Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 11:20 PM

Module 2: Exploring social development

Section 1 : Exploring social networks

Key Focus Question: How can using role play, family trees and local experts help you explore social networks?

Keywords: role play; differences; problem solving; large classes, social networks; family trees

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- set up discussions and used family trees to identify pupils’ immediate and extended family;

- used role play and problem solving to explore school networks and relationships;

- worked with local experts to extend pupils’ knowledge about community networks.

Introduction

Children have different family, clan, ethnic and other social networks to which they belong and which define who they are. As a teacher, you need to be sensitive to these differences and work to make all your pupils feel included as they build more networks.

In this section, you will use a variety of teaching methods and resources to help your pupils identify their own networks and to respect their differences. We start with discussion and drawing family trees to find out about family relationships. You will use role play and problem-solving activities to help pupils identify their school network. Finally, we propose that you invite a local expert to explore the wider community networks that form part of your pupils’ lives.

1. Exploring family networks with large classes

We all have very different family networks but there are often many common elements and structures that we can compare.

When discussing family networks, some children in your class are likely to come from very different family set-ups from the others. You will need special skills to help and support these children cope with their differences and ensure that the other class members also respond positively to these differences.

Large classes present particular problems for teachers – especially if they are multigrade classes. Case Study 1 and Activity 1 make some suggestions for exploring family networks with different-sized classes and pupils in different grades.

The strategies used here are presentation, small group discussion and giving feedback.

Key Resource: Working with large classes and Key Resource: Working with multigrade classes give further ideas.

Case Study 1: Discussing family types with a large class

Miss Ndonga from Namibia has a class of 72 pupils. The class is working on social networks and she wants to use different methods to help her pupils identify family types. She knows it is important to help the children to discover things for themselves, rather than just telling them. She talks about family types and asks her pupils lots of questions about different family types. This tells her what they already know and keeps them interested. She notes that three girls sitting at the back never answer her questions and decides to talk to them at the end of the class. Together, the pupils identify different family groupings including nuclear and extended families, single-parent and child-headed family groups.

The pupils are sitting in desk groups of five and Miss Ndonga lets them stay there. Desk groups are not always the best grouping, but sometimes it is the only practical way, especially with very large classes. These groups are mixed age and mixed ability.

Each desk group discusses their own situations and identifies the different family groups they live in. The groups then feed back and Miss Ndonga lists the different family types on the chalkboard. The pupils copy the list into their notebooks. They do a survey with a show of hands to count the number of each different family type in their class. They have a class discussion about why it is important to respect differences in family types.

In the next lesson, Miss Ndonga asks the same desk groups to talk about why we live in family groups. The reasons they identify are shown in Resource 1: Reasons for living in families. The groups also talk about the types of houses they live in and what their houses are made of. Finally, they write a short essay on their own family and house and explain how it is different from that of another class member, usually a close friend.

Activity 1: Discussion and feedback on family networks

For this activity, you need to plan a lesson on exploring family networks. To do this, you need to consider the following:

- If you have older pupils or a large class, it would be appropriate to use the same discussion and feedback methods as Miss Ndonga. With younger pupils, you can still use group or whole-class discussion, but you may find drawing family trees will help young pupils to understand their family relationships better (see Resource 2: Family network).

- With younger pupils, you can also use drama, letting group members play the roles of the family members. It might be fun to find out who has the largest family in the class, or the family with the most females. You could link this to survey work in mathematics lessons.

- Be careful if you have child-headed households in your class, as these pupils may feel they are too different from the others and may feel ashamed or embarrassed. You will need to support these pupils and help them feel good about themselves. Make sure that other pupils do not react badly to the difference and make these pupils feel uncomfortable.

- How you will start the lesson to capture their interest? What activities do you want the pupils to do to achieve the learning outcomes of the lesson?

- When you are happy with your plan, carry out your lesson.

2. Using role plays and problem-solving

People, especially children, usually feel happy and secure when they are part of a group. This is particularly true outside the family. In school, for example, friendship groups are very important to children. Friendship groups are often a positive experience, but sometimes they can have a negative impact on individual children who are left out or picked on by others. In this part, you are going to use role play and problem solving to help your pupils explore their friendship groups and the influence these have on their daily lives.

You will need to spend some time preparing appropriate role plays for the age of the children in your class. Some suggestions are made for you in Resource 3: Role plays for exploring school networks. This will help you start, but you can probably think of other relevant and real situations that you can use. Think carefully about the individuals in your class, consider any problems that have arisen and be careful how you set up the role plays.

With younger pupils, it is important to help them build up good relationships and friendships so that they find coming to school a positive experience. Using stories about different situations that might arise is one way to stimulate ideas about to how to help each other.

Case Study 2 shows what happened when one teacher used role play and problem solving in her class.

Case Study 2: Friendship groups

Miss Musonda wanted to help her Grade 5 class discuss the impact of friendship groups. She first prepared some cards with appropriate problems for the age of her pupils. She spent some time thinking about different problems that her pupils, who were mostly 11 or 12 years old, may face. She knew this is a difficult age for many children as their bodies are starting to change physically and they start to have hormone surges. She also particularly wanted to tackle a difficult problem she was having with a group of girls who were constantly being nasty to one girl.

Over three lessons, Miss Musonda asked three groups to present role plays to show the problems she had identified on the cards. The class had some interesting discussions after each role play. Sometimes things got a little heated when pupils had different ideas about solving the problem, but Miss Musonda encouraged them to listen to each other and respect differences.

For homework, she asked the class to work in twos and threes to think of situations that they would like to role-play for the class to discuss. This was quite a high-risk activity, because Miss Musonda did not know what situations they would come up with – so she could not prepare herself. The role plays included bullying, being hungry and having no friends in school. Miss Musonda was pleased with their presentations and glad that there were no problems or surprises.

Activity 2: Problem solving in classroom networks

Friendship groups are not the only groups to which children belong in school. Here is a good way to identify different groups when you have a large class. This method involves all the children moving around the class at the same time, so you will need to establish the rules for this if you are to keep control. You may find a whistle is helpful.

Start by asking about the different groups that pupils belong to in school. Each child writes the name of one group they belong to on a piece of paper and pins it to their clothes at the front. On your signal, they move around the class and find another person in the same group. Give them three minutes. Look out for anyone who is not in a club or group or who cannot find a ‘pair’ and help. Then blow the whistle again and each pair must find another pair – again, give them three minutes. Keep going like this until all the groups are formed. Ask the pupils to count the groups and write them on the chalkboard to establish the group with the most/least members, the most girls/boys etc.

Ask the pupils to sit back at their desks. Then ask them to write down what they found out, using the information recorded on the chalkboard. You can have a discussion about which groups are the most popular and why. Or which groups have very few members. Perhaps the members of this group can make a short presentation to tell the class about their activity. You could encourage some to join a new group.

