Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Monday, 9 March 2026, 9:25 PM

TESSA Inclusive Education Toolkit: A guide to the education and training of teachers in Inclusive Education

TESSA Inclusive Education Toolkit

A guide to the education and training of teachers in inclusive education

Welcome to the Inclusive Education Toolkit!

This toolkit supports the training of teachers in inclusive education. It is designed for instructors and trainers, who are training teachers or are working with other trainers and teachers in training institutions, schools, classes, NGOs, or any other organisation.

You can use it for initial training and to support the continuing professional development of teachers, mentors, educational inspectors, educational advisors, principals, and other specialists and workers in education.

Teachers can also use it, working on their own or in teams.

How can I use this toolkit?

If you are a trainer, you can select and integrate appropriate sections, case studies or activities into training courses or programmes. You may also duplicate and distribute relevant sections.

If you are a teacher, you can look for sections, case studies or activities that will help you to resolve a challenge you have encountered in your classroom.

Why use the TESSA toolkit for teacher training in inclusive education?

As trainers and supervisors, it is your responsibility to educate and train teachers who will ensure that the universal rights of children as described in the 1990 Convention on the Rights of the Child are respected.

State Parties recognise the right of the child to education (…) without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of the child’s or his or her parent’s or legal guardian’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status. (UNICEF, 1990)

Welcoming all children ‘without discrimination’ means that in a classroom there will be, for example, children with physical or sensory disabilities, gifted children, children with learning difficulties, girls, boys, children from minority ethnic groups, and the teaching will need to cater for all children’s individual development as well as the fulfilment of their potential

Our main objective

To introduce the inclusive pedagogy that is at the heart of TESSA to educators, educational supervisors, teachers (in training) and the teachers’ schools, and to facilitate the planning, use and evaluation of inclusive teaching practices through the use of active pedagogy.

Aims of the TESSA Inclusive Education Toolkit

- Enable users to explore and understand the meaning of ‘inclusive education’.

- Serve as a guide to enable all pupils in the class to be full members of the class, to respect each other, to learn, and to fulfil their potential.

- Offer strategies to allow for inclusive teaching and provide support to all learners, including those with disabilities.

- Provide a set of teacher training tools that are published under Creative Commons Licenses and can be adapted and used in different environments and contexts.

How does this toolkit work?

This toolkit provides resources that you will be able to use to build teachers’ ability:

- to think about ways they can facilitate the inclusion of all children in learning, in the classroom, in the school and in the community.

- to include all children in the learning process so that they can grow and to achieve their full potential.

- to incorporate the strategies illustrated in the TESSA educational materials (based on the premises of active, inclusive and participatory pedagogy) into their teaching practice.

This toolkit is not intended to be a module or a procedural document. It is not a book that you read and work through from cover to cover. It is a collection of tools to refer to where certain challenges occur in the process of teaching practice supervision. The tools are shown on the diagram on the entry page of the toolkit and they can be accessed in any order you wish.

The toolkit contains activities that may be conducted individually or in collaboration with other teachers. We encourage you to evaluate your own needs and those of your teachers, and to find in the toolkit components that best meet those needs: do they concern teacher behaviour, the physical environment of the classroom, teaching techniques, the relationship between the school and the community, etc.? Browse through the titles and select the relevant chapters.

The toolkit can also be used as a reference document when organising and running workshops on inclusive education.

Getting Ready

Before consulting the chapters in the Inclusive Education Toolkit, it will be helpful to familiarise yourself with TESSA (Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa) and with the concept of active learning. This is the purpose of the first activity.

Activity 1: Getting to know the TESSA resources and active learning

This activity will allow you to get acquainted with the TESSA resources.

- Download the chapter ‘About TESSA’ on the Teaching Practice Supervisor’s Toolkit page on the TESSA website.

Read the chapter and do Activities 8 and 9 in the Chapter .

The icons used in this toolkit:

To enable you navigate this toolkit easily, we have used the following pictograms:

![]() Other useful resources

Other useful resources

This symbol refers to more detailed and accessible texts on the topic in hand. You do not have to read everything, but the resources are available for you to improve your understanding and your role in inclusive and active learning.

![]() Complementary TESSA resources

Complementary TESSA resources

This symbol refers to other TESSA resources that complement the on-going work.

![]() Create your own collections of strategies

Create your own collections of strategies

During your work through the different chapters of the toolkit, you will be asked to collect ideas and strategies that will help you to vary your teaching. Collect them for yourself and share your collections with colleagues if you wish.

![]() Activity based on audio resources

Activity based on audio resources

1. Different types of schools

At the end of this chapter, you will:

- have enabled teachers to explore, understand, and appreciate the difference between education in mainstream schools, specialised, integrative and inclusive schools.

There are several models of education that allow all children, ‘without any distinction’, to learn.

Research shows that there are different types of schools that offer different approaches towards providing quality education for all.

Activity 2: What do different schools do to allow all children to learn?

This activity will enable teachers to understand the differences between different types of schools and to begin to develop their own definition of inclusive education.

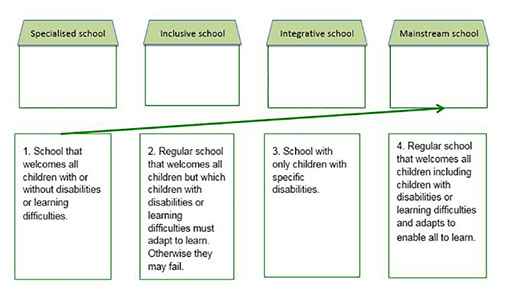

- Read below the definitions of the different schools and match them with the names of the schools.

- Write your own definition for ‘Inclusive education’.

What answers did you give? The following table will help you check your answers.

| Special education | Regular education | Integrative education | Inclusive education | |

| Are allowed | Children with specific impairments | All children | All children, but they must change to fit the system | All children, with their individuality and differences, different levels of ability, different ethnic groups, girls and boys, valid or with disabilities |

| Curriculum and methods | Everything is adapted to meet the children’s specific needs | Everything is regular | The children need to adapt, otherwise they might fail | Everything is designed so that every child can learn and reach her/his full potential |

| The teachers | Specialised | Regular | Follow the system that remains the same | Adapt the curriculum, methods, and system to the needs of the children |

| Schools (no. of the definitions for Activity 1) | Specialised schools (3) | Regular schools (1) | Integrative schools (2) | Inclusive schools (4) |

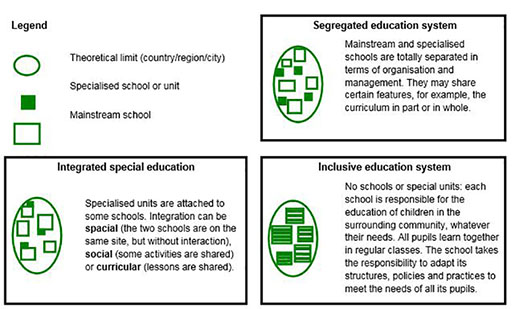

This diagram shows a possible illustration of the different types of educational systems.

Now compare your definition of ‘inclusive education’ given in Activity 2 to the definitions below. Highlight characteristics you believe to be important and complete your own definition.

Inclusive education means education in which all children are welcome in the same classroom and provided with high-quality instruction and the support tools needed to succeed. In practice this requires helping schools and school systems to adapt to the needs [of] each individual child, rather than trying to ‘fix the child in order to fit the system.’ It also involves convincing parents, teachers, and other pupils that children with disabilities should be accepted and allowed to attend school alongside their peers.

(Handicap International, n.d.)

If the right to education for all is to become a reality, we must ensure that all learners have access to quality education that meets basic learning needs and enriches lives. (…) The UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education (1960) and other international human rights treaties prohibit any exclusion from or limitation to educational opportunities on the bases of socially ascribed or perceived differences, such as sex, ethnic origin, language, religion, nationality, social origin, economic condition, ability, etc. Education is not simply about making schools available for those who are already able to access them. It is about being proactive in identifying the barriers and obstacles learners encounter in attempting to access opportunities for quality education, as well as in removing those barriers and obstacles that lead to exclusion.

