Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 9 March 2026, 6:39 AM

Module 1: Personal development – how self-esteem impacts on learning

Section 1: Ways to explore who pupils are

Key Focus Question: How can you help pupils explore who they are in ways that are sensitive and stimulating?

Keywords: class management; questioning; group work; thinking; data gathering; respect; sensitivity

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- developed your skills in organising the class in ways that will help pupils show respect for each other;

- developed your skills in asking questions to encourage thinking;

- used different ways to gather data to help pupils discuss who they are.

Introduction

We all learn best when we feel comfortable and safe. As a teacher, one of your key roles is to develop a supportive classroom environment where everyone is able to participate fully and feels they are respected and their ideas are listened to.

This section explores how to do this by looking at different ways of organising the class. You will help pupils learn how to treat each other with respect by:

- helping them understand their similarities and differences;

- asking them to share opinions and feelings;

- giving them tasks where they can ask each other questions and listen to the answers.

1. Organising pupils in groups and pairs

Young children often find it easier to identify difference rather than similarity. In this part, we show two ways to organise your pupils that will help them to explore differences and similarities.

They will:

- learn how to share information and contribute to discussions;

- learn about themselves and each other;

- have better self-esteem as they realise their ideas are as valued as much as those of others.

As a teacher, it is important for you to encourage this – if your pupils all understand their similarities and celebrate their differences, they will treat each other better. You should act as a role model, treating your pupils fairly and equally.

Before starting, it is a good idea to reflect on this and think about whether you treat your pupils respectfully. Do you ever have a ‘bad day’ when you shout at them for no good reason? Do you have favourites who you treat more kindly than others? If you can answer these questions honestly, you can take steps to make sure that all your pupils are treated fairly and respectfully.

To work in this way, you need to ask yourself questions to help you plan these activities, including: What questions will the pupils ask each other? What information will they need to find out? Will they work in groups? In pairs? How will you organise this? How will you give them instructions to do the activities? See what the teacher does in Case Study 1 before trying Activity 1 with your class.

Case Study 1: Working in groups to explore similarities

Chanda teaches at a rural primary school in Mwenda, Zambia. He is working with his pupils to develop a positive classroom environment. He is looking at the pupils’ similarities and differences and asks them to think about the ways in which they are all the same.

First, the whole class practises making sentences, e.g.: ‘We all like food’; ‘We all go to school’. Next, he puts them in groups of five to think of five sentences beginning: ‘We all …’ with one pupil in each group writing the sentences on a piece of paper.

After ten minutes, each group reads out one sentence. If the class agrees with the sentence, Chanda writes it on the board.

Using the sentences, he shows the class the different ways in which we are the same:

- e.g. physically – ‘We all have skin’;

- e.g. how we experience the same kind of feelings – ‘We all feel happy’;

- e.g. situation – ‘We all are school pupils’.

Chanda is pleased with the ideas from his class and plans to use this as a starting point to look at differences.

Activity 1: ‘Are we the same?’

Read Resource 1: Similarities and differences, before you carry out this activity.

- To introduce the idea of ‘the same’, start by asking easy questions. Hold up two pencils and ask: ‘Are they the same? Why?’

- Hold up a pen and a pencil. Ask: ‘Are they the same? Why?’

- Repeat this, using different objects.

- Ask two children to step forward. Ask: ‘Are they the same?’

- Be careful. If they are girls, the pupils might say ‘Yes!’ If it is a boy and a girl, they might say ‘No!’ But they might give other answers e.g. the children might be the same height or have the same name.

- Split the class into pairs. Ask them to look at each other’s features including such things as height, foot size and possibly hair, eyes etc. and list how they are similar.

- Share their ideas, one group giving one idea at a time.

Did they listen to each other? Did they accept the idea of being the same but different? What evidence do you have for your answer?

2. Finding out what pupils think and feel

Understanding differences in people’s opinions and feelings is important in developing good relationships. This is essential when dealing with a class of young people, from many different contexts, (backgrounds and settings), with different opinions and feelings. Your pupils need to understand this to help them communicate effectively and sensitively with each other.

However, before we can learn to understand different opinions and feelings, we first need to recognise them.

You can compare people’s opinions by organising a survey. You need to plan how to:

- organise the survey;

- explain it to the pupils;

- check that they have understood.

Case Study 2 and Activity 2 show ways of doing this, and Resource 2: Asking questions about feelings offers some ideas to help your planning.

Case Study 2: Using groups to discuss opinions and feelings

One week Mr Obeng used the ‘Do you like...?’ survey with his primary 5 class (see Activity 2). He recorded their answers and stuck them on the wall. He often found pupils reading them and talking together.

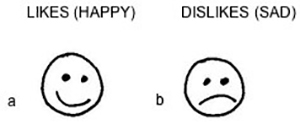

The next week, Mr Obeng asked again about likes and dislikes, but this time, he drew two faces on the board:

For each question, they counted the number of ‘likes’ in the class and wrote the number under face a. They wrote the number of ‘dislikes’ under face b.

To introduce the idea of feelings, he wrote ‘HAPPY’ above face a, and ‘SAD’ above face b. In groups of four or five, the pupils named things that made them feel happy or sad. Working in small groups helped involve the quieter pupils.

He repeated the exercise, this time using:

In their groups, the pupils named things that made them feel angry or frightened. They shared the main ideas together as a class. They looked at whether some things occurred in more than one list and discussed why this might be. Mr Obeng was pleased with how thoughtful they were.

Activity 2: The ‘Do you like…?’ survey

Read Resource 3: How to conduct a class survey, and prepare for this activity.

- Perhaps start by asking your class easy questions about what they like and dislike, e.g. ‘Do you all like hiplife?’ or ‘Do you like homework?’

- In pairs, the pupils think of their own questions about what they like and dislike and record these.

- Draw the chart from Resource 3 on the board. Ask your pupils to copy it and choose three of their own questions. With older classes you could put in more questions.

- Explain that they will all ask five pupils the questions and write down ‘Y’ or ‘N’ for the answer under their names.

- Ask the pairs to compare their answers. Ask some pupils to read out their questions and answers so that the whole class can hear the different responses. Discuss what they have found out from the survey.

Think about what the pupils learned from the activity and how you know this.

3. Respecting differences

Appreciating the similarities and differences among your pupils will help you become a more effective teacher. You will be able to plan better to match their needs. If your pupils also understand themselves and others, they will become more confident about participating in class.

As the pupils realise the ways in which they are different from other people, it is important that they should not start to feel isolated or left out. Part of your role is to help them understand that agreeing with people on one thing and disagreeing on others is acceptable and not a reason for conflict.

When a child is seen to be different because of how they look or behave, other children may bully or tease them. Bullying can make children very unhappy. It damages their schoolwork and stops them from making friends.

Children need to learn how to interact with each other. Your role as teacher is crucial for helping them understand the difference between right and wrong.

How can you encourage this? Read Resource 4: Observing your pupils for an initial suggestion. Below are some other ideas you can use. Try them out. Are they successful? Did you have any problems?

Case Study 3: Helping pupils to respect each other’s differences

Mrs Ojo has a boy in her class who is an albino. One day, she had seen some girls laughing at him and calling him names. This made her upset, but she allowed herself to calm down and after school, she asked them: ‘Why were you behaving like that?’ She asked how they would feel if somebody teased them, and how they thought it made him feel. With questions like this, she helped them think about their behaviour. Thinking about this afterwards, she decided to help all her pupils respect each other’s differences.

