Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Friday, 13 February 2026, 5:40 AM

Week 4: Supporting learners with different needs – accessibility in online teaching

Introduction

It is important to ensure that your learning materials are suitable for as wide a range of learners as possible, whether they are materials you create yourself, or resources that you find online and reuse. Accessibility, usability, inclusion and universal design are all commonly used terms for ensuring that your learning materials can be used by a wide range of potential learners, including those with disabilities who may be using assistive technologies. For the purposes of this week’s materials, we use ‘accessibility’ as a shorthand. Note that this is not necessarily advocating a one-size-fits-all approach to every learning object, and that it can be perfectly appropriate to provide alternative materials or activities for some situations, as long as the overall learning objectives are met for all learners. However, effort and understanding applied to this area can save a greater amount of effort and difficulties later on, and make the learning experience better for everyone.

To understand some key themes in accessibility, you will first learn about assistive technologies and the impact they have upon the way learners interact with learning materials. You will then learn how to make the materials you use more accessible, and finally some guidance on alternative formats.

Teacher reflections

We join Dr. Nilar this week for her experiences of considering accessibility. She focuses on ways of working with PowerPoint to make use of its full potential for inclusive teaching:

“Hello there! I’m a zoology lecturer teaching mostly final year undergraduates and Masters students. My name is Dr Nilar. While my priority is always to teach zoology as effectively as I can, I have developed a strong interest over the years in being as inclusive and accessible as possible in my teaching.

One of the first and easiest ways that I started making accessibility part of my everyday practice as to consider alternative formats. Am I presenting information in a way that some of my students are going to find difficult to absorb, because they have a visual impairment , for example? From time to time I use PowerPoint to present information in my teaching like most of my colleagues. One thing I always do with my slides is ensuring the colour contrast between text and background is optimised for accessibility (I usually use navy text on a pale yellow background and I have my default setting in PowerPoint set to produce that). I also ensure that if my PowerPoints will be put online, Google Drive, for example, for students to download, I make sure I add alternative text (alt text) to any images or graphics. This is very easy to do in PowerPoint. It also helps students who want to listen to the PowerPoint being read out automatically offline (so they can listen on their phone, for example). I don’t have to narrate it - there is free software that reads it aloud, but obviously images cannot be read, so you must provide the alternative text to enable the students who are listening to get a sense of what the images show.”

By the end of this week, you should be able to:

- define assistive technology and list a variety of examples

- understand how to make most of your online teaching materials accessible

- assess the accessibility of OERs

- understand what alternative formats may be needed in online teaching.

1 What is assistive technology?

The term ‘assistive technology’ is used in this course to refer to any technology that:

- makes it possible for a disabled person to use a computer

- makes their use of that computer more efficient

- enables them to access online information such as online learning materials.

Assistive technology, or enabling technology, can also be used in a wider sense to refer to any technology used by disabled people to enable them to carry out a task. For example, a definition from Doyle and Robson (2002) describes it as ‘equipment and software that are used to maintain or improve the functional capabilities of a person with a disability’ (p. 44).

Assistive technologies can facilitate access to teaching material by bridging the ‘access gap’ between the teaching material and the learner. The materials may not have to be altered if it has been designed appropriately, and if the learner can access them using suitable assistive technologies. There is often a learning curve associated with becoming skilled in their usage, and this should always be borne in mind. Whilst assistive technologies may make the difference between a learner having access to learning materials or having none, they may not completely remove all barriers or provide the same experience that other learners are getting.

For learners to interact with online learning materials, the kinds of assistive technology they may need to use include technology that facilitates:

- access to a computer and the internet

- access to and manipulation of text

- access to and manipulation of sounds and images.

Assistive technology includes hardware such as scanners, adapted keyboards or hearing aids, and software such as text-to-speech or thought organisation software. Assistive technology is often associated with high-tech systems such as speech recognition software, but it can include low-tech solutions such as arm rests or wrist guards (adapted from Banes and Seale, 2002).

1.1 Types of assistive technology

There are many types of assistive technology. Some common tools that you may encounter include:

- Display enhancement tools. These might be used to adjust colour combinations on screen, or to magnify text or particular areas of the screen, or to make the mouse cursor more obvious, amongst other things.

- Audio tools. These might be used by learners to read text from the screen aloud (also known as text-to-speech), to translate or define key words, or to record contributions or feedback. It is important to note the distinction between text-to-speech tools, which require the learner to select the text to be read and are commonly used by people with dyslexia or a degree of vision impairment, and the much more complex screen readers.

