Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 26 April 2024, 3:16 AM

Week 5: Critical consumption

Introduction

There are often bizarre stories on the internet.

‘Pigeons can identify cancerous tissue on x rays’

‘Why the internet is made of cats’

These are just two stories that have appeared in the media recently. Some are more plausible than others and we’ll be returning later to the question of which are true or not.

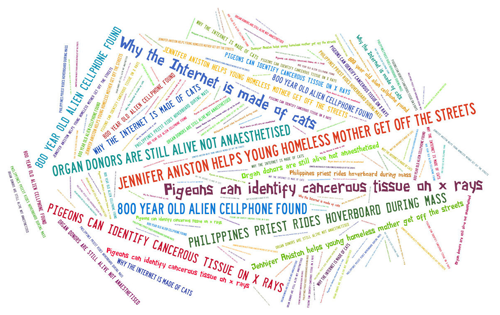

In previous weeks, you have been introduced to the idea of the information age and have explored some of its characteristics. The internet is teeming with information, on every conceivable subject and from many different sources (the image above shows a few headlines that have appeared in the media recently). These sources include an ever-increasing quantity of freely available user-generated information, and from a huge number of online communities. There are advantages and disadvantages to this abundance. It is not hard to find information, but judging its reliability is less straightforward. Online social networks can be very beneficial, but how do you establish whether someone is telling the truth or not?

In Week 4 you considered what you can do to stay safe online and protect your privacy. This week, you will have the opportunity to think about which information sources are most relevant to you in your own context (also referred to as your ‘information landscape’) and learn techniques to deal with

By the end of this week you should:

- have thought about which information sources are most relevant to you

- know how to find reliable information online quickly

- be able to judge how trustworthy online sources are.

1 Your information landscape

You may not have thought of yourself as having an ‘information landscape’. The term is used to refer to the range of information used in everyday life, at work and for study. Everyone is different and therefore information landscapes vary. It is likely that your information landscape will reflect your interests and relate to different parts of your life.

Not every source in your information landscape will be online. For instance, at work your colleagues are likely to be an important source of information. There will be shared understandings about what information means and how it is used in particular workplace settings, for example, healthcare or law. In the activities that follow, you’re going to think about your information landscape as a whole before considering in more detail your online information landscape. This will help you to set the context for your digital life.

The image below includes words describing different categories of information.

This next activity helps you to think about your information landscape, both digital and real-life, and relate the categories of information to different parts of your life.

Activity 1 Getting orientated

Below are four different areas of life, each of which might form part of your information landscape. For each heading, some categories of information are suggested. The list is not exhaustive.

As you read about the categories of information listed under each heading, note down which ones you use in your reflective journal. Are there others, not listed, that you would add? Make a note of these.

When you are ready, you can read the discussion.

You

- Ideas and opinions: your own and those of your family and friends.

- Research: you have done yourself (for example, on the internet).

- Experience: your own, and your family and friends.

Your local community

- News: local newspapers, local television, radio.

- Ideas and opinions: local media and community groups.

- Research: public library (physical or online resources).

- Facts and figures: local library or council, local club meetings and community groups.

- Historical information: archives of local organisations or the local press.

- Experience: local support groups.

Your workplace, college or university

- News: noticeboards, meetings, emails, social media, colleagues, meeting minutes, company intranet.

- Ideas and opinions: colleagues and discussion groups.

- Research: journal articles held in the library, project reports, product test logs.

- Facts and figures: from the information department, or any information systems you have access to, project specifications, orders, contract orders, technical data sheets, product manuals.

- Historical information: notes, records and archives.

- Experience: refer to colleagues, clients and customers, tutors, teachers, and fellow students.

Your world view

- News: the media (newspapers, TV, radio) or the specialist press, social media.

- Ideas and opinions: broadcast media, conferences, information from experts and relevant organisations, social media.

- Research results: national libraries, specialist organisations, relevant journals.

- Facts and figures: national libraries, government statistical services.

- Historical information: records offices and national libraries.

- Experience: national support groups, specialist charities.

Discussion

In practice, most of these information sources exist in digital form. National and international news is generally digital these days and breaking news is often shared on social media such as Twitter or Facebook before it reaches broadcast media.