The next day, in class, she used a story about a child with polio to start a discussion about how her pupils would feel if they had polio. She also used the words and ideas for talking about likes, dislikes and feelings when she needed to talk to the pupils about their behaviour.

When two boys were fighting, Mrs Ojo talked with them, one at a time, to find out why they were angry with each other and helped them resolve their conflict. When one child was sitting alone, she asked others to find out why and make friends with him. This way, her pupils began to look after each other. Mrs Ojo was pleased.

Key Activity: Role play about differences

Read the Key Resource: Using role play/dialogue/drama in the classroom.

- Organise your pupils into groups of five.

- Ask each group to imagine two brothers or sisters whose likes and dislikes are opposite. Ask them to imagine a conflict between them.

- Ask them to role-play the conflict. Two members of the group will be the brothers or sisters. The others could be the mother, father and grandparent.

- First, they should role-play the conflict, and then discuss the conflict all together. Next they should role-play the resolution, which should be a peaceful one.

- Next, the group should discuss their ideas about the causes of the conflict and the resolution.

- Finally, ask each group to act out their role plays to the class, and explain the lesson that they learned. Collect each of these lessons together and display them on the wall to remind everyone.

- If you have time, at the end of each role play, allow the rest of the class to ask questions to the group or give further ideas as to how the conflict could be resolved. Ask questions to the group or give further ideas as to how the conflict could be resolved.

Resource 1: Similarities and differences

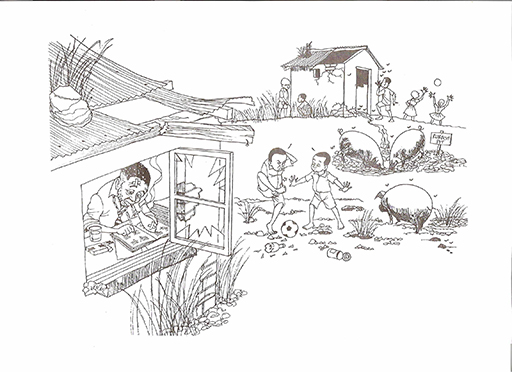

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

There are many ways in which people are the same, from physical features to personality. There are also many ways in which we are different. However, for young pupils, it is often more important for them to feel the same as others and be part of the group.

By understanding ways in which we are all the same, we make the first steps towards understanding ourselves. We also begin to see ways in which we are part of a group or a community. Helping pupils understand that they and their classmates are all equal and should treat each other fairly is an important part of a teacher’s role.

Similarities and differences in appearance

The most obvious way in which people are different is in their appearance. Some are tall, some are short. Some are fat, some are thin. If you are working with your pupils to explain similarities and differences between people, then looking at physical features is an easy place to start. For example, what are the physical similarities and differences between Michael Essien and Kofi Annan?

|  |

You must also be careful: like adults, children can be sensitive about their appearance, so you should try not to draw attention to something that a pupil might be embarrassed about. Instead, focus on similarities such as ‘We all wear clothes’. You will need to be especially careful if you have children with physical disabilities in your class.

In addition, children sometimes tease or bully other children, and drawing attention to differences in appearance might encourage them to behave like this outside of the class. So, as well as helping pupils identify their differences in appearance, you should also emphasise how many similarities there are. If pupils can see the connections between themselves and others, they are more likely to treat others with respect.

Similarities and differences in personality

While it is easier to see the similarities and differences between people’s appearances – the way we look – it is probably more important for pupils to understand the similarities and differences between people’s personalities – the ways we think, feel and behave.

Our opinions and feelings influence the way we behave with other people. They can be summarised as follows:

- ‘Opinions’ cover what people think about things – whether they like or dislike something, or whether they agree or disagree with something. Differences in opinion can sometimes cause arguments and fights, whether with children or adults. Opinions can be based on clear factual knowledge or hearsay which is not always accurate.

- ‘Feelings’ cover people’s emotions – whether something makes them feel happy, sad, angry or frightened etc. Feelings can sometimes be hard to explain, and if someone has different feelings about something to you, it can be difficult for you to understand it.

As children grow up, it is important for them to be able to understand their feelings and emotions, interact with other people, and recognise the needs of others. It is important for children to learn that not everybody thinks and feels the same way that they do. Each person’s ideas, feelings and opinions will have been influenced by their home environment, experiences and carers. This diversity (variety) should not be seen as a problem – except where it goes against legally accepted behaviour. The activities in this module will help pupils begin to appreciate such diversity as a basis for friendship and working together.

As a teacher, you need to understand the feelings of your pupils and make sure that you consider their feelings and differences as you plan their learning. You must be considerate of the fact that some children will enjoy certain activities – e.g. talking in front of the class – and others will not.

However, you must also be fair and equal with your pupils. If you treat each of your pupils differently in class, the children will see this and begin doing the same, both inside and outside of school.

Which feelings are expressed in the photos below? How do you know?

|  |  |

Resource 2: Asking questions about feelings

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

You need to be sensitive when asking questions about feelings. Children might not always want to talk about their feelings in public. You need to ask the kinds of questions that allow children to give answers they feel comfortable with.

One way to do this is to ask questions to the whole class instead of to individuals. Ask questions such as: ‘Who likes …’ and ‘Who doesn’t like …’ with pupils putting up their hands. If they see that they are part of a group, the children will feel less embarrassed about revealing their feelings.

You can do the same by brainstorming different questions (see Key Resource: Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas). For example, ask: ‘What makes you scared?’ and then write all the pupils’ ideas down on the board very quickly. This way, you won’t make the individuals feel too exposed.

If you want them to talk more intimately about their feelings, organise them into pairs or groups to do similar exercises. They will probably find it easier to speak in a small group.

You can also use stories to explore sensitive ideas – this helps pupils to talk more freely as they do not feel they are talking about their own experiences.

You can make up your own stories to share with your pupils. Or you could use the story of Ghanaian street children below to stimulate discussion. Either copy the sheet – one for each group – or read from your copy to the whole class.

After they have heard the story taken from Street Children News, ask them how they feel about the children’s lives. Are they similar or different to their own lives? How would they feel about living like that? What would they like and dislike about this kind of life?

Street Children News: Ghanaian street children

‘Street’ children have been given this anonymous label because the ‘street’ is where they live their lives out: hustling, sleeping, working, eating. The street is their home and this is where their daily struggle is endured.

Currently in Africa there are a few national governments addressing the very real needs of these marginalised citizens; but there simply is not enough money to go around. It is up to grass-roots organisations and NGOs (non-governmental organisations) to reach out to these children and offer them a helping hand.

It gets cold at night in the winter and so street children sniff glue as a guard against the cold and to escape from their struggle to survive for a few short hours.

Quotes from the street

In 2003, Wendy Jones asked street children in Accra some simple questions and recorded what they said. Their lives may seem very different from our lives but by reading their replies we can see that they are people just like us, often with the same dreams and aspirations.

‘If you could go anywhere in the world, where would you go?’

Peter, 19: ‘My home town.’

‘If you had three wishes, what would you wish for?’

Simon, 14: ‘Shoes. One Shirt. Sneakers.’

‘What makes you happy?’

Sandra, 4: ‘Clapping games.’

‘What makes you cry?’

Sandra, 4: ‘When I am hungry.’

‘If you had three wishes, what would you wish for?’

Sandra, 4: ‘A dress. Sandals. Eggs.’

