Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 9 March 2026, 5:42 AM

Module 2: Using Community Voices in Your Classroom

Section 1: Investigating stories

Key Focus Question: How can you use investigations to develop ideas about story?

Keywords: research; stories; purpose; questions; investigating; community

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used investigation and research methods to develop your classroom practice;

- investigated pupils’ understanding of stories;

- explored ways to create original stories.

Introduction

Storytelling is an important part of most communities’ life and culture. This module explores how to strengthen links between school and community by using the community and its stories as a resource for learning.

This section introduces you to the value of research in teaching and learning. By setting up research activities, you will find answers to questions, try out new ideas and then use them to create an original piece of work.

1. Developing pupils’ research skills

We all tell stories, about our daily lives or about the past. There are many traditions around storytelling and many lessons to be learned from stories. Activity 1 explores what researching is, how it is done, and how results can be analysed. As you work alongside the class on the task, you will learn what your pupils are capable of.

We suggest that you read Key Resource: Researching in the classroom before starting. If you would like to read about other people’s research, Resource 1: Traditional fables is also interesting. It reports on a workshop, held in Qunu in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, where parents, teachers and pupils discussed the questions you are researching.

Case Study 1: Researching why people tell stories:

Mrs Rashe and her Grade 3 pupils in Nqamakwe, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, tell stories every day.

One day she wrote the question ‘Why do people tell stories?’ on the chalkboard and then listed pupils’ answers:

- To enjoy

- To make people frightened

- To teach me not to do something

She asked each pupil to go home and ask an older person the same question and to bring the answers back. She made sure that she reminded pupils that they needed to approach people very respectfully when asking the question. She also reminded them to explain what the information would be used for.

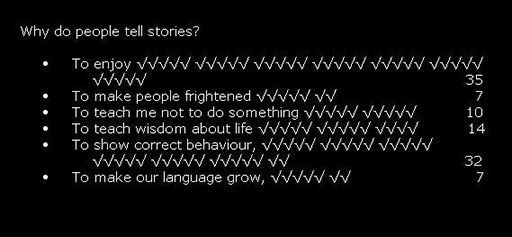

The next day she added their answers to the list. Where more than one person gave the same answer, she added a tick (see Resource 2: Why people tell stories).

She asked the pupils to add up the ticks for each reason. They discussed the following questions:

- Which reasons are the most popular? How do you know?

- Do you agree with the elders’ ideas? Why, or why not?

After the discussion, Mrs Rashe asked her pupils to write what they had found out through their research.

The next day, she asked a few pupils with different views to read their reports. She was very surprised and pleased with the different ideas that the pupils came up with.

Activity 1: Investigating storytelling:

- Explain to pupils about research, using Key Resource: Researching in the classroom beforehand, to help you plan what you want to say. Explain that they are going to help you investigate storytelling. (See Key Resource: Explaining and demonstrating in the classroom.)

- Write the questions from Resource 3: Questions about stories on the chalkboard.

- Explain that each pupil is going to ask these questions of one older person in the community. Remind the pupils to approach the elder respectfully and to record the answers they are given.

- Some days later, divide pupils into groups of six to eight and let them list (for each question), the answers they got, adding a tick where more than one person gave the same answer.

- Now each group reports and you complete a set of data (the information collected by the class) on the chalkboard.

- Discuss the most common ideas. Do the pupils agree with them?

Help pupils to write a simple report on their findings (see Resource 2 for a plan for a research report).

2. Thinking about the purpose of a story

Once you have your research results, they need interpreting so that you can use the information. In this case, this means helping your pupils use this information to understand stories more. Activity 2 helps you to explore meanings in stories as a follow-up to the investigation.

Case Study 2 introduces the important idea of getting pupils to raise their own questions and to try to find answers to them. Being able to raise their own questions in small groups builds independent thought and develops pupils’ ability to think creatively and critically.

Case Study 2: Finishing a story

Mrs Ofori from Suhum in the Eastern Region did careful research into the details of a good, but not well-known, story (see Resource 4: How Mrs Ofori found her story).

One day, she gathered her Class 2 pupils around her, and told them the first part of the story (the first three paragraphs of Resource 5: The river that swept away liars). Next, she asked them to each think of a question about what would happen in the rest of the story. After two minutes, they gave her their questions, and she wrote them on the chalkboard.

She asked the class to think of answers to the questions, taking each question in turn. The pupils gave reasons for their answers.

After they had gone back over all the questions and answers, she asked them to help her write an ending for the story. They suggested what might happen next and she wrote their ideas on the board. She did not rush the process, or push her ideas on to the pupils.

Once the story was complete, they read it together.

The pupils liked working together on the story. The next day, in pairs, they drew pictures for different parts of the story. These were put together in a book.

Finally, Mrs Ofori read them the original story. The pupils were pleased at their ending compared to the original and talked a lot about the problems of telling lies.

Activity 2: Discussing why specific stories were told:

- Choose a good story from those that you know. Make sure that you have a complete version of the story.

- Make one copy of the story for each group in your class, or write the story on the chalkboard, where they can all see it.

- Also write up the reasons for storytelling that came out of the class research.

- Ask your pupils to discuss in groups why they think people would have told this story (i.e. its purpose).

- As groups report back, ask them to explain their reasons.

- Next, discuss the characters in the story and their behaviour.

- Ask the pupils how they could apply this story to their own lives.

- Ask them, in groups, to discuss the purpose of another story, perhaps one from home and then to draft a paragraph about the story’s purpose.

Did they all understand the purpose of their stories? How do you know this?

- This activity need not be completed in one 30-minute lesson period. It can be spread to other lesson periods if your pupils have lots of ideas to discuss.

3. Writing stories

Research suggests that people learn best when what is being taught is relevant to them. As a teacher, you constantly need to make sure that your pupils are gaining knowledge that will help them make sense of their world.

You and your class have researched why people tell stories, and looked at the meanings of particular stories. Now we look at how you can help your pupils apply storytelling to real-life situations and difficulties.

Case Study 3: Writing a story

Mr Okoe wanted to help his pupils in his Class 3 at Amasaman, near Accra, to write their own stories in pairs. He wrote a list of possible story features (see below) on the chalkboard and discussed with his pupils how these can determine what kind of story is written.

- Animals representing humans

- Marvellous events, unusual creatures

- Someone getting into difficulties and finding a way out

- Good and evil

- Explanations for the way things are

He also gave them a list of events, good and bad, that had happened in the city recently and suggested they use one of these as the context of their story. Next, he asked them to choose whether the characters in their story would be animals or people. Finally, he asked what theme they might choose, such as the battle between good and evil. Once they had decided, he encouraged each pair to start writing.

Over the next week or two, Mr Okoe asked each pair to share their story with the rest of the class who then discussed what the story’s purpose was. He was very pleased with the variety of the stories.

Key Activity: Creating an original story:

Ask pupils to think of problems in their families, school and community that come out of the way people behave towards one another. The problems might range from everyday ones, like laziness, to serious issues, such as HIV/AIDS. You might prompt them by describing familiar situations involving certain kinds of behaviour, but be sensitive to the situations of individual pupils in your class. You could use old newspapers and magazines to help with ideas for stories.

- Each group should choose one problem to create a story that shows the effects of this kind of behaviour and offers some wisdom about it.

- Discuss some of the features of stories before they write their story or plan how they will tell it (see Case Study 3).

- Ask each group to tell their story to the class. Discuss the purpose of each story, list these, and compare them with their research findings from Activity 1.

- Let group members decide for themselves whether their story was successful, and why. (See questions in Resource 6: Assessing your story.)

How well did they assess themselves?

Do you agree with their assessment?

