Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 1:25 AM

8 Lively encounters

Introduction

In this section of the course we return to the idea that empowering research relies on

New materialist scholarship sees the material world as made up not of fixed, stable entities, but as lively, relational and in constant flux (Fox and Alldred, 2017). Liveliness arises as a consequence of the agentic capacities of living and non-living things that researchers encounter through their actions and activities. This perspective draws attention away from studying what things are and towards what things do, i.e. their

This way of thinking ‘displaces the human subject’ as the centre of agentic action and assumes that assemblages of humans, non-humans, sociomaterial and discursive entities are connected in agential ways. Gherardi (2019: 5) uses the label ‘posthuman … practice-based studies’ to refer to these ‘situated and emergent processes’. She uses the concept of ‘affective ethnography’ to emphasise the importance of the lived, sensory experience of the researcher in the

Visual participatory research, and creative methods in studying memory and change

In Film Focus 13 and 14, researchers in organisation and media studies explain how they used creative, imaginative methods to develop a more empowering approach in their research. These accounts illustrate the importance of embodied encounters in enabling people to assemble in time and place and tell their stories. They also highlight the elusive, multiple and continually evolving realities that researchers encounter.

Activity: Film Focus 13, ‘Visual participatory research: from development to management studies’ – Lauren McCarthy, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK

Watch the film and make your own notes in response to the following questions:

- Can you identify a connection between the reluctance to use new visual methods and the fear of shifting the balance of power in a situation? How would you address this with people in positions of power?

- Think about how visual methods can be used to articulate and elicit what is usually taken for granted in a situation.

- How would you address potential shortcomings of visual methods; for example, reinforcing exclusion of those who cannot express themselves visually?

Transcript

So one of the toolkits that I alighted on when I started my PhD was something called the Gender Action Learning System, or GALS for short. And it is a toolkit of different visual methods, but it’s also a methodology in that it comes with a set of principles and assumptions about how we should work alongside our participants. And so these images on the left, there’s me in 2013 leading one of these workshops. And on the right, there I am in 2016.

So this is a methodology that was created by development consultant Linda Mayoux in the early 2000s. And she developed it working alongside, I think, the International Labour Organisation, again, trying to find an answer to how can we best access men and women’s experiences of supply chain work. And this is just one of the visual tools that she developed. There are other ones that she’s used.

And as a toolkit, it’s been adopted by lots of different NGOs. So Oxfam, I think Action Aid, and others have started to use this. This is the gender balance tree. And I went to Ghana working with NGOs in the area. And I ran workshops with Ghanaian farmers that we knew were selling their cocoa to a co-operative which the UK company was then buying from. So that’s the supply chain connection.

So we ran workshops in different villages. At the beginning, the NGO was quite keen on having comparative samples. There were some villages where the men and women hadn’t had any interaction with CSR and some villages where they had. So they wanted a sort of comparative case approach. It didn’t really work very well, which we can talk about that in a bit.

But the idea was run workshops in these villages with twelve farmers, six men and six women. And we would together work through this gender tree. And each farmer would draw their own. So when I started to explain this process to the NGO who I was working with at the time, they were very, very resistant.

They were incredulous that we would be able to do this with the farmers, many of whom have not been to school. They said, ‘Oh, the women in particular will never have held a pen. You can’t ask them to do this, they’re just going to draw rubbish.’ So already, you were getting that power play coming out that there’s one way of doing research and one way of talking to these farmer and it’s not going to be using drawing. So that’s been quite challenging.

So the gender tree, I’ll try to explain it quickly. But it’s almost more like a diagram. So it’s not about freehand drawing here, it’s more about using symbols and where the farmers place these symbols on their drawing to capture the political and the economic and the social dimensions of gender for those people. So this is a stylised version that we created for the NGO report after the project had been finished.

So everyone draws that tree trunk. And then at the bottom of the tree, the roots is the labour that men and women put in to that joint household. So on the left, women would draw the kinds of work that they would do. So that would be cocoa work, spraying pesticides or weeding and so on. But we also included other entrepreneurial kinds of work so what were they doing on the side to bring extra money? And importantly, what kinds of unpaid care work, domestic work were they doing?

