Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 22 November 2025, 6:30 AM

Unit 1: What is copyright?

Introduction

What is copyright and why is it important?

Copyright is an area of law that regulates the way the products of human creativity are used – like books, academic research articles, music and art. Copyright grants a set of exclusive rights to a creator, so that the creator has the ability to prevent others from copying and adapting their work for a limited time. In other words, copyright law strictly regulates who is allowed to copy and share with whom.

Copyright law is an important area of law that affects many aspects of our lives, whether we are aware of it or not. Activities that are not regulated by copyright (such as reading a physical book) become regulated by copyright if technology is used to share the same book on the internet, for example. Because almost everything we do online involves making a copy, copyright is a regular feature in our lives.

The internet has given us the opportunity to access, share and collaborate on human creations – all governed by copyright – at an unprecedented scale. However, the sharing capabilities made possible by digital technology are in tension with the sharing restrictions embedded within copyright laws around the world.

You are probably aware that Myanmar has a new copyright law that was adopted in May 2019. This unit:

- provides background on the new Copyright Act

- explores Myanmar copyright law in relation to other regional and international copyright laws

- explores the new Copyright Act’s implication for higher education.

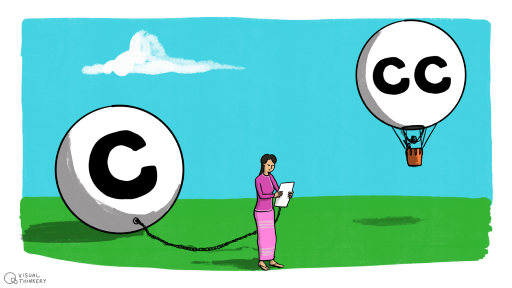

In Unit 2 we will discuss works that are no longer subject to copyright – these are called resources in the public domain – and will also introduce Creative Commons. Creative Commons was created to help address the tension between a creator’s ability to share digital works globally and copyright regulation. The default of ‘all rights reserved’ copyright is that all rights to copy and adapt a work are reserved by the author or creator (with some important exceptions that you will learn about shortly). Creative Commons licences work with copyright and enable a ‘some rights reserved’ approach, enabling an author or creator to free up their works for reuse by the public under certain conditions.

To understand how Creative Commons licences work, it is important that you have a basic understanding of copyright.

This unit has four sections:

- 1.1 Copyright basics

- 1.2 Myanmar copyright law

- 1.3 Global aspects of copyright

- 1.4 Exceptions and limitations of copyright

There are also additional resources if you are interested in learning more about copyright topics covered in or excluded from this unit.

This unit is important because Creative Commons licences and public domain tools depend on copyright in order to work. The intention of Unit 1 is to provide an overview of the basic concepts that are most important to understanding how Creative Commons licences operate. While some aspects of copyright law are harmonised around the world, the laws of copyright vary –sometimes dramatically – from country to country.

The information contained in this unit is not intended to be exhaustive or to cover all aspects of the complex laws of copyright around the world, or even every aspect of copyright that may impact how the licences operate in a particular situation. The description of Myanmar copyright law is for information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

1.1 Copyright basics

Is copyright confusing to you? Get some clarity by understanding its history and purpose.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- trace the basic history of copyright

- explain the purpose of copyright

- explain how copyright is automatic

- explain general copyright terms

Reflection

Myanmar copyright law is changing. These changes will have an impact on the way you work and your everyday life. Many copyrighted resources are being shared or used without permission. How do you find and share resources? Do you think about copyright or about who created the material you share?

Overview

Copyright law limits how people can use the original works of authors – or creators, as we often call them. Original works can be anything from novels and lyrics to cat videos and scribbles on a napkin.

Although copyright laws vary from country to country, there are certain commonalities among them globally. This is largely due to international treaties, which are explained in detail in Section 1.3.

There are some important fundamentals that you need to be aware of regarding what is copyrightable, as well as who controls the rights and can grant permission to reuse a copyrighted work.

