Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Thursday, 5 March 2026, 4:15 PM

Module 3: Community issues and citizenship

Section 1 : Exploring good citizenship

Key Focus Question: How can you use different ways of organising pupils to develop their understanding of citizenship?

Keywords: classroom organisation; large classes; assessing learning; thinking skills; citizenship; rights; responsibilities

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- developed your skills to help you relate pupils’ previous knowledge to new knowledge about citizenship;

- found different ways to help pupils find out about community responsibilities;

- organised a school assembly.

Introduction

Large classes present special problems for teachers – particularly if they are multigrade classes (see Key Resource: Working with large classes and Key Resource: Working with multigrade classes). In this section, we make suggestions about using different types of classroom management for developing pupils’ understanding of citizenship.

Just telling pupils about their roles and responsibilities as citizens has much less impact than involving them in active experiences. This section helps you think about different ways to find out what they know and use this to extend their understanding.

1. Using pairs and groups to discuss rights and duties

All citizens, including children, have rights and duties (responsibilities), but these vary from person to person. In order for pupils to understand this, they need to explore what rights and responsibilities mean for them, share their findings with other pupils and consider the differences. To do this, they need to talk either as a whole class or in pairs or groups.

Citizenship is a difficult idea for young pupils and they may not understand it at first. It is a good idea, therefore, to relate it to something they know – such as the kinds of tasks that are carried out at home. With older pupils, you will be able to explore the topic more deeply and extend their understanding by thinking about their roles and responsibilities within the wider community.

Case Study 1: Using desk groups to discuss family rights and duties

Mrs Nqwinda is a teacher in MalbenaPrimary School in Mndantsane in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. She has a Grade 4 class of 62 pupils who sit in groups of five around each desk. It is not easy to move the children or the desks, so she used desk groups to discuss the duties pupils have to carry out at home. She chooses the group work method because she wants to make sure that all the pupils have a chance to share their ideas.

As they discuss their duties for ten minutes, she moves around the classroom making sure that no one is dominating the discussion and reminding each group to think about the three duties they are to feed back on.

The pupils find this an easy task. As the groups feed back their answers, Mrs Nqwinda writes each new duty on the chalkboard. She is interested to find that most of the girls help their mothers with tasks around the house, like cleaning and cooking and looking after smaller children. Most of the boys help their fathers and uncles with fetching wood and water, and some of them work in the fields and gardens. They have an interesting talk about gender roles in the household.

Mrs Nqwinda then asks if they could say what things they were free to do in their family. The pupils find this task more difficult, so she encourages them to discuss in their groups before giving feedback. Mrs Nqwinda writes their answers on the chalkboard and explains that these things they are free to do are their ‘rights’. She checks they understand the difference between duties and rights.

See Resource 1: Rights and duties of children for the list of her pupils’ rights and duties in the home.

Activity 1: Pair work to discuss rights and duties in the family

- Discuss the word ‘duties’ with your class and make sure they understand what it means.

- Ask the pupils, in pairs, to discuss and list the duties they have to carry out at home.

- After ten minutes, ask each pair in turn to give a different duty and list these on the chalkboard (many will have the same duties). Make sure they all understand these are their duties. Ask each pupil to record their own list of duties in their book.

- Next, ask the pairs to discuss the things they are free to do in their homes (such as read books, go to worship, go to school, play inside or outside).

- List their ideas on the chalkboard and explore their understanding about how these are their ‘rights’.

- Ask them to list and draw the things they like doing most – duties or rights.

Did you find working in pairs easy to manage? If so, why? If not, why?

How would you change this activity to improve it next time?

Did the pupils’ knowledge and ideas surprise you?

2. Rights and duties and the community

We all live in a group or family, and our family is part of a group, such as a village or a community. Within our community we have rights and duties. This means we must do certain things in the community and the community must do, or provide, certain things for us. Resource 2: Rights of the child will help you prepare for this topic.

Pupils need to be able to meet expert people who are willing to talk with them about their ideas on this topic. This will help pupils to understand their responsibilities in the community and motivate them to learn. Before a visitor comes to your classroom, you may need to think about moving the furniture to make the atmosphere more welcoming. This will make the visitor feel comfortable and help the pupils’ learning because they can see and hear better. See Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource for further information.

Case Study 2: Organising the classroom to discuss community responsibilities

Mr Mabikke wanted his 48 Primary 4 pupils to discuss their community responsibilities. He decided that the layout of the classroom was not helpful for group discussion work so he made a plan for a new organisation of the desks. He discussed it with his head teacher, who approved the change. With a fellow teacher to help him, he reorganised the classroom into eight groups, each with three desks arranged to seat six pupils. The next day, the children were excited that the classroom was different. Mr Mabikke explained that the arrangement would mean they could do more group discussion.

He asked the pupils to discuss, in their groups, what the community provides for them – the rights of the people living in the community. But first he talked with them about taking turns to speak in their groups and listening to each other with respect. Each group was to make a poster showing the different things the community provides as their rights as members of the community.

His pupils knew that they also had duties along with rights so, in their groups, they discussed what their duties in the community were and then they marked these on their poster in a different colour and provided a key.

All the posters were displayed on the wall so the groups could see everyone’s ideas before they had a final discussion about which were most important rights and duties.

Activity 2: Using local experts to motivate pupils

- Discuss with your pupils their duties in the community.

- Guide their talk towards care for the environment, respecting people and property, taking care of each other. Organise the class into groups and ask the groups to make a poster, write a poem or a story, or draw a picture to show their ideas.

- Discuss their rights in the community – help them understand they have a right to education, to medical care, to be safe in the streets and their homes, and to speak their opinions.

- Talk about community leaders and other important people in your community. Make a list of all the people who serve the community.

- Decide who they would like to visit the school to tell them about their work in the community. It could be a village elder, a community leader, a political leader, a nurse, a librarian, a police officer or a religious leader.

- See Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource for guidance. Arrange the visit and prepare questions with your class to ask the visitor.

- After the visit, discuss with the pupils what they found out about the work of the visitor.

3. Planning an assembly on citizenship

To qualify as a citizen of any country you have to meet certain criteria. These are usually laid down in the Constitution. Try to get a copy of the Constitution of your country and see what it says. Resource 3: Excerpt from the Constitution lists criteria for qualification as a citizen.

One way to explore your pupils’ ideas on citizenship is given in Case Study 3.

School assemblies can bring a topic to a close in a way that will motivate your pupils. How to prepare for a school assembly is explored in the Key Activity.

Case Study 3: A visit from the local government chairman to discuss citizenship

Mrs Makoha, from a small rural school in Uganda, invited the Regional District Commissioner (RDC) to visit her Primary 5 class of 56 pupils. The RDC brought with him a photograph of the president, the national flag, coat of arms/national emblem, his identity card and passport. He explained to the children about the importance of these things in being a Ugandan. He explained what the different parts of the flag symbolise. They also sang the national anthem and made a list of all the events where they sing the national anthem.

After the visit, Mrs Makoha organised the class in small groups around their desks and asked them to discuss why it is important for them to be a citizen of Uganda. She moved around the class and guided the groups to stay focused on the task and to listen to each other’s ideas.

