Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 21 November 2025, 7:16 AM

Week 2: Discovering the connections: principles and theories for understanding digital tools

Introduction

How do you get started with online teaching? In this week, we will look at some principles that underpin effective online teaching, and how learning theories can inform approaches to teaching. Following this you will be introduced to a categorisation of the technologies used in online teaching. Finally, you will be introduced to the world of learning objects. Pulling all of this together should enable you to start planning what you want to achieve with online teaching.

Teacher reflections

“Hello – I am Dr. Su Myat. I have been a geography lecturer for 23 years, so I am very familiar with the classroom environment! However, I have seen a lot of changes in my students over the years, and their interest in technology has never been higher. I encourage them to use their phones in the classroom to use Google Maps for researching various topics. I also hear younger staff members (especially those involved in the TIDE project!) talking about online materials - it was some of these colleagues that first introduced me to the idea of creating online educational resources.

When I first started creating online learning materials for my own use with my students, I was surprised at the amount of time that it took. Compared to my previous face-to-face teaching experiences, I had to dramatically change the way in which I planned for learning opportunities when taking them online. I quickly realised that the ability that you have in class to change the direction of the lesson and to quickly adapt to the needs of learners didn't exist, so much more thought about the different routes that students could take needed to be considered in advance.

Although this felt a little daunting at first, the benefits for students soon became apparent. They could access the learning at a time, location, and pace appropriate to them as individuals - this really benefitted the students with other time commitments, and also those who were consistently at the bottom end of the grades, as they could take their time to learn.

Creating learning objects can be time consuming initially, but will save you time in the long run. I would recommend for anyone to take their teaching online in this way.”

By the end of this week, you should be able to:

- understand some of the essential principles of online teaching

- be aware of some key learning theories and classifications of online teaching technologies

- understand the concept of learning objects and some of the different classifications of these.

1 Principles of effective online teaching

In Week 1, we introduced some of the ways in which online learning can create new opportunities and benefits for teachers and learners. However, in order to realise those benefits, certain principles need to be followed to optimise the online experience for learners.

Activity 1 Challenging preconceptions about online teaching

Watch the video ‘What are some benefits to teaching online?’ and make a note of any concerns expressed that you had not already thought of regarding your own teaching context.

Transcript

Dr. Donald Opitz, Assistant Professor, School of New Learning, DePaul University, Chicago:

So one of my fears of starting to teach online was: would I get the same kind of thrill on teaching as I would in the classroom? I was a little sceptical that students would actually have the same-quality learning experience in an online environment as they would in the classroom, and that I, as an instructor, would have the same kind of role – and not simply a facilitator or a discussion manager.

And actually, I was really impressed by how much I benefited from teaching online, in the sense that I could see how students were developing in their thinking about the course topics. There’s a certain kind of dialogue that happens textually that you don’t get face-to-face. Even if it’s not synchronous, students spend more time reflecting upon what the course subject is and coming up with responses and the reactions, and how they’re processing the material.

And it’s really rewarding to see that happen. You do enter into relationships with students: it’s a little different because you don’t see the students, but you do have really meaningful discussions with them that are very intellectually engaging. So I was a sceptic and now I would say I’m a fan of online instruction.

Discussion

Often teachers have preconceptions about teaching online and what they or their learners may ‘lose’ if they take their teaching online.

This week’s material and activities are designed to help you to separate perceived advantages and disadvantages of teaching online from the real ones, as applied to you in your own context.

Rather than being a simple binary choice, there are lots of options and ways of tailoring online teaching to any context. So it is important to be aware of key concepts and types of tools, consider what is known about these, and to have an approach that allows you to trial ways of teaching online and to understand the results. The course will help you to develop in each of these areas.

Searching the web for ‘principles of effective online teaching’ brings up many different takes on the topic, each slightly different. On the following pages you will find a summary of some of the key principles that almost always feature in these lists. They have been gathered from a range of sources but have been inspired in particular by Cooper (2016) and Hill (2009).