Did you note the following characteristics in your definition of inclusive education?

|

|

Inclusive schools allow all pupils to learn together, regardless of their gender, race, faith, wealth, origin, disability or any other condition.

To do this, schools must be adapted to meet every child’s needs. This means having an in-depth knowledge of the pupils and adapting learning techniques and buildings accordingly. Moreover, it is important to change the mindset and attitudes of teachers, pupils and the entire educational community. The basic principle is that we are all capable of learning and at the highest levels given the right tools/opportunity/support – after all Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton and Thomas Edison were children with special educational needs! They all had Asperger’s Syndrome.

2. The inclusive teacher’s attitude and behaviour

At the end of this chapter, you will have enabled teachers to develop techniques to ensure that:

- teachers and pupils respect everybody’s individuality

- teachers and pupils use an inclusive language

- pupils start developing self-esteem

- pupils feel included in the learning community

- pupils feel valued

- teachers help promote pupils’ emotional well-being.

What type of teacher do you wish to train? Are the teachers with whom you work considerate about their own attitude and behaviour? The questionnaire Auditing an Inclusive Teacher’s behaviour invites teachers to reflect their own behaviour in the classroom and on how it impacts on the way pupils learn.

You could ask teachers to fill in this questionnaire at the beginning of their training and again at the end of the training period, so that they can reflect on the values they bring and what can help them to modify these values and their behaviours if necessary.

Before asking the teachers in training to fill in this questionnaire, fill it out yourself so that you can guide them.

2.1 An inclusive teacher respects the individuality of each child

An inclusive teacher helps children to develop self-confidence and self-esteem and to feel included in the learning community. It starts with the language used by everybody in the classroom, teachers and pupils, and by the way the language is used. The teacher must ask himself:

- Does the language used by all in the class to speak to and about the child show she/he is valued?

- Do my language and my attitude demonstrate that I respect this person, her/his identity and rights?

- Do I value the child when I interact with her/him?

- Do I know the appropriate terms to use when I name children who have a disability and to talk of their disability?

The language used is often loaded with emotions, particularly for children who have a disability. Let’s reflect on Marie’s case.

Case study 1: Mr Dumee helps Marie regain her self-confidence

In a school in Mauritius, the young Marie has one leg shorter than the other. In class and in school, peers call her ‘One and a half hour’. Marie is really sad because of this nickname. At the beginning, she did try to resist being called so, but she was bullied and hit by older boys. She resigned to settle for the loser’s peace rather than struggle eternally. Marie became withdrawn and lost all her happiness. In class, she did not dare to raise her hand to answer questions as she was afraid that the slightest mistake will make other children laugh at her and that she would have to bear remarks like: ‘One and a half hour can only say stupid things.’ Mr Dumee, the teacher, could not understand why Marie would not participate in class even though her results were always good.

Activity 3: How to help Marie?

This activity will enable teachers to offer solutions to support Marie.

- First, ask teachers to work individually and to quickly note all the ideas they have to support Marie.

- Then, ask teachers to work in pairs and share their suggestions and discuss on how to help Marie to gain self-confidence.

If you are a teacher working alone, quickly note down all the ideas that come to mind and then, for each idea given, indicate how this would help Marie to gain self-confidence

Does Mr Dumee’s suggestion figure among your ideas?

Mr Dumee talked with Marie and then organised an activity for the whole class. He asked all the pupils to write a harsh word and a kind word on two different pieces of paper. He then collected the papers and turned them face down on the table so that the children could not see what was written on them. All children were made to choose one without looking at it and this nickname was pinned on their back. Those who had harsh words were profusely mocked by their classmates. Mr Dumee asked the children how they felt when they were called by these names and when the others mocked them. He then asked those who got nice words how they felt.

He concluded by asking pupils to think on how Marie must have felt when they called her ‘One and a half hour’. He motivated the pupils to present their apologies to Marie and to decide on using nicer words when they talk to her or when they talk about her.

![]() You must have noticed that Mr Dumee did not moralise, but instead helped the children to develop empathy towards their classmate. The idea was to make them feel what Marie felt, which helped them to appreciate and understand that in spite of our differences we do have similar feelings in similar situations.

You must have noticed that Mr Dumee did not moralise, but instead helped the children to develop empathy towards their classmate. The idea was to make them feel what Marie felt, which helped them to appreciate and understand that in spite of our differences we do have similar feelings in similar situations.

2.2 Using appropriate words when talking about disabled children and their disability

The use of respectful words is not only important in class and in school but also in the community at large. It promotes the development of self-confidence and self-esteem, and allows the child to feel included in class and in the community. This also denotes the respect of human rights. Positive language helps the child to gain the right status by promoting a positive atmosphere, which is necessary for the acquisition of knowledge. For this to happen, both teachers and peers should banish negative-sounding words, including those that equate a disability to an illness. They must avoid nicknames and call all children by their own names. They need to avoid all words that may hurt, and adopt only positive or neutral words.

Activity 4: Avoiding words that hurt

![]() In this activity teachers will create a list of appropriate terms to use to speak about disabilities and people with disabilities. It is suggested that they create a table to highlight terms to avoid and terms to use. This can be done as a poster or on a computer.

In this activity teachers will create a list of appropriate terms to use to speak about disabilities and people with disabilities. It is suggested that they create a table to highlight terms to avoid and terms to use. This can be done as a poster or on a computer.

- Using a large piece of paper, or on a computer with a word-processing programme, make two columns labelled ‘Avoid’ and ‘Say’. Then fill in both columns with words that you can think of to speak about disabilities and people with disabilities.

- A few examples have been done already. Teachers should work together to think of more words that are commonly used and more appropriate alterntives.

| AVOID | SAY |

| This person is retarded. He is an imbecile | A disabled person |

| The mongol person | This person is deaf |

| This person is affected by deafness | This person has learning difficulties |

| A handicapped person | The person who uses a wheelchair |

| The person who is confined to a wheelchair | The child who has Down's Syndrome |

There is not an exhaustive list of respectful words to be adopted in class, at school, and in the community. Keep the table and

- when you encounter new words that might help you to use a more inclusive language, add them to your list;

- when you encounter words that might shock you, note them down too, and try to find more neutral expressions that are not hurtful.

The inclusive teacher strives to find the language that conveys respect to everyone and includes every child in the class. The aim is to provide an environment free from discrimination, frustration and anxiety.

The language used to talk about disabilities is ever changing. It is the teacher’s responsibility to be attentive to change and to adapt accordingly.

2.3 An inclusive teacher is aware of the different needs of pupils

Activity 5: A class where the teacher’s behaviour enables everyone to feel included

Activity 5: A class where the teacher’s behaviour enables everyone to feel included

Through this activity, teachers will reflect on their behaviour and how it might impact the inclusion of all pupils.

- Download the resource Keep your mouth shut! from the section Equal opportunities in the Audio resources on the TESSA website.

- Listen to the short play. As a teacher, what lessons do you draw from it in regards to your responsibility concerning the handling of instances of disability in your class?

Teachers should observe their pupils to get to know their strengths, weaknesses, learning styles and personalities. This will enable them to notice less apparent deficiencies and take appropriate actions. You will learn about many of these actions in the next chapters of this toolkit. Knowing your pupils well will enable you to treat everyone fairly in the class.

2.4 An inclusive teacher helps pupils to gain self-confidence and self-esteem

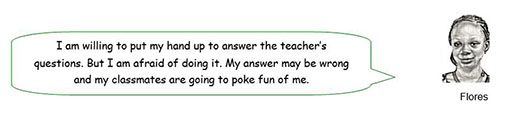

A major barrier in the learning and participation of children in classroom activities is the lack of self-esteem and self-confidence. You have probably noticed that this is the case for Flores.