Next, she asked them to work individually and write their own reasons in their books. She collected in their work and was able to assess how much each pupil had learned about citizenship. There were five pupils whose reasons were less well developed and Mrs Makoha discussed the reasons with these pupils during break to assess whether they understood the ideas.

Key Activity: Presenting learning in a school assembly

Ask your head teacher if you can hold a school assembly on ‘Being a good citizen’.

Discuss what the content of the assembly might be with your class.

Each group prepares their part and the resources needed. You might want to suggest to your pupils that the following need to be included:

- Who is a citizen?

- Rights and duties in the home.

- Rights and duties in the community.

- Symbols of national identity – flag, anthem, identity card, coat of arms, passport.

- Why is it important to be a good citizen?

Give groups different tasks and allow them time to prepare their contributions – maybe over several lessons.

Make the task clear, so that each pupil produces a piece of work that you can use to assess their learning.

Encourage them to write poems or texts for reading, paint flags or find a text they want to read or use.

Agree the order for the presentations and rehearse.

Present your assembly to the school.

Afterwards, discuss with the pupils what worked well and what could have been improved. How well did they think the rest of the school understood about citizenship?

Resource 1: Rights and duties of children – Mrs Nqwinda’s class list

![]() Example of pupils' work

Example of pupils' work

| Our duties are: | Our rights are: |

| Cleaning the house | Somewhere to live – shelter |

| Fetching wood/water | Food to eat |

| Looking after younger children | Protection from harm |

| Cooking | Care from adults |

| Working on the land | Medical care when sick |

Resource 2: Rights of the child in Uganda

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Rights of the Child in Uganda

In line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child passed in 1990, the Ugandan Government passed a law in 1995 known as the Children’s Statute. The Rights of the Child are as follows:

A child in Uganda:

- Should have the same rights as an adult, irrespective of sex, religion, custom, rural or urban background, nationality, tribe, race, marital status of parents or opinion.

- The right to grow up in a peaceful, caring and secure environment, and to have the basic necessities of life, including food, health care, clothing and shelter.

- The right to a name and a nationality.

- The right to know who his or her parents are and to enjoy family life with them and/or their extended family. Where a child has no family or is unable to live with them, he or she should have the right to be given the best substitute care available.

- The right to have his or her best interests given priority in any decisions made concerning the child.

- The right to express an opinion and to be listened to, and, to be consulted in accordance with his or her understanding in decisions which affect his or her wellbeing.

- The right to have his or her health protected through immunisation and appropriate health care, and to be taught how to defend himself/herself against illness. When ill, a child should have a right to receive proper medical care.

- A child with disability should have the right to be treated with the same dignity as other children and to be given special care, education and training where necessary so as to develop his or her potential and self-reliance.

- The right to refuse to be subjected to harmful initiation rites and other harmful social and customary practices, and to be protected from those customary practices which are prejudicial to a child’s health.

- The right to be treated fairly and humanely within the legal system.

- The right to be protected from all forms of abuse and exploitation.

- The right to basic education.

- The right to leisure which is not morally harmful, to play and to participate in sports and positive cultural and artistic activities.

- The right not to be employed or engaged in activities that harm his or her health, education, mental, physical or moral development.

- A child, if a victim of armed conflict, a refugee, or in a situation of danger or extreme vulnerability, should have the right to be among the first to receive help and protection.

Resource 3: Excerpt from the constitution of Uganda, showing those who qualify to be a Ugandan citizen

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Citizens of Uganda

9. Every person who, on the commencement of this Constitution is a citizen of Uganda shall continue to be such a citizen.

Citizenship by birth

10. The following persons shall be citizens of Uganda by birth:

(a) every person born in Uganda one of whose parents or grandparents is or was a member of any of the indigenous communities existing and residing within the borders of Uganda as at the first day of February 1926 and set out in the Third Schedule to this Constitution; and

(b) every person born in or outside Uganda one of whose parents or grandparents was at the time of birth of that person a citizen of Uganda by birth.

Foundlings and adopted children

11. (1) A child of not more than five years of age found in Uganda, whose parents are not known, shall be presumed to be a citizen of Uganda by birth.

(2) A child under the age of 18 years neither of whose parents is a citizen of Uganda, who is adopted by a citizen of Uganda shall, on application, be registered as a citizen of Uganda.

Citizenship by registration

12. (1) Every person born in Uganda:

(a) at the time of whose birth:

(i) neither of his or her parents and none of his or her grandparents had diplomatic status in Uganda; and

(ii) neither of his or her parents and none of his or her grandparents was a refugee in Uganda; and

(b) who has lived continuously in Uganda since the ninth day of October 1962 shall, on application, be entitled to be registered as a citizen of Uganda.

(2) The following persons shall, upon application be registered as citizens of Uganda:

(a) every person married to a Uganda citizen upon proof of a legal and subsisting marriage of three years or such other period prescribed by Parliament;

(b) every person who has legally and voluntarily migrated to and has been living in Uganda for at least ten years or such other period prescribed by Parliament;

(c) every person who, on the commencement of this Constitution, has lived in Uganda for at least 20 years.

(3) Paragraph (a) of clause (2) of this article applies also to a person who was married to a citizen of Uganda who, but for his or her death, would have continued to be a citizen of Uganda under this Constitution.

(4) Where a person has been registered as a citizen of Uganda under paragraph (a) of clause (2) of this article and the marriage by virtue of which that person was registered is:

(a) annulled or otherwise declared void by a court or tribunal of competent jurisdiction; or

(b) dissolved,

that person shall, unless he or she renounces that citizenship, continue to be a citizen of Uganda.

Citizenship by naturalisation

13. Parliament shall by law provide for the acquisition and loss of citizenship by naturalisation.

Section 2 : Ways to investigate gender issues

Key Focus Question: How can you use interactive strategies to discuss gender issues?

Keywords: gender; role play; stereotyping; single-sex groups; questionnaire; local experts

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- explored attitudes to gender through single-sex group work;

- used reverse role play to highlight gender stereotyping;

- used local experts and drama presentations to share ideas on gender issues.

Introduction

There are certain behaviours in society that are often seen to be appropriate for either boys or girls, not for everyone. Some of these behaviours may negatively affect girls’ and boys’ self-esteem and aspirations, and not serve them well when it comes to learning in the classroom. Researchers note that girls are often shy of speaking up in class and sometimes fail to give answers even when they know them.

The activities in this section will help you to explore gender stereotyping with your class and to see gender roles, both male and female, in more positive ways.

Resource 1: Gender issues provides background to some of the issues about gender.

1. Using group work to explore gender differences

Gender stereotyping, although a wider social issue, starts in the home. Without realising it, many adults treat the boys and the girls in their family in different ways – it has always been like that and they see no reason to change.

Such consistent behaviour then causes girls, in particular, to believe that this ‘is just the way things are’ and there is nothing they can do about it. Boys also accept the situation because it tends to benefit them.

You can explore these differences with your pupils by working in single-sex groups to help your pupils talk about their own behaviour and beliefs.