- If you have younger pupils, you may want to do this as a whole-class activity where you write their ideas on the board or on paper.

Resource 1: Traditional fables

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background

A workshop was held as part of the work of the Nelson Mandela Foundation’s Unit for Rural Schooling and Development, with five schools from the Qunu area of the Eastern Cape participating. From each school, there were two teachers, one pupil, one parent, and one member of the school governing body.

The aim of the workshop was to reflect together on the value of traditional fables in the education of young people, and the community, and to plan a way forward for making use of these stories in and out of school.

What follows is a report on a discussion that was held in groups on the first day of the workshop. Participants reported back on their ideas.

Do you agree with their ideas and comments?

What is a fable?

A fable is a short story with a specific aim. It has some teachings, humour, warnings. It applauds, criticises and corrects. It sharpens the mind to think critically and creates a deep thinker. Some were real events, which, over time, turned into fables; some have been specially coined for conscience pricking, in order to relive the past event and to teach modesty.

Who are the people who tell, or told, fables?

Unanimously they said it was the elderly – grandmothers and grandfathers, also children among themselves, during initiation schooling of both girls and boys. Also teachers, radios and television told stories.

To whom did/do they tell them?

They were told to children, youth and the elderly.

When and where are/were fables told?

The common room was mostly used, sometimes the bedroom, and sometimes stories were told while basking in the sun near the cattle enclosures. Other places were the riverbank, the grazing lands, field watch-house and initiation places.

Why were/are they told?

They were for enjoyment, for sharpening the mind, as reminders, as a deterrent or warning, to encourage patriotism through certain behaviours, to pass on vocabulary and its intricacies (like figures of speech, idioms and proverbs and new words which enter the dictionary).

How are/were they told? (Style of delivery)

There was competition in storytelling. It was an art, involving music, humour and changing the voice. A traditional fable has a unique beginning and ending.

Are new as well as old fables told? For what reasons are new ones created?

Old and new fables are being used, and they do the same work. The new ones encompass new angles of life.

Do you have any written versions of fables? Name them.

There are very few old fables out there in written form. (Some were named.)

What was observed is that very few fables were remembered by the group and it was not easy to do so. Only one person remembered three; some couldn’t remember any. From 23 participants, only 19 fables came forward. What does this mean?

Where and how are written fables used?

Fables are read from books over and over again. The same happens at home where the same fables are repeatedly told for enjoyment. At school they are read to children. They are of great help to children’s vocabulary. They are few. There are some in libraries and sometimes they are acted on stage.

The language used

The commonly used language is the regional dialect. Baby-language is also used, as well as words coined to show respect.

Taken from: report of workshop on traditional fables, held at Qunu, Eastern Cape

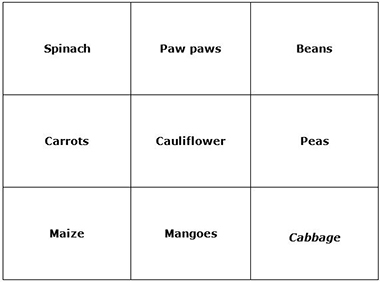

Resource 2: Why people tell stories

![]() Example of pupils' work

Example of pupils' work

Mrs Rashe’s chalkboard

Plan for research report

Research question

What we did

How we analysed data

What we found out

Report on story research

The Grade 3 pupils asked elders a question: ‘Why do people tell stories?’

35 elders answered the question.

The pupils made a list of all the answers, and counted how many people gave each answer.

Example report

34 people thought that stories are told for the listeners to enjoy them.

32 people thought that stories are told to show correct behaviour.

14 people thought that stories are told to teach wisdom about life.

10 people thought that stories are told to teach people not to do something.

7 people thought that stories are told to make language grow.

7 people thought that stories are told to frighten people.

Resource 3: Questions about stories

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

1. Who are the people who usually tell stories? 2. To whom do they tell them? 3. When and where are stories told? 4. Why do people tell stories? 5. How do they tell them? (Style of delivery) 6. Are new as well as old stories told? For what reasons are new ones created? |

This resource is suitable for use with older pupils. For younger pupils, you may want to choose one or two of these questions for your pupils to investigate.

Resource 4: How Mrs Ofori found her story

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Mrs Ofori tried to find a good story that she could use in her class. She knew the adage that ’nobody is more important than another person’. However, she could not remember the story that goes with that adage. She remembered the story was about and uncle and a nephew. She also remembered that there was a river they had to cross.

Since she could not remember the full story, Mrs Ofori asked her friend, Abigail, whose father is a storyteller on the local radio station. Abigail knew about the story but she could not give the details. When Abigail went home, she asked her father, Mr Owusu, if he remembered the details of the story. Mr Owusu told Abigail that the story came about because the inhabitants of a small town in the Ashanti Region were tired of a young man who was always telling lies and exaggerating issues to make people feel he was very important. Mr Owusu’s version of the story is at

Taken from: Umthamo 2, University of Fort Hare Distance Education Project

Resource 5: The river that swept away liars

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Once upon a time,

time, time [this is the opening pattern that precedes all Ghanaian stories when the stories are told in English].

A certain wealthy cocoa farmer was on a journey with his young nephew from Awisa in the Eastern Region to Berekum in the Brong Ahafo Region. You remember that in those days there were no cars, so they walked. It was a long journey, so it took them many days – walking in the forest, crossing rivers, listening to different animals and sharing stories. Whenever they got to a village on the way, they would rest for a while or sleep overnight and continue their journey the next day. As they were going on their journey, travelling across the country, the wealthy farmer saw a fox crossing their path.

The wealthy farmer remarked, ’That fox is quite big.’ The nephew replied, ’Oh, Uncle, this is nothing compared to the one I saw yesterday.’ ’Is that so?’ responded the uncle. ’Oh yes. It was very, very big. In fact, it was as big as an ox!’ ‘As big as an ox?’ questioned the uncle. ‘Yes, as big as an ox,’ answered the nephew. The uncle answered again, ‘You say ”as big as an ox”?’ ‘Yes, really, as big as an ox,’ said the nephew. The uncle did not utter a word and they continued on their way, without talking to each other, for about an hour.

The nephew noticed that his uncle was not happy and he didn’t know what was worrying him. So he asked his uncle what the matter was. His uncle told him that they would have to cross four rivers before they reached their destination. The last river was the biggest and the most dangerous of all the rivers. This river was allergic to liars, and no liar could escape its wrath. It swept liars there and then down to the bottom of River Tano. It never missed a liar, even if he were to use a talisman for protection against evil spirits.

When the nephew heard this, he was quite shocked because he knew how powerful talismans were and if this river would not yield to any talisman then he knew it must be a VERY powerful river. As they travelled, the nephew became more and more uneasy. The uncle also became sadder and sadder the further they walked. And as the uncle grew sadder, the nephew grew more and more panic-stricken.

As they neared each river, the size of the fox changed. When they reached the first river, the nephew said, ‘Uncle, the fox was not exactly as big as an ox. It was a little bit smaller than an ox.’ The uncle did not remark.

When they reached the second river, the nephew said, ‘The fox was not even nearly the size of an ox. It was as big as a calf.’ But again, the uncle did not remark. When they had crossed this second river, the uncle just explained his concerns about the last dangerous river, and said no more.

As they approached the third river, the nephew said to his uncle, ‘The fox was not even as big as a calf. It was as big as a goat.’

Just before they reached the last river, the fox was the same size as other foxes, which are common everywhere.

That is why our elders say ‘Don’t try to be important among your colleagues. Everybody has something to share. You don’t need to exaggerate things in order to be important.’