- Screen readers. These tools read everything presented on screen, as well as navigation options and menus, and are used by people who are blind or severely vision impaired to operate their computer, as well as to read on-screen text. They can take a long time to learn to use, but when a user is expert they can often listen to items being read out at a much greater speed than regular speech.

- Writing tools. These may help learners with spelling or sentence construction, or may help students who cannot use a keyboard to enter text by other means. On-screen keyboards can help learners to enter text by using a switch or pressing the space bar, alternative entry tools can help learners to enter text by nudging a mouse or even using their tongue to open or close an airpipe, and speech recognition tools can help learners to enter text by speech.

- Planning tools. These can include tools that create thought maps (and convert these to nested lists, or vice versa), as well as tools for annotating the screen, as reminders or planning aids.

Assistive technologies are not always separate items to be purchased by the user. Often mainstream technologies have assistive technology features built in. Operating systems such as Microsoft Windows and Apple Mac OS contain built-in assistive technologies, such as display enhancement tools and audio tools. Word processing software often includes tools such as magnification controls, navigation via headings, or readability checkers, and modern internet browsers also contain a range of assistive features. Because these are readily available, you can try some of these tools yourself to get a sense of how they work.

Activity 1 Discovering assistive technology built into internet browsers

Watch the video on Accessibility and web browsers to see an overview of browser-based assistive aids. Make a note of any that you were previously unaware of.

Discussion

Whilst it is not necessary for every teacher to become an expert in assistive aids, it is a valuable exercise to familiarise yourself with the range of tools available, particularly those available at no cost in browsers and operating systems. This activity helps to highlight some features that you may not have been aware of.

It is important to be aware of the kinds of assistive technologies learners may have available to help them to access online education. However, this is only one part of the story. In order to minimise barriers to disabled learners, you must also deliver learning materials that are accessible. Often, assistive technologies will only function optimally if learning materials have been designed with accessibility in mind. This is what we will consider in the next section.

2 Making your online materials accessible

There are many types of disability, and many ways in which people with disabilities interact with learning materials. Therefore, generalising about all the considerations that need to be made for learners with particular impairments or conditions is tricky. However, there are common aspects of achieving accessibility in learning materials. You should ensure that:

- materials are clear, consistently organised and explanatory

- information contained in visual elements (e.g. images, video, and text) can be accessed without needing vision

- information contained in auditory elements (e.g. video or sound clips) can be accessed without needing hearing

- display elements can be modified to suit the users needs (e.g. magnification, colour contrast)

- tasks can be performed without needing rapid text input skills, manual dexterity, or visual acuity.

Meeting these requirements does not mean that you have to avoid using elements that some people cannot access (such as video, for example), but rather that you should ensure that the information that you are conveying can be accessed by everyone, albeit in different ways or through different media.

2.1 Ensuring clarity of navigation and appearance

Colour

Do not use colour alone to convey meaning. For example, if a completed task in your course has a green dot beside it, and uncompleted tasks have red dots, that is going to be problematic for a colour-blind learner. Changing this to a green tick and a red cross may resolve this issue.

Headings and structure

Structure headings using style features built into the tools you use. These exist in Learning Management Systems, Word, PowerPoint, and other common tools for creating content. Using heading styles when creating text documents enables screen reader users and dyslexic learners to navigate the document more easily.

Presentation slides

Using the built-in slide designs in PowerPoint ensures that all text content is accessible to screen readers. Text that is displayed in the ‘Outline View’ of the presentation is normally accessible to screen readers, but text added via additional text boxes is generally not accessible. Hence it is good practice to copy all text from each slide into the Notes field (which can be accessed by screen readers) and to add into the Notes field descriptions of any visual elements of the slide as well. PowerPoint slides read by a screen reader are read in the order the content was added to a slide, which sometimes is not the proper reading order. The reading order can be changed in PowerPoint to fix this issue.

Text alignment

Where possible, ensure text is left-aligned (meaning the right edge is uneven) rather than justified (where both left and right edges are uniform). If text is left-aligned, the letter and word spacing is optimal for readability. However, if text is justified, uneven spacing between letters and words can significantly reduce readability, especially for some people with dyslexia, who can find they ‘slip’ up and down in the ‘rivers of white space’ that appear in justified text.

