Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 7 March 2026, 5:06 AM

Module 1: Reading and writing for a range of purposes

Section 1: Supporting and assessing reading and writing

Key Focus Question: How can you support learning to read and write and assess progress?

Keywords: early literacy; songs; rhymes; environmental print; assessment; group work; shared reading

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used songs and rhymes to teach beginners to read;

- used ‘environmental print’ and grocery packaging to teach reading, writing and design;

- explored ways of supporting learning with group work;

- developed your ability to assess learning.

Introduction

What should a successful reader and writer know and be able to do? As a teacher, you need to be able to answer this question so that you can guide your pupils. Learning to read and write successfully takes practice. Therefore, it is important to use a variety of approaches and activities that will keep pupils interested. It is also important to assess pupils’ progress and to ask yourself whether you are meeting their needs. This section explores these ideas as it looks at early literacy.

1. Using songs and rhymes

Learning to read and write is hard work! Because you want pupils to look forward to reading and writing lessons, it is very important that you make your classroom – and the activities that support learning to read and write – as stimulating as possible.

Resource 1: What successful readers and writers need to know explains that pupils need to learn how to connect sounds and letters, letters and words, words and sentences. Songs and rhymes that pupils know well – and to which they can perform actions – help them to make these connections. So does shared reading, in which you read a big print storybook, with pictures, to your pupils. While you are reading, stop to show them each picture and to ask what they think will happen next. When you have finished, use the book for letter and word recognition activities in which you ask individual pupils to point to and read particular letters and words. Remember to give pupils plenty of opportunities to talk about the story – the characters, what happened, how they feel about the story, etc.Section one opening text in paragraphs

Case Study 1: Introducing pupils to reading

Mrs Nomsa Dlamini teaches pupils to read and write in isiZulu in her Grade 1 class in Nkandla, South Africa. Nomsa reads storybooks to them, including some that she has written and illustrated herself because there are few books available in isiZulu.

At the beginning of the year, she makes sure that all pupils understand how a book works – cover, title, illustrations, development of the story – because she knows that some of them have never held a book before starting school. She has found that prediction activities, in which pupils suggest what will happen next in the story, are useful and stimulating for her pupils.

Nomsa realises that pupils need a lot of practice to give them confidence in reading. She makes big print copies of Zulu rhymes or songs that they know well and also ones that she knows are particularly useful for teaching letter-sound recognition. Pupils say or sing them and perform actions to them (see Resource 2: Examples of songs and rhymes). Most importantly, she asks individual pupils to point out and read letters and words. Some pupils find this difficult so she notes their names and the letters or words they have trouble with. She prepares cards with pictures, letters and words to use in different ways with these pupils, either individually or in small groups, while the rest of the class are doing other activities. Nomsa is pleased to find that this helps the confidence and progress of these pupils.

Activity 1: Using songs and rhymes to teach reading

Ask pupils to:

- choose a favourite song/rhyme;

- sing/say it;

- watch carefully, while you say the words as you write them on your chalkboard (or a big piece of paper/cardboard so you can use it again);

- read the song/rhyme with you (do this several times);

- point out (individually) particular letters or words or punctuation (capital letters, full stops, question marks);

- decide on actions to do while singing the song/saying the rhyme;

- perform these actions while singing the song/saying the rhyme again;

- sit in groups of four and take turns reading the song/rhyme to each other.

Move round the class, noting pupils who find reading difficult.

End by asking the whole class to sing the song/say the rhyme, with actions, again.

.2. Using packaging to help reading

Some pupils grow up in homes that are rich in print and visual images: grocery boxes, packets and tins, books for children and adults, newspapers, magazines and even computers. Others have few of these items in their homes. Your challenge as a teacher is to provide a print-rich environment in your classroom. One way of doing this is to collect free materials wherever possible. Packaging materials (cardboard boxes, packets and tins) often have a great deal of writing on them and even very young pupils often recognise key words for widely used grocery items. For more experienced readers, magazines and newspapers that community members have finished with can be used for many classroom activities.

This part explores ways to use such print to support learning to read.

Case Study 2: Using grocery packaging for reading and writing activities

Hajiya Binta Faruk teaches English to 45 Primary 4 pupils in Lokoja, Kogi State. They are not very familiar with English but they recognise letters and some English words on grocery packaging.

Binta asked her neighbours for empty boxes, packets and tins. She brought these to school to use for reading and writing activities.

Her pupils’ favourite game is ‘word detective’. Binta organised the class into nine groups of five and gave each group the same box, packet or tin. She asked pupils to write down numbers from 1 to 5 and then asked five questions (see Resource 3: Example questions to ask about a grocery item). Pupils compared individual answers and decided on a group answer. Binta discussed the answers with the whole class. The ‘winner’ was the group that finished first with most correct answers.

Sometimes Binta invited each group to ask a word detective question.

To encourage pupils to think critically, she sometimes asked questions about the design of the packaging and the messages in the advertising.

Binta noticed that some pupils didn’t participate, so the next time they played, she asked every pupil to write down four words from the grocery ‘container’ before they returned to their usual seats. Back at their seats she asked each one to read their list to a partner. She discovered six pupils who needed extra help and worked with them after school for an hour, using the same grocery items and giving time to practise identifying letters and words.

Binta realised becoming familiar with letters and words on packages helps pupils to identify these letters and words in other texts they read, such as stories. By copying words from packages, pupils also learn to write letters and words more confidently and accurately.

Activity 2: Using groceries for reading and writing activities

Bring to class enough tins, packets or boxes for each group of four or five pupils to have one item to work with or ask your class to help you collect these items.

Write questions on the chalkboard about the words and images on the packet, tin or box (see Resource 3). Either ask your pupils to read them or do it for them.

Either play the word detective game in groups (see Case Study 2) or ask pupils to write individual answers, which you assess. Arrange to give extra practice time and support to pupils who could not manage this activity.

In the next lesson, ask pupils to work in the same groups to design the print and visual information for the packaging of a real or imaginary grocery item.

Ask each group to display and talk about their design to the rest of the class.

What have pupils learned by reading the packages of grocery items and by designing and displaying their own? Compare your ideas with the suggestions in Resource 3.

3. Motivating pupils to read

Reading and writing can be very exciting and stimulating, but some pupils develop a negative attitude to these activities. This might be because they find reading and writing very difficult, perhaps because they are bored by reading and writing tasks that always follow the same pattern, or perhaps they don’t see much value in reading and writing. One of your challenges as a teacher is to stimulate pupils’ interest in reading and writing and keep them interested. Case Study 3 and the Key Activity suggest activities that may help pupils to become more interested and confident in reading and writing.

Case Study 3: Reading neighbourhood signs and writing about them

Mr Sam Imasuen teaches English to a Primary 5 class in St John Primary School, Benin, Edo State. Benin is a densely populated area with many examples of environmental print around the school – mainly in English but also in several local languages.

To generate income, people have set up ‘backyard businesses’ such as grocery shops, barber shops, panel beaters and phone booths. These all have homemade signs and some also have commercial advertisements for various products. There are schools, clinics, places of worship and halls, most of which have signs and noticeboards. On the main road, there are signs to many places, including the famous University of Benin.

Mr Imasuen planned a route around Benin that would give pupils opportunities to read and make notes and drawings about different examples of print and visual images. He also prepared a list of questions to guide their observations.

Mr Imasuen has 58 pupils in his class, including ten who have recently arrived from Ghana. He decided to ask two retired multilingual friends to assist him with this activity. One speaks Akan, the language of the Ghanaian pupils. The class went out in three groups.