So women drew their responsibilities on the left, and then they drew their partner’s responsibilities on the rights. And all of the farmers we spoke to were in heterosexual relationships. In the middle, they could draw tasks they shared together. At the top of the tree is who gets what out of all this work so who makes the decisions on expenditure? So on the left, expenditure that women decide on, on the right, what men make decisions on, and in the middle what’s shared.

And around this tree we drew ownership: who owns the land for example, who and who is responsible for the banking? And so the idea is that as the farmers drew their tree, it started to create a topography of gendered work and gendered reward.

So on the left, this is one of our female participant’s trees from 2013 where you can see she circled different symbols that relates to the time that she spends most on. So again, we can see here that does this is have a colour on it? No. There’s an image of a person with a bucket on their head. So that was the symbol for collecting water from the well.

She’s saying, this is my side of the tree, I spend a lot of time per day collecting water. So we start to be able to also look at time use and how that’s shared between cocoa farming households. Down the bottom, you can see a pot over some sticks. That’s the symbol for cooking. A lot of the women in the study said, ‘We spend most of our time per day on cooking-related responsibilities.’

Yet, she’s also doing an awful lot of cocoa work but wouldn’t call herself a cocoa farmer. So some of the words that women were using when we ran the groups after the drawing were, ‘I’m the helper, I’m the cocoa helper. My husband’s the farmer.’

But yet, when we refer back to the drawings that everyone had just done we could say, ‘Oh, but look here, I can see that you do the weeding and you’re doing the planting and you’re doing all these other tasks.’ And they go, ‘Oh, oh yeah, maybe I’m a farmer, then.’ And so the utility of using the visual alongside some kind of focus group or conversation afterwards was quite a powerful one.

And I’ve just included here the original sheet of symbols that I co-created with the NGO before we went out into the villages. Now in Mayoux’s original method she suggests that the symbols are created by participants in the field, because then it’s more participatory, more power goes to them to decide how would we do cooking or how would we draw land ownership.

But here’s the rub, and the reality of doing field work sometimes was the workshops were already going to be three hours long when we brought in the drawing process and the interviews and so on plus all of the meeting of the elders at the beginning of each meeting and the processes that you need to go through. And these farmers are extremely busy. And three hours out of the day was already a huge amount of time.

So we had to make the decision of where could we cut time. And one of those ways was to say, ‘OK, let’s create symbols ourselves first and provide that almost as a recipe card for farmers to choose from, then they can draw them on their gender tree.’ We did also say to them, ‘You can draw your own symbols if there’s other things that you do, other jobs that we haven’t even thought of.’

But it didn’t really work because we’d already set the scene, we’d already presented what kinds of symbols should look like. And so that is one of the challenges of this and one of the regrets is when I’ve used this particular method is that I don’t think it has given enough power to the participants in that way.

Drawing in itself as a method can be both empowering in the sense it gives us another way of illustrating our experiences, perhaps a non-verbal way of trying to draw what our experience is. But it can also be disempowering because you might not feel comfortable trying to visualise, you might not have been to school, which is for most of our participants is the case. And so that might be extremely anxiety-inducing situation to be in.

And I run these sessions often in groups. So you can imagine people might be looking like, oh, oh, they’re really good at drawing cocoa beans. I don’t know if I can do that. And so I don’t want to present drawing and visual participating methodologies and as a silver bullet to empowering methodologies. We still need to be cognisant of power and how it plays out within communities that we work in.

I think we shouldn’t underestimate the power or the empowerment that can come from enabling people to pick up the pen or the stick or the chalk or whatever it might be. This is a household drawing by female participant in Western Ghana. She’s drawing her household and she’s circling who has the most power – ‘Who’s the decision-maker?’ is how we put it. And she circled her husband, and she’s also circled the baby next to the husband.

Drawing can open up new ways and new conversations. So this can help, I think, not just the participants themselves but some of the NGO staff. I said how they were really resistant about this. They were like, the women in particular can’t do this, they can’t do it. They could, and they did, and they enjoyed it, mostly. And so some of the NGO staff said to me, ‘I’ve learned a lot about the capacities and the assumptions that I made about the people that we work with.’

