Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Sunday, 5 May 2024, 5:54 PM

3. Understanding infidelity

3. Understanding infidelity

Infidelity may be considered as opposite to monogamy (having a sexual and emotional relationship with only one partner) and both are only one aspect of how humans conduct sexual and emotional relationships. For this reason, in order to understand infidelity, it makes sense to consider broader theory on human mating behaviour including theory on monogamy.

Researchers who have tried to explain mating behaviour in humans have considered what can be learned from three overlapping sources of data:

- the mating behaviour of other animals, in particular apes

- evidence and hypotheses about the impact of the evolutionary history of human beings

- evidence of historical and contemporary cultural variation in human attitudes and behaviour around mating.

These strands of theory and research are further discussed in the next sections. Continue to Section 3.1 The evolution of monogamy.

3.1 The evolution of monogamy

So far you have considered your own understandings and definitions of infidelity and where these might come from. Now it is worth thinking about your attitudes towards monogamy.

Activity 3.1 View of monogamy

Discussion

In some regards Britain may be an increasingly sexually tolerant society – for example large scale research in the UK suggests growing acceptance of same-sex sexual relationships (Mercer et al., 2013) – and yet attitudes towards infidelity appear to have hardened. In the British National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles survey, between 1990 and 2012 there was a big rise in the number of men and women who responded that ‘non-exclusivity in marriage’ was ‘always wrong’, up from 45% to 63% for men and from 53% to 70% for women – a combined increase in disapproval ratings of over 17% in just 12 years (Mercer et al., 2013).

Hypotheses about monogamy/infidelity which consider animal mating behaviour, as well as those focussed purely on human evolutionary history, share a core assumption that monogamy in humans has evolved because it has conveyed advantages in reproduction and survival, which have led to the successive inheritance of genes that push humans towards monogamy. As de Waal and Gavrilets (2013, p. 15167) write:

Biologists prefer to place monogamy in a broad comparative perspective to determine what factors may have promoted its evolution. Why is monogamy ten-times more common in birds than mammals? Additionally, even though relatively common in primates, why are there no primates—other than humans—in which multiple reproductive pairs live together?

For researchers who take this approach, a long-standing argument is that monogamy may have evolved in humans because without male investment in infant and childcare (including contribution of his food resources) human children are less likely to survive. However, others have argued that monogamy evolved either as a strategy to prevent infanticide by competing males or as a form of mate guarding necessary due to (dispersed) geographic distribution of females (de Waal and Gavrilets, 2013).

One reason why researchers have focussed on trying to explain male human monogamy is that they are puzzled by it. This is because (assuming the infants survive to themselves reproduce) the most effective way for a man to ensure his genetic legacy is to father as many children as possible, and the best way to do that is to have multiple female partners – i.e. to engage in sanctioned or unsanctioned (e.g. cheating) polygamy. In contrast to men, women do not need to worry about whether their child is in fact genetically ‘theirs’ thus – in the evolutionary argument – their primary evolutionary motive is to ensure child survival, which is presupposed to lead to a concern with access to resources (and attraction to more resource-rich males).

Yet even for women there may be evolutionary payoffs to being unfaithful in terms of ensuring greater genetic variance in children, which may increase infant survival and hence their reproductive success (Zietsch et al., 2015). Zietsch et al. are one of a number of researchers who have argued that a propensity for infidelity has discernible genetic markers. The work of these authors, and those like them, underlines that researchers have used animal/biological/evolutionary arguments to suggest that both monogamy and a propensity for straying outside a couple bond are heritable, ‘natural’ human traits.

3.2 Social context and monogamy

In contrast to those who seek to uncover the biological/genetic foundations of human monogamy/infidelity, there are researchers and theoreticians whose interest is in the variable (temporal and geographical) ways that monogamy and infidelity manifest as a result of their social context. An example of this type of research comes from studies which have sought to improve the effectiveness of AIDS prevention campaigns by getting a better understanding of the socio-cultural contexts for extramarital sex of various communities (e.g. Smith, 2007; Tawfik and Watkins, 2007).