1.1 Create a schedule

In the face-to-face teaching environment, the teacher is not available to learners at all times of the day and night, every day of the week. When moving to an asynchronous online learning environment it is tempting for students to expect that the teacher should be always available. As the teacher, you need to establish a set schedule of when you are, and are not, available to learners. If they will need synchronous support, drop-in tutorials can be scheduled. Otherwise agree that you will respond to messages within a specific time period so that, for example, if a learner contacts you after a certain hour in the evening, they know not to expect a response until the following morning. Similarly, provide a schedule of expectations to learners – tell them by when you consider they should have reached each milestone in the course and follow up when students miss core deadlines. This should help keep on track those learners who are less capable of motivating themselves to progress through the course.

1.2 Keep learners informed

Make sure you repeat information about core deadlines often. If there are to be synchronous learning events (such as webinars and group tutorials) make sure learners are reminded of the event several times in the weeks and days leading up to each event. If there is to be a change to planned activities, for example if you will be away and unable to respond to messages for a few days, make sure the learners are kept informed well in advance, and designate an alternate person the learners can contact if they need assistance urgently.

1.3 Foster a sense of community

Wenger’s (1998) concept of ‘communities of practice’ has gained traction in education over the past two decades. Wenger suggests that people who share a common goal or purpose can form a community of practice through which they share insights and experiences. Members of a community are practitioners in a particular area. For example, they could be teachers in a subject area who discuss their ideas and experiences in a shared online space. Active participation in a community of practice is a social process, and yet it enhances individuals’ learning and can also increase their social capital through developing connections and recognition.

Building community is important for online learning, where learners can readily drift away or feel isolated due to the nature of online engagement. So think about steps to keep them together and engaged. This might involve reminding them of what they are supposed to be working on at any given moment, or fostering a sense of community between the learners by making yourself a key part of that community. Drawing on the concept of communities of practice, you could emphasise that connecting and sharing with like-minded others can be very beneficial.

You might find that you spend less time engaging with students through lectures or traditional sessions because this material is instead presented in a form they can access independently at any time. In an online environment, the role of the teacher can become more supportive and collegiate, such that the learners understand that your primary role is to help them to succeed on the course. To this end, it can be useful to construct an individual relationship with each learner rather than always relying on mass or automated emails.

1.4 Ask for feedback

In tandem with fostering a sense of community, you need to check at regular intervals how the learners are doing, evaluate their progression through the course materials, and ensure they are being supported. Those who respond negatively, and those who do not respond at all, will need your attention to help them develop study strategies to get them back on track. Online feedback mechanisms can provide more formative feedback for tutors than traditional paper questionnaires (Donovan et al., 2006). It can also be very beneficial to your online teaching practice to engage in peer observation with fellow online teachers (Jones and Gallen, 2016).

1.5 Recognise diversity

One of the main advantages of the online environment is that students can learn in their own way, at their own pace. This is attractive to people who have other responsibilities or employment. As such, try not to curtail the freedoms that online study offers by imposing unnecessary limitations on the way students undertake their learning.

Differentiated instruction – a term used to describe ways in which learning might be tailored to the differences between individuals in a class – is important here. Online instructors can usefully tailor their instruction according to factors such as the individual’s ability or interests (Beasley and Beck, 2017). However, this might need to be considered in light of our previous discussion of the potential for online study to result in isolation, and the value of giving learners some shared structure to follow.

2 How can educational theories help you take your teaching online?

There are many theories associated with education, and it is not the role of this course to discuss them all. However, when referring to online education and its advantages to learners, four theories are often discussed and can help us to understand how to go about teaching online. These are behaviourism, cognitivism, constructivism and connectivism. The principles of effective online teaching outlined in Section 1 are informed by these theories.

We are not going to delve deeply into the four theories, but it can be useful to know the general ideas behind them when considering moving into the online teaching environment.