Copyright grants a set of exclusive rights to creators or rights holders, which means that no one else can copy, distribute, perform, adapt or otherwise use the work in violation of those exclusive rights. This gives creators or rights holders the means to control the use of their works by others, thereby giving them an incentive to create new works in the first place. The person who controls the rights, however, may not always be the author. It is important to understand who controls the exclusive rights granted by copyright in order to understand who has authority to grant permissions to others to reuse the work:

- Work created in the course of your employment may be subject to differing degrees of employer ownership based on your jurisdiction. Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States adhere to some form of a doctrine commonly known as ‘work-for-hire’. This doctrine generally provides that if you have created a copyrightable work within the scope of your employment, the employer is the owner of, and controls, the economic rights in the copyrighted work – even though you are the author and may retain your moral rights. (We will find out more about moral rights in Section 1.2.) This also applies in Myanmar under the new Copyright Act of 2019, unless otherwise agreed between the employee and employer.

- Teachers, learners or a university faculty may or may not own and control copyright in the works that they create in those capacities. That depends on certain laws (such as work-for-hire in some instances) and on the terms of the employment or contractor agreement, university or school policies, and terms of enrolment at the particular institution – even though they are the creators and may have moral rights.

- If you have co-created an original work that is subject to copyright, you may be a joint owner, not an exclusive owner, of the rights granted by copyright law. Joint ownership generally allows all owners to exercise the exclusive rights granted by law, but requires the owners to be accountable to one another for certain uses they make of their joint work.

- Publishers may own and control the copyright of work created anonymously or by individuals using pseudonyms – unless the author reveals their identity.

Ownership and control of rights afforded by copyright laws are complicated. For more information, please see the additional resources section.

- Copyright does not protect facts or ideas, only the expression of those facts or ideas. That may sound simple, but unfortunately it is not. The difference between an idea and the expression of that idea can be tricky, but it’s also extremely important to understand. While copyright law gives creators control over the expression of an idea, it does not allow the copyright holder to own or exclusively control the idea itself. For a deeper look at this issue, see the additional resources section.

- As a general rule, copyright is automatic the moment a work is fixed in a tangible medium. For example, in most countries you have a copyright as soon as you write the first line of a poem or record a song. In many countries registering your copyright with a local copyright authority allows you to officially record your authorship. This enables the creator to evidence copyright on a specific date: in some countries this may be necessary to enforce your rights or might provide you with certain other advantages. But generally speaking, you do not have to register your work to become a copyright holder.

- Copyright protection lasts a long time. You will find out more about this later, but for now it’s enough to know that copyright lasts a long time – often many decades after the creator dies.

Note that the combination of points 3 and 4 of this list – automatic entry into the copyright system and very long terms of copyright – has created a massive amount of so-called ‘orphan works’. These are copyrighted works for which the copyright holder is unknown or impossible to locate.

Reflection

Does your university or organisation have a strategy for collectively managing the resources created by everyone who works or studies there? Does your university have a policy regarding ownership of the resources you create while you are at work? Do you think it’s important to have a policy or strategy to support resource use and creation?

A simple history of copyright

Arguably, the world’s most important early copyright law was enacted in 1710 in England – the Statute of Anne:

An act for the encouragement of learning, by vesting the copies of printed books in the authors or purchasers of such copies, during the times therein mentioned.

This law gave book publishers 14 years of legal protection from others copying of their books.

Since then, the scope of the exclusive rights granted under copyright has expanded. Today, copyright law extends far beyond books to cover nearly anything with even a fragment of creativity or originality created by humans.

Additionally, the duration of the exclusive rights has also expanded. Today, in many parts of the world, the term of copyright granted to an individual creator is the life of the creator plus an additional 50 years.

Copyright treaties have also been signed by many countries, meaning that copyright laws have been harmonised to some degree worldwide. You will learn more about the most important treaties and how copyright works around the world in Section 1.3.

The purpose of copyright

There are two primary rationales for copyright law (although rationales do vary among legal traditions):

- Utilitarian: Copyright is designed to provide an incentive to creators. The aim is to encourage the creation of new works.

- Author’s rights: Copyright is primarily intended to ensure attribution for authors and preserve the integrity of creative works. The aim is to recognise and protect the deep connection that authors have with their creative works. (Learn more about author’s rights in the additional resources section.)

While different legal systems identify more strongly with one or the other of these rationales, or have other rationales particular to their legal traditions, many copyright systems (including Myanmar’s) are influenced by and draw from both.