‘What do you think about last thing at night before you go to sleep?’

Godfrey, 18: ‘I think about the next day. Because I think that evening has passed so I have to think about the next day. As for the night I have no place to go and I just sleep.’

‘What would you have if you could have anything?’

Peter, 10: ‘A necklace, a watch, a bed I can sleep in, a TV, a video tape – any tape, a chair.’

‘Tell me about your mother.’

Larni, 18: ‘She wants me to be somebody. Yet I am on the streets.’

‘What would you like to do in your future?’

Larni, 18: ‘In the future, if I'm rich – I know I will be rich – yes, I hope, I hope I will be rich, I will care for street children. Children with broken legs who can't work...’

‘What do you regret?’

Betty, 18: ‘I will say I regret being a street girl and I regret picking a boyfriend. And I regret having bad friends – those that don't give good advice and wish for your downfall.’

‘What’s your favourite thing?’

Aisha, 19: ‘I have a long black dress. I used to wear it and go anywhere. If I go to an exhibition or to visit some people I can wear it. I love my long dress. It's fitted with sleeves. It's black.’

|  |

Adapted from: Street Children Africa, Website

Resource 3: How to conduct a class survey

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Conducting a survey is a very useful way for your pupils to practise many different skills. These include:

- asking questions;

- recording different types of information;

- comparing answers;

- practising speaking and writing;

- finding out more about each other.

However, you need to think and plan very carefully to organise a survey in your class, and also how you will explain it to your pupils.

1. What is a survey?

A survey is a way of gathering information from many different people on a particular topic. It can explore a range of opinions in a group, and help to find out more about individuals.

To gather the information, a survey usually uses a chart to record the responses. The chart below is one example where the answers could be recorded easily and quickly by using a Y for a yes and and N for a no in each box:

| Name: | ……Faith…… | ………… | …………. | …………. | ……….. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you like yams? | |||||

| 2. Do you like…? | |||||

| 3. Do you like…? |

A survey is an interesting way for pupils to practise finding out information for themselves.

Because a survey has many different stages, it can take a whole lesson to complete – or longer, if pupils have to ask people outside school. Providing time for the data collection to happen is especially important so that everyone is involved and able to see the process in action.

2. Choosing your topic

When deciding to do a survey with your class, you need to think carefully about what the survey will be about – what information will you find out? Clearly, the survey should be linked in some way to the topic in class. For example, if teaching about similarities and differences, a survey about the different foods people like might be an idea. The pupils will be more involved if they suggest ideas themselves.

It is important at this stage to think about the skills that your pupils need to develop and practise. Design a survey that matches your learning objectives.

3. Writing the questions

In any survey, it is good for the pupils to think of and write their own questions – each pupil or group of pupils should come up with their own ideas. But you need to think about how you will organise the pupils to do this. Pair or group work is good if it is the first time that they have done this, as then they can check each other’s work.

To help pupils do a survey you may need to decide (by yourself or with the pupils):

- how they are to work e.g. individually, in pairs, or in groups;

- how many questions they should write (3–5 is usually enough);

- what types of questions they should ask (provide some examples yourself and ask them for some more examples to check that they understand);

- how much time they will have to write the questions – 10–15 minutes should be enough for 3–5 questions.

It is important to do all the above with the whole class together before they start working. As they work, go round and monitor their work to check that they really have understood the task.

The type of question they will write depends on the kind of information that they want to find out. For example, if the idea of the survey is to gather information about the numbers of pupils who think/like/do something, then they might write ‘Yes/No’ questions: e.g. ‘Do you like football?’

However, if the idea of the survey is to gather information about the range of interests in the class, then they might write ‘open-ended’ questions: e.g. ‘What sports do you like?’ They will have to think of ways to record the answers.

4. Asking the questions

Every pupil should practise asking and answering questions on a one-to-one basis. Think carefully about how you would organise this. Here are a few suggestions:

- Pupils do not need to speak to everybody in the class. This would take too much time and also be very repetitive. A sample of five pupils may be enough, and maybe no more than ten pupils – depending on the size of your class.

- If they wrote their questions in pairs or groups, they shouldn’t ask each other the questions. Instead, suggest they ask others in the class or school.

Organising pupils into groups to do the survey can be useful if you have a large class. You also need to ensure that all pupils are involved in writing and asking the questions. (See Key Resource: Using group work in your classroom.)

5. Recording the answers

The pupils need to be clear about the responses they are recording and keep these as short as possible.

For example, if they are asking open-ended questions, they can write down one-word answers: Q: What sports do you like? A: football/running/jumping.

If they are asking Yes/No questions, they can write Y or N as an answer.

If they are gathering information on numbers, they could just keep a tally, with one mark representing one person: e.g.

| Favourite sports: | Football | Running | Jumping | Catch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers: | IIIII | IIIIII | III | IIII |

Again, plan this carefully, and explain it to the pupils before they gather their data. To check they understand, you could ask them to explain it to you, too.

6. Comparing answers

After the pupils have asked questions and recorded the information, it is good for them to talk in pairs or groups about their data and compare answers. This data can be used to discuss people’s likes and dislikes and they could draw graphs of the results to make it easy to see the differences and discuss what they mean.

Displaying their findings or asking them to write about their findings will help you understand their thinking and give them the opportunity to think more deeply about the data.

Resource 4: Observing your pupils

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Observing or watching your pupils at work in the classroom or playing in the playground is a very good way to build up a picture of them as people. It tells you who they mix with and whether any pupils are isolated. Such information can help you plan activities that better match their needs.

Do they talk more in groups? If so, by using group work more, you may help them think more and therefore learn more. You can observe at two levels by looking at:

- the social groups in your class and how they do or do not interact. What kinds of conflicts are there, if any? How can you use this knowledge to plan group work?

- individuals and their social skills, interests etc. (Finding out and acknowledging what pupils are interested in outside and inside school can be a very powerful way of motivating them to learn.)

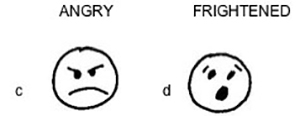

Some aspects you could look out for as you watch your pupils are in the table below. But remember to keep an open mind and readjust your picture as you get to know your pupils better.

Below is an example of how to record pupil observation. A version of this was used in the Literacy Development Across the Curriculum programme in Nigeria.

Tick the appropriate column in terms of the pupil you are observing.

0 = not at all; 1=poor; 2 = fair; 3= good

Not at all (0) | Poor (1) | Fair (2) | Good (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Pupil participates actively in the lesson | ||||

| (b) Pupil produces something creative | ||||

| (c) Pupil works in groups or pairs | ||||

| (d) Pupil shares ideas/information | ||||

| (e) Pupil shows evidence of understanding lesson | ||||

| (f) Pupil is not afraid to ask questions | ||||

| (g) Pupil shows respect for the ideas of members of the class. |

Adapted from: World Bank, Website

Section 2: Planning physical growth and development sessions

Key Focus Question: How can you plan lessons to develop self-esteem?

Keywords: lesson preparation; games; problem solving; whole-school activities; planning; self-esteem

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- planned lessons that are focused on clear learning outcomes to investigate growth and development;

- explored ways to include games and exercises into your lessons;

- used problem solving in whole-school activities.

Introduction

This section focuses on your planning and preparation of lessons. It is important to do this well if your pupils are to achieve what you want them to achieve.