To use some information sources effectively, especially in more local contexts, a two-way conversation is needed. For example, in the workplace, when asking a work colleague about their experience of a particular job area or issue, you will probably want to clarify and ask further questions depending on the response. This might be by email or in person. Without this clarification, misunderstandings can occur. Information and communication go hand in hand, there is dialogue involved and shared understandings evolve over time.

Information landscapes are therefore not fixed. They change as your circumstances change, as you move into new areas of life and as you engage with new communities. There may be overlap between different parts of your information landscape. In the next activity, you will think about your information landscape and how it has changed.

1.1 Exploring your information landscape

To see what someone’s information landscape might look like in practice, we will hear from Kyaw Win.

Activity 2 Mapping your information landscape

Read what Kyaw Win has to say about the about the sources of information he regularly uses.

“I use Facebook and blogs a lot to keep up with cycling events and get the latest news. I now add my own comments. I stay in contact with my friends through Facebook too. My friends send me funny videos on Facebook which I enjoy and watch on the way to work.

The cost of data used to mean that I couldn’t use the internet much. One way I got round this was to screenshot pages that I wanted to read so that I could read them later. But now I’m working it’s fine and I can follow my interests and develop new interests.

I want to go into marketing so I’ve stared to look at free online courses that I can study alongside my degree. I’ve found some really interesting short courses that are just the right level for me. It’s all free as well.”

Make some notes in your reflective journal about the kinds of areas his information landscape covers.

Now reflect on your own information landscape – what are your most important sources, and how has this changed for you over the last six months?

Use your reflective journal to note key features of your information landscape:

- six months ago

- now.

When you are ready, you may read the discussion.

Discussion

Kyaw Win’s information landscape is mixed and broad. He is involved with his local friends online, but also the wider world through his interest in cycling and blogging. He is broadening his digital landscape to include what can help with his studies and career.

How did your own information landscape compare to that of Kyaw Win? You may have found it includes similar elements, however, it will also be unique to you. You might have found some overlap between different areas of your landscape, for example, your own experience of a particular issue (say, parenting) is reflected in an online community you belong to that is open to people nationally and internationally. You may also have noticed some changes in your information landscape over the last six months. This might reflect changes in your life (for example, starting a new job or course of study), or it could be that other people have introduced you to new sources of information that you find useful.

2 Searching

Now that you have thought about your current information landscape, it is time to look at how you can navigate it. For the following activities, you will use Google to search for information on a topic. You may like to also try using another search engine and comparing the results.

Activity 3 Searching for information on Facebook privacy

- Open Google in a new tab or window and search for information on how to set your privacy options on Facebook. (You may be able to speak instructions for your device to search using a digital

personal assistant such asSiri orCortana , as an alternative to typing it.) - Find two resources: one text explanation and one video explanation.

- For each resource, establish who put the information there, when it was added and how well it seems to match what you are looking for.

- Reflect on the search process you have just been through: what words did you use, and how long did it take you to find the relevant information?

Discussion

A search of this nature will most likely bring back several hundred million results. Text-based resources provided by the Facebook Help Centre will probably appear at the top of this list. This guidance is a sensible place to start, but if you read a bit further down the list, you will find guidance produced by other people. Some of these other resources may give you a more complete view of Facebook privacy settings. Be aware that Facebook changes its appearance and functionality (what users can do) quite frequently, so any guidance more than a few months old may not be accurate anymore.

To find videos, you may have typed the word ‘video’ or ‘YouTube’ or a combination of the two, into the search box, or you may have selected ‘Videos’ from the options at the top of the search screen.

The words ‘Facebook privacy settings’ are enough to bring back the right kind of information. However, bear in mind that in this case it is very important that information is up to date, so adding the current year to your search words may help you get what you want more quickly. It’s likely that you scanned quickly through the results you had found to see which ones looked most promising.

Whether text or video is more useful to you will depend on your personal preference and the topic. Sometimes it can be really helpful to watch a demonstration of what to do, for example, if you want to learn how to do something. At other times written guidance or instructions are preferable.

