Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 February 2026, 11:13 AM

Working together to build a community of support

Introduction

Parents are key to developing a community of support. You need to work in partnership with parents, who will be expert on their children – even if they may feel uncertain. You will explore ways of working with parents caring for children with additional support needs (ASN) and examine the possible effects of being given a diagnosis and accessing specialist support. Although it is not necessary to have a diagnosis when responding to children with ASN. You may be working alongside other professionals and drawing on a range of expertise or practical resources to provide support for a child.

Every child and every parent is unique and you need to be open to where each relationship will take you. What you learn from parents, and your developing knowledge of their child, will influence what resources and support you seek, whether they are within your setting, local authority, health board, voluntary sector or from the wider community. Together you will be building a community of support.

In Week 4 you will explore how to work with parents in caring for children, focusing on transitions and communication. You will reflect on the experience of seeking specialist support and gaining a diagnosis. You will consider the varied ways in which an early years practitioner can gain help from national and local initiatives. Early years settings are part of communities.

The content of Week 4 links to module learning outcomes (LO) 3 and 4:

- LO3 Explain the need for all staff to take responsibility to support children with ASN (not just those with specialist training).

- LO4 Be aware of the sources of support for ELC staff working with children who need additional support.

By the end of Week 4 you will be able to:

- explain the need for all staff to take responsibility to support children with ASN (not just those with specialist training)

- be aware of the sources of support for ELC staff working with children with ASN.

Continue to 4.1 Building relationships.

4.1 Building relationships

In Week 2 you heard a parent and key worker (or person) talking together about their shared care for a child. Positive relationships between staff and parents make it easier to provide the right support for all children. Developing a positive relationship from the outset can be supported by adopting a flexible and responsive approach.

Most settings have a system of key workers who have a responsibility for developing relationships with children and families. These key staff can be particularly important for children and parents as they start in a new setting. They may become less important over time as children develop their relationships with adults and may make their own choice about who to seek for comfort or support.

The

Activity 4.1 Building relationships to support transition

Read these parents’ accounts of what they found positive about support they received as their child started at a nursery. What was most important to these parents?

‘Having her [key person] come out to the flat was absolutely fantastic – I am convinced that this was a really important part of him coming to understand that he is safe and secure enough to be able to enjoy the environment at the nursery.’

‘Our experience of transition has been one where we have felt fully informed and supported and have very much appreciated the incredibly sensitive, flexible and creative approach which you and [staff member] have taken with George, who we know has been a trickier customer than most.’

‘Marie [staff member] was also good at ensuring that Lewis got to know and spend time with other staff members – particularly Dave [staff member] in the early days, which really helped on the days when Marie [staff member] was in late or not working.’

‘We very much enjoyed having Sian and Lee [both staff] to visit at home before Chloe started and it certainly made a huge difference to Chloe when she began attending the nursery, as she immediately had some “special people” who she knew she could go to. It was also extremely valuable to me to have a chance to get to know the nursery’s key workers and get a feeling for how they would interact with her.

‘The visits never felt rushed, and Sian and Lee took care to take on board the information I gave them about Chloe and to get to know her as an individual, which was reassuring for me. I love that I was able to experience the space and the daily routines like this before leaving Chloe, and I felt that she was fully ready to be left there when it was time for her to start.’

Discussion

Important points raised by parents included:

- staff being flexible and developing bespoke ways of supporting children

- arranging home visits to build relationships with parents and children

- ensuring that other staff build relationships with children early on so that if staff are absent, there are other staff available who know the child

- being able to see the setting and knowing their child’s routine

- being able to access their children’s experiences via an online communication method.

It is interesting to note that one parent perceived that their child needed more support than others to settle in, referring to ‘a trickier customer than most’. It’s important to be aware that parents might be very conscious of their child’s difference to their peers, and may perceive difference negatively – or perhaps worry that they are causing extra work or difficulty.

Having a flexible settling in place that can accommodate all children is important for all parents and children to feel included. It is also important to provide reassurance to parents and children that it is the responsibility of staff to meet each child’s needs and that it is each child’s right to have these needs met.

The comments in the activity above came from a parent survey to explore the role of key workers and to inform the nursery’s approach to supporting transitions.

However, please remember that it may not be usual practice for an ELC practitioner to carry out a home visit. Occasionally home visits may be necessary, but it is important to remember that a risk assessment should be carried out. Where possible, parents should be encouraged to come into the nursery.