With younger pupils, you may want to work with one group at a time and spread the activity over a week, with you recording their ideas.

You can read about some examples of school clubs in Resource 4: Zambian school clubs.

3. Working with the community

Inviting people from the community into school can help keep pupils motivated to learn and make their lessons more exciting. Handled well, such activities can help you make life skills lessons very relevant for your pupils. This is a good way to introduce your pupils to some of the different networks in their community.

However, inviting experts into the classroom may take some time to arrange – you have to identify appropriate people, make arrangements with them and make sure they understand what you want them to do. You also have to prepare resources for your pupils so that real learning takes place.

Remember to assess what the pupils have learned after the event. Not only about the topic of the visitor, but also what they have learned about organising such an event. You can do this in different ways – there are some ideas in the Key Activity. See Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource to help you plan the visit.

Case Study 3: Community networks

Miss Nkamba talked about community networks with her Grade 6 class. In pairs, pupils talked about which different community groups they were members of, or which they knew about. They listed all the different groups on the chalkboard:

- Clan/ethnic group

- Religious group

- Boy scouts/girl guides

- Sports clubs

- Dance group

- Choir

- First Aid Club

After discussing how many pupils were members of each different group, the class voted to invite the local Muslim leader to come and talk to them. They did this because only one member of the class was a Muslim and the others wanted to know more about it.

First, Miss Nkamba went to the school library and found a book about different religions. She learned about the Islamic faith herself and prepared a lesson on the basic features of Islam. She did this so the class would have some knowledge on which to base what they learned from the visitor.

The pupils wrote short essays on the Islamic faith and Miss Nkamba put them all on a special table at the side of the classroom so that everyone could read them. She also asked her pupils to prepare questions they wanted to ask the visitor and they agreed which were the best questions and who would ask them.

When the visitor came, he was very interested to see the pupils’ work and find out what they already knew about the Islamic faith. He brought interesting artefacts for the children to see and the pupils were really interested in his answers and asked a lot more questions.

Miss Nkamba was really pleased with the way the visit had motivated her pupils and decided to follow it up with a visit to the Chibolya mosque. She also decided to invite Mr Patel of the Zambian Hindu Society to give a similar talk.

Key Activity: Using class visitors to motivate pupils to learn

Find out which community groups your pupils are members of. You can use the same method as Miss Nkamba, or brainstorm with the whole class or use small groups – it will depend on the size of your class and the age of your pupils.

Decide, as a class, which community group you would like to find out more about.

Prepare yourself – you may need to do some reading.

Introduce the subject to your pupils.

Discuss the tasks that have to be carried out (using Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource).

Help your pupils to prepare questions to ask the visitor.

Ask for volunteers (or pairs or groups) to carry out the different tasks.

Guide your pupils as they complete their tasks.

After the visit, remind the pupils responsible to write a letter of thanks.

Have a round-up lesson where you explore what the pupils have learned. This could be done in a variety of ways:

- for older pupils – discussion, writing stories, role play, a quiz;

- for younger pupils – drawing pictures, role play.

Resource 1: Reasons for living in families – Miss Ndonga’s class list

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

- To protect children.

- To provide food and shelter for children.

- To teach children how to live.

- To teach children the things they need to know, such as honesty and respect for others.

- Because children cannot support themselves.

- For adults to have companionship.

- Because people are social beings and cannot live alone.

- To provide a role model for children.

- To share friendship and love.

- To share the tasks.

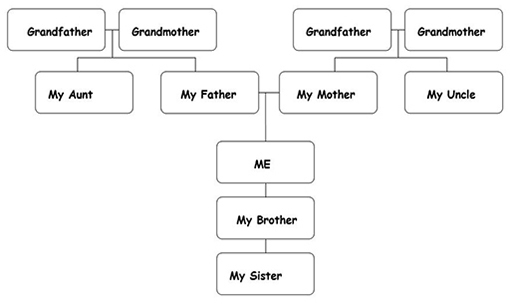

Resource 2: Family network

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Copy this tree onto the chalkboard or a poster. The children could copy it into their notebooks, or onto newsprint if you want to display their work.

Each child should first make a list of the people in their family that they want to include in their tree and draw the correct number of boxes. This could involve more or fewer boxes than are shown here.

Resource 3: Role plays for exploring school networks

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Here are some ideas to get you started when thinking about role plays. With a little thought, you will be able to build on these ideas and think of role plays suitable for your pupils. Remember to think of questions for the class, after the children have performed the role play. You will need to make sure they understand what they have to do and say. Also, make sure that everyone gets a chance at performing. You could also ask the pupils if they think the teacher should get involved in any of these problems.

Younger children

- Fellly and Precious have been friends since Grade 1. They are now in Grade 3. A new girl, called Beatrice, joins the class. Felly decides she will not be friends with Precious any more as she likes going to Beatrice’s house to play with her dog. Precious is very unhappy because Felly is unkind to her. She spends most break times crying.

- What could Precious do to solve her problem?

- What should Felly do if she really cares about Precious?

- What could Beatrice do to help the situation?

- Frank is a very shy boy. He wears heavy spectacles because he does not see very well. He does not like sports and is not very good at them. None of the boys in his class will be friends with him because he will not play football. He is often alone and hates school because he does not have a friend.

- What advice can you give Frank?

Older pupils

- Joseph wants to hang around with a group of boys who call themselves ‘The A Team’. They seem to have a lot of fun and always have girls hanging around them. Some of them smoke cigarettes and drink alcohol. They steal money from their parents to buy these things. If they can’t get money they steal from the local shop. They say that if Joseph wants to join them, then he must bring cigarettes and money.

- What should Joseph do?

- Selina has met a boy who is much older than her. She is 13 and he is 16 years old. She likes him very much and thinks about marrying him. He wants to have sex with her, but she is not sure. She wants to keep him as her boyfriend but she is worried about AIDS or getting pregnant. She wants to go to university.

- What should Selina do?

Resource 4: Zambian school clubs

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Here is a letter that was sent by two pupils from Lumezi Primary School in Lundazi, one girl and one boy, to a Zambian magazine:

‘We have many clubs at our school, like Young Farmers, Boy Scouts and Girl Guides. People who did not join these clubs had no club to belong to. So a teacher, Mr Kapanda, started a new club for them: the Good Citizens’ Club. It was given this name not because all its members are good, but because Mr Kapanda thought that in the end the members would be good citizens! Now Mr Mtonga is in charge of the club.

Members spend a lot of time helping people: we help the old people, cutting firewood, helping people to cross roads, carrying things. One old woman said, “I was coming from the bush to collect firewood, and there were about a dozen boys who were playing with a ball. Two boys came and took my firewood off my head. I was so relieved that I wanted to pay the boys. But they refused, saying that they belong to a club that helps people!”

Our club has been so magnetic that it now has many more members.’