PDFs

Avoid using PDFs in which the text is saved as an image – this cannot be read by screen reading software. You can test whether the text is saved as an image by trying to select a few words with the cursor – if words are not individually selectable, then the text is probably an image. Screen reading software therefore cannot detect any words, and therefore will not read the PDF contents. Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software can be used to attempt to extract text from an image, but the process is rarely completely accurate and so you need to examine the output of the OCR software and correct any errors. PDFs generated from accessibly structured Word or PowerPoint documents (see ‘Headings and structure’ and ‘Presentation slides’ above) are usually also fairly accessible (Devine et al., 2011). The University of Washington has produced some useful guidance on creating accessible documents in Microsoft Word and creating accessible PDFs from Word documents.

Layout and organisation

Use clear, consistent layouts and organisation schemes for presenting content. Initially post regular announcements on how to get started, and orient students to the course. Direct students to key areas – contents/overview sections, schedules/timetables, assessment guidance. Organise your course in a linear fashion so a student knows that if they navigate from the first page in the course content to the last, they will have covered all of the required course materials, assignments and assessments.

In text documents (Word, PDF, etc.) content needs to be laid out in a very linear fashion to be accessible, so don't use textboxes (in MS Word, Insert > Textbox) or tables to lay out a document. Tables should only be used for tabular data.

Tables

If tables do not have an approximately equal number of rows and columns, they should be oriented ‘tall and thin’ and not ‘short and wide’. This is because screen readers read a table linearly, row by row.

If your table has more than two columns and more than ten rows, it’s good practice to repeat the column headers every 10–12 rows, just to remind the screen reader user what they are listening to.

To see a few more examples and guidelines, have a look at this page produced by WebAIM, which gives some more information about ‘accessible table design’ for web pages.

Web links

Use descriptive wording for link text to make each link distinct and the destination clear. So avoid the meaningless ‘Click here’, or having several links called ‘Read more’. This is because many screen reader tools offer the user an option to quickly scan all of the links on a page, so that the user can rapidly navigate through to the page they seek – however, this functionality becomes useless if all the links have generic names or if there are several with the same name.

2.2 Making visual elements accessible

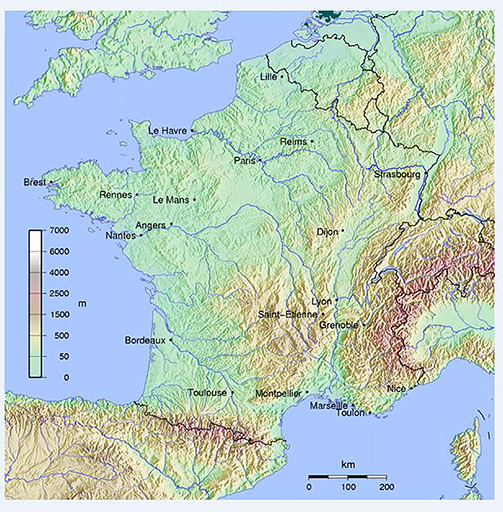

Provide concise alternative text descriptions of content presented within images. This should focus upon the purpose of the image in relation to the teaching points, rather than a description of every visual feature. The alternative text could therefore be different for the same image used in two different ways. For example, Figure 5 below shows the locations of principal cities and rivers of France. It might carry two quite different alternative text descriptions depending on the purpose of its usage:

- (in a lesson on rivers) A map of France, showing that the catchments of four large rivers (the Seine, Loire, Garonne and Rhône) drain more than three quarters of France’s mainland. The Seine drains largely north-westward into the English Channel, the Rhône southward into the Mediterranean, and the Loire and Garonne largely westward into the Atlantic Ocean. The Garonne’s headwaters are to be found in the foothills of the Pyrenées, the Rhône has its source in the Alps, the Loire originates in the Massif Centrale and the Seine rises in the Langres plateau in the north-east of the country.

- (in a lesson on settlements) A map of France, showing that five of France’s twenty largest cities by population are seaports. Le Havre, Brest, Marseille, Toulon and Nice are all seaport cities, while Paris and Bordeaux are principal inland ports. All the rest of the twenty largest cities are situated on or near rivers, but are not considered major port cities.

Note that the first description makes no mention of the cities shown, whilst the second makes no mention of specific rivers. When creating alternative text it is important to focus only on the information the learners need to know about the image, and to not clutter your description with unnecessary information. By doing this, the alternative text also becomes a valuable learning aid for all learners, as you are distilling for them the key elements of the image.