2.1 Behaviourism

Skinner (1968) and Thorndike (1928) were two of the main proponents of behaviourism. Their work examined how behaviour is linked to experience and reward. So in the online teaching context, teachers should be aware to ‘reward’ their learners for positive behaviour. This need not be solely via the domain of the assessed parts of the course, but also in giving encouragement and positive feedback for engaging in discussion activities or reaching certain milestones on schedule, for example.

2.2 Cognitivism

Cognitivism largely replaced behaviourism and came to prominence in the late 20th century. This theory concentrated on the organisation of knowledge, information processing and decision-making. Ausubel (1960) and Bruner (1966) were two of the main proponents of cognitivism. Bruner pursued the notion that learners should be given opportunities to discover for themselves relationships that are inherent in the learning material, a teaching technique he named ‘scaffolding’. In an online teaching environment, this could manifest itself in the teacher providing regular and focused support to each learner in the early stages of the course, but making less frequent supporting interventions as the learner begins to act successfully by themselves. Ausubel’s work in this area would suggest that it is better for the teacher to provide some materials in advance, that allow the learner to ‘organise’ their learning approach prior to them accessing the actual course materials, so that they have already developed much of the skillset they will need to successfully undertake the course.

2.3 Constructivism

Constructivism is concerned with how knowledge is constructed. The main proponents of constructivism were Piaget (1957) and Vygotsky (1986). Piaget was interested in how knowledge is constructed by the individual, and in particular, how children move through several quite different stages of development in terms of constructing knowledge. Vygotsky, however, was more concerned with how the social construction of knowledge has an important role to play in this process. With respect to online teaching, one of the important notions to take from Vygotsky’s work is the ‘zone of proximal development’. In short, this suggests that learners progress optimally if continually presented with tasks that are just beyond (i.e. proximal to) their current zone of ability or development. If learning tasks are repeatedly too simple, boredom quickly ensues and the learner can be lost from the course. If the tasks are too advanced, enthusiasm can be lost, frustration builds and again, the learner may lose interest. Vygotsky suggested that the tasks in that zone of proximal development are ones that most learners can achieve with just a little help – and of course, that is where the role of the online teacher becomes vital. Some of the ways in which a teacher can offer support and challenge are different from those used in a face-to-face teaching scenario, as this course will explain.

2.4 Connectivism

This theory takes into account the availability of a plethora of information on the web, which can be shared around the world almost instantaneously with the rise of social networking. Connectivism draws on chaos theory’s recognition of ‘everything being connected to everything else’. It also draws on networking principles, and theories of complexity and self-organisation, and is built on a notion that ‘the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing’ (Siemens, 2005).

Siemens explains that:

‘Connectivism is driven by the understanding that decisions are based on rapidly altering foundations. New information is continually being acquired. The ability to draw distinctions between important and unimportant information is vital. The ability to recognise when new information alters the landscape based on decisions made yesterday is also critical.’

Unlike the other theories presented above, connectivism is ‘a learning theory for the digital age’ (Siemens, 2005). It is also newer and less established in terms of a body of research. Whether or not you agree with its arguments, two very important questions for this course are prompted by connectivism: has the internet fundamentally changed what learning is? And does the internet change what education, and educators, should aim to achieve?

Activity 2 How do educational theories match with your teaching?

Make brief notes on the differences between behaviourism, cognitivism, constructivism and connectivism. Are there ideas that are present in your current teaching practice? How do they appear? Do these theories fit with your experiences of learning?

Discussion

As a teacher, you are probably familiar with these theories already, but it can be helpful to take a step back and look at your teaching with a critical eye. This activity should help you to identify where you draw on the theories, which, as you move through the course, should help you to decide where the theories will play a role in your online teaching.

Here you have explored some of the theories that inform the underpinning principles of effective online teaching. However, online teaching cannot take place without the application of technology, and this is what you will focus upon next.

3 Digital technologies for online teaching

This section of Week 2 gives an overview of the possible technologies available to an online teacher, and the ways in which they can support and influence teaching and learning.