Here is another letter from pupils of Linda Secondary School:

‘I would like to tell my friends … about our club. It was formed with the aim of giving knowledge to our fellow students about what is happening in the world today. We also try to bring international friendship to students of different nations and characters.

We discuss political topics. And after that we publish our ideas in the weekly school magazine, so that others can share them. Also, we invite different top officials to speak. We make trips, and have had a film show.

I would like to tell students in other schools to form similar clubs. They not only help to spread knowledge, but also give us experience in reasoning and debate.’

And here is one from Senanga Secondary School:

‘In our school we have a club called the Journalism Club. This club produces a magazine for the school every week. In the magazine we write about things happening both outside and inside school. Through your … magazine we would like to inform all clubs like ours that we can exchange ideas and magazines with them.’

Section 2 : Investigating our place in the community

Key Focus Question: How can you use storytelling and local knowledge and culture to enhance learning?

Keywords: cultures; community; role play; discovery; behaviour; storytelling

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- found out more about the local community through discovery learning;

- used role play to identify acceptable behaviour in different situations;

- used storytelling to develop pupils’ awareness of different cultures.

Introduction

Discovery learning, stories and role play are active ways to explore the different communities in which pupils live. They allow pupils to find out things for themselves – which is much better than you just telling them how things are.

The purpose of using stories and role play is to stimulate discussion and help pupils to look at their own attitudes and behaviour in a non-threatening way. Because these scenarios are more removed from the pupils’ real situations they may find it easier to talk more freely.

It is important that life skills lessons do not preach, but help pupils to find out for themselves and think about their own lives and ambitions. You need to be aware that different children will ‘discover’ different things about themselves, others and their lives.

There are some notes about communities in Resource 1: What is a community?

1. Exploring the local community

Discussing and writing stories helps pupils to say what they think about different situations. Stories can be very helpful when you want pupils to think about difficult subjects. But it does take time to prepare them well; you need to think about the communities your pupils are part of and prepare your story carefully.

In Case Study 1, we learn about Mrs Otto who teaches Primary 6 in a large primary school in Kampala. She wanted her pupils to think about community relationships in their own town situation and then find out more about a rural community. If you work in a rural setting, you may want your pupils to explore an urban or town situation.

Activity 1 uses discovery learning to help your pupils ‘discover’ more about their own communities.

Case Study 1: Using your experience to discuss community life

As Mrs Otto came from a village more than 200 km from Kampala, she knows quite a lot about village life. From her own experience, she was able to prepare stories about her life there to use with her pupils. Using her own experience was important for Mrs Otto in teaching as it meant she was more confident about her subject knowledge.

Mrs Otto asked two pupils from her Primary 6 class to read out a story she had prepared about a village community in Uganda and then another two pupils to read one about a small urban community she knew. She had chosen these stories because they had many similarities.

After each story, she asked her pupils to discuss in their desk groups:

- the different activities the people carry out to make a living;

- the people who help others in the community;

- the problems of each community – which were the same? Which were different?

- the leaders of the community.

Mrs Otto asked the groups to feed back their ideas and she wrote the key points on the board. As a class, they discussed the successes and the problems of the different communities and how the problems might be solved.

For homework, she asked them to think about their own community. Next lesson, after having done some research (see Key Resource: Researching in the classroom) each group of four wrote their own description of their community. Some pupils read these out to the whole class.

Activity 1: Discovery learning in the local community

- Ask your class to brainstorm some of the main groups in the local community. These might include NGOs, religious groups, friends, family, community leaders etc.

- Organise your class into suitable sized groups. (This may be according to age or ability or another grouping.)

- Explain that they are going to find out about one of these groups.

- Allow each group to select a community group. More than one group can investigate the same organisation, as they will have different interests and views.

- You may need to do some research yourself or your pupils could do it to find out more about each organisation. You or they could perhaps collect some documents to help with their investigations. Each group could also devise a questionnaire and interview people from the organisation. See Resource 2: Sample questions pupils might ask to find out more about local community groups.

- Give them time to do the discovering, or research.

- Next lesson, ask each group to prepare a presentation on their organisation – the presentation could be written, a poster, a picture or any other display method.

- For younger pupils, you could investigate one group only and invite someone from the organisation to talk to the class and together make a poster. You could repeat this at intervals so that your pupils find out about different organisations.

2. Using role play to explore community relationships

Respecting others and behaving in appropriate ways between different generations is important in holding communities together. In your classroom, how your pupils speak and interact with each other can affect their interest in school and learning. Role play can be used to explore how to behave in different situations. See Key Resource: Using role play/dialogue/drama in the classroom for guidance.

You will need to spend some time preparing appropriate role plays. Remember, the purpose is to help your pupils explore their own beliefs, knowledge and attitudes, and role play is a non-threatening way to do this.

Case Study 2 shows how one teacher used role play with younger pupils to explore the rules of behaviour in their families. Activity 2 uses role play to investigate community relationships.

Case Study 2: Family rules

Mrs Mjoli teaches Grade 3 in Cancele School in Eastern Cape. She asked her pupils to talk to their grandparents or other older family members and ask them about the rules of behaviour that are used in their families.

The next day, in class, they shared the rules from their different families and found that many were the same. One or two children had rules the others did not have, and they talked about why some families need different rules. They found that most of the rules were for children! (Resource 3: One family’s rules has some rules you could discuss with your class.)

Mrs Mjoli chose small groups of pupils to perform a role play about one of the rules. This helped the class to discuss the behaviours shown and when the rules are used.

They found that there were sometimes different rules for boys and girls. They talked about this and found that there were specific tasks to be carried out by boys and different ones for girls. They felt that, mostly, the girls were not treated as well as the boys. In the end, the whole class agreed it was not fair and that the rules should be the same for everyone.

At the end, Mrs Mjoli explained why the rules are important. She also made a note in her book to plan a lesson on gender issues to further explore and possibly challenge the differences in the treatment of girls and boys.

Activity 2: Using role play to explore community relationships

Prepare some role plays set in different community situations:

- Thabo meets the chief

- Mr Ntshona the storekeeper

- Danisile and his grandfather

(See Resource 4: Role play on community relationships for more details on these ideas. You could add your own activities.)

Ask your pupils to act out each role play and have a class or small group discussion after each one. Identify the good or bad behaviour. Ask the class how the people in the story should behave.

Ask the pupils, in groups, to think up their own story to role play. Guide them to make sure they think of relevant situations. Allow each group to present their role play, and repeat the class or small group discussions to think about ways to resolve the situations.

3. Learning to respect differences

It is very important that as your pupils grow up, you help them learn to respect people’s different opinions and beliefs. Stories are a good way of introducing ideas about cultural interactions and good and bad behaviour. Stories can help pupils understand the principles behind different kinds of behaviour.

To use stories well, you should include characters who behave in different ways. A lot of discussion can come from a well-chosen story, but you also need to think about questions you can ask.

