Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 7 March 2026, 5:06 AM

Chapter 4 Water Management in Myanmar

4.1 Introduction

This chapter brings together the issues affecting water use and water quality that have been explored in the course so far. Water is used to drive economic and social development in Myanmar, but this also leads to pollution that affects water quality and damages human health. Myanmar needs to manage its water resources more effectively to ensure continued economic and social development.

One way to do this is through the development of an integrated water management plan (IWMP) which will be explored in this chapter.

4.2 Effects of climate change on Myanmar

Climate change as a result of global warming affects Myanmar in specific and general ways. Specifically, the highly productive deltaic and low-lying coastal rice cultivation areas are exposed to sea water inundation and coastal erosion as a result of rising sea levels. Poor drainage and inadequate flood protection also lead to salt intrusion decreasing crop yields (FAO, 2011).

In the Central Dry Zone in the Ayeyarwady Basin, an increase in extreme high temperatures leads to droughts, such as the severe drought in 2009 which affected major cereal crops, and desertification. In 2010, severe drought diminished village water resources across the country and destroyed agricultural yields of peas, beans, pulses, sugar cane, tomato and rice.

Flooding is also a growing problem. The Zawgyi River flooded in October 2006 causing extensive crop damage. The heavy rains from July to October in 2011 led to flooding in the Ayeyawady and Bago Regions, Mon and Rakhine States, and resulted in the loss of approximately 1.7 million tons of rice (Government of Myanmar, n.d.). In the delta region, mangroves have been cleared for shrimp farming making the land more vulnerable to rising sea levels.

Excessive rain also heavily erodes the land with the result that there was excessive sedimentation in the water in Rakhine State in 2010, which further damaged rice seedlings and reduced harvests.

Turning from the specific to the general level, global warming in warm climates like Myanmar’s means evaporation rates will increase. This will cause soil moisture to decrease, and drying soils mean droughts will become more severe. The flipside of this is that the atmosphere has greater water holding capacity when it becomes warmer. Thus, when it rains it is likely to be more intense.

Global warming shifts weather patterns and leads to increases in the frequency of extreme events. Myanmar is the country with the highest vulnerability to climate change in Southeast Asia and is regularly threatened by natural hazards such as floods, droughts, cyclones and landslides (UN Habitat, n.d.). These natural hazards affect lives, water security for people and ecosystems.

The Myanmar Climate Change Alliance (MCCA), an organisation of government, civil society, academia and the private sector, argues that climate change will have major economic, social and environmental consequences for Myanmar. Economically, the country will suffer because it depends on rain fed agriculture. Increasing temperatures are adversely impacting agriculture leading to increasing abstraction (taking or extracting water from a natural source such as rivers, lakes, groundwater aquifers, etc.) for irrigation.

The result is a growing imbalance between supply and demand that has already led to shortages and depletion of reserves. Moreover, the scarcity of water is being accompanied by deterioration in the quality of available water due to pollution and environmental degradation.

The social implications of climate change are just as challenging. The agricultural sector provides livelihoods for almost two-thirds of the population. If crops are lost or yields reduced, farmers will suffer loss of income and hardship. Cyclones cause a loss of fishing vessels, shrimping rafts and inland fisheries for those with fisher livelihoods, leading to further economic loss and hardship. Low-income communities are disproportionately at risk from climate change because their livelihoods are less resilient to such shocks.

Environmentally, climate change is negatively impacting marine and forest ecosystems. The coastal and marine ecosystem has seen the deterioration of the mangroves, coral reefs and sea-grass beds, which are vital breeding and feeding grounds for marine life. Forests are suffering because of rising temperatures and fluctuating precipitation levels. Extreme temperatures also increase transpiration from the canopy of trees, causing increased moisture stress. This increases the vulnerability of forests to fires. Forests are an important carbon sink, but their loss releases the carbon back into the atmosphere adding to climate change.

Thus, as well as the challenges around water availability, use and pollution already explored, climate change presents a further problem that needs to be mitigated through sustainable water management. This is the ability to meet the water needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same.

Question 1

Match the impacts of climate change to whether they are mainly economic, social or environmental.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 3 items in each list.