There is widespread agreement that it is relatively easy to find information online. In fact, information overload is likely to be more of an issue. The problem is not so much finding information in the first place, as in pinpointing the right information quickly. There are a few tricks you can learn to help you feel more in control.

2.1 Refining your search

According to statistics, very few Google searches get past the first page of results. This means that most people accept the first few results they find and don’t go any further. The search you have just carried out may have been sufficient to get you the information you wanted, if it was available on that first page. However, there are some useful techniques for refining your search that will save you time.

In the last activity you may have used Google’s ‘videos’ filter (across the top of the page) to restrict your results to videos. Other information types you can use to filter a search include News, Images, Books, Shopping, Maps and Flights (note that some of these categories may vary depending on the internet browser and version of browser you are using). As well as filtering by information type, it is possible to refine your search in other ways.

The next activity is an opportunity to use some of these techniques.

Activity 4 Refining your search

Some of the following actions will help you to refine your Google search. Read through the list and note those that you think will help you to focus your search more precisely.

Try out the techniques you have chosen and make a note of how successful they were in refining your search.

- Adding more search terms to make your search more specific. Google automatically links your terms together with AND, which means it will search for websites where all your search terms are present. The more specific you are, the more likely you are to find relevant information. Note that the order in which you type your search terms will affect your search results.

- Using ‘OR’ to link your search words. Searching using ‘Facebook OR privacy’ will bring back all websites in which the word ‘Facebook’ is present, and all websites in which the word ‘privacy’ is present (regardless of whether they were about Facebook privacy). If you wanted to find sites in which all these words are present at the same time, you would need to take out ‘OR’ from your search.

- Using quotation marks to enclose your search terms. Also known as a phrase search, this will make your search more precise. For example, ‘complete guide to Facebook privacy settings 2015’. It may exclude some sites you would be interested in though, such as ‘Facebook privacy settings’ or ‘Here’s how to use Facebook’s mystifying privacy settings…’.

- Using an asterisk *. This will expand your search rather than focus it, as it is used as a placeholder for any unknown or wildcard terms. For example, priva* will increase the number or results you find by looking for ‘privacy’ and ‘private’. In this case, it may also bring up organisations named ‘Priva’, which you don’t want.

- Using specialist or specific search terms related to the subject of your search. This can be helpful, especially if you are doing research for academic study. Look for terms used within the field you are researching that help to focus your search more clearly.

Here’s a short video to show you how to focus your search better.

Discussion

Adding or substituting search terms is one way to hone your search. Phrase searching using quotation marks can also be helpful. Knowing the specialist vocabulary used for the subject you are looking for will increase your chances of success. Think about how your subject might be described on the kind of site you are hoping to find. Note that these tips and tricks may not work in other search engines.

Google’s advanced search screen provides a range of options to help you target your search, for example narrowing your search to include specific keywords. You can also filter results to only include those updated within a specific date range or with text in a particular language.

Another option that you may find useful is the option to narrow your search by usage rights to only retrieve resources that are free to use or share.

You can access the advanced screen by going to ‘Settings’ at the bottom of the screen and selecting ‘Advanced search’ – or by googling ‘Google advanced search’. It is worth exploring how the advanced search can help you.

If you really want to get up close and personal with Google, you may like to visit the ‘

Despite being able to refine your searches, you may still find the amount of information overwhelming. You will find out some tips on how to tackle this in the next section.

2.2 Dealing with information overload

Being able to handle information efficiently is a skill which will stand you in good stead, both when studying and at work. Information overload is a very real problem, which can affect morale and well-being if not acknowledged and tackled.

So far, you have looked at the search process and found out how you can refine your search using some of the options in Google. Making full and efficient use of search engine functionality can be a useful tool to help you deal with information overload, but human input is required too. In your initial search, you selected a couple of results. This involved

Filtering is a mental process involving skim-reading, evaluation and a series of quick judgements about what to do next. When faced with a screen full of search results, you can get a feel for which ones might be relevant by looking at the headings, highlighted keywords, type of site, URL and date.

Having decided to investigate a site further, you can get a quick overview by employing some

Scanning involves looking quickly down the page to locate relevant words, phrases or images that you are interested in. This will help you to decide whether you should read further and how useful the website or document might be. You can scan:

- headings and subheadings

- images and artwork

- the body text itself, e.g. for authors’ names

- the sitemap.