In an earlier case study (Module 2, Section 2, Case Study 2), one teacher asked her pupils to bring family rules to class. At the time, the class saw that there were different rules for boys and girls. She decided to plan some lessons on gender, later in the term. Case Study 1 shows what happened in one of these lessons.

Case Study 1: Using drama to explore gender issues

The teacher found the list of family rules from a previous lesson. She thought about how to explore the issues around the different treatment of boys and girls in the family and decided that drama would be a good method. See Key Resource: Using role play/dialogue/drama in the classroom for ideas.

She organised the class into ‘family’ groups of different sizes, with pupils playing different family members. One group was only four people, one group was 11. She asked the groups to make up a play about a family to show how boys and girls are treated. She gave them the whole lesson to do this and went around each group to help and support them. She asked questions like ‘So what would happen next?’ ‘How could you…?’

She asked them to bring in some items to help identify different people in the family and to rehearse their plays during break times.

Over the next few lessons, each group in turn performed their play and afterwards the whole class discussed what they had seen. After watching all the plays and discussing them, they realised that girls had less freedom to choose than boys. They had a vote to decide whether this was fair, and the class agreed that boys and girls should be given equal opportunities and not be denied access to activities and work because of their gender.

Activity 1: Single-sex group work

To help your pupils explore and explain their feelings concerning gender roles, this activity uses single-sex groups.

Hand out the questionnaire in Resource 2: Gender – what do you think? to each pupil and explain the rules to the whole class.

Give them ten minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Each pupil shows their answers to their neighbour and they discuss.

Organise the class into single-sex groups of between five and seven pupils.

Each group prepares a list of all the different activities they do:

- on schooldays;

- at weekends;

- during holidays.

Groups present their list of activities – which you write on the board – making a list for girls and one for boys.

Discuss the lists with the class. Ask about fairness. Ask why they think the activities are different.

Ask the pupils to write an essay called ‘How and why are girls and boys different from each other?’ Ask them to include their own views. Younger children can draw pictures of activities they do and compare them with each other.

2. Using role play to explore gender differences

Role playing can be a very powerful teaching and learning method – especially when dealing with sensitive topics in life skills or citizenship lessons. It is particularly useful when exploring issues of gender with your pupils. It can help pupils to speak more freely because they are talking about the behaviour of other people rather than their own behaviour. (See Key Resource: Using role play/dialogue/drama in the classroom.)

It is important to explore where gender stereotypes come from. Pupils need to recognise when stereotypical behaviour is reinforced. Much of this happens in the family, but you may want to look at your own behaviour. Do you reinforce gender stereotypes in your classroom? Were gender stereotypes reinforced in your own family? Case Study 2 shows how one teacher used his own experience to explore gender with his class.

Case Study 2: Using childhood experience to discuss gender

Mr Daasa wanted to work with his class on gender issues. He spent some time thinking about what to do. He remembered that when he was a child, his father used to tell him to ‘act like a man’. He also remembered that his two sisters were often told off for not ‘being ladylike’. He decided to use these examples to introduce his lesson.

He prepared two sheets with the following titles: ‘Act like a man’ and ‘Be ladylike’. He asked the boys to say what it means to act like a man. When the boys ran out of ideas, he asked the girls. He did the same for the girls, asking what words or expectations they had of someone who is ladylike. He wrote all their ideas on the sheets.

He drew boxes around certain words on the lists and explained that behaving in this way can stop pupils wanting to succeed. They talked about how it is alright for boys to like machines and sport and for girls to like cooking and looking after children, but the problem comes when we feel we must fulfil these roles ‘to fit in’. Some girls may wish to work with machines etc. and some boys may want to look after children or be cooks, but they don’t say so because they might be laughed at.

In small groups, the pupils discussed when they had felt under pressure to act in certain ways and did not want to. They discussed what they could do to be accepted as they were and perhaps do things differently to their parents or carers.

Activity 2: Reverse role play

In this activity, we want you to prepare some role plays where the ‘normal’ roles are reversed (see Resource 3: Reverse role play for an example). This may help you to think about different situations where you can swap the traditional roles played by men and women. Read Key Resource: Using role play/dialogue/drama in the classroom.

Explain to your class about the activities and their purpose and about not laughing at people, but to think about the issues raised as they watch.

After each role play, ask pupils to discuss, in mixed-gender groups, the following questions:

- What do you think about this situation?

- How did you feel when you were watching the role play, and why?

- What do our feelings show about how we see the roles of men and women in society?

- If the role play were the other way around, would you have felt differently?

If you have younger pupils, you will need to make your role plays quite simple. Also, you may feel you need to guide their discussion afterwards, rather than asking them to discuss the questions in groups.

3. Raising awareness of gender issues

There are many forms of abusive behaviour and it is girls and women who are more often the victims. This does not mean that boys cannot also be abused; just that girls and women have tended to have had a more passive role in society, while males have been more dominant.

If you are going to explore this area with your class, you will need to prepare very carefully and be able to support your pupils as some ideas may be very uncomfortable and challenging for them. You may also find that you uncover some incidences of abuse, and you must be prepared to support your pupils, sensitively and discreetly. Resource 4: Gender violence is an extract from a research paper discussing some of these issues in Ghana, which you could read to give you background knowledge.

You may not feel equipped to deal with this sensitive subject alone – so you could follow the lead of Mrs Yarboi in Case Study 3, who asked someone from a local NGO to come and assist with her class discussion on abuse.

Case Study 3: Using a local expert to help discuss sensitive issues

Mrs Yarboi’s Primary 5 class had been working for some weeks on gender stereotypes and how they can negatively affect girls’ progress in the classroom and in life. It had been a difficult time for Mrs Yarboi because the boys felt that they liked the status quo and did not see that it needed to be changed.

She decided to get in some expert help and contacted a local NGO who were working in rural development projects in their town. She had met a lady called Amina who was their gender specialist.

Amina came to the school and talked to the class about abuse. They identified that abuse can be mental as well as physical and sexual. Amina told the class of some stories of young people who had been abused by their parents, by other family members and even by people from their religious group. She also talked of ways in which these pupils had been helped and what organisations there are to help people. It made some of the pupils very upset that people can behave that way.

During the talk, Mrs Yarboi noticed that two girls started crying. After the visit from Amina, Mrs Yarboi asked the two girls if they would like to go and talk to Amina and she made appointments for them.

In the next lesson, Mrs Yarboi asked her pupils to write about abuse and explain their feelings about it. From this, she was able to see how much each pupil had understood and was able to see how they had reacted to the stories Amina told.

Key Activity: Organising a school event about gender issues

Having explored some issues about gender with your class, suggest to them that they share what they have found out with the rest of the school.

Ask them how they could do this. Could they:

- produce a play?

- do an assembly?

- write an information book?

- write a poem?

You could do more than one if you have a large class. Pupils could choose which group they join.

Once they have decided what they want to do, ask them to plan what to say and the best way to say it. Remind them to be sensitive to their audience and careful how they present their ideas.

Give them time to draft or practise what they are doing. When ready, allow them to present their play, book, poem or assembly to the class for constructive feedback, so that they can make any changes before they do the real performance or presentation to the school.

