Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 26 February 2026, 9:18 AM

Unit 20: Standardisation of Scots

Introduction

In this unit you will learn about what a standard language actually is, and why there is no single Standard English. In Scotland, the spoken form of English is known as Scottish Standard English (SSE). This unit will go into detail on the shift in language use in Scotland, how SSE emerged and gained precedence, how spoken Scots – widely used to this day – has no popularly agreed standard, and where that places Scots speakers and writers currently in the Scottish languages landscape.

As written communication in Scotland has been primarily carried out in Standard English for a number of centuries, Scots has become increasingly conceptualised in terms of its dialects. Since the 1920s, a range of pan dialectical grammars and standardisation suggestions have been written, which encapsulate Scots with a variety of priorities, but none have been adopted – officially or unofficially.

At the end of the 20th century, digital communication emerged with written Scots being ubiquitous in emails and online conversations, to the extent that written and spoken Scots are part of most Scots speakers’ daily media diet. This is being heralded as a new resurgence of the language, being aired in public in a way heretofore unseen. There has not been developed a standard for this kind of written output, we see that it employs a mixture of traditional spellings and phonetic spellings using English spelling conventions, as well as a mixture of standard English grammar and intuited Scots grammar.

This unit will not only summarise and discuss the history of various attempts to standardise Scots but will also give examples of Scots words and sounds for you to explore as your understanding develops.

Important details to take notes on throughout this section:

- Pan-dialectical spelling is possible

- Standardisation is more than spelling

- Written Scots is only part of the use of the language.

Activity 1

Before commencing your study of this unit, you may wish to jot down some thoughts on the four important details we suggest you take notes on throughout this unit. You could write down what you already know about each of these four points, as well as any assumption or question you might have.

20. Introductory handsel

A Scots word and example sentence to learn:

Definition: as English “School”

n., v. Also sc(h)uil, scule, skule, scöl, skuil, skeul (Ork.); shool; skill; s(c)kweel,squeel (ne.Sc.); scheel, skeel (nn.Sc.). [I., m. and s.Sc. skøl, skyl, skjyl, skɪl; ne.Sc. skwil; nn.Sc. skil]

Example sentence: “There a want o guid Scots gettin lairnt at the scule the day.”

English translation: “There is a lack of proper Scots being taught in schools today.”

Activity 2

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

There a want o guid Scots gettin lairnt at the scule the day.

Model

There a want o guid Scots gettin lairnt at the scule the day.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word.

Related word:

Definition: as English “hand”

n., v. Also haun(d), haand (Sh.), han(n) (Ork., n. and sm.Sc., Uls.), hon (Bch. coast 1891 Trans. Bch. Field Club II. 12). Sc. forms and usages of Eng. hand.

Activity 3

Click to hear the word Hand read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Transcript

Listen

Hand

Model

Hand

Example sentence: “She near hand bearit the gree at ilkane her clesses at the scule.”

English translation: “She almost won the prize in every subject in school.”

Activity 4

Click to hear the sentence above read by a Scots speaker.

You can then make your own recording and play it back to check your pronunciation.

Go to the Dictionary of the Scots Language for a full definition of the word.

Transcript

Listen

She near hand bearit the gree at ilkane her clesses at the scule.

Model

She near hand bearit the gree at ilkane her clesses at the scule.

20.1 What is a ‘standard language’?

Activity 5

The text in this section focuses on how a standard of Scots could be defined. As Scots is closely related to the English language, standardisation of Scots centres in part on the differences between Standard English and a proposed standard of Scots.

To get you thinking about this, we have recorded a number of words for you that look similar in Scots and English, but the pronunciation of these words is different in both languages.

Part 1

Listen to the recording and take a note of the words you think you are hearing and their English translation. Then compare your list with ours in the answer.

| Scots | English |

|---|---|

Answer

Here are the words you should have written:

| Scots | English |

|---|---|

| hunner | hundred |

| grund / gr(o)un / groond | ground |

| found | found |

| en / end | end |

| sound / soond | sound |

| pound / poun / pownd | pond |

| poond / pund / pun / poon | pound |

Note that there are different spellings of these words in Scots. We have selected one spelling for the purposes of this transcript.

Transcript

Listen

hunner gr(o)un found en soond pound poon

Model

hunner gr(o)un found en soond pound poon

A standard language is a form of a language that has been generally agreed upon for public use. This may conform to a dialect of a particular prestige or be a form, which accommodates various language varieties. There is no single Standard English, with different Anglophone nations maintaining English slightly differently. Yet the variations maintained in the conventions are vanishingly small in comparison with the agreement.

When considering standard languages, we can often become quite bibliocentric, becoming focused on the written form of a language, sometimes to the complete exclusion of the spoken language. This is understandable given one can point at the written word and discuss it objectively, whilst the spoken word is objectively a series of utterances which ordinarily vanish as soon as they appear.

In the context of English, we generally consider Standard English to be the written form of English based upon the spoken form of English used in London and codified in the 17th and 18th centuries. This written standard can be considered to be independent of accent.

However, a spoken standard of the English language, although not as strongly adhered to, can be conceptualised. This is most strongly associated with the Received Pronunciation accent in the UK, and outwith the UK, for example, accents such as General American, General Australian or New Dublin English.

In Scotland, the spoken form of Standard English is known as Scottish Standard English. This is the indigenous dialect of English as spoken with a Scots accent. In idealised form, this is no different from Standard English in vocabulary and grammar, but in practice it includes influences from Scots and some innovations of its own. An often cited example would be this form used in Scotland - “amn't” for the standard non-contractable “am not”.

Scots Standard English, it must be noted, came about, at the beginning of the 18th century, through a massive concerted effort of elocution lessons taught to many groups in society and the undermining of Scots in its perception as “a very corrupt Dialect [of English]” (Hume, 1932, p. 225). Initially Scots speakers aspired to speak Standard English with an English accent. When Croker quoted Boswell stating: “I doubt, Sir, if any Scotchman ever attains to a perfect English pronunciation,” he confirmed, this aspiration proved unattainable (Croker, 1866, p. 232). This led to a situation where it became acceptable to speak English with a Scots accent.