Environmental impact

Social impact

Economic impact

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Fishing villages washed away as a result of cyclones

b.Forest fires because of extreme heat

c.Rice paddy crop destroyed by seawater inundation

- 1 = b,

- 2 = a,

- 3 = c

4.3 Managing water resources in Myanmar

The water cycle is an essential environmental service that provides a basis for many livelihoods in Myanmar. However, the increasing need for water from intensifying economic activities is putting growing pressure on existing water resources. Moreover, the water quality in Myanmar’s rivers, lakes and wetlands is impaired by intentional waste disposal, or incidentally by runoff from agriculture and other land uses.

The uneven temporal and spatial distribution of water resources creates further challenges for water allocation. The surface water and groundwater resources are not located in the areas with the most population and largest cropping intensity, creating a need for irrigation, for example, in the Ayeyarwady basin. Myanmar’s abundant water resources can help in the country’s economic development by increasing the exports of agricultural products and hydroelectricity. However, with intensifying agriculture and hydropower development, the need for sustainable water resource management becomes more acute.

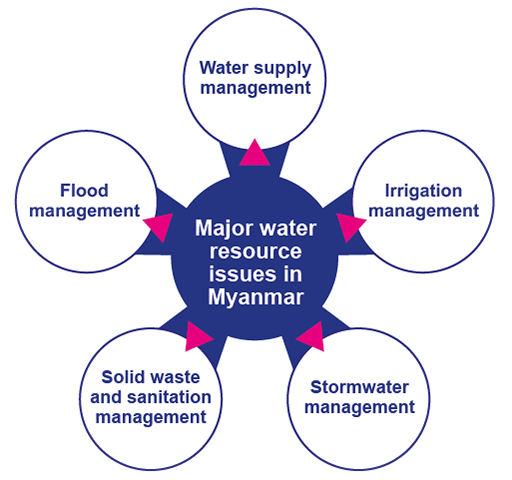

The major water resource issues in Myanmar are summarised in the diagram below.

4.3.1 Water Supply Management

Most cities and towns in Myanmar can provide water supply for domestic use but the water quality is not up to drinking water standard and there is loss through leakage and illegal tapping. The supply pipe networks, maintenance and technology are old and in need of an upgrade. Public education and participation are also important to reduce water wastage.

Most water pollution comes from improper mining, drainage from industries and the drainage systems in the cities. River conservation regulations and environmental conservation law should control water-polluting activities, but as we saw in the last chapter, water pollution control regulation needs to be robustly enforced.

4.3.2 Irrigation Management

Double crop cultivation of paddy rice and other crops has been introduced by implementing large-scale irrigation systems to increase agricultural production. The irrigation water management activities such as the construction of irrigation dams and distribution through gravity and pumping stations is helping, but more is needed (IWRM, n.d.).

4.3.3 Stormwater management

Stormwater management is the responsibility of the City Development Committees (Yangon, Nayphidaw and Mandalay) and the Department of Rural Development, which is under the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation. Urban flooding occurs in most cities after heavy rain.

4.3.4 Solid waste and sanitation management

Sanitation and waste management both refer to waste, but sanitation is primarily concerned with liquid waste and waste management is primarily concerned with solid waste. Liquid wastes are wastewater and sewage and include faeces and the contents of pit latrines and septic tanks. Solid wastes are anything in solid form that is discarded as unwanted, such as garbage, often disposed of in rivers and on unoccupied land, where it is often burnt.

Currently, about 7% of Yangon's population and 5% of Mandalay's population have access to modern sanitation facilities (IWRM, 2019). Solid waste management is also a pressing concern because of the widespread practice of open dumping of waste and limited reach of a sufficient collection service leading to surface and groundwater contamination. Building public awareness of good sanitation and waste disposal is undertaken by broadcast media such as MRTV, MWD. MRTV-4 but, without the corresponding provision of services, behavioural change is unlikely to follow.

Other waste management issues include landfills being almost at full capacity with increased potential for landfill fires, waste dumping without any compaction, methane production, and release of greenhouse gases (World Bank, 2019). Consequently, a plan is needed to manage solid waste, together with the maintenance of drainage systems and establishment of more treatment plants.

Question 2

What is the difference between liquid waste and solid waste? Match the following terms and definitions.

Two lists follow, match one item from the first with one item from the second. Each item can only be matched once. There are 2 items in each list.