Skimming the text quickly involves:

- getting an indication of the scope and content of the information

- looking at the first sentence of each paragraph to see what it’s about

- noting the key points in any summaries.

Of course, information overload is not just about information you find on the web when you are looking for it – it can also come from our inboxes. It is easy to sign up for information from various sites, such as retailers or restaurants, and then find your inbox overflowing with frequent messages that aren’t very useful.

Activity 5 Tackling information overload

Here are some experiences of information overload that people have, with some suggestions on how to deal with it. As you read about their experiences, think about your own situation and make a note of any tips you want to remember. Add these to your reflective journal.

Mon Mon, a parent

“I try to help my children with their homework but it is challenging for me. They are really confident using technology, but they don’t know how to tell what websites are suitable to use for projects or essays. Sometimes they find stuff and the information is just too high level, like for university students.

For myself, I used to find that when I searched Google the amount of results you get is far too many. I couldn’t find the good information in all that. But last week, I was helping Keymar do some research on his geography topic. It was all about river basins in Myanmar which I felt confident about and I found I could advise him how to make his search more exact. That helped in itself. Then when we were looking through the results, I could easily see two or three good sites by scanning the headings and the authors’ names. I also skimmed quickly through the text and the first page to make sure it was the right kind of thing. It was much quicker and I didn’t feel frustrated like I used to.”

Zin Min Thant, a businessman

“My issue was I had so much paperwork to deal with in the office and at home. And then, on top of that, I started finding more and more people were emailing me, which meant my emails were building up too. So after a while, it started to feel unmanageable. I mean, usually I’m quite organised but the electronic stuff was just one step too far. I needed a system for getting to grips with it.

So using the

5 Ds helped me be more decisive. The sheer amount of stuff was getting the better of me. So, I went through my inbox and deleted stuff I knew wasn’t a top priority for me or that I could find out from someone else. And then, there’s a few things that had got buried in there that I realised I had to deal with on the spot, so I did that. And then, some other messages that could wait a day or two, so I flagged them for follow up. Some of it was more relevant to other people than me, so I forwarded those messages. And then, there’s a few messages I just filed for future reference. I felt really good when I’d done that. Now I feel much more in control.”

Banjar, a young chef

“To be honest, I used to get all sorts of stuff come to me through my Facebook feed, and I never questioned it. Because there’s so much coming in all the time, you don’t have time to look at it properly. I’d just see what stories looked fun or entertaining and then share them.

There was one time when I saw a post and it was saying, if you were driving at night and you get eggs thrown at your windscreen, don’t stop the car because you will become a victim of roadside gangs. Well, as a chef I don’ finish work until late and I have seen car crime on my way home, so I thought it must be true and I shared it. But it turned out it was a hoax. So, what I’ve done now is just stop following people and sites that have lots of this kind of stuff. You know? A bit dramatic. Which also means I’ve got less news coming in, and I can see what’s quality or not.”

The 5 Ds (Caunt, 1999) that Zin Min Thant referred to is a useful technique to help you be more decisive when handling information that comes to you. They can be summarised as:

- Discard

- Deal with (Do It Now)

- Determine future action (SIFT it – Schedule It now For Tomorrow)

- Direct / Distribute it (think about why you are directing it and what you expect the recipient to do with it)

- Deposit it (file it).

All the techniques considered so far are part of the broader ability to take a critical stance towards what you read. This is about knowing what questions to ask, so that you can determine not only what information is relevant to you but also who put it there, what their viewpoint might be and how far it can be trusted.

Critical thinking is a skill of great value not only for academic study but also for life in general. It will also help you to stay in control of your digital life, rather than feeling it is controlling you. In fact, it is probably the number one skill you can develop.

3 Asking the right questions

In December 2015, a new article posted on Facebook claimed that ‘a single eruption from a volcano puts more than 10,000 times the amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than all of mankind has produced’. On the face of it, this is a plausible statement. However, it is actually false. The estimated annual amount of CO2 generated by human activity is 135 times higher than the annual amount released by volcanoes (Snopes.com, 2015).

