Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 9:18 PM

Module 2: Investigating history

Section 1: Investigating family histories

Key Focus Question: How can you structure small-group activities in your classroom to develop collaborative working and build self-confidence?

Keywords: family; history; confidence; investigation; small-group work; discussion

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- structured your activities to help pupils understand themselves and their relationships with other family members;

- used small-group discussions to build pupils’ self-confidence as they investigate their family histories.

Introduction

Good teaching often starts by encouraging pupils to explore situations that they are already familiar with. In terms of history, this means using their own lives, and the lives of their immediate families, as a source of investigation. The skills used to explore this familiar history can then be used in the study of broader historical questions.

All of us have a history, which starts from the moment we are born. This will include all our experiences and all the people we interact with.

In this section, you start by exploring your pupils’ immediate family situations and their roles and responsibilities within the family. You will also look at the wider context of the extended family. As you work in this area, you will have to be sensitive to different backgrounds and family or other structures that your pupils live in.

1. Working in groups to discuss families

When investigating the family, it is useful to first explore pupils’ understanding of what a family is and show them the diversity among families. Celebrating such diversity helps pupils feel better about themselves when they realise how different families can be. Case Study 1 and Activity 1 explore different ways to do this.

In the case study, the teacher encourages his pupils to work in small groups (see Key Resource: Using group work in your classroom) and to remember the rules that they have agreed for small-group discussions.

Case Study 1: Using group work to explore my own family

Mr Nguzo is a social studies teacher at Muhimu Primary School in Tanzania. He wants his pupils in Standard 3 to learn about families and the roles of different family members.

He organises groups of not more than six; he puts pupils together who do not usually work with each other.

- In the groups, pupils take it in turns to answer the following questions, which he has written on the board.

- What is your name?

- Who are your father and mother? What are their names?

- Who are your grandfathers and grandmothers? What are their names?

- How many sisters and brothers do you have? What are their names? Are they older or younger than you?

- How many cousins do you have? What are their names?

- During the discussion, Mr Nguzo goes to each group to check that all the pupils are being given a chance to contribute. After 10 to 15 minutes, he asks the groups to share with the whole class what they have found out about different families: What were the similarities between the families? What were the differences? (For younger or less confident pupils, he would have to ask more structured questions, e.g. ‘Who had the most brothers?’)

- Then he asks the groups to consider this question:

- What makes someone your sister, your brother, your aunt, etc.?

- After 10 minutes, one member of each group presents their answers to question 6 to the class. Mr Nguzo prepares a large, basic kinship chart to help focus the discussion (see Resource 1: Kinship chart).

Mr Nguzo and the pupils note that although there are words in their language that express cousin, uncle and aunt, these relations are normally referred to as brother or sister; grandfather, father are usually simply father; grandmother, mother are similarly simply mother. There is a distinction between the uncles and aunts from the mother’s side and those from the father’s side. Mr Nguzo realises that teaching pupils about the relationships within families can be confusing for younger pupils.

Activity 1: Who am I?

- Before the lesson, prepare a kinship chart as a handout (see Resource 1).

- Ask the pupils to work in groups of three or four. One pupil volunteers to list all the people they know in their family and fill in the details on a kinship chart. (You may wish to select which pupil is chosen.)

- Pupils might want to draw pictures of their relatives on the chart.

- Share these charts with the class.

- Discuss the variation in families and emphasise how good this variety is.

At the end of the lesson, display the kinship charts on the wall of the classroom.

2. Modelling making a timeline

When studying past events, it is important to help pupils understand the passage of time and how things change from generation to generation.

Developing the ways that young pupils look at their family histories will help them link events together as well as put them in sequence. Resource 2: Another kinship chart provides a family tree that will help pupils see relationships between family members, e.g. their cousin is their mother’s or father’s sister’s or brother’s child.

Case Study 2: Family histories

Jumai Fataki plans to teach about family relations over time with her Primary 5 pupils.

She cuts a series of pictures from magazines of people of different ages, doing different things, e.g. at a wedding, a school prize day, and writes numbers on the back of each picture. She tells her pupils that the photographs represent different events in one person’s life and asks her pupils, in groups of six, to sequence the photos in terms of the age of the person. She gives them 15 minutes to discuss the order and then asks each group to feed back. She asks why they chose the order they did and lists the clues they found in the pictures to help them order the events. They discuss the key events shown in the pictures and Mrs Fataki tells the pupils they have made a ‘timeline’ of life.

Activity 2: Pupils creating their own timeline

- Resource 3: My timeline can be a starting point for your class to do their own timeline.

- First, discuss the importance of knowing one’s own origins and members of one’s family.

- Explain what a timeline is.

- Model (demonstrate) the making of a timeline yourself (you don’t have to use your own life – you could do a realistic one based anonymously on someone you know). Modelling is an excellent way of supporting pupils to learn a new skill/behaviour. Draw this timeline on the board and talk through what you are doing, or have one prepared on a large roll of paper. Remember to use a suitable scale – a year should be represented by a particular length. (When your pupils come to do their timelines, they could use 5 cm or the length of a hand if they don’t have rulers.)

- Ask pupils to write down key things they remember about their lives and also given them time to ask their parents/carers about when they first walked etc.

- Ask them to record any other information they want to include on their timeline.

- Support them as they make their timelines. You could encourage them to write in the main events that have happened to them personally, and in a different colour (or in brackets under the line) the main events that happened to their wider family (e.g. older sister went to college, father bought a field etc.).

- Display their timelines in the classroom.

- Pupils who finish quickly could be asked to imagine and draw a timeline of their future. What will be the main events when they are 20, 25, 40 etc.?

3. Helping pupils explore their past

Helping pupils to develop their understanding of past and present takes time, and involves giving them a range of activities where they have to observe, ask questions and make judgements about what they find out.

How can they develop skills to help them think about how things change over time? Case Study 3 and the Key Activity use the wider environment to extend your pupils’ understanding of time passing and things changing.

Case Study 3: Visiting an older citizen

Mr Obi, Mrs Okafor and Miss Ugwu planned their social studies together. They did not all do the same topic at the same time, but it helped them to share ideas.

They all read Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource. They planned to take their classes to visit an older member of the community to talk to them about how the village has changed since they were a child. They decided to organise the classes into groups and each group would prepare questions to ask the elder. Each group would have a different area to think about such as games they played, food they ate, houses they lived in etc.

Key Activity: Using different sources to investigate family life in the past

Do a brainstorm with your class. Ask them to consider how they could investigate the ways in which life for their families has changed in the village/community over time. What sources could they use to find out about this?

They are likely to come up with ideas such as: using their own observations and memories to think about what has changed in their own lifetime; asking their parents; talking to other older people; talking to people in authority (such as the chief); looking at older maps; using a museum (if there is one); reading from books about the area etc.

Ask the pupils to gather stories from their own families about how life has changed for them over the last few generations. What was everyday life like for their grandparents and great grandparents? What are the family stories from previous times? Does the family have any old newspapers, photos, letters, etc. that help show what life used to be like?

Pupils could share their stories with each other in class and use them as a basis for presentations – these could include pictures of what they think life was like, role plays about life in the past, written factual accounts based on family stories and other documents, and imaginary stories e.g. ‘describe a day in the life of your grandmother when she was young’.

Resource 1: Kinship chart

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

A kinship chart shows how each person is related or connected to the others and their family or community. Different cultures have different ways of describing relatives.

Below is a simple kinship chart for Nigeria.