In supporting learners, the inclusive teacher has a crucial role to play in encouraging all children’s social and emotional learning. Atmosphere and dynamics in the classroom and school can be managed in order to encourage self-confidence and participation.

Activity 6: How to help pupils appreciate and respect their similarities and differences

This activity will provide teachers with examples of activities conducive to creating a positive atmosphere in the classroom.

- Download Section 1 of Module 1 of ‘Life Skills (Primary)’ in the Subject resources area of the TESSA website. It shows how one teacher encouraged her class to include an albino child.

- Read this section and make notes of the techniques used to help pupils to explore who they are, help them to recognise their similarities and differences, and to show mutual respect.

- How will these activities help the teachers in training develop their pupils’ self-confidence and self-esteem?

- Add other similar activities that could be used for the same purpose with pupils.

Children need to understand and talk about their differences and similarities and must consider them as a natural part of society. As a teacher you have an important role to play in helping children to realise that their opinions, perceptions and emotions can be different but that they all are important parts of society. Diversity in society is enriching. As a teacher you must model this by adopting a fair attitude towards all children and organise activities that allow them to work together, interact and build their learning together. You need to encourage inclusive social behaviours such as mutual appreciation and respect, listening, tolerance and empathy.

2.5 An inclusive teacher helps pupils to feel included in the learning community

Activity 7: How to develop community life

This activity will enable teachers to think about strategies to develop pupils’ understanding of community life rules.

- Download Section 1 of Module 3 of ‘Life Skills (Primary)’ in the Subject resources area of the TESSA website.

- While reading this section, consider the following question: Can discussions in the classroom and in the community on rights and duties in the family and responsibilities within a community contribute to the development of self-confidence and self-esteem in learners?

- How could you adapt the key activity: ‘Presenting learning in a school assembly’ to better serve your purpose?

Children will not acquire knowledge unless they feel safe in the classroom and therefore free to express their opinions without the fear of being laughed at by their classmates, or being punished by the teacher. To create a safe environment, teachers need to examine their own values, attitudes, behaviours and actions. In addition, they also need to be aware of the family and social environment of the child, and enable all learners to feel valued.

2.6 An inclusive teacher acknowledges the contribution of each child

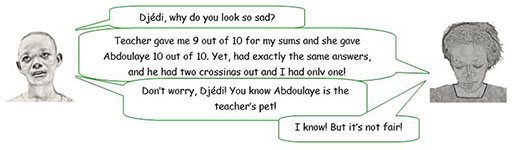

Developing (or restoring) self-confidence and self-esteem in children also entails recognising their contributions, however small they may be. How can the teacher do this? Have a look at the exercise Mr Attikou gave his class.

Case study 2: When mistakes give the best grades

At the Safo School in Niger, Mr Attikou asked his pupils to take a piece of paper for a spelling test. He specified that they should not write their names on the piece of paper. After the test, Mr Attikou gathered the papers and distributed them again making sure that no child received her/his own work. Then, he wrote the correct spellings on the board and asked the children to mark the test they had received. He also asked them to write their names on the paper they were correcting. If they found all the mistakes, they would score 10 out of 10. If a mistake was left out, they would earn 9 out of 10 and so forth. That day, all of Mr Attikou’s pupils got 10 out of 10 in the spelling test. It was a great success and never had Mr Attikou’s class been so joyful.

This way to carry out the exercise allowed Mr Attikou to give a good grade to all pupils in class even to those who were weaker in spelling, while putting them all to work, in a relaxed atmosphere. It is important that all children are winners occasionally. This helps them to build their confidence in their ability and motivates them to strive to do better. A while later, Mr Attikou gave the same test to the whole class and the weaker pupils did better.

![]() Collect your ideas:

Collect your ideas:

Consider changing the usual way in which you present class activities in order to have all pupils experience success once in a while.

Write down your ideas on a sheet of paper and add them to your lesson plans.

2.7 An inclusive teacher contributes to the emotional well-being of all children

Contributing to the child’s emotional well-being goes well beyond the school environment.

Activity 8: Nothing impossible

Activity 8: Nothing impossible

This activity will give teachers ideas on how to restore pupils’ self-confidence.

- Download the resource Seeking Help from the section Equal opportunities in the Audio resources area on the TESSA website.

- Listen to this short play and note how the teacher, Florence, helps Mimi overcome her lack of self-confidence caused by the negative attitude of her father at home. What precisely does Florence do to restore confidence in the young girl?

- Imagine the consequences of this ‘reinforcement’. Write the conclusion of the story.

You will have noticed that the teacher stopped the children’s teasing by sending them on break and that she kept Mimi behind to talk to her quietly. She interviewed her kindly to find something that she knows and likes to do and which would enable her to succeed in front of her peers. She provided support by giving Mimi time to rehearse her song. She also provided support by protecting Mimi when the rest of the class became restless when they heard Mimi was going to perform. What were the end results? Mimi found something she could do well, allowing her to win the respect of her classmates. The rest of the class discovered that Mimi could take on a challenge, succeed and shine in certain activities

Activity 9: The role of social environment on the pupils

This activity will enable teachers to reflect on the role of the children’s families and the social environment on their self-esteem and confidence.

- Think about your own experience. Can you remember how your parents’ attitude caused you to lose or strengthen your self-confidence?

- Can you detect children in your classes who have lost their self-confidence? Think about different means to rebuild that confidence.

- How could you open a dialog with parents to talk about their children’s difficulties and how they could support their children to help them at school?

- Can the TESSA resources you have used help you in this task?

2.8 Reflection on the inclusive teacher

According to Thacker (Opp-Beckman, & Klinghammer, 2006, p. 71) there are twelve attitudes a good teacher shows that help promote an environment conducive to learning.

Teacher behaviours for fostering a climate conducive to the development of thinking skills:

- Setting ground rules well in advance

- Providing well-planned activities

- Showing respect for each pupil

- Providing non-threatening activities

- Being flexible

- Accepting individual differences

- Exhibiting a positive attitude

- Modelling thinking skills

- Acknowledging every response

- Allowing pupils to be active participants

- Creating experiences that will ensure success at least part of the time for each pupil

- Using a wide variety of teaching modalities

Activity 10: Twelve attitudes of the inclusive teacher

This activity will help teachers to focus on and evaluate their vision of the inclusive teacher.

Annotate the above list of the 12 Teacher behaviours for fostering a climate conducive to the development of thinking skills.

- First, highlight the attitudes that have been discussed in this chapter of the toolkit. Annotate them by writing in the margin the main points you would like to highlight.

- Look back through the chapter to check your list against those discussed.

- Complete this list as you work through other chapters of this toolkit and find further illustrations of attitudes listed by Thacker. If necessary, come back to this page and continue annotating the list.

3. A classroom for all in a school for all

At the end of this chapter, teachers should be able to:

- organise the physical space in their classroom to create a safe environment

- take into account the situation of children with special needs to facilitate their access to learning

- reflect on the management of interactions within the classroom so that everyone can feel confident

- consider carefully the organisation of pupils to encourage collaborative learning

- understand the importance of motivation for positive schooling.

The organisation of the physical space and the atmosphere in the classroom/school play a crucial role in facilitating learning. To create a classroom/school safe from physical or emotional danger you, as a teacher, need to ask yourself the following questions:

- Do my school and class enable children to move without danger?

- What are the actions I can take to enable all children to enjoy an accessible and risk-free environment?

3.1 The physical space in the classroom and school

Case study 3: Mrs Dalok’s school board meeting

Mrs Dalok is the headteacher of a state primary school at Adétikopé in Togo. This school year, the school is welcoming children with disabilities: a child in a wheelchair who also has a lack of visual acuity and a child with a hearing impairment. The headteacher checks her school with her team of five teachers to establish what needs to be modified. The first item on the agenda is:

1. Adapting the physical space within the school and the classroom

Mrs Dalok: We will walk around our school to plan the modifications needed to welcome the two children with disabilities who are going to join us. Let’s first think about the infrastructure in our institution. What do you think we should adapt in the infrastructures?