And so there was an empowering element to this method that I hadn’t foreseen, and it wasn’t where I thought it was going to be. It was actually on working with NGO staff to help them recalibrate how they thought about their ‘beneficiaries’. And in 2016, we met a lot of effort to actually train the NGO staff in using these kinds of methodologies so they could lead, not me.

We recommend that you keep notes of your answers to these questions so you can return to them during the course.

Activity: Film Focus 14: ‘Creative methods in studying memory and change’ – Emily Keightley, Loughborough University, UK

Watch the film and make your own notes in response to the following questions:

- Reflect on how audio-visual resources such as film can be used to promote thought and conversation about past and current events. How useful are these resources in exploring diverse points of views?

- Reflect on the time, resources and skills needed to use audio-visual methods.

Transcript

– project that I’m working focuses on the ways in which these are mobilised by South Asian communities living in the UK now with these complex relationships to the end of empire.

OK, so the research questions that inform the projects are what memories of Partition circulate within South Asian communities living in Loughborough and London, how are these memories communicated over time and space so we’re doing some work with people from back home, families and friends of people living in Tower Hamlets and Loughborough. How do social practices and processes of remembering partition inform the reconstruction and idea of community itself, as well as inter-communal identities, and what is the role that these memories in the articulation of a sense of identity and belonging in relation to labels such as British Asian, but also in relation to a sense of Britishness itself. So we were interested also in the emergence of national and subnational identity.

So the particular methodology that we’re using is a three-fold methodology which draws heavily on ethnographic methods. So we’re starting off and I’ll talk about the main project to start with. We’re starting off with community activities. The project is based on partnerships with existing community organisations.

So in Loughborough, we worked with an organisation called Equality Action, and in Tower Hamlets, we worked with the council. And using those two partners, we sort of migrate out into joining different community organisations, literary organisations, social clubs, religious organisations, those kinds of things, and work with these groups to develop community activities where people can articulate their memories.

So the idea is that these are code-designed activities. And to date, we’ve got a range. We’ve used film-based activities film screenings, sharing with the large groups, small groups, working with people to talk about those films and how they’re significant. And I’m going to use this as an example in a moment if I have time. We have storytelling workshops.

We’ve had photography workshops where some of our groups have photographed their local environments, talked about their memories of that local environment, brought in their own personal photograph collections, made exhibitions and shown them at the local mela and things like that. We’ve done timeline-based activities. So we’ve looked particularly at textiles and Indian fashions and the ways in which those have changed over time and used that as a basis for workshops.

We’ve done cooking sessions because food is so intimately connected to memory. Dance workshops and also animation workshops where people have been able to create photographs that they wish they’d had that they don’t have either ones that have gone missing or been lost, or fantasy photographs that they never had in the first place and animating those in various ways.

So these are all arts-based, largely, research. And we’re conceiving of this in the same way as Jones and Levy in a quite general sense that ‘any social research that adapts the tenets of the creative arts as a practice of the methodology, the arts may be used during data collection, analysis, interpretation and/or dissemination’. That’s how we’re interpreting art space research. So these are our creative methods.

And from these community activities, we’re obviously doing participant observation all the way through. Some of them involve recorded conversations as part of the activities themselves, but then these also move into more traditional ethnographic methods like interviewing. So pulling people out, asking them about it, and then getting them to reflect more autobiographically on their experience. And sometimes we do that in family groups or small groups as well depending on the activity and the people that we’re working with.

– like to do now because I think I’ve got enough time is just spend a bit of time talking about one case study or one strand of work that we’ve done through this project. Has anyone seen Viceroy’s House, the film? One, two, oh, a few. OK, that’s great.

OK, so one of the things that we did was run a film screening of Viceroy’s House. In fact, we didn’t run one film screening. We ran about eleven or twelve of these film screenings with different community groups across our two research sites. We showed the film and then provided food, got people to start talking about the film, their thoughts on it, how they felt about it, linking it into people’s own autobiographical experience. And then we also at the same time have done a textual analysis of the film, understanding how it operates.