It is not always necessary to add alt text for an image – if the image is purely decorative and serves no educational purpose, you do not need to add alt text. However, if you are creating a web page you must still give it a ‘null alt tag’ (alt=””) to ensure screen readers know they should skip it, otherwise they will say ‘image’ and the learner will be left wondering what it was.

It is also necessary to make the content of video or animations accessible for those who cannot see it. Usually this is done by the provision of a transcript. Depending on the nature of the video content, it may be appropriate for the transcript to simply replicate any spoken words in the video (dialogue, commentary and so on). However, sometimes it will also be necessary to add descriptive detail of a similar nature to the alternative text for images. This is especially vital when the spoken element does not cover key visual information (for example if someone is demonstrating a technique and does not describe every step they make because they believe the audience can see what they are doing).

Ensure that the playback of visual elements can be controlled by the user – you can imagine how difficult it is to listen to your screen reader interpreting what is on a web page at the same time as a video begins automatically playing and you cannot stop it.

Activity 2 Describing images for those who cannot see them

Please note that, because of the intended learning outcome, this activity itself is inaccessible to screen reader users. However, we expect that they are already familiar with the concept of alt text which is explored here.

- The image shows a section of a typical city centre street in Kandy, Sri Lanka.. Draft some alternative text that might be suitable for the following uses of the image:

- In a discussion of the modes of transport commonly used in Kandy.

- In a discussion of the kinds of businesses one may find together on a typical Kandy street.

- In a discussion of the state of repair of buildings on a typical Kandy street.

Discussion

Your alternative text should contain similar elements to these:

- i.This is a photograph of a typical city centre street in Kandy. Vehicles are parked outside a variety of shops along the street. Visible are two motorcycles, one small car, one multi-passenger vehicle and four brightly coloured tuk-tuks. This may be an indication that small vehicles that can weave in and out of traffic are popular in Kandy.

- ii.This is a photograph of a typical city centre street in Kandy. Buildings are packed together with no spaces in between, each only one room wide. A shop selling glass for pictures, doors and windows sits next to a shop selling leather and floor coverings. Beside this is a shop with a brightly-coloured array of children’s toys and balls hanging above the window and doorway. Next to this is a retailer of window blinds, with the neighbouring shop specialising in motorcycle parts. Finally, at the edge of the photograph is a jewellery shop.

- iii.This is a photograph of a typical city centre street in Kandy. Buildings are packed together with no spaces in between, each only one room wide, and two or three storeys high. Whilst the street-level shop fronts are mostly in a good state of repair, the upper levels of many of the buildings are shabbier and in need of repair. Rainwater goods are commonly dilapidated, and missing in places, and the tiled roofs that are visible are uneven and have been patched with corrugated fibreboard. Where window frames and shutters are wooden, these are starting to warp and fit poorly. The building on the right edge of the picture appears to be covered with scaffolding and blue netting.

It is evident that the alternative text can be written in many different ways, so as to deliver to the learner only the details relevant to the context of its use. Describing all of the possible details to all of the learners could waste their time and create for them a difficult task of trying to separate the relevant details from the irrelevant ones.

2.3 Making auditory elements accessible

There are two common ways to make audio elements accessible to those who cannot or who do not wish to listen to them. With videos, the most common technique is to add subtitles or closed captions.

In some cases it may be more appropriate to provide a separate text transcript. This can work very well for audio, or for some videos such as interviews where the visual element isn’t essential to understanding the content. If the video content is more complex, remember that it may be difficult to read a transcript and watch a video at the same time.

In either a transcript or subtitles, it can be important to describe any meaningful sounds, not only the spoken words.

Be aware that if you use an automatic captioning tool, such as the one provided by YouTube, you must check and edit the captions it has provided to ensure accuracy. The output created by these tools is often inaccurate but can be improved manually.

2.4 Making display elements adjustable

Learners may view your content through a range of different devices, screens and browsers. However, there are some common features that you can control that help to make sure the materials display in a form that is accessible to a wide audience. The first is to use as default an accessible combination of settings. So it is good practice to use a font type that has good readability (sans serif fonts are often recommended for printed materials, but online some serif fonts can be suitable if they are not cursive or uneven) and a font size of at least 12 point in text documents (and 20 point on presentation slides). Colour combinations should give good contrast (there is a free colour contrast checker which helps you assess the contrast of colour combinations – you should aim for a minimum ratio of 4.5 to 1 throughout – and for large amounts of text you should aim for a contrast ratio of 7 to 1).