Adapted from: Umthamo 2. University of FortHare Distance Education Project

Resource 6: Assessing your story

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Questions

1. Did the class enjoy your story?

2. How do you know?

3. Did the class learn something from your story?

4. How do you know?

5. Did your story give its message clearly? 6. How do you know?

|

Section 2: Ways to collect and perform stories

Key Focus Question: How can you use performance to develop your pupils’ language skills?

Keywords: stories; collect; perform; confidence; competence; pride; cultural heritage

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- worked with your local community to promote language skills and pride in cultural heritage;

- planned and organised opportunities for performance before an audience.

Introduction

Using different kinds of oral activities can develop your pupils’ confidence in speaking and listening and promote pride in their home languages. This will have a positive impact on their self-esteem. Pupils who feel more confident about who they are will learn more easily.

The activities in this section provide opportunities for your pupils to collect, rehearse and perform stories in front of an audience. It is suggested that you work with older community members by asking for their help in providing stories and in sharing their storytelling skills. These activities will build competence in the home language, on to which you can later build additional language skills.

1. Sharing stories from the community

Community knowledge of stories is a valuable resource for listening and speaking activities outside and inside the classroom. It is important that your pupils learn to respect and love the wisdom and heritage of their home language and culture. By strengthening their speaking and listening skills in the home language in an enjoyable way, the pupils will grow in confidence too.

Because the art of storytelling is no longer so deeply valued in some communities, people may have forgotten some of the richness and detail of stories. A way of building language resources for your class is to uncover older and more authentic versions of stories. You can do this by talking to other people in the community.

Case Study 1: Using the multilingualism of your class

Mr Kimaryo teaches grade 4 at Makanya Primary School in Tanzania. The school is near a sisal estate, where workers speak many different languages. In his class of 70 pupils, 10 speak Chaga, 6 speak Chirundi, 3 speak Chinamwanga, and the rest speak Pare. He usually speaks Swahili when he teaches them.

Mr Kimaryo wanted his pupils to collect stories from their homes and to build their confidence in speaking by telling stories in their home languages. He began his lesson by showing pupils a picture of an old man and some members of the family seated around the fireplace. He then asked the pupils in pairs to discuss what the people were doing. The pairs reported their answers to the class. He then asked the pupils if they also sat around the fireplace to listen to stories, and many said they didn’t. He told the pupils to go home and ask one of the older members of the community to tell them a story.

In the next lesson, he divided the pupils into groups. He made two groups of Chaga speakers, one group of Chirundi speakers and one of Chinamwanga. He divided the Pare speakers into ten groups. He asked each pupil to tell their story to the rest of the group members, using the home language.

Mr Kimaryo went round and listened as they told their stories. He was pleased at how well they told the stories, especially the ways they used their voices to add interest.

Activity 1: Sharing stories in the home language

Your pupils have found out what older people know about storytelling in Section 1. Now is the time for them to collect stories from them.

- Talk to your pupils about their experiences of listening to stories, and find out what kinds of stories they enjoy. Ask them whether they listen to stories at home, and who are the storytellers in their community.

- Ask them to find someone from the home community to tell them a story. They will need to remember the story because they will have to tell it to their classmates. A good way of learning the story is for them to tell it to a number of people at home. As they do this, they should check that they have all the details of the story right.

- In the next lesson, group together pupils with the same home language (see Key Resource: Using group work in your classroom). Ask them to tell each other the stories they collected, using their home languages.

How did your pupils react to this activity?

How could you build up a resource of these stories?

2. Inviting visitors into school

Inviting community members into the classroom will help to motivate pupils and build their storytelling expertise in the home language. You can also ask your visitors to offer their knowledge of stories, to make sure that the stories the pupils tell are as complete and authentic as possible. This will mean that these stories become a rich resource for learning.

If you have a large class, this kind of community support is particularly helpful. Asking for support from your head teacher and colleagues may make it easier to get some members of the community involved on a regular basis.

Case Study 2: Inviting community participation in an Open Day

Four teachers at TsitoPrimary school in the Volta Region were all enrolled in the same NTI distance learning teacher upgrading programme. One of the modules asked them to explore how resources around them could be used in the classroom. They did some work on collecting boxes, bottles, plants and other resources and using them in science, mathematics and language activities. But the module reminded them that people are the most valuable resource for learning. It suggested that they arrange an Open Day for pupils and older community members to share their knowledge and skills.

The day the four teachers organised was a great success. Mrs Dogoe, the Parents–Teachers’ Association chairperson, told the history of the school. Some older community members demonstrated crafts, such as basket weaving, tobacco curing, and beadwork, and women renowned for their cooking gave recipes for traditional dishes. Various grandfathers and grandmothers told Ananse stories (traditional tales).

Then it was the turn of the pupils to demonstrate what they had learned at school. The day ended with the performance of songs and dances by different groups.

As a result of the activities of the day, several community members became regular visitors to the school. They passed on their skills in various crafts and told stories, which were later used in class.

Activity 2: Coaching from community ‘experts’

You will need to plan this activity well in advance and allow a whole morning or afternoon for it.

- Arrange your pupils into groups of the same home language. Ask each home language group to invite someone from their community to class to help pupils with their storytelling skills. Give each group a written invitation to take home (see Resource 1: Sample invitation letter).

- On the day, ask the community members to join the group and listen to the pupils telling stories. Ask the ‘experts’ to give the pupils guidance and advice on how to improve the stories and their storytelling.

- Once the ‘training’ part is over, groups can come together and listen to stories from the experts. Songs, poems and riddles could also be shared.

What did the community participation add to the learning in your classroom?

Were you pleased with the way you organised your activity?

- What would you do differently next time?

3. Performing for an audience

It is important that every pupil is able to communicate effectively and is given the opportunity to be imaginative. Group story performances can give even quiet pupils the chance to speak, sing, act, dance, etc. without too much pressure. Each pupil in a story-performing group can play a role: a character in the story, a narrator or part of a chorus. Pupils with specific talents can create ‘props’ and ‘costumes’ with objects such as pieces of cloth or paper or a few twigs from a tree.

In classes where pupils do not all speak the same home language, working with fellow speakers of the same language in order to prepare a performance in this language can be very positive.

This next part provides you with ways to develop pupils’ confidence and skills in speaking their home language. These ways can also be used to improve skills in a lingua franca or an additional language.

Case Study 3: A story performance day with a large class

Miss Afi Yakubu teaches a class of 80 Class 5 pupils in a village near Yendi in the Northern Region and decides to hold an end-of-term story performance day. She organises her pupils into groups of five and then encourages them not just to tell stories but also to perform them so that both performers and audience will enjoy them. She tells pupils that if they wish to perform in a language that not everyone knows, they must decide how to help the audience understand the meaning by using actions, facial expressions and different objects (‘props’).

Miss Yakubu gives her pupils time to plan and rehearse their chosen stories. As they work, she monitors their progress and sometimes shortens or lengthens the preparation time. She has found that pupils prefer to prepare and perform their work outdoors.

With 80 pupils, it would take up too much time if all groups performed for everyone in the class. On the story performance day, Miss Yakubu asks pupils to form four circles, with four groups in each circle. She numbers the groups in each circle from 1 to 4. Group 1 performs in the circle centre for groups 2, 3 and 4. Then group 2 performs for groups 1, 3 and 4 and so on until all groups have had a turn.

After the performances, Miss Yakubu asks each group to discuss what they have learned. She thinks about what some of the quieter pupils in her class have shown about their understanding and how she can use this information to plan the next stage of learning.

Key Resource: Working with large classes gives further ideas for teaching large classes.