Me _____________ | My Parents Father _______________ Mother ______________ | My Grandparents Grandfather __________ Grandmother _________ |

| My Brothers/ Sisters _____________ _____________ _____________ | Grandfather __________ Grandmother _________ |

Resource 2: Another kinship chart

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Resource 3: My timeline

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

| Date | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | |

| Event | Born | 1st steps | 1st words | First memory | Sister born | Started school | Went to clinic for stitches | Brother born | ||||

| Year | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

Section 2: Investigating how we used to live

Key Focus Question: How can you develop your pupils’ thinking skills in history, using oral and written sources?

Keywords: evidence; history; thinking skills; interviews; questions; investigations

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used oral history and documents to develop pupils’ thinking skills in history;

- planned and carried out activities that help pupils gather and use oral evidence to find out about past events.;

Introduction

When we study history as part of social studies, we place a great deal of importance on the sources of evidence that can tell us something about the past.

There are two important ways of gathering evidence about the past – finding and analysing documents that record what happened and using oral history. Oral history is the gathering of people’s stories about particular events. We can also look at objects, pictures and buildings from the past to find out more.

In this section, you will encourage your pupils to investigate documents and conduct oral interviews in order to help build their understanding of their own past. It is important to encourage pupils to ask questions and listen to each other’s ideas, so they develop skills in assessing evidence and drawing conclusions.

1.Gathering oral histories

Teaching history does not only involve facts about historical events, but also the development of pupils’ historical skills. As a teacher, you need give your pupils the opportunity to develop and practise these skills. The kinds of events you explore with your pupils will depend on their ages. With younger children, you will also take more of a lead in helping them find out and understand what happened.

In this part, pupils will conduct oral interviews with an older family member or another member of the community. The aim of the interview is to find out how different their own lifestyles and interests are, compared with those of people in the past. By showing pupils how to conduct an oral interview, you can help develop important skills – being able to see the value of oral history and being able to listen. (Read Resource 1: Oral history now to find out more about this valuable resource.)

Case Study 1 shows how one teacher introduced her pupils to the idea of using oral history to find out about the past. Read this before trying Activity 1 with your class.

Case Study 1: Family oral histories

Every person has a history. Mrs Eunice Shikongo, a Grade 5 teacher at Sheetheni School on the outskirts of Windhoek in Namibia, wants her pupils to explore their own family histories by interviewing one family member.

First, she discusses what oral evidence is, by encouraging pupils to share things they have learned from their grandparents. She asks them: ‘Has what you have learned been written down?’ Most agree that things learned in this way are not written, but passed on by word of mouth. Mrs Shikongo then explains that, by conducting an interview, pupils will collect oral evidence about what the past was like and will find out what a valuable source of evidence this can be.

She helps them compile a list of interesting questions to use to interview their family members (see Resource 2: Possible interview questions). The pupils then add their own questions to the list before carrying out these interviews at home.

The next day, they share their findings with the rest of their class. Mrs Shikongo summarises their findings on the board under the heading ‘Then’. Next, she asks them to answer the same questions about their own lives, and summarises this information under the heading ‘Now’. She asks them to think about how their lives are different from the lives of their family members in the past. She then asks the pupils, in pairs, to compare ‘Then’ and ‘Now’. Younger pupils write two/three sentences using words from the board. Older pupils write a short paragraph

Activity 1: Oral interviews about childhood

- First organise your pupils into pairs. Then tell them to think of some questions they can ask an older person about his/her childhood. Give the pupils time to think up their questions and tell them how long they have to do this task – maybe two or three days. If you have younger pupils, you could work together to make up three or four questions they could remember and ask at home.

- When they have asked the questions at home, ask the pupils to share their information with their partners.

- Then ask each pair of pupils to join with another pair and share what they have found out.

- Now ask each group of four to complete a table to show how life has changed.

- Discuss with the whole class how life has changed since their parents and/or grandparents or other older people were children. Pose questions that encourage them to reflect on why such changes have taken place. (Key Resource: Using questioning to promote thinking can help you think of the kinds of questions you need to ask to stimulate pupils. You could note some of these down before the lesson to remind you at this stage.)

- Make a list of the key changes on the board.

2. Investigating a historical event

As well as using oral histories to find out about life in the past, you can use written records with your pupils.

In this section, we look at how different sets of records can help pupils build up their understanding of the past. In Activity 2 and the Key Activity, pupils explore written records of past events and conduct oral interviews with community members. How you organise and gather resources together is part of your role and advice is given on how you might do this.

Case Study 2: Using written records to explore past events

Mr Adamu is a teacher of Primary 6 at the Government Primary School in Kanamana Yobe State in Nigeria. The anniversary of the Nigerian Civil War is coming up and he wants his pupils to think about the events that led up to the war.

He sends his class to the library where they read up on the events. Two local newspapers, The Star and The Guardian, have just published supplements about the war and he reads extracts from these to his pupils to stimulate their interest. These articles contain profiles of the lives of some of the people who were involved. He divides his class into groups and asks each group to take one of these people and to research and then write a profile of that person on a poster, for display in the school hall. The poster must include how they were involved and what has happened to them since.

Mr Adamu’s pupils then plan to present their findings to the whole school. Their posters are displayed around the hall and some of the pupils speak at the assembly.

Resource 3: The Nigerian Civil War gives some background information

Activity 2: Researching an important date in history

This activity is built on a visit to a museum, in this case the National Museum in Onikan, Lagos, but you could use a more local site. (If it is not possible for you to visit a museum, you could collect together some newspaper articles, pictures and books to help your pupils find out for themselves about an event.)

- Decide on a particular historical event that you wish your pupils to investigate during the visit to the museum (or in class if you have the resources), e.g. the role women played in the Aba riot in October 1929 (see Resource 4: The Aba women’s riot). It is important that you focus the attention of your pupils on a particular event, especially if they are visiting a museum covering many years of the past.

- Divide the class into groups, giving each a different issue or aspect of the historical event to focus upon.

- Discuss what kinds of questions they might need to find the answers to as they read and look at the exhibitions (if at museum) or materials (if in school).

Back in class, ask the pupils in their groups to write up their findings on large posters. Display these in the classroom or school hall for all to see.

3. Thinking critically about evidence

This part is intended to extend your ideas of how to help pupils use oral history as a resource for finding out about the past. You will encourage them to think critically about the validity and reliability of such evidence, and to compare oral testimonies of a historical event with written evidence of the same event. Investigating the similarities and differences in the two types of evidence provides an exciting learning opportunity for pupils.

Case Study 3: Collecting oral testimonies

Mrs Okolo teaches social studies to Primary 6 at a small school just outside Aba, Nigeria. Many of the families have older members who remember or were part of the Aba women’s riot of 1929. Resource 4 gives some background information. Mrs Okolo has invited two people to come to the school, to speak about their experiences. (See Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource as this will help you plan and organise such a visit.) They will come on consecutive days as they do not know each other and have differing views about the role played by the women.

Mrs Okolo warns her class that these two women are now very old, and that an older person’s memory is not always very good. Before the guests arrive, the pupils prepare some questions that they want to ask the women. Over two days, the visitors come and tell their stories. The pupils listen carefully and ask them questions.

In the next lesson, Mrs Okolo and the class discuss the similarities and differences between the two accounts. They think about why the two women have different views on the events.