Have you ever been convinced by information that later turned out to be untrue? Maybe you even passed it on to someone else, believing it came from a reliable source? Some stories and videos on the internet are clearly untrue but in other cases, it may not be so clear-cut and you are unsure whether to believe what you see or hear. Sometimes this may not matter. However, if government policy decisions or guidance to citizens were to be based on faulty information, there could be serious consequences. But how can you know what is reliable or not?

It helps to know what questions to ask of what you read or see or hear online. There are various frameworks that provide you with a good starting point. Here are two that The Open University has come up with,

CAN I trust this information?

C – Credibility: How much do you know about the person or organisation providing the information? What sort of authority do they have for any statements or opinions they put forward? How do they back up opinions or facts? What sort of language do they use? Language that is either emotionally charged or vague can be a danger sign.

A – Agenda: Can you detect any bias or agenda? Who has put the information there? Do the authors state clearly the viewpoint they are taking? Can you detect any vested interests, for example, a particular political viewpoint or a product that is being promoted? You may need to dig deep to uncover these: this could include scrutinising the ‘About’ information on the website, and doing some research to find out more about the organisation or people who put the information there.

N – Need: What is your need or requirement in this particular situation? Think about what you are planning to do with the information. How important is it that the source is trustworthy?

This framework is useful for the sort of quick evaluation you might do in everyday life. It reminds you that the extent to which you scrutinise an information source may depend on what you plan to do with it. Sometimes, you just want a quick idea of what a topic is about, or a sense of what others thought about something you are interested in (e.g. a place you want to visit or when you want to buy a new phone). Wikipedia is one source that many people use to get a quick overview. Social media is also a source of news and information. Use the set of questions above to do a quick reality-check, for example, when someone shares a sensational sounding story on Facebook. Ask CAN I trust this?

PROMPT – evaluating information

P – Presentation: Is this information clear and well-communicated? Is it succinct? Can I find what I need here? If it’s a website, is it easy to use and navigate?

R – Relevance: Does this information match my needs right now? What is it mostly about?

O – Objectivity: Are opinions expressed? Are there sponsors? What are you being ‘sold’ here (a particular product, or corporate view)? What are the vested interests or hidden agendas?

M – Method: If statistical data is presented, what is this based on? How was the data gathered? Was the sample used really representative? Were the methods appropriate, rigorous, etc.?

P – Provenance: Is it clear who produced this information? Where does it come from? Whose opinions are these? Are they a recognised expert in their field? Do you trust this information?

T – Timeliness: Is this current? When was it written and produced? Has the climate or situation changed since this information was made available? Is it still up to date enough?

The PROMPT framework offers a structured method for evaluating any information you find online. It is more detailed than CAN, and is especially useful when studying, for example, if you are looking for trustworthy sources to support arguments in an assignment. You can use it to evaluate both academic articles and freely available information on the internet. It can also be very helpful in a work environment, for example, if you need to find material for a project or report. Rigorous evaluation is particularly crucial when business decisions are being made on the basis of information you provide. You may not need to go through the whole checklist each time you evaluate something, but it provides a useful reminder of what to look for. With practice over time, you will find that asking these kinds of questions becomes second nature.

You can download the CAN and PROMPT checklist to refer to later.

In the next activity you will think about how far you already ask critical questions of the online sources you come across in your ‘information landscape’.

Activity 6 Evaluating resources

Identify some situations where you have needed to find information on the internet.

How do you decide what to trust?

Note down the sort of process you go through and the questions you ask. How far do they reflect the CAN or PROMPT criteria?

Record in your reflective journal any points you want to remember for the future.

Both these frameworks can be used and adapted for all kinds of information. You can also use them when deciding who to trust online. While your ‘gut reaction’ should not be ignored, it is good to go beyond initial first impressions of how a person comes across online. It is worthwhile doing a search to find out more about their background, who they are linked with (for example, particular professional or political groups) and what they do and say online. Many employers do an online search when considering whether to interview or appoint someone.

3.1 Useful starting points

Although using a general search engine such as Google may sometimes be the best approach when looking for resources online, there are other alternative starting points that can save you time.

These include:

- freely available online resources

- resources available via subscription

- specialist search engines

- social networks.