Viceroy’s House is made by the filmmaker Gurinder Chadha, who is sort of a self-labelled British Asian filmmaker. Her career sort of emerged in that kind of Britpop/New Labour high point in the mid to late 90s. And she made this particular film, Viceroy’s House, that portrays events surrounding the partition of British India into Pakistan and India. And it’s an Upstairs, Downstairs take. So it’s actually very much like Downton Abbey in that regard.

So you get the sort of elite-level representations focusing on the Mountbattens, for example, and Nehru Jinnah Gandhi. And then you get the sort of downstairs perspective that looks at the servants in the viceroy’s house at this moment of high political drama.

So what did our respondents make of this? I’m going to try and sort of whip through this relatively quickly. We had a huge diversity of groups. We had Sikh groups, Hindu groups, Muslim groups, We had Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Indian groups, and people belonging to different generations as well. So we were trying to get as many different responses as we could.

But one of the most interesting findings was that all groups initially said that they enjoyed the film. I mean, our reading of this film is very much that it does reproduce a colonial nostalgic perspective, and this is deeply problematic. But in the first instance, everybody said there was something nice about this film. They liked it. It was a feelgood film.

And one of the most favourable readings were made by the older female group of Gujarati women that we spoke to. Participants in our Gujarati focus group picked up on the benign characterisations in the Mountbattens, who in the film, serve as the face of British colonialism. And they say they feel sorry for the viceroy, which was quite a surprising comment to us. You know, all they were trying to do is sort it out properly, but there were barriers in the way. He must’ve lived with that guilt all his life. Which kind of surprised us, you know. This kind of very generous, I would say, reading of the film.

They loved the beginning because of the unity between the different communal groups. In the beginning, everybody was equally discriminated against. And they compared this with living in the UK now, which they feel mirrors this communal harmony. And certainly this came from one of our midlands groups, who were very invested in the idea of a contemporary multicultural discourse.

The older Gujarati Hindu women in this focus group also interpreted Chadha’s British Asian perspective in the same way that Chadha herself describes her intention to present a balanced film that promotes understanding and reconciliation. You know, they agree that she was trying to portray all three major religious communities and she wasn’t trying to push her own particular religious perspective. So in this sense, the women interpreted it an attempt to be even-handed in the representation of the various groups involved in partition is bound up with a specifically British Asian perspective, that this was characteristic of being British Asian.

OK. Then later on in the conversation, the violence of the colonial enterprise emerged as the topic. I asked the women whether they thought the film should have focused more attention on this, there’s hardly any violence shown in the film at all either perpetrated by the British or inter-communal violence. They responded that they thought it shouldn’t, specifically drawing attention to the ways in which telling particular histories can impact on contemporary experiences and relationships.

And there was this focus on keeping it in the past. They didn’t want it intruding on the present. They wanted to move forward.

So at first glance, this appropriation of colonial nostalgia seems rather surprising in the sense that we hadn’t anticipated this idealised representation of colonialism and it being seen in a positive way by any of our South Asian communities in the UK.

‘When we’re looking at recent theorisations of nostalgia, there’s an increasing recognition that idealised pasts have the potential to actively stimulate progressive orientations to the present and future. Indeed, the women suggested it’s precisely these kinds of positive portrayals of the past in which nostalgic longing relies which afford these possibilities in relation to their contemporary experience.’ So you can see that they’re talking about needing to work together, that everybody’s human.

They creatively use the universalist discourses from the film to construct an imagined multicultural present and future in which differences are flattened out. They felt only the positive presentation of the past could achieve this. A more critical representation, which they were clearly aware could have been made, was actively rejected as potentially undermining this creative use. So they were using the film as a staging point for their articulating their desire for an experience of a somewhat idealised cosmopolitan social life in which inter-communal tensions are consigned to a past somewhat disconnected from the present.

Of course, it is also the case that Gujarat wasn’t partitioned and that many of these women came through East Africa. They had a very different relationship to empire and colonialism and partition itself. So they weren’t in India when it was partitioned, although they did have very deep familial connections at the time. But all of these women experienced expulsions from East Africa. And in interviews elsewhere, they drew on the direct parallels between their parents experience of partition and their subsequent expulsions from Zanzibar, Uganda, and other places.