Mrs Okolo lists the key points that came out of their stories and also stresses that, when they were young, being members of the Aba women’s riot was very important to these women, and they may have romanticised their involvement. She explains that while these oral histories may give pupils some understanding of the Aba women’s riot, they may not always be accurate, and the stories that different people tell may vary considerably.

Mrs Okolo believes her class learned a valuable lesson in the uses and problems of gathering oral evidence of history.

Key Activity: Comparing oral interviews and written texts

- With your pupils, identify an important historical event (such as a local feud or uprising) that took place in your area in the past. If you can, find a short written text about it. Resource 4 gives one example you could use if you cannot find another event.

- In preparing this activity, you need to gain an understanding for yourself (as a teacher) about what people in your community know about the uprising or event in question. These ‘memories’ are the oral stories that have been passed down from person to person. Identify some key people who your pupils could talk to at home or could come into school.

- Send your pupils out in groups to interview these older people. Ask the pupils to record ten key points made by each interviewee. (Make sure that pupils only go in groups and that they are safe at all times.)

- Back in class, ask your pupils to feed back their key findings.

- Ask each group to design a poster of the event, including the key events and using some of the visitor’s comments to give a feeling of what it was like to be there.

- Display these in class.

- Discuss with your pupils whether they think they have enough clear evidence about what happened from the people they spoke to. If not, how could they find out more?

Resource 1: Oral history

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Introduction

We all have stories to tell, stories about our lives and special events that have taken place. We give our experiences an order and organise such memories into stories. These stories could, if collected together with other people’s memories of the same event, allow us to build up a clearer picture of what actually happened.

Your local community will be a rich source for exploring what happened at a particular event or what it was like to live there 20 years ago. Your pupils could investigate the Nigerian Civil or Biafran War or some other more local event.

What is oral history?

Oral history is not folklore, gossip, hearsay or rumour, but the real history of people told from their perspectives, as they remember it. It involves the systematic collection of living people’s stories of their own experiences. These everyday memories have historical importance. They help us understand what life is like. If we do not collect and preserve those memories, then one day they will disappear forever.

Your stories and the stories of the people around you are unique and can provide valuable information. Because we only live for so many years we can only go back one lifetime. This makes many historians anxious that they may lose valuable data and perspectives on events. Gathering these stories helps your pupils develop a sense of their own identities and how they fit into the story of their home area.

How do you collect people’s stories?

When you have decided what event or activity you want to find out about, you need to find people who were involved and ask if they are willing to tell you their stories.

Contact them to arrange a time of day and tell them what you want to talk about and what you will do.

You need to record what your interviewee says. You can do this by taking notes by hand or possibly by tape recording or video recording.

Having collected your information or evidence, it is important to compare and contrast different people’s views of the same event, so that you can identify the facts from the interpretations that different people put on the same event.You could ask your pupils, in groups, to interview different people and then to write a summary of their findings to share with the rest of the class. These could be made into a book about your class’s investigation into a particular event.

Adapted from: Do History, Website

Resource 2: Possible interview questions

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Below are some questions to use with a visitor to find out about an event in the past or how they used to do things in the past. Areas you could explore include:

- growing food;

- traditional dress;

- traditional healing;

- building houses;

- education.

These three sets of starter questions will help you support your pupils in thinking of their own questions.

(1) Historial events

- What historical events took place when you were young?

- What did you wear when you went to a party or a wedding?

- Which event do you remember most?

- What do you remember about it?

- What happened? Tell me the story as you remember it.

- Who else was with you?

- Could I speak to them about this still?

(2) Games

- What games did you play when you were a child?

- How did you play these games?

- Who taught you to play these games?

- When did you play them?

- Where did you play them?

- What other activities did you enjoy?

(3) Growing food

- What vegetables and fruit did you grow?

- How did you grow them?

- Where did you grow them?

- What tools did you use?

- What did vegetables cost at the time?

- Where did you buy them? Which ones did you buy?

- What else did you eat that you liked?

- Do you still eat these foods?

Resource 3: The Nigerian Civil War

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

The Nigerian Civil War, 1967–1970, was an ethnic and political conflict caused by the southeastern provinces of Nigeria proclaiming themselves as the republic of Biafra. The war was very violent and many places were besieged and cut off from the world. Many people, mainly Igbo, were killed or starved to death because provisions were blocked.

Causes of the conflict

The conflict was the result of serious tensions, both ethnic and religious, between the different peoples of Nigeria. Nigeria was a country put together by agreement between European powers who paid little notice to the historical African boundaries or population groups. Nigeria, which received independence from Britain in 1960, had a population of 60 million people with nearly 300 differing ethnic and tribal groups.

The largest groups were the largely Muslim Hausa in the north, the Yoruba in the half-Christian, half-Muslim, southwest, and the Igbo in the predominantly Christian southeast. At independence, a conservative political alliance had been made between the leading Hausa and Igbo political parties, which ruled Nigeria from 1960 to 1966. This alliance excluded the western Yoruba people. The well-educated Igbo people were considered by many to be the main beneficiaries of this alliance.

The elections of 1965 saw the Nigerian National Alliance of the Muslim north and the conservative elements in the west against the United Progressive Grand Alliance of the Christian east.

The alliance of north and west won a crushing victory under Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, amid claims of widespread electoral fraud.

Military coup

The claims of fraud led to a military coup on 15 January 1966, which led to the accession of General Aguyi Ironsi, the head of the Nigerian army, as head of state of Nigeria. This coup benefited the Igbos because most of the coup plotters were Igbos and Ironsi. On 29 July 1966, the northerners carried out a counter-coup. It placed Lt. Col. Yakubu Gowon into power. Ethnic tensions due to the coup led to the large-scale massacres of Christian Igbos living in the Muslim north.

The discovery of large quantities of oil in the southeast of the country had led to the prospect of the southeast becoming self-sufficient and increasingly prosperous. However, the exclusion of easterners from power made many fear that the oil revenues would be used to benefit areas in the north and west rather than their own.

Break away

The military governor of the Igbo-dominated southeast, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu announced the breaking of the southeastern region from Nigeria as the Republic of Biafra, an independent nation on 30 May 1967 (29 May in some sources). Only four countries recognised the new republic.

The Nigerian government immediately launched a ‘police action’, using the armed forces to retake the declared independent territory.

Civil war

At first, Nigerian progress was slow, and failures of its larger army to invade the territory of the new republic led to a growth in worldwide support for Biafra. Biafran troops led by Colonel Banjo, a brilliant tactician, crossed the Niger River, entered the mid-western region, and launched attacks close to Lagos, the then Nigerian capital. However, reorganisation of the Nigerian forces, the reluctance of the Biafran army to fight and the effects of a naval, land and air blockade of Biafra led to a change in the balance of forces. Biafran forces were pushed back into their core territory, and the capital of Biafra, the city of Enugu, was captured by Nigerian forces. The Biafrans continued to resist in their core Igbo heartlands, which were soon surrounded by Nigerian forces.

Stalemate

From 1968 onwards, the war fell into a lengthy stalemate, with Nigerian forces unable to make significant advances into the remaining areas of Biafran control. The blockade of the surrounded Biafrans led to a humanitarian disaster when it emerged that there was widespread civilian hunger and starvation in the besieged Igbo areas. Farmland was sabotaged and this was affecting the Biafran population. Images of starving Biafran children went around the world. The Biafran government claimed that Nigeria was using hunger and genocide to win the war, and sought aid from the outside world.