Avoid using flashing or moving elements unless there is a means for users to stop the movement. Also, avoid putting text over background images – this decreases readability dramatically.

The second element of ensuring the accessibility of the display of your materials is to put control into the hands of the learner. If you provide documents created accessibly, the learner will be able to apply their own preference of font, colour and so on. If you are presenting materials to be viewed in a web browser, provide links to guidance on how to use your browser to meet some of your accessibility needs and preferences (such as these resources for Firefox, Internet Explorer, Chrome, and Safari). If you are using another kind of platform to deliver your online teaching (web conferencing, LMS, etc.), try to find out what accessibility features it has, and give guidance to your learners on how to find and use them.

2.5 Ensuring tasks can be completed without needing manual dexterity or visual acuity

Many people use assistive technology that replicates the functions of a keyboard rather than a mouse. Others cannot use a mouse accurately. Therefore, you should make sure that all content and navigation is accessible using the keyboard alone. This means that if you wish to use elements that require manual dexterity (such as drag-and-drop exercises or crossword puzzles) or visual acuity (such as wordsearch games or ‘spot the difference’ images), then it should be possible to complete these using the keyboard alone, and the mouse alone (perhaps in combination with the on-screen keyboard built into most operating systems), or you should provide alternative activities for those who may not be able to undertake the original tasks. To test this, move your mouse out of reach, and try performing the activity using the Tab, Space, Arrow and Enter keys. If it can be achieved, add instructions for your learners advising how to do it. If it cannot be achieved, think about how to provide an alternative activity. Similarly, trial your resource using the mouse alone.

3 Checking the accessibility of materials

When you are creating the learning materials that you will use online, it is a relatively simple process to ensure they are as accessible as possible (see Section 2 of this week’s materials). However, you also need to be able to assess, and if necessary adjust, the accessibility of other people’s materials that you want to reuse in your own teaching. Whilst there are automated tools available that give some indication of a resource’s accessibility (such as MS Office’s Accessibility Checker feature, PowerPoint’s Accessibility Checker feature) or web page accessibility checking tools (such as AChecker or WAVE), you must always apply your own judgement and common sense to the outputs of these tools, and use them as just a part of a more holistic assessment of the resources.

There are surprisingly few guidelines available covering how to evaluate OERs for accessibility, but you might find it useful to take a look at this document ‘Rubrics for Evaluating Open Education Resource Objects’ (Achieve, 2011) which contains a variety of guidance, with Rubric VIII (pages 10 and 11 of the document) giving some useful suggestions as to what to look out for. However, this document is very USA-centric, with references to legislation and organisations that may not be applicable if you are based elsewhere in the world.

OpenWashington (2017) suggest six key accessibility questions to ask when considering reusing learning materials:

- Is all written content presented as text, so students using assistive technologies can read it?

- If the materials include images, is the important information from the images adequately communicated with accompanying alt text?

- If the materials include audio or video content, is it captioned or transcribed?

- If the materials have a clear visual structure including headings, sub-headings, lists, and tables, is this structure properly coded so it’s accessible to blind students using screen readers?

- If the materials include buttons, controls, drag-and-drop, or other interactive features that are operable with a mouse, can they also be operated with keyboard alone for students who are physically unable to use a mouse?

- Do the materials avoid communicating information using colour alone (e.g. the red line means X, the green line means Y)?

It is usually fairly straightforward to adjust features like font size or colour combinations in OERs, and to add or amend alternative text for images. If you wish to use a video that does not have captions (or is not in your language), you have several options:

- For YouTube videos, contribute captions of your own: look on this YouTube Help page for advice (remember the advice in Section 2.3 regarding the quality of automated captions).

- For TED talks, contact the community of voluntary caption providers.

Use a free software tool (such as Amara or Dotsub) to create your own captions.

4 Alternative formats

As you have already seen in this week, some students might have difficulties with any type of media used in online learning materials. If content can be provided in a variety of alternative formats, students will not have to do their own work to transform this into something suitable for themselves before they can engage with their learning.

For printed materials or inaccessible text formats, some work may be needed to create an alternative resource. This might be, for example, if the text is actually an image such as a photograph or scan – to check this, try ‘highlighting’ or ‘selecting’ the text. If it is not possible, the text is probably an image. It may be possible to use Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software to automatically turn text in an image into a more usable format. Always check the results of any OCR conversion for accuracy. In some cases where the text is not clear (such as with handwriting), it can be more efficient to type in the text rather than use OCR. Headings and other useful styles may also need to be added manually.

