Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 10 March 2026, 6:35 AM

Week 1: Teaching online is different

Introduction

Welcome to Take your teaching online (part 1)! In this first week of the course, we will introduce some of the key differences between teaching online and teaching in a face-to-face environment. These differences mean that teaching online is a substantially different experience to teaching face-to-face, with a substantially different skillset needed for the teacher. The good news is that most teachers can adapt not only their face-to-face teaching skills, but also many of their existing teaching materials, to suit an online environment. There are a lot of possibilities, but as a minimum, if you have a computer and your students have a mobile/tablet or computer and can access to the internet, then you can start to teach and learn online.

In this week, you will also meet Rita, our animated colleague who is working her way through this course alongside you. Please allow Rita to introduce herself and to outline what she hopes to get from this course.

Transcript

Rita is a teacher who will be working through this course alongside you. She is, like you, interested in teaching in different ways and learning how to teach more effectively and inclusively, and how technology can play a part in that.

Rita is a good teacher, she is quite confident in the classroom, and she likes to use images and sometimes videos in her teaching to keep the students interested. One of her long-term teaching objectives is to deliver some teaching online. She is not sure if this will be possible as part of her current job at her current university, but maybe sometime in the future it could be, or she may wish to change to a new job that includes online teaching.

Rita is hoping that studying this course will help her to learn about online teaching and enable her to pursue this goal of delivering teaching online in the near future.

Every week of this course we will catch up with Rita and how she is doing, as a prompt for you to think about your own teaching practice and development, and what you have learned in each week of this course.

By the end of this week, you should be able to:

- discuss the main characteristics of online education activities and how these differ from face-to-face teaching

- begin to determine the kinds of face-to-face teaching activities that might, or might not, transfer successfully to an online environment

- summarise the elements of online teaching that need a different skillset to face-to-face teaching.

1 Synchronous and asynchronous modes of teaching

One of the most common ways to think about teaching online is to consider whether it might be synchronous, asynchronous, or a mixture of both.

Synchronous teaching

The teacher’s role in online synchronous teaching might not be so very different from their role in the face-to-face environment. Synchronous learning may feature webinars (live online lessons), group chats, or drop-in sessions where teachers are available to help at a particular time. However, teaching synchronously online will require some new skills to be developed, for example in managing the faster pace of teaching.

If a course is delivered entirely through synchronous teaching, face-to-face or online, this can limit flexibility for learners. Because of the need for everyone to be present at the same time (even if online), all students must work through the course at a similar pace, allowing only minimal flexibility in scheduling. As everyone needs to be online together, if a learner is not available for a lesson, they miss it (although some teachers or learning organisations will record lessons for these students to view later).

Synchronous teaching is where the teacher is present at the same time as the learner(s). This is almost always the case in a face-to-face environment. Synchronous teaching can also take place via online learning, through the use of video conferencing and live chat or instant messaging. As with the face-to-face environment, the learners in synchronous online teaching can ask questions in real time.

Asynchronous online teaching

Asynchronous online teaching is where teaching materials are posted online, and learners work through them in their own time, communicating with each other and the teacher via discussion boards or forums, or by email. Good asynchronous teaching will include a variety of media, including (but not limited to) audio and video clips. With an asynchronous mode of teaching, the learner can work at their own pace and at times of day which are convenient for them. The teacher may find that the pattern of their input is very different from the synchronous environment, with many shorter visits to the discussion boards or forums being more valuable to the learners than one single, longer session. There may still be deadlines for work to be submitted for feedback, and there may be a recommended schedule for students to follow so that they have some idea of what they should be doing and when. As you will discover later in this week, a ‘blended’ approach can help teachers to bring together the advantages of synchronous and asynchronous teaching, and of online and face-to-face teaching, into a single experience.

The importance of collaboration

Collaboration between students, and between students and teachers, is an important factor in both synchronous and asynchronous online teaching, helping to create a sense of connection between all participants and to build a sense of community and shared purpose.