Reflection

Do one or both of these rationales for copyright law resonate with you? What other reasons do you believe support or don’t support granting exclusive rights to creators of original works?

Drawing on the author’s rights tradition, most countries have moral rights that protect, sometimes indefinitely, the bond between an author and their creative output. Moral rights are distinct from the rights granted to copyright holders to restrict others from economically exploiting their works, but they are closely connected.

The two most common types of moral rights are:

- the right to be recognised as the author of the work, traditionally known as the ‘right of paternity’

- the right to protect the work’s integrity, which generally means the right to object to distortion of the work, or the introduction of undesired changes.

Myanmar’s new Copyright Act includes moral rights for creators. Not all countries have moral rights, but in some parts of the world they are considered so integral that they cannot be licensed away or waived by creators, and they last indefinitely. We will find out more about moral rights in Section 1.2.

How copyright works

Copyright applies to works of original authorship, which means works that are unique and not a copy of someone else’s work. Most of the time this requires fixation in a tangible medium, meaning that the work needs to be written down, recorded, saved to your computer, etc.

Copyright law establishes the basic terms of use that apply automatically to these original works. These terms give the creator or owner of the copyright certain exclusive rights, while also recognising that users have certain rights to use these works without the need for a licence or permission.

What’s copyrightable?

In countries that have signed up to the major copyright treaties described in more detail in Section 1.2, copyright exists in the following general categories of works, although sometimes special rules apply on a country-by-country basis. A specific country’s copyright laws almost always specify types of works within each category. Can you think of a type of work within each category?

- literary and artistic works

- translations, adaptations, arrangements of music and alterations of literary and artistic works

- collections of literary and artistic works.

Additionally, depending on the country, original works of authorship may also include, among others:

- applied art and industrial designs and models

- computer software.

As we will see, Myanmar’s 2019 Copyright Act covers all these categories of works.

What are the exclusive rights granted?

Creators who have copyright get exclusive rights to control certain uses of their works by others, such as allowing others to:

- create authorised translations of their works

- make copies of their works

- publicly perform and communicate their works to the public, including via broadcast

- create adaptations and arrangements of their works.

(Note that other rights may exist, according to the country’s laws.)

This means that if you own the copyright to a book, no one else can copy or adapt that book without your permission (with important caveats, which we will discuss in Section 1.4).

Keep in mind that there is an important difference between being the copyright holder of a novel and controlling how a particular authorised copy of the novel is used. While the copyright owner owns the exclusive rights to make copies of the novel, the person who owns a physical copy of the novel, for example, can generally do what they want with it, such as loan it to a friend or sell it to a used bookstore.

One of the exclusive rights of copyright is the right to adapt a work. An adaptation (or a derivative work, as it is sometimes called) is a new work based on a pre-existing work. The new Myanmar Copyright Act protects adapted work but does not include a definition of this term. However Sections 13 and 18(b) of the Act indicate that work that changes from one format to another (from written form to an audiovisual format, for example) will be protected. This means that a work that is created from a pre-existing work can only be created with permission of the copyright holder. It is important to note that not all changes to an existing work require permission. Generally, a modification rises to the level of an adaptation, or derivative, when the modified work is based on the prior work and manifests sufficient new creativity to be copyrightable, such as a translation of a novel from one language to another, or the creation of a screenplay based on a novel.

Copyright owners often grant permission to others to adapt their work: translated novels or screenplays adapted from novels are common examples of this. Adaptations are entitled to their own copyright, but that protection only applies to the new elements that are particular to the adaptation. For example, if the author of a poem gives someone permission to make an adaptation, the person may rearrange stanzas, add new stanzas and change some of the wording, among other things. Generally, the original author retains all copyright in the elements of the poem that remain in the adaptation, and the person adapting the poem has a copyright in their new contributions. Creating a derivative work does not eliminate the copyright held by the creator of the pre-existing work.

Although the term ‘derivative work’ includes but is not limited to the way in which ‘adaptations’ are described in the Berne Convention in some countries, for the purposes of this course and understanding Creative Commons we will use these terms interchangeably.

Does the public have any right to use copyrighted works that do not violate the exclusive rights of creators?