Findings include that in rural Papua New Guinea, sexual monogamy may not be seen as necessary for a happy marriage (Wardlow, 2007); that in the slums of Nairobi the range of types of marital status, including polygamous, influences women’s rates of sexual monogamy (Hattori and Dodoo, 2007); that in rural Mexico, men define ‘safe sex’ in terms of reputational not HIV risk, with the result that sex with other men is perceived as lower risk than sex with women (Hirsch et al., 2007). The point of these disparate examples is to underline how social-cultural geography influences how sexual infidelity is understood, defined and enacted.

Another way to study monogamy is to study (typically ‘Western’, often English-speaking) subgroups who practise non-monogamy. In practice this has often meant a focus on people who self-define as ‘swingers’ or ‘polyamorous’; the distinction is that typically swingers engage in ‘sexual’ non-monogamy while polyamorous people look for relationships which are consensually both sexually and emotionally non-monogamous.

Researchers have also focussed on sexual minority populations, particularly gay men, with the understanding that outside heterosexual norms people can, and do, have the opportunity to conduct relationships differently – including practising consensual non-monogamy. Moors et al. (2014) provide an example of this type of research with their paper titled: ‘It’s not just a gay male thing: Sexual minority women and men are equally attracted to consensual non-monogamy’.

In Activity 3.1 we looked at British research which suggests a hardening of attitudes against infidelity. However, there is other evidence that consensual non-monogamy may be becoming more common. A US study based on close to 9000 young single adults, found that more than one in five had engaged in consensual non-monogamy at some point in their life. While men and non-heterosexual people were more likely to report engagement in consensual non-monogamy, lots of other variables including age, ethnicity, income, education level, and religious and political affiliation, were not associated with having engaged in consensual non-monogamy (Haupert et al., 2016).

To check your understand of the various theories for monogamy and infidelity reviewed in Sections 3.1 and 3.2 try the following matching activity.

Activity 3.2 Checking understanding of theories of monogamy and infidelity

Place the statements in the correct place on the grid and then click ‘check your answer’. If any are incorrect you can either click ‘try again’ or ‘reveal answer’ to see the correct combination.

3.3 Applying understandings of monogamy and infidelity

You have just read a brief overview of the various empirical traditions of research around monogamy versus infidelity in humans. As you will have noticed from this incomplete summary, there is a lack of a clear agreement by researchers about whether human infidelity is an evolved predisposition, genetically influenced, potentially adaptive and ‘natural’, versus whether it is something that is culturally and temporally fluid, socially constructed (as discussed in Activity 2.6).

This area is therefore a good example of one in which different researchers draw quite different conclusions, based on the different evidence they use, their starting position in terms of ontology and epistemology, as well as broadly, their approach to ‘doing science’, and their research aims (think here about the specific aims of the research examining infidelity in order to improve AIDS reduction public health initiatives). It is also possible (though this is more accepted by qualitative than quantitative researchers usually) that the different approaches taken by researchers also reflects their personal and cultural positioning, and even their values and beliefs on the topic.

In the next activity you are going to consider what these theories might mean for how you think about infidelity in Rhianna and Oliver’s relationship.

Activity 3.3 I-Spy episodes 2 and 3

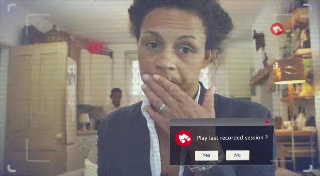

Watch the next two films in the series. In the videos you can see Rhianna’s reaction to finding out that Oliver has been chatting with Minnie and what she does next.

Transcript: I-Spy episode 2

Transcript: I-Spy episode 3

In the text box below, write down what theory of monogamy you think Rhianna might endorse (e.g. as natural/evolved versus socially constructed). What might be the implication of Rhianna’s view of monogamy for working with her therapeutically if she walked into your counselling room the day after the events in episode 3 occurred?