Collaboration in a synchronous environment can be achieved in much the same way as in a face-to face-classroom, with discussions and group tasks. In the asynchronous environment, collaboration can be trickier but is still very important in reducing the sense of isolation learners may feel when working online. Discussions and group tasks can work just as well asynchronously as synchronously. Indeed, because of the lack of time constraints, learners can spend time composing a quality response when contributing to an asynchronous online discussion.

1.1 Teacher reflections

Every week we will present case studies by teachers who have moved their teaching online. This provides you with a real world experience related to each week’s material. At the same time, this also highlights how simple video clips can be produced and used for online teaching purposes.

This week we have Dr. Myo Aung. His experiences reflect a few of the concepts we introduce this week and will discuss further in the weeks to come:

“My name is Dr. Myo Aung and I am a chemistry teacher. I have worked at one of the established universities for over four years and I teach several hundred second and third year students. I want to tell you today about how I started to move my teaching online. After completing several courses delivered online about online education, I started adopting some online elements in my teaching. It seems to be going well, and I want to have some conversations with the university about expanding these online elements.

My university has been trialling online synchronous classes and I have been part of this trial. So the students all log in at the same time as I do, and we have a class, all together, in real time. Within the software we are using, the students can see my prepared slides, they can hear me talking, and there is a setting that I can choose to allow them to speak to me and to each other. I have been experimenting with allowing them to speak at all times, or only at times that I permit them to do so. The software also has a whiteboard tool, to enable me to draw on the screen and annotate my slides, and I can also pass control of this to the students to allow them to, for example, tick boxes on the screen or place data points on a graph. Some of the students do not have a microphone, or more often are in places where they cannot speak loudly, such as computer labs or even workplaces, so we also have a chat facility enabled in the software that allows them to type messages to me and to each other. They tend to use this quite formally, there is not much ‘frivolous’ or ‘social’ chat apart from saying hello to each other at the start and goodbye at the end.

I set them tasks during the online synchronous session for them to do in their own time before the next class, just as I would do in a physical classroom. At the moment I sometimes ask them to email me their work, but hopefully soon the university will have an automated system where the students can submit their work online and it will come through to me after being logged in the ‘system’. This will help me as I could download all the students’ work in one big batch and take them home to mark, rather than getting emails at all times of day and having to remember to save the work into a particular folder to download before I go home - an automated system will be more reliable than my memory!

One of the main advantages the students have reported about the online sessions is that they can watch the recording again after the synchronous session, so they can cover and re-cover difficult topics until they are sure they understand it. Usually the tasks I give them to complete are based around developing this thorough understanding of one of the core topics.

One big advantage that I had not previously thought about was revealed to me a few months ago. One of my colleagues in the chemistry department was involved in a vehicle accident and required to take two whole months off work. During that period I could invite his students to attend my online classes without any difficulty (it would have been difficult to find space for them in the physical classroom) and several other tutors who have been involved in the online teaching experiment also did the same. These students also had access to the recordings of the synchronous sessions. So they were not really disadvantaged much by their teacher’s absence. And when my colleague was starting to become well again and returned to work, he was able to deliver his lessons online on occasions when he felt too weak to attend the classroom.

If you are thinking of moving your teaching online, I would definitely say you should try it. It requires some learning, and your teaching and methods need to be adapted to some extent, but the advantages to your students are really numerous.”

1.2 Making use of asynchronous and synchronous online teaching opportunities

Throughout this course you’ll be introduced to research papers relating to the topics discussed. The first such paper, by Murphy, Rodriguez-Manzanares and Barbour (2011), reports on interviews with 42 Canadian high school distance education teachers regarding their views on synchronous and asynchronous online teaching activities. The authors found that:

- The teachers used different combinations of synchronous and asynchronous online teaching. Some taught entirely asynchronously. Others combined asynchronous teaching with synchronous forms such as scheduled classes or times where they would be available for tutoring and responding to students.