As Standard English became the agreed form of public written communication, Scottish Standard English became the spoken language of administration and education. Yet what of Scots?

Spoken Scots has persisted to this day with, in the 2011 census, over 1.5 million people reporting they speak it and 1.9 million reporting they understood it (Scottish Government, 2010). Scots literature persisted with the written language being used in periodicals and books, from poetry and cartooning through to topical political discussion and opinion pieces in newspapers. However, in the Public Attitudes Towards the Scots Language study published by the Scottish Government in 2010, 73% rarely or never read Scots and 83% rarely or never wrote in Scots, whilst only 29% rarely or never spoke Scots. Only 3% read and 2% write in Scots 'a lot' (Webarchive.org.uk).

This study by the Scottish Government presents Scots as a widely spoken language variety whose speakers are perhaps largely illiterate in its written forms. Although, literacy in writing Scots may be growing today with the advent of micro-blogging on social media, endogenous conventions appear to be emerging with no connection to the 700 years of Scots literature prior to these written outputs online. Thus, thoughts of a standard language are intimately bound up with this increasing literacy in Scots in the 21st century.

The minority who do engage in written Scots are presented with a myriad of different approaches to writing this language: from those striving to authentically represent the spoken language of a specific area; to those using language to stereotype a speaker; and those who use the barest minimum of Scots within a largely Standard English text, to those who wish to maximise the difference between Standard English and their sub-textually proposed Standard Scots.

Sometimes a maximalist use of Scots lexicon, or vocabulary, can be so far removed from spoken Scots that it is rejected by Scots speakers. Whilst this is an exemplar of what written Scots can do, it may be argued that it is too far diverged from what written Scots ought to do.

A standard of a language facilitates the memetic communication of this language; it allows people to learn it independently of social immersion and it informs spoken performance of the language. This means, in the case of Scots, that people do speak the maximalist Scots found in the literature and people do change their Scots dialect towards more general usage of both the spoken and written word. As written Scots is increasingly used in public, it will likely level towards a consensual common form. The form this takes, and its uptake will be dependent upon its utility to its users.

Often with Scots, one develops one's literacy on one's own. A person brings their own conscious and unconscious linguistic knowledge, and prejudices to some sort of body of written Scots and finds an expressive solution that satisfies their needs. An agreed standard for public usage need not conflict with this level of engagement with one's own expressive writing. However, a standard worth advocating for ought to draw on as much knowledge about spoken and written Scots as possible.

From here onwards, you will explore some of the issues to do with coming towards a standard form of written Scots touching upon traditional written conventions, dialect variation, pan dialectical spelling and grammar. And once you have explored these aspects, you’ll look more deeply into the shift in language use in Scotland and the emergence of Scottish Standard English. As a next step, you'll investigate what has been done thus far to standardise Scots and finally you'll touch upon language planning.

Activity 6

After reading this section, take a note of the key aspects you learned here.

Answer

This is a model answer. Your notes might be different.

- A standard language is a form of a language that has been generally agreed upon for public use.

- When considering standard languages, we can often become focused on the written form of a language, sometimes to the complete exclusion of the spoken language.

- A standard of a language allows people to learn it independently of social immersion and it informs spoken performance of the language.

- The standard of the English language is most strongly associated with the Received Pronunciation accent in the UK.

- In Scotland, the spoken form of Standard English is known as Scottish Standard English. This is the indigenous dialect of English as spoken with a Scots accent.

- Scots Standard English came about at the beginning of the 18th century through the undermining of Scots in its perception as a ‘corrupt dialect of English’.

- It became acceptable to speak English with a Scots accent.

- As Standard English became the agreed form of public written communication, Scottish Standard English became the spoken language of administration and education.

- Scots today is a widely spoken language variety whose speakers are perhaps largely illiterate in its written forms.

- Increasing literacy in Scots in the 21st century through micro-blogging on social media.

- Often with Scots, one develops one's literacy on one's own.

20.2 How could one standardise Scots?

Both English and Scots face a fundamental problem in spelling in that we use the Latin alphabet, with its 21 consonants and 5 vowels to represent 24 consonant and approximately 25 vowel sounds in received pronunciation, and 26 consonant and approximately 14 to 17 basic vowel sounds in the various Scots accents.

Vowels – spoken and written

“Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (length). They are usually voiced, and are closely involved in prosodic variation such as tone, intonation and stress.

The word vowel comes from the Latin word vocalis, meaning "vocal" (i.e. relating to the voice). In English, the word vowel is commonly used to refer both to vowel sounds and to the written symbols that represent them.” (Wikipedia)

- A written vowel is a, e, i, o, u and sometimes y.

- A spoken vowel is a sound produced with the voice where the airflow is not impeded.

We chose to give you the two specific handsel words for this unit as they, on the surface, may seem at first quite akin to Standard Scottish English. When one takes a closer look, one finds they behave quite differently from their Standard English equivalents. Before exploring standardisation of Scots, we shall delve a little deeper into these words to get a flavour of some of the issues facing us when considering such a thing as Standard Scots.

Handsel number 1: scule

There are about 6 different pronunciations and 14 different spellings of the Scots word scule. This is in addition to the English spelling 'school' and the English pronunciation, 'skool'.

Activity 7

Listen to 5 different pronunciations of scule in Scots and match the pronunciations with the different spellings of the word. Then pronounce the variations and record yourself doing so. Compare your recording with our model.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 5 items in each list.

Word in audio No. 1

Word in audio No. 2

Word in audio No. 3

Word in audio No. 4

Word in audio No. 5

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.skill

b.scule, skule

c.s(c)kweel, squeel

d.sc(h)uil, skuil

e.scheel, skeel

- 1 = a,

- 2 = b,

- 3 = c,

- 4 = e,

- 5 = d

Much of the spelling variation can be accounted for with the realisation of the hard

Often the vowel is where dialectical variation can make things interesting.