All countries that have signed up to major international treaties grant the public some rights to use copyrighted works, without permission, without violating the exclusive rights given creators. These are generally called ‘exceptions and limitations’ to copyright.

Many countries itemise specific exceptions and limitations, while others use flexible concepts such as ‘fair use’ and ‘fair dealing’. We’ll return to look at what exceptions are included in Myanmar’s new Copyright Act in Section 1.4.

What is important to know is that copyright law does not require the permission of the creator for every use of a copyrighted work. Some uses are permitted as a matter of copyright policy that balances the sometimes competing interests of the copyright owner and the public.

What else should I know about copyright?

As noted at the beginning of this unit, copyright is complex and varies around the world. This unit serves as a general introduction to its central concepts. There are a number of additional concepts that it might be useful to have an awareness of (such as liability and remedies, licensing, and transfer and termination of copyright transfers and licences) and you can find out more about these in the additional resources section.

Further, there are additional considerations for some creative works that copyright law may not address. Cultural and historical contexts and contingencies can influence people’s decisions to use creative works. Traditional Knowledge labels offer identifiers for creative works, recognising their cultural heritage and significance to the communities from where the works originated.

Final remarks

Digital technology has made it easier than ever to copy and reuse work that others have created, and it has made it easier than ever to create and share your own work. In short, copyright is everywhere.

Because nearly every use of a work online involves making a copy, copyright law plays a role in nearly everything we do online. Let’s take a closer look now at the development of Myanmar’s copyright law.

1.2 Myanmar copyright law

A new Copyright Act is on its way!

Learning outcomes

- understand the key points of the new 2019 Copyright Act

- understand the difference between Myanmar’s 1914 and 2019 Copyright Acts.

A history of copyright in Myanmar

The Copyright Act of 1914 was enacted during colonial rule and was retained on independence under The Union of Burma (Adaptation of Laws) Order of 1948. The 1914 Copyright Act only protects work first published in Myanmar or created by Myanmar residents or citizens. Work is protected under the 1914 Act for the creator’s life plus 30 years after their death.

Because this Act was passed more than 100 years ago, it does not reflect many of the new ways in which we create and share material, such as digital content. Neither does it reflect the needs of emerging markets such as the Myanmar film and song industries. Moreover, the 1914 Act is rarely enforced. Because the law is outdated, awareness of copyright in Myanmar is generally low and current practice does not reflect the need to reference resources or seek permission before using material created by others.

To align Myanmar with international standards, a new Copyright Act has been in development for a number of years, with a draft made available in 2015. Between 1914 and 2019, Myanmar signed up to a number of international treaties related to intellectual property and copyright law. (We will review these in Section 1.3.)

‘Intellectual property’ is the term used for rights – established by law – that empower creators to restrict others from using their creative works. Copyright is one type of intellectual property, but there are many others, including trademark law and patent law. The Myanmar Intellectual Property Proprietor’s Association (MIPPA) created a video that celebrates Intellectual Property Day (26 April) and explains the different types of intellectual property, including copyright. You can also find out more about different types of intellectual property in the additional resources section.

Myanmar’s new copyright law was adopted by the Assembly of the Union (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) on 24 May 2019. Early in 2020 the Central Committee for Intellectual Property (CCIPR) was established by the Myanmar government. CCIPR will oversee the setting up of the Myanmar Intellectual Property Rights Agency (MIPRA). The new Copyright Act is anticipated to become law in October 2021, when the Copyright Act of 1914 will then be repealed.

The 2019 Copyright Act

Myanmar’s new 2019 Copyright Act protects all original literary and artistic works from being transmitted, distributed, adapted or reproduced without prior permission from the copyright owner. The Act applies to all works regardless of their mode or format of expression, their content, quality and purpose. The new Act therefore covers both physical and digital formats. It also covers work created by hand (such as paintings or sculptures), or manufactured work. As we saw, earlier work is automatically covered by copyright when the creator starts to put something into a tangible form: for example, if it is written, painted or drawn. Consequently there is no requirement for registering copyright.

The 2019 Act also introduces new terms of copyright protection. In general, copyright protection is the lifetime of the creator plus 50 years after their death. However, audiovisual or cinematographic work will be protected for 50 years from the year it was first made publicly available. Applied arts will be protected for 25 years from the date at which an object was first made.