- All those interviewed made some use of asynchronous online teaching, such as providing learning materials for students to work through in their own time, use of online quizzes, or supporting students to ask a question via email or forums and receive a response at a later time.

- Teachers suggested that asynchronous and text forms of communication were preferred by many students. One suggested that it was rare for students to request voice chat rather than text communications, another noted that students could email to ask multiple questions and the teacher could then take some time to construct a response.

- There were also perceived advantages to synchronous modes of communication. Some teachers felt that addressing a particular problem or query raised by a student would be best achieved through videoconferencing or the use of a shared online whiteboard. It was also felt that opportunities for synchronous online teaching could help the students to feel less isolated, because they could include time for socialising and informal discussion.

Activity 1 Thinking about synchronous and asynchronous online teaching

Having read this section and the vignette about Dr. Myo Aung’s experiences, think about how synchronous and asynchronous modes of online teaching could be applied to your work.

Try to come up with three short examples that fit the following situations. These could be based on your own experiences of teaching or learning, or a situation that you can imagine:

- A situation where synchronous learning is appropriate and beneficial in supporting learning.

- A situation where asynchronous learning is appropriate and beneficial in supporting learning.

- A situation that combines synchronous and asynchronous learning to support learning.

Discussion

This activity is designed to help you begin to think about online teaching in your own context. One of the very first considerations in taking teaching online is to decide which elements lend themselves to synchronous learning, asynchronous learning, or both.

The study by Murphy, Rodriguez-Manzanares and Barbour (2011) was conducted in a particular context: High school distance education. Some of the findings may hold true for you, but they may not be universally applicable to all students in all courses.

It could be helpful to think about the practical issues, the preferences, and the benefits in your own case. For example, there could be very good practical reasons for using an asynchronous approach with your students, such as the expectations that learners will be engaging at different times. But it might be that a synchronous mode of instruction is beneficial because it offers a more immediate chance to understand and address queries. Preferences might vary and could be gathered from students if there is uncertainty about the best approach. Some students may like the way a synchronous discussion allows you to create a sense of community and engagement. Others may prefer the slower pace of an asynchronous activity where they can craft a question or response in their own time and reflect on it before sharing with others.

It is often sensible to make use of both forms of teaching to provide a range of experiences and opportunities for learning.

1.3 Interacting with students

One of the most noticeable differences between synchronous and asynchronous teaching is the nature of the interactions between teacher and students. Such interactions include providing feedback, answering questions, or guiding students through a particular activity.

Focusing on feedback, in a synchronous teaching environment, the teacher can deliver feedback immediately whenever it is required. However, while the face-to-face environment allows for visual cues when delivering feedback, these are not always possible in the online environment. It is important when teaching online to proactively make opportunities for feedback both from teacher to learner and from learner to teacher, to make up for the loss of the face-to-face cues.

Feedback in the asynchronous environment will be given some time after a learner has asked a question. So, if several iterations of the conversation are needed to help the learner with their issue, it can take some time to give the feedback. This is one of the reasons why peer feedback is often used in the asynchronous setting, allowing learners to aid each other without having to wait for the next input by the teacher (Gikandi and Morrow, 2016).

1.4 Motivation, support and discipline

Keeping learners motivated and attentive online can be much more challenging than in a face-to-face environment where your personal enthusiasm for the subject can readily rub off on the learners. In an online environment, you will likely have learners who are more self-motivated, learners who are more comfortable with online learning, and learners who are less certain of how to interact in an online learning environment. There might be particular challenges for those learners who are less capable of structuring their studies independently or lack digital skills.

To keep learners motivated and confident it is worth providing a highly structured set of tasks in the opening stages of the course, with discrete outputs, which enable you to see very quickly which learners are completing the tasks on schedule and in the manner that you desire. You can then follow up individually with those who are not engaging in the expected manner and offer advice on how they should approach the tasks and their online learning experience.