The positive response to the film and the mobilisation of the nostalgic representations of empire in the interests of a multicultural future by this group are also at least in part explained by the fact that many of the participants had enjoyed a middle class lifestyle in East Africa before migrating to the UK. While various family members had been affected by partition, their relationship to the colonial administration was far more complicated.

The investment in a narrative of continuity from communal harmony under colonial rule to communal harmony in a former colonial power with partition violence as a discreetly bounded aberration served them well. As a sanitised depiction of empire, the film becomes a pedagogic tool in the interest of suppressing dissent and disunity in a contemporary context.

How am I doing for time? I’ll just give one other example from the focus groups before I pull it together. We had hugely different readings of the film from our Muslim focus groups, both Bengali Muslims and Indian Muslim groups Bangladeshi and Indian Muslim groups- in a contemporary context. And they read the film as deeply, deeply Islamophobic. ‘And their relationship to colonial nostalgia, as it’s configured in the film, is fundamentally different.’

In contrast to the Gujarati group, Bangladeshi and Indian Muslim groups were more complex. They also said that they like the film, it was light-hearted, there was a romance, it was nice, you know, all the rest of it. But underneath that, as conversations emerged, they vehemently rejected the film as balanced, this idea of that balanced. And there was a group of Pakistani Muslims in particular in their late 20s and 30s who felt that the film presented Muslim characters in an overly negative light.

And this is contested in the critical literature on Viceroy’s House as a film. You know, one of the particular things that she says is, ‘It doesn’t surprise me; I’m used to it now. You know, forget Hollywood in the history books. It’s in what we read in the media and everywhere. But it still disappoints me. It disappoints me because we’re meant to be the enlightened part of the world. We’re meant to be no, but it’s true, were meant to be impartial, and we say so many things, yet we’re not.’

There’s this idea that in the UK, this shouldn’t happen because we claim this status of impartiality that Chadha herself is claiming in positioning herself as British Asian. And they feel that that claim is not made good. ‘So the accusation of insincerity is directed at Chadha for clearly not stating that she was making a film from an Indian perspective and instead claimed to provide a British Asian take on partition.’

When asked what perspective the film did provide, they specifically said Hindu and British. This criticism conflates being anti-Muslim with anti-Pakistani and results in the most oppositional reading of the film that was made across all of the groups.

The Indian Muslim group also perceived the same anti-Muslim tendencies within the film, but perhaps somewhat unsurprisingly, were more circumscribed in their assessment, saying there were times during the film that it seemed maybe that the Muslim men were more angry and causing the problems. And we felt that, oh no, not the Muslims again.

You know, there was this feeling of having to kind of not be too aggressive in the rejection of the film. But they were unwilling to criticise Chadha personally for this. They insisted that the film was still good, and one participant said that Chadha was just making the film from her own perspective and background and she shouldn’t be blamed for that.

As British Indian Muslims, their own sense of occupying competing sociocultural positions is keenly felt, and may to some degree explain a reticence to criticise Chadha’s own attempt to navigate such a challenge. The universalising discourses that underpin colonial nostalgia in the film were again interpreted from the contemporary reality of the women’s social and cultural experience. As Muslim women, this group are more structurally marginalised and politicised in the UK than the Gujarati women, and they read this marginalisation in the film rather than focusing on the universalist frames that it employs.

The British Indian perspective is presented in and around Viceroy’s House, which flattens out differences between various communities implicated in partition. It’s clearly not so easily inhabited for these women.

We recommend that you keep notes of your answers to these questions so you can return to them during the course.