The same is also true of role plays. By inventing characters and acting as them, pupils can explore the kinds of cultural conflicts that might occur in real life, but without suffering any of the consequences. Stories and role plays can help your pupils develop their understanding of difference in a non-threatening way. Resource 5: Intercultural communities will help you develop these ideas with your pupils.

Case Study 3: Using storytelling to explore community conflicts

Mr Cole decided to teach his class about the importance of people respecting different members of the community and the roles they play, and the dangers that come from conflict. He used the story of the fight among different ethnic groups in Thokoza township east of Johannesburg to discuss these issues. See Resource 6: Conflict in the community for a copy of this story.

Before he told the story, Mr Cole asked his pupils to listen carefully and try to identify the original reason for the conflict. After hearing the story, they shared their ideas and he listed these on the board.

Next, he asked them, in groups, to describe to each other how the events had developed stage-by-stage. After ten minutes, they talked as a class and compiled the different stages on the board.

Mr Cole then asked them to discuss how they would have stopped the trouble by looking at each of the different stages and describing how they could have controlled each one.

Finally, he asked them to list the ways in which the three different groups contributed to the community and also interacted with each other positively. This helped them understand how each group was important and couldn’t operate without the help of the other groups.

The pupils found this lesson interesting, and Mr Cole saw how they began to treat the issues seriously.

In the next lesson, the pupils worked in groups again to think of any areas of conflict in their own community and some possible solutions. They used the problem-solving skills they had developed when working on the story.

Key Activity: Role play on community interaction

Organise your class into three groups: each will represent one of the communities from the story in Resource 6. Tell them that they will be acting out the conflict and then negotiating the peace, so they need to think through how they will do this. They will need to think about their community’s concerns, and how to present these in their role play.

After 15 minutes of preparation, ask a group of six (two people from each ‘community’) to enact the conflict, as they see it, in front of the class.

Next, ask them to sit down and negotiate the peace while the class watches. Tell them to listen carefully to each other’s points, and address these points in any agreement.

With the whole class, identify and discuss:

- the different concerns that each community had;

- the different solutions that were reached.

Ask them to identify the ideas they could use in everyday life. Which do you think were the best ideas?

Finally, ask them to write the story in their own words and add how the situation was resolved.

Resource 1: What is a community?

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

A community is a group of people who interact and share certain things in common. Members of the community may live in the same area and may have common values and beliefs. They could share some common possessions.

If you are trying to explain the idea of community to your pupils, you might start by using examples they are familiar with. A good starting point is to ask them to describe their families, including the wider family of aunts, uncles and cousins. Help them to realise that their homes and families consist of individuals, a collection of people, living in a particular place – a small community.

Building on this, you can ask them to add in other groups that they interact with and who form part of the wider community:

- their neighbours, who live in the same street;

- their friends, who they see every day;

- their parents’ friends, who visit them.

It is this collection of different groups of people that makes up a community, and it is how pupils interact with these groups that contribute towards who they are and how they see themselves within the community. Identifying the different things that help define a community will help them understand the part they play in different groups. You might ask them to describe:

- the location – where people live;

- the language – how people speak;

- the culture – what clothes people wear, the food they eat, their religion;

- the history – important events that have happened to a group of people.

Resource 2: Sample questions pupils might ask to find out more about local community groups

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

- What is the name of your group?

- What is the purpose of your organisation?

- Which members of the community do you help?

- How do you provide that help?

- Who are the members of the organisation?

- Who can be a member of your group?

- How do you become a member of the group?

- Do you meet regularly? If so, when and where?

Resource 3: One family’s rules

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

One family’s rules

Children do as they are told.

Girls help their mothers with the household duties.

Boys help their fathers and uncles on the land.

Children are quiet and respectful around old people.

Children leave the room when a visitor comes.

Children cannot play outside the home on Sunday.

Older children look after younger children.

Never tell lies.

Resource 4: Role play on community relationships

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Here are some ideas for role plays you can do with your pupils. They are just ideas to get you started. Can you think of more relevant situations for your own community and pupils? If so, write your own role plays or adapt the ones below.

You can stop each story where we have left it and ask the pupils to make up their own endings. This way, the pupils can work in groups and come up with different solutions to the problems. Or you can write your own ending to the story to make any points you wish.

Thabo meets the chief

Thabo had a problem with his neighbour who kept letting his goats into Thabo’s garden where they would eat all his vegetables. It had happened many times. Thabo tried to talk to his neighbour but he would not listen. His neighbour used to be very friendly, but lately he was often in the beer parlour and did not care much about his house or his friends.

Thabo decided to go to the chief to ask for some advice. …

Mr Ntshona the storekeeper

Mr Ntshona has a small store that sells food and household items. His store is a great help to the women in the village as it saves them walking so far to the next town. Mr Ntshona is the proud owner of a refrigerator and a generator. Now he can also sell cold things, like cool drinks and milk – even meat. The young people like to come to his shop to buy cola. One day, Mr Ntshona found that while he had been busy serving one boy with some sweets, two other boys opened his fridge and stole two bottles of cola. He was very upset and he decided to ….

Danisile and his grandfather

Danisile’s grandfather is very old – he is 92! He lives with Danisile and his three sisters and his mother and his aunt and her baby. Most of the time grandfather stays in his room or on his special chair outside the front door under the shade of the mango tree. He is often grumpy and complains about the noise the children make. Danisile’s mother tells him they must look after grandfather as he is the head of their household. He has his old age pension from the government, which helps to buy their food. Danisile is quite scared of him and prefers to let his sisters look after grandfather.

One day, his sisters are all out fetching water and mother tells Danisile he must take grandfather his evening meal. Danisile is very worried. He takes the food and then ….

Resource 5: Intercultural communities

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

As you help your pupils define their communities, be it their family, village or school, it is very important that they also learn to respect people’s different opinions and beliefs.

Remind pupils that they are all individuals from different homes and families. For example, they might not all speak the same home language or mother tongue. Their parents may have different occupations: some may be labourers; others farmers; a few may be traders, nurses etc.

But also highlight the fact that they are all members of the same community, with a common interest. Because of this, they should respect the views of other people in that community.

The first stage of respecting other people is to listen to their views and recognise their value. When pupils learn about different people’s backgrounds and beliefs, they will be able to respect each other more. They will not be fearful of cultural differences. They will also have a greater understanding of who they are.

Cultural differences can sometimes be a cause for conflict within a community. It is important for pupils to understand the reasons for conflict, such as arguments over property and land, behaviour, money and relationships. An important part of life skills education is finding ways to try and avoid conflict at school and in the community.

Resource 6: Conflict in the community

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

In the mid-1990s, the township of Thokoza in South Africa was in the news headlines when, during the final throes of Apartheid, civil war broke out between the ANC and the Inkatha parties. As the township descended into chaos, rather than intercede to stop the fighting, the South African government – at the time, struggling to maintain what little hold it still held over the country – began a systematic campaign to encourage the fighting. At different times, the government actually provided arms to both the ANC and Inkathas; when opportunities arose to mediate the conflict, the government turned a blind eye. Before the conflict ended, over 2,000 people had died.