Liquid waste

Solid waste

Match each of the previous list items with an item from the following list:

a.Wastewater and sewage including faeces and the contents of pit latrines and septic tanks

b.Waste such as garbage, kitchen waste, crop waste, that is discarded as unwanted

- 1 = a,

- 2 = b

4.3.5 Flood management in Myanmar

It is during the monsoon season that the country is most prone to flooding. Myanmar has an intricate river system, with vast river basins and a delta region. The rivers fill to capacity, often bursting their banks and causing flooding in the towns and villages alongside the rivers. Such riverine flooding is increasingly common as the monsoon increases in intensity. The monsoon also causes coastal flooding, as tropical storms from the Bay of Bengal generate storm surges and cause floods along the Rakhine coastline.

From time to time, there is urban and localised flooding in the cities and towns due to heavy rains, saturated soil and poor infiltration rates, together with inadequately maintained infrastructure (such as blocked drains). In the rural areas, water barriers such as dams, dykes and levees fail which destroys valuable farmlands (UN Habitat, n.d.).

Mitigation and preparedness measures are needed to limit these water management issues that can lead to loss of life, property and infrastructure. Currently, no single institution is responsible for the management of water resources, which is very sectoral: several ministries and government departments are managing water resources separately according to their own policies and mandates.

For example, there are ten water-related Ministries and three major City Development Committees (in Yangon, Mandalay and Nayphidaw), which manage water resources. There is little coordination of approaches (Aung Min, n.d.). For example, the Department of Meteorology and Hydrology is part of the Ministry of Transport and Communication, and is responsible for the water assessment of major rivers, whilst the Department of Irrigation is part of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation and is responsible for the provision of irrigation water to farmland.

Just as there are many different agencies and ministries involved in water management in Myanmar, there are also a number of applicable laws. Most of the prevailing legislation pre-dates 2000, but there have been some recent initiatives such as the Conservation of Water Resources and River Law, which was enacted in October 2006, and the Environmental Conservation Law, which was enacted in March 2012. The National Environmental Quality (Emission) Guidelines followed in 2015, setting standards for wastewater (Aung Min, n.d.).

The National Water Policy (NWP) was established in 2014. It is the first integrated water policy for the watersheds, rivers, lakes and reservoirs, groundwater aquifers and coastal and marine waters in Myanmar. It will eventually lead to a system of laws and institutions to implement the policy guided by the Myanmar Water Framework Directive (MWFD).

There is a need for more integrated, basin-wide water resources management and planning for the allocation of water resources for different water users. Data that is more reliable is required in order to have a more detailed analysis of the current status of water resources including meteorological and hydrological data, which through modelling can help forecast flooding. Data currently can be found only on an administrative area level, instead of river basin level, which prevents a good comparison of different basins for agricultural and hydropower purposes for example. This makes managing water resources at the basin level very difficult, as the catchment area is not looked at as a hydrological entity, resulting in a lack of consideration of the downstream effects of human activities.

The construction of reservoirs, levees and sluice gates, and dredging of creeks is needed, but these individual actions need to be part of an Integrated Water Policy build on accurate data. The government are moving towards an integrated water resource management law to effectively conserve and manage Myanmar’s water resources. This is happening in collaboration with the private sector, non-governmental organisations and international organisations.

4.4 What is integrated water resource management?

Water resources management enables the effective allocation of water resources across all water uses through the establishment of institutions, infrastructure, and an information system. It manages both the quantity and quality of available water together with establishing an incentives system that encourages and supports good water management. It requires collaboration between sectors and stakeholders and the proper use of scientific data to inform decision-making.

The definitive definition of Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) was outlined at the International Conference on Water and the Environment, which took place in Dublin, Ireland, in 1992, known as the Dublin Principles. They state that IWRM is a process promoting the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, so as to maximise economic and social welfare in an equitable way without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems and the environment.

Question 3

a.

Ensuring a sufficient quantity and quality of drinking water

b.

Ensuring access to a sanitation system for all

c.

Ensuring enough water for food production

d.

Ensuring enough water for energy generation

e.

Ensuring inland waterways are navigable for inland transport

f.

Sustaining healthy water eco-systems

g.

Protecting the beauty and spiritual values of lakes and rivers

h.

All of the above

The correct answer is h.

Water resource management also means managing water-related risks, such as floods, drought, cyclones and contamination. This involves a delicate trade-off between the economic goods that water resources bring for crops, inland fisheries, mining and hydropower generation for example, and protecting ecosystems and water quality.

For example, as you learned earlier, Myanmar has lost a large percentage of its forests, cut down for fuelwood as the main source of energy, and unrestricted and unplanned agricultural expansion for farmland. But forests offer natural flood protection, and without them, farmland is more prone to flooding and crop loss. Similarly, heavy irrigating of agricultural land leads to chemical run off, which pollutes drinking water and threatens human health whilst untreated industrial waste pumped into rivers and lakes threatens biodiversity and ecosystems.