Perhaps you could ask parents in your setting for their views on supporting transitions and use what you find to develop your practice?

Next you’ll look at building and respecting identity, and how and when a diagnosis can be helpful.

4.2 Working together: diagnosing disability or identifying a need

I call you out for refusing to acknowledge

sign language in classrooms, for assessing

deaf students on what they can’t say

instead of what they can

As practitioners focusing on how best to provide support for each individual child, we may need to ask for advice and input from health professionals or social workers with specialist knowledge. We need to do this with care, knowing that the way we seek support has influence over how parents and children see themselves and construct their identity. Sometimes a diagnosis can be regarded as a label and can provoke negative emotions. However for some people, knowing that there is a cause or reason for certain behaviours, and that there is a condition that can be diagnosed, can be viewed as being positive. It is very important to be aware that ELC practitioners do not diagnose conditions, though.

Activity 4.2 Reflection on diagnosing disability or identifying a need

First listen to play worker Max Alexander, who has been diagnosed as having autism, as he discusses how he views his diagnosis as a tool.

Transcript: Video 4.1 Diagnosis as a tool

Now listen to a parent’s reaction to their son’s diagnosis of autism.

Transcript: Video 4.2 Parents reaction to diagnosis

Consider your reactions to these two perspectives. Perhaps you have your own experiences of disability? Perhaps you have an additional learning need, such as dyslexia?

How might you feel about the diagnosis of a disability or identification of an ASN? Is your reaction neutral? Make a note in your learning journal of your reaction and how your reflection might influence your practice.

Discussion

Max viewed his diagnosis as something that was welcome; he called the diagnosis a tool. This can be interpreted as meaning that he could understand himself better. Also, the diagnosis meant that further support could be accessed.

The mum in the second clip was relieved that autism was the cause of her son’s difference. It appears that the diagnosis brought her a sense of relief because she had felt guilty that she had done something wrong.

What you focus on is what grows

The European Commission working group on Early Childhood Education and Care describes each child as:

A unique and a competent and active learner whose potential needs to be encouraged and supported. Each child is a curious, capable and intelligent individual. The child is a co-creator of knowledge who needs and wants interaction with other children and adults.

The above statement refers to all children. If this is our understanding of each child, then it follows that we focus on their uniqueness, their curiosity and capability, and their desire to interact with other children and adults in whatever way that might be. Curiosity, capability and intelligence will flourish if we pay attention to them. It is also important that we appreciate the strengths and opportunities that a child who requires additional support can bring to the setting.

Practitioners need to model this approach. You can build a positive relationship with a family by demonstrating your understanding of their child and your wish to get to know them and to co-create knowledge with them. This will be apparent through your interactions with children and how you document their learning through personal learning plans, online e-journals or other material and methods relevant to your setting.

One practical example is to ensure that conversations led by adults, including parents, always involve and connect with children so that children are not talked about while they are present as if they are not able to hear and understand.

Moving your body to the child’s height, bringing them into the conversation and redirecting an adult’s questions or comments to the child for their response or to acknowledge their involvement can remind other adults of the child’s agency, their humanity and their right to be involved in decisions affecting them. This approach reflects the aims of Article 12 in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Follow this link to Children and Young People’s Commissioner Scotland (2019) for further information about children’s rights and how they are addressed in Scotland.

Using wellbeing indicators

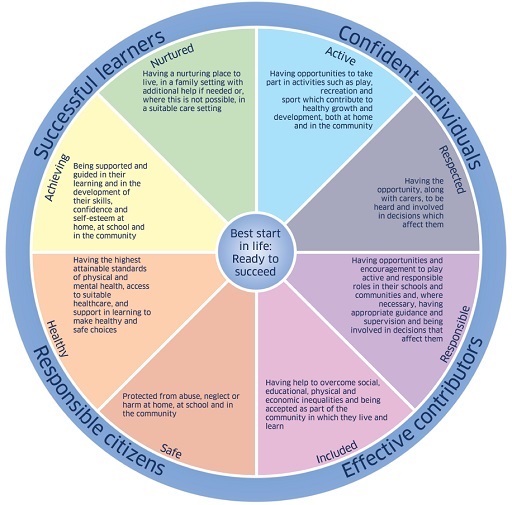

You may be familiar with the wellbeing indicators outlined by the policy ‘Getting it Right for Every Child’ (GIRFEC). You can read more about these online here:

GIRFEC includes wellbeing indicators, illustrated in Figure 4.4. These indicators can help you think about the different influences on a child’s wellbeing and help you think about how you might need to support a child or involve other professionals. You might find it helpful to have a list of the wellbeing indicators to hand while you complete Activity 4.3.