Discussion

Rhianna does not seem to question that what Oliver is doing is a violation of the couple agreement; as such it could be argued that she is accepting the idea that monogamy is not only morally right but also natural for couples. She also talks about how a friend almost lost her house after her marriage broke up, so she is showing concern around the potential impact on her (and her and Oliver’s son) financially/in terms of resources if the relationship with Oliver ends. According to researchers who argue for an evolutionary origin to monogamy, this worry over resources is what women are most concerned with (but you might not agree!).

All of this might imply that Rhianna would see monogamy as something that has evolved because it is better for couples/humans. If this is her view it could potentially be harder for her to explore more complex understandings of both her own and Oliver’s behaviour, as a counsellor/psychotherapist might wish her to do in therapy.

3.4 Implicit theories of infidelity in counselling practice

Up to this point you have been considering theories of infidelity and monogamy that have been developed in academic areas outside of counselling and psychotherapy practice. In the next sections you will consider research on implicit theories on infidelity developed from within counselling and psychotherapy.

Implicit theories are private ‘mindsets’ or beliefs that have been studied primarily in social-psychological and educational contexts (Schroeder et al., 2015), but also in the way therapists’ implicit beliefs (alongside their explicit theoretical orientation) impact on therapy process and outcome (Najavits, 1997). In our own research in this area (Vossler and Moller, 2014), we were interested in couple counsellors’ own implicit theories on infidelity. Consider these aspects by engaging in Activity 3.4.

Activity 3.4 Therapists’ implicit theories on affairs

1. Consider the following statements about the reasons for infidelity and pair them with the correct type of implicit theory.

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

Deficit model – Affair is a symptom not the primary cause of marital distress/deficits.

Contextual factors – Affair is related to contextual factors ‘outside’ the primary relationship.

Systemic model – Affair is linked to the relationship interaction and dynamics between partners.

a.Counsellors explain infidelity not so much as a product of individual motivations/decisions but as resulting from the interplay of individual factors and relationship processes in which both partners are involved.

b.Counsellors identify various issues in the environment of the relationship that may have contributed to the affair, including e.g. stress at the workplace, difficult experiences in the families of origin.

c.Counsellors see infidelity as a response to unmet needs in the relationship. The unmet needs can be emotional needs (e.g. lack of attention or affection) or of sexual nature (e.g. couple no longer have sex anymore with each other).

- 1 = c

- 2 = b

- 3 = a

Discussion

These different implicit theories are not mutually exclusive. For example, relationship conflicts and communication problems can be explanatory factors in both a deficit and systemic model. However, what many counsellors seem to assume is that the underlying psychological motives for infidelity are often linked to perceived problems or deficits at the individual and relationship level.

Pause for reflection

Which implicit theory or model do you tend to hold? In which ways do you think these different implicit theories influence the way counsellors work with infidelity?

3.5 Functions and types of affairs

In practice, affairs may serve many reasons and can have different functions, dependent on relationship history and context. Infidelity might not always be ‘caused’ by a problem (‘deficit’) – either in the relationship, or on the individual level (e.g. sex addiction, attachment issues).

As the renowned couple psychotherapist Esther Perel illustrates in her book The state of affairs: Rethinking infidelity (2017), in practice we might meet seemingly healthy relationship partners, who have happy relationships yet still have affairs. To discover some of the ‘non-pathological’ types of affairs identified by Perel, based on her clinical work, try Activity 3.5.

Activity 3.5 Types of affairs

For scenarios 1, 2 and 3, select which type of affair they are from the definitions below:

Existential affairs: Affairs that open up possibilities and experiences of e.g. validation, power, confidence, freedom. Infidelity can also be seen as an act of ‘self-reclamation’ for partners suffering from a ‘de-eroticised’ self (e.g. due to focus on mother/career role, domestic familiarity) (p. 185).

Protective affairs: Infidelity as chance to escape, and maybe exit, an abusive primary relationship (‘The victim of the affair is not always the victim of the marriage’, p. 216). Infidelity as a rebellion of the rejected (e.g. lack of sex in the primary relationship, ‘enforced celibacy’).

Stabilising affairs: Infidelity with the function to preserve the primary relationship as it helps to keep it in balance, e.g. by taking the pressure off it, or meeting needs that can’t be met in the primary relationship. However, this might sometimes imply that at least segments of the primary relationship might not be ‘healthy’ (e.g. sex life).

a.

