Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Saturday, 22 November 2025, 2:55 AM

Unit 2: Introducing the public domain and Creative Commons

Introduction

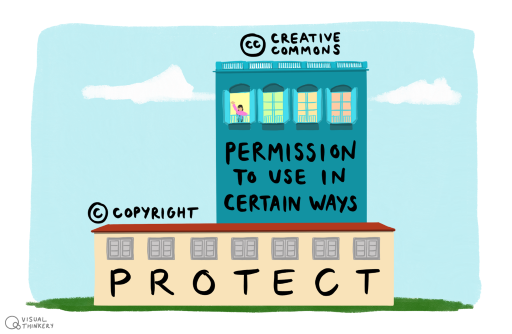

Creative Commons licences do not replace copyright; they are built on top of it.

In Unit 1 we explored copyright and the recent changes to Myanmar copyright law. We started to reflect on how these changes may impact our practice and what we need to consider when using material created by others.

In Unit 2 we are going to introduce public domain resources and find out a bit more about Creative Commons. Public domain resources are not subject to copyright, meaning that they can be shared, changed and used without seeking permission. Creative Commons is:

- a set of legal tools

- a non-profit organisation

- a global network and a movement.

As you might have guessed, Creative Commons has something to do with copyright! It is inspired by people’s willingness to share their creativity and knowledge. This willingness to share is enabled by a set of open copyright licences. Unit 3 will introduce us to a set of tools from Creative Commons to help us identify, share, change and use material created by others without violating copyright. We will explore how we can use these tools and how they could be useful to you later on in the course.

This unit has three sections:

- 2.1 The public domain

- 2.2 The story of Creative Commons

- 2.3 Creative Commons today

There are also additional resources if you are interested in learning more about any of the topics covered in this unit.

2.1 The public domain

The public domain consists of creative works that are not subject to copyright. This is the pool of publicly available material from which new creativity and knowledge may be built.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- understand what the public domain is

- appreciate the value of the public domain.

Reflection

Have you ever looked at ancient temple paintings? Have you listened to a Beethoven symphony? These works are in the public domain. What other public domain works have you enjoyed in your lifetime? Have you ever created something new using a work in the public domain?

Overview

Why is it important that works eventually fall out of copyright? Are there any works that do not qualify for copyright protection and may be freely used?

A critical aspect of copyright law is that the protection it provides does not last forever. After a set term, the copyright expires and the work enters the public domain for everyone to copy, adapt and share. Likewise, there are certain types of works that fall outside the scope of copyright. Note that moral rights may continue to exist in works that have otherwise entered the public domain. As we saw in the last unit, this is the case under Myanmar’s new Copyright Act.

How does something enter the public domain?

Despite the expansive reach of copyright, there is still a rich (and growing) public domain full of works that are free from copyright. Works enter the public domain in one of four ways, as discussed below.

The copyright expires

While copyright terms are longer than ever before, they are not infinite. In most countries, the term of an individual’s copyright expires 50 years after their death. In some countries, the term is longer and can be up to 100 years after the author dies. If you want to be reminded of copyright terms around the world, you can review the map in Section 1.3.

The work was never entitled to copyright protection

Copyright covers vast amounts of content created by authors, but certain categories of works fall outside the scope of copyright. For example, works that are purely functional are not copyrightable, like the design of a screw. The Berne Convention identifies additional categories, such as official texts of a legislative, administrative and legal nature.

Further, in some countries, works created by government employees are excluded from copyright protection and are not eligible for copyright. Section 16 of the new Myanmar Copyright Act notes a number of exclusions from copyright protection, including purely functional works, court orders and government regulation, orders and directives, and laws. As we saw in Unit 1, facts and ideas are never copyrightable.

The creator dedicates the work to the public domain before copyright has expired

In most parts of the world, a creator can decide to forego the protections of copyright and dedicate their work to the public domain. Creative Commons has a legal tool called CC0 (‘CC Zero’) Public Domain Dedication that helps authors put their works into the worldwide public domain to the greatest extent possible. You’ll learn more about this tool (and other Creative Commons legal tools) in Unit 3.