This morning, we visited TshwaraganoPrimary School in the heart of the Thokoza township. Two of the teachers spoke to us about life during the war in Thokoza. The school, it seems, was located right in the heart of the fighting, and frequently became caught in the crossfire. On those days, students and teachers had to ‘run for their lives’ to dodge the bullets, which lodged themselves into the side of the school. Despite this, the school remained open. They ran for their lives one day and returned to school as normal the next. I asked the teachers why they didn't close the school. They said: ‘Because we are teachers. That is what we do. They are students. This is where we belong.’

Ten years after the Thokoza conflict, the area of highest violence down the street from the school has been turned into a memorial so that townspeople will never forget the lives lost. Although the area is still populated by shanties, the school continues to thrive, in part with the support of the Global Education Partnership, but primarily due to the resilience and determination of the teachers and families in the Tshwaragano school community.

Adapted from: Website Discovery Educator Network http://discoveryeducatorabroad.com/ node/ 167 (Accessed 2008)

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following sources:

Other:

Adapted from: Website Discovery Educator Networkhttp://discoveryeducatorabroad.com/ node/ 167 (Accessed 2008)

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. If any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

Section 3 : Ways of taking responsibility

Key Focus Question: How can you link home and school knowledge to help school achievement?

Keywords: group work; discussion; taking responsibility; achievement; home links

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used linking activities at home and at school;

- used group work and discussion to identify how beliefs and values relate to classroom behaviour;

- helped pupils make their own rules for classroom behaviour.

Introduction

Helping your pupils to want to take responsibility for their own learning is an important task.

Part of this means involving pupils in managing the classroom and its resources. In this section, you work with your pupils to make the classroom a more effective place, by explaining and then giving out particular responsibilities.

You will also encourage pupils to develop their own classroom rules, by showing how their beliefs can apply to their behaviour in the classroom. Having these rules will benefit both you and them. Showing respect and trust in your pupils will have a positive influence on their attitudes as people and learners.

It may help to read Resource 1: The benefits of classroom principles before starting this section.

1. Working in groups

Every community has different beliefs and values, guided by the customs of the local society. These beliefs and values help to determine what behaviours are acceptable in that community.

Pupils will first learn these standards at home, and this can be useful to you. You can draw on their families’ expectations to help identify the ways pupils and staff are expected to behave at school:

- in the classroom;

- in the playground;

- towards the teacher;

- towards each other.

Developing the principles of good behaviour with your pupils will assist their concentration during class. They are more likely to listen to what is being said and treat each other respectfully.

In addition, by finding out ideas from your pupils, they will feel that they have agreed to any expectations of behaviour. They are more likely to respect these expectations than if you had just told them they must behave in a certain way.

Doing this successfully involves some careful planning and can take some time to develop. At each step, you should listen carefully to your pupils’ ideas.

Case Study 1: Classroom rules

Mrs Aber is a Grade 4 teacher in Uganda. She has 63 pupils. During orientation week, at the beginning of term, she asked her pupils about the behaviour expected of them at home. As she has a large class, she put the pupils into desk groups of eight, to compare their families’ expectations. She asked them to list four rules common to all of them.

The class gave many examples of behaviour their families expected – many of which were the same for different children. Mrs Aber wrote some of these up on the board.

She then asked if there should be the same rules for behaviour in the classroom as at home.

In groups, they chose which home rules could be used in the classroom, and why they wanted to use them.

They then shared their ideas as a class. Mrs Aber was pleased, and used these ideas to establish some principles for behaviour at school, covering:

- how we treat each other;

- how we behave during lessons;

- how we behave during playtime;

- how we treat our things.

They voted on six rules that they wanted to adopt.

Activity 1: Understanding rules

This activity can help explain why we have particular rules, and how they benefit everyone.

Organise your pupils into groups. Ask them to identify five rules at home and five rules at school.

Get one example of a home rule and one example of a school rule from each group. Write them on the board.

Ask the groups to discuss:

- why they think we have each rule;

- how each of the rules helps them.

Discuss their ideas as a class. Prepare to ask questions that will help them think more about their answers.

Draw out the different principles behind rules, by questioning the class: e.g. safety; respect; helping others; helping ourselves. Ask them to link each rule with one principle.

Ask pupils to each write a paragraph about why we have rules. Make a display of these.

How suitable were their suggestions?

2. Sharing responsibility for the classroom

It is important for your pupils to understand that, like their teacher, they have responsibilities within the classroom.

Firstly, you must be a good role model. Show respect for your duties: be punctual; plan and attend lessons; mark homework etc. If you do not fulfil your responsibilities, you cannot expect the pupils to do so.

Secondly, involve them in maintaining standards in the classroom. This includes them:

- cleaning the chalkboard;

- keeping the classroom clean and tidy;

- looking after books and furniture, and so on.

If they look after the classroom themselves, they will start to take pride in it.

Thirdly, involve them in organising their own learning through the activities that you give them. This includes them:

- demonstrating the difference between work time and play time;

- organising group work and study sessions;

- checking each other’s work, and so on.

The usual way to start doing this is by appointing pupils as monitors and group leaders, responsible for looking after different tasks. But they also need to understand what is needed for each task.

For more information see Resource 2: Using monitors.

Case Study 2: Skills and responsibilities in the classroom

Mr Sambawa is a senior teacher with a large multigrade class. He has a group of monitors from the top grades who do small tasks around the classroom and also help the younger pupils. The monitors check their groups are ready at the beginning of each lesson, they look after the textbooks and they clean the chalkboard each day. They are very useful indeed.

On Friday, the class clean-up day, Mr Sambawa asks his monitors to work with their groups from the lower grades to list which areas need action. Each group makes one suggestion, which is written on the board.

Each group volunteers to take one activity and, supervised by the monitor, work on it each Friday break time until the end of term.

At the end of the week, each group explains to the class what they have done and where they have put things. They also give the class suggestions for next week to make the tasks easier or help solve problems.

At the end of term, they review each group’s progress and vote as a class for the best achievement.

Activity 2: Appointing monitors

Plan how you will introduce monitors to help in class.

- Introduce the idea of monitors to the whole class. Explain how a system of monitors will work, and how it will benefit everyone.

- With your class, discuss and write a list of all the classroom tasks that need to be done at the beginning, middle and end of each day.

- Identify which tasks have to be done by you, and which could be done by the pupils.

- As a class, decide how many monitors are needed and then think of a way to select the monitors. You could change monitors every week so that everyone gets a turn and develops responsibility for others.

- Appoint the first set of monitors and explain their tasks. At the end of the first week, review their work with them and with the class.

- Ask them to suggest new tasks they could do.