Mr Eglo: I believe that we can work with pupils to level the ground within the school to allow the child to move freely in the wheelchair.

Ms Karim: Why should other pupils do the work?

Mr Touglo: It is a way to involve others and to show them that they can contribute to the successful integration of their new peer.

Ms Karim: Ah! OK! We must also think about what we need to do in the class.

Mrs Laban: I believe that the door to the classroom is too narrow for the child to enter with his wheelchair.

Mrs Dalok: We will take the necessary measures and call the builder to make the door bigger.

Mr Adji: We should also think about ramps. We should make a ramp from the door to the class and even from the class to the toilet.

Mrs Laban: I also think that the toilets are not adapted for the child’s needs and he will not be able to use them. Additionally, the class is not light enough. We could change the colour of the walls and blackboard to help the child with a visual disability. We could paint the walls into blue and white, change a section of the roof into a translucent pane to lighten up the classroom. We could also paint the blackboard in green and use yellow chalk, which will be more visible than white chalk on a black board.

Mrs Dalok: To conclude, first, call the builders to make the ramps. We have to avoid having steep ramps that could be dangerous not only for the disabled child but also for all children. Second, we will have adequate toilets put in and take measures to lighten the classroom. With the help of other pupils we can level the ground of the school.

This case study provides many examples of actions that could be taken to allow access to the premises and equipment to all children. Mrs Dalok, the headteacher, often mentioned how the new improvements for the children with disabilities will benefit not only them, but all pupils.

Activity 11: Promoting access for all children

![]() This activity will allow teachers to start exploring strategies to make the classroom more accessible to all children.

This activity will allow teachers to start exploring strategies to make the classroom more accessible to all children.

- Create a table similar to the one below.

- Read the case study again and note your findings and reflections.

- Add additional modifications about the physical space that you think about. If you are working in a group, organise a brainstorm (See TESSA key resource ‘Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas’ on the TESSA website).

| Modifications in the classroom or school – physical space | Benefits | Alternative or additional modifications |

| Level the ground of the school yard |

| |

| Etc. |

|

|

If you work with one or many colleagues, compare and share your answers and ideas. Discuss the things that would be possible in your school. You can return to this list as you work through other parts of the toolkit.

3.2 Answering the specific needs of the pupils

Case study 4: Mrs Dalok’s school board meeting (Part 2)

Mrs Dalok is the headteacher of a state primary school at Adétikopé in Togo. This school year, the school is welcoming children with disabilities: a child in a wheelchair who also has a lack of visual acuity and a child with a hearing impairment. The headteacher checks her school with her team of five teachers to establish what needs to be modified. The second point on Mrs Dalok’s agenda is:

2. Welcoming pupils with specific needs

Mrs Dalok: Mrs Laban, this child will be in your classroom. Have you thought about what you could do for him? Remember he has also an impaired vision so he cannot see properly. Everyone can give their ideas to help Mrs Laban to integrate this pupil successfully into the classroom.

Mrs Laban: I was thinking of placing him in a position where he can see the blackboard better and I will make sure that he can move around in class without being injured.

Mr Adji: We should also write clearly and bigger; read aloud what is written on the blackboard and prepare all the materials accordingly: big print, enlarged pictures, and so forth.

Mrs Dalok: Thank you everyone for your ideas. The other pupils can also help. There is a lot to do but remember that creating an environment more accessible for children with disabilities will be also beneficial for all pupils. They will all enjoy a more comfortable environment that will be easier to use. Now let’s consider the pupil with a hearing impairment. Mr Adji, how will you facilitate her integration into your classroom, as she will be joining your class? Everyone else is welcome to contribute, of course!

Mr Adji: First I would explain to the class the difficulties she encounters and the precautions we should take when we are talking to her. In the class, I will ask her to sit where she has her back to the light, not far from the blackboard and in such a way that she can see my face and the other pupils’ faces. When we talk in the class, we’ll have to articulate clearly and at a slower pace. I also intend to place her near a good, friendly pupil who will help her if needed.

Activity 12: Meeting the needs of pupils with specific needs

This activity will allow teachers to establish a list of strategies to make classrooms more accessible to different categories of children with specific needs.

- If you wish, copy the table below and fill it in as you read or use the headings to guide you when you take notes.

- Read the case study again and note down your findings and reflections.

- Add further physical modifications that you can think of. If you are working in a group, organise a brainstorm (See TESSA key resource ‘Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas’ on the TESSA website)

| Cause of disability | Actions | Reasons for action |

| Visual impairment |

| Better chance to access the information on the blackboard |

| Etc. |

|

If you are working with one or several colleagues, compare and share your answers and ideas and discuss the things that would be possible in your school. You can return to this list as you work through the other parts of the toolkit.

3.3 Managing classroom interactions to create a positive, respectful and accepting environment.

Teachers’ behaviours and their classroom management contribute to creating a calm environment that promotes learning. With their behaviours, teachers can model behaviours and attitudes that promote inclusion, and encourage pupils to adopt such behaviours.

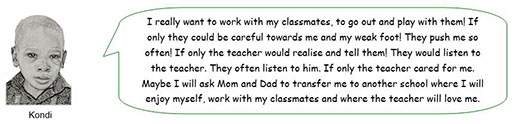

Activity 13: When the behaviours of pupils promote inclusion

This activity will allow the teacher to reflect on the impact of pupils’ behaviours in creating an inclusive environment.

- What is Kondi complaining about, his peers’ meanness or his teacher’s lack of awareness?

- What kind of behaviour can the teacher adopt to help Kondi?

- In addition to the teacher’s behaviour, think about other conditions that could be put in place to create a calm atmosphere that promotes learning.

- Kondi mentions that his classmates push him while playing. As a teacher, how could you help the pupils to adopt inclusive behaviours and attitudes?

- Read Section 3 of Module 2 of ‘Life Skills (Primary)’ on the TESSA website. What ideas do Mrs Aber and Ms Okon give? Add them to your list.

If you are working with one or several colleagues, compare and share your answers and ideas, and discuss the things that could be possible in your school.

All pupils need their teachers to show that they really care for them. When the teacher makes a conscious effort to know each pupil, it encourages him or her to do better, to integrate better and to participate more in class.

To establish a peaceful, safe and comfortable environment, teachers have to be proactive. For example, if teachers notice displays of aggressive behaviours by pupils, they may address these by using games and activities that develop empathy and encourage good social behaviours. The class will then be able formalise a shared and agreed set of internal rules.

3.4 Encouraging collaboration

Encouraging collaboration by giving each pupil a significant role matching his/her strengths and weaknesses

One way to integrate all pupils in the teaching/learning process is to encourage collaboration within clearly defined criteria set by the teacher. Working in a small group, pupils develop their social skills, learn from each other, share knowledge and encourage each other. Giving a significant role to each group member allows members of the group to mutualise their skills and diversities and respect each other’s differences.

Case study 5: Mr Sy organises group work

Mr Sy teaches at a school in Saint-Louis in Senegal. One of his favourite TESSA resources is the key resources Using group work in your classroom, which is on the TESSA website. He often reads it again when he wants to organise group work. To help his pupils, he prepared a poster.

Mr Sy: Children, we are going to work in groups of six.

The children: (all shouting and getting in groups of six) Yes, yes, yes sir.

Jean: I am the leader of the group.

Mr Sy: You were the leader yesterday. What about being the rapporteur today. Who will be the leader?

Ibrahima: Me, sir, me!

Mr Sy:No, we will ask Alice.

Jean: Oh! No! Not a girl!

Alice: Yes, sir!

Mr Sy: That’s good! Ibrahima, do you want to be the reader?

Ibrahima: Yes, sir!