The copyright holder failed to comply with formalities to acquire or maintain their copyright

In most countries there are no formal requirements to acquire or renew copyright protection over a work. This was not always the case, however, and many works have entered the public domain over the years because a creator failed to adhere to formalities.

What can you do with a work that is in the public domain?

You can do almost anything, but it depends on the scope and duration of copyright protection in the country where the work is used. Depending on the country, for example, a work in the public domain may still be covered by moral rights that last beyond the duration of copyright. It’s also possible that a work is in the public domain in one country, but is still under copyright in another country. This means you may not be able to use the work freely where copyright still applies.

A work that is in the public domain for purposes of copyright law may still be subject to other intellectual property restrictions. For example, a public domain story may have a trademarked brand on the cover associated with the publisher of the book. Trademark protection is independent of copyright protection, and may still exist even though the work is in the public domain as a matter of copyright. Also, once a creator uses a public domain work to turn it into a new work, the creator will have copyright on the portions of their new work that are original to them. As an example, the creator of a film adaptation based on a public domain novel will have copyright protection over the film, but not the underlying public domain novel. You can find out more about trademark protection in the additional resources section in Unit 1.

Author credit and the public domain

Even though it may not be legally required in every country, especially those countries where moral rights do not exist after the term of copyright expires, there are many benefits to identifying and giving credit to the original creator, even after their work has entered the public domain. Many communities have adopted norms, which are accepted standards for crediting the authors and the treatment of works in the public domain. Creative Commons has created public domain guidelines that can be used by communities to create their own norms. Review the CC guidelines here.

Reflection

Can you think of a reason why it might be helpful to give credit to an author whose work is in the public domain? Can you think of why norms should be encouraged when public domain works are reused?

Finding works in the public domain

With millions of creative works whose copyright has expired – and many more added regularly with tools like the CC0 Public Domain Dedication – the public domain is a vast treasure trove of content.

Some sites that host works in the public domain are:

- Project Gutenberg

- Public Domain Review

- Digital Public Library of America

- Wikimedia Commons

- Internet Archive

- Library of Congress

- Flickr

- Rijksmuseum.

The CC Search tool is another way to find public domain material. We will take a look at how to use some of these websites and find public domain and other resources that can be used without violating copyright later on in the course.

It is not always easy to identify whether a work is in the public domain. As we learned, copyright protection is automatic, so the absence of a copyright symbol ‘©’ does not mean that a work is in the public domain.

In addition to its CC0 Public Domain Dedication for creators, Creative Commons also has a tool called the Public Domain Mark, designed to label works whose copyright has expired everywhere in the world, so that reusers can easily identify that those works are in the worldwide public domain. As of 2016, CC’s public domain tools were used on more than 90 million works.

Final remarks

A healthy public domain is crucial to preserving our cultural heritage, inspiring new generations of creators, and increasing human knowledge. Because the scope and duration of copyright has grown so much over the years, it can be easy to forget the public domain exists at all. But the public domain is a critical part of the bargain of copyright, and works in the public domain are incredible resources that belong to all of us.

2.2 The story of Creative Commons

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- understand why Creative Commons was founded

- identify the role of copyright law in the creation of Creative Commons.

Reflection

Were you aware of Creative Commons before participating in this course? As you work through this unit, think about how you would explain what Creative Commons is to your colleagues.

Overview

The story of Creative Commons (CC) begins with copyright. CC licences are built on copyright and are designed to give more options to creators who want to share. Over time, the role and value of Creative Commons has expanded.

CC’s founders recognised the mismatch between what technology enables and what copyright restricts, and they provided an alternative approach for creators who want to share their work. Today that approach is used by millions of creators around the globe. To understand how a set of copyright licences could inspire a global movement, you need to know a bit about the history of Creative Commons. This unit focuses on this important background information.

The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA)

The story begins with a particular piece of copyright legislation in the United States: the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA), enacted in 1998. It extended the term of copyright for every work in the United States (even those already published) for an additional 20 years: the life of the creator plus 70 years. (This move put the US copyright term in line with some other countries, although many more – including Myanmar under the new Copyright Act – remain as 50 years after the creator’s death.)