The spellings skill, scöl, skweel/squeel, skeel, and skeul represent local dialect pronunciations. The spellings scule and scuil are pan-dialectic spellings, if we learn that our local dialect pronounces words spelled with

This understanding reflects a pan-dialectical approach to spelling that allows us to use a traditional Scots spelling convention and maintain our dialectical pronunciations of a variety of words.

Activity 8

Listen to the recording of different local dialect pronunciations of the words ‘just’ and ‘moon’ in Scots, following the explanation above. Here are the words you will hear:

muin, min, meen; jest, jist, juist.

Put these words in the order in which they appear in the recording.

Answer

Here is the order in which these six pronunciations appear in the recording:

jist, min, juist, muin, jest, meen

Use of ‘the’ and Standard Scots

The grammar of this handsel word can be quite consistent across dialects. Each will likely precede the word with the definite article ‘the’. In Standard English one ought not to speak of “the school” unless referring to a particular school. Let’s look at the following example in Standard English:

- Jane was old enough to go into second year at school.

The grammar in English in the sentence above begs the question, 'which school?' Whereas the same sentence in Scots:

- Jean wis big eneuch fir tae ging intae saicont yeir at the scule.

….does not beg that question, it is well attested in Scots grammar.

A question with respect to a Standard Scots would be whether the sentence

'*Jean wis big eneuch fir tae ging intae saicont yeir at scule' without the definite article, ought to be thought of as grammatically incorrect Scots. Can one say this is “bad Scots”, or even that this is not Scots?

It can be quite common in written works for an author to use Scots vocabulary yet use Standard English grammatical rules. To remove the 'the' article does sound incorrect to Scots speakers who use this grammatical feature.

We do know that the definite article is applied to words in a systematic way in Scots, which is distinct from Standard English, as has been outlined in Unit 17 on grammar. In Unit 17 you learned that Scots uses determiners such as the definite article ‘the’ more often than Standard English does, for example in ‘the college, the cauld, the Gorbals’ etc. When we observe these relatively systematic features in a language, we can extract rules to prescribe how one ought to correctly write in a language.

Handsel number 2: hand

There are four pronunciations and about five spellings of this word in Scots. The Dictionary of the Scots Language chooses the Standard English spelling as the primary headword.

The two main pronunciation categories in this word are the vowel used and the inclusion or exclusion of the 'd'. In dialects south of the Tay the vowel pronunciation tends towards the THOUGHT sound, typically spelled as

Activity 9

Listen to the two words, then record yourself pronouncing them paying attention to the variation in pronunciation. Don’t forget to compare your recording with our model.

Transcript

Listen

haun, haan

Model

haun, haan

Choosing a pan-dialectical standard spelling of this vowel in Scots would involve picking one of either convention,

There is also a variation in consonant usage in this handsel word. The exclusion of a

This can also be extended to the letter following the letter

Language links

The close links between Scots and German can not only be found in the vocabulary the two languages use, but also in the way letters, or combinations of letters are pronounced. There is a very obvious correlation when it comes to the pronunciation of the

In some Scots dialects, this is not a completely consistent rule. Some dialects would use 'hunder' for 'hunner'. Also, when the word is extended with an ending, these letters may, or may not, reappear. For example, haun becoming the word 'haunner', or in the verb meaning ‘to give’ or ‘to hand (over)’, one can have either 'haanit' or 'haandit'. Indeed, the word 'handsel' itself can be pronounced as either <haunsel> or <haandsel>.

When considering deciding upon a standard Scots spelling, we may ask: Ought we to maintain silent consonants like

These are just some of the aspects to consider when thinking about developing a Standard Scots.

Activity 10

In this activity, you will use the information you have come across in this sub-section with regard to spellings and silent consonants. Listen to the recording of five Scots words, then write these words in Standard English. Remember to practise speaking these words and comparing your pronunciation with our model.

20.3 Scots Standard English - A standard written language

In sociolinguistics it is recognised that languages have different registers, which are varieties of the language that are deployed in given social interactions. For example, if one is in a formal situation, one would communicate differently than with one's friends.

From a rhetorical perspective, considering the type of communication one is engaging in, one can consider which mode one is deploying. That is to consider, for example, are you narrating, describing, or arguing a point? Of particular interest here is expository rhetoric, which is the typical style of language used to provide explanations or information. Examples of this are traffic signs or bulletins.

When people think of the use of a standard language, they often consider only the formal register and the expository mode. Historical linguists have observed that Scots was beginning to form standard conventions where it was used in these registers and modes.

In the 17th–19th centuries formal expository text in Scotland standardised to Standard English, abandoning the written Scots used in clerical occupations for hundreds of years. Written Scots in other registers and rhetorical modes, such as letters, music, comics, poetry and quoted speech has persisted.

During this 200-year period, prescriptivism, defining how someone ought to write and speak, was the role of the linguist. It wasn't until the 20th century that descriptive linguistics, observing and understanding how people use language, came to the fore. It's with these descriptive tools we can today observe and speak about Scots language varieties and derive a prescriptive written Scots Standard.

As we have seen, it's with this prescriptivism, being told the 'correct' way to write and speak, the spoken language variety Scots Standard English came into being.

From the 18th century, labouring under the misapprehension that Scots was a corruption of pure English, initial attempts at reforming Scottish language looked to change the accents, that is the underlying phonological structure, of Scottish speakers. This ultimately proved an impossible enterprise and to this day there are still elocutionists working to 'neutralise' Scottish accents. It ought to be noted that there is no such thing as a neutral accent. Therefore, when people strive to ‘speak properly’, they aim to speak the accent of the dialect with most 'prestige'.

As such the movement to standardise towards written Standard English sought to have Scottish speakers speak Standard English, sometimes humorously referred to as 'Broad English', with the Scots phonological system, i.e. using the sounds from the Scots language to speak English. As mentioned before, today this is known as Standard Scottish English (SSE).

The creation of Scottish Standard English (SSE)

Let’s now look at how Standard English was used as a model to actively change spoken Scots into Scottish Standard English. Sometimes the reversal of this process gives a useful insight into exploring Scots and seeing how a standard written Scots might be achieved.