If there are images or diagrams in the original resource, someone with some understanding of the subject can determine which of these need describing and can provide the descriptions. In the case of complex images, it may be necessary to produce a tactile diagram for blind students. Tactile diagrams require technical skills and some specialist knowledge. See the video ‘How to make a tactile diagram’ (Art Beyond Sight, 2009), which provides an overview of the requirements and production of this alternative format.

In some subjects, such as mathematics, music and chemistry, there are substantial difficulties in providing an accessible format that includes the symbolic notation. Most of the guidelines for accessibility skip over this, or assume that the amount of notation is small and can be dealt with by supplying descriptions. In fact, communicating these kinds of complex notations to people without vision is a highly specialised area and beyond the scope of this course.

Some online materials are offered in e-book formats such as EPUB and MOBI (for Kindle). These formats are not aimed specifically at disabled learners, but have included accessibility considerations where appropriate, so may be beneficial to some disabled students who choose to use e-book readers.

Human voice recordings of text are often preferred by learners to the kind of computer-generated speech produced by screen reader software. Computer-generated voices may also have difficulty in reading out complex notations correctly. This includes subjects such as mathematics, music and chemistry, as well as those with a high number of technical terms. Recordings may be delivered in a variety of formats but MP3 is likely to be the most satisfactory to obtain a balance of sound quality with a manageable file size. If you do not have time to make the recordings yourself, or if you do not wish to do so, there are tools available that will convert a text document into a computerised spoken-word audio file. The free web resource Robobraille will permit you to upload a text document and have it converted into a computerised voice recording, or an e-book. (At present this service does not offer any of the main Myanmar languages unfortunately).

For audio, a transcript is the standard alternative format, and these can be beneficial to all learners, not only those who are deaf or hard of hearing. It is, however, very difficult to follow a visual medium like video and attend to a transcript at the same time. It is not the same task for a deaf person as it is for a hearing person who can at least listen and read at the same time. Students often need to make notes while watching a video, which increases the difficulty. So be aware that this alternative may not provide equity of experience for the learners.

Activity 3 Accessibility in your online teaching

You have already made notes in previous activities on what you want to achieve in online teaching. Now consider accessibility – what will you need to do with your existing materials (or reused OERs if you choose to use them), in order to deliver optimally accessible teaching online?

Make a list of six initial steps you could take fairly easily (for example ‘review my PowerPoints for added text boxes and explanation of images’, or ‘check colour contrast in reused OERs’).

Again, keep your answers in a safe place, as you will revisit them.

Discussion

This activity is designed to help you to think about the needs of your audience, and how your learning objects or online teaching materials might work for them. Accessibility should not be viewed as an additional burden for the teacher, but as an element of quality control, ensuring your online teaching is fit for purpose, by not excluding learners with particular impairments.

5 This week's quiz

Check what you’ve learned this week by taking the end-of-week quiz.

Open the quiz in a new window or tab then come back here when you’re done.

Summary

This week you have learned about assistive technologies and how users with impairments interact with online teaching materials. You have learned how to make your online materials more accessible, how to produce alternative versions where necessary, and how to consider accessibility requirements when searching for Open Educational Resources.

Rita certainly has something to say about this week’s materials – let’s see how she’s getting on:

[This animation featured in Week 6 of the original version of this course on OpenLearn.]

Transcript

Rita says that she was quite apprehensive about this topic. She was already aware that there are a lot of different types of students that could be present in her classroom, and that she would need to adapt her teaching to meet their needs - she is confident that she could help any student who appeared in her classroom. But she wasn’t sure how to make her online materials accessible as in an asynchronous environment she may not be around to help them.

After this week’s material she feels more confident. She has a list of easy things to do when putting materials online to make them more accessible. She plans to make it a regular habit to write alt text for images in her powerpoints, to provide transcripts or captions for videos, and alternative formats for materials that might be inaccessible.

She plans to try to speak more clearly and carefully in her online teaching, to benefit those students who speak different languages or dialects, or who have hearing difficulties.

Rita also plans to contact the disability support staff at the Myanmar Federation of Persons with Disablities or the Myanmar National Association of the Blind

to find out if they have any guidance for how to create accessible online teaching materials. Perhaps they could even review and give feedback on her first attempts. After this week’s study she feels confident enough to produce materials that she thinks should be at least moderately accessible, and then perhaps the disability specialists could help her to improve even further.

Continue to Conclusion to finish your study.