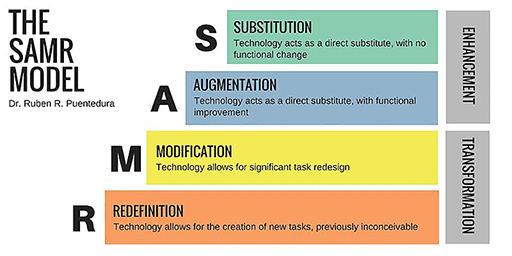

The SAMR model categorises four ways in which the introduction of technology changes teaching activity (Puentedura, 2017):

- Substitution: where technology is used as a direct substitute for what you might do already, with no functional change.

- Augmentation: where technology is a direct substitute, but there is functional improvement over what you did without the technology.

- Modification: where technology allows you to significantly redesign the task.

- Redefinition: where technology allows you to do what was previously not possible.

There has been substantial debate about the value of, and evidence for, the SAMR model (for example Love, 2015). However, it has achieved some popularity amongst researchers and practitioners. Here, we are simply using it as a way to categorise four ways in which a teacher might start to introduce technology into their online teaching. If you have time, you may wish to explore some of the discussions about the value of this model, starting by following up the references above.

The following sections describe different groups of tools that teachers might commonly use in getting started using technology in online teaching.

3.1 Course management

Online courses, and courses with any online component, are usually delivered using a host platform, commonly referred to as a Learning Management System (LMS) or Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). These systems support teachers in delivering materials to the learner, keep track of registered students, and support other tasks such as assessment and communications. Teachers based in traditional universities, colleges or schools will not normally have much input into the selection process when the institution is investing in one of these products (even ‘free’ LMS systems like Moodle require investment in terms of adapting and running the product). Usually the teacher’s role is to find out what possibilities exist for teaching online using the product, and to use the elements that seem most productive in their individual context. Often a variety of tools can be included, such as blogs and wikis, quizzes and automated assessment processes, spaces for synchronous and asynchronous learning activities, and repositories for learning objects. You will learn more about the ways in which LMS tools can be used in teaching next week.

3.2 Content creation tools

With online learning comes the potential to use a variety of media within online learning materials and to use content creation tools to package them all together into a coherent learning experience. As well as providing interesting ways to use audio and video media in teaching, there are online tools available for production of graphs and infographics, animations, storyboards, and more. The teacher’s role in respect of these kinds of tools is to browse and trial a range of software and to discover which kinds would help bring their online teaching alive with a variety of media and presentation formats. Week 3 of the course provides some guidance on this process. Once you have an idea of what you want to create, you will need to identify how the outputs you create with these content creation tools can be integrated with the course management system to create a dynamic and engaging online learning experience.

In addition, you may design your materials to enable learners to use these tools in their online work. Beetham (2007) points out that:

‘Applications can even be shared to enable collaborative representations to be built, as happens face-to-face with electronic whiteboards or blackboards, and with wikis online. Learners’ representations can of course be used for assessment but they can also be re-integrated into the learning situation for reflection and peer review, or even as learning materials for future cohorts.’

3.3 Networking and collaboration tools

Google Docs and other elements of the Google Apps suite (as well as a range of other similar tools) or Dropbox allow teachers to share materials with their learners and work on them together in real time, or asynchronously. This can enable strengthening of the teacher-learner online relationship, which is particularly valuable in the early stages of a course. In addition, a range of collaborative networking tools can be used to foster group working and a sense of community between learners on an online course. Instant messaging apps can foster backchannels (Week 1 of this course introduced backchannels). Activities using Twitter or Pinterest to search for information, or using Diigo to gather together relevant internet bookmarks, can help bring an online group together with a shared objective, as well as exposing that group to a wider community in a relevant subject area.

3.4 Enhancing tools and materials you already use

Many teachers will be familiar with creating Word documents and PowerPoint presentations. Materials in both formats can be repurposed for the online environment. They are a classic example of the ‘substitution category’ of the SAMR model (Puentedura, 2017) where teachers move online the same methods they used in the face-to-face environment. However, with a little more work, static documents featuring text and images can be turned into online exploration tools, linking to websites, animations, videos, blogs and so on to enrich the learning experience. These improved Word and PowerPoint files can then be integrated with other materials using content creation tools, or mounted within a course management system, for example.