Aftermath

Biafran forces surrendered in 1970 when Ojukwu fled to the republic of Cote d'Ivoire, leaving his deputy Philip Effiong to handle the details of the surrender. To the surprise of many in the outside world, the threatened reprisals and massacres did not occur, and genuine attempts were made at reconciliation.

It is estimated that up to a million people may have died in the conflict. Reconstruction, helped by the oil money, was swift. However, the old ethnic and religious tensions often remained.

On Monday 29 May 2000, The Guardian of Lagos reported that President Olusegun Obasanjo commuted to retirement the dismissal of all military persons who fought for the breakaway state of Biafra during the Nigerian Civil War. In a national broadcast, he said that the decision was based on the principle that ‘justice must at all times be tempered with mercy’.

Adapted from: Wikipedia, Website

Resource 4: The Aba women’s riot

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

In 1928–1930, Aba women protested against the oppressive rule of the colonial government. These Igbo women of eastern Nigeria feared that the headcount being carried out by the British would mean they were to be taxed. The women were unhappy about the over-taxation of their husbands and sons, which they felt was making them poor and causing hardship. The women also objected to the use of warrant chiefs to collect monies. Previously, new village leaders or heads had been chosen and removed by the people themselves. Decisions were reached informally or through village assemblies. While they had less influence than men, women did control local trade and specific crops. Women protected their interests through assemblies. This was changed by the colonial government, which appointed its agents as warrant chiefs to rule over the people. These British-appointed African judges and tax enumerators abused their position, obtaining wives without paying the full bride prize and seizing property.

The women staged a protest on 24 November 1929. They held an all-night song and dance ridicule (‘sitting on a man’). The women’s protest spread. Ten thousand women rioted and the demonstrations swept through the Owerri-Calabar districts.

A warrant chief, Chief Okugo, had had to count the population and livestock for taxation purposes. The women sang ‘Ma O ghara ibu nwa beke mma anyiu egbuole Okugo rie’ (‘If it were not for the white man we would have killed Chief Okugo and eaten him up’).

The women attacked three specific targets:

- the native courts;

- any European-owned factories; and

- warrant chiefs from native courts where sessions were in progress.

One warrant chief was pushed off his bicycle, his gun was taken away and the women chased him into the bush.

Late in December 1929, the women forced the Umuahia warrant chiefs to surrender their caps, thus launching their successful campaign to destroy the warrant chief system. In Aba, women sang and danced against the chiefs and then, according to an observer, ‘proceeded to attack and loot the European trading stores and Barclays Bank and to break into the prison and release the prisoners’. Some 25,000 Igbo women faced colonial repression and, over a two-month period of insurrection, December 1929 to January 1930, at least 50 were killed. But this effectively ended the warrant chief system.

Adapted from: On War, Website

Section 3: Using different forms of evidence in history

Key Focus Question: How can you use mind mapping and fieldwork to develop historical skills?

Keywords: historical skills; mind mapping; fieldwork; investigations; history; maps

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used pictorial maps to help pupils see the importance of the natural environment in human settlement patterns (see also Module 1, Section 2);

- used small-group investigations, including fieldwork, to develop pupils’ understanding of early African societies.;

Introduction

In addition to looking at oral and written evidence, your pupils can also learn about the past from other sources, for example maps.

In this section, you will structure lessons and activities that will help pupils understand the factors that led to the emergence of strong African kingdoms in the past. It provides you with insight into the kinds of evidence and resources you can use.

It covers:

using maps and other documents to examine factors in the natural environment that influenced the nature of the settlement and the kingdom;

exploring the role of pastoral and agricultural practices in shaping African lifestyles and culture;

exposing pupils to the material evidence that remains in and around settlements, which will help them examine how the past is reconstructed.

1. Thinking about the location of settlements

By looking at the local environment and the physical layout of the land, it is possible to think about why a community settled in a certain place.

Great Zimbabwe provides a good example. It is important that as a social studies teacher you understand a case like this, as it gives you the skills to relate these ideas to a number of different ancient African kingdoms and to your local setting. Using fieldwork, such as actual trips to a site, allows pupils to see for themselves why one place was chosen for settlement and why some developments survived longer than others.

Most settlements are where they are because the environment provides some kind of resource, such as water or trees, and/or the site provides protection from the elements and, in earlier times, from enemies. Villages and towns are often found near a stream or wood to provide water and wood for shelter and to burn for heat and cooking. By looking closely at your school’s local environment or your pupils’ home environment, whichever is easier, you can help them to begin to understand how settlements developed.

Maps from earlier times will show how a site has changed over time (this can build on the time walk activity from Module 2, Section 1).

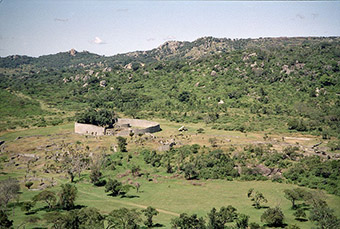

Case Study 1: Investigating heritage sites

Ms Sekai Chiwamdamira teaches a Grade 6 class at a primary school in Musvingo in Zimbabwe. Her school is near the heritage site of Great Zimbabwe. She knows that many of her pupils pass by this magnificent site of stone-walled enclosures on their way to school. But she wonders whether they know why it is there. Sekai wants to help her pupils realise that the landscape and its natural resources played an important part in people’s decision to settle in Great Zimbabwe.

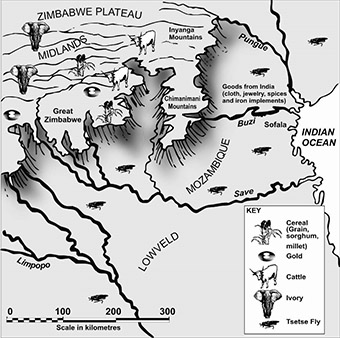

She begins her lesson by explaining how Great Zimbabwe was a powerful African kingdom that existed between 1300 and 1450 (see Resource 1: Great Zimbabwe). She asks the pupils to consider why the rulers of this kingdom chose to settle in the Zimbabwe Plateau rather than anywhere else in Africa. A map is her key resource for this discussion (see Resource 2: Pictorial map of Great Zimbabwe). One by one, she points out the presence of gold, ivory, tsetse fly, water supply and access to trade routes on the map; she asks her pupils to suggest how each of these led people to establish the settlement where they did. As her pupils suggest answers, Sekai draws a mind map on the board (see Key Resource: Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideas).

Sekai is pleased at the level of discussion and thinking that has taken place.

Activity 1: Using a map to gain information about Great Zimbabwe

Before the lesson, copy the map and questions from Resource 2 onto the chalkboard or have copies ready for each group.

- First, explain what a key represents on a map. Then divide the class into groups and ask each group to analyse the key relating to the map of Great Zimbabwe. Agree what each item on the key represents.

- Ask your pupils why they think the people first settled here. You could use the questions in Resource 2 to help them start their discussion.

- As they work, go around the groups and support where necessary by asking helpful questions.

- After 15 minutes, ask each group to list their ideas.

- Next, ask them to rank their ideas in order of importance.

- Write down their ideas on the chalkboard.

- Finally, ask pupils to vote on which they think are the three most important factors.

With younger children, you could look at local features and ask them to think why people settled here.