On the other hand, maintaining control of a class online can be more straightforward than doing so face-to-face. In the face-to-face classroom, individual learners can disrupt the lesson or distract other learners, but the online environment is different. During synchronous events, you can combine existing classroom skills with the features of the environment (such as the teacher controlling whose microphone and screen sharing is enabled at any given time) to avoid any one learner dominating discussions. In asynchronous discussions, inappropriate or tangential comments can be moderated or, if appropriate, challenged publicly, as with a face-to-face teaching setting.

A further difference with respect to discipline in the online learning environment is the possibility for interactions outside of the channels that you are present in. We will talk about the concept of ‘backchannels’ later in this week. When teaching online, educators need to always be aware that interactions may be occurring between learners in places that are out of your reach, and the possibility for misbehaviour or conflicts between students. Bullying, for example, needs to be borne in mind. If a learner is unusually reticent in an online session, or doesn’t post to a discussion thread which you would have expected them to engage in, it can be worth tactfully exploring with the learner (in private, of course) to ascertain what has caused the change in their interaction/behaviour online.

1.5 Developing skills and confidence

It is important to note that supporting learners in an online environment requires a different skillset to supporting learners in a face-to-face learning environment. A study by Price et al. (2007) into the differences between learner perceptions of teaching in an online environment and in a face-to-face environment found that the online teacher should have a greater pastoral focus than that of a face-to-face teacher, and that often both teachers and learners needed guidance and training in communicating online.

Without the ‘comfort’ of a physical classroom environment, learners can feel isolated and unsupported, so an increased pastoral presence by the teacher, initiated via online communications, can help reduce that feeling of isolation and develop a more ‘comfortable’ experience for the learner. A large scale, follow-up study by one of Price’s co-authors (Richardson, 2009) which looked at the experiences of learners receiving tutorial support online or face-to-face on humanities courses, concluded that with adequate preparation, the online environment need not be a lesser experience for learners in terms of support: ‘Provided that tutors and students receive appropriate training and support, course designers in the humanities can be confident about introducing online forms of tutorial support in campus-based or distance education.’ (pg. 69)

If you are moving into the online environment with your teaching, you also need to be aware of the complexities that technology may bring. Whilst it is not usually necessary to become a technical expert, familiarity with the common technical issues your learners may face can be a very useful skillset to develop. If, for example, you can advise on the common techniques to resolve audio issues during synchronous online sessions, you can both save time and stress for learners and build their confidence. Your confidence to approach new technologies and to deal with issues that arise in their usage will grow as you gain experience and this makes teaching online a much more pleasurable experience. So set aside some time to play and familiarise yourself with the tools and delivery platforms you expect to use. Also, it is always worth finding out whether there are training or development opportunities focused on the specific online teaching technologies that you expect to use.

Activity 2 Motivating and engaging students online

- Watch this video ‘Engaging and motivating students’ or read the transcript of the video which summarises views from a range of experts on student engagement.

- As you watch or read, make notes or highlight any useful tips that you would like to incorporate into your own online teaching.

Transcript

Week 1, Activity 2, Transcript: Engaging and motivating students

The Importance of Teacher Presence

Creating a Learning Community

Strategies for Motivating Students

Sustaining Participation and Engagement

Discussion

Teaching online brings many opportunities to use different tools and techniques with your learners.

This activity should help you to begin thinking, in broad terms at this stage, about what you might like to try. The upcoming activities will look to develop your ideas further and guide you towards means of trying them out in practice. More on that to come!

2 Blended learning

Previously, we introduced the distinctions between asynchronous and synchronous teaching. Another concept that might be very useful to help you understand how to teach online is blended learning. Blended learning usually refers to a course that includes both online and face-to-face elements.

A blended approach will usually bring together three core elements: classroom-based activities with the teacher present; online learning materials (which may be used in different ways – as you'll see in the section on ‘flipped learning’); independent study using materials provided by the teacher, either online or in hard copy, to reinforce concepts or develop skills. This blend of activities means that the teacher also has a blend of roles, adding a ‘facilitator’ element to their role as they organise and direct group activities, both online and offline.