Daouda: Can I be the time keeper?

Mr Sy: Very good, thank you Daouda. Djibril, what about you? What are you going to do?

Djibril: I do not want to be the summariser; I am no good at summary.

Mr Sy: I will help you. Okay, Djibril?

Djibril: Okay.

Abdoulaye: I’m going to be the artist.

Mr Sy: Okay. Are the other groups ready? Everyone has a role?

The children: Yes, sir.

Mr Sy: Good! Readers, come and collect the work to be done. I will go from group to group to help.

Activity 14: Good inclusive classroom practices

This activity will help teachers to identify inclusive classroom practices.

- Read Case study 5 again and identify good practices used by Mr Sy.

- How are these practices beneficial to each pupil?

- Download the key resource Using group work in your classroom from the TESSA website and add to your list of good practices.

If you work with one or several colleagues, share your answers and add to your list.

3.5 Focusing motivation to include all pupils in learning

If Kondi goes to another school and his new teacher is not an inclusive teacher, this will not serve any purpose. Indeed, if the teacher does not know how to respond to learner diversity by creating a positive classroom atmosphere and adopting a pupil-centred approach that facilitate learning and the integration of all learners, then Kondi will feel demotivated, and may increase the number of pupils who drop out of school.

Amotivation is what leads to the lack of motivation (Deci and Ryan, 2000). At this point, Kondi will not find any reason to stay in school or to persist in learning activities.

You must also be aware of the injustice that you could display against pupils when you do not have an inclusive attitude in your class. Your positive attitude towards all learners including those with disabilities and those with special educational needs should be obvious, as should your efforts to include all learners in the teaching–learning process. This can only be done if you take steps to create a positive climate in the classroom.

A positive climate is important for all pupils’ learning. This is aided not only by the mutual respect among pupils and between the pupils and you (the teacher), but also by the fact that you as a teacher have high expectations from all learners (in terms of behaviour, results, participation, etc.). You encourage them (TE4I, 2012) to meet your expectations by your warm and engaging attitude and you strive to make the class enjoyable both by its physical appearance and by the amicable atmosphere that stimulates learning.

Activity 15: Creating a positive atmosphere in your classroom

This activity will enable teachers to reflect on the impact of all pupils’ behaviours in fostering everybody’s inclusion.

- On which of the points mentioned above have you already worked? Section 3 of Module 2 of ‘Life Skills (Primary)’ available on the TESSA website and its associated resources provide examples of how colleagues proceeded to create a positive climate in the classroom.

- In Case study 2 of Section 5 of Module 1of ‘Life Skills (Primary)’ available on the TESSA website, the teacher, Mr Adamptey,targeted activities for his pupils to do to create a positive atmosphere. Read this case study and see what other activities you could add in your own situation.

- Complete Activity 2 in this section, Identifying your pupils’ personalities In the same section, read the third part, Celebrating success, (including Case study 3 and the key activity). Work with a colleague and consider how these activities help you promote a positive environment in the classroom. What else could you do to get to know your pupils better and help them to contribute to creating a positive classroom environment?

Activity 16: Twelve Attitudes of the inclusive teacher

This activity will allow teachers to reflect on their vision of the inclusive teacher.

- Read the instructions of Activity 10

- If you have not yet worked on this activity, follow the instructions and apply them to this chapter. If you have already started Activity 10, continue to annotate the list using what you have learned in this chapter.

4. Using language accessible to all

At the end of this chapter you will have guided the teachers in training to:

- identify the characteristics of a language accessible to all

- use strategies to ensure that all pupils understand

- develop support strategies to enhance all pupils’ understanding

- discover support strategies for technical vocabulary acquisition

- consider the use of the mother tongue to support learning.

Inclusive education means that the education provided is accessible to all. This is not limited to access to a physical space as is generally believed. It is often the case that another barrier to learning for some children is the language used. Not understanding what is being said is a cause of exclusion in the learning process. In this chapter we will examine different ways to ensure that the language used in class is understandable by all and accessible to all.

4.1 Accessible language: lexicon, syntax, diction, and elocution

Activity 17: Walking encyclopaedia

Activity 17: Walking encyclopaedia

This activity will enable teachers to identify the characteristics of a language that excludes pupils.

- Download the resource Walking encyclopaedia from the section Using appropriate language in the Audio resources area on the TESSA website.

- Listen to this short play and list all the examples of actions that should be avoided that could explain why Ibrahim is finding it so hard to understand Mr Jude. Draw some conclusions: what should teachers do to ensure that pupils understand them?

- What other aspects of language should a teacher consider to ensure that it is accessible to all pupils in the class? Add other ideas that would facilitate pupil understanding to your existing list.

- If you work with colleagues, compare your lists and discuss the strategies you could adopt to ensure that your own language is accessible.

A vocabulary and/or syntax that are inappropriate for the child’s age and experience can only create a barrier between the child and learning and between the child and the teacher. Teachers must choose their vocabulary and syntax they use carefully so that pupils understand them. Furthermore, teachers must have a clear elocution and diction and use their voice so as to maintain pupils’ attention. They must also ensure that children who need to lip-read will be able to do so easily.

4.2 Ensuring understanding in general

However carefully they choose their language, sometimes, teachers (and adults in general) use words that are not part of children’s vocabulary, which makes it difficult for pupils to understand instructions.

Thus, while preparing class lessons, it is important to think carefully about how to formulate and give class instructions.

Case study 6: Ms Touré’s instructions

In Segou (Mali), Ms Touré realised that several children in her second-year class always seem to start the work well after the rest of the class even though she gives them the instructions again and individually. She believes that this limits the length of time available to perform the required tasks and that this affects their results.

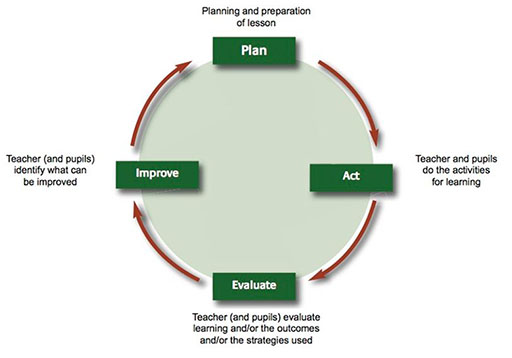

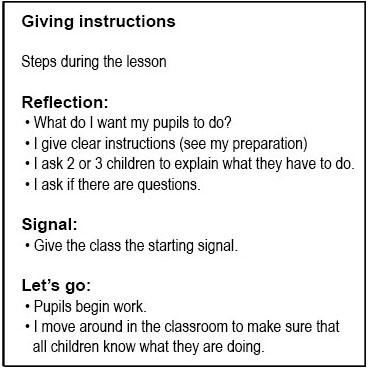

She asks a colleague to come and observe and to pay particularly attention to the way she gives instructions. After the observation, during the feedback, they agree that the instructions were given in a confusing and hasty way. Therefore, they decide to adopt a new course of action: when she prepares her lessons, Ms Touré will use the prompt card they devise together on how to give instructions. She will also use this card as a reminder in the classroom.

Ms Touré believes that although it will be time consuming, writing the instructions when she does her lesson preparation will allow her to be more precise and clearer in the classroom. She thinks that asking children to repeat the instructions is a useful technique: they will use their own words to explain things and thus will facilitate the understanding of instructions for all pupils. This will allow her, Ms Touré, to check for their understanding.

4.3 Actions speak louder than words

Mme Touré’s method is one way to ensure children’s understanding. There are many others.

Activity 18: Strategies to help children understand explanations

![]() This activity will allow teachers to start building a bank of ideas they will be able to use to support pupil understanding.

This activity will allow teachers to start building a bank of ideas they will be able to use to support pupil understanding.

- Download from the TESSA website and read the TESSA key resource ‘Using explaining and demonstrating to assist learning’

- Read and annotate both sections titled ‘Assisting learning by demonstrating’ and ‘Explaining is not one-way’.