There is a reasonably simple algorithm to deploy, to alter one's Scots to be suitably understood as English with a Scots accent. This is often the process Scots speakers go through at school whilst learning to become literate in English. Here we consider whether these rules could be applied in the same way when developing a standard of Scots.

The basis are the cognate words, the words which sound closest between Scots and English. These are used to provide the map of which sound in Scots matches with which sounds in English. These appear in words like: bed, shoot, can.

To this day, people may think of these cognates as English words, where they are indeed both English and Scots. Some Scots sounds map to more than one Standard English sound, such as the vowel in both ‘ant’ and ‘aunt’ being the same in Scots accents whilst there are two different vowel sounds in standard English. Where Scots makes a distinction, for example between the vowels in ‘bride’ and ‘died’, this is disregarded.

Words which are cognate to English words but with phonological differences are changed in SSE to be phonologically consistent in their sound mappings. So heid becomes ‘head’, using the same vowel sound as in ‘bed’; pit becomes ‘put’, using the same vowel sound as in ‘shoot’; haun becomes ‘hand’, using the same vowel sound as in ‘can’, and with the addition of the 'd'.

Each of these two categories of words above make up roughly half of the one thousand most common English language words.

- All of these words must only represent the Standard English meanings. Words like 'away' do not, for example, mean to go in SSE. Whilst 'that's me awa' means I am leaving, 'that's me away' does not.

- All Standard English words will become part of Scots Standard English. For example, 'little' replaces 'wee' or 'smaa'; or 'why' replaces 'hou', 'whit wey' or 'whit fir'. This group of words are those which can prove highly contentious when conceptualising a standard Scots, ought we to eject these English loan words from a Standard Scots vocabulary?

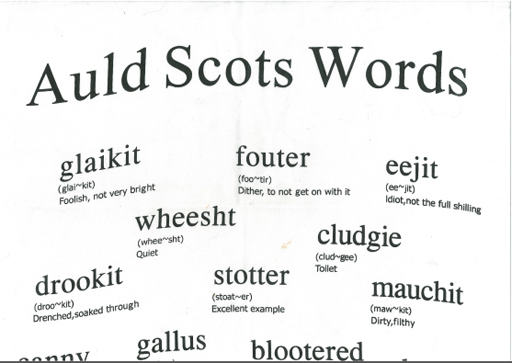

All Scots words which have no English cognates are prohibited. This later group of words, the kind one finds on tea-towels, can be what many people conceptualise as Scots, for example as shown in the image of the author’s dishcloth in Unit 2:

- All new words invented or adopted will follow the rules of Standard English. In conceptualising a Standard Scots ought we to reject neologisms such as 'vacuum cleaner' and come up with unique Scots neologisms such as 'stoor sooker'?

- All grammar will conform to Standard English grammar. For example this sentence would be considered correct: ‘Can't you tell the difference?’, as opposed to: ‘Can you not tell the difference?’ – as the second form uses the Scots grammar in sentence formation – 'Cin ye no tell the difference?'

- And as Standard Scottish English follows the conventions of Standard English, written Scottish versions of cognates shall follow Standard English conventions, for example: ‘aunty’ would be the correct form as opposed to auntie.

20.4 A Standard Scots

A brief history of Scots and its Anglicisation

“Scots is descended from a form of Anglo-Saxon, brought to the south east of what is now Scotland around AD 600 by the Angles […]. English is also descended from the language of these peoples. […] From 1494 it came to be known as 'scottis' and in this, the Stewart period, it began to develop a written standard, just at the time when the East-Midland dialect of English was becoming the basis for a written standard in Tudor England. It was the vehicle for the works of the great late-medieval makars (poets) like William Dunbar, Gavin Douglas and David Lindsay. […]

After the Scottish Reformation (1560), the Triple Monarchy (1603) and the political Union with England (1707), English gradually became the language of most formal speech and writing and Scots came to be regarded as a 'group of dialects' rather than a 'language'. It continued, however, to be the everyday medium of communication for the vast majority of Lowland Scots, and was used creatively in poetry, song and story. It reached its pinnacle of literary achievement in this period in the work of men such as Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns. […]

The number of Scots speakers probably reached its height in the course of the 19th century, but the lack of a standard, and an insistence after 1845 that children be made to speak English in the schools, often to the exclusion of Scots, did not help the situation. At present Scots is primarily a spoken language, with a number of regional varieties, each with a distinctive character of its own, and is heard widely in most parts of the country.”

Whilst the expository mode and formal registers of written Scots were quite quickly displaced with Standard English, with the notable exception of legal and political Scots words, spoken Scots Standard English would have taken longer to be established. Key enlightenment figures bemoaned the poor standard of their spoken English language whilst being celebrated literati, as the example from David Hume’s letters testifies:

“Is it not strange that, at a time when we have lost our Princes, our Parliaments, our independent Government, even the Presence of our chief Nobility, are unhappy, in our Accent & Pronunciation, speak a very corrupt Dialect of the Tongue which we make use of; is it not strange, I say, that, in these Circumstances, we shou'd really be the People most distinguish'd for Literature in Europe?” (Hume, 1932, p.255).

Spoken Scots, of course, continues to this day but with no popularly agreed standard exemplar such as Scottish Standard English towards which speakers can converge. Written Scots continued in a literary or narrative mode in prose fiction, eventually mostly residing in reported speech as you learned in Unit 19. In addition, poetry, personal letters, song, cartooning, theatre, and planned performative speech all have maintained a continuity of Scots, and also certain aspects of journalism, aspects which have featured in various units throughout this course.

Scots being conceptualised as “a very corrupt dialect [of English]” (Hume, 1932, p.255) through the period of the last 450 years led to much conscious and unconscious 'correction' of the written form, particularly in its grammar. This in turn resulted in the influence of Standard English on even avowedly Scots writing. This can be seen in the standard English grammatical words being employed widely, such as 'to' over 'tae', 'you' over 'ye'. A popular example of these developments is Burns' Scots Wha Hae, where in authentic Scots 'wha' ought to be kept only as the interrogative, and the title in more authentic Scots would read Scots Thit Hae.