One of your roles is to help your pupils understand the concepts of physical growth and development. These include both the physical changes that will take place as they get older, and also the different things they need to think about and do in order to stay healthy.

As you plan practical activities about physical growth and development, you need to use pupils’ existing knowledge as a base from which to plan and extend their understanding. This section suggests different ways to work in and outside the classroom, which you could also plan to use elsewhere in your teaching.

1. Focus on planning

It is important to prepare yourself for lessons by checking your own subject knowledge. Read Resource 1: Introduction to physical development to refresh your understanding.

You need to think carefully about how you will introduce this topic. Just reading out information and hoping that the pupils understand is not the best way for most pupils to learn. You need to plan your lesson carefully, thinking about what will happen at each stage of the lesson and finding out what they already know and think. See Key Resource: Planning and preparing your lessons for further information.

Each lesson should have a particular learning outcome (intention). In this case, you want the pupils to be able to identify the four basic things that contribute to improved physical development.

For each stage of the lesson, you need to answer three questions:

- How does this activity contribute to the learning outcome?

- What will the pupils be doing to help them learn?

- What will I be doing to support them?

Look at the games and activities you could use. Which ones will support your learning outcomes?

Case Study 1: Considering physical development when organising your classroom

Biduga teaches in a small school in a rural area of Tanzania. This term, her colleague Mary is on maternity leave, so she is teaching a large, multigrade class of 85 pupils from Grades 3–6. This means that she has to deal with a large number of children at different stages of physical development. Biduga knows she needs to consider this when organising her classroom.

She has noticed that the older children often take responsibility for some of the younger children. So, she organises the class into groups, each with a group name and a Grade 6 ‘leader’. The leader checks that each child is present, and gets their group settled and ready for study.

She also finds that the younger children enjoy having many different activities in a lesson. She plans lessons with two strands of activities: one for Grades 5–6 and one for Grades 3–4:

- First, she gives Grades 5–6 some group work or longer exercises.

- Then, she spends time with Grades 3–4, using shorter activities, including simple games.

This means preparing lessons with more stages for Grades 3–4. See Key Resource: Working with large classes.

In this way, Biduga has recognised the differences in her pupils’ physical development and is using it to help plan her teaching.

Activity 1: Planning a lesson on physical development

Resource 1 covers the four principles that contribute to physical development. Write a lesson plan to introduce these four principles to your pupils.

Identify the activities and resources you will use. You could adapt the ‘same or different’ activity from Section 1 of this module but look at similarities and differences in physical growth e.g. height, shoe size, hand and arm length.

Plan your lesson like this:

- Introduction to the lesson and intended learning outcomes.

- Introduce the ideas in Resource 1, using pupils’ previous knowledge.

- In groups or pairs, the pupils do a ‘same and different’ activity or your own activity.

- The pupils do another similar activity so you can check their understanding.

Resource 2: Planning ways to introduce the four principles of physical development gives you more guidance on organising the lesson and gathering resources to support your teaching.

After the lesson, make some notes for yourself about how it went:

- Was it successful? What did your pupils learn?

- Did any part not work so well? If so, why was this?

- What would you do differently next time?

2. Using games in your teaching

In the first part of this section, you considered ways to plan teaching your pupils about physical development. We are now going to look at one element of this: the physical exercise pupils may get while at school or at home.

First, read Resource 3: Using games and physical exercise for ideas.

When planning to use games in your teaching, you need to think about:

- the content of the game, so that it helps the pupils reach the learning objectives you have set for the lesson;

- the organisation of the game:

- How do you play the game?

- How will you give instructions to the pupils?

- How will you check they understand how to play?

- Will they play in pairs, groups or as a class?

- Where will they play – inside or outside?

How long will they play for?

Case Study 2: Using pupils’ favourite games

Mr Nyamekye, a teacher in the township of Ada, wanted to use pupils’ games in his lessons. So he planned a lesson where they would:

- identify their favourite games;

- describe how to play them;

- use the games to learn about different ideas and topics such as sharing and numbers.

To start the lesson, he used the ‘likes and dislikes’ survey to find out what games his pupils knew. To save time, he planned to:

- conduct the survey with the whole class at once;

- record the information on the board himself.

Next, he wanted the pupils to do something themselves. He decided that, in groups, they would write a description of their favourite game, but they would have to include answers to some key questions that he would provide about how to play the game. He included questions such as: Where do you play it? How many people could play? What equipment is needed? What are the rules?

Finally, he built in time for each group to explain their game to the class. They would vote and play one game each week.

Read Resource 4: How Mr Nyamekye taught his lesson for more information on what he did.

Activity 2: A simple number game

Try this game with your class. It practises adding the numbers 1 to 10 and gives your pupils physical exercise.

- The pupils form a circle. You stand in the middle and give them a simple sum, e.g. 2 + 3.

- The pupils jump to form groups whose number answers the sum: e.g. 2 + 3 = 5; they jump into groups of 5.

- A new person stands in the middle, makes up a sum and the game continues.

If your class is large, make more than one circle or play outside to have more room.

If you have a multigrade class, make circles for each grade. Lower grades can practise adding and subtracting. Higher grades can practise multiplication and division.

How did your pupils react to this game?

What did they learn?

How can you adapt this game to a lesson plan for science or English? What changes would you make in organising it but still keep the physical activity?

3. Teaching about healthy living

In the first part of this section, we identified key factors needed for healthy physical development. Now we investigate how your school can promote these ideas with the pupils and local community.

Having discussed using exercise and games in your lessons, you now need to promote the importance of a) good food, b) protection from illnesses, and c) clean surroundings, but this will have to be done sensitively.

This can be done by making the school a health-promoting environment.

This will involve discussion with the school staff, about:

- setting the school up as a good example for pupils and the community. To resource this, you may need to plan to involve the community and other people to work together, such as local health clinics and NGOs;

- encouraging healthy living practices in your school by having health promotion activities as part of the regular routine;

- having inputs from experts such as HIV/AIDS coordinators and health clinics. Who will be involved, and when?

Case Study 3: Holding a Sports Day to promote healthy development

Having used games in his lessons, Mr Nyamekye thought about other ways he could promote healthy development at school.

He decided to hold a school and community Games and Sports Day. Once a term, the whole school could compete at games and sports. This would involve sports like football, netball and running, but also some of the learning games such as one about the points of the compass that he had been using in lessons.

To plan this, he listed the people he should speak to, such as the head teacher, other teachers, the Parents/Teachers’ Association (PTA) and the pupils.

Having gained the support of the head teacher, he planned the competitions with the staff, some interested pupils and the PTA. First, they decided the time – it would start at 09.30 and finish at 12.30. Then they chose the different activities. They organised the games and races according to classes (making sure that any pupils with special needs were included), and wrote a schedule of activities for the session. Then they planned who would help on the day with announcements, results, prizes etc. – the PTA, the School Management Committee (SMC), the teachers and some older children.

They planned it over two to three weeks, which meant that it was well organised and a huge success.

Read Resource 5: Mr Nyamekye’s other ideas for health promotion for more ideas.

Key Activity: Problem solving for a healthier school environment

First, discuss the picture in Resource 6: Picture of an unhealthy school environment with your pupils and ask them to identify the problems in this school environment.

Organise your pupils to carry out a survey of your school environment to see if it is health promoting or health demoting. Send the children around the school in pairs or threes to note down anything in the school environment that fits into these categories.