Activity 4.3 Using observations and communication to support a health concern

This activity asks you to think about the help Arianna might need for her eyesight, and about how you would ensure this help is sought.

Read the following scenario, then choose which option you think is the best approach to take.

Arianna, who is three, is very adept at using her whole body to explore an environment. She often climbs and rolls on surfaces, both indoors and outside. You have noticed that she has bumped into other children a few times recently and seems more physically cautious than usual. Arianna seems to be taking more time to approach new physical challenges.

You wonder if this is because Arianna is growing and is adapting to her longer limbs. You have noticed other children having to learn how to coordinate their changing body. However, you have noticed that Arianna’s eyes sometimes move independently, with one eye focusing inwards. You wonder whether Arianna’s vision is affecting her movement. You discuss this with a colleague, who thinks that Arianna might have a squint and should see an optician. You don’t know whether Arianna’s parents have noticed, and you decide to speak to them.

- When do you think would be the best time to speak to Arianna’s parents?

a.At the beginning of the day or at the end-of-day pick-up.

Comment

Parents (and staff) will be busy and have their own agenda, such as catching a bus or getting to work. They may not be in a frame of mind to discuss a sensitive issue. Conversations will be public if you are in the main space. All children will be present and may be listening in to a sensitive issue. However, you could use this contact time to ask for a conversation. Perhaps you could ask when it would be a good time to call?

b.At a specific pre-agreed time during the day.

Comment

You could agree a specific time to speak in advance by phone call, a quick chat at pick up or by email. You could discuss the matter on the phone but agree a time to call. A parent should have the opportunity to ensure they are in a private space to discuss their child on the phone and if you are calling them at work this might not be possible.

Where do you think you should have a conversation?

- a.In a corridor or the main nursery space.

Comment

These are public spaces and not confidential. Other children and adults will be listening. This is not private or dignified, and there is also likely to be noise and distraction.

b.In a private room.

Comment

This is preferable, and better still with the chance to make a cup of tea. Try to create a friendly family room that hosts positive experiences as well as potentially difficult conversations. Think about the layout and decoration. You’d like to create a calm, positive and welcoming atmosphere in the space you create before you even start to talk. You could speak on the phone, but you need to be in a private room to do this too.

How might you prepare for this conversation?

Comment

Review the wellbeing indicators above and makes some notes in your reflective journal about what kind of information you might need and how you might raise your concerns. You might consider the comments in Section 4.2 and the importance of neutrality in your approach. You may need to consider whether the parent has communication needs.

What did you decide?

Discussion

Perhaps you considered these points?

You might refer to your notes on observing Arianna’s physical confidence and her enjoyment of exploring her space with her whole body. The context for your observation is your understanding of her enthusiasm and confidence in physical activity.

Look up information about eyesight and the importance of intervening early. Don’t presume to diagnose a squint, but have information available about the importance of eye checks.

Start by talking about what you and parents both know about Arianna’s physical abilities and coordination, and then share your concern that her eyesight might be hindering her.

Focus on Arianna’s capabilities. You may have noticed that she is finding ways to manage the challenges of her eyesight, perhaps taking longer to assess how to move about in a space. Arianna is adapting to the challenge she is facing so she may not be upset or even really notice what is different. You do not know what will be revealed through an eye check, but you can help focus on Arianna’s competence and active learning, which will support her and her parents through diagnosis of any medical condition.

Share the information you have found about eyesight, stressing that you are not the expert but that she might need support for her vision now. Make suggestions for action such as visiting an optician, GP or health visitor.

Follow up the conversation and ask parents to let you know what the outcome is and find out if there is any action you might need to take. Remember if parents do not follow up on your suggestion of getting a professional’s opinion, you may need to talk to the child’s health visitor about the need for an eye check. Before doing so it will be important to check guidelines on information-sharing when there is a welfare concern (as opposed to a child protection concern), then parental permission will be needed to discuss this with a health visitor.

If you need to share information with another professional, such as a health visitor, practitioners should take families’ views into account and be clear about:

– what information they propose to share to support wellbeing

– who it will be shared with and why.

Families have no obligation to accept help offered to support wellbeing. However, if a child is considered to be at risk of significant harm, then information may be shared without consent and immediately.