Existential affair

b.

Protective affair

c.

Stabilising affair

The correct answer is b.

a.

Existential affair

b.

Protective affair

c.

Stabilising affair

The correct answer is a.

a.

Existential affair

b.

Protective affair

c.

Stabilising affair

The correct answer is c.

Perel argues that in addition to these three types of affairs, sometimes relationship partners might also seek affairs in the context of identity crisis or re-arrangements of their self-concept/personality. This can, for example, include searches for a new self/selves (infidelity provides ‘an alternate reality in which we can re-imagine and re-invent ourselves’, p. 155), or the return to ‘unlived life’ options (e.g. reconnecting with former exes via social media).

Pause for reflection

The understandings of infidelity that Perel proposes are quite different to the other theories of infidelity discussed to date. What is your response to them – including the idea that there can be positive reasons to have affairs?

3.6 Predicting infidelity

To date we have been examining both the theories and research that seek to explain why human beings might engage in infidelity – non-sanctioned extra-dyadic sexual and/or emotional relationships versus engaging in consensual non-monogamy or monogamy. Much of the research we have considered is concerned with the function or individual benefits that accrue from different types of mating behaviour – i.e. theoretically why someone might cheat. A different kind of question is to ask empirically what factors might predict infidelity. There is a long-standing body of research which has used survey data to try to do exactly this. Such research is useful in counselling practice as it can help counsellors understand what might be ‘vulnerability factors’ for those in a couple relationship.

The table below is taken from Fincham and May (2017) and provides the authors’ summary of knowledge about infidelity predictors.

| Demographics | |

| Gender | Males > females; however gender gap is closing |

| Minority status | African American > Whites |

| Education, age, income | All have been related to infidelity but no consistent pattern of findings |

| Individual | |

| Personality | Neuroticism, narcissism |

| Prior infidelity experience | Infidelity in family of origin; Previously engaged in infidelity |

| Number of sex partners | Greater number of sex partners before marriage predicts infidelity |

| Alcohol | Problematic drinking, alcohol dependence, illicit drug use |

| Attachment | Insecure attachment > secure attachment |

| Psychological distress | Greater psychological distress associated with infidelity |

| Attitudes | Permissive attitude toward sex; Decoupling of sex and love, closeness; Willingness to have casual sex |

| Relationship | |

| Relationship dissatisfaction | Dissatisfied > satisfied; Some evidence of bidirectional effects |

| Commitment | Lower commitment > higher commitment |

| Cohabitation | Prior nonmarital cohabitation > marital cohabitation only; Premarital cohabitation with spouse > no premarital habitation |

| Assortative mating | Partners of same religion, levels of education less likely to cheat |

| Context | |

| Work | Number of days spent traveling for work related to infidelity; Job requiring personal contact with potential sex partners; Larger fraction of opposite sex co-workers in work place related to infidelity for men; Both spouses employed associated with less cheating; One working spouse with other a stay at home spouse related to increased infidelity |

| Religion | Less infidelity is associated with: Attendance at religious services; Viewing the Bible as the literal word of God; Prayer focused on partner well-being |

| Internet | Given existence of sites that facilitate infidelity, casual sex, it is likely that visiting such sites promotes infidelity |

Activity 3.6 Infidelity vulnerabilities

After you have looked at the table, try and answer the following questions:

3.7 Characteristics of online affairs

The distinction between ‘offline’ and ‘online’ affairs is becoming increasingly blurry, which means that lots of the theory and research (e.g. about predictive factors) about ‘traditional’ infidelity is also relevant to online affairs. However, Hertlein and Stevenson (2010) suggest that there are seven factors that that may – in theory at least (because currently there is little research on this topic) – make online affairs different and perhaps potentially easier to engage in. You’ll learn more about these in Activity 3.7.

Activity 3.7 The 7As of online infidelity

In this activity, choose the correct online affair vulnerability factor for each description.

a.

Anonymity

b.

Acceptability

c.