Stanford law professor Lawrence Lessig believed that this new law was unconstitutional. The term of copyright had been continually extended over the years. The end of a copyright term is important: it marks the moment when a work moves into the public domain, whereupon everyone can use that work for any purpose without permission. This is a critical part of the equation in the copyright system. All creativity and knowledge build on what came before, and the end of a copyright term ensures that copyrighted works eventually move into the public domain and thus join the pool of knowledge and creativity from which we can all freely draw to create new works.

The new law was also hard to align with the purpose of copyright as it is written into the US Constitution, to create an incentive for authors to share their works by granting them a limited monopoly over them. How could the law possibly further incentivise the creation of works that already existed?

Lessig represented a web publisher, Eric Eldred, who had made a career of making works available as they passed into the public domain. Together, they challenged the constitutionality of the Act. The case, known as Eldred v. Ashcroft, went all the way to the US Supreme Court. Eldred lost.

Enter Creative Commons

Inspired by the value of Eldred’s goal to make more creative works freely available on the internet, and responding to a growing community of bloggers who were creating, remixing and sharing content, Lessig and others came up with an idea. They created a non-profit organisation called Creative Commons and, in 2002, published the Creative Commons licences – a set of free, public licences that would allow creators to keep their copyrights while sharing their works on more flexible terms than the default ‘all rights reserved’.

As we saw in Unit 1, copyright is automatic, whether you want it or not. And while some people want to reserve all of their rights, many want to share their work with the public more freely. The idea behind CC licensing was to create an easy way for creators who wanted to share their works in ways that were consistent with copyright law.

From the start, Creative Commons licences were intended to be used by creators all over the world. The CC founders were initially motivated by a piece of US copyright legislation, but similarly restrictive copyright laws all over the world restricted how our shared culture and collective knowledge could be used, even while digital technologies and the internet have opened new ways for people to participate in culture and knowledge production.

Since Creative Commons was founded, much has changed in the way people share and how the internet operates. In many places around the world, the restrictions on using creative works have increased. Yet sharing and making changes to resources – that is, ‘remixing’ – are the norm online. Think about music tracks that comprise different pieces of existing music (sometimes called a mash-up), or even the photos your friend posted on Facebook last week. Sometimes this type of sharing and remixing happen in violation of copyright law. Sometimes they happen within social media networks that do not allow those works to be shared on other parts of the web.

Reflection

How often do you ask copyright owners for permission to share their material with colleagues and friends? Do you check whether you can reuse materials created by others?

In domains like textbook publishing, academic research, documentary film, and many more, restrictive copyright rules continue to inhibit creation, access and remix. CC tools are helping to solve this problem. In December 2019, Creative Commons licences were reported to have been used by more than 1.6 billion works online across 9 million websites. The grand experiment that started more than 15 years ago has been a success, including in ways unimagined by CC’s founders.

While other custom open copyright licences have been developed in the past, we recommend using Creative Commons licences because they are up to date, free-to-use, and have been broadly adopted by governments, institutions and individuals as the global standard for open copyright licences. They are also machine-readable, which means that material with a Creative Commons licence can be easily understood by applications, search engines and other kinds of technology. We will find out more about the different aspects of CC licensing in Section 3.1.

In the next section, you’ll learn more about what Creative Commons looks like today: the licences, the organisation and the movement.

Final remarks

Technology makes it possible for online content to be consumed by millions of people at once, and it can be copied, shared and remixed with speed and ease. There are many barriers to using material online, for example accessibility of resources. Copyright law places limits on our ability to take advantage of these possibilities. Creative Commons was founded to help us realise the full potential of the internet.

2.3 Creative Commons today

As a set of legal tools, a non-profit, as well as a global network and movement, Creative Commons has evolved in many ways over the course of its history.

Learning outcomes

By the end of this section of the course, you will be able to:

- differentiate between Creative Commons as a set of licences, a movement and a non-profit organisation

- explain the role of the CC Global Network

- describe the basic areas of work for CC as a non-profit organisation.

Reflection

Are you already involved with Creative Commons as a creator, reuser and/or advocate? Would you like to be?

Introduction

Now we know why Creative Commons was started. But what is Creative Commons today?