Next, each pair/group presents their findings to the whole class. You make a list of their findings and put them on two posters on the wall – one for health promoting, one for health demoting. Discuss what needs to be done to make changes for a healthier school environment. Remember to celebrate the positive aspects of your school environment.

Ask your headteacher if you can present your findings to the whole school in assembly. Invite everyone in the school to form teams to tackle all the tasks that need changing to make your school environment fully health promoting.

You may need to ask parents or other community members for help. You will also have to encourage the children to be creative and think of ways to improve the school without spending a lot of money.

Resource 1: Introduction to physical development

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

We are all growing all the time. We are growing physically, but are also extending our ideas and understanding, and often these are happening alongside each other.

During the years that children are at school, they go through many physical changes. You can see this by comparing pupils in different classes. The older children are taller and stronger, and they can usually also express themselves better. As part of the natural process, children also develop sexually once they reach their teenage years.

Children cannot develop and grow on their own. Just like a plant needs water, sun and good health to develop, people need certain things to help them. They include:

- good food;

- exercise;

- protection from illnesses;

- clean surroundings.

Each of these things contributes to the physical development of the child.

- If a child does not eat well, they will not grow as quickly as others. Food contributes to other things, too: the amount of energy that children have, how much they are protected from illness etc.

- If children do not exercise, they will not develop their arm and leg muscles and so will not be as strong. Physical exercise also helps develop their bodily coordination when doing exercises like running, jumping and catching. Coordination helps with other skills, like reading and writing. Physical exercise is also good for well-being and physical growth.

- If children are not protected from illnesses, they will become sick more often, which will affect the way in which they grow. If children are ill, they cannot exercise, and so will not develop their muscles. If they are ill, they also find it hard to study, and so will fall behind in their learning.

- If children do not have clean surroundings, they are more likely to catch diseases. Diseases will affect them in the same way as illnesses.

It is important for you to introduce these simple ideas to your pupils at an early stage so that they can get into healthy habits as part of their everyday lives, but you will need to be sensitive to the context of the community in which you work.

Resource 2: Planning ways to introduce the four principles of physical development

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Look back at Section 1 of this module. Pupils were comparing ways in which they were the same and different. How could you use this classroom activity to introduce the four principles of physical development?

For example, you could ask them to compare their ages and sizes, and the different foods that they eat.

To cover the four principles of physical development in a lesson plan, think about these questions:

- What is the key thing you want them to learn?

- How will you introduce the topic?

- How will you organise the first activity? What will your instructions be? Will the pupils work in groups or pairs?

- How will you demonstrate the four principles?

- What resources could you use to help explain them? For example, could you use pictures? Could you bring in different kinds of food? Where would you get them?

- How will you check the pupils’ understanding?

- What issues do you need to be sensitive to in the context of your work?

Write down your answers to these questions on a piece of paper. Then use these to plan each stage of your lesson. Remember to always be sensitive to the context in which you are working in so as not to embarrass pupils.

Resource 3: Using games and physical exercise

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Physical exercise serves many functions. As we know, it helps children build up their strength and fitness. But it can also help pupils to develop social, creative and leadership skills. It can help pupils make friends and learn new things, and it contributes to their emotional well-being.

Think about the range of different physical games and exercises there are:

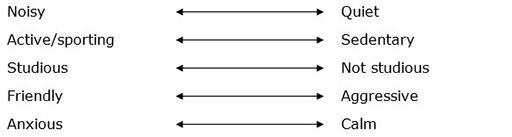

|  Original source: http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk (Accessed 2008) Original source: http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk (Accessed 2008) |

|  Original source: http://www.mindspring.com (Accessed 2008) Original source: http://www.mindspring.com (Accessed 2008) |

|  Original source: http://www.umanitoba.ca (Accessed 2008) Original source: http://www.umanitoba.ca (Accessed 2008) |

Children will automatically invent and play games with each other and you can exploit this as part of your teaching.

The use of physical games and exercises as part of your teaching can encourage pupils to enjoy learning, and so develop a greater interest in coming to school.

By using physical games as part of your teaching, you will also encourage pupils to acquire different talents, skills and behaviour patterns as they participate.

These can include:

- collaborative learning;

- thinking skills;

- sharing resources and taking turns;

- motivation and involvement in learning.

All of these are attributes you should encourage in the classroom, as they will contribute to more effective learning.

Below you will find some examples of Ghanaian games that use physical exercise.

| AMPE |

|---|

Objective: To be the highest scoring team. Equipment: Fast-paced music playing or clapping. Rules: Pupils divide into two teams. One player from one team stands opposite one player from the other team. One of these players is Ohyiwa and the other is Oware. Players begin jumping and clapping with the music. As they land, each manipulates one leg forward, with knee locked. Ohyiwa wins a point if his/her left leg meets the other player’s right leg or if his/her right leg meets the other player’s left leg. Oware wins if his/her left leg meets the other player’s left leg, or if their right legs meet. The team that reaches 10 points first wins. A set of games can be played and the team with the highest number of wins, wins the day. Adapted from: http://www.gameskidsplay.net (Accessed 2008) |

| PILOLO |

|---|

Objective: To find the hidden objects and get back to the finish line as quickly as possible. Equipment: Small balls, sticks, or pinnies. Rules: Select a leader. While the players close their eyes, the leader hides the objects all around the playing area (this may be best played outdoors or in large area with good hiding places). The players gather at a start/finish line. The leader then yells, ‘Pilolo!’ and the players run to find a hidden object and get back to the finish line first. The person who crosses the line first wins. The game is played several times. Adapted from: http://www.estcomp.ro (Accessed 2008) |

Resource 4: How Mr Nyamekye taught his lesson

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Here are the stages Mr Nyamekye used in his lesson:

- He instructed the pupils to talk, in pairs, about their favourite games and list them. This took ten minutes.

- To do the survey, he asked a volunteer pupil to come to the front of the class and ask each pair which game they had chosen.

- He wrote the game on the board and put one tick next to it. If it was a game someone else had already mentioned, he just added a tick. The list on the board started to look like this:

- Football ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

- Skipping ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

- Tag ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

- Catch ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓

- Marbles ✓ ✓ ✓

- The survey took 15 minutes to complete. Next, he asked which game was most popular and which least popular.

- He asked the class to get into seven groups of five. He gave each group one game and asked them to write a description for the class of how to play it.

- He asked them to read their instructions to the class.

There were too many games to describe in one lesson so he decided to do one new game during the last lesson of each day.

To help with this, he gave each group the name of a day of the week. Now each group knew when they should give their description. At the beginning of each day, he asked whose turn it was today.

These lessons used the following format:

- First, the group gave their description of the game and demonstrated it in front of the whole class. This took about ten minutes.

- Then all the other groups practised playing the game as well. If necessary, Mr Nyamekye took them outside. This took 15 minutes.

- Next, he asked them to think about new ways of playing the game, particularly if there were children who found the game difficult to join in with. This helped them to remember what they had learned in class that day.

- Each group came up with different ideas for adapting the game. This discussion usually lasted about 15 minutes.

- Finally, they discussed some of the changes and tried them out together until the end of the lesson.

This way, Mr Nyamekye started using his pupils’ games to help with teaching different subjects. The best ideas he used again. Also, the pupils started playing the new learning games in their free time.

Resource 5: Mr Nyamekye’s class's ideas for health promotion

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

As well as Sports Day, Mr Nyamekye gave his class the opportunity to suggest other ways that the school could support health promotion (see Key Resource: Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas). He already had many of the following ideas in mind but he supported his pupils in coming up with a list first. In fact, they had very similar ideas.