Once the monitor system has been running for a little while, take some time to think about how it is working:

What impact does having monitors have on the behaviour and work of your class?

Do the pupils like the system?

Does it need to be reviewed – and perhaps modified – by the class?

3. Working in groups to agree classroom rules

In this section, you will use pupils’ ideas about good principles of behaviour to help them develop their own classroom rules.

Helping pupils make a set of rules for the classroom is one way to strengthen participation and responsibility, especially if they write the rules themselves. Establishing their own rules will help them understand what is expected.

There are two sets of rules to think about. The first are social rules. These cover the ways people interact with each other and behave towards each other.

The second are study rules. These cover how pupils behave during lesson time and what they can do to help everyone study and learn. By organising pupils to work in groups, you will allow them to share ideas and gain respect for each other more.

It is important that the rules apply to the teacher as well as the pupils. You need to be a good example for your pupils. If you respect them in the classroom, they will learn to respect you. One teacher describes her experiences in Resource 3: Asking children to agree rules.

Case Study 3: Developing rules for behaviour

Ms Okon asked her Primary 3 class to think about the principles of behaviour they had identified earlier and how these might help them develop their own classroom rules.

She asked pupils to think about their different responsibilities. What things could they do to help each other fulfil those responsibilities?

They first talked together in pairs, and then as a class. Finally, in small groups, she asked them to write sentences using: ‘We should …’

She went around each group and asked them to read one sentence and explain why they had written it. For example: ‘We should be quiet in class because it helps us listen better’.

If pupils suggested negatives, for example ‘Don’t talk in class’, together they changed it to something positive: ‘We should try to listen carefully to each other’.

She was very pleased with their responses, and collected their sentences in. The next day, they reviewed them all again and chose eight. Ms Okon then wrote these on the chalkboard and the pupils copied them into their books for reference.

Key Activity: Developing classroom rules

- Discuss with your class why we need class rules for behaviour and for study. Discuss why they – and not you – will write the rules.

- Let the pupils, in groups, discuss their suggestions for social rules and study rules. Ask them to write five rules for each, using positive sentences.

- Collect each group’s suggestions on social rules and write them on the board. Ask them to explain to the class why they are important.

- Organise a vote: ask each pupil to choose six to eight rules from the board. Too many is unnecessary if you have good rules. Read out each rule, and count the number of hands up for each rule. Write the numbers down and identify the most popular.

- Do the same for study rules.

- Organise the class to make a poster of the written rules. Display it by the door of the classroom to remind everyone as they come in.

- Monitor how they work over a term and review the rules if necessary. How would you and they modify them? (See Key Resource: Assessing learning).

Resource 1: The benefits of classroom principles

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

There are many benefits to having well-established principles in your classroom.

A clear set of guidelines about what is good and unacceptable behaviour in the classroom helps you manage the class better. By capturing these as rules, you are able to refer to them if it’s needed. However, for rules to be effective in a positive way, the pupils also need to understand why a particular rule exists.

These guidelines help the pupils understand what is expected of them. They know what is appropriate behaviour during lessons and during break time. They also have some idea of how to interact with each other and why.

A set of rules for behaviour makes it easier for you to organise the pupils when doing activities in the classroom. They will know when to listen, when to talk, how to respond to questions, and so on.

Having guidelines on behaviour means that the pupils will get into the habit of treating each other well. This makes for a peaceful and cooperative classroom.

By allowing the pupils to write their own rules and take responsibility for classroom activities, you will be encouraging them to take pride in their schooling. They are also more likely to follow those rules they have written themselves.

The above will all contribute towards a positive learning environment in your classroom. You will be able to spend more time on teaching and less time on controlling and organising the class. The pupils will listen better in class and concentrate on their activities. They will also learn to help each other and support themselves in their studies, which should result in higher achievement. They will feel better about themselves as people as they make progress in their learning and you will enjoy teaching them more.

Resource 2: Using monitors

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

As a teacher, you can use pupils to help you with the day-to-day management of your classroom. There are numerous simple tasks that you can ask them to perform on your behalf, and this serves two benefits.

- It allows you to spend more time preparing and delivering good teaching, rather than managing and tidying up the classroom;

- It gives the pupils small areas of responsibility, which encourages them to take pride in their schooling.

There are a few issues you need to think about when selecting monitors. You want pupils who will do their tasks well, and who will be willing to help you and others.

You also want pupils who are responsible and interact well with others. Sometimes, pupils might see being a monitor as a position of power over others, and they might misuse it. It is important to help them understand that they have to carry out the role responsibly, and you will be a role model in this. All pupils should be given a chance to take on such roles. If you only choose the same pupils each time, others will feel less valued. You will need to provide guidance and support to the monitors. Some will need more support than others in the early stages.

You will need to think clearly about each of the jobs before you give them out. If there is not a regular daily task to do, the pupils will get bored and neglect it. There needs to be a clear purpose for the task as well, rather than something to fill time. Finally, you will also need to provide clear instructions.

It is important to share the jobs around and give each pupil a turn. If some pupils are not involved, they will stop taking an interest and may even start disrupting classes to get the attention that is going to the monitors.

If possible, let pupils choose the jobs they could do to help. You can also hold regular classroom meetings where pupils can suggest different tasks.

Finally, you will also need to monitor and support them. Give praise where you can and give guidance where it is necessary.

Resource 3: Asking children to agree rules

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

I would like to share some stories that happened in my classroom. In the first few days of school, one of our activities is to get together and talk about the classroom and playground rules. In the beginning, I told the children the rules and we talked about them. I wondered if they are too small (4–5 years old), to come up with the rules but last year I decided to let them generate the rules. To my surprise, it went OK, and my children were even stricter than me, and generated more rules. My class really enjoyed this activity and they follow the rules they have generated themselves voluntarily.

Using the children’s misbehaviour/mistakes to teach them how to behave well is a good theory. When a child misbehaves in our classroom or during outdoor activities I frequently try to make use of the opportunity to talk about it with the children during class meeting later that day. We talk about what happened and I ask the children to find a solution, not a punishment for the problem. It’s true that sometimes my children do suggest silly ideas, but gradually, more often than not, my kids find a good solution to the conflict.

As expected, it takes time and persistence from the teacher, especially with little ones, to show the way and make the kids understand that they have the power to decide how to solve conflict on their own peacefully, but it is extremely rewarding in the end.

Thank you,

Zsuzsanna

Nigeria

Section 4 : Investigating self-esteem

Key Focus Question: How can you use stories and other activities to develop and assess pupils’ self-esteem?

Keywords: self-esteem; relationships; group work; community activities; assessment; stories

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used different activities and ways of grouping pupils to develop self-esteem;

- developed your understanding of factors that can influence self-esteem;

- planned a community-based activity;

- used ways of assessing learning.