Key Activity: Performing stories for an audience

Ask pupils to form themselves into groups of six. Ask them to:

- think about the stories they have told and listened to;

- decide which story they think would be the best one to perform for the rest of the class, so that everyone can understand and enjoy it – more than one group can choose the same story;

- identify all the characters and decide who will play each part. They may also need a narrator;

- decide on the language(s) to use, sound effects, gestures, clothes and objects that will help bring the story to life and who brings which resources.

Allow time to rehearse and set a time limit for the performance. Monitor each group and help them as necessary by providing ideas or suggesting ways to do things.

Ask the audience to give feedback to each group (see Resource 2: Assessing group story performances).

If you can, tape-record the stories that are performed. Otherwise, take notes for later use.

- The stories could be perfected and performed to parents and community leaders in your area to raise funds for buying resources for your class.

Resource 1: Sample invitation letter

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Dear …………………

Our class, Class 5, is learning about local stories and the art of storytelling. We have heard about your expertise and we would like to invite you to come and help us work on how to develop our storytelling skills and to help us learn the stories well.

We would like you to come on …………………………………. Please let us know if this is convenient. ………………………………… from our class will meet you at the school gate at 10.00 am.

With many thanks

Class 5 Pupils

Nyogbare Primary School

Resource 2: Assessing group story performances

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

| Performance feature | Excellent | Good | Average | Weak |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy to follow and enjoyable story | ||||

| Use of different voices | ||||

| Use of sound effects | ||||

| Use of movement | ||||

| Use of costumes and/or props |

Section 3: Using local games for learning

Key Focus Question: How can you use local games to help language learning?

Keywords: reflection; research; local games; traditional; rhymes; songs; investigating

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used traditional and local games to support learning activities;

- motivated pupils and built their confidence in using language through games, songs and rhymes;

- extended your own skills in thinking about your role and effectiveness by investigating the value of games for learning.

Introduction

Some teachers who have taught for 20 years have only one year’s experience, repeated many times. This is because they do not learn much or do not develop into better teachers.

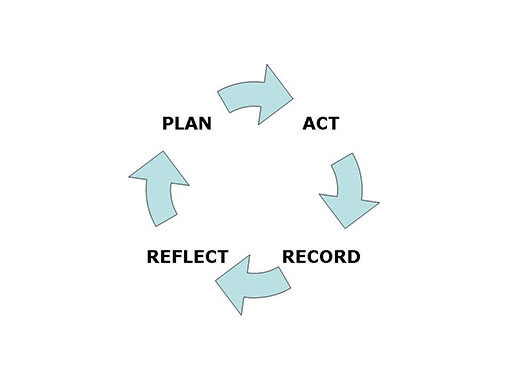

Good teachers plan what they do and, once they have done it, record what happened, ask themselves what was successful and what needs improvement. They reflect on (think about) whether the pupils learned anything and, if they did, what they learned. On the basis of this ‘reflection’, they plan again for their next activity. Resource 1: Action-reflection cycle shows this process in the form of a diagram

1. Informal learning

Children do not only learn in the classroom; they also learn while they are playing. They learn from one another, by watching what others do. They learn by talking, singing, chanting and interacting. By can use play to make your classroom learning more effective and close the gap between what happens in the classroom and outside.

In Activity 1, your pupils act as researchers, going out into the playground (or beyond) to record what they think children are learning there. When they come back into the classroom, they will talk about what they found out: you will be able to listen to their talk and see what you think they have learned.

Case Study 1: A six-year-old learns and teaches English

Six-year-old Maria is at a school where English is the language of the classroom, although it is not her home language.

Every day for a week, Maria could be seen at break time watching other children play with a skipping rope. She did not join in, but stood close enough to watch and to ‘listen in’ to the rhyme the children were chanting. On the first day of the second week, Maria took her usual position a few feet away from the game, but now she could be seen ‘sounding out’ the words of the rhyme.

‘Juu-ump, Juuu-ump in and saaay

One-un, two-ooo, threee,

Juu-ump in wi-th me.’

She repeated these words over and over, taking delight in saying them louder, softer, and with different stress on parts of a word. She repeated the rhyme several times and then listened again to the other children. She smiled, and said the rhyme again. Finally she looked for a rope and went to her friend, Miguel. She sang the song, line for line to her friend, teaching him the song. She translated the English words so that he could understand what he was learning. Soon Miguel was able to sing the rhyme with Maria.

Activity 1: Investigating natural learning:

Before you start this activity, read Resource 2: Research on local games in the curriculum. This explains one researcher’s work and two games that the teachers developed as a result of that research. It would also be helpful to read Key Resource: Researching in the classroom.

- Talk to your pupils about learning. Do they know that they are always learning: at home, at school, when they are playing?

- Ask the class to do an investigation into ‘natural’ learning. Their question is: What learning happens when children play? The pupils should make notes and drawings about the learning they see in the playground and after school, when other children are playing, and when they play themselves.

- In class, ask pupils to share their findings, in groups. Ask each group to demonstrate how to play one game. Record songs or chants they sing during the game, on tape, or in writing.

- Ask each group to discuss what can be learned from these games. Note down their ideas.

What did you learn from this activity about how games can help learning?

2. Learning from games

All sorts of games can be used for learning and you need to think creatively about how to use them in the classroom (see Activity 2). It helps if you can work together with colleagues and friends, and also with your pupils, creating new ideas that can make the learning in your classroom more fun and effective.

In this part, you and your class extend your research investigations by asking older members of the community about games that they played when they were young.

Case Study 2: Games and chants on reading cards

The Ghana Institute of Language (GIL) promotes additive multilingualism, i.e. basic learning in the mother tongue language, with other languages added (without replacing the mother tongue language). The curriculum aims to include all languages that children know in their schooling.

Miss Arthur helped her Class 3 pupils in CapeCoast to make ‘reading’ cards, one for each pupil in the class. They drew a picture of themselves on one side of a piece of card. On the other side, they wrote songs, games, chants or rhymes, which they brought from home.

Each day, they have a reading period when the pupils read (and sing!) the cards. Sometimes, a better reader reads a card with a slower reader. Sometimes, a speaker of one language helps another pupil to read their language and make the sounds. Sometimes, they act out the rhymes or play the games. Miss Arthur has noticed how much happier her class is and how they mix much better since doing this.

Activity 2: Games and songs from older community members:

- Ask your pupils to ask an older person (parent, grandparent, neighbour, etc.) to teach them a game, song or chant they used to enjoy. They need to know the rules or words and any resources it might need.

- Next day, list the games and songs that pupils brought from home.

- Group together pupils who learned the same game or song. Ask them to prepare to teach this game or song to the class.

- Ask them to write out the song or chant or how to play the game on a card.

- When the class has learned the game or song, discuss what can be learned from it. Make notes as you did before.

In future lessons, encourage pupils to read newspapers and magazines to find songs, games, riddles and jokes as a basis for writing their own.

3. Using reflection to improve teaching

‘Reflection’ is thinking over what happened and seeing how you could do it better next time. After you have tried new activities, it is really helpful to reflect on what was successful and what needs improvement. Make the process of ‘Plan-Act-Record-Reflect’ a part of your daily practice (see Resource 1).

Now that you have a good collection of games, you can use them as the basis for learning activities, and as a basis for reflection and growth. (This can, of course, be done with stories as well.)

Resource 3: Word games has some word games you can try with your pupils.

Case Study 3: English verbs in a skipping song

Mrs Osei-Asante sang a skipping song when she was a child in Kumasi. She decided to use it for teaching her Class 2 pupils some words and present-tense phrases in English.

The pupils first sang it in Twi and then she helped them to sing it in English.

She gave each pupil a piece of paper with a verb (e.g. eat, drink, laugh, cough, jump, run, hop) written on it. She made sure that each child knew what the word meant and how to do the action associated with it.