Work created by both citizens and residents in Myanmar will be covered by the new Copyright Act. However, in the case of broadcasting, audiovisual and cinematographic works, creators should be Myanmar residents or have their office or business in Myanmar. Architecture is only protected under the new law if the respective building is located in Myanmar. Regardless of citizenship or residency, creators are protected by the new Act if their work is performed or first published in Myanmar.

As we will see in Section 1.3, Myanmar citizens’ creations will be covered by copyright in other countries, if Myanmar is a signatory to a number of international treaties.

As noted earlier, the Act also covers ‘adaptations’ – that is, changing a work from one format to another – although there is no definition of this term within the Act. This requires further clarification in the forthcoming Copyright Rules, which were being drafted at the time of writing (September 2020).

There is also an opportunity for the new Copyright Act to clarify whether websites that respond to copyright owners’ requests to remove material posted by others have violated copyright, such as Facebook posts that contain copyrighted content. Outdated copyright law means that currently there is a ‘safe haven’ for websites with regard to copyright notices and takedowns, so websites are not liable for copyright infringement by users. You can find out more about what measures are being taken elsewhere in the world to address this in the additional resources section.

The new Copyright Act will also introduce severe penalties for anyone who violates the law. The minimum penalty will be imprisonment for a term of no more than three years or a minimum fine of 1 million kyat (approximately US$1000), or both. For repeat offenders, sentences will range from three to ten years’ imprisonment plus a fine of no more than 10 million kyat (approximately US$10,000). However, there are some circumstances where copyrighted material can be used without requiring permission from the copyright holder. (These specific circumstances are discussed in Section 1.4).

Section 90 of the new Copyright Act includes provision for a two-year transition period in which the production of unauthorised copies of protected work is still permissible. However, after this period has passed, you will no longer be able to make copies, change or share material without the copyright holder’s permission. So it’s important to start thinking now about what changes you might need to make to your own practice and that of your university or college to ensure that you are ready to comply with the new Act. We will discuss in more detail the implications for Higher Education in section 1.4.

You can read Myanmar’s 2019 Copyright Act (available in Myanmar language), and a number of English-language summaries are provided in the additional resources section.

You may also want to explore the website of the Myanmar Intellectual Property Department, and the Facebook page of IP Myanmar, which regularly posts on intellectual property matters.

Frontier magazine also examines Myanmar’s copyright law and its possible implications, and you can also read EIFL’s assessment of the new law.

Exclusive rights in the new Copyright Act

There are two other categories of rights, called exclusive rights, that are included in the new Myanmar Copyright Act. These exclusive rights are important to understand because, as we’ll see in Section 3.2, the rights are licensed and referenced by Creative Commons licences and public domain tools.

- Moral rights: As mentioned above, moral rights are an integral feature of many countries’ copyright laws. Under the new Myanmar Copyright Act, moral rights last for the lifetime of a creator plus an unlimited period after their death. However, moral rights can be waived under certain conditions. Although Myanmar has not currently signed the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (the ‘Berne Convention’), these rights are recognised in Article 6b. (We will look at the Berne Convention in more depth in Section 1.3.)

- Similar and related rights (including rights known in many countries as ‘neighboring rights’): Closely related to copyright are similar and related rights. These relate to copyrighted works and grant additional exclusive rights beyond the basic rights granted to authors described above. Some of these rights are governed by international treaties, but they also vary country by country. Generally, they are designed to give some ‘copyright-like’ rights to those who are not themselves the author, but are involved in communicating the work to the public: broadcasters and performers, for example. Section 2 of the new Myanmar Copyright Act includes similar and related rights specifically in relation to performers, audiovisual producers and broadcasting organisations. The Act covers not only communication to the public but also importing, uploading on the internet and selling to the public for the purpose of distribution.

As we will see in Unit 2, Creative Commons licences and public domain tools cover these rights, allowing the public to use works in ways that would otherwise violate those rights.

1.3 Global aspects of copyright

Copyright laws vary from country to country, yet we operate in a world where media is global. Over time, there has been an effort to standardise copyright laws around the globe.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- describe how the copyright laws of your country may differ from those of other countries

- identify major international treaties and efforts to harmonise laws around the world.