After the event, allow your pupils the opportunity to assess the impact of their actions.

Think how you can support your pupils and build on this task.

Resource 1: Gender issues

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

- Gender describes those characteristics of men and women that are socially determined rather than biologically determined.

- Many of the pupils’ reactions come from the way they have been socialised, which leads to an unconscious gender stereotyping.

- In the family, men are generally considered the heads, and decision-making is largely dominated by them.

- There are gender disparities in access to education, economic opportunities and health care.

- There is bias in favour of education for boys, coupled with issues of early pregnancy resulting in the high drop-out rate of girls from school.

- There are imbalances in employment by sector and sex. Within the agriculture sector, women are the major food producers.

- People are born male or female, but learn to be girls or boys who grow into women or men.

- People are taught what the appropriate behaviour and attitudes, roles and activities are for them, and how they should relate to other people. This learned behaviour is what makes up gender identity and determines gender roles.

Issues in gender teaching

- Gender issues are sensitive and therefore rules should be strictly observed in order to ensure that discussion does not become just a fight between the girls and the boys.

- You need to help both sexes appreciate the dilemmas and choices of the opposite sex.

- It is important for pupils to understand how gender stereotypes are reinforced by behaviour in the family, in the school and in society.

- You need to help your pupils develop strategies and skills to challenge unfair gender situations.

Resource 2: Gender – what do you think?

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

Read each statement and draw a ring around the score to show how much you agree or disagree with the statement.

- 5 means you fully agree.

- 1 means that you completely disagree.

- If you really do not know, you can circle 3.

| a | Boys are stronger than girls | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| b | Cooking is a girl’s job | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| c | Girls don’t have time to study because of their chores | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| d | Girls wake up before boys | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| e | At school, girls do more work than boys | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| f | Boys are more intelligent than girls | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| g | Education is more important for boys as they must support a family when they are older | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Resource 3: Reverse role play

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Mrs Seidu is late

Mr Seidu is busy cleaning the house. He is carrying the baby on his back because she will not stop crying. Annie, the five-year-old, is pulling at his legs because she wants something. Mr Seidu is obviously tired, but dinner is cooking on the small fire. He shouts at some older children outside to go and fetch more wood for the fire. He talks about his problems as he works. He is worried that there may not be enough food when his wife comes home from work at the council.

Mrs Seidu arrives home. She is a little drunk and she is angry that the dinner is not ready and the house is not clean. She shouts at Mr Seidu and they have an argument, then Mrs Seidu hits Mr Seidu and storms out of the house saying she is going to get her dinner somewhere else.

Resource 4: Gender violence

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Studies from around the world show that gender violence is a major feature of school life for many adolescent pupils, especially girls. For girls in Sub-Saharan Africa, particular aspects of this violence include sexual abuse and harassment by older male pupils and male teachers, and, in the vicinity of the school, by ‘sugar daddies’ who seek sex in exchange for money or gifts. Boys as well as girls are exposed to regular verbal abuse and insults from both teachers and other pupils, and excessive corporal punishment from both male and female teachers. Boys too may be victims of sexual abuse.

Violent schools are breeding grounds for potentially damaging gendered practices, which remain with the pupils into adult life. Some may themselves become abusers. When school authorities fail to clamp down on gender violence, they send the message to pupils that it is a ‘normal’ feature of life. Failure by those in authority to investigate allegations and report offenders, lack of prosecution of teachers and others guilty of sexual misconduct, and lack of information for parents and pupils about their rights and available channels for complaints, allow such behaviour to continue unchecked.

Gender violence is a sensitive area to research because it involves sexual abuse, which is a taboo topic, one that we would prefer to ignore. Abuse of schoolchildren remains largely hidden because victims are reluctant to talk about their experiences to teachers and parents, and those in authority may find easy excuses for a lack of action. In Ghana, as elsewhere, people prefer to talk about abuse as being something experienced by others.

Girls are particularly at risk of violence and abuse because:

- women and girls occupy a subordinate status in society and are expected to be obedient and submissive – this makes it difficult for them to resist or complain;

- boys learn that masculine behaviour involves being aggressive towards females;

- girls who make allegations of sexual abuse by teachers and other men are often not believed;

- teachers often fail to take action against boys who use aggressive and intimidating behaviour towards girls;

- girls have fewer opportunities to earn casual income than boys, so poverty pushes some girls into having sex as a means of paying school fees or meeting living expenses. Engaging in transactional sex or sex with multiple partners increases the risk of HIV and AIDS.

Gender violence includes:

- sexual harassment and abuse;

- bullying, intimidation and threats;

- verbal abuse, taunts and insults;

- physical violence and assault, including corporal punishment and other physical punishments;

- emotional abuse (e.g. tempting someone into a sexual relationship under false pretences such as promises of marriage);

- psychological abuse (e.g. threatening to beat up a pupil or fail them in an exam).

The government of Ghana has made a concerted effort to increase enrolments at primary and JSS levels, especially among girls. The establishment of a Girls’ Education Unit in the Ghana Education Service and the appointment of Girls’ Education Officers at the regional and district levels to oversee improvements in girls’ participation are significant developments. Despite these efforts, girls continue to be enrolled in fewer numbers than boys, and to have higher dropout rates and lower achievement. It may be that abusive and intimidating behaviour in schools undermines efforts to improve girls’ participation.

There is an urgent need for a more coordinated, proactive and system-wide response to combat the problem of school-based abuse. The study revealed weaknesses in terms of linkages between the district education office and the national level response to violence and abuse in the school environment. A holistic approach is required, working with all categories of stakeholders, e.g. teachers, parents, pupils, government officials in education, health and social welfare, the police, child protection agencies and NGOs working with woman and children. The example of one head teacher’s misconduct is informative, as it shows how difficult it still is for communities to gain redress, despite efforts to delegate powers of educational decision-making to regional and local bodies and to give political voice to the people through district assemblies and bodies such as school management committees.

Schools should:

- develop specialised curriculum inputs on abuse within a human rights framework, and provide gender-based training courses, workshops and materials for all teachers;

- provide pupils with gender awareness training to eliminate negative perceptions about girls and make boys aware of the negative impact of aggressive behaviour, e.g. through clubs;

- ensure that pupils receive information on child abuse, children’s rights and protection through the life skills curriculum and other materials; ensure that they know how to report cases of abusive actions, whether to parents, teachers or adult relatives;

- teach life skills and Geography and Citizenship through methods that engage pupils in discussion and reflection on their own experiences. Skilled facilitators are needed;

- engage peer educators to visit schools to talk about sexual violence and other issues that concern pupils.

Head teachers and teachers

School head teachers are crucial in ensuring that pupils learn in a supportive environment. Less authoritarian schools are not necessarily ones with poor discipline. Strong leadership is key.

Studies show that schools with high attendance and achievement are those where expectations of both teacher and pupil behaviour are high, where the school culture is supportive of both (and includes teacher professional development) and where regulations are enforced fairly and firmly.