Assessing Arianna’s wellbeing

A practitioner concerned about a child’s eye health is already using the health wellbeing indicator. They might also consider Arianna’s more cautious approach to being active and be aware of the potential for a loss of confidence as she struggles to take on physical challenges that were previously easy for her. This means considering the ‘Active’ and ‘Achieving’ wellbeing indicators.

The practitioner respects Arianna’s experience and her approach, and notices not just the difficulties that Arianna is experiencing, but also how she manages to deal with them and how she is flexible and thoughtful in adapting her body.

Arianna may need support with her eyesight, and it is important that this is addressed. It is important to draw attention to the way that Arianna manages to deal with her challenging eyesight and find new ways to assess risk or perceive distance. What will be helpful is discussing the issue with Arianna herself so that she feels respected, another wellbeing indicator. Arianna is a unique, competent and active learner, not a child with an eye problem.

The example of the concern about Arianna’s eyesight provides you with an approach that you might find helpful when faced with other concerns.

The following section explores ways that you can build a community of support to help you and colleagues in your setting to work effectively together for children with ASN.

4.3 Identifying and building a community of support

As the previous activity shows, early years practitioners need to know how and when to discuss with parents the need to involve other professionals in providing care for their child. This is everyone’s responsibility. A helpful factsheet is available on the Enquire website.

Sometimes it is clear who needs to provide help; at other times it may not be. You might need to contact a health visitor or an educational psychologist. You might need to consult with colleagues or professionals in your local authority to gain advice on the best approach. Team working is an essential part of working with young children.

Perhaps you feel you need to improve your understanding of children’s development. There are links at the end of this week’s study that you can follow to extend your learning.

If you have a concern, try to take a neutral approach. Be curious. Use the wellbeing indicators outlined in the previous section to make some notes connected to observations over time. This will help you notice ways in which the child you may be concerned about is managing their situation. It will help you see what you can build on, remembering that what you focus on is what grows. It will also help you share information respectfully with others.

One way of finding support can be from your wider community. Consider how well connected you and your colleagues are to the services in the locality of your setting.

Activity 4.4 Support available in the community

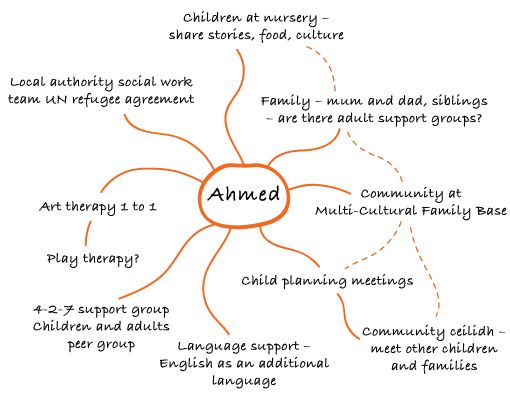

Emma Watt works for Multi-Cultural Family Base, a voluntary agency working across Edinburgh with strong connections to local nurseries and schools. Here Emma describes the support provided for a child who was a refugee from Syria and now lives in Scotland. This example illustrates the range of support that resulted from being part of a well-connected community.

While you watch the film, consider who was involved in providing support for Ahmed. Think about the different individuals and organisations that provided help.

Transcript: Video 4.3 Emma Watt – Multi-Cultural Family Base

Comment

Perhaps you noted these sources of support?

- the UN programme that organised the family’s resettlement

- His family

- nursery and school staff (practitioners, headteacher)

- nursery children

- Multi-Cultural Family Base

- 4-2-7 project worker and other children in the group

- art therapist

- social workers

- wider multicultural community – children and parents attending the Ceilidh.

It can help to map the support for a child and think about what the gaps might be, what your questions are and what you can do to strengthen support. It can help you see how the support available contributes to a child’s wellbeing. Making connections to wellbeing indicators will help you put together a Child’s Plan, which you’ll look at in Week 5.

You can try drawing a map of support in the extension activity at the end of the week.

4.4 Watching, listening and learning

In the examples in Section 4.3 you have learned about the needs of children who are recovering from specific experiences such as the trauma of war, as well as a visual impairment and an ongoing condition, Down’s syndrome. You will see that there is a need to have knowledge of the experiences and conditions in order to be able to respond to the needs of each child. It is important to be able to recognise their agency, competence and unique way of making sense of the world.

Activity 4.5 Working with Darren

Listen to Elizabeth Henderson describing an experience working with Darren, a young child who had been labelled as violent. This is an account of something that happened many years ago. Reviewing this, Elizabeth reflects deeply on her experience of supporting him.