Mr Imasuen’s friends participated in the classroom discussion and the writing and drawing activity that followed. By the end of the week, the three men agreed that pupils had become more aware of how information can be presented in different ways and in different languages and some seemed more interested in reading and writing than before.

Key Activity: Reading signs

Before the lesson, read Resource 4: Preparing for a community walk to plan the walk and prepare your questions. Write the questions on the chalkboard.

To begin the lesson, tell pupils about the walk and, if they are able, ask them to copy the questions from your chalkboard. If not, have the list of questions ready for each group leader to ask on the walk.

Take them for the planned walk through your local community.

While walking, they must give or write answers to the questions and draw examples of the print and visual images they see.

Afterwards, ask pupils in groups to share what they saw, wrote and drew. Ask the whole class to report back and record key points on the chalkboard.

Ask each group to design, write and draw a name, sign, notice or advertisement they think would be helpful to have in their community. Help them with any difficult words. Younger children may need to work in small groups with an adult to help them.

Ask each group to show their design to the whole class and explain the choice of language, visual images and information.

Display these designs in the classroom for all pupils to read.

Resource 1: What successful readers and writers need to know

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

The language in which they are expected to read and write

If pupils have to learn to read and write in a language that is not their home language, this makes the task much more difficult. In this situation, teachers need to start with oral work and vocabulary building in this additional language, using actions and pictures. Only when pupils have some oral understanding of the additional language can they be expected to use it for reading and writing.

The written code

Pupils need to understand how the letters on the page represent particular sounds and how they combine to communicate meaning in the form of words. This is why it is important for teachers to give some attention to ‘phonics’ – the letters that represent particular sounds – when working with beginner readers. To take an example from English, you could use a picture of a dog, with the separate letters d o g and then the word dog underneath it. First ask pupils what they see in the picture (a dog), then point to each letter and pronounce it; then pronounce the whole word. Then check pupils’ understanding by pointing to the separate letters and asking them to make each sound. Next, ask them to tell you other words beginning with the d sound. Also give them some examples of your own.

The rules of writing

Pupils need to understand how words combine to make meaning in sentences, paragraphs and longer texts (e.g. a whole storybook) and how texts are written in different ways for different purposes (e.g. a recipe for cooking a meal is written differently from a story). In the early years, pupils begin learning about how writing is organised, but this is something that they learn more about all the way through their studies. Pupils need to work with whole texts so that they can see how words connect with one another and how a story or an argument develops. This is why phonics work alone is not sufficient.

How to read drawings, photographs and diagrams and how to make connections between these visual images and written words

Pupils need to be taught to notice details in drawings, photographs and diagrams. You can help them by asking questions such as ‘What is the old man holding?’ ‘What does the hippopotamus have on its back?’

About the world and how it works

The more that teachers help pupils to expand their general knowledge of the world and how it works, the easier it is for pupils to read about what is new and unfamiliar because they can make connections between what they have already experienced or learned and this new information.

Above all, it is important that pupils enjoy reading and writing – even when they find it challenging.

Resource 2: Examples of songs and rhymes

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Examples of Hausa and Yoruba songs with an English translation

These are lullabies –songs sung to help children to stop crying. Notice the frequent repetition of the same letters and sounds – particularly in the Hausa and Yoruba versions.

Hausa:

Yi shiru yaro, yaro yi shiru (Sing twice)

Uwarka ta na zuwa

Yi shiru yaro, yaro yi shiru

Yoruba:

Dake omo, omo mi dake (Sing twice)

Momo re nbo

Dake omo, omo mi dake

English:

Be quiet, child, my child be quiet (sing twice)

Your mother is coming

Be quiet, child, my child be quiet

A rhyme in English that is fun to say quickly

Yellow butter by Mary Ann Hoberman

Yellow butter purple jelly red jam black bread

Spread it thick

Say it quick

Yellow butter purple jelly red jam black bread

Spread it thicker

Say it quicker

Yellow butter purple jelly red jam black bread

Now repeat it

While you eat it

Yellow butter purple jelly red jam black bread

Don’t talk with your mouth full!

Taken from:Yellow butter – Traditional rhymes/songs; New Successful English, Grade 6, Reading Book, OxfordUniversity Press

An action rhyme

I’m a little teapot, short and stout

Here is my handle, here is my spout

When I get my steam up

Then I shout

Tip me over

Pour me out.

Song of the animal world – a song from the Congo

Note: This song is about movement and the sounds of the chorus represent the movement of the creatures.

NARRATOR: The fish goes

CHORUS: Hip!

NARRATOR: The bird goes

CHORUS: Viss!

NARRATOR: The monkey goes

CHORUS: Gnan!

FISH: I start to left,

I twist to the right.

I am the fish

That slips through the water,

That slides,

That twists,

That leaps!

NARRATOR: Everything lives,

Everything dances,

Everything sings.

CHORUS: Hip!

Viss!

Gnan!

BIRD: The bird flies away,

Flies, flies, flies,

Goes, returns, passes,

Climbs, floats, swoops.

I am the bird!

NARRATOR: Everything lives,

Everything dances,

Everything sings.

CHORUS: Hip!

Viss!

Gnan!

MONKEY: The monkey! From branch

to branch

Runs, hops, jumps,

With his wife and baby,

Mouth stuffed full, tail in air,

Here’s the monkey!

Here’s the monkey!

NARRATOR: Everything lives,

Everything dances,

Everything sings.

CHORUS: Hip!

Viss!

Gnan!

Taken from: Song of the animal world – Traditional song from the Congo, African Poetry for Schools, Longman

Resource 3: Example questions to ask about a grocery item

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

- What is in this tin/packet/box?

- How do you know this?

- Which word or words are in the biggest letters?

- Why do you think this word or these words are in the biggest letters?

- How many words begin with capital letters?

- Which words are written more then once on the package?

- Which word is used the most?

- What is the weight of this product (grammes/kilogrammes)?

- What do all the words and pictures tell you about this product?

Questions to encourage critical thinking

- Do you agree or disagree with what these words and pictures tell you?

- If you had the money, would you like to buy this product? Why, or why not?

Note 1: Some products have words in more than one language. If this is the case for some of the items that you are using, you could ask pupils which languages have been used and why they think these have been used.

Note 2: These example questions are quite general. There are many other questions you could ask. For example, if there are pictures of people on the product, are they male or female, young or old? Why are these particular people on the packet/tin/box?

What pupils could learn from working with grocery packaging

Beginner readers could use the words on the grocery package to gain confidence and skill in recognising the shape of upper and lower case (capital and small) letters of the alphabet and in linking the letter shapes to sounds.

By copying letters and words from the packaging, beginner writers could gain confidence and skill in writing these letters and words accurately.

More advanced readers could read the ‘messages’ on the packaging and think about what these mean. They could begin to become critical readers.

By working in groups to design some grocery packaging, pupils could benefit from each other’s ideas, learn what is involved in package design, use their imaginations and practise some writing and reading.

Some pupils find it difficult to speak to the class because they don’t know what to talk about. Having a design for a package to explain to the class gives pupils a subject to speak about.

Each group’s design gives the rest of the class some additional material to read.

You could make reading cards with letters/words that some pupils found difficult to read. Put a helpful picture on each card. Use these for individual or small group reading practice with these pupils at a suitable time.

Resource 4: Preparing for a community walk – during which pupils will notice environmental print

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Step 1: If your class is very large, you could ask some adults from the community to help you in walking with groups of pupils. If you do this, meet with these adults before the walk to explain what you would like them to do. They should know what questions you will be asking pupils and what examples of environmental print you want pupils to notice. They may also have some suggestions to give you.