- Pupils and teachers could clean the playground and classrooms after assembly every morning.

- Using rubbish bins would stop people dropping rubbish just anywhere. (It would also stop dogs and rats coming into the school and reduce the possibility of the children and teachers catching diseases or falling ill.)

- Using the school as a local inoculation centre when the health workers were visiting would ensure that children and teachers would all receive regular inoculations. It would also mean that the children would receive some additional health guidance from doctors and nurses.

- Establishing connections between the school and local and visiting health workers would help the school with health resources.

- Developing a school garden would provide food (such as vegetables to make soup) and exercise, as well as learning about the environment.

- A first aid/rest area or room could be created.

- The school could invite visitors to come and talk about particular problems, e.g. HIV/AIDS, malaria.

- They could run after-school exercise or games clubs.

Resource 6: Picture of an unhealthy school environment

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Section 3: Exploring pupils’ ideas about healthy living

Key Focus Question: How can you use prior knowledge and group work to develop understanding of healthy living?

Keywords: group discussion; storytelling; writing; traditional healthy practices; prior knowledge

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used class and group discussion to find out what pupils already know;

- learned how to build on pupils’ prior knowledge;

- used local resource people to motivate pupils to learn.

Introduction

When introducing the study of healthy living into your curriculum, you will need to be sensitive to the setting in which you teach. This section includes investigating your pupils’ prior knowledge – where they get ideas from and what knowledge they bring to the classroom – and using this to develop their thinking about healthy living. By recognising your pupils’ knowledge and how competent they are, you will build up their self-esteem. The activities ask you to use group discussion, practical tasks and local people to explore and deepen your pupils’ knowledge about healthy living.

1. Building on prior knowledge

Your pupils need to know what foods are best for them, but just telling them is not enough. Here, we look at more interactive ways to help them learn and understand.

Importantly, they may already have some ideas about the topic. To find out what these are, you could start your lesson by:

- introducing the topic and asking them ‘What can you tell me about … ’ and noting down their ideas;

- organising them into pairs or small groups to talk about the topic and giving them some open-ended questions to guide their discussion;

- asking them to give their responses, and listing the key ideas you want to take further.

Having found out your pupils’ prior knowledge, your planning – and therefore your teaching – will better match their needs. See Key Resource: Using questioning to promote thinking to help you think of questions to guide their discussions.

Case Study 1: Finding out what pupils know about good nutrition

Mrs Shivute, in TaboraPrimary School in Tanzania, found that her class liked talking about food, so she asked them to list all the foods they liked.

She asked them where the foods came from originally – plants or animals. In groups, they cut pictures of food from old magazines that Mrs Shivute had collected and kept in her classroom and sorted them into different food groups (see Resource 1: Healthy living practices).

They discussed the food types that are good for you and the food types that may taste nice, but are not as good for you.

Mrs Shivute talked of some other foods that they did not mention and asked them to include these in their sorting. She explained about eating a balanced diet if possible and eating more fruit and vegetables and less sugar. The children drew pictures of the different foods.

She asked if they knew why meat and fish are good for them. They had lots of ideas: one boy said meat and fish help children to grow. Mrs Shivute was very pleased and told them about how these foods helped build their muscles.

They talked about the fact that when money is short, they have to eat what their parents can afford and this is not always what they like to eat or what is good for them. They realised that some food was better than no food.

Activity 1: Food group activities

Before you start, you may want to read Resource 1.

- Ask the pupils what they like to eat. They can draw pictures or find pictures in old magazines if you have them.

- Ask the pupils, in small groups, to share their ideas about what types of food are better for them than others.

- Ask each group to share one idea and list these on the board.

- Using their ideas as a starting point, explain the different food groups and how each helps us.

- Ask pupils, in their groups, to match pictures to food groups. Ask them to discuss why the different foods are good for them and what they provide.

- Ask each group to write five questions about different food types. Have a class quiz – each group asks their questions in turn and others answer.

Finally, ask the groups to make food group posters or displays, using their drawings and pictures. You could also use samples or empty food packets. Leave these in the classroom for all to see. (See Resource 2: Ideas for classroom displays.)

2. Organising group discussions

You have introduced your pupils to some ideas about food and nutrition and given them the opportunity to contribute their own ideas during the activities.

However, in talking about healthy living, you also need to encourage them to develop healthy habits, using what they already know. By using discussion you can encourage them to think about their own daily habits and identify ways to improve them.

Possible discussion topics are:

- exercise;

- eating as balanced a diet as possible;

- keeping food safe;

- keeping clean.

Organising a discussion needs careful planning. Where will the groups work? Who will be in which group? You might want groups where there is a good mix of personalities to help discussions and someone to act as leader.

To encourage pupils to participate, set the groups three or four questions. One or two can be easy to answer – e.g. Name three healthy habits – and the others should encourage pupils to explain their ideas – e.g. Which habit do you think is the most important? Why do you say this?

It is important that they respect other ideas and listen carefully to each other.

Case Study 2: Class discussions about healthy living

Mrs Ablor wanted to develop her pupils’ ideas about healthy living. She decided to organise discussions on a different topic, one a week for three weeks.

For each discussion, she introduced the topic using pictures or stories and asked some simple questions to start them thinking. Then she put them into small groups of four or five to discuss a related topic, e.g. Why do we need to keep as clean as possible?

As the pupils were talking, she would go around listening and sometimes joining in and helping to move discussions on.

After five or ten minutes of group discussion, she asked each group to say what they had talked about and explain their ideas.

Finally, with the pupils, she wrote a list of good practices on the board for them to remember and record. The next day, she asked them to look at the list again and suggest which they thought were most important.

Then, Mrs Ablor gave the pupils next week’s topic and asked them to think about their ideas in advance by using one or more of the following methods: talking to each other, talking to their older siblings, asking older people in their family, looking up in books if available, looking out for relevant items in newspapers, on the radio etc.

Activity 2: Planning and organising a discussion

With your own class of pupils, how would you organise a group discussion on healthy living?

- Choose a topic to discuss or make a list for them to choose from. Plan your introduction.

- Think how they will work – in pairs, groups or as a whole class? Design the task – either discussing the answer to a question or ask your pupils to plan an activity to keep healthy.

- Prepare your instructions. How will you check that they understand the task?

- How long will they talk for? 5–10 minutes or more? What will you do while they are talking?

- At the end of the discussion, ask them for their ideas. Think of questions you might ask to help them. How many people will you ask? Plan how you will summarise their best ideas, perhaps by drawing a mind map – or listing ideas (See Key Resource: Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas).

- Discuss with the pupils how they will remember and use these ideas.

Use these questions to plan your lesson on a healthy living topic. After the lesson, ask yourself how well it went and what you would do differently next time to make it more effective.

3. Using local resource people

There are many things for children to know about if they are to remain healthy. Some of these they can learn in school, but many things they can learn at home or in the community.

To encourage them to learn more from the community, you can devise ways to help them find out who they can learn from. This will motivate them to want to learn. One way to encourage this is to give the children homework where they ask their parents or grandparents about something. How would you help the children do this? For example, what information will they gather? What questions will they ask? How will they record the information?

Another way is to invite people from the local community, who know about local healthy practices, into the classroom. This is what one teacher does in Case Study 3. See also Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource.