Of freely available resources, some are produced by organisations such as universities and may be licensed under Creative Commons for anyone to use, share and (sometimes) adapt. Others are contributed by individuals or created by members of online communities.

Freely available resources

Wikipedia is a well-known example of a freely available resource created by many different people. When searching for information on the web, you will often find that references to Wikipedia articles appear near the top of your list of results. Opinions on Wikipedia are often divided, as many people are sceptical about the quality of information held there. The best advice when assessing the accuracy of an article is to find out about the author and look at the references listed at the end. You could also keep an eye out for who has edited the page, how many times it has been edited and any conflicting agendas on the part of the editors. You can find this out by clicking on the ‘View history’ tab of any Wikipedia entry. Wikipedia is useful for getting a quick overview of a topic, but it is always wise to double-check what you find against other sources.

If you are looking for a particular type of media, you may find it useful to go to a site that brings those resources together. Some examples include YouTube for videos, Flickr for photographs, SoundCloud for music and podcasts, and the onlinenewspapers.com site which provides access to newspapers from around the world. It is often possible to interact with others on these sites by commenting on, rating, sharing or liking resources.

Open Educational Resources (OERs) have already been mentioned. This course is an example of an OER on the OU’s OpenLearn platform. The OER Commons network lists a large number of OERs provided by many people around the world.

The Open University Library also provides a list of good-quality freely available online resources that anyone can use. These resources cover a wide range of subject areas and are worth exploring if you have time.

Subscription resources

An important resource for students doing degree courses is their college or university library. Myanmar students and academics may have to depend on online resources such as Google scholar and Research Gate -some are free and some paid- to search for academic papers and books.

It is also possible to take out your own individual subscription to online journals and magazines for a fee.

Specialist search engines

Specialist search engines can be useful. For example, Google Scholar is useful for tracking down academic articles and books, though the results aren’t always comprehensive, and the full text is not always freely available.

Online social networks

Online social and professional networks can be useful resources for information research. LinkedIn is one example. Not only can you put your own profile and CV on there, but you can also find other people in the field you are interested in, identify potential jobs and learn from the discussions that happen in special interest groups. Some online networks are informal, such as Facebook groups set up by groups of professionals and trades people, to support each other. Facebook helps particular communities such as small businesses, professionals and civil society in their networking and communication. For many in Myanmar, Facebook is Google, LinkedIn, Tinder, Tumblr, and Reddit, all in one. Universities have many such groups for students and staff.

3.2 Developing your ‘trustometer’

Often, you are taking a calculated risk when deciding whether to trust someone or something online. What you decide to do may depend on how much time you have available and what is at stake. Developing your research and evaluation skills will enable you to weigh up the ‘pros and cons’ more quickly and make good decisions. You could think of the decision-making process as your ‘trustometer’. A ‘trustometer’ is like a barometer. A barometer helps you read the weather. A ‘trustometer’ helps you read whether the site can be trusted and the information provided relied upon as being accurate. You are now going to put some of what you have learned into practice.

Activity 7 What would you do?

Mon Mon, Zin Min Thant, and Banyar are facing some predicaments in their digital life. Read what they have to say and note down the advice you would give to each one of them in your reflective journal.

Mon Mon, Myanmar parent

“My husband was recently diagnosed with coeliac disease. I didn’t know much about this disease, so I read a lot of articles about it online. But they say different things. Some make me feel hopeful, but others depress me. How do I know what to believe?”

Zin Min Thant, Myanmar businessperson

“I’ve been a victim of a banking scam through an email. They said that they were from my bank and they asked me to verify all my account details. There was a link to a website where I had to enter my pin number. I was really busy at the time so, unfortunately, I didn’t read the email too closely.

I was new to internet banking and it all looked so convincing, so I followed all the instructions. Later, I found out that they had taken money out of my account. My bank helped me sort it out, but how could I have avoided this happening?”

Banjar, Myanmar chef

“I love to cook and I’m passionate about using fresh ingredients in cooking, I’ve started a blog about Shan cuisine to share my love of Shan cooking. Recently, in one of my posts, I included a photograph I’d found on the web of Yadana Man Aung Su Taung Pyay Pagoda in Shan State, and someone contacted me and asked me to remove it because they held the copyright. It’s so difficult to tell what you can and can’t use. How could I have found something that I could have used legally and for free?”