Step 2: Plan the activity by walking through the area around your school. For some of you, this may be a village; for others, part of a busy city. (Note: If your school is in a very isolated place, you may need to work with community members to arrange transport for pupils to a place where they can see a range of environmental print.) Notice every example of environmental print you can draw pupils’ attention to and plan a route for you and the pupils to walk. The kinds of print and visual images will, of course, vary greatly from one neighbourhood to another but may include names (e.g. school, clinic, mosque, church, community hall, shop, river, street); signs (e.g. a STOP sign); advertisements on billboards or the walls of shops; community notices(e.g. election posters or notices about meetings or social or sports events).

Step 3:Prepare a list of questions for pupils to answer. These could include:

- What does this sign/name/advertisement tell us?

- Why do you think it has been placed here?

- What language is it written in?

- Why do you think it has been written in this language?

- What information do you get from the drawings or photographs that you see?

- Which signs are easy to read? Why?

- Which signs do you like? Why?

- How could you improve some of the signs?

- What other names/signs/advertisements/posters/notices would you like to have in this neighbourhood? Why would you like to have these?

Taken from: http://info.worldbank.org/ etools/ docs/ library/ 121361/ 703_samples.doc (Accessed 2008)

Section 2: Stimulating interest in reading stories

Key Focus Question: How can you stimulate pupils to want to read stories and books?

Keywords: shared reading; creative responses; silent reading; beginnings and endings; stimulating interest

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used shared reading of stories in your teaching to support developing readers;

- used activities that focus on alternative beginnings and endings to stimulate interest in reading;

- explored different ways to promote sustained silent reading (SSR) in your classroom.

Introduction

Pupils are more likely to learn how to read successfully if they enjoy reading and read as often as possible. If you asked your friends what they enjoy reading, their answers might vary from newspaper sports pages to recipes, romantic novels, detective stories or biographies – or they might not read much at all! Like your friends, different pupils may enjoy reading different kinds of texts. They will respond to what they read in different ways. Your task is to motivate all the pupils in your class to read successfully and to enjoy reading.

This section focuses on helping pupils to find pleasure in reading and responding to stories.

1. Reading aloud

The kinds of stories and story-reading activities that pupils enjoy are likely to vary according to their age and their knowledge of the language in which the stories are written. Younger pupils and pupils who are just beginning to learn an additional language enjoy having a good story read to them several times – particularly if they have opportunities to participate in the reading. By reading a story several times and by encouraging pupils to read parts of the story with you, you are helping them to become familiar with new words and to gain confidence as readers.

The focus of Activity 1 is preparing and teaching a shared reading lesson. The aims of this activity are to increase your confidence and skills as a reader and to get pupils ‘hooked on books’.

Case Study 1: Using childhood experiences of stories to prepare classroom activities

When Jane Dlomo thought about her childhood in the Eastern Cape of South Africa, she remembered how much she had enjoyed her grandmother’s stories. Two things stood out in her memory: firstly, how much she enjoyed hearing the same stories over and over again and secondly, how much she and her brothers and sisters enjoyed joining in with the stories. Sometimes her grandmother asked, ‘What do you think happened next?’ Sometimes she asked the children to perform actions.

Jane decided to make her reading lessons with Grade 4 pupils more like her grandmother’s story performances. She also decided to experiment with activities that would involve pupils in sharing the reading with her and with one another. When she told her colleague Thandi about her decision, Thandi suggested that they work together to find suitable storybooks, practise reading the stories aloud to each other and think of ways of involving the pupils in the reading. Both teachers found that sharing the preparation helped them to be more confident in the classroom (see Resource 1: Preparation for shared reading).

Key Resource: Using storytelling in the classroom gives further ideas.

Activity 1: Sharing the pleasures of a good storybook

Read Resource 1 and follow the steps below.

Prepare work on other tasks for some pupils to do while you do shared reading with a group of 15 to 20.

Establish any background knowledge about the topic of the story before reading it.

As you read, show pupils the illustrations and ask questions about them. Use your voice and actions to hold pupils’ attention.

Invite pupils to join in the reading by repeating particular words or sentences that you have written on the chalkboard and by performing actions.

At the end, discuss the story with your pupils. (See Resource 2: Questions to use with book readings.)

How did you feel about your reading of the story?

Did pupils enjoy the story? How do you know?

What can you do to develop your story reading skills?

2. Using writing to encourage reading

The child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim (1976) believes that if children find ‘magic’ in stories, they will really want to learn to read. He argues that if a child believes strongly that being able to read will open up a world of wonderful experiences and understanding, they will make a greater effort to learn to read and will keep on reading.

Sharing interesting stories with pupils is one way for a teacher to make reading a magical experience. Stimulating curiosity and imagination by encouraging them to create alternative endings (and sometimes beginnings) to stories and to share these with their classmates is another. Case Study 2 and Activity 2 describe how you can help your pupils to become story makers for one another.

Case Study 2: Reading stories; writing new story endings

Mrs Anthonia Jatau teaches English to Primary 6 in a Kaduna school. One day, she asked her pupils to think about the stories they had read with her and to tell her which story ending they liked best and which they found disappointing or unsatisfactory. She found they had different favourite stories. However, there was one story that most pupils didn’t like because they didn’t know what happened to three characters that ‘disappeared’ from it. Anthonia asked them to suggest what could have happened to these characters and wrote their ideas on the chalkboard. Then she asked pupils to choose one of the three characters and to write an ending to this character’s part in the story. She encouraged pupils to use their own ideas, as well as those from the chalkboard, and to include drawings with their writing. Then she reread the story to remind them of the setting, the characters and the main events.

Although Anthonia asked pupils to write individually, she also encouraged them to help each other with ideas, vocabulary and spelling. She moved around the room while pupils were writing and drawing, helping where needed. She was very pleased to find that most of her pupils really liked the idea of being authors and of writing for a real audience (their classmates). She noticed that they were taking a great deal of care with their work because their classmates would be reading it. In the next lesson, when they read each other’s story endings, she observed that most of her ‘reluctant readers’ were keen to read what their classmates had written and see what they had drawn.

Activity 2: Writing new beginnings and endings to stories

Write on your chalkboard the short story in Resource 3: A story. Omit the title and the last two sentences.

Read the story with your pupils. Discuss any new words.

Ask them to answer questions such as those in Resource 3.

Organise the class to work in fours – two to write a beginning to the story and two to write an ending. Each pair does a drawing to illustrate their part of the story. (This may take more than one lesson.)

Ask each group to read their whole story to the class and to display their drawings. Discuss with pupils what they like about each other’s stories.

Finally, read the title and the last two sentences of the original story to your class. (They are likely to be surprised that it’s about soccer!)

Find another story to repeat the exercise.

How well did this activity work?

How did the pupils respond to each other’s stories?

3. Encouraging individual reading

Teachers should be good role models for pupils. Your pupils are likely to become more interested in reading if they see you reading. Try to make time each day (or at least three times a week if that is all you can manage) for you and your pupils to read silently in class. You can adapt this depending on the age and stage of your pupils. For example, young pupils could look at a picture book with a partner or listen to someone reading with them in small groups.

Extensive or sustained silent reading (SSR) helps pupils become used to reading independently and at their own pace (which may be faster or slower than some of their classmates). The focus is on the whole story (or on a whole chapter if the story is a very long one) and on pupils’ personal responses to what they read. SSR can be done with a class reader, with a number of different books that pupils have chosen from a classroom or school library, or with newspapers and magazines (if pupils can manage these) – see Resource 4: Sustained silent reading.