She allowed each pupil in turn to mime their action, and the class sang a new verse: Akosua, what is she doing? Akosua, she is laughing,’ etc.

After the lesson, she thought about:

- what went well;

- what didn’t go so well;

- what surprised her;

- what she would change if she repeated the lesson.

What surprised her was how much time it took for the pupils to learn the English version but also how much the children enjoyed it. She decided that she needed to give more time to the activity, and introduce fewer new words at a time.

The following week, she used the English version of another skipping song in a similar way, making verses with different kinds of foods.

Key Activity: Learning from a chant, song or game:

- Is there a chant in your class collection that could be changed into the additional language and used to support language learning?

- Identify a sentence in the chant where a word (or words) could be replaced by a number of other words in turn. For example, ‘She is laughing’ could be replaced with ‘She is jumping, hopping, running’ etc. Each pupil, or group, can then sing a new verse, with a new word in the sentence.

- It will be even more fun if the words or sentences can be linked to actions.

- Plan how you will organise your class to sing/chant and act out this ‘substitution drill’. (This is a series of sentences, which are the same except for one word/phrase; they are used to practise language patterns.)

- If it is not successful, you will need to try a different song, or a different way of organising the activity.

Using a mini-drama may make the entire activity more interesting and fun.

Resource 1: Action-reflection cycle

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

The diagram shows the following steps in the action-reflection cycle:

- Plan an activity.

- Act by putting the plan into practice, and observe how it goes.

- Record what you observe.

- Reflect on what happened.

- Revise your plan, or make a new plan.

- Put the revised or new plan into action, and observe again.

- Record and reflect again.

- And so on, and so on …

Everything you do as a teacher can become part of an action-reflection cycle. Record your thoughts and ideas; writing ideas and thoughts down can help.

For example, Mr Abeeku wanted his class to try some shared reading activities (reading where the pupils read to each other and help each other).

Plan an activity – Mr Abeeku planned to divide his class into groups of five and to make sure that each group had some reading material. They were then to take it in turns in their groups to read out loud to each other. They would help each other when they got stuck and only ask him for help if they were really struggling. He would get on with some marking while they did this.

Act by putting the plan into practice – Mr Abeeku tried this in a single lesson one morning.

Record what you observe – The groups were the right size, but he observed that it took a long time for them to understand what they had to do, and they kept asking him for instructions. However, when they did understand, it seemed to work very well with most of the groups. He saw that two boys and one girl were too shy to read.

Reflect – He decided that the activity was a good one but that he needed to organise it better. He thought that there were at least three pupils who needed some more help from him with their reading. There were some words that were new to the whole class.

Revise your plan, or make a new plan – Next time, he would write simple instructions on the board so that they did not have to keep asking him for help. He decided not to use the time to mark but to go around listening and assessing informally the skills of his pupils. He revised some of the difficult words with the whole class.

(See also Key Resource: Researching in the classroom.)

Resource 2: Research on local games in the curriculum

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Nonhlanhla Shange is involved in research towards her masters degree at the Nelson Mandela Unit for Rural Schooling at the University of Fort Hare in South Africa. She is researching the use of local games in the classroom, working at four rural schools.

The pupils and their teachers are carrying out action research into local games.

Teachers listen attentively and make notes of the games that are brought by pupils to class. They try to develop lessons based on the games. They keep journals, in which they reflect on how successful these lessons are, and try to improve on them with future attempts.

Descriptions of two games that were played as part of the research are below.

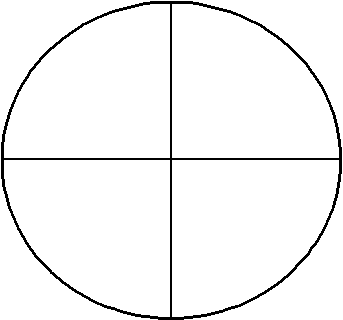

1. Circle game

Preparations for the game involve drawing a diagram like the one below on the ground..

How is the game played?

This game is played by small groups of five or six pupils. One pupil jumps inside the spaces, turning from side to side, while the other pupils sing a short song or rhyme, first in the local language, and then in English.

What learning activities were based on this game?

This game was developed to show how using repetition, in the children’s own language and in English, can aid learning. By using a different short song or rhyme, the game was also used to teach and practise pupils’ counting.

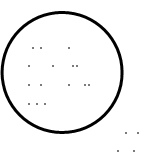

2. Stone game

Preparations for the game involve drawing a circle on the ground and putting a number of stones in the circle. (The circle should be no more than a metre in diameter.)

How is the game played?

Pupils are put into small groups of five or six. Each group has its own circle on the ground with stones inside it.

A player throws one stone up; before it falls to the ground, they must try to pick up other stones from within the circle.

Every pupil in each group should assign themselves a number (below 10). This number is the number of stones that the player has to try and pick up.

One player goes first. If the player picks up the required number of stones from the circle, they say the multiplication table of this number (for example, the 3 times table, stopping at 30 – this could be lower for younger pupils).

If a player fails to pick up the required number of stones from the circle, they have to multiply the number of stones they have picked up by the number of stones they were supposed to pick up, and come up with a correct answer. For example, if they were supposed to pick up 5 stones, but only picked up 3, they would have to give the correct answer to the sum 5 x 3.

The other players will judge whether they are giving the right or wrong answer.

What learning activities were based on this game?

This game was used to practise pupils’ skills at multiplication.

Taken from: Shange, N., Nelson Mandela Foundation’s Unit for Rural Schooling and Development [unpublished research

Resource 3: Word games

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

These games can be played in any language and with any age, provided pupils are moderately competent in literacy skills.

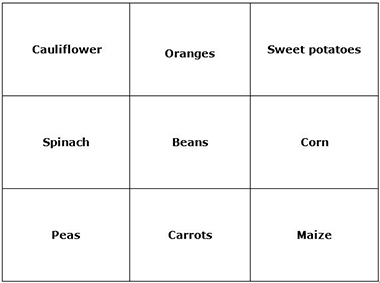

Game 1: Bingo

Read the pupils a story they enjoy and ask them to choose two words they like.

Ask each pupil for their words and write the key words on the chalkboard where everyone can see.

Divide the class into groups of six and ask each group to choose 12 words for their group. These can be different for each group.

Each pupil makes a bingo sheet by drawing a big square divided into nine small squares (see example below).

Tell each pupil to choose any nine words from their list of 12 and copy these into the bingo sheet, one word in each square. Pupils’ sheets will be different, because they can only choose nine out of the 12 words.

One pupil has the master sheet with the 12 words. They call the words out in random order. As a word is called out each pupil who has the word must cross it out from the bingo sheet. The first to cross out all their words shouts ‘Bingo’ and has won.

Let each group play again with each pupil taking a turn at calling out the words.

If you want to use the bingo sheets more than once, ask the pupils to cover the words with stones or counters as the words are called out.

Did the pupils learn new words? How do you know this?

Sample list of words for Bingo:

Beans

Cabbage

Carrots

Cauliflower

Corn

Mangoes

Maize

Oranges

Paw paws

Peas

Spinach

Two examples of bingo cards:

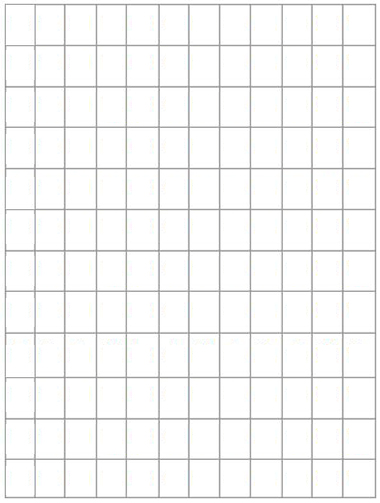

Game 2: Word soup

Make a list of nine words, e.g. parts of the body, rooms in a house, or vegetables. Put this list on the board (next to pictures illustrating the words if you can).