And so, things continued with each generation producing writing expecting it would be for the last speakers of Scots, a sentiment which is vividly expressed in Robert Louis Stevenson's ‘The Maker to Posterity’:

“Few spak it then, an’ noo there’s nane.

My puir auld sangs lie a’ their lane,

Their sense, that aince was braw an’ plain,

Tint a’thegether,

Like runes upon a standin’ stane

Amang the heather.”

Each generation of writers noticed and documented the generational changes down to language shift, yet perhaps did not detect the extent to which the Scots language was continuing to be transmitted and to innovate. The fear of losing the Scots language, as for example expressed by Stevenson, has been met with various revivalist movements, often with much support coming from those most removed from the spoken language. This includes the work of Allan Ramsay in the 17th-18th century, of Robert Burns in the second half of the 18th century, of Scott and Hogg into the 19th century, and of Robert Louis Stevenson towards the 20th century, as well as of Violet Jacob into the 20th century.

Then, there was the literary movement the Scots Renaissance from the early to the mid-20th century, which can be conceptualised as the Scottish version of modernism. One observation is that with a constant look to revivalism written Scots and spoken Scots began to diverge. This is a particular ‘accusation’ levelled at the Lallans movement and the “synthetic Scots” championed by Hugh MacDiarmid. This “synthetic” style of written Scots allows words and linguistic features to flow across constraints of time and geographical location within the literature. “Synthetic” in this context meaning a bringing together, and here it is unfortunate that the word “synthetic” took on the artificial connotations of the products of the late 20th century petrochemical industry with added many negative connotations.

With national communication primarily being carried out in written Standard English, Scots became conceptualised in terms of its dialects. It wasn't until the invention of broadcast media that spoken Standard Scottish English or Standard English entered the home, although the reach of schools and universities had already extended there for quite some time. Famously, Lord Reith as director general of the BBC established a spoken standard for public broadcast which sought to eradicate local varieties. The 20th century also saw the rise of improvisational speech in telephony and radio communication.

During the late 20th century prescriptive grammars very much fell out of favour world wide, and whilst figures in the Scottish cultural Renaissance produced significant works of international importance in literary Scots, popular works tended to be in Scots viewed as a dialect of English, neither working towards nor seeking a standard form.

With these new technologies came new rhetorical modes, registers and conventions of speech, and Scots language has very much been a part of that. At the end of the 20th century digital communication has emerged with written Scots being ubiquitous in email, SMS messaging, message boards, chat rooms, and websites; and now with the new social media platforms micro-blogging, online newspapers, e-books, podcasting & vlogging, written and spoken Scots is part of most Scots speakers’ daily media diet. This is being heralded as a new resurgence of the language, being aired in public in a way heretofore unseen.

There has been no standard for this kind of written work, most people being autodidacts, and thus it employs a mixture of traditional spellings and phonetic spellings, using English spelling conventions, and a mixture of standard English grammar and intuited Scots grammar. The use of Scots language in social media is being more and more recognised. This can be seen, for example, in the fact that Twitter established a Scottish Twitter visitor centre as part of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2019. This exhibition reflects that many consider

“Scottish Twitter […as] arguably the nation's finest export, and largely consists of sweary jokes in Scots that are shared online, mainly on the r/ScottishPeopleTwitter subreddit. Scottish Twitter came to prominence after BuzzFeed UK's Luke Bailey spent about a year collecting weird tweets, which he then unleashed upon the world in August 2015 in an article titled "35 Reasons Scottish Twitter Is The Wildest Place On The Internet.”

This initiative reflects what you learned about in various units, namely that often Scots is used for and cherished as a medium to express humour. An example is the winning tweet of the 2019 exhibition by @marcsimps0n:

“wis walkin home n someone threw a block of cheese oot their windee n it hit me on the head, i turned n shouted that wisna very mature wis it”

Yet Scots is not only used to express humour in social media online. The Scots Language Forum group on Facebook with over 5400 members, is an example of social media use that goes far beyond the Twitter example above. This group shares resources, information on events and interestingly discusses the use of Scots language and meaning of Scots vocabulary in context in the different dialect areas. People in this group write in English as well as In Scots, or a mix of both. There are more examples of such groups with a more localised focus, such as the Shetland Scots Facebook group Wir Midder Tongue started by Shetland Scots speakers. The group describe their purposes as:

“Keepin’ da Shetlan’ dialect alive bi encouragin’ fok no oanly ta spaek in wir native tongue, bit ta write in it... sharin’ stories, poems, sangs, sayin’s, guddicks... introducin’ wir dialect ta fok unfamiliar wi it…”

Activity 11

You will conclude your study of section 20.4 with this activity, in which you will engage with written Scots and written Standard English. You will be bringing together what you have learned in different units of this course here, your skills at using the DSL, understanding local varieties of Scots, the links between Scots and Standard English and the links between written and spoken Scots. For these purposes you will be working with a well-known example of poetry in the Scots language, Robert Burns’ ‘’The Deil's Awa Wi The Exciseman’ (1792). Burns, who was employed as an Exciseman himself from 1789–1796, wrote this humorous song from the perspective of a community who revel in the absence of the loathed Exciseman and defiantly reject governmental regulation that would normally be imposed by him.

Part 1

First of all, work with the spoken version of the lyrics of this song. Listen to the recording and try to follow the spoken Scots understanding the meaning of the words and the song as a whole. Then, using the transcript, read the lyrics of the song, recording yourself as you do so and compare your version with our model.

Transcript

Listen

The Deil's Awa Wi The Exciseman

The deil cam fiddlin thro the toun,

An danc'd awa wi th' Exciseman,

An ilka wife cries, "Auld Mahoun,

A weish ye luck o the prize, man."

Chorus-

The deil's awa, the deil's awa,

The deil's awa wi the Exciseman,

He's danc'd awa, he's danc'd awa,

He's danc'd awa wi th' Exciseman.