Introduction

This section looks at how to introduce pupils to the nature of different relationships and to help them understand that these relationships can either support or undermine self-esteem. The impact of such relationships on pupils’ education can be significant. As a teacher, you have the responsibility to do your best to provide a supportive learning environment.

The ‘African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child’ (page 2) states that:

‘In all actions concerning the child undertaken by any person or authority the best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration…

…Parties to the present Charter shall ensure, to the maximum extent possible, the survival, protection and development of the child’

This section raises, but in no way covers the complexities of the issues surrounding abusive relationships and inappropriate behaviour. It explores how these can affect pupils’ learning and self-esteem and provides you with a small insight into your roles and responsibilities and the need to seek help from other professionals when you are concerned

Finally, we discuss how you can encourage pupils to work together and help those who are having difficulty.

1. Using a story to discuss self-esteem

Self-esteem is a major key to success in life. If you feel good about who you are, you have more confidence to join in with others, to make new friends and face new situations.

As a teacher, you play a crucial role in developing pupils’ self-esteem through the way you interact with them. You need to be sensitive towards pupils’ feelings and emotions, and you need to be careful about what you say and how you speak to them.

It is important to be positive and encouraging, praising them for their hard work and achievements and using kind words wherever possible. Try to catch them being good, rather than looking out for bad behaviour. This does not mean that you do not have to discipline pupils, but how you do this is crucial if you wish to maintain a positive working relationship with them.

It is always useful to start off a new topic by finding out what your pupils already know. Ask them for ideas about self-esteem – you may be surprised at the variety of answers they come up with.

Case Study 1 and Activity 1 show how you can use a story in different ways to explore an idea such as self-esteem.

Case Study 1: Addressing issues of self-esteem

John Nvambo in Nigeria has a good relationship with his 36 Primary 4 pupils. One day, he noticed that not all of his pupils were contributing in class anymore. Some were now shy and withdrawn, and didn’t ask him questions. He also noticed that this was affecting their grades, so he decided to address the problem.

The next morning, John told the story of three children to help introduce the idea of self-esteem (see Resource 1: A story about self-esteem).

He then divided the class into three groups, A, B and C, directing each group to list the qualities of a person with either:

- healthy self-esteem;

- low self-esteem; or

- overrated self-esteem.

Next, John organised them into threes, one from each group, to share their ideas before talking together as a class.

They were able to identify the different characteristics, and why they were good or bad for the individuals involved. From this, they were able to talk about how to get a balance of self-esteem by using an activity like the one in Activity 1.

Activity 1: Developing self-esteem

Adapt Resource 1 to help you with this activity.

- Divide the class into groups. Call the groups either As or Bs.

- Ask the A groups to help the arrogant boy develop balanced self-esteem.

- Ask the B groups to help the boy with poor self-esteem to develop confidence.

- Monitor group discussions to check that all pupils are participating.

- After 15 minutes, match each A pupil with one B pupil. Ask the pairs to compare ideas and make suggestions for each other.

- After ten minutes, have a class discussion about ideas for helping first the arrogant child and then the timid child.

- Finally, as a class, list the main features of healthy self-esteem and how it helps pupils to gain from one another.

Did this activity have an impact on the behaviour of your pupils towards each other?

2. Using role play

Unfortunately, as some of your pupils grow up they may encounter an abusive relationship. This type of relationship can influence their social, emotional and physical development for the worse, and it takes more time and effort to help them overcome the damage done.

The concept of ‘abuse’ here should not be confused with offensive and insulting language. ‘Abuse’ in this sense occurs when individuals use other people in a wrong and improper way. Relationships of this kind leave a lasting psychological, emotional and physical impact on the abused person. There are several types of ‘abuse’, such as physical and mental abuse. There are examples of these in Resource 2: Types of abuse, which you should read.

As a teacher, your responsibility is to help your pupils learn. If they are not happy or are being abused, they will not learn. Your role is to protect your pupils and you may need to involve others who are more expert and can give counselling. Resource 3: The role of school teachers provides more detail on your role.

The best way you can help is to explore with your pupils what they understand about correct and incorrect behaviour in relationships. However, you must do this sensitively and carefully. Resource 4: Finding out what pupils already know about relationships shows how one teacher did this. You could use the same method with your own pupils.

Case Study 2: Child labour

Sara Nduta, a teacher of Standard 5 in Kibera Community School, Nairobi, brought in the local government welfare officer to talk to her class about child abuse.

The welfare officer began by telling the pupils that using young people to work in trade and on farms had been a common practice in most parts of Africa. It was a way of bringing up the young ones to learn skills and responsibility, and to be self-reliant.

But with the ‘UN Rights of the Child’ (see Introduction), he said that the government disapproved of using children as street hawkers and farmhands where they were exploited and made to work long hours. It was dangerous to their health, sometimes leading to death. It took children from school and education, and sometimes led them into crime.

The welfare officer said that parents sometimes argue that they need their children to bring in food and money for the family. However, he said that the government regards it as unlawful, as all children have the right to free schooling, and that any community needs to tackle the issue.

Following the talk from the welfare officer, the next day, Sara’s class did a role play on child abuse. They demonstrated it first for the whole school, and then for the Parents-Teachers’ Association (PTA) committee (see Resource 5: Responses to the role play).

Activity 2: Role play on child abuse

Plan a role play for your class that deals with the issue of child abuse. You need to think carefully about this. It can be a very sensitive issue for young people, so you will need to be careful how you organise such activities.

First, list the different forms of child abuse and their outcomes. Choose which of these you want to focus on in class.

Think how you will introduce these issues to the class. For the role play, decide on the pupils’ different roles. What are the issues for each role?

Plan how many pupils will be in each group, and how they will prepare and perform their role plays. How will you explain this to them?

Finally, how will you summarise the main points with them after they have performed the role plays? Will you have a discussion? How will you manage it?

To help you, use the Resources for this section and Key Resource: Using role play/dialogue/drama in the classroom.

3. A community project as a source of learning

It is important that pupils develop ways to reflect upon how different relationships work so that they can make friends and protect themselves from harm.

One way to do this is to help the pupils work with the community to address a particular issue. Activities like these bring pupils together with the community to find common solutions to a community problem. Pupils learn about relationships through working with others, by:

- sharing information with local experts;

- learning how groups work together;

- learning how to accept and fulfil responsibilities;

- learning how to treat each other properly;

- bringing together different ideas to help solve a problem.

Planning and organising an activity where the pupils work with other people in the community can be difficult. You need to organise a task that the pupils can realistically contribute to and you need to choose people who are willing to work with children. You also need to plan with them how the interaction will work – it may need to take place over two or three weeks or longer. It is important that everybody involved – adults and children – knows what is expected of them.

Before starting this section, we suggest reading Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource.

Case Study 3: A community environmental campaign

Mrs Wanjiku was talking with her Standard 6 pupils about keeping their surroundings clean. She asked them to think of things in the community that needed cleaning up.