Knowing what choices to make is difficult, but it is important to realise that change in one dimension of a freshwater ecosystem is likely to have impacts on other dimensions that could be unwelcome by the human population. Thus, economies and ecosystems require integrated management that accounts for the synergies and trade-offs of water's great number of uses and values.

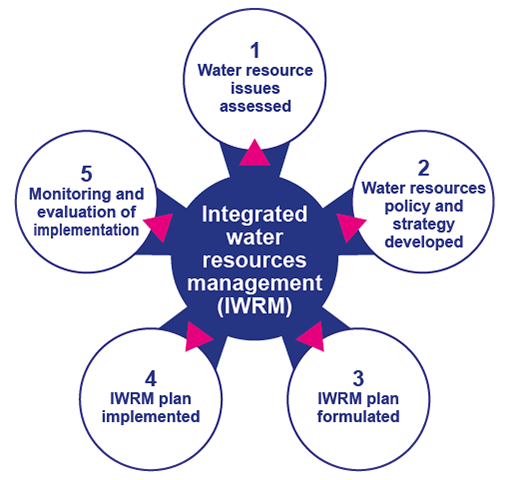

IWRM advocates an integrated cross-sectoral policy approach, enabling Myanmar to move away from the current fragmented, sector-by-sector and top–down approach, which has led to poor services and unsustainable resource use. IWRM is based on the understanding that water resources are an integral component of the ecosystem, a natural resource, and a social and economic good. Working through an inter-sectoral approach will build capacity, adaptability and resilience into the water management system for the future planning and development of Myanmar’s water resources.

There are five key steps that Myanmar needs to take to develop and implement an integrated water management plan. These are outlined in the diagram below.

The future for Myanmar rests on building the appropriate institutions and passing legislation to enable the government to regulate and coordinate water resources in an integrated way, as well as ensuring sufficient finance and human resource capacity to implement change. Moreover, these institutions and laws need to recognise the particular cultural, economic, political and power dynamics of the country.

4.5 What can you do to cut water use and wastage?

Everything we use, wear, buy, sell and eat takes water to make.

The concept of the water footprint is a way to measure the amount of water used to produce the goods and services we use. It is a versatile measure that can be applied to measuring the water used to produce a kilogram of rice or a longyi. It can be used at the individual, the organizational, the country or the global level to tell us how much water is being consumed.

Calculating water footprints heightens awareness around water usage and encourages conservation efforts. It flags the water impact on the planet in a tangible way (Water Footprint Network, 2020).

Question 4

What can you do personally to reduce the amount of water that is used?

Use the boxes below to list all the things you can think of that would cut the amount of water you use and waste. Can you fill every box?

Answer

Here are some simple measures you can personally take although not all may apply.

- Take showers rather than baths, and make your showers short

- Turn the tap off when you are cleaning your teeth.

- Boil only the water that you need when cooking or making a drink

- If you have a washing machine, save up your clothes so that you wash a full load.

- Wash dishes by filling the bowl rather than washing under a constantly running tap

- Be aware of how much water you are using when flushing a toilet

- Reduce food waste

- Water your garden in the morning or evening

- Catch rainwater

- Eat more vegetables than meat and dairy.

You might have wondered why eating more vegetables than meat and dairy is a water conserving measure. Rearing animals for meat and dairy is much more water intensive than growing vegetables and other foods as can be seen in Figure 5. By cutting down on meat and dairy and eating vegetables and other foods you will be helping to conserve water.

| Product | Water required/litres |

| fresh meat – beef | 15000 |

| fresh meat – lamb | 10000 |

| poultry meat | 6000 |

| palm oil | 2000 |

| cereals | 1500 |

| citrus fruit | 1000 |

| pulses, roots and tubers | 1000 |

Thus, the water footprint looks at both direct water consumption in terms of what an individual uses (drinking, cleaning teeth, washing the dishes) and indirect water use in terms of goods and services that the individual consumes that are produced using water (clothes worn, food consumed, and products enjoyed).

Your personal water footprint

Find out your personal water footprint by inputting your water usage information. This should take you no more than a couple of minutes.

You should have a water footprint that is measured in cubic meters (m³) per year. Were you surprised at how much or how little water you use?