Case Study 3 and the Key Activity suggest ways to assess pupils’ progress as readers. (See also Key Resource Assessing earning.)

Case Study 3: Teachers’ experience of sustained silent reading

A workshop was organised by the Reading Association of Nigeria (RAN) in Abuja to introduce teachers to sustained silent reading (SSR). It was explained that one of the main aims of SSR is to create a ‘culture of reading’ among pupils.

Teachers were invited to participate in SSR and then to reflect on their experiences. Each teacher chose a book or magazine and read silently for 20 minutes. After this, they had ten minutes of discussion with three fellow readers about what they had read and how they responded to the text. When they returned their books and magazines, they signed their names in the book register and, next to their names, wrote a brief comment about the text.

These teachers decided that SSR is useful for developing concentration and self-discipline, for learning new vocabulary and new ideas and for providing content for discussions with other pupils. They thought their pupils would enjoy this activity and be proud when they finished reading a book. Some teachers decided to try this with a small group at a time and rotate around the class because they only had a few books in the class.

Key Activity: Sustained silent reading

Collect interesting books, magazines and stories that are at an appropriate level for your pupils. Involve pupils and community in collecting suitable texts or use books your pupils have made in class (see Resource 4).

Set aside 15–20 minutes every day or three times a week for sustained silent reading. Ask pupils to choose a text to read silently. Read yourself as they read.

At the end, if they have not finished their books, ask them to use bookmarks so they can easily find their places next time.

Ask each pupil to make or contribute to a reading record (see Resource 4).

Every week, ask pupils, in small groups, to tell each other about what they have been reading.

Move round the groups to listen to what pupils are saying. Check their reading records.

Do pupils enjoy this activity and are they making progress with their reading?

Resource 1: Preparation for shared reading

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Choose a story with characters and events that you think will interest your pupils.

Think about any background knowledge that pupils will need in order to understand and enjoy the story. Decide how to provide this before you begin the story reading. For example, young pupils in some parts of Africa would be familiar with a hippopotamus, but in others they may not be, so before reading the story Hot Hippo you would need to find out what pupils know by asking questions like these:

Questions to establish background knowledge

- What does a hippopotamus look like?

- Would you be frightened of a hippopotamus? Why, or why not?

- Where would you be likely to see one?

- What does a hippopotamus eat?

First prediction question

- This story is called Hot Hippo. Look at the drawing on the cover. (The drawing shows a hippopotamus trying to shelter under some palm leaves.) What do you think the story will be about?

Taken from: http://www.dixie.fcps.net/ Book_Jackets/ hothippo.gif (Accessed 2008)

Note: While these questions refer to the story Hot Hippo, similar questions could be asked about animals, people, places or activities in relation to any story.

Practise reading the story aloud before you use it in your classroom. Think about how to perform the voices of the characters and about the actions you can use to make the story come alive. If there are drawings with the story, decide how to use these when you read to your class.

Look for parts of the story where pupils can join in once they are familiar with the story. For example, in one story, Eddie the elephant tries to copy the actions of other animals or the actions of people and every time he fails he cries ‘Wah! Wah! Wah! Boo! Hoo! Hoo! I wish I knew what I could do!’ You could write a chorus like this on your chalkboard for pupils to follow.

Look out for places in the story where you could ask pupils some prediction questions, such as: ‘What do you think Eddie will do next?’ or ‘How could the Hot Hippo solve his problem?’

Resource 2: Questions to use with book readings – first, second and third readings

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Here are a few questions you could ask before reading a story with pupils and then examples of questions to ask when the reading has been completed. There are also questions after they have read the book another time or more.

FIRST READING SESSION Before reading

During reading

After reading

|

SECOND AND THIRD READING SESSIONS (Note: These should be some weeks apart.) Before reading

During reading Again, ask questions about the development of the story and how the words and pictures contribute to this development. After reading

Having read the book more than once, would you recommend that other pupils read it more than once with their teacher? |

Taken from: Swain, C. The Primary English Magazine

Resource 3: A story

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Write this story on the chalkboard, but do not write either the title or the last two sentences (‘He shot – low to the right. What a goal!’) on the board until the very last part of your lesson.

[Run for glory by Mark Northcroft (aged 12 years)]

On and on he ran. His legs felt like churning acid. He could hear his pursuers closing in on him. He felt he could not keep this up much longer but he knew he had to. The footsteps were gaining on him. ‘Faster! Faster!’ he cried. ‘I can’t! I can’t!’ he answered. Somewhere deep inside himself, he found a sudden surge of energy. Now he knew he could do it.

Suddenly a man approached him from out of nowhere. ‘Now or never,’ he thought.

[He shot – low to the right. What a goal!]

Notes

‘His legs felt like churning acid’ – This simile or comparison is not easy to explain but you could say that the man or boy felt pain in his legs as though he had a mixture of chemicals bubbling up in them.

‘pursuers’ – people who are following or chasing someone.

‘surge’ – a sudden, powerful movement.

‘energy’ – liveliness, capacity for activity.

Questions to ask pupils in preparation for writing an alternative beginning and ending to this story

- Who do you think ‘he’ is?

- Where do you think he is?

- What do you think is happening to him?

- Who is ‘a man’?

- What other people might be part of this story?

- What might have happened before this part of the story?

- What might happen next?

Resource 4: Sustained silent reading

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Developing sustained silent reading (SSR) in your classroom is important in encouraging your pupils to want to read and developing their reading skills. For SSR to succeed requires some careful planning ahead. You will need to gather together resources for your class or a group to read. These could be articles from newspapers or magazines, books, etc. You need to be resourceful to gather these and also to store them so they are not lost or damaged.

If you have enough resources for your whole class, you could do SSR once a week at the start or end of the day. If you only have a limited number of resources, you could do it with one group each day and also work with your class to make more class books to read.

Questions to ask

- These are examples of questions that could be asked about many different kinds and levels of storybooks, but you may prefer to ask pupils for just a brief comment.

- What happens in the first part (introduction, beginning) of the story?

- What happens in the middle part (where there are complications or conflicts in the story)?

- What happens at the end (resolution)?

- Is there a problem that needs to be solved?

- What is the goal of the main character or characters?

- What happens to the characters in the different parts of the story? What difficulties do they face?

- Have similar things ever happened to you?

- If their first attempt is unsuccessful, do the main characters get another chance to achieve their goal?

- What happens to the characters at the end?

- How do you feel about this story? Did it make you think about your own life or anyone else’s? If so, in what way(s)?

Keeping a reading record

As pupils carry out SSR it is useful for them to keep records of the books they have read and to comment on what they did or did not like about them. It is also a way of seeing what breadth of material they are reading and the kinds of things that interest them. It tells you how much they are reading, especially if you encourage them to also include books, newspapers, magazines, etc. that they read at home or elsewhere. With newspapers and magazines, you may suggest they only add these when they read them regularly and say how often they read them. They may want to include articles from particular magazines.

Keeping a record must not become a bore, as this will put pupils off reading. Each record should only include the title and author and maybe publisher if you wish to add the book to the class collection (if you have a budget). The pupil could say if they liked the book and why, and if they’d recommend it to others to read.

The record could be a class one, where the title of each book in the library is on the top of a sheet of paper and every time someone reads this book they sign the list and put in a short comment. Another way is for each pupil to have a page at the back of an exercise book where they keep a list of the books they have read and every time they finish a book or give up on a book they make a comment next to the title and author. It would be useful if these entries are dated, so you can see how often they are finishing a book etc.

