectiveness of the governing body on an annual basis?

Comment

There are statutory requirements that a governing body must fulfil including annual reports and meeting with parents (if petitioned). Guidance is provided for the content of such reports but what other activities do you carry out?

Strong governance is essential in the drive to improve school standards and there is a number of tools that a governing body can draw upon to assist their work.

The role played by teamworking within a governing body is important. To develop the team and provide some form of consistency tools such as regular skills audits and questioning approaches can assist. They also help provide a focus for discussion, planning and development. Table 2 contains examples of questions you may wish to develop for use in your own governing body meetings to provide a focus for discussion, consensus and common understanding and goals. As you have learnt these all make a contribution to successful teamwork.

Right skills Do we have the right skills on the governing board? |

|

Effectiveness Are we as effective as we could be? |

|

Role of the chair Does our chair show strong and effective leadership? |

|

Strategy Does the school have a clear vision and strategic priorities? |

|

Engagement Are we properly engaged with our school community, the wider school sector and the outside world? |

|

Accountability of the executive Do we hold the school leaders to account? |

|

Impact Are we having an impact on outcomes for pupils? |

|

Footnotes

(Adapted from NGA, 2015)As a governor you are involved in consideration of a wide range of documentation and data including performance, achievement and budget. You may be called upon to find a solution to issues that have arisen, or you may be involved in planning for change. Building a common understanding, setting common goals and drawing upon governor’s expertise and experience is helpful in addressing problems and planning for change. Table 3 contains a suggestion for a questioning approach which draws on team working and can help build a common understanding and shared solutions and objectives.

| Identify the issue |

|

| Analysis |

|

| Conclusions |

Provide an overview and set out important causes of the problem and significant features of the analysis. |

| Recommendations |

State any assumptions have been made. |

| Advantages, disadvantages and implications | Consider these carefully. Set out how particular disadvantages or negative implications might be addressed Making sure that any plans are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time bound) |

You should now attempt the final activity.

Activity 10: My work as a governor

Think about what you have learnt and make notes on the following.

- What do you now understand by the phrase ‘team working’?

- What teams are you involved in as a governor?

- As a governor do you lead any teams?

- What are the strengths of team working?

- Does your governing body have a ‘common purpose’?

- How does ‘partnership’ working benefit the education of pupils?

- What understandings, values, attitudes and beliefs relating to how children learn and develop do you share with others on the governing body?

- What things will you do differently in your role as a governor having studies this course?

Comment

There are no correct answers to this activity. Your responses will be unique and based on your own experiences and understanding. A willingness to learn, adapt and contribute all form part of a governor’s role. Learning is an individual experience and we hope that through your studies of this course you have gained a greater understanding of team working and the role it plays in your work as a governor. You should now be able to identify your own preferences in terms of team roles and we hope you find this understanding beneficial to your work as a governor.

As a governor you make an invaluable contribution to your school community and to the education of pupils in Wales. As a governor, you (Governors Cymru Services, 2007):

- are a volunteer

- care about teaching, learning and children

- represent those people with a key interest in the school, including parents, carers, staff, the local community and the LA

- are a part of a team which accepts responsibility for everything a school does

- have time to commit to meetings and other occasions when needed

- are willing to learn

- are able to act as a friend who supports the school but is still able to cast a critical eye upon how the school works and the standard it achieves

- act as a link between parents, carers, the local community, the LA and the school.

As a governor your work is also informed by ‘The 7 principles of public life’ (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 1995).

5 Compulsory badge quiz

Now it’s time to complete the compulsory badge quiz, which includes nine questions.

You can open the quiz in a new window or table and return to the course when you are done.

Remember, this quiz counts towards your badge. If you’re not successful the first time, you can attempt the quiz again in 24 hours.

6 Conclusion

This course explored a number of areas relevant to your work as a school governor. Having completed your studies, you should now have a better understanding of the important role teamwork plays in a school community and how ‘partnerships’ and team working can be used to support and develop the education of pupils and maximise their opportunities.

Teamworking is also underpinned by a sense of common purpose and goals. In a governor setting this is informed by government policy and aspirations. Kirsty Williams, Minister for Education stated, ‘Our national mission in Wales is to raise standards, raise the attainment of all children and ensure we have an education system that is a source of national pride and public confidence’ (Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government, n.d. 2). As a governor you play a role in that mission and the work of your governing body is underpinned by teamwork.

School governors have overall responsibility for the conduct of their school and within that particular responsibilities to promote high standards of education and the welfare of pupils. All of this is contained in a legal framework. Being a governor is both rewarding and challenging, but for governors to undertake their responsibilities and duties effectively and efficiently, they need guidance and support.

You should now:

- Understand the importance of teams in an educational context

- Understand the importance of working in ‘partnership’ with others in an educational context

References

Acknowledgements

This free course was written by Carol Howells.

Except for third party materials and otherwise stated (see terms and conditions), this content is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Licence.

The material acknowledged below is Proprietary and used under licence (not subject to Creative Commons Licence). Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources for permission to reproduce material in this free course:

Images

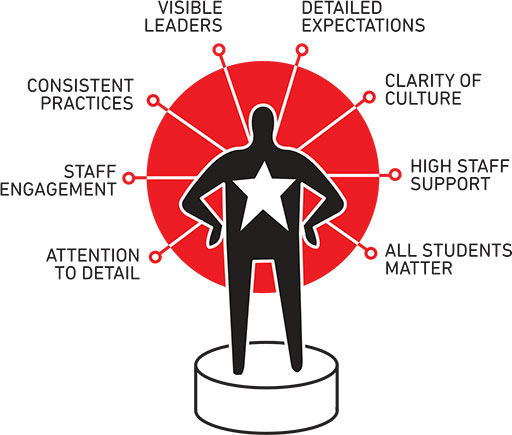

Cover image: SolStock/Getty Images; Figure 1: Bennett, T. (2017) Creating a Culture: How School Leaders Can Optimise Behaviour, available at https://www.gov.uk/ government/ publications/ behaviour-in-schools, reproduced under the terms of the OGL, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/ open-government-licence; Figure 2: Welsh Government, available online at https://gov.wales/ school-governance, reproduced under the terms of the OGL (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/ open-government-licence/ version/ 3/); Section 2.2.1: school sign, Tim Scrivener/Alamy Stock Photo; Section 2.2.2: teacher and children in classroom, Gregg Vignal/Alamy Stock Photo; Figure 4: taken from http://www.childreninwales.org.uk/; Figures 5 and 6: Education Begins at Home, Llywodraeth Cymru/Welsh Government; Section 3.3, challenging parents and carers: SDI Productions/Getty Images; Section 3.4: family structures, adapted from Tassoni, P. (2000) Certificate Child Care and Education (2nd edn), Oxford: Heinemann; Section 4.1: importance of leadership, Edgars Sermulis/Alamy Stock Photo; Figure 12: Rawpixel Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo; Section 4.3: values and beliefs in the context of teamwork, Rawpixel Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo.

Tables

Table 2, adapted from National Governors' Association (2015) ‘Key questions every governing board should ask itself’ (2nd edn), available at https://www.nga.org.uk/ getmedia/ 028dfea6-8313-4339-96ed-fa61e0769fe4/ Twenty-questions-second-edition-2015.pdf.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.