School head teachers can work with teachers to:

- create a pupil-friendly environment that is conducive for learning, by working with pupils, especially girls, supporting their personal development and protecting their rights;

- attach importance to gender equity in a whole-school approach;

- take effective action against cases of abuse and bullying in the school, confront the issues and deal with them as serious disciplinary matters;

- consider setting up a Student Council with pupil representation and involvement in decision-making;

- foster more trusting relationships between pupils and teachers. The research shows that pupils distrust their teachers and rarely confide in them;

- strengthen G&C teaching so that it engages pupils with the issues and develops understanding. A traditional didactic approach is not suitable. Allow space for reflection, analysis and open discussion of taboo topics. Life skills should promote consent, negotiation and consultation in adolescent relationships rather than power domination and control.

Parents

Parents and carers should be encouraged to:

- listen to what children tell them and refrain from blaming girls when they make allegations;

- provide their children, especially girls, with basic school items;

- refrain from using abusive language towards children;

- show interest in their children’s progress in school, monitor their attendance and discuss their education with teachers;

- refrain from entering into negotiations for compensation with teachers who have made their daughters pregnant.

Adapted from: Gender Violence in Schools: Ghana 3 Newsletter March 2004

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Text

Resource 4: Gender violence: Adapted from: Gender Violence in Schools: Ghana 3 Newsletter March 2004

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Section 3 : Looking at work and employment

Key Focus Question: How can different ways of grouping pupils develop understanding of work and employment?

Keywords: group work; collaboration; debate; local contexts; work; employment

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used ‘think-pair-share’ to help your pupils realise the importance of work in the home and community;

- prepared collaborative (joint) activities and assessed individual learning;

- used local contexts and resources to motivate pupils to understand about work and employment.

Introduction

The way you group pupils for discussion can make a big difference to their learning experience. Sometimes you will want to group them according to ability; sometimes you will want to mix quicker and slower pupils. If you have a large and/or multigrade class, you may need to group them according to age or grade. In this section, you will use different forms of grouping for both individual and collaborative working to help pupils discuss and reflect on their understanding of work and employment.

You can also use local contexts and resources to motivate pupils so that they use their own initiative to make useful and saleable items from local materials.

1. Using group work and pair work to explore employment

Young people and adults do different activities as work and employment. In this section, we suggest you use a ‘think-pair-share’ approach to help your pupils explore the meaning of work and employment and its importance.

Exploring where the money comes from to provide things at home is a good starting place for this topic.

In Activity 1 you ask your pupils to think about the different kinds of work in your community and discuss the difference between work and employment. Case Study 1 shows some pupils’ ideas about different types of employment.

Case Study 1: Group working and debate

Mr Petrus’ Grade 5 class in South Africa had been working on different forms of employment in the country. He now wanted them to focus on the local community.

Mr Petrus split the class into two. He asked one half to identify all the local employers and prepare an argument saying why it is better to be employed. He asked the other half of the class to identify different informal ways to make money and prepare an argument saying why it is better to earn money this way. After 20 minutes of preparation time, each group gave in their list and Mr Petrus wrote it on the board – making sure he didn’t duplicate ideas (see Resource 1: Ways of earning money for their list). They discussed the lists and realised that the work is the same in some cases, whether formal or informal, paid or unpaid.

In the next lesson, they held a debate, with each group nominating a speaker to present their argument. At the end, they held a vote on whether formal or informal employment is better. Even after the vote, the pupils continued to discuss the ideas, which pleased Mr Petrus.

Activity 1: Using think-pair-share to explore work activities

Use the ‘think-pair-share’ approach for pupils to identify different ways to make money and explore pupils’ employment opportunities.

- Ask your pupils to each think of the different ways there are to earn money. Give each pupil five minutes.

- Next, pair them with their neighbour and ask them to share their ideas. (If your pupils sit in desk groups of three, you could use threes instead of pairs.) They combine their ideas to make one list for each pair or three. Allow ten minutes.

- Ask each pair or three to give their ideas and list them on the board.

- Discuss the distinction between work and employment. Make sure they understand that people must work in their homes and on the land, and this is different from the work they do as employment for which they get paid.

- Ask the pupils to share how they would like to be employed in the future.

2. Exploring different kinds of work

Hearing from others how they do their different activities can help your pupils understand what variety of jobs there are and what they would like to do themselves. Inviting a guest to talk to them about what they do can help pupils understand how a particular kind of work is done. Taking pupils outside school will excite and motivate them and give real weight to how they see many jobs.

Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource provides guidelines on inviting visitors to your classroom.

Case Study 2: Talking about work and employment

To help her pupils develop the concepts of work and employment, and understand the importance of work, Standard 5 teacher Aisha talked to her pupils about work and the future. She found that most of her class wanted to go to university so that they could get good jobs and earn lots of money. Most of them wanted to move to the city.

To show her pupils real-life experiences, Aisha invited a local shopkeeper to come to the school and tell the pupils how he started his business. They learned that starting a shop and running it involves hard work. It also needs money; he got a loan from the government to start his business. He had paid back nearly all of his loan and would soon own his business.

Aisha also invited a friend of hers, Anyango, who used to live in their village but had gone to university and now worked in a bank in the city. Anyango explained that she had always wanted to work in a bank and she had studied hard to become an accountant.

After the visits, the class held a debate on whether it is better to stay in your village and run your own business or to go to university and get a job. The class had learned much about how work and employment were related to their efforts at school and in the wider community.

Activity 2: Visiting a local business

Take your class (or in smaller groups, in turns) to a local market and let them see what happens there. Pair the pupils carefully to make sure they stay focused on the task and do not get distracted while out of school. Prepare for the activity by arranging with some of the market traders to answer some questions from the pupils about their business. You will need to prepare a worksheet/questionnaire for your pupils (see Resource 2: Worksheet for the visit to the market). If you do not have the resources to make a worksheet, then in the previous lesson write some questions on the board and ask the pupils to copy them into their books – leaving spaces for the answers they will get at the market. Also, ask the pupils what they want to find out and add these questions to the list.

If you think it is more appropriate, you could take the class to a local bank or other place of employment, but you will still need to plan this and have some questions or tasks for them to do or ask when there. After the visit, the pupils can write up and/or discuss what they learned about work. Summarise these thoughts on the board.

3. Developing entrepreneurial skills

In the previous activities, your pupils have found out more about work and employment through group work and have also heard life experiences of people who are employed or earn a living.

In the Key Activity, you give pupils the opportunity to be involved in a task that will extend their skills and which they might be able to use to gain an income.

Case Study 3 shows how one teacher set up a mini-enterprise to give her pupils experience of work and employment.

Case Study 3: Using local recycled materials to sew and make an income

Mrs Maingi is a vocational skills teacher in a primary school in a small town in Kenya. Near the school there are three tailoring shops. The area around the tailoring shops was littered with small pieces of cloth that the tailors had thrown away. Mrs Maingi and her class thought that they could use the pieces of cloth to make useful items during their needlework lessons. She asked the tailors to collect all the pieces of cloth for her instead of throwing them away.

Mrs Maingi used the cloth to teach the pupils how to sew. They cut, neatly hemmed and stitched them to make handkerchiefs, scarves and small tablecloths. Since most of the pupils did not have a handkerchief or scarf, each pupil was given one. The rest of the handkerchiefs and the small tablecloths were sold at very reasonable prices in school and the village.