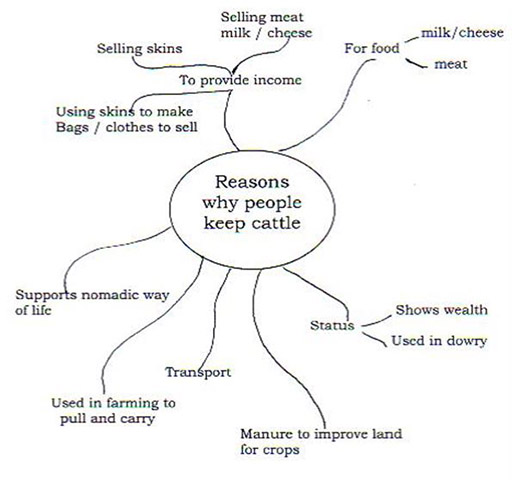

2. Using mind maps to structure thinking about the past

In the past, cattle were always viewed as an important resource, and many farmers and communities still view cattle this way.

The purpose of Activity 2 is for pupils to investigate the traditional role of cattle in African societies using the local community as a source of information. They will then determine how much African farming societies have changed.

Case Study 2 and Activity 2 use mind mapping and a template to help pupils think about the task as they work together in groups to share ideas.

Case Study 2: Farming in Birnin Kebbi

There are many farmers living in the Birnin Kebbi area and many of the pupils in the school are children of farmers. Bilkisu wants to investigate with her class how important cattle were to the lifestyle and culture of the early African farmers who settled in Nigeria. She also wants her pupils to think about the extent to which African farming societies have changed. She plans to use the local community as a resource of information.

Bilkisu begins her lesson by explaining the important role of cattle in early African societies. She draws a mind map on the chalkboard that highlights the importance of cattle, and what cattle were used for. (See Key Resource: Using mind maps and brainstorming to explore ideasand Resource 3: A mind map about keeping cattleto help you question your pupils.) The class discuss these ideas.

In the next lesson, in small groups with a responsible adult, the pupils go out to interview local farmers. Bilkisu has talked with them beforehand to see who is willing to talk with her pupils.

- The pupils had two simple questions to ask local farmers:

- Why are cattle important to you?

- What are the main uses of cattle?

Back in class, they share their findings and Bilkisu lists their answers on the chalkboard. They discuss what has changed over the years.

Activity 2: Farming old and new

- Before the lesson, read Resource 4: Cattle in traditional life – the Fulani

- Explain to pupils why cattle were important to the people who live in northern Nigeria.

- Ask them, in groups, to list reasons why people used to keep cattle.

- For homework, ask them to find out from older members of the community how keeping cattle has changed.

- In the next lesson, ask the groups to copy and then fill out the template in Resource 5: The role of cattle – past and present to record their ideas.

- Share each group’s answers with the whole class and display the templates on the wall for several days so pupils can revisit the ideas.

3. Fieldwork to investigate local history

One way to reconstruct how societies in the past lived is to analyse buildings, artefacts, sculptures and symbols found on sites from a long time ago.

In this part, pupils go on a field trip to a place of historical interest. If this is not realistic for your class, it is possible to do a similar kind of task in the classroom by using a range of documents, photographs and artefacts. Pupils can start to understand how to investigate these and fill in some of the gaps for themselves about what used to happen.

Case Study 3: Organising a field trip

Aisha has already explored with her Primary 5 pupils that Sokoto Caliphate was a powerful political empire with a strong ruler. Now she wants them to think about how we know this. As her school is near Sokoto, she organises a field trip. She wants the pupils to explore the buildings and artefacts, and think about how historians used this evidence to construct the empire’s history.

At the site, the pupils take notes about what the buildings look like. They also describe and draw some of the artefacts and symbols that can be found in and around each of these buildings.

Back at school, they discuss all the things they saw and list these on the chalkboard. Aisha asks them to organise their findings under headings for the different types of building they have seen. The pupils then discuss what they think the different buildings were used for, based on what they looked like and the artefacts and sculptures that were found there. Aisha helps fill in the gaps by explaining aspects of Fulani culture and the meaning of some of the sculptures and artefacts. The ideas are displayed and other classes are invited to see the work.

See Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource.

Key Activity: Exploring local history

- Before you start this activity, gather together as much information as you can about the local community as it used to be. You may have newspaper articles, notes of talks with older members of the community, names of people who would be happy to talk to your pupils.

- Organise your class into groups. Explain that they are going to find out about the history of the village using a range of resources. Each group could focus on one small aspect, for example the local shop, or church, or school.

- Look at the resources you have, if any, before going to talk to people.

- Give the groups time to prepare their questions and then arrange a day for them to go out to ask about their area.

- On return to school, each group decides how to present their findings to the class.

- Share the findings.

- You could make their work into a book about the history of your local area.

Resource 1: Great Zimbabwe

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Great Zimbabwe, or ‘houses of stone’, is the name given to hundreds of great stone ruins spread out over a 500 sq km (200 sq mi) area within the modern-day country of Zimbabwe, which itself is named after the ruins.

The ruins can be broken down into three distinct architectural groups. They are known as the Hill Complex, the Valley Complex and the famous Great Enclosure. Over 300 structures have been located so far in the Great Enclosure. The types of stone structures found on the site give an indication of the status of the citizenry. Structures that were more elaborate were built for the kings and situated further away from the centre of the city. It is thought that this was done in order to escape sleeping sickness.

What little evidence exists suggests that Great Zimbabwe also became a centre for trading, with artefacts suggesting that the city formed part of a trade network extending as far as China. Chinese pottery shards, coins from Arabia, glass beads and other non-local items have been excavated at Zimbabwe.

Nobody knows for sure why the site was eventually abandoned. Perhaps it was due to drought, perhaps due to disease or it simply could be that the decline in the gold trade forced the people who inhabited Great Zimbabwe to look elsewhere.

The ruins of Great Zimbabwe have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986.

Adapted from: Wikipedia, Website

Resource 2: Pictorial map of Great Zimbabwe

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

- Find Great Zimbabwe.

- Find the Zimbabwe Plateau. Why do you think the founders of Great Zimbabwe decided to build the settlement on a plateau?

- What natural resources were found in and around the region of Great Zimbabwe?

- Why were these resources important?

- What other environmental factors may have contributed to the people’s decision to settle on the Zimbabwe Plateau?

Original source: Dyer, C., Nisbet, J., Friedman, M., Johannesson, B., Jacobs, M., Roberts, B. & Seleti, Y. (2005). Looking into the Past: Source-based History for Grade 10. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman. ISBN 0 636 06045 4.

Resource 3: A mind map about keeping cattle

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Resource 4: Cattle in traditional life – the Fulani

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

The Fula or Fulani are an ethnic group of people spread over many countries in West Africa, including Nigeria. The ancient origins of the Fula people have been the subject of speculation over the years, but several centuries ago they appear to have begun moving from the area of present-day Senegal eastward.

The Fulani are traditionally a nomadic, pastoralist people, herding cattle, goats and sheep across the vast dry hinterlands (remote areas) of their domain, keeping somewhat separate from the local agricultural populations.

A Fulani family needs at least 100 heads of cattle in order to live completely off their livestock. When the number of livestock drops, the family must start farming to survive.

The Sokoto Fulani of Nigeria

The Sokoto Fulani are a sub-group of this much larger Fulani group and live in northern Nigeria alongside the Hausa people. The Sokoto region houses some of the ruling class of the Fulani, known as the Toroobe.

The area they occupy is open grassland with narrow forested zones. Camels, hyenas, lions, and giraffes inhabit this region. Though the temperatures are extremely hot during the day, they are much cooler at night.

What are their lives like?