Stories from the field

Avilasa Sengupta: leaving the field

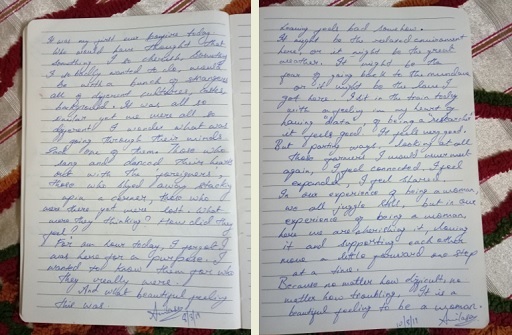

You will recall Avilasa’s story from the field in Section 1. On entering the field, Avilasa, a researcher on the project team, identified her ethical dilemmas and noted down self-reflexive questions in her diary in the early stages of her research. As you will see from the diary excerpts below, Avilasa quickly went from questioning her place, her positionality, and her methods, to feeling as if she was part of the women’s group she studied and gaining a sense of empowerment as a woman from her research encounters. Here are two extracts from Avilasa’s research diary:

8 March 2019

It was my first ever bonfire today. Who would have thought that something I so cherish, something I so badly wanted to do, would be with a bunch of strangers, all of different cultures, castes, and backgrounds[?] It was all so similar yet we were all so different.

I wonder what was going through their minds. Each one of them. Those who sang and danced their hearts out with the ‘foreigners’, those who shied away stacking up in a corner, those who were there yet were lost. What were they thinking? How did they feel?

For an hour today, I forgot I was here for a purpose. I wanted to know them for who they really were.

And what a beautiful feeling this was.

10 March 2019

Leaving feels bad somehow.

It might be the relaxed environment here, or it might be the great weather. It might be the fear of going back to the mundane or it might be the love I got here.

I sit in the train today with a feeling in my heart of having ‘data’, of being a ‘researcher’[,] and it feels good. It feels very good. But parting ways, looking at all those farmers I would never meet again, I feel connected. I feel expanded, I feel shared.

In our experience of being a woman, we all juggle still. But in our experience of being a woman, here we are cherishing it, loving it and supporting each other move a little forward one step at a time.

Because no matter how difficult, no matter how troubling, it is a beautiful feeling to be a woman.

Activity

Avilasa’s diary

Read the extracts from Avliasa’s fieldnotes above and make your own notes in response to the following questions:

- Based on her diary entries, how and why do you think Avilasa’s positionality changed over the four days she spent conducting her research?

- How do you think the research participants enabled Avilasa to feel so welcome?

- What words would you use to describe how Avilasa benefited from her encounters?

We recommend that you keep notes of your answers to these questions so you can return to them during the course.

Comment

From Avilasa’s closing statement, it could even be inferred that Avilasa felt enlivened by the research. Her four days of research was a learning experience that not only enabled her to observe and document participants’ ecofeminist practices, but also to participate in those practices. Being invited to participate with and learn from research participants meant that Avilasa felt empowered through her embodied and lively learning encounters.

As you learned from the short film by Avilasa in Section 3 and the slideshow of Avilasa’s images of Earth Day in Section 4, the NGO she studied made space for equality and for voices to be heard. In Film Focus 10, Nirmal Puwar discusses this as ‘projecting it out there’. Using Spivak’s terminology, space is made for the subaltern to be heard. So whilst in everyday life young Indian women might feel disempowered by dominant and problematic patriarchal logics, in her research Avilasa discovered a space that had been created to empower and embolden women to lead new initiatives. Avilasa clearly left the field feeling more vital and motivated than when she first entered it.

Avilasa’s project is indicative of the spirit of empowering methodologies, which, when conducted ethically and equitably, can provide transformative experiences that open up new ways of seeing, sensing and feeling, or offer inspiration to take radical actions that can enable significant change.

Recommended reading

Back, L. and Puwar, N. (2012) ‘A manifesto for live methods: provocations and capacities’, The Sociological Review, 60: 6–17. Available at: https://pmt-eu.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/ permalink/ f/ gvehrt/ TN_wj10.1111/ j.1467-954X.2012.02114.x (accessed 1 October 2019).

Fox, N.J. and Alldred, P. (2017) Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action, London: Sage. Available at: https://pmt-eu.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/ permalink/ f/ gvehrt/ TN_sageknowb10.4135/ 9781526401915 (accessed 1 October 2019).

Gherardi, S. (2019) How to Conduct a Practice-based Study: Problems and Methods, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Available at: https://www.e-elgar.com/ shop/ how-to-conduct-a-practice-based-study?___website=uk_warehouse (accessed 1 October 2019).