Give each pupil a sheet of squared paper. Tell them to enter the key words into the squared paper, one letter per square. Tell them that words can go from left to right, or top to bottom. Tell pupils to fill the extra squares with any letters of the alphabet. (See example below.)

When every pupil has done this, collect the sheets and mix them up. Now distribute them randomly, and ask pupils to circle all the key words they can find. Each pupil knows there must be nine. The first to finish is the winner.

The pupils can then choose their own subject or area and a word soup from this to give to a friend to play.

Words to find in this word soup:

Bedrooms

Balcony

Sitting room

Staircase

Window

Kitchen

Door

Floor

Ceiling

You can make this more interesting by giving ten words and asking them ‘Which word is NOT included in the soup?’ You can use this game for lots of different words and in different subjects.

A blank template for word soup is below. You can add more squares or make it smaller to make the game harder or easier depending on the age and ability of your pupils.

Make a list of nine words, e.g. parts of the body, rooms in a house, or vegetables. Put this list on the board (next to pictures illustrating the words if you can).

Game 3: Pilolo

In Ghana, there are a lot of children’s folk games.

’Pilolo’ means ‘Time to search for’. The game needs about four players, including the timekeeper and leader.

Before the game starts, the timekeeper has to stand at the finishing place or end point. The leader will also be with the other four to make sure that no one moves from where he or she is supposed to be.

The leader will hide sticks or stones in palm trees, in the sand or in other places. Then the leader will come and announce ’Pilolo’, while the timekeeper starts his or her watch. The other players have to find one of the sticks or stones and run to the end point as quickly as they can. The person who is quickest and reaches the end point first is the winner of the game. The game can be repeated several times to find out the final winner.

This game helps children in Ghana in many ways. It helps them to be physically fit, mentally alert and emotionally sound.

You could adapt this game by hiding word cards in various languages.

Taken from: http://www.gameskidsplay.net/ games/ chasing_games/ pilolo.htm (accessed 03/07/07)

Resource 4: Skipping song

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Igbo skipping song

Ikuku buru gi

Zamiriza

Buru gi buru nwa nnegi

Zamiriza

Nwa nnegi idobere na ukwu osisi kporonku

Chọ ya ịhuyi ya (2x)

English translation

Let the wind blow you

Zamiriza

Blow you and your little sister

Zamiriza

The little sister you left under a tree that shed all its leaves

Look for her, you cannot find her (2x)

Section 4: Using story and poetry

Key Focus Question: How can you use poetry and story to stimulate pupils to write?

Keywords: name; praise; poems; stories; biographies, writing

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used name or praise poems or stories to stimulate pupils’ ideas for writing;

- used resources such as magazine or newspaper articles to stimulate ideas for writing life stories (biographies);

- explored ‘drafting’ and ‘crafting’ when writing.

Introduction

Throughout Africa, we have a rich oral and written literature about people who are, or who were in the past, important to their families, their communities and their countries. They are celebrated in praise songs and poems and in life stories (biographies). Using this rich cultural history in your teaching can provide reading materials for the language classroom and stimulate pupils’ interest in writing.

1. Using poems to stimulate writing activities

If pupils listen to and read poems or stories that they enjoy, they are more likely to be interested in developing their own reading and writing skills in their home language or in the language of the classroom.

In order to become successful writers, pupils need several ‘tools’. Firstly, they need something to write about. In Activity 1, you will use examples of name or praise poems or stories to give pupils ideas. Then you will guide them in writing the first draft of a name or praise poem or story. It is important for pupils to understand that writers ‘craft’ their poems and stories. This means writing several draft versions, to which they make improvements, until they are satisfied that their poem or story is the best they can make it.

Case Study 1: Reading and writing name poems and stories at a teacher workshop

At a four-day workshop in Johannesburg in South Africa, some teachers of English read poems and stories about names. In these, the writers described how they came to have their names, what they liked or did not like about them and what words or images they associated with them. The teachers really enjoyed what they read and asked if they could write their own name poems or stories during the workshop.

On the second day, each teacher read his or her first draft to a partner. They gave each other feedback on what they liked and what they thought could be improved, for example by adding details and choosing different vocabulary or punctuation.

On the fourth day, having worked on their drafts the day before, they each read their completed poem or story to the whole group. There was laughter, there were some tears and there was much applause.

When they were asked to reflect on their experience, they said:

- no one had been ‘stuck’ for something to write about;

- while most wrote in English, they enjoyed using occasional words or phrases in an African language to express a particular idea;

- they benefited from the feedback on their first draft;

- they felt proud of the final version;

- they enjoyed listening to the other stories/poems;

- many of the poems were similar to traditional praise poems and songs.

The teachers decided they would read their own and other name poems or stories to their pupils and help them to write about their names.

Activity 1: Drafting name or praise poems or stories

Use Resource 1: Preparing lessons on name or praise poems to prepare for this activity and Resource 2: Name poems and stories or Resource 3: Praise poems and stories for ideas. Choose either name poems/stories or praise poems/stories.

- Ask pupils to suggest what a name poem/story or a praise poem/story would be about.

- Ask them to listen while you read aloud the poem(s)/story(ies) you prepared.

- Ask them questions about what you have read to them.

- Ask pupils to discuss with a partner either what they know about their name or that of a family member and how they feel about this name, or what they know about the person, animal or object they wish to praise.

- Next, ask some pupils to report to the class on their discussion.

- Ask pupils to write the first draft of a poem or story about their own or family member’s name or in praise of their chosen person, animal or object.

- Collect the drafts in preparation for the Key Activity.

Did writing name or praise poems/stories give your pupils ideas for writing?

Were you pleased with the way you organised the lesson? What changes would you make next time?

With younger children, you might write a name poem together, sharing ideas and using familiar words in the classroom language.

2. Working in groups to write life stories

Some of the first stories children hear are likely to be stories about the life experiences of family or community members. The life stories (biographies) of famous people are frequently published in magazines and newspapers and even in comic form, so, whether from listening or from reading, many pupils are likely to be familiar with life stories. This is a good starting point to stimulate interest in reading and writing.

In the classroom, pupils need support from their teacher and from one another when they are learning to speak, read and write – particularly if this is in an additional language. Case Study 2 and Activity 2 show how you can give pupils opportunities to read, talk, work together in small groups and write the first drafts of the life stories of people they are interested in. Pupils need examples to guide their development as writers. The articles they read can help them organise their writing and help with sentence structure and vocabulary.

Younger pupils will need you to work with them, guiding their writing and gradually extending their vocabulary.

Case Study 2: Using pupils’ interests to develop reading and writing skills

Mr Mensah noticed that, in the playground, some Class 6 boys – who showed no interest in reading and writing during English lessons – often sat together to read the soccer newspaper, Weekend Sports. They told him they enjoyed finding out about the lives of their favourite players.

This gave Mr Mensah an idea. He asked the whole class whether they ever read newspapers or magazines and, if they did, what they enjoyed reading. Many said they tried to read stories about people who interested them, even though they couldn’t understand all the words. Mr Mensah organised a collection of newspapers and magazines for the classroom. Then he asked pupils who they were most interested in reading about. The favourites were sports stars (mainly soccer, but some basketball, athletics and boxing), musicians, film and TV stars, followed by fashion models, politicians, community leaders and successful business people.

He grouped pupils according to their interests. There were several groups for sports stars and hiplife musicians! He gave magazines and newspapers to each group and asked them to find articles/pictures about one person who interested them. Then, as a group, they helped each other to write one or two short sentences about the person’s life. They used their own words as well as vocabulary from the articles. They wrote their own title.