- Using a table like the one below:

- Write some ideas of how you can use demonstrations and explanations in the ‘Strategies’ column.

- Now think about your pupils who need much more support and, in the ‘Adaptations for certain pupils’ column, write down your ideas to facilitate understanding for these pupils.

| Strategies | Adaptations for certain pupils | |

| 1 | Illustrate the explanations with images, diagrams, objects … | Serge (visual impairment): large images Emilie (blind): An object that can be explored through touch |

| 2 |

| |

| Etc. |

|

4.4 Use of technical vocabulary

When you address children, it is important to use words and structures that are easily accessible to them, regardless of their ability level. However, in all disciplines, you will need to use technical words: a fault line in geography, osmosis in science, a bisecting line in mathematics to name a few. All these technical terms will be new words for pupils, words that they will need to understand, learn and memorise.

Activity 19: Strategies to help children understand and memorise technical terms

This activity will enable teachers to consider techniques that help children understand and memorise technical terms.

- Brainstorm and list all the strategies you can think of that will help pupils understand and memorise technical terms. (See TESSA key resource ‘Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas’ on the TESSA website.)

- Then read the Case study 2, Activity 2 and Resource 2 of Section 1 of Module 2 of Numeracy (Primary) on the TESSA website. If necessary, add ideas to your list.

If possible share and compare your ideas with a colleague.

In addition to using a dictionary, what is on your list?

- Posters on the walls of the classroom with the new words to be learned and practised, and illustrations explaining them

- Signs placed on walls with new words and definitions

- Activities for learners to practise using these new words, such as games and puzzles.

4.5 Use of one’s mother tongue

The appropriate use of the mother tongue can help teachers to evaluate the knowledge and understanding children bring with them and help them to learn further, as illustrated in the following case study.

Case study 7: Mr Auckbar uses the Creole language in his Form I class

Mr Auckbar wants to teach relative position of objects to his class in a primary school in Port Louis, Mauritius. He knows that, in Creole, the concepts of left/right, over/under, top/bottom, front/back, that can be translated asgoss/drawr, lor/en ba, la o/en ba, divan/derrier, are particularly difficult for his young pupils. He knows the importance of using English in his class, but he also knows the value of a multilingual approach and he is sure that at home his pupils will have heard these words when their parents ask them to store various objects. He decides to check and enhance their understanding of these concepts in Creole before resuming in English.

During researching the TESSA resources, and particularly in Section 1 of Module 3 on Literacy ‘How can you help pupils to practise language structures in a natural context?’, Mr Auckbar noticed some useful strategies. Using examples of activities based in games, he was able to help pupils develop an example of these concepts. The children took great pleasure to build scaffoldings with their rulers, pencils, erasers and pens, following the instructions given by Mr Auckbar in Creole then in English; first slowly and then faster and faster when the children had gained confidence and showed that they understood the concepts. Finally, Mr Auckbar and the pupils were really happy when some of the children could give the instructions in English and made sure that their friends had placed the objects correctly.

With continuous use of the TESSA resources, Mr Auckbar found other examples and case studies in Section 4 of Module 3 on Literacy: ‘How to benefit from the knowledge of a local language?’. He decided to keep them at hand to reinforce the main constructs in relative position of objects throughout the class session.

5. Planning and preparing lessons to include all pupils

At the end of this chapter you will be able to…

- set out clear and achievable objectives for the inclusion of all

- break down the objectives and the lesson plan into progressive and feasible steps to facilitate progress and learning

- use activities providing different sensory approaches and outcomes

- select, develop and use a wide range of resources to meet the various needs of all

- understand the meaning of differentiated pedagogy and which elements of the preparation and the lesson can be tailored to meet the needs of all pupils.

Lesson planning is a crucial activity to prepare for the inclusion of all children in the teaching–learning process. It is during the lesson planning that teachers lay the foundation for allowing everyone to have access to the necessary skills, knowledge and know-how. It will also facilitate opportunities for participative learning and classroom life. Everyone will have the chance to progress and succeed. It’s during that time that teachers will reflect on the means required to provide support to everyone.

Activity 20: Lesson planning form

This activity will allow teachers to start developing a tool that will support them on planning inclusive lessons.

- Download the key resource ‘Planning and preparing your lessons’ from the TESSA website.

- Read it, list the points that are important to you and create a lesson planning sheet that will help you prepare daily.

If possible, share and compare your ideas with a colleague.

Save the form that you create: you will need it in Activity 28, which you will do at the end of the chapter.

5.1 Differentiated goals

After reading the section Planning lessons of the TESSA key resource ‘Planning and preparing your lessons’, you have noticed the importance of objectives that:

- reflect what the teacher intends the pupils to learn, at this and different levels

- encompass different elements (understanding, knowledge, competency, skills)

- can be measured through the learning outcomes.

The relationship between objectives and outcomes is illustrated in this table:

| The objectives express that at the end of the lesson, the teacher expects the pupils to … | Examples: At the end of the lesson, pupils will | Learning outcomes: How to evaluate whether the objectives have been achieved? |

understand (Understanding) or | demonstrate how and why meandering rivers are formed. | How will the understanding of meanders be measured? |

know (Knowledge) or | be able to draw and name the parts of a flower. | How to evaluate what children know about plants? |

| do (Skill/Know-how) | have made a clay pot. | Are the pots ready? |

It is important to add another two characteristics of learning objectives.

a.The objectives have to be achievable by all the pupils at different levels. In fact, if the objectives are not achieved, the pupils will be failing, and therefore feel frustrated because they cannot meet the expectations. This may demotivate them and they turn them off school.

b.The learning objectives (and the learning outcomes) must be differentiated in such a way so as to take into consideration and value all pupils’ talents and needs. One way of differentiating the objectives is by defining what:

- all pupils will understand/know/be able to do

- most pupils will understand/know/be able to do

- a few pupils will understand/know/be able to do.

For example

- All the pupils will have made a pot.

- Most of the pupils will do a pot with straight and waterproof sides.

- Some pupils could do a pot with straight and waterproof sides, with decorations and a handle.

5.2 Learning through small steps

You may have noticed while reading the section ‘Lesson planning’ of the TESSA key resource ‘Planning and preparing your lessons’, that It is important to break down subjects and topics to be dealt with in lessons into sections that can fit into a lesson time.

It often occurs that the portion of the subject or theme selected for one lesson is complex, because it is composed of several elements, or because it asks for new competencies or knowledge, but also because children acquire new competencies or knowledge in differently sized bites. Therefore, it is necessary to break down their teaching–learning into small steps that are well articulated and logically organised. This will allow all pupils to attain the objectives of the lesson.

Activity 21: One step at a time

This activity will provide teachers with examples of the steps in planning lessons.

- Download from the TESSA website Section 4 of Module 3 of Life Skills (Primary) and read Case study 1.

- While reading the case study, make notes on: 1) The objectives of the activity proposed by the teacher 2) The different activities/steps that the pupils will go through to reach the objective.

You should also consider one or more activities that will enable you to evaluate whether the pupils have learned, what and how much they have learned. For more information, please consult the chapter ‘Assessment and feedback’ in this toolkit .

5.3 A directory of activities

After deciding upon the lesson’s objectives and all the elements to include, it is time to consider the activities that will best allow pupils to take part in the learning process and achieve these objectives. The activities concerned are activities pupils will do in the lessons and that will engage their mind actively. (See About TESSA in the Teaching Practice Supervisor’s Toolkit.

It is important to remember that we all have different and preferred ways of learning:

- Some of us, the ‘visual learners’, learn by visualising the information. Sight is their sense of predilection. For them, a picture or a diagram speaks louder than words. They love to explain while drawing or designing models.

- Some of us, the auditory learners, learn by listening. Hearing is their predominant sense. They love words, music and oral communication. They may take very few notes and often choose to remember things by putting them in rhymes or music.