4 Learning objects

Digital networks and tools support sharing and replication of content with little effort. Unlike a physical object such as a printed book, a digital object can be copied, shared, edited, and re-shared without any impact on the original object. Many educators have explored how we might be supported to create and use digital objects in different ways to those physical objects. Over time, this has led to the development of several concepts which we start to introduce here, and return to in more depth in later stages of the course.

The concept of a learning object suggests that small, self-contained digital units of learning can be created that can then be combined, reused or adapted for repeat usage. When these started to emerge, the term Reusable Learning Objects (RLOs) was used to describe them. This was because it was argued that when a learning object was shared, it should be created in such a way that it helps another educator or learner to make use of it themselves.

Recently, you are more likely to see the term Open Educational Resources (OERs) used to describe content that is shared by educators. OER has become a more popular and widely understood concept amongst educators across the world than RLO. OER is in part an evolution of the idea of a RLO, however, the two terms are not completely interchangeable. Firstly, RLOs are, by definition, designed to be shareable, whereas OERs may be teaching materials that have been deemed shareable by the author but which have not followed a specific approach that supports other educators to reuse them. What OERs do provide, by definition, is a licence that makes it clear that there is legal provision for reuse by others according to certain rules. RLOs do not necessarily have these licenses, although to be truly reusable, they should.

Learning objects can vary in nature from multimedia packages with audio and/or video elements, to single tasks presented in text or slideshow documents, with myriad variations and varieties in between. The role of the online teacher may be to create or feed into the creation of learning objects, or it may be to use learning objects produced by other teams within the institution to deliver an online learning experience, by means of asynchronous and synchronous activities. Repositories of RLOs exist on the internet, meaning that adventurous learners may discover them and use them to enhance their learning outside of the given course materials. Examples of these repositories include Wisc-Online, and MERLOT, whose RLO contents are also OERs.

Activity 3 Learning objects and your own teaching

Watch this video ‘Learning Objects’, or read the transcript and then identify and note down three potential learning objects that could be created from the materials that you have used in your own teaching or learning. Consider whether these might be successfully reused by others online, and what additions or modification, if any, they would need to be useful learning objects.

Transcript

A Learning Object is a resource, usually digital and web-based, designed to support learning.

In learning objects, educational content is broken down into small chunks that can be used and reused in various learning environments.

In order for a chunk of content to be a learning object, it must be instructional and it must have intended learning outcomes.

On the screen, here, we have a recipe for Garlic, Spinach and Chickpea Soup. Let’s break it down to its component parts.

If we first consider the list of the basic food items for this recipe we would not have a learning object.

Even when we take this basic food and spice items and add quantities for each item, we still don’t have a learning object.

It’s only when we add directions that our list becomes a recipe and it also becomes a learning object.

It may not be a high quality learning object but we now have a possible learning objective which is to create this Garlic, Spinach and Chickpea Soup.

It’s not a curriculum or even a unit of learning.

It’s a chunk of educational content that can be used and reused in various learning environments.

One teacher might use it in a lesson on cooking.

Another might include this little chunk in their teaching of measurement, while a third teacher might use it to teach about nutrition or healthy eating.

And a language teacher might use it to teach reading and/or writing skills.

The term learning object is not a brand-new term, but it’s use is growing because in the past few years learning objects have been associated with on-line or web-based instruction.

As more and more people get on the internet with higher and higher bandwidth it becomes possible to create educational content that uses different kinds of media.

Until recently TEXT was the type of media most often used in learning.

Now graphics can be used along with text, and video, audio and animation can be added to provide a very rich learning experience for the students – one that can better accommodate learners with different learning styles.

Learners can not only read but also observe and listen.