We'll mak oor maut, an we'll brew oor drink,

We'll laugh, sing, an rejoice, man,

An mony braw thanks tae the meikle black deil,

Thit danc'd awa wi th' Exciseman.

The deil's awa, &c.

There's threesome reels, there's foursome reels,

There's hornpipes an strathspeys, man,

But the ae best dance ere came to the laun

Wis-the deil's awa wi the Exciseman.

The deil's awa, &c.

Model

The Deil's Awa Wi The Exciseman

The deil cam fiddlin thro the toun,

An danc'd awa wi th' Exciseman,

An ilka wife cries, "Auld Mahoun,

A weish ye luck o the prize, man."

Chorus-

The deil's awa, the deil's awa,

The deil's awa wi the Exciseman,

He's danc'd awa, he's danc'd awa,

He's danc'd awa wi th' Exciseman.

We'll mak oor maut, an we'll brew oor drink,

We'll laugh, sing, an rejoice, man,

An mony braw thanks tae the meikle black deil,

Thit danc'd awa wi th' Exciseman.

The deil's awa, &c.

There's threesome reels, there's foursome reels,

There's hornpipes an strathspeys, man,

But the ae best dance ere came to the laun

Wis-the deil's awa wi the Exciseman.

The deil's awa, &c.

20.5 A Standard Scots continued

Whilst some may ask: “Can there be a Standard Scots?” enquiring if it is possible to define one, it has already been demonstrated that there can be. The question that remains to be answered is, ‘Which standard will there be?’

One consideration when answering this question may be that a standard ought to come from a prestige dialect. There have been a number of the dialects with stronger identities that have sought to define themselves quite fervently and these dialects may be candidates for being ‘prestige dialects’. But, again, we face the challenge of defining for example a standard Doric, a standard Shetland, a standard Ayrshire, or a standard Borders.

Below you will find a list of publications establishing dialectical standards in the Scots language with some leaning more towards novelty books than functional dialectical standards. Yet all are provide insights into particular varieties of Scots.

- 1866 – An Etymological Dictionary of the Shetland and Orkney Dialect, Thomas Edmunston

- 1914 – A Glossary of the Shetland Dialect, James Stout Angus

- 1915 – Lowland Scotch as Spoken in the Lower Strathearn District of Perthshire, James Wilson

- 1979 – The Shetland Dictionary, John J Graham

- 1990 – Teach Yourself Doric, Douglas Kynoch

- 1990 – Dundonian for Beginners, MickMcClusky

- 1996 – The Complete Patter, Michael Munro

- 1996 – Doric Dictionary, Douglas Kynoch

- 2007 – Ulster Scots, Philip Robinson

- 2009 – Spikkin Doric, Norman Harper

- 2013 – A Hawick Word Book, Douglas Scott

A concern amongst those who speak those dialects mentioned in the publications above, is that the dialects of Scots with less strong identities, but much larger populations, such as the urban dialects, will prevail as a standard. Indeed, the worry is that any standard form of Scots is a threat to their dialect as much as standard English has been to Scots. This is a valid concern – yet an example that shows that efforts are being made to give parity to dialect versions of Scots are recent publications of multiple versions of The Gruffalo and Alice in Wonderland in different Scots dialects. Developments like these allow for a better reflection of dialect speakers’ language in literature written in Scots.

Since the 1920s and increasingly in the internet age, a number of pan-dialectical grammars have been published which encapsulate Scots with a variety of priorities, some of these publications you have come across in Unit 17 of this course.

- 1921 – Manual of Modern Scots, William Grant & James Main Dixon

- 1947 – The Scots Style Sheet, The Makkars' Club

- 1979 – Recommendations for Writers in Scots, Scots Language Society

- 1996 – Mensfu Scots Spellin, Scots Spellin Comatee 1996-1998*

- 1997 – A Scots Grammar, David Purves

- 1997 – Wir Ain Tung, Andy Eagle*

- 1999 – Grammar Broonie, Susan Rennie (with additional material by Matthew Fitt)

- 2002 – Luath Scots Learner, L Colin Wilson

- 2009 – Scots language Wikipedia style guide*

- 2012 – Modren Scots Grammar, Christine Robinson

- 2013 – The Scots Learners' Grammar, Clive P L Young*

- 2014 – Aw Ae Wey, Andy Eagle*

- 2014 – Mind yer Language, Michael Dempster*

- 2016 – An Introduction to Modern Scots, Andy Eagle*

- 2017 – Mak Forrit Stylesheet, Jamie Smith*

- *self-published and available online.

In the publications of this list above, the Style Sheets and the Scots Spelling Comatee's recommendations aim at regularising literary Scots. Andy Eagle in his publications looks for a pan-dialectical written standard, moving away from phonological representation of phonetic spelling. Colin Wilson’s objective is to introduce Scots to new learners. Susan Rennie and Christine Robinson look to provide accessible grammars for children and adults seeking to become literate in Scots. Michael Dempster’s work looks to teach speakers, singers and performers how to understand written Scots' connection to spoken Scots as it is across dialects and historical periods.

The author of this unit’s own preference is for a Standard Written Scots that can capture as much as is spoken today, particularly with grammatical veracity. Others want a single standard of prescriptive spelling that all can work to. Some believe ease of learning ought to be a priority when developing a standard for Scots. Others still feel that in the language shift towards a standard historical reconstruction ought to be a priority.

The list of criticisms often expressed about use of Scots is long, for example people criticise the use of others’ spelling agreement, or words being used that are not considered contemporary or from a speaker's dialect area, or English grammar standards superseding Scots ones in language use. However, these are all criticisms which can be hurled at any standard language. And once one takes the time to consciously address each of these issues, it becomes clear that they are far from insurmountable and rarely as big an issue as they seem. And … all of these things are teachable.