- And finally, some of us, the kinaesthetic learners, learn by moving, touching or doing. They prefer to experiment rather than just follow instructions.

Howard Gardner, a developmental psychologist, defines nine types of intelligence that give different access to learning. This theory, although now controversial, allows us to take into consideration the differences and the needs of individuals when we prepare lessons.

a. Activities for all senses and all types of intelligence and to support the development of a range of skills

In your class, you have children with different learning styles. You may also have children with disabilities and you will need to select activities that will allow them to learn. Pupils with visual impairments are likely to respond well to auditory activities. Those that are hyperactive will have done well in activities for kinaesthetic learners that will enable them to move, and finally the techniques adapted for visual learning will be useful for deaf or partially hearing pupils. Thus, when preparing lessons, it is crucial to plan a range of learning activities that will cover the needs of different learners by catering for the range of learning styles.

By selecting a varied range of learning activities, not only will you take into consideration your pupils’ different learning styles, but you will also ensure that pupils develop a wide range of competencies.

Case study 8: Teachers adapt activities to meet some of their pupils’ needs

8a: Mr Sadio adapts a science lesson for Hadiatou

For his science lesson with the CE2 class in a primary school of Kankan in Guinea, Mr Sadio has decided to use a sorting exercise as used by Ms Ukwuin Case study 1, Section 1 of Module 1.

He read the case study carefully and prepared his lesson plan making sure that all steps were well defined and that all the resources he would need were available. Then, as usual, he thought of ways he would adapt the activity to enable Hadiatou to participate and learn. Hadiatou is blind and is always ready to try new activities. For this activity, he will check that she can manipulate selected objects easily and safely (for her and the objects). Then, he will make her work in pairs with Souaré. Souaré is patient, attentive, and he talks clearly. Before the lesson, Mr Sadio will talk with Souaré and tell him exactly what he expects from him when working with Hadiatou: he will have to guide her towards the tables, describe what is in the tables to her. Then he will accompany her to the yard and pass objects to her so that she can choose two or three objects. When the children will get back to the classroom with their non-living objects, each child will have to describe clearly what he has chosen and why, and to indicate where he will place his objects and why. When it comes to drawing a plant or an animal, Hadiatou will tell Mr Sadio what she wants to present to the class and he will draw it quickly himself so that Souaré will be able to do his own work. Finally, every object will be described in such a way that Hadiatou can take part in the discussion.

8b: The day Gilou got 10 out of 10 in arithmetic. His mother tells the story:

‘That day, Gilou came back from his school in Tsévié, Togo. He was proudly holding his slate. On it were red markings: very good 10 out of 10.

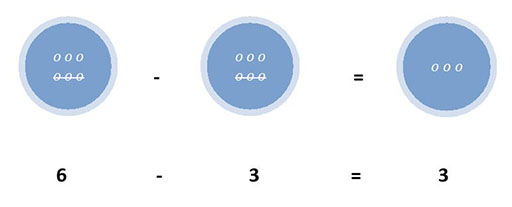

He proudly told me: “Mom I did my sums right! Look! I’ve got 10 out of 10.” I took his slate and looked: it had three circles, the first one with six pebbles of which three were crossed off, the second and the third ones contained three pebbles each. In between the first and the second circle there was the minus sign and the equal sign was between the second and the third circle.’

What had the teacher done for Gilou? Knowing that Gilou found it difficult to set out and resolve sums, he had used a diagram to set the sum while the rest of the class calculated it more traditionally. By using differentiation by task, the teacher enabled Gilou to give a correct answer, thus allowing Gilou to obtain a perfect score like the others. During a later session the teacher helped Gilou to put the number in the boxes:

8c: Mr Sarré, a teacher in Senegal, talks about the spelling test he is preparing for Antoinette

In general, when we do a spelling test and there are children with hearing loss in the class, we must go slowly and we face the pupils. However, Antoinette is profoundly deaf, so I am going to prepare the dictation text with mistakes in and will ask her to identify them while her friends will write the actual text.

8d: Talented children have special needs too

Bintou is a pupil in a state school in Bamako, Mali. She is in Mrs Samaké’s grade 4 class. Bintou works quickly and often finishes the classwork before her friends. At the beginning of the school year, she showed a great sense of curiosity and asked many questions that revealed that she has an excellent memory and quickly identifies abstract relations linking topics from different school subjects. But in recent weeks, Bintou does not participate as readily in class activities and often seems bored. Concerned that this disengagement has a detrimental effect on Bintou’s progress and achievement, Mrs Samaké discusses Bintou’s case with the school counsellor (SC) who asks many questions about the child. He thinks that Bintou is probably a talented child who needs to be motivated. He advises Mrs Samaké to continue using the active learning approach she uses and to engage Bintou by avoiding, for example, to give her repetitive exercises to do. The SC suggests that Mrs Samaké starts creating a bank of graded exercises with answer cards for self-checking and self-assessment. It will allow Bintou (and others) to work at their own pace and at their own level, independently or in groups. He also recommends the use of exercises for Bintou to do research work, to solve problems, and to use her curiosity and creativity. For example, after completing two or three exercises, Bintou can invent similar problems and provide their solutions: this will prove she has understood and the problems created by her could be used for the bank of graded exercises for the class. Furthermore, Bintou could engage in activities allowing her to satisfy her curiosity, such as taking advantage of a reading corner or a mathematics corner when she finishes the training exercises. In all the cases it is important to continue to include Bintou in the class: peer tutoring would enable Bintou and other more advanced pupils to tutor classmates. This could also be a way of meeting her needs.

Activity 22: Activities for all

For this activity, teachers will consider different learning activities and decide which type of activity is best suited for which type of learner.

- Gather the preparation notes of the last two lessons you have prepared.

- Draw a table like the one below, and do the following for each preparation sheet:

- In column 1, note down the activities done by the pupils.

- In column 2, specify for which kind of pupils these activities (visual, auditory or kinaesthetic) are appropriate and the skills that they will develop.

- Finally, in the last column, indicate for which pupils you would require personalising the proposed activity – think about their gender (girl/boy), disability, etc.

| Activity done by pupils | Learning type and skills being developed | Adjustments for … |

| Earth science: Classification of living and non-living objects (TESSA Sc M1 S1 EdC1) | Visual Observation, logic | Deaf children: Use sign language to give instructions or put them in writing in advance Blind children: Choose items that they can touch or make them work in pairs and have their partner give detailed descriptions (brief partners carefully) |

| Maths |

|

|

| Etc. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Reread your list critically. In each lesson, do you have activities that cater for different types of learners? If not, which activities could you introduce so that all types of learners reach the learning objectives?

If possible, share and discuss your ideas with a colleague.

b. Recreational activities

Learning is a very serious task, but as you may have noticed in several chapters of this toolkit, promoting a good atmosphere is conducive to learning (whereas fear hinders learning). Therefore, carefully planned games have their place among the repertoire of learning activities. They often help pupils to learn without effort and help teachers to observe pupils, their understanding of concepts, and their strengths and weaknesses.

Activity 23: Games to learn

This activity will allow teachers to discover several games and consider how they contribute to learning in various school subjects.

- Download the following resources from the TESSA website:

- Literacy (Primary), Module 2, Section 3

- Literacy (Primary), Module 3, Section 1

- Numeracy (Primary), Module 1, Section 1

- Sciences (Primary), Module 3, Section 1, Resource 2

- Social Studies and the Arts (Primary), Module 1, Section 1

- Life Skills (Primary), Module 1, Section 2.

- For each of these examples, make a note of the game being used and the learning objective(s) reached through play and a relaxed atmosphere.

- If you have other ideas for learning through play, add them to your list.

If possible, share and discuss your ideas with colleagues.

c. Varied and open ways to present the results and outcomes of an activity

Teachers often ask children to present the results or outcomes of activities performed in class or as homework as a piece of writing. However, to stimulate pupils’ interest and develop different skills, alternatives should be considered. It is also recommended to sometimes give pupils, the opportunity to choose how they will present their work.