The semi-nomadic Sokoto Fulani engage in some supplementary farming, along with animal breeding. Millet and other grains are their main crops. Milk, drunk fresh and as buttermilk, is their staple food, and meat is consumed only during ceremonial occasions. The cattle are herded by the men, although the women help with milking the cows. The women also make butter and cheese and do the trading at the markets. Among the Fulani, wealth is measured by the size of a family's herds.

The semi-nomadic Sokoto Fulani live in temporary settlements. During the harvest, the families live together in small huts that make up village compounds. During the dry season, the men leave their wives, children, the sick and the elderly at home while they take their herds to better grazing grounds. Each village has a chief or headman to handle village affairs.

Adapted from: Wikipedia, Website

Resource 5: The role of cattle – past and present

![]() Pupil use

Pupil use

| The role of cattle in the past | The role of cattle today |

| Cattle were important for: | Cattle are important for: |

| |

| |

|

Section 4: Understanding timelines

Key Focus Question: How can you help pupils explore who they are in ways that are sensitive and stimulating?

Keywords: timelines; historical change; chronology; history; historical sources; debate

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used timelines to represent historical change over time;;

- helped pupils to identify the key events in a particular historical process;

- encouraged pupils to view history not just as a series of dates to be learned but as a process to be investigated;.

- used a variety of sources to help pupils see that one event may have many causes.

Introduction

When developing an understanding of time past and passing, it is important to be able to sequence events into the order in which they happened.

Pupils often struggle with the concept of time. In this section, you will first help your pupils to divide time into periods that are more manageable and then, once they are able to do this, think about the order of events and why this is important. (With young pupils, this might be as simple as helping them order how they do certain tasks, leading on to more complex activities as their understanding grows.) You will then help your pupils identify the most important events in a particular passage of time. This can lead, with older pupils, into an analysis of cause and effect, and the understanding that there is usually more than one cause of an event.

1. Building a timeline

Investigating a particular period in history, and trying to sequence events in the order in which they happened, will help pupils begin to see the links between events and some of the possible causes. Understanding the causes of change in our countries and societies may help us to live our lives better.

The purpose of this part is to explore how using timelines in history can be a useful way to divide time into more manageable ‘bits’, so that we know which ‘bit’ or period we are dealing with. This is particularly important when we are teaching history, because it is crucial that pupils understand the idea of change over time.

From an early age, pupils need help to sort and order events. As they grow and experience life, they can revisit activities like these ones, using more complex sequences and events.

(Section 1 in this module used timelines to explore family history. You might find it helpful to look at that section if you have not done so already, particularly if you are working with younger pupils.)

Case Study 1: Ordering events

Ms Tetha Rugenza, who teaches history at a small school in Rwanda, wants to show her Grade 4 class how to divide up time into smaller periods. In order to do this, she plans a lesson where she and her pupils explore how to construct a timeline and divide it into periods.

Ms Rugenza decides to use the example of Rwanda. She draws a timeline on the board of the history of Rwanda. To help pupils understand the concept of periods, she divides the history of Rwanda into the pre-colonial, the colonial and the independence period. To give a sense of how long each of these periods is, she draws each period to scale.

She writes a list of important events, together with the date on which they took place, on separate pieces of paper and displays these on a table. Each event, she tells the class, falls into a particular period. She asks her pupils to work out which events fall into which period and in which order, doing a couple of examples herself. She calls out one event at a time and allows a pupil to come and stick it next to the appropriate place on the timeline. The rest of the class check that it has been put in the correct place. Through discussion, she helps the pupils if they are not sure where an event should go. She asks them if they can think of any other national events that should be placed on the timeline and adds them as appropriate.

Activity 1: Drawing timelines

Tell the class that they are going to make a timeline of the school year together.

- Start the lesson by asking your pupils to write down the most important events that have taken place in school during the year.

- Ask them to give each event a date if they can, or to find this out.

- Ask pupils to order these events from the beginning to the end of the school year.

- Help pupils to decide on how big they want their timelines to be and to create a scale accordingly.

- Ask pupils to mark out each month correctly in terms of their chosen scale and to write down the event dates on the left-hand side of the timeline – starting at the bottom of their timeline with the past, and working up to the present at the top.

- On the right-hand side of the timeline, ask pupils to write a short description of the appropriate event next to each date.

- Display the timelines for all to see.

- (If you do not have enough resources for this to be done individually then it can be done in groups of up to five pupils.)

- Discuss as a whole class whether there are some school events that could happen at any time of the year. Are there some that have to happen at a particular time? Why? (End-of-year exams, for example – why can’t they happen at the start of the year?)

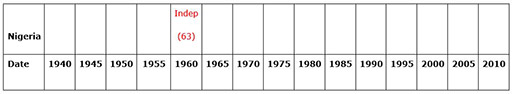

2. Introducing the concept of chronology

The study of time and the order in which events took place over time is called chronology. This part explores how you can help pupils understand this sequencing of events, the relationship between the order events happen and the outcomes. In using these activities with pupils, you will realise the importance this has on their understanding of the past.

Case Study 2: Ordering events

Mr Ademola wants to show his Primary 5 pupils how chronology affects their understanding of events. He writes the following sentences on the chalkboard:

- A body of a man lies on the floor in the room.

- A man is arrested for murder.

- Two men go into the room.

- A man leaves the room.

- A man screams.

He asks the pupils to rearrange these sentences into an order that makes sense and to provide a reason for why they think the sentences should go in that particular order. Mr Ademola uses this exercise to show how important it is to place events in a logical order.

However, he also wants pupils to begin to see the connections between events, and how one event influences another. He tells the class about the events in Nigeria since independence from British rule to the present democratic rule. (See Resource 1: Some important historical events since independence.) Using some of these events, he and his pupils construct a timeline on the chalkboard. He has selected a short section of Resource 1 so that his pupils are not confused by too much information. He cuts these events up into strips and asks his pupils to put them in date order. He asks his pupils if they can identify the most important events that changed the course of Nigerian history.

Mr Ademola is pleased that his pupils are beginning to see chronology as the first step in explaining why things happen.

Activity 2: Identifying key events

- Give pupils, individually or in groups, a copy of a story from a local newspaper; or you could read the story to them and ask them to make notes as they listen; or you could copy the story onto the chalkboard for pupils to read. Choose the story for its interest and the sequence of events it contains.

- Ask pupils to:

- read through the story;

- underline what they think are the important events that took place;

- using the events that they have underlined, create a timeline. Remind them about the importance of listing the events in order;

- mark on their timeline the event they believe is the key event;

- explain below the timeline why they have chosen that particular event as most important. In other words, how did that event cause later events?

- share their answers and, by discussion, agree the key event and then discuss whether or not this key event was the only cause of later events.

3. Comparing African histories

Timelines can help us compare the similarities and differences in a series of events for different people, or different groups, or different countries.

For example, if your pupils drew timelines for themselves, there would be some events the same (starting school) and others different (birth of baby brother or sister for example).

Using timelines to compare the history of a variety of African countries during the time of moving to independence can help your pupils see common themes but also differences between their experiences.

Case Study 3: Examining the passage of different African countries to independence

Mrs Adjei organised her class to work in groups to make a comparative multiple timeline that helped them to learn about the experiences of their own and other countries’ journey towards independence.

For each country that she chose she made a long strip of paper (she did this by sticking A4 pieces of paper together, one piece equalling five years). See Resource 2: African timelines template.

This would enable the groups, when finished, to place one under another to allow for easy comparison.