Here is an example of a reading record form you could use.

| My reading record

Name……………………………………….. Class…………………………….. |

| Text | Author | Date started | Date finished | Comments |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

Book report form adapted from: Programming and strategies book http://www.schools.nsw.edu.au/ media/ downloads/ schoolsweb/ studentsupport/ programs/ lrngdificulties/ pshandbook.pdf (Accessed 22/06/07)

Smileys from http://www.wpclipart.com/ smiley/ index.html (Accessed 22/06/07)

Book image from Microsoft clip art accessed 22/06/07

Collecting and displaying materials for SSR

If you need to start your own classroom library, the first requirement is to collect books and magazines. There are organisations that can help schools obtain books. Here are some useful contacts.

Nigeria Book Foundation P.O. 1132 Awka Anambra State Nigeria +234 46 551403 +234 46 552615 email: nbkfound@inforweb.abs.net

Reading Association of Nigeria (RAN) Dr Obiajulu Emejulu RAN President Directorate of General Studies Federal University of Owerri Imo State, Nigeria email: omejulus@yahoo.com

Zonal Co-ordinators:

South East – Dr Gabriel Egbe, Department of General Studies, Cross Rivers State University of Technology, Calabar; email: egbe2004@yahoo.com

South West – Dr Nkechi Christopher, Department of Communication and Language Arts, University of Ibadan, Ibadan; email: nmxtopher@gmail.com

North East – Dr Chinwe Muodumogu, Department of Curriculum and Teaching, Benue State University, Makurdi; email: chitonia90@yahoo.com

North West – Dr Sule Eguare, Department of English, Uthman Dan Fodiyo University, Sokoto; email: sule.egua@yahoo.com

For more information on SSR, the following website is also useful:

http://www.trelease-on-reading.com

Sometimes the embassies of foreign countries or organisations linked to embassies, such as the British Council, are able to make donations of books. Service organisations such as Rotary Clubs also collect and donate books. If you cannot contact any organisation for assistance, then try asking colleagues and friends to donate books and magazines that their children or other family members have finished with. Some schools ask parents to help teachers to organise fundraising events and then they use the money that is raised to buy books. Key Resource: Being a resourceful teacher in challenging circumstances explores this further.

Once you have enough books and magazines for all the pupils in your class to read individually, you need to think about how to look after these precious materials. If you have, or could make (or get someone else to make), some shelves for one side or the back of your classroom, you could then display the books and magazines in order to attract pupils’ interest. In an exercise book, write down the titles of the books and magazines so that you can keep track of them.

At the end of each SSR period, watch carefully to check that pupils return the books to the shelf.

If you do not have shelves, then pack the books and magazines carefully into boxes. You may like to choose some pupils to be book monitors to help you distribute books from the boxes at the beginning of the reading period and to pack them away at the end.

Section 3: Ways of reading and responding to information texts

Key Focus Question: How can you develop your questioning skills to help pupils use information texts effectively?

Keywords: information texts; comprehension; summary; questions; assessment

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- developed your ability to create questions and tasks that encourage close reading of texts and personal responses;

- explored ways to teach pupils how to read and write about information presented in different forms;

- helped your pupils develop the skills needed to summarise texts;

- used these strategies to assess learning.

Introduction

In ‘the information age’ we all need to be able to read and respond to information presented in many different forms. Reading information from a chart or diagram requires different skills from reading a story.

As a teacher, your role is to help pupils understand what they read, summarise the main ideas in a text and respond with their own ideas. While it is important for pupils to be able to write answers to questions on what they have read, some will produce better work if they have opportunities to demonstrate what they understand through other activities, e.g. making posters or pie charts.

This section suggests ways to help pupils develop their comprehension and summarising skills.

1. Reading for understanding

Comprehension exercises are very common, but how well do they extend pupils’ reading skills?

Case Study 1 demonstrates that you need to think very carefully about whether the ‘reading comprehension’ questions in textbooks really help you to know what pupils have understood from their reading. You need to create questions or activities that require pupils to read information texts carefully. Activity 1 gives you some examples to try out and use as models when designing your own questions and activities. Key Resource: Using questioning to promote thinking gives further ideas.

Case Study 1: Rethinking ‘reading comprehension’

At a workshop in Lusaka, Zambia, teachers of English as an additional language read a nonsense text and answered questions on it. The first sentence in this text was: ‘Some glibbericks were ogging blops onto a mung’ and the first ‘comprehension’ question was ‘Who were ogging blops onto a mung?’ Every teacher knew that the answer was ‘some glibbericks’. In their discussion, they realised they could give the ‘correct’ answer because they knew that in English, ‘some glibbericks’ was the subject of this sentence. They didn’t need to know who or what a glibberick was, in order to give the answer!

After the discussion, they worked in small groups to design questions and tasks that would show them whether or not pupils had understood the texts on which these questions and tasks were based. They learned that questions should not allow pupils to just copy information from one sentence in the text. They designed tasks in which pupils had to complete a table, design a poster or make notes to use in a debate as ways of showing what they had learned from reading a text.

They reflected that the questions they asked and the tasks they set meant they could better assess their pupils’ understanding.

Activity 1: Comprehending and responding to information texts

- Read Resource 1: Text on litter. Make copies of the article and tasks or write the paragraphs and tasks on your chalkboard.

- Cover them over.

- Before pupils read the article, ask some introductory questions. Your questions should help pupils to connect what they already know to the new information in the article (see Resource 2: Introductory questions). If your pupils are young or you need to read the text to them, you could write their answers on the board.

- Next, uncover the article and tasks, and ask pupils to read the article in silence and write answers to the tasks. When they have finished, collect their books and assess their answers.

- Return the books and/or give the whole class oral feedback on what they did well and discuss any difficulties they experienced. (See Resource 1 for suggested answers to the tasks.)

In the next lesson, ask pupils to work in small groups to design an ‘anti-litter’ poster and display it in class (see Resource 3: Good posters).

2. Reading charts and diagrams

Think about all the kinds of information texts that you read. Whether these are in the pages of textbooks, in advertising leaflets or on computer screens, they frequently include diagrams, charts, graphs, drawings, photographs or maps. To be successful as readers, you and your pupils need to understand how words, figures and visual images (such as photographs or drawings) work together to present information. Many writers on education now stress the importance of visual literacy. Learning how to read and respond to photographs and drawings is one part of becoming visually literate. Reading and responding to charts, graphs and diagrams is another. Bar and pie charts are some of the easier charts to understand and to make in order to summarise information.

Case Study 2: Making a pie chart to represent the number of pupil birthdays in each month of the year

Miss Maria Bako likes to make each pupil in her Primary 6 class of 60 pupils feel special. In her classroom she has a large sheet of paper with the month and day of each pupil’s birthday. On each birthday, the pupils sing Happy Birthday to their classmate. One day, a pupil commented that in some months they sing the birthday song much more often than others. Maria decided to use this comment to do some numeracy and some visual literacy work on pie charts.

First, she wrote the names of the months on her chalkboard and then she asked pupils to tell her how many of them had birthdays in each month. She wrote the number next to the month (e.g. January 5; February 3, and so on).

Then she drew a large circle on the board and told pupils to imagine that this was a pie and that as there were 60 in the class there would be 60 sections in the pie, one for each pupil. The sections would join to make slices. There would be 12 slices, because there are 12 months in a year. Each slice would represent the number of pupils who had their birthday in a particular month, but each slice would be a different size. She began with the month with most birthdays – September. In September, 12 pupils had birthdays.

Pupils quickly got the idea of making 12 slices of different sizes within the circle to represent the number of birthdays in each month as a percentage of the class. They copied the birthday pie chart into their books and made each slice a different colour.