Ambiguity

d.

Accessibility

e.

Approximation

f.

Accommodation

g.

Affordability

The correct answer is d.

a.

Affordability

b.

Anonymity

c.

Acceptability

d.

Ambiguity

e.

Approximation

f.

Accommodation

g.

Accessibility

The correct answer is a.

a.

Ambiguity

b.

Acceptability

c.

Anonymity

d.

Approximation

e.

Accommodation

f.

Accessibility

g.

Affordability

The correct answer is c.

a.

Ambiguity

b.

Approximation

c.

Accommodation

d.

Accessibility

e.

Affordability

f.

Anonymity

g.

Acceptability

The correct answer is g.

a.

Approximation

b.

Ambiguity

c.

Accommodation

d.

Accessibility

e.

Affordability

f.

Anonymity

g.

Acceptability

The correct answer is b.

a.

Accommodation

b.

Accessibility

c.

Affordability

d.

Anonymity

e.

Acceptability

f.

Approximation

g.

Ambiguity

The correct answer is f.

a.

Accommodation

b.

Accessibility

c.

Affordability

d.

Anonymity

e.

Acceptability

f.

Ambiguity

g.

Approximation

The correct answer is a.

It is worth noting however, that there is not enough research (yet) to really know what might predict an online affair or if the predictors are in any way different to those for face-to-face affairs. This said, there is increasing evidence for something referred to as the Online Disinhibition Effect (Suler, 2004).

The Online Disinhibition Effect is related to the ‘acceptability’ factor in the table above and refers to the finding that people are less inhibited online (e.g. Fletcher-Tomenius and Vossler, 2009). ‘Less inhibited’ in this context means behaviourally – people may be doing things online that they would not in other spaces – and emotionally, in that they are quicker to reveal personal things about themselves. Online disinhibition increases the likelihood that internet relationships involve strong emotional connections and may build a sense of intimacy, trust and acceptance more quickly than in face-to-face settings. The combination of quickly developing emotional intimacy and behavioural disinhibition makes it easier to understand why someone might, for example, engage in cybersex.

3.8 Online affairs in counselling

From our own work in this area (Vossler and Moller, 2020a) we would suggest that there are some aspects of online affairs that are potentially particularly relevant for counselling because they may increase the distress of someone who discovers a partner’s affair. Consider these aspects by engaging in the activity below.

Activity 3.8 Aspects that create distress in online affairs

1. Consider the following statements about aspects of online infidelity. Pair the correct consequence with the correct statement.

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

Feels like a particular betrayal for partner on receiving end of affair; means that the couple’s home no longer feels safe.

This means people can feel they have a ‘license’ to engage in internet infidelity without perceiving it as such (Mileham, 2007).

Permanence and detail of the infidelity record online can interfere with the need to rebuild trust/move on.

The potentially addictive nature of digital spaces has led to suggestions or perceptions (Vossler and Moller, 2020a) that online spaces may actually encourage infidelity.

a.Real or virtual? − Because interactions with an affair partner are happening online it can be more difficult to know what is ‘real’ or not.

b.Addictive quality − There has been quite a lot written on the addictive nature of digital spaces, with research on internet addiction, online gaming addiction and mobile phone addiction. All this suggests that online interactions may be harder to resist.

c.Permanence of the record − Infidelity is often discovered through discovery of email/text/social media communication between affair partners. This permanent record may be long and full of emotional and sexual details about the affair.

d.Occurs at home − Online infidelity often happens in the space where a couple live (rather than conventional affairs where the interactions typically take place outside the family home).

- 1 = d

- 2 = a

- 3 = c

- 4 = b

a.

Occurs at home

b.

Real or virtual?

c.

Permanence of the record

d.

Addictive quality

The correct answers are a and c.

a.

Permanence of the record

b.

Addictive quality

c.

Real or virtual?

d.

Occurs at home

The correct answers are b and c.

Having considered how infidelity is defined and understood it is timely to consider the implications of this for how infidelity can most effectively be worked with in counselling and psychotherapy.

Next continue to Topic 4 Working therapeutically with infidelity.