You can also undertake a more detailed evaluation of your water footprint.

This will give you a clearer steer on how to reduce your water footprint.

4.6 Next steps

If after studying this course and its story of Myanmar’s abundant water resources and their management you are excited to learn more, and do more, there are a number of things you could do. Three next steps are set out here.

Newsletter

You could sign up for a newsletter from an organisation that does research on ecology and water resource management. Some examples are:

Asian Ecology Section (AES) of the Ecological Society of America

Volunteer

You could volunteer at an environment group. Volunteering enables you to become more informed but also to work for the changes you value. Some examples are:

Career

You might want to pursue a career in ecology or more specifically water management. Of course, this route will entail much more studying and training. There are many water related career options.

For example, if it is the water cycle that inspires you, and the interface between the land–surface–water–atmosphere interests you, you could become a hydrologist.

If you are passionate about the seas and oceans, then you might consider a career in oceanography.

If you are fascinated by the changing weather conditions and making predictions based on models, then you might consider a role as a meteorologist.

If you are intrigued by the design and building of major waterworks such as dams and irrigations systems, then a future as a water engineer might appeal.

4.6 Conclusion

In this final chapter, you have learned about:

- Myanmar’s vulnerability to climate change

- The particular water management issues that the country faces

- How the current approach to water management is fragmented, sectoral and top–down.

One answer to the resultant level of poor services and unsustainable resource use is IWRM. Working through an inter-sectoral approach will build capacity, adaptability and resilience into the water management system for the future planning and development of Myanmar’s water resources.

You have also reflected on what you could as an individual do to conserve water and you have calculated your own water footprint.

Statement of Participation

There is a Statement of Participation awarded for studying this course. To gain this you must have completed all four chapters of the course and attempted all the questions. You can still do this now.

References

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Important: *** against any of the acknowledgements below means that the wording has been dictated by the rights holder/publisher and cannot be changed.

279885: Module Image: Jon Gregson

280656: Introduction Image: With kind permission of Yin Tun

279053: Chapter 1: Myanmar map: Figure 1: © Peter Hermes Furian / 123 Royalty Free

277978: Chapter 1: Glacier: Figure 2: Susan Fawssett

277988: Chapter 1: Unsaturated and saturated areas in an aquifer: Figure 3: Emma Fawssett

279153: Chapter 1: The hydrological cycle or water cycle: Figure 4: Houghton, J. (2004) Global Warming (3rd edn), Cambridge University Press

277996: Chapter 1: Government of Myanmar 2014: Figure 5: Myanmar Integrated Water Resources Management Strategic Study (2014) Executive Report

279166: Chapter 1: Weather Atlas: Figure 7: Taken from https://www.weather-atlas.com/

277990: Chapter 1: Myanmar’s rivers: Figure 8: Jon Gregson

277992: Chapter 1: Government of Myanmar 2012: Figure 9: Myanmar’s National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) to Climate Change (2012). Found here: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/napa/mmr01.pdf

123456: Chapter 2 - still to be uploaded: Figure 1: Jon Gregson

280820: Chapter 2: Global water demand by sector to 2040: Figure 2: UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme (2019) The United Nations world water development report 2019: leaving no one behind. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike Licence http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

279435: Chapter 2: Map of Asia: Figure 3: © ii-graphics / iStock / Getty Images Plus

277998: Chapter 2: Irrigation of agriculture 1: Figure 6: Withheld

277999: Chapter 2: Moat around Mandalay: Figure 8: Withheld

279357: Chapter 2: The major rivers in Myanmar: Figure 10: © Rainer Lesniewski / 123 Royalty Free

278002: Chapter 2: Mining in Hpa-An Myanmar: Figure 11: Withheld

123456: Chapter 3 - still to be uploaded: Figure 1: Withheld

278017: Chapter 3: Rubbish dumped by a river: Figure 3: Jon Gregson

278019: Chapter 3: Oil spill: Figure 4: Jon Gregson

278020: Chapter 3: The water quality of Myanmar’s rivers creeks and streams is declining: Figure 5: Withheld

123456: Chapter 4 - still to be uploaded: Figure 1: Jon Gregson

278022: Chapter 4: Low-income communities are most at risk from climate change such as rising sea levels: Figure 2: Withheld

278023: Chapter 4: Flooding in Yangon: Figure 4: Withheld

278024: Chapter 4: Solid waste: Figure 5: Susan Fawssett