Reflection

When you publish or reuse something online, have you ever thought about what law applies to you? Does it make sense to you that different people should have different limits to what they can do with your work based on their geographic location? Why, or why not?

Overview

Although copyright laws differ from country to country, the internet has made global distribution and sharing of copyrightable works possible with the click of a button. What does that mean for you when you share your works on the internet and use works published by others outside your country? What law applies to a video taken by someone from India during their travels to Kenya and then posted to YouTube? What about when that video is watched or downloaded by someone in Canada?

Copyright law is locally implemented by every country around the world. In an effort to minimise complexity, efforts have been undertaken to harmonise some of the basic elements of how copyright works across the globe.

Introduction to the global copyright system

International laws

Every country has its own copyright laws, but over the years there has been extensive global harmonisation of these laws through treaties and multilateral and bilateral trade agreements. These establish minimum standards for all participating countries, which then enact or conform their own laws to the agreed-upon limits. This system leaves room for local variation.

These treaties and agreements are negotiated in various fora: the World Intellectual Property Organisation (known as ‘WIPO’), the World Trade Organisation (known as the WTO) and in private negotiations between select countries.

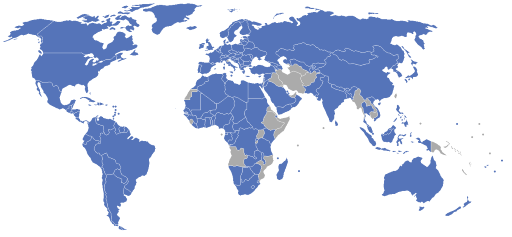

One of the most significant international agreements is the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, concluded in 1886. The Berne Convention has since been revised and amended on several occasions. WIPO serves as administrator of the treaty and its revisions and amendments, and is the depository for official instruments of accession and ratification. As of June 2020, more than 179 countries have signed the Berne Convention. In South East Asia only Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar have not yet signed it. This treaty (as amended and revised) lays out several fundamental principles upon which all participating countries have agreed. One of those principles is that copyright must be granted automatically – that is, there must be no legal formalities required to obtain copyright protection: for example, national laws of its signatories cannot require you to register or pay for your copyright as a condition to receiving copyright protection. In general, the Berne Convention as revised and amended also requires that all countries give foreign works the same protection that they give works created within their borders, assuming the other country is a signatory. The following map shows (in blue) the signatories to the Berne Convention as of 2012.

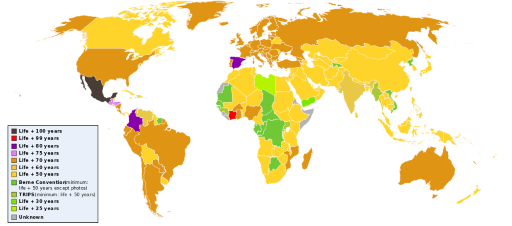

Additionally, the Berne Convention sets minimum standards – default rules – for the duration of copyright protection for creative works, although some exceptions exist depending on the subject matter. The Berne Convention’s standards for copyright protection dictates a minimum term of life of the author plus 50 years. Because the Berne Convention sets minimums only, several countries have established longer terms of copyright for individual creators, such as ‘life of the author plus 70 years’ and ‘life of the author plus 100 years’. The following map shows the status of copyright duration around the world as of 2012.

In addition to the Berne Convention, several other international agreements have further harmonised copyright rules around the world.

Although Myanmar is not currently a signatory to the Berne Convention it has signed up to nine treaties related to intellectual property rights. These include the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation, World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) which all World Trade Organisation (WTO) members abide by. TRIPS requires its members to enact intellectual property laws, including copyright. Myanmar has been granted several extensions to enable the laws to be enacted and the final deadline for implementation is 1 July 2021. For a full list of these intellectual property treaties, see additional resources.

As noted earlier, work by Myanmar citizens does not currently have the same copyright protection elsewhere in the world. For work created by Myanmar citizens to be afforded copyright protection in other countries, Myanmar needs to be a member of the Berne Convention (1886), WIPO Copyright Treaty (1996) and the Marrakesh Treaty (2016) when the new Copyright Act is implemented. The WIPO and Marrakesh treaties cover digital resources and facilitate the sharing of resources for people who are blind or have visual impairments, respectively.