One boy and one girl were chosen to record how much money they were paid. They also had to pay for the needles and threads they used. The profit was used to buy sugar to put into their porridge. The pupils were very happy because there was no more littering from the tailors and they could now take porridge with sugar.

Key Activity: Working for our school

It is now time to put all your pupils’ knowledge about work and employment to the test by doing an activity that will benefit the school or home. Resource 3: Barrina Primary School, Kenya, school garden gives an example of a school in Kenya making a garden to provide food and sell surplus as part of a project.

- Discuss and identify activities that they can do as projects to help them develop skills, while at the same time being beneficial to the school/home. Decide together which are the two best ideas to carry out. Examples could be: making baskets, mats, ropes or brooms, or collecting plastic bags and bottles for recycling. The kind of activity will depend on the context of the school.

- Pupils choose to work on one of the two selected projects. You will need to help them in planning their project and collecting the resources. Local experts and other community members could help and advise you on what to do.

- Discuss with the pupils what they can do with the products they get from their project (whether they can be used in school, at home or possibly sold to make money).

- Discuss with the pupils the usefulness of their projects and the skills they have developed.

- You might want to plan a day to sell some of your goods and use the profits to buy things that would benefit the whole class.

- Point out to the pupils that the activities they do both at home and in school as work can help them develop skills that they can use to gain employment in the future.

Resource 1: Ways of earning money – Mr Petrus’ class list

![]() Example of pupils' work

Example of pupils' work

Formal ways to earn money

- Work for the government.

- Work for a company.

- Work for a small-business person.

- Run own business.

- Make things.

- Work for an NGO.

- Work at a clinic.

- Be a teacher.

- Build furniture.

- Work in a garage.

- Be a plumber.

Informal ways to earn money

- Sell things.

- Grow things.

- Sell hot food to workers.

- Sew.

- Fix cars.

- Street trading.

- Be a local guide.

- Be a domestic worker.

- Be a gardener.

Resource 2: Worksheet for the visit to the market

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

| 1. | How many market stalls are there in the market? |

| |

| |

| |

| 2. | What different goods are sold there? |

| |

| |

| |

| 3. | Who owns/is in charge of the market? |

| |

| |

| |

| 4. | What are the opening hours? |

| |

| |

| |

| 5. | Where is the next nearest market? |

| |

| |

|

For one market trader, pupils could ask:

| 1. | How did you start your business? |

| |

| |

| |

| 2. | Where do the goods come from that you sell? |

| |

| |

| |

| 3. | How do you calculate your selling prices? |

| |

| |

| |

| 4. | How do you calculate your profits? |

| |

| |

| 5. | What form of transport do you use to come to market? |

| |

| |

| |

| 6. | How far from the market do you live? |

| |

| |

| 7. | What is the biggest problem for the market traders? |

| |

| |

|

Resource 3: Barrina Primary School, Kenya, school garden

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

The garden was established to grow food crops. Teachers have been encouraged to develop ideas for curriculum activities through the designing, development and management of the gardens. Other schools in India and the UK are also doing the same so they can share ideas. Students from the age of 9 to 13 are participating in the scheme.

During lessons students consider questions about:

- where our food comes from;

- how land is used;

- how our lives are interconnected across the globe through food, looking at issues of Fair Trade;

- levels of nutrition and malnutrition in all communities;

- how diets vary in different countries;

- how social, economic and environmental factors influence nutrition and food security;

- the impact of growing food locally or importing food from around the world.

Attitudes to growing food vary around the world. Many children in the West know little about how food is produced or where it comes from. This lack of understanding about the connection between food, lifestyles and nutrition is often reflected in diet. Most children in rural Africa and India know how food is produced, but may consider farming as a low-status occupation.

Gardens for Life, which is the project that this school joined, aims to increase pupils’ knowledge and awareness of food and their understanding of other ways of life around the world. As the gardens have developed, the pupils have gained hands-on skills in horticulture. Improved practices have been introduced. For example, water catchment schemes have resulted in improved yields. In some cases, pumps and micro-irrigation systems have been installed. Learning has not been limited to horticulture – experiences from the gardens are brought back into the classroom in other curriculum areas such as science, geography, global citizenship and maths. Materials are now being developed to support these curriculum areas.

The produce from the gardens is used to provide meals for schoolchildren, providing a vital component in their diet as sometimes this is the main meal that they get during the day. Food security is enhanced as these gardens are able to provide a regular supply of food. Any surplus provides profits for the school when it is sold to the local community where it is much appreciated. Pupils can see that viable businesses can be based on horticulture. Links with the local community are being strengthened as knowledge and experiences between the pupils and farmers are shared.

Adapted from: http://www.handsontv.info (Accessed 2008)

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Photographs and images

The children from Barrina Primary School, Kenya, are digging their garden in preparation for planting:Original source: http://www.handsontv.info

Text

Resource 3: Barrina Primary School, Kenya, school garden: Adapted from: http://www.handsontv.info (Accessed 2008)

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Section 4 : Exploring the environment

Key Focus Question: How can you gather data to develop pupils’ learning about the environment?

Keywords: environment; data gathering; assessment; diaries; real-life stories

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used real-life stories, data gathering and diaries to develop understanding of environmental issues;

- planned, carried out and reflected on an action on a local environmental issue;

- assessed the learning of the class and the success of the project.

Introduction

A major issue across the world is the impact that people have on their environment. If we use up or misuse resources and pollute the environment we have a negative effect on wildlife and crops, and we run the risk of damaging the world for future generations.

As a teacher, and a responsible citizen, you need to be aware of environmental matters and act as a role model for your pupils as well as helping them to understand the issues. You can do this best by giving them activities that involve gathering information about the environment, both locally and more widely, and using what they find out to think about the consequences of different actions.

1. Focus on the local environment

Learning about some of the complex concepts about the environment needs you as the teacher to break down the ideas into smaller parts and build up the picture in a logical way. Pupils find this easier if you take think about the ideas they already have and you use the local environment to show them how these ideas relate to their situation.

There are many ways to do this. This first part of the section focuses on gathering information from your pupils’ own experiences to explore the concepts and their own responsibilities and rights.

Case Study 1: Researching local water use

Mrs Namhlane in Nigeria was starting a topic on the local environment with her large Primary 2 class, looking at the importance of water in everyone’s life.

To stimulate her pupils’ interest in the topic, she decided to set up a class research project. First, she asked them to get into groups of six to eight people who lived in the same part of the community and told them that there were three people coming into school next day – one from each part of the community – to talk about how they got and used water. She asked them to think about and write down questions to ask. These area groups shared their questions together so that each area group could check they had thought about all aspects.

The next day, each visitor talked, either in the classroom or outside under a tree, with pupils from their area. The groups asked their questions in different ways – in one group different pupils asked one question each, in another group a girl and a boy asked all the questions and the others took notes.

After the visit, pupils were asked to list three important things they had found out and report to the whole class. Mrs Namhlane asked each group in turn to tell what they had found out but not to repeat any answer already recorded on the board.