What has been absent until recently in the wider Scots community is the will to teach or learn a standard. It is likely that from those publications listed above a perfectly functional standard can be reached. Regardless of such publications, due to the possibilities for digital self-publishing and a massive new body of Scots examples and innovations, even a single text or tweet, new conventions are emerging, such as the spelling of the English ‘cannot’ in Scots as canny (previously cannae), the English ‘going to’ in Scots as gonny (previously gonnae), or the English ‘have to’ in Scots as huvty (previously huv tae).

This emergent usage represents a written connection to hundreds of years of Scottish culture. Yet this connection does not always seem to be immediately evident to those who have the desire to express themselves in their language, Scots. They sometimes struggle to know how to connect to this wealth of Scots literature. This is where we come full circle and where institutions that house collections of Scots in spoken and written form continue to reach and have an impact on Scots speakers, its writers and readers.

Activity 12

To conclude your study of this section, you will again test your translation skills and apply what you have learned here by translating the Scots instructions below into Standard English. In these instructions we have purposefully used a mix of Scots vocabulary and spellings which you have come across in various units of this course.

This time try not to reach for the DSL immediately when you are not sure about the meaning of a word. Try reading out loud the instructions first of all, which can help you understand the word, even though you might not be familiar with its particular spelling here.

“Yer gonnae huvty git oan yon bus – thae een, at’s heidin sooth – if ye ir gonny hae ony hope o makkin it doon the links afore fower a clock...”

Answer

This is our suggested translation of the Scots instructions. Your translation might be different.

“You are going to have to get on that bus – that one, that’s heading south – if you are going to have any hope of making it down to the golf course before four o clock.”

20.6 Looking ahead

You won't have to go to many Scots language events before hearing Max Weinreich's quip: “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy” (cited in Weston and Jensen, 2000, p.85). This quote links back to the discussions you were introduced to at the beginning of this course around what distinguishes a dialect from a language. In this statement Weinreich insinuates that a language is a dialect variety of that language that has the most power, and this power can take many forms, for example a government policy. Far more important is that a language variety, if it is to exist in a standard form, has a scule and a polis – meaning that key social and cultural institutions use and accept this language variety as a standard.

There have been excellent moves towards prestige planning for Scots, with the funding for, and the support of Scots language dictionaries, The Scots Language Centre, and the inclusion of Scots in the Curriculum for Excellence; and with The Scottish Book Trust, Creative Scotland, the National Library of Scotland, and many others supporting Scots as a language in its own right. Additional milestones towards this goal include the ratification of the European convention on minority languages in Scotland and the inclusion of a question on Scots in the 2011 census, with a more in-depth question planned for the 2021 census.

All these initiatives and developments are bringing spoken Scots out of its neuks to an existence in the wider public sphere where consensus may be reached upon a standard of Scots required for public discourse.

Yet, there is some way to go… Currently, supporting speakers and learners to express themselves in written Scots does require literacy in English to inform their writing. It has been left to the individual learner to develop more in-depth knowledge about traditional Scots spelling, grammatical forms that may not be immediately apparent to Scots speakers and learners, or how to access dictionaries and Scots language resources alongside developing ideas about best practice.

Often these challenges can be a barrier to literacy in the Scots language. Yet, with the emergence of publicly accessible education resources, and the underlying common store of written and spoken Scots that has become more visible through modern media, a more popular consensus is being reached on how Scots as a public language works. An agreed authoritative standard for written Scots, ratified by authoritative groups, could very well support speakers, learners and teachers in further overcoming barriers to literacy. Agreement on one spelling per word, a grammatical preference and a curriculum for teaching the language are vital components in achieving this. Part of this effort would have to be the gathering of a corpus of written work to present as best practice and core elements of a cultural heritage in the Scots language.

A majority of Scots language literature published to date goes against, in some ways or others, what may be considered best practice. One key question going forward towards a Standard Scots would therefore have to be whether these works ought to be revised for inclusion in a corpus of best practice. Comparing this approach with practice in other languages, we find that classics of historical works preceding standardisation are routinely translated into modern standard languages, such as Beowulf, or the works of Chaucer and Shakespeare in English. This is common practice in order to make the cultural heritage in a particular language accessible to modern speakers of that language. This is a result of the fact that languages are not static entities and that they constantly evolve according to the needs of the speakers through the centuries.

In this unit you have seen that much of the work to achieve a Standard Scots has already been carried out, and the knowledge attained to develop a functional Standard Written Scots that is independent of dialects. Scots is increasingly being brought into the public arena in our multilingual society and there is increasing acknowledgement of the benefits of de-stigmatising and legitimising minoritised first languages such as Scots. Perhaps we are now at a time where our increasing Scots literacy is ready to accept and utilize a Standard Written Scots.

20.7 What I have learned

Activity 13

Before finishing your work on this unit, please revisit what you worked on in Activity 1, where we asked you to take some notes on what you already knew in relation to the key learning point of the unit.

Compare your notes from before you studied this unit with what you have learned here and add to these notes as you see fit to produce a record of your learning.

Here are the key learning points again for you as a reminder:

- Pan-dialectical spelling is possible

- Standardisation is more than spelling

- Written Scots is only part of the use of the language.

20.8 Course conclusion

You have now reached the end of this course on Scots language and culture. We would like to thank you for participating in this course, where you engaged with a wide variety of artefacts in the Scots language – ranging from Medieval wills and translations of the Bible, to films and radio shows, poems, songs, cooking recipes and tweets in Scots.

We hope that you have found this course thought-provoking and that you have learned new Scots words and phrases, as well as a lot of new things about Scotland, its diverse regions, and its rich culture and history – even if you have lived in Scotland all your life.

If you were not a speaker of Scots when embarking on your study, we hope that you now feel you can understand the language when hearing and reading it, have a good grasp of Scots grammar, of the differences between Scots and English, and have even begun to speak and write in Scots yourself.

We thank our partner institution, Education Scotland, and Bruce Eunson in particular, for their outstanding collaboration on this project, without which this course would not have come to fruition.