One thing they mentioned was the number of plastic bags in the street. The bags caused problems by blocking water channels. Sometimes, cows and goats would eat them and get sick.

Mrs Wanjiku’s class decided to start a community campaign. They spoke to the local environmental officer and he came to help them plan their campaign in class. They also spoke to the market traders’ committee and they organised the campaign together.

The environmental officer organised a community event and got some sponsorship from a local NGO working on the environment. The market traders told their customers about it. Having discussed the issues with the environmental officer, Mrs Umar organised her pupils to:

- design a poster campaign;

- write a drama and a song;

- organise a debate for the event;

- organise a clean-up campaign.

The event was a big success. The market traders displayed the posters on their stalls, explaining the issues to their customers.

One Saturday, the whole school picked up bags in the street and out of the water channels. With help from the market traders and the environmental officer, the village was much cleaner now.

Key Activity: Assessing the learning of pupils

First, read Resource 6: Guidelines for planning a community-based activity and Key Resource: Assessing learning. If you are going to organise a community-based activity for your pupils, plan how you will assess what they have gained from the relationship. Carry out the activity with your class.

Afterwards, ask them to discuss with each other and then write about their activities, explaining:

- what information they used;

- what activities they did and the skills they developed;

- how they interacted with the other people involved, and who did what;

- how they organised their work.

Once they have done this, you should have evidence of the new skills and knowledge they have developed. Encourage them to think about how effective their event was.

Now, ask them what new things they have learned. Ask them to discuss it in groups and then write a list.

Finally, ask them to describe:

- how they plan to use their new skills in the future;

- who they would like to work with next.

Did the pupils find this activity stimulating? How do you know this? How could you use this kind of activity again?

Resource 1: A story about self-esteem

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

There were three children who lived in the same village – two boys and one girl. One day, they all started going to school. Because they were the same age, they all attended the same class, but they reacted in very different ways.

The first boy was clever, and started to do very well at school. He could answer many questions and always got good marks. But because of this, he started to think a lot of himself. He didn’t want to listen to other people’s views. He became arrogant, and thought he knew everything. He was rude to others, and so he started to lose friends.

The second boy found school difficult, and didn’t understand some things. But he was afraid to ask the teacher in case he was punished. He fell further and further behind in his studies. Because of this, he thought poorly of himself. He thought his classmates were making fun of him. He felt unwanted and thought he was looked down upon by the teacher, and so never talked in class.

The girl enjoyed going to school from the beginning. She liked making friends, and realised she could learn a lot from them. She had good learning abilities but liked sharing ideas with others. She was good at listening to others. She had a good sense of humour, but learned not to make too much noise. She could ask questions when it was needed, but knew not to demand attention from everyone.

Resource 2: Types of abuse

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

There are many different forms of abuse – physical, sexual, emotional and psychological. They can take place between adults, between children, or between adults and children.

It is important that your pupils have some awareness of these forms of abuse, because while they are children they are very vulnerable. They trust adults, and usually do what they say, but they need to know that not everything an adult may do is correct.

Physical abuse involves the beating or hitting of someone. It does not have to be hard or violent, but if physical abuse is regular and frequent it can have a bad effect on a relationship.

Sexual abuse is the improper use of another person for sexual purposes, generally without consent or under physical or psychological pressure. This happens between adults and adults, adults and children, and also between children entering into adulthood. The trauma and psychological damage can be very severe and pupils may become very aggressive or withdrawn, nervous around adults or engage in inappropriate behaviour with their fellow pupils.

Emotional and psychological abuse involves treating someone cruelly over a long period, so that it makes them unhappy and depressed. It can involve calling them names or being rude, or just undermining their confidence and belittling their achievements.

There are other examples as well, such as parental abuse. This could take the form of a father luring his son into smoking by fixing a cigarette in his mouth and lighting it up for him. Parental abuse could also be in the form of beating a child regularly and violently so as to inflict wounds on them and suppress and control them beyond reason.

There can be domestic abuse – poor treatment of wives or housekeepers, no matter how hard they work.

Such abuse causes physical and emotional pain, and can lead to depression and low self-confidence.

Resource 3: The role of schoolteachers

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

School teachers are in a position to identify when children are being abused. They have opportunities to get to know individual children well, and thus to notice changes in a child’s behaviour or performance, which could be linked to abuse. Children may also disclose their circumstances as part of life skills lessons or other parts of the curriculum.

If a teacher suspects abuse, a useful process to follow is:

- Start gathering information as soon as you suspect child abuse.

- Continue to do so consistently, and document all information gathered.

- Treat all this information as confidential.

- Discuss your suspicions and the information that you have gathered with the head teacher (unless she or he is possibly implicated).

- Ensure confidentiality by opening a separate file for the particular pupil. This file must be kept in the strong room or safe.

- The head teacher and the teacher must consult the list of criteria for the identification of different types of abuse to verify the information before making any allegations of child abuse. Include in this process professionals who have experience.

- Remain objective at all times and do not allow personal matters, feelings or preconceptions to cloud your judgement.

- Any information to do with child abuse is confidential and must be handled with great discretion.

- The reporting and investigation of child abuse must be done in such a way that the safety of the pupil is ensured.

- Justice must not be jeopardised, but at the same time the support needed by the pupil and their family must not be neglected.

Other important things to remember when talking to pupils are:

- Do not tell a child who discloses abuse that you do not believe them.

- Affirm the child’s bravery in making the disclosure.

- Tell the child what you are going to do about what you have been told, and why.

- If possible, tell the child what will happen next.

- Refer the child for counselling if necessary.

- Be prepared to give evidence in court if there is a trial.

There are many organisations across Africa dedicated to the prevention of child abuse and domestic abuse, for example the African Network for the Prevention and Protection against Child Abuse and Neglect (ANPPCAN). See http://www.anppcan.org/ for more information. Use your preferred search engine to find organisations in your own country that support vulnerable and abused people

Resource 4: Finding out what pupils already know about relationships

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Gathura is a hardworking teacher at a well-organised community school in a village in central Kenya. In her characteristically thorough approach to teaching, she simplified some difficult words that her pupils are likely to come across in their study of ‘relationships’. This is to motivate them and help their understanding.

Gathura asks her pupils to discuss in groups:

- who they spend time with every day at home, and why;

- who they share ideas and experiences with at school, and for what reasons;

- if they interact with their teachers, and why.

After they have discussed these ideas in groups and as a class, she takes it further by asking her pupils what connects them to the provision seller outside their school gate. She asks them to think about which other people from the community they see regularly, and why.

They discuss these ideas in groups and then share them with the class. From this, Gathura is able to help the pupils begin to identify the different kinds of relationships that they have with people, and the kinds of behaviour that are appropriate within each one.

She also used the following group activity to help her pupils explore ideas about relationships.

- Divide your class into manageable groups across genders, personality types and abilities, to work on the relationship questions below.