Discussion

Mon Mon could have used the PROMPT framework to help ask questions about the provenance and accuracy of some of the articles she read on coeliac disease.

Zin Min Thant now knows that his bank would never ask for his PIN by email in this way. The site that he was taken to looked convincing and professional. However, on closer examination the URL was not quite right. The email itself began ‘Dear Sir or madam’ and contained several grammatical and spelling errors, which would not have occurred in a real communication from the bank, as these are usually carefully proof-read. A useful site that lists scams and hoaxes to be aware of is Hoax Slayer.

Banjar could have done an image search using the ‘Usage rights’ filter in Google advanced search, to search for images that are free to use or share. Or he might have found something suitable in an online collection of images licensed under Creative Commons, such as Flickr.

4 Reflection

During this week you have been learning how to ask the right questions and develop a critical mind-set towards what you read online.

Activity 8 Asking the right questions

Have a go at evaluating one or both of the stories below using the techniques you have been introduced to. (Look back at Section 3 Asking the right questions if you need a reminder).

Scan the article to get a feel for the headlines and key points of the story. Make a note of the process you follow in each case and any questions that arise in your reflective journal. For example, how do you decide if someone is who they say they are? If scientific claims are being made, how can you check what they are based on?

- Article 1: Pigeons can identify cancerous tissue on x-rays… (Brait, 2015) (or watch the YouTube clip: Pigeons as Trainable Observers of Pathology and Radiology Breast Cancer Images(2015).

- Article 2: Why the internet is made of cats (Potts, 2014). There is no need to read the whole article, the section entitled ‘Allen-Alchian Explains Why the Internet is Made of Cats’ and the conclusion should give you enough to go on.

Discussion

The story about pigeons being able to identify cancerous cells is based on bona fide scientific experiments. For some of the research behind the headline see Pigeons as Trainable Observers of Pathology and Radiology Breast Cancer Images from Plos.

‘The birds proved to have a remarkable ability to distinguish benign from malignant human breast histopathology after training with differential food reinforcement; even more importantly, the pigeons were able to generalize what they had learned when confronted with novel image sets.’

Article 2 argues that ‘cute shapes the internet’ (with particular reference to Grumpy Cat). The author uses the Allen-Alchian theorem, or the ‘third law of demand’ to model quality on the internet.

The article makes some assumptions, which may make sense to those immersed in the field of economics but are open to question from other perspectives. It is up to you if you buy the argument or not!

Add to your reflective journal one or two top tips for evaluating information that you would like to remember. Also make a note of any ways in which your information landscape has changed as a result of what you have learned, for example, useful new sources or networks you have discovered.

Here are Kyaw Win’s reflection on the week:

“I thought about the information sources that I use most, and also practiced developing my searching skills. I think this will save me a lot of time and frustration in the future. It’ll also mean I’m less likely to get information overload.

Practicing this also developed my critical skills. This will be useful in my degree studies as well as my digital life because I have a better idea what the right questions to ask are. Sometimes opinion is presented as fact and it’s not always clear. Take the example of mining companies in Myanmar and the environment. You’ll get very different views from a mining company website to an online environmentalist about the impact of mining on the environment.”

5 This week’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this week by taking the end-of-week quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’ve finished.

6 Summary

This week you have focused on your information landscape and how to navigate it. You have been introduced to:

- some ways of finding information quickly

- some approaches to dealing with information overload

- criteria for judging who and what can be trusted

- some useful starting points when searching for information.

You have learned how to:

- search effectively

- filter, scan and skim to get to the information you want more quickly

- ask the right questions of online sources.

You have had the opportunity to put what you have learned into practice using real-life scenarios and stories that have appeared in the media.

The key point from this week is the importance of thinking critically about sources of information, whether online or not. The relevance of all this to the workplace has been highlighted throughout.

Week 6 will continue with the theme of how to make technology work for you rather than you for it. As part of this you will have the opportunity to use your critical thinking skills to evaluate online tools and

You can now go to Week 6.