National laws

Although international frameworks exist because of the Berne Convention and other treaties and agreements, copyright law is enacted and enforced through national laws. Those laws are supported by national copyright offices, which in turn support copyright holders, allow for registration and provide interpretative guidance. As mentioned, while there has been a major effort to create minimum standards for copyright across the globe, countries still have a significant amount of discretion as to how they meet the requirements imposed by treaties and agreements. That means the details of copyright law still vary between countries. You can find out more about Myanmar’s Intellectual Property Department and how it can support you on its website.

What law applies to my use of a work restricted by copyright?

A common question of copyright creators and users of their works is which copyright law applies to a particular use of a particular work. Generally, the rule of territoriality applies: national laws are limited in their reach to activities taking place within the country. This also means that generally speaking, the law of the country where a work is used applies to that particular use. If you are distributing a book in a particular country, then the law of the country where you are distributing the book generally applies.

This is true even in the era of the internet, although it is much more difficult to apply. For example, if you are a Canadian citizen travelling to Germany and using a copyrighted work in your PowerPoint presentation, then German copyright law normally applies to your use.

It can be complicated to determine which law applies in any given case. This complexity is one of the benefits of Creative Commons licences, which are designed to be enforceable everywhere. We’ll find out more about Creative Commons in the next unit.

Final remarks

Even though global copyright treaties and agreements exist, there is no single ‘international copyright law’. Different countries have different standards for what is protected by copyright, how long copyright lasts and what it restricts, and what penalties apply when it is infringed.

1.4 Exceptions and limitations to copyright

The limitations and exceptions built into copyright, including ‘fair use’ and ‘fair dealing’ in some parts of the world, were designed to ensure that the rights of the public were not unduly restricted by copyright.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- understand what limitations and exceptions to copyright are, and why they exist

- name a few common exceptions and limitations to copyright

- understand what limitations and exceptions are included in the new Myanmar Copyright Act and what this means for higher education.

Introductions

What would the world look like if copyright did not have any limits to what it prevented you from doing with copyrighted work?

Imagine resorting to Google’s search engine on your laptop or smartphone to settle a disagreement with a friend about some bit of trivia. You type in your search query, and Google comes up empty. You then learn that a court has required Google to delete its entire web index because it never entered into copyright agreements with each individual author of each individual page on the web. By indexing a web page and showing the public a snippet of the contents in their search results, the court has declared that Google violates the copyrights of hundreds of millions of people, and can no longer show those search results.

Fortunately, thanks to exceptions and limitations built into copyright laws in much of the world, this hypothetical situation is unlikely to become reality in many countries. This is one of many illustrations of why it is so important that copyright has built-in limitations and exceptions.

Reflection

Have you ever made a copy of a creative work? If you are studying or researching, how do you usually cite or reference materials? Have you ever asked permission to reproduce material for learning and teaching?

Limitations and exceptions to copyright law

Copyright is not absolute; there are some uses of copyrighted works that do not require permission. These uses are limitations on the exclusive rights normally granted to copyright holders and are known as ‘exceptions and limitations’ to copyright.

When legislators created copyright protections, they realised that allowing copyright to restrict all uses of creative works could be highly problematic. For example, how could scholars or critics write about plays, books, movies or other art without quoting from them? (It would be extremely difficult.) And would copyright holders be inclined to provide licences or other permission to people whose reviews might be negative? (Probably not.)

For this and a range of other reasons, certain uses are explicitly carved out from copyright – including, in most parts of the world, uses for purposes of criticism, parody, access for the visually impaired and more.

Fair use, fair dealing and other exceptions and limitations to copyright are an extremely important part of copyright design. Some countries afford exceptions and limitations to copyright, such as fair dealing, and other countries do not offer exceptions or limitations at all. If your use of another’s copyrighted work is ‘fair’ or falls within another exception or limitation to copyright, then you are not infringing the creator’s copyright. You can find out more about ‘fair use’ around the world and in the context of international treaties, such as the Berne Convention, in the additional resources section. Exceptions and limitations to copyright vary by country. There are global discussions around how to harmonise them. This WIPO study compares the copyright exceptions and limitations for libraries in many countries around the world.