Mr Mensah was pleased to find that most pupils were involved in reading and, while some did more of the writing than others, everyone participated. Each group enjoyed reading their biography to another group.

Activity 2: Reading and writing life stories

Use Resource 4: Preparing lessons on life stories to prepare for this activity.

You could do the activity described in Case Study 2, and then follow it up with the one below, which is similar but more personal (for each, collect the drafts for use in the Key Activity).

- Ask pupils to read together the story you have copied on to the chalkboard or paper. Or read it to them and explain what it is.

- Discuss the features of life stories (biographies). Ask pupils to tell you what categories of people (e.g. national footballers, local musicians) they are interested in, and why.

- Give each same-interest group several newspapers and magazines that contain articles about the category that interests them.

- Ask them to find articles about a person from their chosen category and use the information to write two important facts about the person (see Resource 4 for guidance on helping your pupils to do this).

- Collect the drafts for use in the Key Activity.

If your class is very large, you could do this activity with half the class or smaller groups in turn. You could also group pupils according to their ability – mixing more able and less able to help each other. With younger pupils, you might do this as a whole-class exercise where you help by writing their ideas down and sharing their words.

3. Focus on the writing process

When we write something, it is important to make it clear what we are trying to say. We need to plan. Next, we start writing and then stop and read what we’ve written. We may decide to change the order of some words, to add or take away some information or change it around. Finally, we check for incorrect spelling, punctuation or grammar. The final piece of writing may look quite different from our first draft. We have ‘crafted’ our writing.

In the classroom, one piece of writing would be completed (i.e. crafted) before another one is begun. Case Study 3 and the Key Activity show you how to prepare for lessons in which pupils are to craft their writing.

Case Study 3: Working with a colleague to help pupils’ writing

Mrs Dorcas Andam and Mrs Beauty Tetteh teach English to Class 6 classes in Tema. They give pupils detailed feedback on their writing, so sometimes they stay after school and work together on their marking.

One afternoon, while drinking Maltina before they began marking, they agreed that they were feeling frustrated. Most pupils seemed to ignore the comments and corrections in their books. The friends thought this was strange, because they found the comments they gave each other on first drafts helped them to improve the final versions of the assignments for their professional development courses. Then Dorcas realised something important! Her pupils didn’t get a chance to do more work on the same piece of writing. Instead, there was a new topic in each writing lesson. When she said this to Beauty, her friend agreed that the same happened in her class. That’s how they’d been taught when they were at school!

They decided to try a new approach. They would use several lessons to work on drafting and crafting the same piece of writing. They would give pupils ideas to guide their writing and rewriting. At first, pupils didn’t like rewriting, but when they saw how their work improved, they started to take much more pride in it.

Key Activity: From first draft writing to crafted poems/stories

- Before the lesson, read pupils’ first drafts and decide on some general questions to ask them all to improve their work (see Resource 5: Questions for pupils). Write these on the chalkboard.

- Return the drafts, with some general comments on what you like about pupils’ writing. Explain that they are now going to craft their writing.

- Ask them to reread their first draft and to use the questions on the board to write an improved second draft.

- Ask them to exchange their second draft with a partner and give each other suggestions for improvements.

- Ask them to use these suggestions to write the final version. Go round the class and help where necessary. Encourage them to include drawings with their writing.

- If there isn’t time to complete this activity within the class period, ask pupils to complete the activity at home and report back the next day.

- Ask them how the process of drafting helped.

Were there any improvements in pupils’ writing as a result of the drafting and crafting process? How can you build on these?

With younger pupils or those less competent in the classroom language, you could work with them to draft and redraft a simple piece over two lessons – giving them space between lessons to think about what they really wanted to say.

Resource 1: Preparing lessons on name or praise poems

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Decide whether you wish to choose name or praise poems/stories to work on with your pupils.

- Choose one or more examples from Resources 2 or 3 OR from other resources that you have OR write your own poem or story.

- Write the poem(s)/story(ies) on large sheets of paper or cardboard so that when you use them in class pupils will be able to read the large print with you and then refer to the poems and stories when they are writing their own. If you don’t have large sheets of paper, write on your chalkboard.

-

Prepare some questions to ask pupils about the poem(s)/story(ies). Obviously, the kind of question will depend on what you have chosen.

For example, if you chose Tade’s or Thabo’s poem, you could begin with: ‘What do you notice about the way this poem is written?’ (Answer: Each line begins with one letter in Tade’s or Thabo’s name).

If you chose Hugh Lewin’s praise story about Jafta’s mother, you could ask: ‘Would you like to have a mother like Jafta’s? Give me a reason for your answer.’

When you have completed this preparation, you are ready to teach lessons about name and praise poems and stories. When pupils begin writing, move around the class to help anyone who finds it difficult to get started. Some may need help with ideas, others with vocabulary.

Resources 2 and 3 are all name or praise poems, songs or stories but the language is much more difficult in some than in others.

Resource 2: Name poems and stories

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

A name poem written by a teacher in South Africa

Marumo – My Praise Name by Marumo Magdalene Mafokoane

A name poem written by a teacher in South Africa

Thoughts about the letters of my name by Thabo X

A name story written by a teacher in South Africa

A naming story that was told to me by Mbhevula Ntuli

Resource 3: Praise poems and stories

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

A traditional Zulu praise poem – in isiZulu and in English translation, with some explanatory notes

| isiZulu | English |

|---|---|

| Ujama kaNdaba! | Jama son of Ndaba! |

| UJama kaluthwana kangakanani, | Jama is not deceived to the slightest extent, |

| Nasenhlamvini yomkhont’angenela, | Even on the point of a spear he can be at ease, |

| Nasemagatshen’ angaphathetela. | Even on branches he can hold tight. |

| Obengumqingo wang’itshe laseZihlalo, | He who was solid like a rock of Zihlalo, |

| Ebilingalayezwa ngabaphath’ izinhlendla, | Which could be commanded by those who carry barbed spears, |

| Thina bamaklwa singathath’ichoba sophule, | While we of the broad-bladed spears could save ourselves by using a sandstone, |

| UMabopha wakithi kwaZwangendaba, | Inspirer of our place at Zwangendaba, |

| Ongibophe zaluk’ inhlazane nemfuduluko, | Who inspired me as the cattle went out to graze at midday, |

| Obabis’ ihlaba elikuMahogo, | Who made bitter the aloe of Mahogo, |

| Othabis’ idukumbane elikuNgcingci | Who made glad the trifle of Ngcingci. |

This is a poem in praise of Jama who was an early Zulu chief. Hlaba (aloe) and Dukumbane (trifle) were the names of regiments of young soldiers who were made ‘sharp’ (bitter) or pleased (glad) by Jama.

A praise poem written by a South African pupil

Praise poem for Sekhukunene by Nathaniel Seleka

A praise song sung by children in Soweto

An explanation of some of the words and ideas follows the poem.

Ma Sisulu

Notes

- Mrs Albertina Sisulu is one of the heroes of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Her husband Walter was one of the leaders of the African National Congress and was imprisoned with Nelson Mandela on Robben Island. While Walter was in prison, Albertina was not allowed to leave Orlando township in Soweto and for much of the time she was a banned person. This meant, among other things, that she could not be quoted in the media (i.e. she was silenced – line 12). She worked in Soweto as a midwife, helping to deliver babies.

- Sawubona (line 7) is a Zulu greeting, roughly translated as ‘Hello!’

- laaitjie (line 8) is an Afrikaans word meaning ‘little child’ or ‘young one’.

- SB (line 10) refers to the Security Branch – the branch of the police who checked to see if Mrs Sisulu had defied her banning order.