Case Study 3: Using a local person to learn about local food

Mr Acorlor asks Mrs Fuseini to visit his class to talk about local food. Mrs Fuseini is the first wife of the local chief and every year she visits schools to help the children learn about how food is cooked and stored.

She takes cassava flour, maize meal, dried fish and meat to the school and she tells the pupils about cooking these foods and drying them in the sun.

They identify all the foods that are available locally. The pupils are excited about the visit and listen carefully.

Mrs Fuseini talks about the grain harvest and how long the local store will last and the pupils find out how other local food is grown and stored (see Resource 3: Traditional food storage).

The next day, Mr Acorlor draws pictures of the local foods and the pupils put them in to the food groups. They talk about where the foods come from and discuss in groups how different foods are cooked and preserved.

Mr Acorlor is pleased to see that the pupils have remembered much about the visit. He sees how the new schooling experience motivated them to learn. They planned it over two to three weeks, which meant that it was well organised and a huge success.

Key Activity: Using local resource people

This activity is about planning and carrying out a lesson where you invite a local expert into your class. To plan this effectively, you need to think about the following:

Which local resource people could visit your class? What health topic could they cover? For example:

- a farmer to talk about local food;

- a traditional healer to talk about beneficial plants and herbs;

- a housewife to talk about storing and cooking food;

- a nurse who can explain everyday hygienic practices.

You will need to:

- plan an activity to check the pupils’ prior knowledge of the topic;

- discuss with the pupils what questions they will ask the visitor;

- tell the visitor what to talk about and for how long;

- plan a pupils’ activity after the visit to explore ideas further.

In the last activity, you could assess how much the pupils have learned by asking them to write stories or do role plays to share with the class.

Now carry out your lesson as planned above and think about its effectiveness.

You could develop your pupils’ findings into a class presentation for the school assembly.

Resource 1: Healthy living practices

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

The following information is useful for different topics associated with healthy living. Use this as a resource for designing activities and guiding discussions.

A. Good and bad foods

It is important to eat and, if possible, to eat a balanced diet. In Ghana, there are six food groups and each group helps us in different ways.

Animal foods and animal products. This is the first group. Examples include meat, chicken, fish, snails, eggs, milk, cheese. These foods when eaten provide the body with protein. Proteins help us to grow big and strong.

Beans, nuts and oily seeds. This group includes beans of all kinds – for example cowpea, bambara beans, broad beans, soya beans, groundnuts, cashew nuts, agushie, were-were or neri. This group provides the body with plant protein. Protein from these sources also helps us to grow big and strong.

Cereals and grains. These include corn (maize), guinea corn, sorghum, millet. This food group provides the body with carbohydrates. Carbohydrates give us heat and energy. Carbohydrate foods are termed energy-giving foods.

Fruits and vegetables. Examples are oranges, pineapple, pawpaw, banana, avocado pear, tomatoes, onion, carrots, cabbage, garden eggs, okro, kontomire, aleefu, pepper, bomma. Fruits and vegetables provide the body with vitamins and some minerals. These protect us against diseases and also help with normal growth and development.

Fats and oils. Examples include palm oil, shea butter, palm kernel oil, soya bean oil, frytol. This food group provides the body with mostly heat and energy.

Starchy roots, tubers and plantain. This group includes plantain (apem, apantu), cocoyam, yam, cassava, kooko, sweet potato. These are major sources of carbohydrates in the Ghanaian diet. They therefore give us heat and energy.

Eating a mixture of these foods gives us good nutrition. Eating only one of these things every day can cause health problems. However, some food is better than no food.

Many children like to eat sweets and sugar. This is fine in small amounts, as it gives us energy. But too much sugar is bad for the teeth because it can cause tooth decay. Too much sugar can also make us fat.

B. Keeping food safely

To keep food safely, there are a number of things you need to think about.

Firstly, foods can go bad or rot. These include most vegetables, fish and meat, but some take longer to go bad than others. They go rotten when they have been left alone too long. When they rot, they start to smell awful, and if you eat them they can make you sick.

To stop fresh food from rotting, it is good to keep it in a cool part of the house or kitchen, away from heat and damp. Another way to stop fresh food rotting is to preserve it. This involves drying the meat, fish or vegetables such as pepper, okra either in the hot sun or over a fire. Fish is also salted and then dried in the sun (koobi).

Secondly, some food, especially food in cans, can go bad if it is kept too long and not stored properly.

Thirdly, some food, especially meat, can make us sick if it is cooked once and then heated up again but not reheated thoroughly. It is best to only cook what you are going to eat on that day. If you do heat up cooked food, make sure it is properly heated through.

Finally, animals including many insects also like food, but if they touch our food they leave germs that can give us diseases and illnesses. Try and keep food away from animals. If you have a box or container to keep it in, this is best.

C. Keeping our surroundings clean

We clean our surroundings to protect us from dirt and diseases. People can get ill from coming into contact with many different things. These include:

- animals and insects;

- rotting food;

- rubbish;

- animal and human faeces;

- chemicals;

- dirty clothes.

For this reason, it is good to clear these things away from where we live, eat or sleep. You can do this easily by cleaning your surroundings every day and collecting the rubbish and dirt in one place away from where you stay.

D. Good and bad hygiene practices

There are many kinds of good hygiene practices you can do every day. The reasons for these are to keep us clean and to protect us from picking up illnesses.

Some good practices include:

- washing ourselves every day if possible;

- cleaning our teeth every day if possible ;

- washing our hands before eating or cooking;

- washing our hands after going to the toilet;

- keeping our house, clothes and surroundings as clean as possible;

- not going to the toilet near the house or kitchen;

- not leaving food lying around in the open.

E. Exercise

Any regular exercise is a good thing, but it is always good to try and make it a habit.

The sorts of exercise that you can do regularly include:

- walking or running to school;

- playing games, e.g. football and netball

- swimming;

- working in the field;

- housework.

It is important to try and do some exercise every day, because it helps build up your muscles, your heart, and your overall fitness. If you don’t exercise regularly, you will find it more difficult when you try to. You will feel weak and short of breath.

Adapted from: Centre For Indigenous Knowledge Systems (CEFIKS)

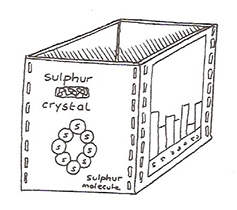

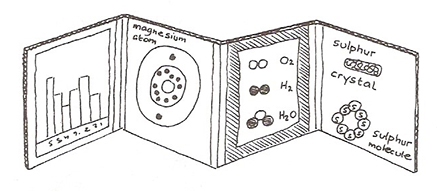

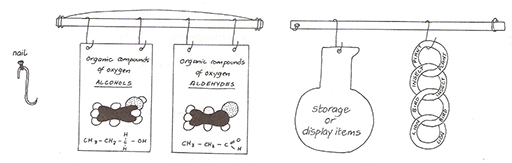

Resource 2: Ideas for classroom displays

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Cardboard box display

- Pin display work on the sides of the box.

- Sew or tape cardboard sheets together to make a box.

- A box can show eight sides.

Display beams and hooks

- Make a beam supported by two nails or loops of wire that can be hung on the wall, or suspended from a fixed beam.

- Hooks or wire allow easy and swift display.