They then discussed the problems that there were about water and thought of possible solutions (see Resource 1: Problems of getting water).

Activity 1: Keeping a ‘water diary’

Ask your pupils to keep a ‘water diary’ for one week. They will record (perhaps on a wall chart) how much water they use and what they use it for (see Resource 2: Water usage diary for a possible template).

After a week, ask them to work in groups and to list all the uses in their group and then put them in the order of which activities use most water and which use least. Display each list on the wall and allow them to read each other’s lists before having a final session together discussing the issues about water in their area.

You may want to consider questions like: Where does our water come from? Does everyone have access to water? Is our water clean and safe? How could our water services be improved? How can we help?

You could also link this activity to number work (by looking at the data – the amount of water used), to science (why water is essential to life) and to social studies (the problems of providing water in some parts of Africa).

2. Using stories to explore environmental issues

Drawing is a useful way to explore pupils’ ideas about any topic. It allows them to show their ideas without having to speak aloud or be able to write. It is especially useful with young pupils and provides a way for them to talk about their ideas. The drawings do not have to be of a high standard but have to tell a story or show an idea.

Using stories is another way of encouraging pupils to think more deeply about a problem. It removes the focus from the individual and allows pupils to talk more openly. Stories can also provide a wider perspective for pupils and give them inspiration. Case Study 2 and Activity 2 show how you could use both techniques in your classroom.

Case Study 2: Stories and environmental issues

Mr Ngede read Resource 3: The story of the selfish farmer to his class to stimulate their ideas about the Earth and its resources.

He then gave his pupils a small piece of paper and asked them to draw a picture of ‘why the farmer was selfish’.

He explained the idea carefully and encouraged them not to copy, but think of their own ideas. As the pupils finished, they stuck their pictures on the wall. Mr Ngede asked some pupils to say what their drawings were about and he tried to guess what some were. The pupils enjoyed this very much.

Next, he led a discussion about how important it was for everyone to look after the land. They listed together on the board how people in the local community used the land and looked after it.

He then asked them some questions, which they discussed in groups. For example:

- How did the people use the land?

- Did they look after it?

- In what ways could the farmer have looked after his land?

- Who did the work?

- Was the land productive? If so, why? If not, why not?

- How could they improve the way they looked after the land?

More can be found in Resource 4: Questions concerning use of the land.

As a class, they thought about the questions and shared some ideas.

At the end of the day, Mr Ngede asked the pupils to look on their way home at all the different ways the land was being used and to come back the next day with any that could be added to their list.

Activity 2: Leaders and the environment

This activity looks more widely at the importance of looking after our environment. Resource 5: Sebastian Chuwa tells the story of a Tanzanian man who has inspired communities to come together to solve environmental problems. Read this before you plan your lesson.

- Tell your class this story. On the wall have a number of words spelled out clearly, for example ‘conservation’.

- After you have read the story, discuss these words and their meanings.

- Ask your pupils, in pairs, to imagine themselves as someone like Sebastian Chuwa. What particular environmental issue would they like to do something about? How would they do this? Move around the class and ask pairs with good ideas to explain their ideas to the rest of the class.

- Ask them to look closely at their local environment as they go home and see if there are other issues they had not noticed before and share these the next day. Make a list of their five favourite issues.

3. Organising a campaign

As a teacher, you need to help pupils understand their responsibility to their environment in ways that stimulate their interest and develop a caring attitude towards it. In the Key Activity, a poster campaign is used as a stimulus and in Case Study 3, a small-scale project is described that shows how different groups can interact in order to make a difference.

As the pupils work through such a project, your role is to be well prepared to anticipate some of their needs and provide resources to support their learning. If you have a large class, you will have to think how you can involve all your pupils and perhaps divide the tasks up between groups. With younger pupils, you may have to plan to do something on a much smaller scale and involve some members of the community in helping you more.

Case Study 3: Planning and carrying out a class ‘clean-up’ campaign

A class in Ngombe school in Iringa decided to launch a ‘clean-up’ campaign. Their teacher Mrs Mboya had been working on a cross-curricular theme with the title ‘looking after our land’.

Having spent one morning walking around the school and the area just outside it, Mrs Mboya and her class discussed what they had seen. They listed everything they liked about the area and also those areas or things they would like to change or improve.

They decided they could work on two small areas to clean up the environment – the school playground and the local stream. The class was divided into two groups with two teams working in each area. The teams discussed what they could do and then shared their ideas with their other team. They agreed who would do which tasks and then each team worked out its own action plan for the week, around school hours.

The class carried out the clean-up over a one-week period. They then made a display in the school hall that showed:

- the amount and type of material collected in the clean-up;

- their plans for keeping the environment attractive and litter-free in the future;

- how to dispose of the litter, including recycling and reusing some of it and burning or burying some.

The assembly went well and many pupils from other classes were pleased at the work done and helped to keep the school area tidier.

Key Activity: Taking action on environmental issues

This activity builds on your pupils’ raised awareness of litter and waste management and takes a step-by-step approach to learning through action.

Step 1 – Ask the class (perhaps working in pairs) to identify litter and waste issues in and around the school. Select one issue (probably the one that was mentioned the most).

Step 2 – Work with the class to design a ‘plan of action’. To do this, ask each pair to suggest ways of solving the problem. Make sure that the agreed plan of action you develop is realistic and can be attempted by the class. Give out tasks to groups of pupils.

Make the plan into a large poster with deadlines that can be displayed on the class walls.

Step 3 – Take action: this might involve days or months of work but make sure each group keeps a record of what they do, when and in which order.

Step 4 – As they complete each part of the action plan, ask them to record their progress on the poster.

Step 5 – On completion, reflect on the success of the action with the class. What went well? What did they learn? What were the problems? What could they do to extend this idea? Is the area staying clean?

Resource 1: Problems of getting water

![]() Example of pupils' work

Example of pupils' work

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

- Long distances to travel to obtain water.

- Leaving younger children behind to get water.

- Pupils out of school to collect water.

- Is the water clean and safe?

- Size of containers to carry water and weight of water to carry over long distances.

- Time taken to obtain water stops people doing other things.

- The water collected may be contaminated by poor sanitation and animals’ use.

- Open to infection by water-borne diseases.

- Drought can restrict access to clean water.

- Lack of infrastructure e.g. pipes and storage containers to capture rainwater etc.

- Lack of systems to purify water.

- Lack of education about ways to use and keep safe natural water resources.

- No sustained access to water.

Resource 2: Water usage diary

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

Each time you use water to have a drink or cook, etc. put a tick in the appropriate box.

| Drinking | Cooking | Washing | Cleaning the house | Other | |

| Monday | |||||

| Tuesday | |||||

| Wednesday | |||||

| Thursday | |||||

| Friday |

Resource 3: The story of the selfish farmer

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

There was once a young farmer, who had a wife and two children, who lived in a small village. The farmer had inherited his farm from his hardworking grandfather whom he loved. While being sad at the death of his grandfather, the farmer was pleased to be his own boss and own all the land.