A Yoruba poem in praise of the python

Some praise poetry praises animals or objects rather than people. Here is a poem from the Yoruba people. Explanation of some of the language is provided after the poem.

Python

Notes

- To walk with a swagger is to walk proudly – thinking you are the best, showing off. In Line 1, the poem describes the python as a swaggering prince.

- The questions in Lines 6 to 9 suggest that the python has many houses – both on the ground and in water.

- In verse two, the poem suggests that other animals and people would be too frightened to walk next to the snakes – that is why snakes ‘walk’ singly (by themselves).

Resource 4: Preparing lessons on life stories

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

- Collect the resources that you will need. This may take some time, but the newspapers, magazines and comics that you collect could be used for many different kinds of language lessons in addition to those on reading and writing life stories. Some pupils may be able to bring newspapers and magazines from home, so ask them to ask their families for permission to do so. Ask your colleagues and friends to contribute newspapers and magazines that they have finished with. In some countries, newspaper and magazine publishers may be prepared to donate copies to your school. Some NGOs also have excellent publications. For example, in South Africa, comics about Nelson Mandela’s life are available from the Nelson Mandela Foundation and the NGOs ‘Soul City’ and ‘Love Life’ also have useful magazine materials.

- Before you begin these lessons you must have enough reading material about a range of well-known people for each group of pupils to work with.

- Copy on to large sheets of paper or cardboard or on to your chalkboard the life story of Hugh Masekela (biography below) OR another life story of your choice that is written in fairly simple language.

- Make a list of common features of life stories to discuss with your pupils. These include:

-

- usually telling the story in a time sequence from early years to later years in the person’s life;

- highlighting the special achievements of the person’s life;

- details of something particularly interesting or amusing about the person’s life.

Now you are ready to begin the lesson!

Guiding pupils while they write life stories

While pupils are working in their groups, move round the room to check that they understand the task and are able to find articles to use. You could write a ‘checklist’ on the chalkboard to guide pupils in their writing. For example:

- name(s) of the person;

- place of birth;

- family details;

- ‘history’ – school days, first achievements, later achievements;

- interesting/sad/amusing things that have happened in the person’s life.

Encourage pupils to think about the order in which to write the information about the person and to use some of their own words. They should not just copy from the articles.

Hugh Masekela’s life story (biography)

‘The magic blower – Hugh Masekela’

Adapted from New Successful English, Learner’s Book, Grade 5 (2001), p.19 (Cape Town: Oxford University Press). ISBN: 0 19 57433 4

Resource 5: Questions for pupils – to think about how to improve (craft) what they have written in their first draft

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

- Does your poem/story have a title? If no, what would be a good title? If yes, is the title likely to interest readers? Is the title a ‘good match’ with what you’ve written about?

- Will a reader be able to follow your ideas or the sequence of events in your poem or story?

- If you have written a description, have you included plenty of details?

- Now that you’ve read your poem or story again, what would you like to add or to take out?

Section 5: Turning oral stories, poems and games into books

Key Focus Question: How can you support language learning by making and designing books?

Keywords: writing; illustrating; designing; book; cover

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used discussion to help pupils understand the similarities and differences between oral and written texts;

- developed ways pupils can turn oral stories, poems, songs or games into written and illustrated forms;

- explored how to produce books of stories, poems, games and songs for a class library.

Introduction

One important aspect of teaching is that your pupils see a real purpose to the tasks you set them. By helping pupils to make books for the class library, you will be giving them a reason for taking care with their writing and drawing. This will also encourage them to value their home languages and the classroom lingua franca or additional language. The books can be written in the pupils’ home language(s), a classroom lingua franca or an additional language. More than one language can be used in the same book. The books pupils make, with your help, will also give you extra materials for reading activities.

1. Showing that you value home languages

Pupils who speak a language at home that is different from the language of the classroom need to know that you value their home language. This is important because a home language is part of who a person is. One way of demonstrating this is to encourage your pupils to tell stories and riddles, recite poems, sing songs and explain games in their home languages and then to write these down, either in their home languages or in another language.

In Activity 1, you help pupils explore the similarities and differences between oral and written texts. You will encourage them to think about what is valuable about the oral tradition, why people write things down and which languages are used in speech and writing.

Case Study 1: Telling stories in home languages; writing them in a lingua franca:

Mr Okitikpi, a Yoruba-speaking teacher, has recently been transferred to a community in Northern Nigeria that has Hausa as a common language, but a number of pupils speak three Nigerian languages. A few parents and young adults have agreed to act as teaching ‘aides’. They know Hausa and some English and are helping Mr Okitikpi to learn Hausa so he can communicate with his pupils better. As some of his pupils can speak three Nigerian languages, Mr Okitikpi has involved these aides in storytelling activities to build pupils’ confidence in speaking and to show that their home languages are valued.

He wants pupils to write some stories down, ideally in their home languages. However, a number of the languages do not have a written form, so he decides they should write the stories in Hausa.

One of his aides discusses with pupils why people write stories down. Next, they write down their favourite story, in Hausa, so that they can put it into a book for the class library. Mr Okitikpi puts the pupils into groups for this writing activity, making sure that at least one group member is fairly fluent in Hausa and can support the others. He also asks his aide to help him monitor the writing process.

Activity 1: Writing down oral literature and games:

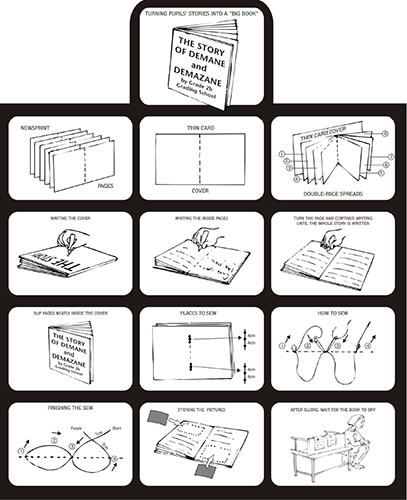

First, read Resource 1: How stories are made into books , and think about the answers to the five questions for pupils.

- Ask pupils for the titles of home language stories, poems, songs and games they know. Write these on the chalkboard.

- Discuss these questions with pupils:

- Are these home language texts written in books?

- Why do people write down stories, poems, songs and games in books?

- Would you like your home language stories, poems, songs and games to be written in books? Why, or why not?

- In which language or languages would you write poems, stories and games for a book? Why?

- How do books get written and produced? Tell pupils they will be making books for a class library.

- Ask pupils to each choose a favourite story and to write the first draft in the language of their choice.

Were you pleased with the discussion?

How did pupils respond to this activity?

2. Turning stories into books

Some kinds of learning, such as learning to play a musical instrument, use a computer or drive a car, require a great deal of practice. As a teacher, you need to give pupils opportunities to repeat and practise what they have tried before so that they can improve on their first efforts. While Activity 2 in this section is similar to the Key Activity in Section 4 , the repetition is important. Pupils will learn that writing is a process and that their written stories, poems and instructions for games will give more pleasure to others if they craft them carefully.

Writing, illustrating and reading these books may take several lessons, but as these activities provide many opportunities for language work, the time will be well spent. You can use Resource 2: A checklist for pupils to help pupils assess their work. Case Study 2 suggests how teachers can make books with pupils who are not yet very skilled as writers.

Case Study 2: Helping beginner readers and writers to make a storybook

Mrs Comfort Akpatsu teaches 60 Class 1 and 2 pupils, in a combined class, at a nomadic school in the Shai Hills. One of her colleagues teaches 48 Class 3 and 4 pupils. Both teachers regularly invite parents into school to tell stories in Ga and Dangbe to their pupils.