With her own books, and books and other materials borrowed from a colleague in a secondary school, the groups carried out their own guided research to find out the major events for each chosen country and then wrote each event in at the correct time on the chart. (For younger classes you could provide the events and dates yourself to help them construct the timeline.) Resource 3: Key events in the move to independence provides examples of some key dates and also suggests websites where further information can be found if necessary.

Mrs Adjei made the timeline for ‘World events’ as an example (World War II, independence for India, first flight in space, the Cold War, Vietnam War, the invention of the Internet, Invasion of Iraq etc.).

She made sure that each ‘country’ wrote ‘Independence’ in the appropriate time spot in another colour.

When all the groups had finished, she asked them to line up their timelines one under the other neatly. This enabled easy comparison between the countries.

Key Activity: Comparing the African experience

- Follow the activity carried out in Case Study 3.

- When the timelines have been completed, let each group introduce their country and talk through their timeline.

- Prepare a series of questions for the class to answer, for example:

- What are the major events on the timelines?

- What similarities can you see between the experiences of different African countries?

- What are the major differences?

- Which countries were the first to gain independence and which were the last?

- Which countries have suffered most from internal wars since independence?

- What major events are soon to happen (e.g. South Africa hosting the World Cup in 2012)?

- (This sort of work can easily be extended. Groups can carry on researching their designated countries to find out more about them: languages spoken; major industries; agriculture; cities and towns etc. They could draw maps of their countries and label them. There are many possibilities.)

Resource 1: Some important historical events since independence

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

| Date | Event |

| 1 Oct 1960 | Independence day. |

| 1 Oct 1963 | Nigeria becomes a republic. Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe is president of Nigeria. |

| 14–15 Jan 1966 | First military coup in Nigeria. Major-General J T U Aguiyi-Ironsi becomes head of state. Several politicians killed. |

| 29 July 1966 | Second military coup. General Ironsi killed. Lt Col Yakubu Gowon becomes head of state. |

| 27 May 1967 | Lt Col Gowon creates 12 states out of the four regions of Nigeria (Western, Northern, Eastern and Mid-West Regions). |

| 30 May 1967 | Lt Col Ojukwu, the military governor of Eastern Nigeria, declares the East as the ‘Independent State of Biafra’. |

| 6 July 1967 | A civil war breaks out between those that want the country united and those that don’t. |

| 12 Jan 1970 | ‘Biafra’ surrenders to the federal government and the people of the Eastern Region rejoin united Nigeria again. |

| 29 July 1975 | Corruption and disagreement brings the third military coup. General Murtala Mohammed becomes head of state. |

| 3 Feb 1976 | General Murtala Mohammed creates 19 states out of Nigeria’s 12-state structure. Abuja named as the new federal capital. |

| 13 Feb 1976 | Another military coup. General Murtala killed. |

| 14 Feb 1976 | General Olusegun Obasanjo steps in as head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. |

| July–Sept 1979 | Preparation to return to civil rule. General elections. |

| 1 Oct 1979 | Alhaji Usman Aliyu Shehu Shagari is first president of Nigeria’s SecondRepublic. |

| Aug 1983 | Second general elections. President Shehu Shagari returns to power. |

| 31 Dec 1983 | President Shehu Shagari arrested at Abuja and his government toppled in a military coup. |

| 1 Jan 1984 | Major-General Muhammadu Buhari becomes head of state. |

| 27 Aug 1985 | Military coup topples General Muhammadu Buhari’s government. Major-General Ibrahim Babangida becomes head of state. |

| Oct 1987 | Two new states created by General Babangida to bring Nigeria to a 21-state structure. |

| Oct 1991 | Nine new states created by General Babangida to bring Nigeria to a 30-state structure. |

| Dec 1991 | Elections into the state houses of assembly held. |

| 12 June 1993 | Presidential election held. The results, believed to favour Basorun M K O Abiola, are withheld, and political crisis begins. |

| 26 Aug 1993 | Interim national government formed with Chief Ernest Shonekan as head of state. |

| 17 Nov 1993 | General Sanni Abacha sacks the interim national government and becomes head of state. |

| Oct 1996 | Six states created by General Sanni Abacha from the 30-state structure, bringing Nigeria to a 36-state structure. |

| 15 March 1997 | Local government elections on party basis held throughout the country. This is after the government has formed five political parties. |

| 6 Dec 1997 | Elections into the state houses of assembly held. |

| 25 April 1998 | Elections into the national assembly held. |

| 8 June 1998 | General Sanni Abacha suddenly dies. |

| 9 June 1998 | General Abdusalami Abubakar takes over as new head of state. |

| From 15 June 1998 | Many political detainees released. |

| 20 July 1998 | General Abubakar dissolves the five political parties, cancels all the elections and sets 29 May 1999 as the new handover date to civilian government. |

| 14 Dec 1998 | Three political parties are registered by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) to participate in elections at local government, state and national levels. Alliance for Democracy (AD), All People’s Party (APP), and People’s Democratic Party (PDP). |

| 28 March 1999 | Chief Olusegun Obasanjo declared winner of the presidential elections on the platform of the PDP. |

| 29 May 1999 | Chief Olusegun Obasanjo takes over as elected civilian president. He starts a campaign against corruption and injustice. |

| 1 Oct 1999 | President Olusegun Obasanjo launches the Universal Basic Education (UBE), a free and compulsory primary education through junior secondary level. |

| 12 April–3 May 2003 | National and state assembly elections (contested by 30 registered political parties) held. |

| 19 April 2003 | Governorship and presidential elections held. President Olusegun Obasanjo re-elected. |

| 29 May 2003 | President Olusegun Obasanjo sworn in for another four-year term. |

Resource 2: African timelines template

![]() Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Teacher resource for planning or adapting to use with pupils

Resource 3: Key events in the move to independence

![]() Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

Background information / subject knowledge for teacher

| 1957 | Ghana becomes first independent black state in Africa under Kwame Nkrumah through Gandhi-inspired rallies, boycotts and strikes, forcing the British to transfer power over the former colony of the Gold Coast. |

| 1958 | Chinua Achebe (Nigeria): Things Fall Apart, written in ‘African English’, examines Western civilisation's threat to traditional values and reaches a large, diverse international audience. |

| 1958 | All-African People's Conference: Resolution on Imperialism and Colonialism, Accra, 5–13 December 1958 |

| 1954–1962 | French colonies (Francophone Africa) oppose continued French rule despite concessions, though many eager to maintain economic and cultural ties to France – except in Algeria, with a white settler population of 1 million. Bitterly vicious civil war in Algeria ensues until independence is gained in 1962, six years after Morocco and Tunisia had received independence. |

| 1958 | White (Dutch-descent) Afrikaners officially gain independence from Great Britain in South Africa. |

| 1964 | Nelson Mandela, on trial for sabotage with other ANC leaders before the Pretoria Supreme Court, delivers his eloquent and courageous ‘Speech from the Dock’ before he is imprisoned for the next 25 years in the notorious South African prison Robben Island. |

| 1960–1961 | Zaire (formerly Belgian Congo, the richest European colony in Africa) becomes independent from Belgium in 1960. Then, in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi), ‘charismatic nationalist Patrice Lumumba was ... martyred in 1961, with the connivance of the [US] Central Intelligence Agency and a 30-year-old Congolese colonel who would soon become president of the country, Joseph Deséré Mobutu.’ (Bill Berkeley, ‘Zaire: An African Horror Story’, The Atlantic Monthly, August 1993; rpt. Atlantic Online) |