The final ingredient – interactivity – is very powerful because it allows learners to do quizzes, choose learning paths, be evaluated or even interact online with other students or their instructors.

They can make decisions, problem solve, work at their own pace and apply what they’ve learned.

Imagine the possibilities for learning objects in the future.

Discussion

This activity should help you to start thinking about resources you already use, and how they might work in online teaching. If you completed this exercise quickly, you might find it helpful to go on to perform a brief audit of all of the learning objects that you currently use, so that you could consider repurposing any or all of them in your future online teaching.

Churchill (2007) proposed a typology that may be useful when thinking about the variety of learning objects and their purposes:

- Presentation object: Direct instruction resources to transmit specific subject matter.

- Practice object: Repeat practice with feedback, educational game or representation that allows practice and learning of procedures.

- Simulation object: Representation of some real life system or process.

- Conceptual model: Representation of a key concept or related concepts of subject matter.

- Information object: Display of information organised and displayed with modalities.

- Contextual representation: Data displayed as it emerges from represented authentic scenario.

Now is a good time for you to develop your own plans for taking your teaching online. Each week you will build further upon these notes until you have a comprehensive plan of action.

Activity 4 Building learning objects into your plans for teaching online

- Last week in Activity 4 you were asked what teaching you might want to deliver online, who you would deliver it to, and what materials you might repurpose. Revisit your notes about what you want to deliver online. If you typed your notes into the box in Week 1, they will automatically appear below this list.

- Now return to this week’s learning. Which types of learning object might you develop or reuse in order to deliver the objectives you have?

- Next, revisiting Section 1 of this week, consider how you might build or integrate your learning objects in a way that takes into account the ‘principles of effective online teaching’.

- Finally, consider which tools you might need in order to create an effective learning experience using these objects. At the moment, you might not know the names of all the relevant tools, and that’s fine – simply write something like ‘a tool that will allow me to…’ and continue the sentence with a specific action such as ‘combine video with passages of text’ or ‘give my learners a multiple choice quiz’.

As with Activity 4 from Week 1, save your responses as a Word document on computer or in your reflective journal, as you will build upon them later in the course.

Discussion

Here you are building on your responses from last week, to move your plan for online teaching another step forward. It is important that you consider not only the learning objects you may wish to reuse, but also how you might use them, both pedagogically (part 3 of the activity) and in terms of how the technology might help you to deliver them (part 4).

5 This week’s quiz

Check what you’ve learned this week by taking the end-of-week quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’re done.

Summary

In this week you have looked at the core theories and principles that underpin good quality online teaching. You have also started to look at the digital technologies involved in online teaching and the use of learning objects – both of these will be revisited in much more detail later in the course. In fact, next week’s material is all about the technologies that you can use to deliver your online teaching.

Finally for this week, let’s see how Rita’s getting along.

Transcript

NEW Text-based alternative to Rita video.

Rita is now starting to fit some pieces of her online learning puzzle together. She can see how her existing knowledge of education theories fits with what she hopes to achieve online.

Rita’s university already has a Learning Management System, so she can prepare to use that to host the teaching materials she will use to support her online lessons. She will reuse the PowerPoints she already uses in the classroom, and she will still point her students to key resources on the internet, but she is aware that she will need to change some of the structure of the materials if she is going to use the ‘flipped’ approach. Some of the tasks that students currently do after class, they would do before class in the online course, and so a little extra guidance might be necessary.

Rita is starting to conceptualise some of her lessons as ‘learning objects’ that students can interact with away from her presence (either in the classroom or online). She is realising that if she can create some learning materials that ‘stand alone’ online, she can spend more of her time answering students’ questions and helping those that are struggling to understand. Her synchronous lessons will then become more like ‘workshops’ helping students to understand the subjects, rather than ‘teaching’ them in the traditional way (the ‘teaching’ would be partially achieved by the learning objects that the students access before the online classes).

Now that Rita has some very specific ideas for what she wants to achieve, she must discover which technologies she might be able to use to make this happen. And that is what we shall examine next.

You can now go to Week 3.