Today, CC licences are prevalent across the web and are used by creators around the world for every type of content you can imagine. The open movement, which extends beyond just CC licences, is a global force of people committed to the idea that the world is better when we share and work together. Creative Commons is the non-profit organisation that stewards its licences and helps support the open movement.

Today, the CC licences and public domain tools are used on more than 1.6 billion works, from songs to YouTube videos to scientific research. The licences have helped a global movement come together around openness, collaboration and shared human creativity. Once housed within the basement of Stanford Law School, Creative Commons now has a staff working around the world on a host of different projects in various domains.

We’ll take these aspects of Creative Commons – the licences, the movement and the organisation – and look at each in turn.

Creative Commons licences

CC legal tools are an alternative for creators who choose to share their works with the public under more permissive terms than the default ‘all rights reserved’ approach under copyright. The legal tools are integrated into user-generated content platforms like YouTube, Flickr and Jamendo, and they are used by non-profit open projects like Wikipedia and OpenStax. They are used by formal institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the British Library, and individual creators. We will find out more about the different CC licences and how to look for different types of CC-licensed resources in Units 3 and 4.

In addition to giving creators more choices for how to share their work, CC legal tools serve important policy goals in fields like scholarly publishing and education. Watch the video ‘Why open education matters’ to get a sense for the opportunities that Creative Commons licences create for education. Collectively, the legal tools help create a global commons of diverse types of content, from picture storybooks to comics, that is freely available for anyone to use.

CC licences may additionally serve a non-copyright function. In communities of shared practices, the licences act to signal a set of values and a different way of operating.

For some users, this means looking back to the economic model of the commons. As economist David Bollier describes it, ‘a commons arises whenever a given community decides it wishes to manage a resource in a collective manner, with special regard for equitable access, use and sustainability.’ Wikipedia is a good example of a commons-based community around CC-licensed content. You can find out more about the commons in the additional resources section.

For others, the CC legal tools and their buttons express an affinity for a set of core values. CC buttons have become ubiquitous symbols for sharing, openness, and human collaboration. The CC logo and icons are now part of the permanent design collection at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City.

While there is no single motivation for using CC licences, there is a basic sense that CC licensing is rooted in a fundamental belief that knowledge and creativity are building blocks of our culture rather than simple commodities from which to extract market value. The licences reflect a belief that everyone has something to contribute, and that no one can own our shared culture. Fundamentally, they reflect a belief in the promise of sharing.

The Creative Commons movement

Since 2001, a global coalition of people has formed around Creative Commons and open licensing. This includes activists working on copyright reform around the globe, policymakers advancing policies mandating open access to publicly funded educational resources, research and data, and creators who share a core set of values.

There are lots of ways to get involved in Creative Commons. CC has a formal CC Global Network, which includes lawyers, activists, scholars, artists, and more, all working on a wide range of projects and issues connected to sharing and collaboration. The CC Global Network has more than 500 members, and 40-plus Chapters around the world. Indonesia, Taiwan, Japan, India, Bangladesh and Nepal all have CC Chapters. As at August 2020 there was no Myanmar Chapter of Creative Commons.

The CC Global Network is just one player in the larger open movement, which includes Wikipedians, Mozillians, open access advocates, and many more.

Open source software is cited as the first domain where networked open sharing produced a tangible benefit as a movement that went much further than technology. The Conversation’s explainer of other movements adds other examples, such as open innovation in the corporate world, open data (see the Open Data Commons) and crowdsourcing. There is also the open access movement, which aims to make research widely available, the open science movement, and the growing movement around open educational resources.

Creative Commons the organisation

A small non-profit organisation stewards the Creative Commons legal tools and helps power the open movement. CC is a distributed organisation, with CC staff and contractors working around the world, and can be contacted via its website.

Creative Commons:

- works on technical infrastructure designed to make it easier to find and use content in the digital commons

- thinks about ways to better adapt all of CC’s legal and technical tools for today’s web.

Final remarks

Creative Commons has grown from a law school basement into a global organisation with a wide reach and a well-known name associated with a core set of shared values. It is, at the same time, a set of licences, a movement and a non-profit organisation.

Now that we’ve introduced Creative Commons and the public domain, let’s take a deeper look at the different types of licences that enable us to share, adapt and use resources without violating copyright.