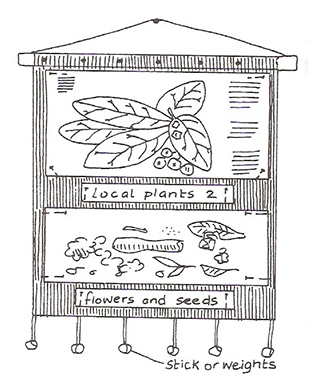

Display charts

- Display charts can be made from durable cement bags, cloth, cardboard boxes, sleeping mats and blankets.

- To make the chart hang flat, attach a strip of wood to the top and either another strip of wood or weights to the bottom.

- Strips at top and bottom will strengthen the chart and make it last longer.

Attach items to be displayed to the chart with office pins, cactus needles or sharpened matchsticks.

Adapted from: Byers, Childs & Laine, The Science Teacher’s Handbook published by VSO/Heinemann

Resource 3: Traditional food storage

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Section 4: Activities to support emotional well-being

Key Focus Question: How can you set up activities to support pupils’ emotional well-being?

Keywords: active learning; building self-esteem; reflective practice; emotional well-being

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- organised different activities to develop and support emotional well-being in your classroom;

- worked in a positive and affirmative manner;

- reflected on your own behaviour in developing your pupils’ emotional well-being.

Introduction

Learning is easier and much more fun if we feel secure and confident in ourselves. By respecting and supporting your pupils in the classroom and planning activities that make them feel included you will support their emotional wellbeing.

1. Teaching children to share

Games are practical activities that pupils can participate in, for fun and for learning. They can also teach pupils how to interact with each other to share ideas and objects. Sharing is important at school because:

- many schools have few resources, and pupils need to use resources in groups;

- pupils have different skills, and sharing encourages them to help each other;

- encouraging sharing and group work means that everyone is learning even if you can’t speak to all of your pupils individually;

- sharing is part of life and we all need to cooperate every day;

- by sharing, people learn how to give support to others and ask for it in return;

- sharing is one way people make friends with each other and it encourages good social interaction.

Here, we are going to look at ideas for sharing activities and how you can encourage sharing as part of your everyday teaching.

Case Study 1: Ways of sharing

Kembabasi is a teacher in a Grade 4 class at a primary school in northern Uganda. She has many children in her class and very few textbooks, exercise books and pencils. So for each reading or writing activity, she organises the pupils into groups to share the resources together.

She plans the activities like this:

- Each group has one textbook or storybook, one exercise book and one pen.

- In the group, one pupil has the textbook and reads it to the others, or they take it in turns and read a bit each.

- One pupil has the exercise book and writes down the answers.

- The other pupils all discuss the questions and answers.

- They all check what has been written down.

- They swap resources after every different kind of activity.

Before the class starts a reading and writing activity, Kembabasi asks each group who is reading and who is writing. This way, she checks that each pupil practises their reading, writing and discussion skills every day, if possible.

The pupils learn how to listen to each other and share ideas. They gain knowledge from each other and learn how to be friends.

Kembabasi changes the groups regularly, so pupils develop new skills and make new friends.

You can find further ideas in Key Resource: Teaching in challenging environments.

Activity 1: A sharing game

This is a game that practises language and sharing.

- Organise your class into three groups.

- Give each person in Group 1 a piece of card with a pronoun written on it (i.e. I, you, he, she, we, they).

- Give each person in Group 2 a piece of card with a verb written on it (e.g. like/likes, go/goes, eat/eats etc.).

- Give each person in Group 3 a piece of card with a noun written on it (e.g. football, home, mango etc.).

- Tell each pupil that they must make a sentence by finding other pupils and sharing their words (e.g. ‘She likes football’).

- Then ask the groups to check if each other’s sentences are correct.

How can you adapt this exercise to teach other topics and subjects, e.g. maths or science?

This flexible, sharing approach can be used with many different topics.

2. Building self-esteem

As a teacher, one of your most important roles is to encourage and support your pupils as learners and people.

An educational psychologist called Abraham Maslow has identified some emotional needs that are important in order to learn well. These include feelings of:

- safety and security;

- love and belonging;

- self-esteem.

Every pupil has the desire for high achievement, which can be measured by self-esteem. Pupils show this in the classroom by being keen to answer questions. If they feel stupid, it damages their self-esteem and discourages them.

However, if you show them their answers might be right or are interesting, it boosts pupils’ self-esteem and encourages participation and high achievement.

You can encourage this in the classroom by being a positive and affirmative teacher. This means:

- being positive and respectful so pupils feel confident enough to contribute;

- making sure that nobody is made to feel stupid or embarrassed when contributing their ideas;

- making sure that everybody understands the lesson’s most important focus.

To do this, you need to develop teaching strategies that do not reject any answer that is given, but you use the pupils’ responses to guide them to think more deeply. By doing this, you will be building pupils’ self-esteem.

Case Study 2: Being a positive and affirmative teacher

Mawuli had been able to encourage pupils in his Primary 5 class to contribute to most lessons through the sharing activities he uses as part of his everyday lessons. The pupils began by making contributions in small groups, and soon were confident enough to start making contributions in front of the whole class.

To make sure he didn’t damage the pupils’ self-esteem, he planned how he would handle their contributions.

- He would ask the class a question. If pupils wanted to answer, they put their hands up and he would choose someone.

- If they gave the correct answer straight away, he would praise them with phrases like: ‘Well done!’, ‘Very good!’, ‘Excellent!’

- If the pupil gave an answer that wasn’t quite right, he was careful not to say ‘No’ or ‘Wrong’. Instead, he would say something neutral like: ‘Almost’, ‘Nearly’, or ‘Not quite’. He might ask the pupil to ‘Try again’ and give them a clue or prompt to help them think a little harder.

- If the pupil was stuck, Mawuli moved on quickly, saying: ‘Can anyone else help us?’

Over time he noticed how much more confident they became.

(See Resource 1: Reflecting on your behaviour for some ideas about how your colleagues can support you in this.)

Activity 2: Building self-esteem

One way to build self-esteem is to help your pupils recognise their own skills.

- Ask your pupils to describe different kinds of things they enjoy doing, both at home and in school.

- Now ask them to think about which activities they are particularly good at.

- Organise them into groups. Then ask each pupil to identify three special skills they have and share these with the group.

- Ask them individually to write about these skills and draw pictures of themselves doing each activity. Display them on the wall.

- In the next lesson, extend this by asking your pupils to discuss what they would like to be or do when they grow up.

3. Creating a caring environment

We have talked about how to help pupils identify and explain their feelings. As emotions are strong reflections of who we are as individuals, they can also make us react in ways that we can’t always control.

Our feelings and behaviour are linked to two things:

- the particular situations we are in;

- our emotional reactions to situations, and our understanding of what is the socially acceptable way to show our feelings.

For example, one of your pupils might be over-excited. Your immediate reaction may be to feel annoyed. But to show this might spoil the good classroom atmosphere. So, to diffuse the situation, you ask her to sit down quietly, or give her a task like giving out books to distract her.

Younger pupils take time to fully understand their emotions and the social rules that say how we should behave. When young, we often experience emotional situations for the first time and don’t know how to react. As we grow older, we learn to understand our emotions better, and to control how we react in different situations.

Here, we are going to look at ways you can encourage this in your classroom.

Case Study 3: Helping each other

Mrs Ameyaw started to work with her Primary 2 pupils to help them understand more about their feelings and behaviour – what made them happy, sad, angry and frightened.

After this, she planned work with her pupils to develop a list of things they could all do to make each other happy and not sad, angry or frightened.