Transcript: Video 4.4 Working with Darren

Discussion

I am respected and treated with dignity as an individual.

Elizabeth talks about respecting Darren by focusing on the gifts he brings. She looks to understand his experiences and make connections to his behaviour. She treats him as a complex individual responding to a difficult situation. She sees his distress.

I feel safe and I am protected from neglect, abuse or avoidable harm.

Darren has experienced being unsafe and there may be concerns about his mother’s wellbeing. Staff are aware of this and want to support him to make sense of this experience. He is able to acknowledge the difference between himself and his mum, which suggests he feels safe.

I experience warm, compassionate and nurturing care and support.

Elizabeth describes the emotional warmth and care she provides. Emotional labour is hard work.

Now listen to Elizabeth’s reflection on her response to Darren.

Transcript: Video 4.5 Reflection on response

Take time to consider your emotions. Being able to provide nurturing care that is warm and compassionate is hard work. You need to consider your own wellbeing. Consider the safety advice on a flight: make sure your breathing device is fitted before you help a child! To provide the right care for children, you need to care for yourself too.

You can learn more from Elizabeth Henderson by watching a longer interview.

Transcript: Video 4.6 Elizabeth Henderson – Extended interview

Perhaps there is a child you would like to seek extra help for in your setting? Why not try to map out potential support networks for a child you are working with? What are the gaps? What do you need to find out more about? What networks do you need to build? What are the strengths you can focus on?

If you are a Lead Professional, you may want to look in more depth at your role in relation to working with children with ASN. If so, please look at the extension activity at the end of this session.

Summary

This week you have explored how to build a community of support for children. You have considered how to ensure well-supported transitions to create positive relationships with parents. You have looked at a range of conditions that require additional support, including autism, visual impairment, trauma and having Down’s syndrome. This has enabled you to become aware of the range of external support available from online resources, health visitors and specialist organisations.

Reflection activity

Use your saved learner journal to make notes about this week’s content and consider how it can positively impact your practice to improve the experience for children with ASN. (You can also type into the box below, and then copy and paste it into your learner journal.)

After making notes, remember to save your learner journal to use again for the remainder of the module.

Reflection table for Week 4

| Source of knowledge | |

| Key point | |

| How has this made me think? | |

| So what have I learned? | |

| Next steps: what can I improve or what more do I need to know? | |

| Next steps: what improvements can I make to my practice? |

(Adapted from Appleby and Hanson, 2017)

Next week

In Week 5 you will look at the experience of children with complex needs.

Now have a go at the Week 4 practice quiz.

Extension activity

Extension activity – Working with children with ASN

The content in Section 4.3 discussed the importance of gaining support from a wider community. This can be about making use of your local landscape, such as finding support from your library, using an outdoor space or requesting help from a social worker or a health specialist. You may need to work in partnership with a range of professionals, as well as with parents and an extended family.

Think of a child in your setting, or simply think about your setting. How is it connected to the local community? Are there people or organisations it would help to get to know? Other adults in your community may be aware of children and families in need of extra support who perhaps you aren’t aware of.

Draw a map with your setting, or a particular child, at the centre. Think about local charities, religious communities, shops, food banks, leisure centres, parks, libraries. Who is in your community and how are you working alongside them to support children and families in your care? If you understand and have a relationship with local services, you’ll be better placed to direct families to extra support.

You will not always know what to do. There may be times where you are uncertain of your role. Being uncertain is a common experience of working with young children and is something to be valued.

Read how early years professional and academic Elizabeth Henderson (2017, pp. 81–2) describes the experience of working with children with a range of ASN:

My encounters with Marcus, Rachel and Rashid stripped back my humanity to its core making me challenge my assumptions and my ‘un/conscious ideals around normality’ (Goodley, 2014, p. 85). Often I felt uncertain about what to do, how to help them and how to understand them, while experiencing my own frailties and anxieties about my in/competence. So I did what I do best and I watched, attuning myself to their world and listened daily. On a continuous basis they humbled me as I witnessed them trying to make sense of their world, my world, our world. Consequently, their gift was to make me a far better human being for, as I journeyed with them I watched in awe of their courage and tenacity to simply be in an ever hardening, excluding world. Slowly they revolutionised my world, from the margins, inside; they were my teachers.

Our job as early years practitioners is to listen and think, and be prepared to have our worlds challenged. Early years work at its best is hard work!