The class talked about other information they could put into a pie chart and decided to explore how many pupils played different sports, how many supported each team in the national soccer league and how many pupils spoke the different languages used in their area.

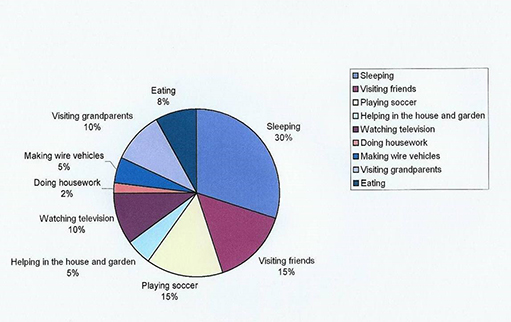

Activity 2: Comprehending and making a pie chart

Copy the pie chart in Resource 4: A pie chart onto your chalkboard.

- Ask pupils to suggest why this is called a pie chart.

- Write out the questions (part b) about the pie chart on your chalkboard and ask pupils to work in pairs to answer them.

- Discuss the answers with the class.

- Use your chalkboard to show pupils how to turn these answers into a paragraph about Iredia’s weekend. Ask pupils to draw the pie chart.

- For homework, ask pupils to draw their own pie charts to show how they usually spend their time at weekends.

- After checking the homework, ask pupils to exchange their chart with a partner and to write a paragraph about their partner’s weekend.

- What have you learned from these activities?

What relevant activity could you do next? (Look at Resource 4 for some ideas.)

3. Learning how to summarise

Learning to find and summarise the main ideas in the chapters of textbooks and other study materials becomes increasingly important as pupils move up through the school. These skills take practice to acquire.

The Key Activity and Resource 5: Text on the baobab give examples of ways to help pupils learn how to summarise information texts. You will need to do such activities many times. For older pupils, you could ask colleagues to show you what the pupils you teach are required to read in other subjects such as social studies or science. You could then use passages from social studies or science textbooks for summary work in the language classroom by following the steps in the Key Activity.

Case Study 3: Summarising key points from textbook chapters

The pupils in Mal Adamu Jibo’s Primary 6 class were anxious about the forthcoming examinations. They told him they didn’t really understand what their teachers meant when they told the pupils to ‘revise’ the chapters in their textbooks. Adamu decided to use an information text from their English textbook to give his class some ideas about how to find and write down the main points in a text.

He asked his pupils to tell him the purpose of the table of contents, chapter headings and sub-headings in their textbooks. It was clear from their silence that many pupils had not thought about this. A few were able to say that these give readers clues about the main topics in the book. Adamu told the pupils that in order to revise a chapter, they should write the sub-headings on paper, leaving several lines between each one. Then they should read what was written in the textbook under one sub-heading, close their books and try to write down the key points of what they had just read.

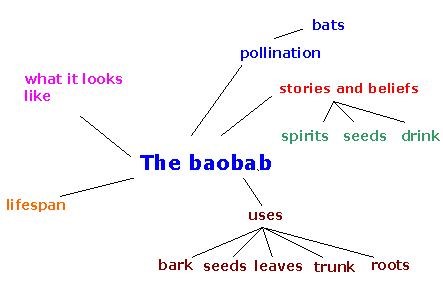

Next, they should check their written notes against the book and make changes to their notes by adding anything important they had left out or crossing out anything they had written incorrectly. Adamu said that some pupils prefer to make notes in the form of a mind map in which there are connections between important points. (See Resource 5and Key Resource: Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas.) He showed them how to do this.

Finally, he reminded them to ask their teachers to explain anything they had not understood. Adamu also told them how he made notes of what he found out about his pupils and their learning to help him plan more lessons.

Key Activity: Developing summarising skills

Before the lesson, copy the text from Resource 5 on the baobab tree or write it on your chalkboard. Try out the activities yourself first.

- Showing pupils some newspaper and magazine pages, ask why the articles have headlines and what they tell the reader. Ask them to suggest why their textbooks have headings and sub-headings.

- Ask pupils to read the information text about the baobab tree and to work in pairs to decide which paragraphs are on the same topic.

- Ask them to write a heading that summarises the paragraph(s) on each topic.

- Ask some pupils to read out their headings and write these on the chalkboard.

- Agree which are the best headings for each set of paragraphs on the same topic.

- Leave the ‘best’ headings on the board with some space under each one. Ask pupils to suggest key points from the paragraphs and record these.

- Show pupils how to link headings and key points in a mind map to help them remember about baobab trees.

If you have time or prefer to use a shorter text, you do the same activities with your pupils using the text in Resource 6: On the Kapok tree. Think about what pupils did well and what they found difficult and plan another session to deal with these.

Resource 1: Text on litter

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Litter

Litter is any kind of ‘left-over’ or waste product that people do not put in its proper place, such as a rubbish bin. People who simply drop waste such as fruit peel or empty cans on the ground are guilty of littering. We sometimes call these people litter bugs.

Litter does not just happen

People are responsible for litter. An item of waste, such as the wrapping from a bar of chocolate, is not litter if it has been placed in a rubbish bin. It becomes litter when someone drops it on the ground, leaves it lying on the ground where he or she has been sitting or throws it out of a window.

Litter can be dangerous to people

Broken glass and sharp rusty cans that are left in places where people walk – and especially where young children play – can cut them. These cuts can lead to serious infections. Fruit and vegetable waste is sometimes slippery and if people step on it they may fall and break an arm or a leg. Litter can be a cause of road accidents when drivers try to move their cars or trucks out of the way of sharp objects that could cut their tyres. Plastic bags and pieces of cardboard sometimes blow onto the windscreens of vehicles and stop drivers from seeing clearly.

Litter can be dangerous to animals and birds

Glass and cans may also cut the feet or mouths of domestic or wild animals while they are grazing. Nylon fishing line that is thrown on the ground or into water can get wrapped around the beaks or legs of birds and cause them to die because they can no longer move or eat. Sea creatures, such as seals and sharks, may get caught up in old fishing nets. If they cannot free themselves they will also die.

The dangers of plastic

Plastic litter causes problems for fish, birds and people. In rivers and the sea it can be harmful to fish because they can get caught up in it and not break free. Plastic bags on beaches have led to the deaths of many seagulls. Even loosely woven bags, which vegetables and fruit are sometimes packaged in, can be harmful to birds. They get inside these and cannot find a way out, as the material is very tough. Pieces of plastic or plastic bags can get caught in the outboard motors of boats and can cause the motor to stop working.

If we want to keep our country clean and beautiful and to protect our people and our wildlife, we must not throw litter. It is not difficult to throw a can, bottle, plastic bag or piece of paper into a bin rather than on to the ground.

Writing tasks based on Litter

- List seven kinds of litter that are mentioned in the article. (To answer this question successfully pupils need to find information in several different paragraphs, so they have to read carefully.)

- Explain what the word litter means. (Pupils could copy an answer from the first paragraph of the text without really understanding what the word means but the next question can help you to check their understanding because you are asking them to use a word or words from other languages that they know – for many pupils their home language.)

- What is the word (or words) for litter in any other languages that you know?

- List three kinds of litter that are harmful to birds. (Birds are mentioned several times in the passage, not just in the paragraph with the heading that includes birds. Pupils need to find each reference to birds and then link this to different types of litter and the problems these cause.)

- In your own words, describe three of the ways in which people can be harmed by litter. (Pupils should use the sub-heading to guide them and then try to express the content of the paragraph in their own words rather than just copying from the paragraph. This will help you to see if they have understood what they have read.)

- Do you agree with the writer that it is not difficult to throw waste into a rubbish bin? Give a reason for your answer. (This is a personal response question that encourages pupils to think critically and express their own ideas.)

