Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 13 March 2026, 5:57 AM

1 Introduction to empowering methods in organisational research

Introduction

Empowering methodologies in organisational research will explore how management and organisation studies can be revitalised by developing more empowering ways of doing research. The concept of empowerment enables consideration of the power relations between researchers and research participants, as well as powerful cultures and institutions within which they are embedded. Empowering methodologies are understood as an ‘ethical stance in qualitative research’, where the purpose is to ‘create an empowering space in which research participants share power with researchers’ (Davis, 2012: 261). This includes creating specific ‘moments of empowerment’ in the course of interactions between researchers and participants, when traditional power imbalances are disrupted, as well as by systematically developing methodologies that seek to challenge established inequalities (Ross, 2017).

Empowering research involves researchers seeking to equalise ‘the inherent power differential in their relationship with research participants by paying attention to issues of voice, interpretation, interactions, dialogue, and reflexivity’ (Davis, 2012: 261). The logo for this course is based on the image of a human ear. This is intended to draw attention to the importance of

What are empowering methodologies?

To understand what is meant by empowerment, we must also reflect on what we mean by power. There are many ways of understanding power, including ‘power-over’, involving domination or control, as well as a Foucauldian understanding of power, as distributed and circulating through the operation of social structures and cultures (see Lukes, 2004 for a summary). There are also many sources of power inequality that affect interactions and relationships between research participants and researchers, including gender, ethnicity, age and class. Here, we focus on a particular structural source of power that has a significant influence on how organisational knowledge is produced today. This stems from

In organisational research, the phenomena that are the focus of study include businesses, non-profit and public sector organisations, as well as organisational practices that occur informally, i.e. outside traditional institutional structures. The primary purpose of organisational research is to enable better understandings of how and why social practices are organised. Knowledge produced through organisational research thus has both an academic purpose (by enabling a contribution to knowledge) and a practical purpose that arises from the possibility of using that knowledge in constructive ways, which are potentially of value to members of organisations, and those who are engaged in organisational practices, as well as to wider societies within which organisations are located. The determination of research value is understood here as an ethical, rather than a practical, instrumental judgement, which is based on moral assessments about improving society in the broad public interest, rather than (for example) enhancing shareholder value of private businesses in a way that increases, rather than decreases, social inequalities.

We explore further the question of what research

Activity: Film Focus 1, ‘What are empowering methodologies?’ – Emma Bell

Watch the film and make your own notes in response to the following questions:

- What is your experience of power relations in research?

- How does becoming aware of power relations make you feel?

- When doing research, how might you do things differently in order to empower yourself and others?

Transcript

So why do we need empowering methodologies in management and organisation studies research? We need to acknowledge the relational processes to a much greater extent of how knowledge is produced. And that includes between researchers, as well as between researchers and research participants. So we’re not seeing empowerment as something that is done to the people we do research on. We’re seeing empowerment as something that potentially extends to all of us.

It involves looking for what is unsaid. It implies that there are silences. There are things that we don’t consider. And so we’re trying to open ourselves up to those possibilities – what might we be able to look at through this concept of empowerment? And it implies much more situated knowledge. The pursuit of generalisability as a kind of positivist goal is something that empowerment does not subscribe to, because empowerment would be about the embedded, situated nature of experience as the source of knowing. And there is a critical aspect to this, because through empowerment, we’re seeking to surface the possibility of hearing voices that are obscured, that are overlooked, of understanding questions of difference, of othering, of oppression and inequality.

Now, you might say that there are plenty of methodological terms out there already that enable us to do these things, such as critical management research – I’m a critical management studies scholar, so that would be something that I would be familiar with – participatory organisational research, participatory action research, collaborative inquiry, feminist and decolonising methodologies.

So why another term, apart from the fact that maybe it helped us to get a grant? So one possibility is that it’s an umbrella concept, a kind of loose, fuzzy notion, something that we can shelter under, to use the umbrella metaphor. And it’s deliberately loose. It’s deliberately loose to reflect the messiness of what research actually involves. So we’re interested in that messiness, and we don’t want to pin it down too much. And so there’s a deliberate vagueness to this notion of empowering methodology.

It’s also potentially a boundary object, an abstraction that has the power to speak to different audiences. And I think that is something that I was conscious of when I wrote, together with Sunita, the grant application, because if I write ‘critical’ and ‘oppression’ and terms like that into the grant application, that may not sit too well with certain readers. So there was a strategic aspect to the use of the term, and one that potentially means that you have a springboard in terms of the empirical work as well.

And thirdly is the possibility that it’s an alternative to ‘emancipation’. Now, emancipation is associated with critical management studies and with the Marxist tradition of critical ethnography, for example. And although there are a lot of good things about that, a concern that I have is around the way in which it potentially ascribes a kind of priority to the researcher as the person who’s able to see oppression and help other people to overcome it. So the source of emancipation – and that is something that emancipatory researchers are aware of. It’s not as if they’re unaware of that. But there are certain kind of potential problematics around seeing emancipation as the purpose of research, which the researcher is able to facilitate.

So where is the power in research empowerment? And as Jacques says in relation to management empowerment, there is often a use of this term in applications where there’s very little sharing of authority, reward or decision-making. So we need to question, I would say, the motives of ourselves as researchers and make sure that we’re not seeking to passively bestow empowerment or some label of empowerment. So it’s problematic in that respect.

And we need to potentially think about power differently. So I think implicit in some research processes is an assumption of the possibility of power over that has to be insured against. So I’ve done some work looking at ethical review processes – which are now very common in universities, you have to go through ethical approval – and I think that underlying the assumptions about things like informed consent is an assumption that the researcher has power over the researched to coerce or exploit them in some way, and that therefore, the ethics procedures have to be in place in order to protect against that happening.