Secondly, we express our gratitude to the authors (listed here in alphabetical order) for their rich contributions and excellent co-operation with us on this resource:

- Alan Riach

- Annie Mattheson

- Ashely Douglas

- Billy Kay

- Bruce Eunson

- Chris Robinson

- Diane Anderson

- Donald Smith

- Ged O’Brien

- Ian Brown

- James Robertson

- Liz Niven

- Matthew Fitt

- Michael Dempster

- Simon Hall

- Steve Byrne

Without their expertise, knowledge and experience this course could not have become the wide-ranging resource it is, including the images and audio recordings many of the authors contributed.

We would also like to express our thanks to Laura Green, Michael Hance, Alistair Heather, Christine De Luca and Jeremy Smith for volunteering to record audio for this course, a resource that adds much to its language learning aspect. In addition, we would like to thank our course pilot participants for their invaluable feedback.

Finally, we would like to thank Sylvia Warnecke for all her inspiring work on the development of the educational course design for teaching Scots on the course, as well as authoring the Introductions to parts 1 and 2 and many of the activities on the course.

What next?

Badge

If you are interested in gaining a digital badge as proof of your successful study, you can now take our course quiz, which tests your knowledge with 14 questions. You have unlimited attempts to achieve a pass grade of 60%, after which you will gain the badge. The course Introduction section on Badge information explains how you can access the badge.

You might even feel inspired to come back to aspects of the course at a later stage and explore the links for further research in more depth.

Course survey

We are always keen to hear about our students’ experiences when studying with us so that we can further improve our teaching provision. Therefore, we would be grateful if you could take the time to complete a short course survey to give us your feedback on studying this course.

End-of-course quiz

The End-of-course quiz covers topics from part 1 and part 2 of the course.

It is a great way to check your understanding of what you have learned on this course.

Here is a link to Part 1 of the course, if you would like to review the topics covered.

The quiz contains 14 random questions and each question allows you multiple tries to get the correct answer.

You are allowed an unlimited number of attempts to pass the quiz. Each attempt at the quiz will give you a new set of 14 random questions.

To obtain your digital badge you must achieve a minimum score of 60% to pass the quiz.

Attempt the End-of-course quiz now.

Further Research

To learn more about the history of the Scots language, explore these two documents produced by the Scots Language Centre with timelines that help you understand how Scots evolved, how it was Anglicised and how it was accepted as a language in its own right again in the 21st century:

To find out more about the use of Scots in online contexts today, read this article by two young academics from Glasgow University: Jamieson, E. and Ryan, S. (2019), How Twitter is helping the Scots language thrive in the 21st century, published in The Conversation.

You might want to follow Michael Dempster, the author of this unit, on Twitter (@DrMDempster), where he posts as Cyberscot . Michael Dempster is currently the Scots Scriever at the National Library of Scotland and posts on Twitter in this role @ScotsScriever .

Irene Watt published an article in The Conversation about how the series Outlander is helping Scots thrive today: Outlander is boosting a renaissance of the Scots language – here’s how.

If you want to find out more about the 2011 census results in relation to the use of Scots language, explore the Scots Language Centre website which features an analysis and commentary of the census data.

You may also want to look ahead at the plans for the 2021 census and explore the relevant sections of the Scotland Census website.

Robert Millar published an instructive paper on the democracy of language use in Scotland, with a specific focus on Scots, which he labels as a ‘dislocated language’. He explores the elements that are necessary for the revitalisation of the Scots language in Scotland. Yet, Millar here also claims that these elements are misunderstood by both practitioners and end-users of the Scots language – one of these elements is the standardisation of Scots.

In this unit, you learned that elocution that was supposed to help speakers of English in Scotland to ‘eradicate’ their Scottish accents. Here is an example of a chapbook printed for young readers, which was designed to help them learn to speak ‘properly’. It is The Elocutionist, a selection of popular poems for recitation in the archives of the National Library of Scotland.

Watch the BBC video Inside the Scottish Twitter Exhibition to learn how this exhibition ‘worked’.

Find out about the background story to Robert Burns’ song ‘The Deil's Awa Wi the Exciseman’ on the Scots Language Centre website.

Discover more about Burns’ own career as an excise man on this website.

To explore in more depth the discussions around advantages and disadvantages of standardising the Scots language, read: Costa, J. (2017) ‘On the Pros and Cons of Standardizing Scots’ in Pia Lane, James Costa, Haley De Korne (eds) Standardizing Minority Languages .

To find out more about the language policy in Northern Ireland regarding the three indigenous languages, Irish, Ulster Scots and English, read: Núñez, G. G. (2013), Translating for linguistic minorities in Northern Ireland: A look at translation policy in the judiciary, healthcare and local government, in Language Planning.

References

Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Classroom: Image by Wokandapix from Pixabay

Hands image: Image by Myriam Zilles from Pixabay

Quines: Poems in tribute to women of Scotland, by Luath Press, is used with the kind courtesy of Gerda Stevenson

Anti Littering sign: © Copyright Walter Baxter https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/808270. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Chalkboard: Siyah Kedi Photography - https://www.flickr.com/photos/83073875@N00/34902600916 This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

Sewing Machine: ezthaiphoto/123RF

Sign Post: © Nick Scott plaques/sign photos/Alamy.

Auld Scotts Words Diane Andersonct

David Hume: National Galleries of Scotland. Photography by Antonia Reeve.

Extract A brief history of Scots and its Anglicisation: Scots Language Centre

Extract ‘Scottish Twitter…’: Taken from https://www.edinburghlive.co.uk/news/edinburgh-news/scottish-twitter-visitor-centre-coming-16749606

Extract ‘wis walkin home…’: @marcsimps0n. Tweeted 28 September 2017. Quoted here: https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/whats-on/edinburgh-festival/scottish-twitter-reveals-winner-funniest-tweet-launch-fringe-visitor-centre-542380

Extract ‘Keepin’ da Shetlan’ dialect alive…’: Wir Midder Tongue. Found on Facebook 2018, https://www.facebook.com/groups/WirMidderTongue/

Screenshot: twitter.com/drmdempster?lang=en. Courtesy of Michael Dempster