- Suggest what else can be done with waste products such as glass, paper, plastic, fruit and vegetable peels. (This is also a personal response question and encourages class discussion about the environmental topic of recycling.)

Notice that the answers to questions 1 to 5 require pupils to read the text carefully whereas questions 6 and 7 require them to use their own ideas.

Answers to the writing tasks

- Fruit and vegetable peel, glass, cans, plastic, fishing line, paper, cardboard.

- Litter is waste material that people do not put in its proper place (such as a rubbish bin).

- Words from languages used in your class.

- Nylon fishing line, plastic bags, woven fruit and vegetable bags.

- People can cut themselves on broken glass or sharp cans. People can slip on fruit or vegetable waste and break an arm or leg. People can be involved in road accidents when drivers try to avoid litter in the road or when they can’t see because of litter blown onto the windscreen. People on water in motorboats may not be able to safely reach land if the motor of the boat is damaged by plastic. (Four ways are mentioned here.)

- This is a question to which pupils should be encouraged to give a variety of responses. For example, it is not possible to put waste in a rubbish bin if there are no bins in the school grounds or in the streets.

- This task gives you and the pupils an opportunity to discuss various forms of recycling. For example, vegetable and fruit peels can be put into a compost heap or dug straight into garden soil in order to enrich the soil. Plastic strips can be woven into useful mats for the floor. In some towns and cities, glass, cans and paper or cardboard can be taken to recycling facilities and people can even be paid for what they collect and bring to these places.

Taken from:Taitz, L. et al, New Successful English, Learner’s Book, OxfordUniversity Press (Accessed 2008)

Resource 2: Introductory questions

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Ask these questions before reading starts in order to help pupils make connections between what they already know and what they are going to read about in the information text on litter.

- Are there any kinds of rubbish in our school grounds or around our homes? If there are, what kinds?

- How did the rubbish get there?

- If there is no rubbish, what is the reason for the clean areas around our school grounds or homes?

- What is another word for rubbish that lies on the ground in our school yard or street? (If pupils don’t know, point to ‘Litter’ on the chalkboard or in their copy of the article.)

- What are some of the problems that litter can cause?

Resource 3: Good posters

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Features of good posters

- The whole sheet of paper is used.

- Words are in large print.

- Often the words are not whole sentences.

- Pictures should be simple, clear and powerful.

- The colour of the words and pictures should attract attention.

- The position of the words and the pictures on the sheet of paper should attract attention. (This is called the ‘layout’ of the poster.)

Steps to follow for lessons on designing and presenting posters and what pupils can learn from this activity

Tell pupils that they are going to work in groups to design an ‘anti-litter’ poster.

Begin with a whole-class discussion. What makes a good poster? What messages would be suitable for posters that encourage people to stop littering?

Give each group a large sheet of paper or card and make sure they have pencils and pens.

While the groups are working, move round the class to help where necessary and to take note of what pupils are learning.

When groups have finished, ask each group to show their poster to the class and to talk about why they designed it in a particular way.

Display the posters in your classroom or elsewhere in the school.

Pupils can demonstrate that they are learning:

- how to work cooperatively in a small group;

- how to design a poster;

- new vocabulary;

- what kinds of litter there are (by understanding information from the passage and by using their own experience);

- what can be done to prevent littering;

- how to talk about their posters.

- Which kinds of learning have your pupils demonstrated?

How do you know this?

Where do they still need to improve?

How will you help them?

Resource 4: A pie chart

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

a) A pie chart: How Iredia spends his time at weekends

Basic information

30% sleeping;

15% visiting friends;

15% playing soccer;

5% helping in the house and garden;

10% watching television;

2% doing homework;

5% making wire vehicles;

10% visiting grandparents;

8% eating.

b) Questions on the pie chart

- What does the pie chart tell us? (How Iredia spends his time at weekends.)

- What does Iredia spend the most time doing? (Sleeping.)

- What does he spend the least time doing? (Homework.)

- What does he do for the same amount of time as he watches television? (Visits grandparents.)

- What does he do for the same amount of time as helping in the house and garden? (Making wire vehicles.)

- When he is awake, what two things does Iredia spend the most time doing? (Visiting friends and playing soccer.)

- If you made a pie chart to show how you spend your weekend, would it be similar to Iredia’s or different? (Many possible answers.)

- You could help pupils write about their partner’s weekend by designing a writing frame with them, or by agreeing an example paragraph together. Here are examples for use to use or adapt.

Writing frame for describing a partner’s weekend X’s weekends X likes/doesn’t like weekends… He/she spends the greatest part of the weekend… He/she usually… and sometimes… On Saturday mornings… On Saturday afternoons… On Saturday evenings… On Sunday mornings… On Sunday afternoons… On Sunday evenings… |

c) Paragraph about Iredia’s weekends

Iredia loves weekends. He enjoys staying in his warm bed much later than on school mornings and taking his time over meals with the family. He spends the biggest part of his weekend visiting friends and playing soccer. He usually watches television with his family in the evenings and sometimes stays up very late to do this. On Saturday mornings he and his sisters help their parents with cleaning the house or working in the garden. After they have finished, his sisters like to go to the shops but Iredia either goes to his friends or spends some time making wire cars and trucks that he and his friends can race. Sometimes he takes his cars and trucks to show his grandparents when he visits them on Sundays. Usually he needs to find some time on Sunday evening to do his homework for Monday.

Some of the information in this paragraph cannot be gleaned from the chart. The author has made up bits based on their experience and the data given. You may wish to explore this with your pupils. Ask them what they can say from the chart and which parts are made up.

d) What you and your pupils can learn from these activities

- To read information on a pie chart.

- To compare one item of information on the chart with another.

- To make a pie chart in order to summarise information.

- To understand that the same information can be presented in different ways.

- To use information from a pie chart to write a paragraph.

- To learn ‘time expressions’ (e.g. ‘usually’, ‘sometimes’).

e) Ideas for further activities

To consolidate pupils’ learning about pie charts, they could make another one – perhaps about class birthdays or about sports teams they support or languages they speak. You could also decide to show them other ways of representing information such as a bar graph or a table if you have information about these. Your colleagues may be able to assist you here.

Resource 5: Text on the Baobab

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Before starting the Key Activity, you may wish to use Resource 1 as an example and discuss with your pupils how sub-headings can summarise key points.

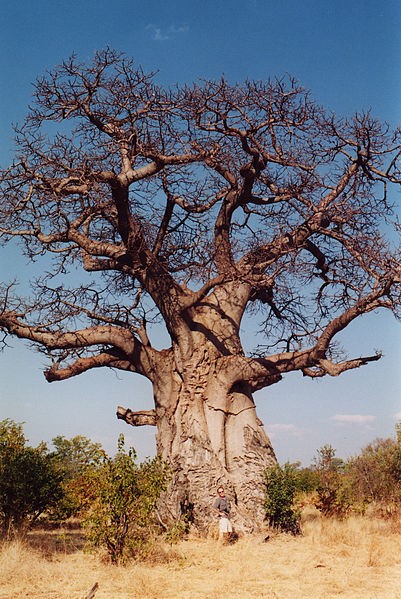

The Baobab

The baobab is a very unusual tree. Some people think it is ugly because it is fat and for much of the year it has no leaves. It does not even seem to grow the right way up. In fact, some people who live in the land of the baobab say that it grows upside down with its branches in the earth and its roots in the air.