So I think that it would be nice to explore over the coming days what those theories of power are in research practises that we’re all involved in and how we might destabilise or unsettle them. Are there, for example, ways of using power differently or thinking about power differently in a way that enables different kinds of practises in terms of what Cove refers to as testimony-based research or advocacy? And that’s a tricky term as well. None of these terms are straightforward.

So to finish, then, a few thoughts on what empowering research might be. It’s not a term that’s used very much, if you look through the literature. So it’s been used a bit, but not very much. But Davis defines it here about sharing power. I think that’s the main thing that Davis’ definition brings through here.

I think that there is something about data-gathering no longer being a process of extraction. So if you extract data, and there is no continuity, no sort of relationship continuity, then what does that imply? It is characterised by self-reflection, reflexivity, that kind of questioning.

And I suppose the thing that I’ll leave you with as a thought is to come back to this idea of mastery and to contrast it with uncertainty. And this is something from feminist scholarship that I’ve been quite interested in. What does it mean to just allow the fact that we might not know? Radical though that is, and perhaps challenging for our careers but in terms of thinking differently about knowledge. And I think that there’s a similar, sort of binarism between the shift from sameness to alterity, sameness to otherness. So those were two thoughts that I had about what it might actually mean. But I think this uncertainty one is quite important.

After you have written your answer, make sure that you save your response. At the end of the course you will be able to export your learning diary responses in a PDF document as a record of your learning on the course by clicking on ‘Download your answers for the documents on this course’ in the left-hand column of this website.

We recommend that you keep notes of your answers to these questions so you can return to them during the course.

To understand empowerment in research we need to think about

It must be emphasised, however, that the approach taken in this course is not focused on teaching such techniques, as we think this can encourage an overly rigid and prescriptive approach to organisational research, that encourages rule-following. Instead, the aim is to empower you to develop a more imaginative research practice. Hence, the methods used in empowering research are seen as inherently improvisational, learned through skilled practice and sensory attentiveness to one’s surroundings.

How we go about producing knowledge of organisations also depends on what we understand organisations to be. Organisational research is founded on

Taken together, ontological and epistemological considerations and methods constitute a

Stories from the field

Avilasa Sengupta: entering the research field

Entering the research

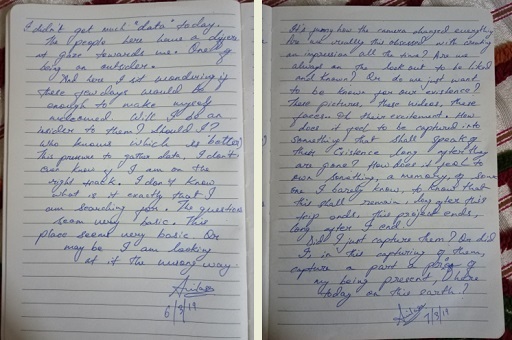

Avilasa Sengupta, a researcher on the Project Team, shows her thoughts and questioning of herself during the first two days of her fieldwork. Avilasa researched a non-profit organisation in India that seeks to recognise the Rights of Mother Earth by challenging corporate exploitation and control of natural resources, and promoting local food sovereignty and sustainable agricultural practices. The organisation works with indigenous people, farmers and women. The study focused on the practices used by the organisation to empower women and the religious/spiritual beliefs that they are based on. Here are two extracts from Avilasa’s research diary:

6 March 2019

I did not get much ‘data’ today. The people here have a different gaze towards me. One of being an outsider.

And here I sit wondering if these few days would be enough to make myself welcomed by them. Will I be an insider to them? Or should I? Who knows what is better? This pressure to gather data – I don’t even know if I am on the right track. I don’t know what is it exactly that I am searching for. My questions seem very basic, and this place seems very basic. Or maybe I am looking at it the wrong way.

7 March 2019

It is funny how the camera changed everything. Are we really this obsessed with creating an impression all the time? Are we always on the lookout to be liked and known? Or do we just want to be known for our existence?

These pictures, these videos, these faces – oh, their excitement! How does it feel to be captured into something that shall speak of their existence long after they are gone? How does it feel to own something, a memory, of someone I barely know – to know that this shall remain long after this trip ends, this project ends, long after I end?

Did I just capture them? Or did I – in this capturing of them – capture a part, a proof of my being present here today on this Earth?

Activity

Avilasa’s diary

Read Avilasa’s research diary and make your own notes in response to the following questions:

- What do you think Avilasa’s main concerns were?

- How do you think she felt as she began her research?

- How would you feel if you were in Avilasa’s position?

We recommend that you keep notes of your answers to these questions so you can return to them during the course.

Comment

Avilasa was well-prepared before entering the field. She had discussed this with her mentor who was an experienced academic and had prepared an interview guide. However, Avilasa’s diary entries reveal her uncertain feelings about ‘fitting in’, ‘being out of place’ and ‘belonging’. These are common dilemmas that confront many researchers.

You may have noticed in the first diary extract that Avilasa is concerned about how she is seen by other people and how she sees them. From the second extract, you may have inferred that Avilasa took her camera with her. She noticed how that changed how she related to participants and vice versa, and she asked herself about what ‘capturing’ people’s images could mean. Avilasa’s notes to herself reveal how she tries to think through her beliefs, values, assumptions and techniques in an ethical way. Practising empowering methodology means continually reflecting on one’s motives, personal ethics and the potential consequences of methodological choices, such as photographing participants. Photographic methods are discussed later in Section 7.

Avilasa’s self-questioning in her research diary offers a means of reflecting on her encounters and recording her thoughts in ways which she might not have felt able to do in conversation with others. This