Activity 24: Activities with varied results

This activity will show teachers in training how creative teachers assign activities that lead to original results/outcomes.

- Download the following resources from the TESSA website:

- Science (Primary), Module 1, Section 4

- Literacy (Primary), Module 1, Section 5, Case study 1

- Numeracy (Primary), Module 3, Section 5, Case study 2 and 3

- For each one of these examples, note the activity and results/outcomes. Also write down your opinions about what was offered by the teachers to the pupils.

- Alone or with colleagues, brainstorm ideas of activities and the way they impact the learning experience. (See TESSA key resource ‘Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas’ on the TESSA website).

TESSA resources contain many examples of activities that lead to diverse results/products: a drawing, a poster, a sketch, a dance, a play, a debate, a presentation, or, as in the case studies that you have just read, real outcomes useful for the school and the community.

5.4 Resources for all

The teacher must prepare their lessons that stimulate all the pupils’ interests. One aspect of the preparation is to identify resources that will assist or encourage the pupils to learn.

a. Where to get resources

It is not always easy to find the resources you need. You will often have to be a resourceful, creative and inventive teacher.

Activity 25: Appropriate resources

During this activity, teachers will identify appropriate resources.

- Download and read the following key resources from the TESSA website:

- As you read these documents, highlight the ideas listed in them that you can easily reuse in your class. If these ideas trigger new ones, write them down in the margin.

![]() If you are working with groups of teachers, share, discuss and develop these ideas. During your work with TESSA resources, make notes of how useful these resources/ideas that you have put into practice were and how you could improve them.

If you are working with groups of teachers, share, discuss and develop these ideas. During your work with TESSA resources, make notes of how useful these resources/ideas that you have put into practice were and how you could improve them.

TESSA resources offer many examples of teacher ingenuity in terms of finding resources: a list of objects is drawn for the making of musical instruments in Resource 2, Section 4, Module 3 of Social Sciences and the Arts (Primary) or, in the same module, old tools traditionally used in agriculture brought by a member of the community (Case study 2 of Section 2). The teacher cannot do without this invaluable support. It may even be the case that some community members are happy to share resources for the classroom and for the school.

b. Choosing or developing learning resources

When selecting and preparing learning resources, whether they are especially tailored or collected from the classroom, school or community, teachers should analyse them from different perspectives.

Selected or made-up resources must meet everyone’s needs. If in a class, there are one or more children with disabilities, do these resources enable all of the children to learn? Are they multi-sensory so that everyone may benefit from them? If these children are blind, will they be able to touch, smell and listen? If they are deaf, will they be able to visualise the information, smell or feel? The stories in Case study 8 illustrate how teachers think carefully about resources that will be used to enable all children to be able to carry out the learning activity.

The selected resources convey a positive image of people belonging to minority groups

Activity 26: Selecting resources that convey a positive image of people in vulnerable minority groups

This activity helps to identify or create resources that enable a) pupils with disabilities to identify with the selected materials and b) pupils without disabilities to appreciate that everyone can contribute to one’s learning.

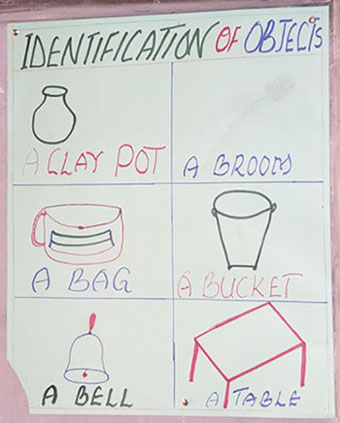

- Look at the illustrations of school subjects in the pictures above: how do they promote inclusion among pupils?

- Now download the following three TESSA resources from the TESSA website. Read them carefully and reflect on them. How could they be adapted in order to give a positive image of people with disabilities?

- Mr Simon Ramphele organises a session to read newspaper articles on famous people: Case study 2 of Section 4 of Module 2 of Literacy (Primary)

- Resource 3 of Section 4 of Module 2 of Literacy (Primary) on using praise poems

- Resource 4 of Section 4 of Module 2 of Literacy (Primary) on preparing to write a biography.

As you read and discuss ideas with colleagues, add to your own collection of ideas.

While allowing children with disabilities to have a positive image of themselves, the chosen resources convey the message to all children that everyone can access the same opportunities: boys learn home economics, girls do science experiments, children in wheelchairs play basketball, etc. To further enhance the image of minority groups, Mr Ramphelecould include a few articles about Paralympic athletes or fashion models wearing a prosthetic leg. In the discussion and preparation for writing the biography, why not choose a character representing a vulnerable group of the population?

c. A resource centre for the school or for several schools?

The same resources will be useful to many teachers in the same school. It would therefore be appropriate to catalogue these resources and share them within the school.

Case study 9: A group of student teachers create a resource centre

During her teaching practice, Aisha had to teach a sequence of lessons on weather forecasting. She remembered the work she had done using TESSA resources in her NTI* Distance Education modules. She researched Section 3 of Module 1 on Social Studies and the Arts (Primary), and decided to build a weather station for her class using the instructions from the Resource 3: ‘Measuring the wind direction and speed’. Her sequence of lessons was a great success for both the pupils and teachers of the school.

Back at the NTI Regional Centre in Kaduna, during a feedback session on the teaching practice, Aisha shared her success and experience. Inspired by her success, the other student teachers expressed the wish that she shares her resources with all of them, and also with teachers in the training schools.

The student teachers received permission from the Head of the Regional Centre for the creation of a mini resource centre located in a small room. They put in all their resources and shared them with the teachers of the local school.

* NTI: National Teachers' Institute, Kaduna, Nigeria

Following this example, one or two teachers could be responsible for collecting and managing learning resources in a school. This would allow teachers to share and integrate all their good ideas for the benefit of all children.

5.5 Differentiation

Differentiation is a process that involves the adaptation of teaching-learning strategies to the needs of all learners: ‘The purpose of education for all children is the same; the goals are the same. But the help that individual children need in progressing towards them will be different’ (Warnock Report, in Dickinson and Wright, 1993, p. 2). Differentiation is therefore a process whereby teachers recognise the individual pupils’ needs in their classroom, and plan accordingly to meet those needs, to give each pupil access to learning according to his/her own capability and to account for differences in comprehension, abilities, current knowledge and what he/she can achieve.

This process does not happen automatically: it has to be well planned. Differentiation means that the teacher(s) will do something intentionally. This is related to lesson planning to meet the individual needs of each learner. It is based on understanding individual differences, as well as the value placed on the learning of each pupil.

You should be aware that children acquire new knowledge, skills and understanding in different ways and at a different pace. The class lesson should be presented in such a way that the learner has access to the new teaching aids in order to progress.

Activity 27: Which aspects of the preparation and teaching can we adjust to ensure differentiation?

This activity will allow teachers to identify the components of lesson planning and teaching that contribute to differentiation.

- Read this chapter again quickly and make a list of the components of your lesson plan that can be modified to meet everyone’s needs.

- Next to each component that can be differentiated, indicate how they can be modified and how this will help meet the pupils’ needs.

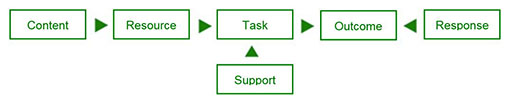

According to Dickinson and Wright (1993, p. 3), the teacher can differentiate in a number of ways. The diagram below considers the aspects of a lesson:

Generally, the content is set to meet National Curricula and cannot be modified. Differentiation by content is therefore not usually possible.

The outcomes are those produced by pupils, and thus are variable. Outcomes are not an aspect that can be differentiated by teachers when they plan and prepare the lessons. Differentiation by outcomes is not something teachers can control and plan for.