Generally speaking, there are two main ways in which limitations and exceptions are written into copyright law:

- The first is by listing specific activities that are excluded from the reach of copyright. For example, Japanese copyright law has a specific exemption allowing classroom broadcasts of copyrighted material. This approach has the benefit of providing clarity about precisely what uses by the public are allowed and not considered infringing. However, it can also be limiting, because anything not specifically on the list of exceptions may be deemed restricted by copyright.

- The other approach is to include flexible guidelines about what is allowed in the spirit of the three-step test described above. Courts then determine exactly what uses are allowed without the permission of the copyright holder. The downside to flexible guidelines is that they leave more room for uncertainty. You can find out more about ways in which fair use is determined in the United States in the additional resources section.

Most countries also have compulsory licensing schemes, which are another form of limitation on the exclusive rights of copyright holders. These statutory systems make copyrighted content (such as music) available for particular types of reuse without asking permission, but they require payment of specified (and non-negotiable) fees to the copyright owners. Compulsory licensing schemes permit anyone to make certain uses of copyrighted works so long as they pay a fee to the rights holder whose work will be used.

Exceptions in the Myanmar Copyright Act and higher education

Earlier in this unit you read about needing to ask permission from the copyright holder to use of copyrighted material. However, there is a number of exceptions in relation to literary works under the new Myanmar Copyright Act, including:

- reproduction for private use

- quotation

- exploitation for educational purposes

- reproduction and translation in libraries or archives

- exploitation for the press

- ephemeral reproduction for repair or as a backup

- exploitation for disabled people.

The new Copyright Act also excludes any copyright violation that may occur through government activity connected to public policy and security.

As you can see, the new Act allows for works to be reproduced for educational purposes. However, there are certain exceptions to this and a number of rules regarding reproduction of material within this context. One restriction is that you cannot copy a whole book, musical notation or digital database, or a substantial part. This means that you would need permission from the copyright holder to photocopy an entire book, even if you were using it for educational purposes.

In Section 27 of the new Copyright Act, copyright clearance for resources being used for educational purposes and within prescribed amounts is not required. However, you do need to ensure that you reference or include details of the author/creator and the work being reproduced. This applies to:

- a.reproducing any parts of published work or article in newspapers, magazines or journals for the purpose of teaching

- b.incorporating copies of materials mentioned in (a) into digital or printed syllabi for teaching purposes and by education organisations – electronic syllabi should be stored on a secure network that can only be accessed by the relevant students and teachers

- c.a combined use of electronic or printed format literary or artistic works for assignments or research purposes (personal use only), or preservation in the library by persons who will study a specific syllabus.

The new Myanmar Copyright Act does not currently provide a specific definition of the term ‘fair use’ or ‘fair dealing’. This means that clear guidance on what percentage of a book or how many pages can be copied without infringing copyright is needed to ensure that use for educational purposes does not accidentally infringe copyright.

In education, the cost of books and resources is of concern to teachers and students alike. As we saw earlier in this unit, current practice may not always have considered copyright. Whereas previously we might have photocopied resources many times and distributed them, we now need to ensure that we are not breaching copyright when we duplicate material. We also need to ensure that we are referencing the materials we use.

Reflection

What does the new Myanmar Copyright Act mean for your practice? Do you reference the resources you use for teaching and learning? Do you know who owns the copyright of the resources that you use? If you wanted to reproduce large sections of a book and your usage exceeded ‘fair use’ for educational purposes, how would you seek permission to copy the material?

More generally, how might the new Copyright Act impact on our universities? How can we ensure that libraries have enough books and other resources? Is there someone you can ask for advice and assistance at your university or college? How could you support colleagues and students in deepening their understanding of copyright and referencing?

Final remarks

Exceptions and limitations to copyright are just as important as the exclusive rights copyright grants. Think of them as a safety valve for the public in order to be able to utilise copyrighted works for particular uses in the public interest. It is particularly important to be aware of the exceptions and limitations that apply where you live, and what the new Myanmar Copyright Act means for you, so that you can take advantage of and advocate for these critical user rights. In Unit 2 we will look at works that are not subject to copyright (public domain) and introduce Creative Commons.