The baobab does things differently from other trees. Most trees use bees and birds to carry pollen grains from one tree to another so that the trees can be fertilised and make new flowers, fruit or nuts. The baobab uses bats. In early summer this tree produces big flowers with white petals. The flowers only open at night when the bats appear. The bats suck the nectar and transport the pollen from one tree to another on their wings and bodies.

Baobabs live for a very long time. Some of the largest baobabs may be over 3,000 years old.

The tree has many uses. In the past, some of the Khoi and San people of southern Africa used baobabs for their homes. They set fire to the soft insides of the trunk, making a hole big enough to live in. Even with this big hole in the trunk, the tree continued to live.

The bark of the tree has a number of uses. It can be used for making soft floor mats, paper and thread. The fibres of the bark make very strong rope.

Other parts of the tree also have their uses. If the roots are mashed, they make a soft porridge. The soft insides of the tree provide moisture for thirsty animals during the dry season. If the seeds are soaked in water for a few days, they produce a medicine that is very good for fevers. If the seeds are dried and ground up, they make a good but rather bitter coffee. If the leaves are boiled they become like cabbage and can be eaten.

There are many stories about the baobab. The people in Venda in southern Africa say that the trees were once the hiding place for evil spirits. Then a kind god came and tore the trees out of the ground and replanted them upside down. As a result, the evil spirits could no longer hide in the trees.

Other people believe that if you suck the seeds you will be safe from crocodiles, and if you drink a drink made from the bark you will grow to be big and powerful.

The baobab is a truly amazing tree. It is one of the marvels of Africa.

Suggested sub-headings for The Baobab text

Paragraph 1: What a baobab looks like

Paragraph 2: How pollen is transported between baobab trees

Paragraph 3: Lifespan

Paragraphs 4, 5, 6: Uses of the baobab

Paragraphs 7, 8: Stories and beliefs about baobabs

Note: There is no new information in the final paragraph. It provides a comment from the author, giving his or her opinion of this tree.

A mind map summary of The Baobab

Taken from: Ellis, R. & Murray, S. Let’s Use English, Learners’ Book 5 (Accessed 2008)

Resource 6: The kapok tree

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Picture of kapok tree from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceiba_pentandra (Accessed 2008)

The kapok tree is a tropical tree which is common in parts of South America, the Caribbean, and tropical West Africa. You can find the kapok in the Capital Territory region around Abuja.

The tree can grow up to 70 metres (230 feet) tall, and the trunk can be up to 3 metres (10 feet) in diameter. The trunk and many of the larger branches have large, strong thorns on them. The leaves come in groups of 5 to 9 at a time, and they can be up to 20 centimetres long. The flowers on the leaves can produce well over 200 litres of nectar per tree in a season. This is why bats like the tree so much. They sometimes travel as much as 12 miles between trees to drink the sweet nectar. The adult trees produce several hundred 15 centimetre seed pods. A fluffy yellow or white fibre surrounds the seeds. This fibre is also called kapok. The kapok fibre is light, burns easily, but does not absorb water easily. It is used as filling for mattresses, pillows and cushions. The seeds can be used to make soap or fertiliser for crops.

Text Taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/ Ceiba_pentandra

|  |

|---|

Pictures of kapok seed pod and fibre

Taken from:http://www.thailex.info/ THAILEX/ THAILEXENG/ LEXICON/ kapok.htm

Both sites accessed on 23/06/07

Section 4: Ways of presenting your point of view

Key Focus Question: How can you help pupils become confident and thoughtful presenters of ideas?

Keywords: own feelings; viewpoints; debate; letter; newspaper; inclusion

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- supported pupils in expressing their points of view in speech and in writing;

- Developed your ability to help pupils understand other people’s situations, feelings and points of view;

Introduction

This section focuses on ways we express feelings and present points of view. It is important that teachers and pupils are able to do this with confidence, both in speech and in writing, in order to participate in decision-making in the family, school and wider community. As a teacher, you have an important role to play. You need to be able to argue your case within the school for such things as resources and ways of working, and also you need to support your pupils as they develop these skills.

It is important that all pupils feel included in the classroom and community, regardless of their state of health, home circumstances or any disability.

1. Using writing to elicit childrens’ feelings

This part explores ways of working that will allow pupils to express their feelings and explore ideas about many things, including their personal lives. It looks at how to manage conflicts and frustrations more effectively.

Often, when starting topics that touch on sensitive issues, it is helpful to let pupils explore their ideas privately first. Writing thoughts down around an issue can help to stimulate thinking. This is a technique that can also be applied to other topics to find out what pupils already know.

Case Study 1: Writing to express feelings and point of view

Ms Vivian Mbaya in Lagos, Nigeria, discussed with her junior secondary pupils the kinds of things that make children feel different and/or left out.

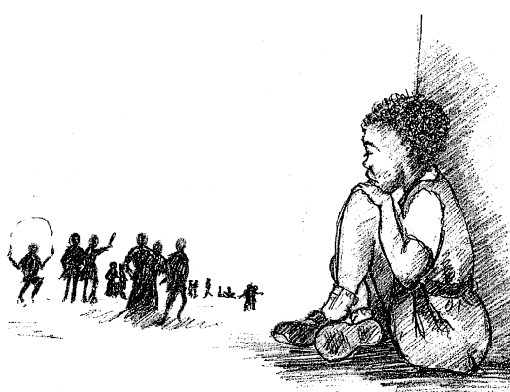

Next, she asked them to look at a picture of a child sitting alone while others played (Resource 1: Child who is ‘left out’), and asked them to write about this child. She also asked them if they had ever felt left out or different from others in the past, or if they were feeling this way at present. She asked them to write about these feelings.

Then they played games that helped them to experience what it was like to have a physical disability (see Resource 2: Games that promote understanding of physical disability). Afterwards, they talked about how such disabilities may make children feel different and sometimes cause them to be rejected by their classmates. They also talked about children who suffered from HIV/AIDS, or whose parents had died from that disease. Vivian asked them to write about their experiences during the games. What did it feel like to have a disability?

After this, before starting a sensitive topic, Vivian often asked her pupils to write or talk in pairs or small groups to explore their own ideas first.

Activity 1: Writing to express ideas and feelings

When starting a sensitive topic with pupils it is useful to explore their ideas and feelings first.

- Select a picture, poem or story to stimulate their thinking (see Resource 1 for one example).

- Show the picture/read the poem or story and ask them to think about what it means to them.

- Ask them to write or talk with their partner about their thoughts and include their feelings as well.

- Remind them that no one will mark this or judge what they say to each other. It is for them to think about what they think and feel at that moment.

- Next, discuss with the class what they think the messages are in the picture.

2. Organising a debate

Learning how to participate in a debate helps pupils (and adults) to express their points of view, listen to the views of others and think critically. When you choose topics for debate in your classroom, make sure you choose topics that are important to your pupils so they will really want to express their points of view.

In Activity 2 you will introduce your pupils to the rules and procedures for debating and support them as they prepare for a formal debate. In Case Study 2, the debate is on inclusion in the classroom. With younger children, you could hold very simple discussions or debates about issues such as not hitting each other.

Resource 3: Structure of debating speeches and Resource 4: Rules and procedures for debating will give you guidance. You may also find these rules and procedures useful if you belong to organisations that need to conduct debates.

Case Study 2: Preparing for and conducting a debate

After Vivian Mbaya and her pupils had written about being ‘left out’, they discussed specific children who were not in school for some reason. Some of these children were disabled, some had no parents and were heading households and some did not come to school because they were too poor to buy uniform.

Vivian introduced the idea of debating to the class, and presented the motion: ‘This class moves that all “out-of-school” youngsters, isolated because of barriers to learning, should be brought to school.’