Blended learning can help to bring together the main advantages of synchronous learning:

- teacher presence

- immediate feedback

- peer interaction.

It can combine these with the main advantages of asynchronous learning:

- independence

- flexibility

- self-pacing.

It can help to avoid the pitfalls of asynchronous learning:

- learner isolation

- difficulty with motivation.

2.1 Flipped classrooms

‘Flipped classrooms’ utilise the blended learning model to reverse the traditional learning environment such that the learners receive the bulk of the instructional content online. Learners would, for example, be asked to understand and process a set of material in their own time and at their own pace. This would take the place of more traditional post-class ‘homework’ tasks. The classroom sessions are then used for interactive discussion and exploration of the topic with the teacher, which takes the place of the more traditional instructional scenario. Hence the type of activities undertaken in each context is the reverse of what is usual. The class has ‘flipped’ to be the space for students and teachers to be more active, engaging with each other in a more personalised and focused way. The online environment then becomes the home for the more traditional lecture-style teaching.

Activity 3 Thinking about the flipped classroom

This video synthesises the benefit of a flipped classroom approach.

Watch the video and note down three benefits of the flipped classroom over a traditional approach.

Discussion

This activity is intended to introduce you to the concept of the flipped classroom approach, and to help you to identify the benefits it may have in your own context.

The benefits suggested for the flipped classroom approach include the ability for students to work through materials at a pace that suits them, and a reduction in boredom for students who are finding the material easier. The teacher can spend class time addressing individual needs.

There is a wider theme that can be found in this video and elsewhere in this course. This is the way that the role of a teacher can change in response to a change in approach using technology. In the case of the flipped classroom, the teacher is seen to become more of a ‘coach, mentor and guide’, rather than acting primarily to deliver knowledge. You might see this as a benefit, depending on your point of view on what the role of a teacher should be!

Now that you’ve been introduced to some of the unique aspects of online teaching, the differences between synchronous and asynchronous elements, the possibilities of blended learning and the notion of the flipped classroom, the next activity prompts you to reflect on your own practice and how it might fit with what you have learned so far.

Activity 4 Starting to build your plans for teaching online

This activity asks you to reflect upon what it is that you would like to achieve in terms of online teaching. Now that you have read a little about the basics of teaching online, think about what your goals are in this area. You may not have specific goals in mind yet. If you don’t, simply focus on one course that you teach and consider how it might be moved wholly or partially online. Note down answers to the following questions if you can:

- What course(s) do you want to deliver online? Do you aim to transfer online a small or substantial element of what you currently deliver face-to-face? Will you move entirely online or create a blended approach? Will you use synchronous or asynchronous activities – or both? Might a flipped classroom approach be appropriate?

- To whom do you want to deliver the learning experience? What level of digital skills do your intended learners have? What level of experience with online learning is likely amongst your intended learners? What support might your learners need to make a successful transition to online learning?

- What resources do you already have that you might be able to repurpose for online learning?

Record your responses below and, if you wish, in your own journal as you will revisit them later in this course.

Discussion

This is the first in a series of activities that appear throughout this course, helping you to develop a plan for taking your teaching online. This first step will give your plans a starting point. You may find it helpful at this stage to keep a range of options available, perhaps listing several ideas for each point. You could narrow these down to a single plan a little later.

3 Learner anonymity, backchannels and social interactions

In some online teaching environments, all interactions through ‘official’ channels will be obviously attributable to individual students. Forum posts will usually only be possible from students’ institutional online accounts, and therefore their name will be attached to everything they contribute. Similarly, login information for synchronous online events will usually be provided by the institution and will identify each learner clearly. However, there may be circumstances where this kind of information is not provided by default, and learners can choose to create accounts that do not identify who they are. Such anonymity can have a great advantage for more reticent learners who may be reluctant to contribute under their own name for fear of giving an incorrect answer, for example, and can be very enabling for the entire cohort if discussing very sensitive topics. However, it can also embolden trouble-makers or more dominant personalities, and because of this it can be challenging for the teacher to moderate activities where the interactions are anonymous.