| 1962 | Algeria (of Arab and Berber peoples) wins independence from France; over 900,000 white settlers leave the newly independent nation. |

| 1963 | Multi-ethnic Kenya (East Africa) declares independence from the British. |

| 1963 | Charter of the Organisation of African Unity, 25 May 1963. |

| mid-60s | Most former European colonies in Africa gain independence and European colonial era effectively ends. However, Western economic and cultural dominance, and African leaders’ and parties’ corruption intensify the multiple problems facing the new nations. |

| 1965 | Rhodesia: Unilateral Declaration of Independence Documents. |

| 1966 | Bechuanaland gains independence and becomes Botswana. |

| 1970s | Portugal loses African colonies, including Angola and Mozambique. |

| 1976 | Cheikh Anta Diop (Senegal, 1923–1986), one of the great African intellectuals of the 20th century, publishes the influential and controversial book, The African Origin of Civilization, his project to ‘identify the distortions [about African history] we have learned and correct them for future generations’. |

| 1980 | Zimbabwe (formerly Southern Rhodesia) gains independence from large white settler population after years of hostilities. |

| 1970s–1980s | Police state of South African white minority rulers hardens to maintain blatantly racist and inequitable system of apartheid, resulting in violence, hostilities, strikes, massacres headlined worldwide. |

| 1986 | Nigerian poet/dramatist/writer Wole Soyinka awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature. |

| 1988 | Egyptian novelist and short story writer Nabuib Mahfouz awarded the 1988 Nobel Prize in Literature, the first prizewinning writer with Arabic as his native tongue. |

| 1994 | The Hutus massacre up to a million Tutsis in Rwanda; then fearing reprisals from the new Tutsi government, more than a million Hutu refugees fled Rwanda in a panicked mass migration that captured the world's attention. |

| 1996 | 500,000 of Hutu refugees streamed back into Rwanda to escape fighting in Zaire. |

| 2001 | After 38 years in existence, the Organisation for African Unity (OAU: http://www.oau-oua.org/) is replaced by the African Union. |

Adapted from: www.http://africanhistory.about.com/

Timeline – African countries in order of independence

Adapted from: http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/ Decolonization_of_Africa#Timeline

Section 5: Using artefacts to explore the past

Key Focus Question: Using artefacts to explore the past

Keywords: artefacts; evidence; group working; local history; environment; questioning

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will have:

- used artefacts to help pupils raise questions about and understand the past;

- developed lessons that allow pupils to think about their national history in relation to their own identities;

- involved local experts and the environment in your lessons to stimulate pupils’ interest in local history.

Introduction

Understanding who you are and having good self-esteem is enhanced if you have a strong sense of your identity and can see your place in the bigger pattern of life. Studying what happened in the past can contribute to this. Through the activities in this section, you will encourage your pupils to think about history as it relates to them. Using group work, inviting visitors into the classroom and using practical hands-on activities to investigate artefacts will allow your pupils to share ideas and develop their historical skills.

1. Discussing artefacts in small groups

Handling artefacts or looking at pictures of them provides a means for you to draw attention to both the factual aspects of history and the interpretation involved. Something that will help you in this work is collecting resources as and when you can. Often it is possible to find old utensils and artefacts from the home and in markets.

This part will help you to plan tasks for your pupils to think about how things that we use in our everyday lives have changed over time. For example, by looking at what we use for cooking now and what we used in the past, we can begin to think about how people used to live. We can compare utensils and, from this, speculate about what it would have been like to live in the past and use such artefacts. This will stimulate pupils’ thinking about themselves and their place in the local community and its history.

Case Study 1: Finding out about objects

Mr Ndomba, a Standard 5 history teacher in Mbinga township, Tanzania, has decided to use artefacts used in farming in his lesson to stimulate pupils’ interest and encourage them to think historically.

He organises the class into groups, giving each group an actual artefact or a picture of one. He asks the groups to look closely at their object or picture and to write as much as they can about it by just looking at it. His pupils do well, as they like discussion, and it is clear to Mr Ndomba that they are interested and enjoying speculating about their artefacts. (See Key Resource: Using group work in your classroom.)

After a few minutes, he asks each group to swap its picture or artefact with that of the next group and do the same exercise again. When they finish, he asks the two groups to join and share their views of the two pictures or artefacts. What do they think the artefacts are? What are they made of? What are they used for? How are they made? They agree on five key points to write about each artefact with one group doing one and the other group the second. Mr Ndoma puts the artefacts on the table with their five key points and makes a display for all to look at for a few days.

At the end of the week, he asks each group to write what they are certain they can say about the object on one side of a piece of paper and on the other side they write things they are not sure about, including any questions. For him, it is not so important that there is agreement on what the object is, but that there is lively, well-argued debate on what it might be used for and how old it might be.

Activity 1: Being a history detective using artefacts

Read Resource 1: Using artefacts in the classroom before you start.

- Ask your class to bring in any traditional objects that they have at home. Tell them that you want the object to be as old as possible, perhaps used by their grandparents or before. But remind them they have to look after it carefully so it is not damaged. Have a table ready to display them on when the pupils bring them in the next day.

- Explain to your pupils that they are going to be like detectives and piece together as much information and evidence as they can about their objects.

- Ask them, in pairs, to look at all the artefacts and try to name each one and make a list of them in their books. Just by looking and holding, ask them to note what they think each is made of, how it is made and what it might be used for. You could devise a sheet for them to use.

As a whole class, look at each artefact in turn and discuss the different ideas. Agree which idea is most popular and ask the person who brought the object in what they know about it. Or send them home with some questions to ask and bring answers back to share with the class the next day.

2. Welcoming visitors to enhance the curriculum

One of the purposes of teaching history to your pupils is to allow them to understand and discover their own and their community’s identity. As a social studies teacher, even of primary school children, you should always be looking for interesting ways of helping pupils understand this past, their history. Considering how local customs, everyday tasks and the objects used for them have changed helps builds this identity.

Case Study 2: Investigating traditional dress

Mrs Okeh has asked two older members of the local community to come to class in their traditional dress and talk about what has changed about traditional dress since they were young.

Before the visit, Mrs Okeh reads Key Resource: Using the local community/environment as a resource and, with her class, prepares for the visit. Once the date and time have been agreed, the pupils devise some questions to ask the visitors about what has changed over time.

On the day of the visit, the classroom is organised and the welcome party goes to meet the visitors. The class is excited but shy with the visitors. However, the visitors are so pleased to come and talk that everyone soon relaxes and there is much discussion about the dress they are wearing and the importance of each piece. The visitors also brought some traditional clothes that belonged to their parents for the children to see.

After the visitors have left, Mrs Okeh asks her pupils what they had learned that they did not know before, and she is surprised and pleased by what they remembered and liked about the event.

Activity 2: Exploring traditional crafts

This activity aims to put in place a frame that you, as a teacher, can use to conduct a classroom discussion about any aspect of social studies or history. In this case, we are looking at local artefacts and their traditional use.

- Arrange for your class to visit a local craftsperson or ask them to come to school to talk with your pupils about their craft now and how it used to be.

- Before the visit, you will need to organise the date and time and what you want to talk about, so the visitor can prepare what to bring.

- Next, with your class, decide what kinds of things they want to know and what questions they would like to ask about the artefacts that the visitor might show them or they might see on their visit. Maybe the visitor could demonstrate their craft for the class.