He was a hardworking young man and he maintained the farm as well, if not better, than his grandfather. He had learned a lot from his grandfather but also had learned well at school and read all about different ways to preserve water and tend the ground, which increased his crops. However, he was not like his grandfather in that he would not share his ideas or extra produce with other farmers and growers in the village.

The villagers were surprised when they went to ask for some seeds or advice to be told to get off his land. His wife was not happy about this but respected his views. The villagers watched what he did and some tried to copy the things he did but without as much success. Others just laughed or moaned about what he was doing.

One very dry season, the crops in the village did not do well. There was little water as the stream had dried up and there was a long walk of over six kilometres to the next source of water, which meant that only water for drinking was brought back.

The selfish farmer, however, had plenty of water and food, but did not help villagers who came to seek help. His wife begged him but he did not change his mind. He had put up guttering and sheets to catch the rainwater and stored this in big drums that he had collected so when the drought came he was able to water his plants, which grew as well as ever.

As it got hotter and hotter and drier and drier, people’s crops began to fail and many were hungry. The wife tried to persuade her husband to help the villagers. The children tried to persuade their father, but he would not listen. He said he had worked hard and it was his and the others were lazy or had not planned ahead.

However, one day, a very thin and ragged man came to the farm to ask for food for his ill wife. The farmer shouted at him to go away but his wife stopped him and said: ‘Don’t you recognise your cousin?’ The farmer was shocked at how thin and old his cousin looked. The cousin explained how he’d tried to save water but failed, and so his crops failed.

The farmer told him what he could do next time. But his wife said he is too weak to do this unless you give him and his wife food. The farmer relented and gave the cousin food. The cousin returned a week later saying his wife was getting better and could he have more food. The farmer was going to say no but his wife told him that they were so hungry it would not be enough to give just one lot of food. The farmer gave the food and over the next few days he slowly changed his ideas as he thought about how selfish and thoughtless he had been to his grandfather’s memory and to his neighbours. So he asked the villagers to his farm and shared his food with them and promised to help them prepare better for the next crops.

Resource 4: Questions concerning use of the land

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

| 1. | How many different ways can we use the land? Make a list. |

| |

| |

| 2. | Why is it important to look after the land? |

| |

| |

| 3. | Why are some people more selfish than others? Why should we share our land? |

| |

| |

| 4. | How can we encourage people to share? Should we share everything? |

| |

| |

| 5. | Do we look after our land well? |

| |

| |

| 6. | Who else do we share our land with? |

| |

| |

| 7. | How can we look after the land better? |

| |

| |

| 8. | What can we, as a class, do to look after the school land? |

|

Resource 5: Sebastian Chuwa

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Sebastian Chuwa is a man with a vision for his country, his people and the future generations who will inherit their legacy. For 30 years he has been actively studying environmental problems in his east African homeland of Tanzania, and the solutions he has found offer results that benefit not only the land, but all the populations that depend on it for life and sustenance. His methods are based on the two primary objectives of community activism – organising people to address their problems at a local level, and youth education – influencing the teaching of conservation in schools, beginning at the primary level.

He has inspired large groups of community volunteers to come together to solve not only their environmental problems, but problems of poverty alleviation, women’s empowerment and youth employment within the area of Kilimanjaro Region in northern Tanzania. His efforts on behalf of African blackwood have created the first large-scale replanting effort of the species. Because of the establishment of multiple community nurseries and numerous cooperative projects geared towards reforestation over the past decade, in 2004 the ABCP and the youth groups associated with Sebastian’s work celebrated the planting of one million trees. The ever-expanding nature of his work has given him and his community a reputation as leaders in the field of Tanzanian conservation.

History of the African Blackwood Conservation Project

In 1996, James Harris, an ornamental turner from Texas, USA, and Sebastian Chuwa founded the African Blackwood Conservation Project (ABCP), to establish educational and replanting efforts for the botanical species Dalbergia melanoxylon, known as mpingo in its home range of eastern Africa. The wood of mpingo is widely used by African carvers and by European instrument manufacturers for the production of clarinets, flutes, oboes, bagpipes and piccolos. Because of overharvesting and the lack of any efforts directed towards replanting the species, its continued existence is threatened.

In 1995, James Harris, who uses mpingo in his craft, saw The Tree of Music film in the US and determined to do something for the conservation of the species. He made contact with Sebastian by mail and proposed a joint effort: he would launch a fundraising effort among woodworkers, musicians and conservationists of the western world, and send the money to Sebastian to start tree nurseries in Tanzania. The project was enthusiastically endorsed by Mr Chuwa. Since that first contact, the ABCP has become a leading force for mpingo conservation in northern Tanzania, founding nurseries for the production of large numbers of mpingo seedlings and raising awareness about the importance of the species internationally.

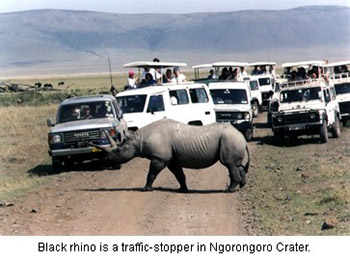

Conservation at Ngorongoro

Sebastian Chuwa’s childhood home was on the southern slope of Mt Kilimanjaro at 4,900’ elevation. He learned to love nature at an early age from his father and mentor, Michael Iwaku Chuwa, who was a herbalist. Together they would take long forays into the forests to collect plants for the remedies his father used in his work. On these expeditions over many years he learned the names of the plants and trees of Kilimanjaro’s abundant flora. His love for the natural world continues to this day and is the guiding force behind his work.

After finishing secondary school, he studied at Mweka College of Wildlife Management and after his graduation was hired as a conservator at Ngorongoro Conservation Area. During his 17 years of employment there, he studied and catalogued the plants of the area, discovering four new species (of which two are named in his honour) and assembling a herbarium of 30,000 plants at the visitor’s centre for the use of visitors and staff personnel. Because of his considerable knowledge about the flora of the area, he worked with Mary Leakey at nearby Oldavai Gorge, identifying plants in the area of the Leakey early hominid discoveries. At Ngorongoro, he also instituted a successful protection programme for the endangered black rhinoceros, which was duplicated in other African locales.

Ngorongoro Park is a co-management area where the Maasai communities still live with their cattle herds. During his employment at the park, Sebastian worked closely with the Maasai, studying their medicinal remedies and setting up tree nurseries for their use. He also set up the first youth conservation education programme in Tanzania for Maasai children, focusing on practical activities like establishing tree seedling nurseries and replanting programmes. This club was so successful that it became the blueprint for a nationwide movement, called Malihai Clubs of Tanzania (see below), established in 1985, with offices at NgorongoroPark headquarters in Arusha and now operating nationwide with about 1,000 clubs.

Offices and awards

In 1999, Sebastian was honoured with an appointment as chairman of Kilimanjaro Environmental Conservation Management Trust Fund by the Regional Government Authority of Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. This office automatically makes him a member of the Regional Environmental Conservation Committee. His valuable contributions to environmental conservation will be amplified through this position.

Adapted from: http://www.blackwoodconservation.org (Accessed 2008)

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Text

History of the African Blackwood Conservation Project: Adapted from: http://www.blackwoodconservation.org (Accessed 2008)