As you learned earlier in this week, any online teaching activity carries the possibility of interactions developing between learners in spaces away from the official locations for the online learning. Whilst there can be concerns about the lack of control over these communications between learners, more often they can be exceptionally useful to learners (Fiester and Green, 2016). If students are in touch with each other via an instant messaging app, for example, during a synchronous online learning event, they can often help each other with understanding the issues covered without having to declare in front of the teacher that they need assistance. This can lead to a greater collective advance in learning than would happen if only the official channels were used.

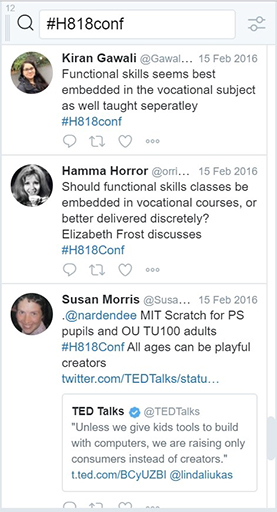

It is important to consider how we as educators can encourage and structure effective use of backchannels. One example of backchannels being used to great effect is the use of Twitter and a dedicated hashtag to synthesise and discuss presentations during a conference (be it online or face-to-face). This image shows some of the use of the hashtag #H818conf during the H818 Online Conference 2016, an annual event ran as part of one of the modules of The Open University’s MA in Online and Distance Education.

4 This week’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this week by taking the end-of-week quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’re done.

Summary

This week you’ve been introduced to some of the core concepts in online teaching. Synchronous and asynchronous activities are a key distinction in teaching online, and deciding which activities or resources should be used synchronously and which asynchronously is one of the fundamental skills any online teacher must develop. Blended learning and flipped classroom techniques could become a fundamental part of thinking for teachers whose classes are divided between a face-to-face element and an online element. We will move on next week to looking at what makes effective online teaching and how education theories can inform how we approach online teaching. Before we move on, however, let’s have a few moments with Rita, to see how she’s getting on.

Transcript

After studying Week 1 of this course, Rita thinks that she has now identified what it is that she wants to do as a result of studying this course. She wants to try to move a whole course online, that she currently teaches in a classroom. She teaches this course to one cohort of undergraduates, three times a week, for one hour each time, for 12 weeks, so that is 36 hours of teaching activity to move online.

One of the reasons for trying this, is that her Friday classes are poorly attended by students, and she spends much time in the Monday classes recapping what they missed. Part of the reason for the low attendance is that the students have only this one class on a Friday, and so travelling into the university and home again just for one lesson is expensive in time and money for the students. Even though some students do not have internet access at home, the online sessions can be recorded. So the students who still have to miss the Friday online class could watch the recording on campus on Monday morning, before the next class takes place on Monday afternoon. This will also benefit those students who have other commitments such as jobs, as they will be able to watch the lessons at times that are convenient to them.

What Rita aims to achieve is to reorganise her teaching materials for this course, so that she can try to use a ‘flipped learning’ approach, setting tasks for the students to learn about before the next class. She realises that this will need a blend of synchronous and asynchronous activities.

Rita realises that the most effective method may in fact be to take a ‘blended learning approach’ by making her Friday classes online and her Monday and Thursday classes face-to-face. But she really wants to explore the power of online learning first, before considering a blended approach.

Rita has talked with her colleagues and manager about this. They are supportive, but it is clear she will be doing this alone as an ‘experiment’ to see if it could be more widely adopted. If it is successful, she may be asked to train her colleagues. Her learners are very positive about the idea, because of the flexibility for them, but some are worried about the lack of sessions in a physical classroom (some of them do not realise that a synchronous online session is not a lot different to a classroom lesson).

Now that Rita has her idea, she needs to know what underpins online teaching, how to make it happen, and which tools to consider using, and that’s what we will move onto next.

You can now go to Week 2.